Life

| 1922- [Máire or Maire Mac Entee; bapt. Máire Caitríona Mhac an tSaoi (after her grandmothers)]; b. 4 April 1922, in Dublin, dg. of Seán MacEntee and Mairead [née Margaret Browne/de Brún - a niece of Monsignor Padraig de Brún]; ed. Alexandra College, Dun Chaoin [Dunquin], and Beaufort (Rathfarnham); grad. BA, UCD (Celtic Studies & Mod. Langs.); completed MA Diss. on Piaras Feirtéar [Pierce Ferriter], 1945; studies at Institut des Hautes Études, Sorbonne Paris [Institut des Hautes Études] after the war - a deferred studentship; contrib. first to Comhar, ed. by Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh and Tomás de Bhaldraithe; entered King’s Inns; Irish Bar, 1944 - one of two women to be called; published Two Arthurian Romances (1946); entered Irish Dept. of Foreign Affairs, 1947, holding third secretary posts in Paris, Rome and Madrid - where she was officially presented to Franco at the Palacio del Oriente - and Dublin; published critical views Seán Ó Ríordáin’s Eireaball Spideoige (1952) for its departure from traditional idiom, upsetting the poet upset deeply; |

| seconded to Dept. of Education; appt. founding Sec. of Irish Cultural Relations Committee, 1951-52; and at DIAS worked on the English-Irish Dictionary (ed. de Bhaildraithe), 1952-56; had unhappy affair with an Irish Protestant divorcée [var. married Irish scholar] with whom she had previously fallen in love as a girl at Dunquin, aetat 20; appt. to the International Desk of Foreign Affairs, 1956-61; expressed unabashed ideas about female sexuality in "Ceathrúintí Mháire Ní Ógáin" in Margadh na Saoire (1956); joined Irish Delegation to UN Gen. Assembly, 1957-60; became permanent representative of Ireland to Council of Europe, Strasbourg, 1961; resigned from the European Council and DFA and moved to Ghana and afterwards New York with Conor Cruise O’Brien, m. 1962 (following his Mexican divorce from Christine Foster); adopted with him two African children, Patrick and Margaret; taught the background of Anglo-Irish literature at Queen’s College [NY], along with Liam and Máire de Paor; arrested with Ginsberg and others at anti-Vietnam War demonstration in NY, 1967; winner of the O’Shaughnessy Poetry Award of the Irish American Cultural Institute, 1988; |

| visiting lect. in Folklore Dept. of Univ. of Pennsylvania, 1989; also taught at Queen’s College, New Yorked. Poetry Ireland Review; appt. Writer in Residence at UCD, 1991; awarded a D.Litt. Celt. honoris causa by the National University of Ireland [NUI], 1992; elected to Aosdana, 1996, she sought the impeachment of Francis Stuart for his wartime anti-semitism and resign in response to the adverse outcome, 26 Nov. 1997; winner of Oireachtas Prize, and read with Yevtushenko in Dingle, 1997; issued autobiography as The Same Age as the State (2003); residing with her husband in ‘Whitewater’, at the summit of Howth Hill; appt. adjunct professor of Irish studies at NUI Galway in 2005; suffered the death of her husband Conor, 19 Dec. 2008; honoured by the Imram festival in 2009; read at the Douglas Hyde Annual Conference, 2009, with Michael D. Higgins, et al.; issued Scéal Ghearóid Iarla, 1335-1398 (2011), winner of irish Language Book of the Year, 2011; honoured and at Listowel Writers Week, 2013; d. 16 Oct., 2021 [aetat. 99]. DIW FDA OCIL |

[ top ]

Works| Poetry |

|

| Selected (bilingual) |

|

| Fiction |

|

| Articles (sel.) |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| Autobiography |

|

| Discography |

|

[ See Wikipedia/Vicpéid page on Mac an tSaoi in Irish - online; see also her page at Cois Lífe - online ]

[ top ]

Criticism| Articles |

|

| See obituary in The Irish Times (17 Oct. 2021) - online; accessed 14.11.2022 |

[ top ]

Commentary

Robert O’Driscoll, ed., The Celtic Consciousness [papers of 1978 symposium at Toronto] (Dublin: Dolmen Press; Edinburgh: Canongate Publ. 1982), Maire Cruise O’Brien [sic], ‘The role of the poet in Gaelic Society’, pp.243-54. [Speaking of ‘my Gaeltacht’ on the Western seaboard]: Those who can adapt to the new, adapt - many with startling success, some with deep traumatic lesions - those who cannot adapt, die - of the want of the will to live. This is literally true; easily two-thirds of my school-mates and near contemporaries in one such district are dead - all in their forties or fifties. [243]; Speaks of Micheal Ó Gaothin, who - ‘his compulsive self-neglect notwithstanding, had the status of a poet; and of a collection offered him by ‘a group of exploiting literati’, entitled Connle Corra (Dublin 1968). [244]; comments that the word for sorcerer in the line ‘Ach cantaireacht na nAltach’ means Ulsterman [Ultach]. [245]; On Eibhlin Ni Chonnail: ‘Poor Nelly, as her family called her - she has been demoted; she is no longer a poet, only a poem.’ [248]; Instances Sean Ó Riordain as ‘the first Gaelic poet of any standing to attempt a break - only partially successful - with this vestigial, insular, in-tradition we are exploring [viz., the anti-feminist superstition], has summed up her dilemma rather splendidly in one of his recently published, alas posthumou, pieces, ‘odd that a woman should be a poet!/Surely it is the stallion’s trade?’ [248]; Quotes extensively from Spenser (‘The third sort is called the Aosdan, which is to say in English, the bards, or riming septs .... rakehelly ... great store of cattle ... to the great impoverishment of the Commonwealth’) attrib. same to our “gentleman subject” and his Elizabethan account, without ref. to Spenser, but with ftn., quoted in Brian O Cuiv, ed., Seven Centuries of Irish Learning, 1000-1700 (Dublin 1961), pp.45-50; Offers conjectures that the ‘fickle Countess’ of satirical verses on Gearoid Iarla was in fact the sovereignty of Ireland, since the real countes was faithful, and his father made unsuccessful bid for the High Kingship. [251]; Characterises Godfraidh Fionn O Dalaigh as ‘an opportunist’s opportunist even among poets [since] he praised Gael and Norman indiscriminately, glorying in it.’ [251];

Irish - that is Gaelic - verse is so intensely conservative that it has taken a major cataclysm to cause it to change.’ [252; lists the crisis as coming of Christianity, the Norman conquest and reform of the Gaelic church, and the final breakdown of the Gaelic order after Limerick.]; ‘Today it is possible that yet another crisis, this time the death-throes of a language, is producing another last flowering.; On Cre na cille: ‘Typically, Irish country people conceive of death at three levels: one orthodox Christian, one rational, and one primeval; in this last the dead are present, resentful and vindictive beneath the actual sod. All three coexist without conflict in the folk mind and this is the stuff of our one entirely mature contemporary piece of prose. We seem to take more naturally to verse! [END; 253.]

Mary O’Malley, ‘Language of the Heart’ [interview-article], in The Irish Times, Weekend (26 Feb. 2000), quotes Mac an tSaoi: ‘I was an extraordinarily fortunate child.’ She has edited a large body of work from classical Irish and is an authority on bardic poetry and is as respected a scholar a she is as a poet. She was a member of the Irish delegation to the UN from 1957-60. She fell in love with Conor Cruise O’Brien and visited him in Katanga in 1962, a private tryst that resulted in a blaze of publicity in the English press, her return to Ireland and both their resignations. / Further quotes: ‘“I shouldn’t have gone to Katanga”, she says with a twinkle. “I’d have sacked myself”. “Bright girls are hard to marry”. She [adds] with amusement.’ Translated Rilke into Irish and held audience at Cúirt spellbound with those translations. Mac an tSaoi, further: ‘We were brought up very markedly not anti-Semitic, even before the war. And we were brought up very markedly and strongly to heal the breach of the Civil War. We believed that that was what we had to do. In a lot of ways we were brought up with a very nice balance between conviction and tolerance.’ “Shoa”, the title poem [Shao agus Dánta Eile (Sáirséal agus Ó Marcaigh)] has been illustrated in The Book of Ireland by a survivor of death camps and signed with his number; she believes it is one of the best she has written. ‘The title means Holocaust in Hebrew and the poem is short and brutal. The last line “Ar a chosa deiridh deiridh don mBrútach” is more powerful in amendment than in the earlier draft which has made it into the new new book, the title of which is missing the f inal “h” of the original word Shoah.’ Cites “Máire ag Caoineadh Mháirtín” (to Ó Direáin); “Meas Madra”, for Cathal Ó Searcaigh; “Deonú Dé, 1998”, a memorial to Kate Cruise O’Brien which also addresses the Omagh massacre; also translations of “Leda and the Swan” and “Cuchulainn Comforted” by Yeats.’ [Cont.]

Further (Mary O’Malley, ‘Language of the Heart’, 2000) cont.: Quotes Mac an tSaoi: ‘[…] I didn’t take my writing seriously. That is one of my big regrets’; ‘My writing was always a hobby. It didn’t require any equipment. Nothing that you could lose.’ ‘I owed it to those who saw to it that I knew the language well I owed it to them to put it to better use. I feel that strongly as an older woman.’ Mac an tSaoi is still writing, ‘but only under pressure of great emotion.’ Quotes: ‘Ceileatram uirthi an Ghaolainn / Ach dá labhróinn as Béarla, / Ni sheasódh an croí [The Irish disguises her, / but if I spoke in English, / Heart could not endure.]’ Of “In memoriam Kate Cruise O’Brien”, written after the sudden death of her stepdaughter almost two years ago: ‘if I said it in English who could bear it?’

Further: ‘It puts a veil over the actual heartbreak, the form, in a way. If I were to say it in English it would be a violation of privacy, among other things.’ When asked if she thinks Irish formally more equipped to deal with personal emotion: ‘I think actually that Irish reflects a society in which emotions were expressed with reserve and dignity. But accurately. I think there’s a different tradition - but also, of course, it removes you one step from the reality of contemporary Ireland. It’s not so much that this [writing in Irish] makes poetry less exploitative, because poetry of its nature is exploitative, but it makes it exploitative at one remove and therefore tolerable for both the poet and the reader.’ [See further on Máirtín Ó Direáin, infra.]: ‘He’s a very underestimated poet even by his admirers […] this idea that he’s only a nostalgic poet. There’s a poem of his that opens: “Trua ar fireann ar an uaigneas / sad to be male in solitude”. And because, I think he belonged to, and was writing for, a puritanical generation of English speakers nobody, but nobody, that I know of, has spoken of the passionate cry that comes through in that. That isn’t any soft nostalgia. “How can we live on this bare stone without women,” is what he’s saying.’

Maurice Harmon, ‘First Internationals’, review of The Same Age as the State, in Books Ireland (April 2004): Harmon remarks on absence of pain and conflict of lower middle-class life in Dublin exemplified by Clarke and Devlin, and adds: ‘She is reticent, not confessional / But for more public matters she is full of excitement, passionately involved, has a relish for life, a love of Irish, a loyalty to family, ot her remote and greatly respected father, her mother who had to work to support the family, her uncle Paddy Burke, the Churchman who rose in the ranks, who built the holiday home in Dunquin where he gathered her family and was in effect a surrogate father [and from whom] she received love, encouragement and commitment to learning and language.’ tensions He quotes: ‘like most people whose talent it is to exploit their emotioins, I prefer to do so under the decent veil of literary convention, and not in any immediate capacity as witness, or advocate.’

Further: ‘The era for which I speak was no mean era, and the people who inhabited it no mean people.’ Of those bent on restoring the Irish language ‘to its rightful dignity as the national language of Ireland […] This was a great, life-enhancing undertaking that permeated and enriched their entire experience and was, without exaggeration, an influential factor in every quotidian decision they were called upon to make’ and speaks of young people throughout the country with this dream as ‘incandescent with fun and hope and self-confidence’. (p.79f.)

See also The Linenhall Review (April 1991), where Harmon writes with particular reference to “Margadh na Saoire”: ‘Before expression of women’s experience became customary, she wrote with passion and honesty about love and loss’. O’Brien is outspoken in her dislike of Daniel Corkery, Roger McHugh and Francis Stuart.

Louis de Paor, ‘A Poetics of Refusal: The Poems of Máire Mhac an tSaoi, 1922-2021&146; - Cambridge Irish Studies Group at Magdalene College, Oxford (15 Nov. 2022): This talk will explore the tension between apparently irreconcilable pressures in the poems of Máire Mhac an tSaoi, with particular emphasis on the disjunction between transgressive content and formal conservatism in her work. The influence of her family background and her alignment with the language, literature and cultural tradition of the west Kerry Gaeltacht will be discussed and its implications for reception of her work considered. Her notoriously critical reviews of the work of her contemporary, Seán Ó Ríordáin, will be read in the context of arguments presented by both poets that the Irish language offered a vehicle for resistance to globalised conformity and cultural homogeneity in the decades following the second world war. The extent to which her achievement may or may not have been compromised by her radical and enduring commitment to a regional dialect she herself understood to be in decline by the closing decade of the twentieth century will also be discussed. (Connection with Zoom; email notice of 14.11.2022.)

[ top ]

Quotations

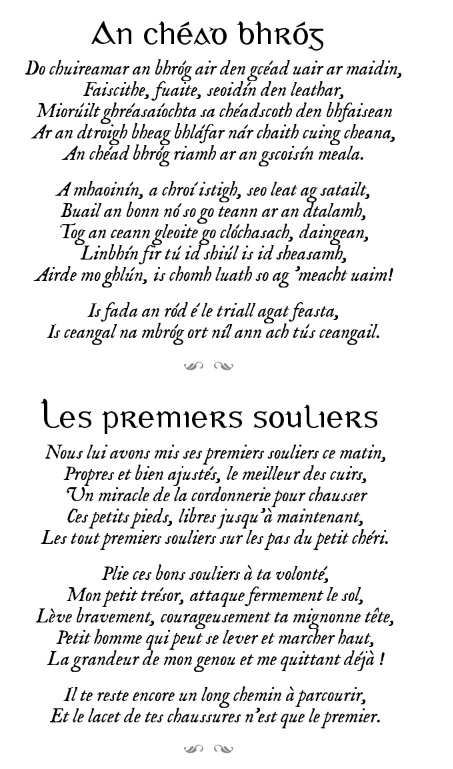

“An chead brhog/The first shoes”: Do chuireamar an bhróg air den gcéad uair ar maidin, / Fáiscithe, fuaite, seoidín den leathar, / Miorúilt ghréasaíochta sa chéadscoth den bhfaisean / Ar an dtroigh bheag bhláfar nár chaith cuing cheana, / Ah chéad bhróg riamh ar an gcoisín meala. // A mhaoinín, a chroí istigh, seo leat ag satailt, / Buail ar bonn nó so go teann ar an dtalamh, / Tóg an ceann gleoite go clóchasach, daingean, / Linbhín fir tú id shiul is id sheasamh, / Airde mo ghlún, is chomh luath so ag 'meacht uaim! // Is fada an ród é le triall agat feasta, / Is ceangal na mbróg ort níl ort ach tús ceangail.’

English Translation by Peter Sirr: “The First Shoes”/ For John David / ‘We put his shoes on for the first time this morning / Neat and snug, the best of leather, / A miracle of shoemaking to adorn / The little feet that ran free till now, / The first shoes ever on the little honey steps. // Bend these fine shoes to your will, / My little treasure, strike the ground firmly, / Lift your darling head bravely, boldly, / Little man who can stand and walk tall, / The height of my knee and already leaving me! // You have a long road to travel yet, / And the spancel of shoes is only the first.’

|

| —From An Paróiste M´orúilteach/the Miraculous Parish, ed. Louis de Paor (Cló Iar-Chonnacht/O’Brien Press 2011), pp.64-65; trans. by Antoine Malette, based on Peter Sirr’s English version on facing-page of that edition. See Antoine Malette web-blog (3 Aug. 2013) - online [accessed 26.02.2017 - following Facebook notification by William Wall and Lillis Ó Laoire (25.02.2017). |

[ top ]

“A fhir dar fhulaingeas”: ‘A fhir dar fhulaingeas grá fé rún, / Feasta fógraím an clabhsúr: / Dóthanach den damhsa táim, / Leor mo bhabhta mar bhantráill. // Tuig gur toil liom éirí as, / Comhraím eadrainn an costas: / ’Fhaid atáim gan codladh oíche / Daorphráinn orchra mh’osnaíle. // Goin mo chroí, gad mo gháire, / Cuimhnigh, a mhic mhínáire, / An phian, an phláigh, a chráigh mé, / Mo dhíol gan ádh gan áille. // Conas a d’agróinnse ort / Claochló gréine ach t’amharc, / Duí gach lae fé scailp dhaoirse - / Malairt bhaoth an bhréagshaoirse! // Cruaidh an cás mo bheith let ais, / Measa arís bheith it éagmais; / Margadh bocht ó thaobh ar bith / Mo chaidreamh ortsa, a óigfhir.’

English translation by Biddy Jenkinson: ‘Man, for whom I suffered love / In secret, I now call a halt. / I’ll no longer dance in step. / Far too long I’ve been enthralled. // Know that I desire surcease, / Reckon up what love has cost / In racking sighs, in blighted nights / When every hope of sleep is lost. // Harrowed heart, strangled laughter; / Though you’re dead to shame, I charge you / With my luckless graceless plight / And pain that plagues me sorely. // Yet, can I blame you that the sun / Darkens when you are in sight? / Until I’m free each day is dark - / False freedom to swap day for night! // Cruel fate, if by your side. / Crueller still, if set apart. / A bad bargain either way / To love you or to love you not.’

(From An paróiste míorúilteach/The miraculous parish: Rogha dánta/Selected Poems), ed. Louis de Paor (Dublin:The O’Brien Press/Cló iar-Chonnacht, 2010, q.pp.; rep. in The Poetry Project: Poetry and Art from Ireland - online; accessed 25.02.2107. See also Aideen Barry, “Beyond the Flock” - an accompanying video - online.)

[ top ]

References

Declan Kiberd & George Fitzmaurice, et. al. eds. An Crann Faoi Bhláth/The Flowering Tree, Contemporary Irish Poetry with Verse Translations (Wolfhound 1991). Also, Katie Donovan, AN Jeffares, and Brendan Kennelly, eds., Ireland’s Women (Dublin: G&M 1994), selects ‘The Hero’s Sleep.

See also Grattan Freyer, ed., Modern Irish Writing (1979), selects poem, ‘No Compromise’.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, gen. ed. (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3, 817 [ed. comm, the scope of her early work is confined, but her common themes of friendship, love and sexual relations are treated in her best poems with a passionate intensity’; her collected poems, An Cion &c, 1987), reveals a wider range of concern and a sustained fluency of style’]; selections from An Cion Go Dtí Seo, ‘Inquistio 1584’ [an elegy for Sean MacEdmund MacUlick, hanged in Limerick]; ‘Finit’ [and trans]; Do Shíle’, ‘For Sheila’ [regarding a marriage contract of an older woman, ‘We doubt you or your like ever existed’, and the tradition, ‘there will tunes I’ll not hear ever ... without your being again there in the corner’]; Gniomhartha Corportha na Trócaire’, ‘The Corporal Works of Mercy’ [an old woman in hospital, nightdress hised up; tinker children; neighbours and nits (incl. allusion to her adopted son Patrick]; Cré na Mna Tí, ‘The Housewife’s Credo’ [duties, and ‘like Scheherazade, you will need to write poetry also’, ‘ach, ar nós Scheicheiriseáide,/Ní mór duit an fhilíocht chomh maith’]; Ceathrúiní Mháire I Ogáin’, ‘Mary Hogan’s Quatrains’ [‘I care little for people’s suspicions/I care little for priests’ prohibitions/For anything save to lie stretched/Between you and the wall’] [904-908]; BIOG 935, b. 1922, m.1962.

Patrick Crotty, ed., Modern Irish Poetry: An Anthology (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1995), selects “Caoineadh” [138], trans. as “Lament ” [139]; “Ceathrúintí Máire Ní Ógáin” [138], trans. as “Mary Hogan’s Quatrains” [139; and see note, infra]. (Translations by Crotty.)

Anne Owen Weekes, ed., Attic Guide to Irish Women Writers (1993) cites Mac an tSaoi, ‘At Work, Poet as Housewife’, with page refs. 22-24, but no source.

[ top ]

Notes

Making a fool ...: “Ceathrúintí Máire Ní Ógáin”: the poem explores an unhappy love affair (viz., with an Irish Protestant in your thirtieth year) and reflects the Munster expression ‘na bi ag deanamh Maire Ni Ogain’ [Don’t be making a Mary O’Hogan of yourself’] - viz., making a fool of yourself. (See Crotty, Modern Irish Poetry, Blackstaff 1995, p.137.)

Hugh Oram, in a review of Sean Lysaght’s life of Robert Lloyd Praeger (1999), notes that Máire Mac an tSaoi visited Praeger to insist that his language in a series on Ireland for Mercier Press subvented by the Cultural Relations Committee should be politically correct, avoiding any reference to ‘British Isles’ or ‘Londonderry’. (Books Ireland, Summer 1999, p.183.)

“Letterlee”, a poem by her, is used as epigraph to Joseph Brady [pseud of Maurice Browne], The Big Sycamore (1958).

All-weather friend: Máire Mac an tSaoi appeared on the Joe Duffy Show (RTE Liveline) to defend Cathal Ó Searcaigh [q.v.], then under attack for purportedly seducing boys in Nepal, saying in his defence - and in the face of his admission in the film made by Neasa Ní Chaináin - that the director of the film has betrayed a friend and that she herself found it ‘difficult to believe the boys were innocent before those encounters’ since ‘little Asian boys are brought up to know about sex.’ (March 2008.)

[ top ]