Life

| 1923-64 [bapt. Francis Aidan, called Brendan; gl., Breandán Ó Beacháin]; b. 9 Feb. Holles St. Hospital, Dublin [though purporting to be born in ‘great lord’s house which had gone to ruin’, Northside central Dublin]; grew up in Crumlin, son Stephen Behan, a highly-literate house-painter, and Kathleen Behan (‘mother of the Behans’), prev. married to Jack Furlong, who died of influenza in 1918, with whom two children; afterwards employed as a maid by Maud Gonne; she also stitched uniforms for the Volunteers in 1916, and was arrested at aetat. 77; four more children, all boys, with Stephen Behan, whose mother was one Christine English [who had remarried]; Stephen fought on the Republican side in the Civil War and was gaoled in Kilmainham, after which he turned his back on politics and espoused family instead (‘Don’t you dare call me a Stater. I fought against the murder gang before yeh were born. I was in jail ... If you’re ever half the Republican I was you’ll be lucky’); his mother was the more politically intransigent of the two; | ||

|

||

| Behan was a nephew of Peadar Kearney [q.v.], author of “Amhrain na bhFiann [The Soldier’s Song]”, and also P. J. (‘Paddy’) Bourke, and hence cousin to Seamus de Burca, who wrote a life (1985); lived at 13 Russell St., adjacent to Croke Park, in the home of matriarchal Granny English who introduced him to whiskey (‘good for the worms’); Behan subsequently said he couldn‘t ‘ever remember not drinking’; ed. by Sisters of Charity NS, and CBS, Brunswick St.; influenced by strong political feeling in his family, incl. those of Mrs. Furlong, his mother’s mother-in-law by her first marriage, who possessed a ‘ferocious revolutionary outlook’; joined the Fianna youth organisation of the IRA [Óglaigh na hÉireann], 1937 [aetat 14], but discharged for disorderly conduct under the influence of drink; contributed patriotic prose and verse to Fianna, The Voice of Ireland, Wolfe Tone Weekly and The United Irishman; | ||

| admitted to Second Battalion of the IRA, 1939, and trained in bomb-making in Killiney [aetat. 16]; travelled to England on mission to bomb Liverpool docks after the IRA declared ‘war’ on Britain, on his own initiative [acc. Ulick O’Connor], and arrested there in possession of a bomb-making kit within ten hours of his arrival, Nov. 1939; professed his ‘proud privilege and honour to stand in an English court to testify to the unyielding determination of the Irish people to regain every inch of our national territory’ in court; held on remand in Walton Prison (Liverpool), where remained for two months and was subjected to brutality on the eve of the execution of Barnes & McCormack [aka Richards] in Birmingham on 7 Feb. 1940 for their supposed part in the Coventry bombings of 25 Aug. 1939 (in which 5 people were killed); tried on 7 Feb., 1940; professed his motives in court: ‘It is my proud privilege and honour to stand in an English court to testify to the unyielding determination of the Irish people to regain every inch of our national territory’; his sentence coincided with the date of execution of Barnes and McCormack for the Coventry bombing; | ||

| committed for three years to the Borstal detention centre at Hollesley Bay, arriving shortly after his seventeenth birthday; encouraged by the governor Mr C. A. Joyce, and in contact with an inspiring priest, one Fr. Behan [sic], and was then deported to Ireland, Nov. 1941 [var. Dec.]; won essay prizes while at Borstal and was treated with special leniency by British authorities, diminishing his original anti-British sentiment (‘I stopped trying to find political solutions and began seriously to write’); greeted in Irish by customs officer on returning to Dublin, while the special branch detectives remained silent; arrested in Dublin for attempting to shoot Detective Kirwan after the annual Easter Commemoration at Glasnevin, 5 April 1942; arrested 10 April and sentenced to fourteen years, 25 April [err. May] of which he served five years, being released at the General IRA Amnesty of 1946 [var. 1943]; on arrival at Mountjoy Prison he was visited by Sean O’Faolain - invited by the governor - who subsequently printed “I Became a Borstal Boy” in The Bell (June 1942); transferred to Arbour Hill, then Curragh after sentencing; learned Irish from native-speaker Republicans and read voraciously; wrote The Landlady, a lost play; | ||

| drafted The Quare Fellow as “Casadh an tSugain Eile” [orig. as “The Twisting of Another Rope”] (in a reference to Douglas Hyde’s Irish-language play Casadh an tSúgain), Curragh 1945, released under general amnesty, Dec. 1946; wrote “Filleadh Mhic Eachaidh”, elegy for hunger-striker Sean McCaughey; visited Irish speaking regions, Blaskets, Dingle, and Connemara; began to frequent the Catacombs (being a basement flat at Fitzwilliam Pl., off Merrion Sq.); wrote Gretna Green (Queen’s Th., Feb. 1947), as part of republican commemoration; served one month sentence for breach of the peace, May 1948; visited Paris, August 1948, initially as a guest of John Beckett, the cousin of Samuel Beckett, with whom he shared a room in the Grand Hôtel des Principautés Unies, 26, rue de Servadoni, 6ième Arr.; worked as a house painter, and lived for a time on the rue des Feuillantines (5ième Arr.); arrested for drunkenness and bailed out by Sam Beckett; purported to have addressed Sartre and Beckett in La Cupole with, ‘I’m a writer, too’; made trips to Dublin and Belfast; endured a further period of imprisonment in Strangeways for his part in the escape of an IRA member; returned to Paris with Anthony Cronin, 1950; his poetry appeared in Seán Ó Tuama, ed., Nuabhéarsaíocht (1950); also wrote radio plays, Moving Out (1952) and A Garden Party (1952), both for Radio Éireann; | ||

|

||

| contributed to Irish Press from Paris, 1954-56, producing pieces later published as Hold Your Hour and Have Another (1963); The Scarperer (1966), a crime story, serialised in The Irish Times in 1953 (publ. posthum. 1966); submitted The Quare Fellow (dealing with prison execution of Bernard Kirwan) to the Abbey, then Sally Travers at the Gate, who rejected it but recommended to Alan Simpson and Carolyn Swift of the Pike Theatre, Herbert Lane, Dublin [fnd. 1953]; premiered 19 Nov. 1954, enjoying a six month run; Behan himself provided the voice of the central character, off-stage, singing “That Auld Triangle”; m. Beatrice ffrench-Salkeld, then working as a clerk in the Board of Works, 1955; The Quare Fellow produced in London by Joan Littlewood and Gerry Raffles at Theatre Royal, Stratford East, 24 May 1956; transferred to Comedy Theatre, West End, after three months and ran three months more; appeared drunk on a television interview, 1956; barely able to speak; diagnosed diabetic by Rory Childers on the smell of his breath in Davy Byrne’s, 1956; writes radio play, The Big House (1957), for BBC, later adapted for stage by Alan Simpson ‘with his blessing’; issued the autobiographical novel Borstal Boy (1958), publ. on 20 Oct. - which includes an account of homo-social relations which a British-navy inmate Charlie, and a fellow-IRA detainee called Callan (styled ‘a mad Republican’); | ||

| commissioned by Riobard Mac Goráin to write Irish play for Gael-Linn and produced An Giall (Damer 16 June 1958) in twelve days, a sparely-wrought tragedy concerning the IRA abduction of the English soldier Leslie who is hidden in a brothel, formerly an Anglo-Irish ‘big house’, run by Monsewer, and ultimately killed by a stray bullet; final revisions arriving (acc. Frank Dermody) scrawled on the back of cornflakes boxes; produced in English by Joan Littlewood as The Hostage (Theatre Royal, 14 Oct 1958), with elaborate overlay of contemporary reference adapted to taste of English audience; Behan horrified by changes when sober enough to appreciate them; tried for drunken disorder in Irish small town, and insisted on the hearing in Irish, March 1959; The Hostage opens in Paris, 3 April, 1959; French trans. of The Quare Fellow premiered in a translation by Boris Vian as Le Client du matin, at Théâtre de l’Oeuvre, Paris, 7 April 1959; produced by Georges Wilson, with Jean-Michel Rouzière acting; Behan travelled with Beatrice to Carraroe, but was immersed in convivial alcoholism; The Quare Fellow slated in Berlin and New York; The Hostage produced in West End (Wyndham’s Th., 11 July 1959); hospitalised in Dublin with epileptic-form fit, and discharged himself, 14 July; turned out the Dublin Christmas lights in 1959; | ||

| drinking binges at success of his play in London, interrupting performances himself; wrote article in The People admitting to his alcoholism; world wide publicity from his drunkenness; met Peter Arthurs, from Dundalk at a swimming pool in Hollywood, Arthurs becoming his companion, lover and bodyguard whenever Behan was in America; The Hostage trans. into French by E. Janvier as Les deux hostages (1961); Rae Jeffs of Hutchinson records Brendan Behan’s Island (1962), containing recorded text and stories, selected as Book of the Month, 1962 and serialised in The Observer; also Confessions of an Irish Rebel (1963), more recorded than written, and transcribed by Jeffs; becomes acquainted with American celebrities incl. Groucho Marx, Norman Mailer and Arthur Miller but later cold-shouldered by them as his reputation for heavy-drinking spreads; had an affair with young woman in New York, and an alleged child; Beatrice visits New York in May to tell him she is pregnant, but finds him in a stupor; expressed desires for Spanish boy dancers in Chelsea Hotel, New York; advocates laws to protect young from sexual abused in Brendan Behan’s New York (1964); | ||

| quit America in July 1963, having outworn his welcome in bars; platonic relationship with Edith, a Dublin prostitute; lodged with Eddie Whelan at Drimnagh; birth of his dg. Blánaid [Orla Maighread] with Beatrice; collapsed at Harbour Lights Bar, March 1964; underwent tracheotomy, 20 March 1964; received last rites; d. 20 March 1964 from sclerosis of the liver [aetat. 41]; bur. 22 March, in Glasnevin Cemetery, with an attendance of thousands; there was an IRA ceremony after the funeral; Flann O’Brien wrote his obituary in the Irish Times (‘more of a player than a playwright’); Richard Cork’s Leg, earlier rejected in 1960[?], was produced posthumously by Alan Simpson (Peacock 1972); The Bells of Hell, a celebration of Behan’s wit and wisdom, was performed by Niall Toibin and Ronnie Drew (Gaiety Th., 1974) and afterwards scripted as a film by the Sheridan brothers; this went into production up to the departure of Sean Penn from the lead role (1996); Behan is a character in the last chapter of Aidan Higgins’s Balcony of Europe (1972); | ||

| the standard biography was written b Ulick O’Connor (Brendan Behan, 1970); a new a biography by Michael O’Sullivan frankly discussing his homosexuality (1997); The Borstal Boy was premiered at the Abbey in a stage-adaptation by Frank MacMahon, under the direction of Tomás Mac Anna, 1967; won the Abbey Theatre’s first Tony Award as Best Play on Broadway and New York Circle Critics’ Award in 1970 - launching the career of Frank Grimes in the title role; Behan’s papers are held in the National Library of Ireland; there is a sculpture-portrait of Behan, seated on a bench at Binn’s Bridge on the Royal Canal, nr. Mountjoy Prison Dorset St./Whitworth Rd., Dublin; The Quare Fellow was revived by the New Theatre in 2009; Borstal Boy was staged at the Gaiety Theatre (Dublin) dir. Conall Morrison, with a playscript by Frank McMahon which introduces Behan older and Behan younger (played by Gary Lydon and Peter Coonan), Sept. 2014; Behan figures as Barney Boyle, in Christine Falls by Benjamin Black [i.e., John Banville]. DIW DIB DIL OCEL OXTH FDA OCIL WJM |

[ See Brendan Behan at the “Irish in Paris” website; accessed 29.12.2012. ]

|

|

|

| The Behan entry in the Dictionary of Irish Biography (RIA) is by Colbert Kearney - online [accessed 29.08.2023]. | |

| See ... | |

|

| Plays |

|

|

| [ top ] |

| Fiction |

|

|

| [ top ] |

| Contributions |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

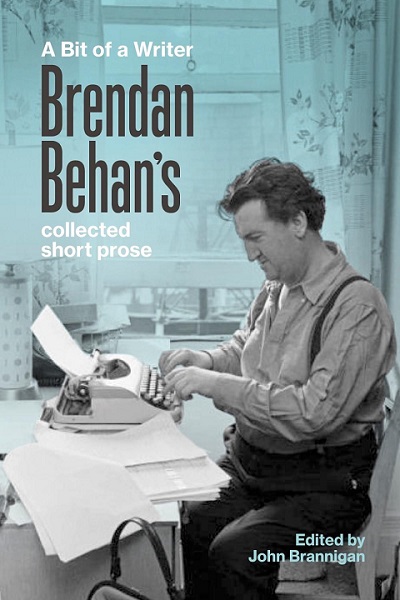

| Editions (Collected & selected) |

|

|

| [ top ] |

| Correspondence |

|

Bibliographical details

Brendan Behan’s Island (London: Hutchinson 1962; rep. 1984), 191pp., ill. Paul Hogarth; Dublin’s Fair City [11]; A Rossner, A Woman of No Standing [57]; The Warm South [67]; The Bleak West [115]; One for the Road, ‘The Confirmation Suit’ (story); The Bleak North [157]; A Couple of Quick Ones [poems in Irish and English versions, Buíochas do James Joyce/Thanks to James Joyce; Oscar Wilde, [ded.,] Do Seán Ó Suilleabháin; Epilogue, Appointed to be Read in Churches [185-91].

[ top ]

Criticism| Book-length studies |

|

| Articles & Reviews |

|

|

|

[ top ]

Commentary[ top ]

Prionsias Mac Aonghusa, ‘;Brendan Behan’s fine Irish play’, review of An Giall [premier], in The Irish Times (17 July 1959): "One expects the unusual from Mr. Brendan Behan and one is seldom disappointed. he is one of the few writers in Ireland who writes in both French and English and last night at the Damer Hall, St. Stephen’s green [sic], Dublin, he proved to an overflowing audience that he was equally at home in writing Irish. Mr. Behan’s Gaelic might not be approved by the purists, but it certainly suits the working-class Dublin of which he writes. / His new play An Giall (The Hostage) is set in a lower-class Dublin brothel owned by a fanatical Gael, the son of an Anglican bishop, who was educated at Oxford and managed by a one-legged I.R.A. man who now sees through the Republican “sham” but is willing to use it for his own ends. A young English soldier, stationed in Armagh, is kidnapped by the I.R.A. and brought to Dublin and imprisoned in the brothel. It is only by accident that he discovers that he is a hostage and will be executed by the Republican soldiers if a young man, under sentence of death in the Crumlin Road Jail, Belfast, is hanged. He falls in love with the maid of the house and she with him, and they find that both have more or less the same background - that neither cares a straw for any war or battle which Ireland and Britain might have had in the past or would have in the future. The manager of the place also understands the futility of carrying on the “old fight”, but he is powerless to intervene. / An Giall is a very cleverly-written play. Indeed, in the first act the writing was possibly too clever and the dialogue was over-loaded with witty lines that were of little use to the play as a whole. However, this was a small fault and did not detract from the over-all picture of excellence. / Mr. Behan has drawn some of the characters extremely well, particularly the prostitute, who we first meet as she bids good-bye to a Norwegian sailor, and who is admirably delineated by Nuala Nic Ghabhann. / Dealing with the present-day I.R.A. man [sic], Mr. Behan presents us with two pussyfoots who neither smoke nor drink and who flaunt their pioneer pins and their fainni. They are both puritanical and fanatical in the most vulgar possible way. Possibly Mr. Behan is correct in his appraisal of the diehards. Maybe he is wrong. But it must be admitted that he is in a better position to pass judgement on them that most. / Seamus Ó hEalaí played well in the part of the brother manager. He handled the part with a great sense of humour and off-handedness which came across admirably. Celia Salkeld as the maid was most appealing, and Noel O Briain gave a good stiff performance as the awful I.R.A. man.’ (Posted on Facebook by Niall MacDonagh, 16 09.2023.)

Seán McMahon, ‘The Quare Fellow’, in Éire-Ireland, 4, 4 (Winter 1969), pp.143-57; an article containing a significant amount of biographical information which places its study of The Quare Fellow in the context of Behan’s life and work as a whole.

Alan Simpson, ‘Behan: The Last Laugh’ [memoir], in Des Hickey and Gus Smith, eds., A Paler Shade of Green (London: Leslie Frewin 1972), pp.209-19, gives account of the production of The Quare Fellow, and the writing of An Giall: ‘We re-arranged rather than re-wrote some of the play. I still have a copy of the original script, which is very rambling. A character would change subjects as though in a genuine conversation. We made Brendan sort it out so that one subject was dealt with at a time. We probably made cuts; in fact, I am sure we did, and we tied up loose ends such as curtain lines.’ (Op. cit., p.211.) Further, ‘The Hostage was commissioned as An Giall for Gael-Linn. They gave him seventy-five pounds to write a play in Gaelic and promised him a further seventy-five pounds when it was written. He spent the first advance and wrote nothing until about three weeks before the deadline. Frank Dermody directed An Giall at the Damer hall and it was the first, if not the only, controversial play written in the Gaelic language for many a long year.’ (p.213).

Colbert Kearney, ‘Borstal Boy: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Prisoner’, in Ariel: A Review of International English Literature [ed. A. N. Jeffares], 7, 2 (1976): ‘At first sight, Brendan Behan’s Borstal Boy seems to be devoid of any structure other than simple chronology, yet this apparent carelessness is the disarming deception of the storyteller, one of the means by which the narrator makes us believe in the entirely spontaneous truth of his tale. It is quite easy to establish that the work does not contain the whole historical truth, the truth of fact, and, far from being a piece of spontaneous recounting, is the result of many beginnings and revisions. What the novel does contain is the truth of fiction: the penal institutions bear much the same relationship to Borstal Boy as the island does to Robinson Crusoe. Beneath the illusion of actuality is a structure which expresses the development of a personality. Borstal Boy is a work of creative autobiography, that genre in which the author scrutinises his formative years in the light of his later vision of himself. True to the style and scope of an oral delivery - which the novel pretends to be - the structure consists of a series of unmaskings: the narrator is perpetually posing and examining the pose. The young lad who is arrested in Liverpool has very definite views of himself and his role; these have undergone many painful changes by the time he returns to Dublin.’ (p.47.)

Colbert Kearney (‘Borstal Boy: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Prisoner’, 1976) - cont.: ‘[...] Two months in Walton Gaol had led him to question some of the extreme aspects of his career as a Republican felon. He had not changed his opinion on British imperialism but was willing to settle fro a tactical retreat from an exposed position. He would have his revenge outside; till then he did not wish to draw unnecessary attention to himself. This is presented with hilarous clarity in his encounter with Callan, a Republican from Monaghan. / Despite the fact that he was imprisoned for the theft of an overcoat, Callan was a Volunteer of extreme rigidity. No longer a believer in the brotherhood of all Irishmen, Behan finds Callan a fanatical and humorous fool who stupidly invites the warders’ wrath. Nevertheless, Callan is a genuine member of the I.R.A and this cannot be ignored. The encounter with Callan coincides with a period of great danger for Behan. In Coventry, two IRA. Volunteers were under sentence of death for bombing offences; anti-irish feeling is so hight that Behan’s chinas [ie., Cockney friends], Charlie and Ginger, stick close to him to prevent [53] a sudden attack. Callan procondemned Volunteers; Behan considers this futile, leading to nothing more than an increase in hostility and a beating from the warders. Behan is ashamed of his own fears but the desire for self-preservation is uppermost in his mind.’ (pp.53-54.) [Cont.]

Colbert Kearney (‘Borstal Boy: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Prisoner’, 1976) - cont.: ‘He tries to lose himself in the comfortable triviality of Mrs. Gaskell’s Cranford but his escape is shattered by Callan’s voice tearing through the prison. He calls on Behan to demonstrate his faith in the Republic. Behan, frightened out of his wits, curses Callan and the Republic and the overcoat which brought himself and Callan together. He will grant Callan’s courage but wishes to be excused from any heroics himself. To Callan’s repeated cries, Behan replies with a “discreet shout” and jumps back into bed. Questioned by the warders, he replies meekly that he is reading; then he listens to the groans of suffering as Callan is beaten up by the warders. The executions are due to take place the following morning. As usual in Behan’s writings, sparse prose is a sign of deep emotion. “A church bell rang out a little later. They are beginning to die now, said I to myself. As it chimed the hour, I bent my forehead to my handcuffed right hand and made the Sign of the Cross by moving my head and chest along my outstretched fingers. It was the best that I could do.” [Borstal Boy, Corgi. Edn., 1961, p.143.] Lurking in the last sentence is the uncomfortable knowledge that his behaviour, no matter how defensible, had fallen short of that prescribed for a “felon of our land.” Walton Gaol proved a hard school; Behan was perhaps lucky to escape with his life. His view of himself in terms of national and religious ideals has had to concede a great deal.’ (pp.53-54.)

Colbert Kearney (‘Borstal Boy: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Prisoner’, 1976) - cont.: ‘[...] e news of his release comes as a surprise both to Behan and to the reader. The boy at boarding-school will count the last few weeks, days, hours and minutes, but Behan does not. Also, the first duty of a prisoner of war is to escape; Behan claims that the odds against success were enormous but one feels that this is not the whole truth. Gradually one comes to the strange conclusion that the prisoner has enjoyed his prison. The governor claims that Borstal has made a man of Behan, a claim that is not disputed. It has certainly taught h im a great deal about himself and about life in general: it has sharpened his perception, taught him to use his comic gifts as a means of survival, granted him leisure to read widely and given him his first literary award. Some years later he wrote of a book: “I read this book a lot of years before it was in Penguins, at a time when I was leading a more contemplative life and had plenty of time to think about what I read.0 (Hold Your Hand [sic for Hand] and Have Another (London: Hutchinson, 1963, p. 189.) The irony does not conceal the truth and one notices the pride in an alma mater which provided such education even in pre-Penguin days. [...]’ (p.61.)

Colbert Kearney (‘Borstal Boy: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Prisoner’, 1976) - cont. [on The Quare Fella]: ‘[...] a play within a play [...] There are two audiences: those in the theatre watch those on stage who witness the externals of the closet-drama [...] The theatre audience cannot resist judging the behaviour of those on stage [...] They laugh at the black humour of the prisoners [...]. The theatre audience must realise that they have been tricked into a position which is critical of the very institution which they support outside the theatre.’ (pp.79-80; quoted in Alana Boyle, UG Diss., UUC 2011.)

[ top ]

Tim Pat Coogan considers Behan’s writing ‘like his slumland speech, fresh, uninhibited, strong and compelling’ (‘The Man Brendan Behan’, in E. H. Mikhail , ed., The Art of Brendan Behan, London 1979 [q.p.])

Declan Kiberd, ‘The Fall of the Stage Irishman’, in Ronald Schleifer, ed., The Genres of Irish Literary Revival (Dublin: Wolfhound 1980), comment on Behan’s Irish play, An Giall, and its conversion into a topical play for London audiences as The Hostage, complete with references to Profumo, and recalls Wolf Mankovitz’s remark that Behan as ‘pissed out of his mind when most of the changes were made’. (Kiberd, op. cit., p.55.)

Declan Kiberd, on reciprocal roles of English and Irish soldiers in The Hostage, writes, ‘As a lowly hostage, [the British soldier] knows that the Secretary of State in London will hardly weep into his whiskey over the loss of a single private. His captor Pat turns out to be the soldier’s secret double. One is used by the IRA, the other by the British Army; but both know that the struggle in which they are mere pawns is obsolete in an age of hydrogen bombs. In his depiction of the kilted piper Monsewer, Behan clinches the point. The cockney hostage exclaims when first he sees the old Republican: “Just like our old Colonel back at the depot. Same face, same voice. Gorblimey, I reckon it is him.’” Kiberd concludes, ‘Behan is covertly repeating Patrick Kavanagh’s suggestion that the so-called Irish Revival, like the actual Irish repression, is a plot by disaffected public-schoolboys.’ (Anglo-Irish Attitudes, Derry: Field Day 1984, p.15.)

Michael O’Sullivan, author of Brendan Behan: A Life (1997), interviewed by Shirley Kelly, in Books Ireland (Dec. 1997), pp.325: O’Sullivan reflects that the biography arose from student-days friendship with Beatrice Behan while O’Sullivan was in TCD and frequenting Donnybrook pubs; incl. materials such as his letters from borstal in British archives, saved in 1967 by vigilant clerk, and not due for release until 2007.

Hugh Oram, reviewing Brian Behan, The Brothers Behan (1999) in Books Ireland (Oct. 1999), relates anecdotes: Behan’s reputed last words, to the nun caring for him, ‘May you be the mother of a bishop’; John Ryan’s views on Behan’s polymorphous sexuality to the effect that he would get up on the back of the Drimnagh bus; Behan’s remark to Tony O’Reilly after the Rugby international, ‘I was going to send in Beatrice after you, but when I saw what was on show in the shower, Jaysus, I thought I’d never get her back again’; remark on the difference between states, ‘From one, you’ll get an eviction order written in English with the lion and unicorn and from the other you’ll get an eviction order written in Irish, with a harp’; Behan called Kavanagh ‘the fucker from Mucker’; also a story of John Charles McQuaid’s visit to Kavanagh on an errand of mercy at a moment when Kavanagh was in bed with a lady of the night, who roars from the window …; considers the book a useful addition to the Behan bibliography. (BI, pp.280-81.)

Independent [UK] (5 Oct. 1994), notice of The Hostage at the Barbican [London]: ‘Behan’s uproarious tragedy about the Irish elevation of causes above human life still sings and stings; Dermot Crowley and John Woodvine head a strong cast set in ‘the hole’, a tenement in Nelson St., where the hostage, a British soldier, dies of suffocation in the cupboard during the final raid on the house; based on story of British Tommy captured at Ballykinlar Camp, Co. Down, 1955, and another event in which young soldiers [were] killed in an ambush of 1921; deals with Partition, revival of Irish, and de Valera’s haughty attitude; among ten characters are Monsúr, the Anglo-Irish Irish patriot.

[ top ]

Fintan O’Toole, ‘Culture Shock: Brendan Behan - playwright, novelist, terrorist’, in The Irish Times (6 Sept. 2014), Weekend Review - on Behan’s bombing mission in Britain: ‘[...] Behan’s mission in Liverpool came after the Coventry atrocity and also after the start of the second World War. [Everyday bombings in English cities during 1939.] Whatever demented logic there had previously been to the campaign was now completely lost. [...] There was nothing “revolutionary” about any of this. [... T]he evil Brits deprive him of the glory of martyrdom by treating him remarkably well. / In some ways what happened to Behan is scarcely credible by today’s standards. In an atmosphere of panic induced by a year-long bombing campaign, and facing into an existential struggle against the Nazis, the English system could almost be forgiven for maltreating Behan. He was indeed roughed up a bit by the police, but for the most part he received justice. He got a fair and open trial. And he was treated as a child - something that would not happen in similar circumstances in, say, the US today. Remarkably, Behan was kept out of the adult prison system and sent to a borstal. These were not holiday camps, but they were reasonably enlightened institutions with an emphasis on rehabilitation - a good deal safer and more decent than their industrial-school equivalents back home in dear old Ireland. / And this is the great drama of Borstal Boy. It captures the mind of a child terrorist trying to cope with the shock of kindness.’

[ top ]

|

Some poems ...

| “The Laughing Boy” | |

|

|

| “On the Eighteenth Day of November ...” | |

|

On the Eighteenth Day of November |

But the boys of the column were waiting |

| “Open the Window Softly” | |

|

|

| —The foregoing poems are available at Beingpoet blogspot (11.02.2012) - online; accessed 11.01.2018. | |

[ See also Behan’s “Búichas to James Joyce” (a toast) - as attached. ]

[ top ]

Drama

The Quare Fellow (1960): ‘I smoked my way half-way through the book of Genesis and three inches of my mattress. When the Free State came in we were afraid of our live [sic] they were going to change the mattresses for feather beds.... But sure, thanks to God, the Free State didn’t change anything more than the badges in the warders’ caps.’ (The Quare Fellow, 1960, p.21; cited in Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation, London: Jonathan Cape 1995, p.515.) Further, ‘You wouldn’t mind old Silver-top. Killing your wife is a natural class of a thing could happen to the best of us. But this other dirty animal on me left ...’ [referring to a sexual offender] (The Quare Fellow, p.43); ‘it’s a soft job, sir, between hangings.’ (The Quare Fellow, p.71.)

| The Quare Fella - (before the hanging): |

| WARDER REGAN: Well, I shall be with the condemned man sir, seeing that he doesn’t do away with himself during the night and that he goes down the hole with his neck properly broken in the morning, without making too much fuss about it. HEALEY: A sad duty. WARDER REGAN: Neck breaking and throttling, sir? (Healy gives him a sharp look.) You must excuse me sir. I’ve seen rather a lot of it. They say familiarity breeds contempt. HEALEY: Well, we have one consolation, Regan, the condemned man gets the priest and the sacraments, more that his victim got maybe. I venture to suggest that some of them die holier deaths than if they had finished their natural span. WARDER REGAN: We can’t advertise “Commit a murder and die a happy death,” sir. We’d have them all at it. They take religion very seriously in this country. (The Complete Plays, 1978, p.67.) |

| [...] |

| REGAN: I walked beside them and guided the boy on to the trap and under the beam. The rope was put round him and the washer under his ear and the hood pulled over his face. And still the young clergyman called out to him, in a grand steady voice, in through the hood: “I declare to you my living Christ this night...” and he stroked his head till he went down. Then he fainted; the Canon and myself had to carry him out to Governor’s office. (The Complete Plays, (1978) p.101. |

| Also: ‘If he gave him too much one way he’d strangle him instead of breaking his neck, and too much the other way he’d pull the head clean off his shoulders’. ( The Complete Plays, 1978, p.130) |

| —The foregoing all quoted in Alana Boyle, UG Diss., UUC 2011. |

| [Q. speaker:] ‘then the Free State came in and we were afraid of our life they were going to change the mattresses for feather beds ... But sure, thanks be to God, the Free State didn’t change anything more than the badges in the warders’ caps.’ (Quoted quoted in Eugene O’Brien, ‘Ireland in Theory: The Influence of French Theory on Irish Cultural and Societal Development’, ‘Kicking Bishop Brennan Up the Arse’: Negotiating Texts and Contexts in Contemporary Irish Studies, Bern: Peter Lang 2009, p.13.) |

[ top ]

Borstal Boy (1958): ‘I was not country Paddy from the middle of the Bog of Allen to be frightened to death by a lot of Liverpool seldom-fed bastards, nor was I one of your wrap the green-flag-round me junior Civil Servants that came into the IRA from the Gaelic League, and well ready to die for their country any day of the week, purity in their hearts, truth on their lips, for the glory of God and the honour of Ireland’ (Borstal Boy, p.78). Behan remarked of the play: ‘It’s the story of an Irish boy of sixteen arrested and sentenced in England for IRA activities, of his fears, hopes and relationships with the other boys in an English reformatory. It is a book of innocence and experience’ (cited in Letters of Brendan Behan, E. H. Mikhail, ed., Toronto: McGill-Queen’s UP 1992, p.114.)

An Giall: ‘I saw the rehearsals of An Giall and, while I admire the producer, Frank Dermody, tremendously, his idea of a play is not my idea of a play. He’s of the school of Abbey Theatre naturalism, of which I’m not a pupil. Joan Littlewood, I found suited my requirements exactly. She has the same views on the theatre as I have, which is that the music hall is the thing to aim at for to amuse people and any time they get bored, divert them with a song or a dance. I’ve always thought T. S. Eliot wasn’t far wrong when he said that the main problem of the dramatist today was to keep his audience amused; and that while they were laughing their heads off, you could be up to any bloody thing behind their backs; and it was what you were doing behind their bloody backs that made you[r] play great’ (Quoted in Colbert Kearney, The Writings of Brendan Behan, p.130; also more fully in Declan Kiberd, ‘Introduction’ to Brendan Behan, Poems and a Play in Irish, Gallery Press, 1981, p.11; and in Anthony Roche, Contemporary Irish Drama, 1996, p.65 [citing Kiberd]).

| “The Captains and the Kings” (from The Hostage, 1958) | ||||

|

|

|||

| —The Hostage (Bloomsbury 2014) - online; access 11.01.2018. | ||||

| Cf. Rudyard Kipling’s “Recessional” (1897) | ||||

|

If, drunk with sight of power, we loose For heathen heart that puts her trust |

|||

| —Poetry Foundation - online; accessed 11.01.2018. | ||||

[ top ]

Sundry Remarks

Behan in the dock (Nov. 1939): ‘It is my proud privilege and honour to stand in an English court to testify to the unyielding determination of the Irish people to regain every inch of our national territory, and to give expression to the noble aspirations for which so much Irish blood had been shed and so many hearts have been broke, and for which so many friends and comrades are languishing in English jails”.(Brendan Behan, Interviews and Recollections Vol. 1,1982, p.10; quoted in Alana Boyle, UG Diss., UUC 2011.)

Irish & English: ‘Irish is more direct than English, more bitter. It’s a muscular fine thing, the most expressive language in Europe’ (cited in O’Connor, Brendan, p.193). On Fame, Behan said: ‘They’d praise my balls if I hung them high enough’ (Ulick O’Connor, Brendan, p.244).

Church & Nation: ‘I didn’t spend a lifetime studying theology, but I know that the Church was always against Ireland and for the British Empire.’ (Borstal Boy, p.74; cited Noël Debeer, ‘The Irish Novel Looks Backward’, in Rafroidi and Maurice Harmon, eds., The Irish Novel in Our Time, Université de Lille 1975-76, pp.106-23, p.114. Further, Behan said of his own Catholicism that it ‘went back to the Mass Rock and the poems of [Tadhg] O’Sullivan, not to the pious intellectualism of Newman and his ilk.’ (Quoted in Gaelic Literature’, Dictionary of Irish Literature, 1979; Quoted in P. J. Kavanagh, Voices in Ireland, 1994, p.113.)

Behan/Beckett (I): ‘When Sam Beckett was in Trinity College listening to lectures, I was in the Queen’s Theatre, my uncle’s music hall. That is why my plays are music hall and his are university lectures.’ (Quoted in D. E. S. Maxwell, A Critical History Of Modern Irish Drama 1891-1980, 1984, p.150) [See also Loreto Todd, The Language of Irish Literature, 1989, p.76.]

Behan/Beckett (II): See also remarks in interview with Sylvère Lotringer, regarding the use the the “f****” word in ordinary English: ‘if you were to ask Mr Samuel Beckett about that, who is a friend of mine incidentally, he would say that what I was not saying is not true. That’s because he hasn’t been in the habit of hearing it.’ [See full text as infra].

[ top ]

References

The Oxford Companion to Theatre remarks upon the powerful influence of Brecht to be found in Behan’s work.

D. E. S. Maxwell, A Critical History of Modern Irish Drama 1891-1980 (Cambridge UP 1984), contains remarks on pp.xiii, 150-54, 160, 220, 223; also The Hostage ( An Giall) pp.xiii, 153, 155; ‘Moving Out’, p.220; The Quare Fellow p.xiii, 149, 150-55; Borstal Boy p.160.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), 3, references to Breandán Ó Beacháin, pp.175-76; The Quare Fellow extract, pp.201-31; see also pp.232; 247n; 382; 523-28; 530-35; 656-57; 817; selects “Jackeen ag Caoineadh na mBlaosaod [A Jackeen Laments the Blaskets]”, p.909; selects “Do Sheán Ó Súilleabháin” and “Oscar [Wilde]”, pp.910; further at 1137; 1311.

Grattan Freyer, A Prose And Verse Anthology Of Modern Irish Writing (Dublin: Irish Humanities Centre/Ballina: Keohane’s Ltd/Gerrards Cross: distributed by Smythe 1979), [contains The Big House, one-act radio play].

Donal Nevin, ed., Trade Union Century [RTE with Irish Congress of Trade Unions] (Cork: Mercier 1995), contains a poem on Jim Larkin by Brendan Behan.

Brendan Kennelly, intro., Landmarks of Irish Drama (London: Methuen 1988), contains The Quare Fellow, with works of Shaw, Yeats, Synge, Johnston, and Beckett. Appendix includes 1 page of Gaelic version.

[ top ]

Notes

Muggeridged: Constantine FitzGibbon writes in a reply to Conor Cruise O’Brien’s review of her life of Dylan Thomas, in NY Review of Books ‘[...] As for the Behan television incident, Mr. FitzGibbon should have a look at the gleeful article which Mr. Muggeridge published on that subject, in the New Statesman, just after Behan’s death.’ (NYRB, 3 Feb. 1966.) FitzGibbon had quoted O’Brien and commented to this effect: ‘He states that Mr. Muggeridge deliberately got Brendan Behan drunk before a television interview in order to make a mock of “an artist” for the delectation of a philistine and even murderous public, our old friends “the bourgeoisie.” In fact Behan was drunk long before he went to the Television Center, having reached that condition in a club which Dr. O’Brien also frequents on the occasion of his visits to London: when members of that club realized that he was to appear on television, they attempted to persuade him that he plead sickness, but Brendan Behan insisted on going, because he wished to insult the English public by shouting obscenities at the cameras: at the Television Center, Mr. Muggeridge and BBC officials attempted, and failed, to sober him up: without the stimulus of further drinks, he sank into a glazed semi-coma, and said nothing.’ (Idem.)

Prompt: Behan was prompted to write his play The Quare Fellow by the story of Bernard Kirwan, hanged in 1943 for murdering his brother the previous year. It was one of the first dramas to oppose capital punishment. (Irish Times, 12, Nov. 1995, review of Thou Shalt Not Kill, RTÉ1 a series on eleven murder cases.)

Horsemen ...: Behan’s celebrated definition of an Anglo-Irishman as ‘a Protestant with a horse’ falls in the dialogue between Meg, Pat - who supplies the information - and Ropeen in The Big House. Pat continues, ‘... an ordinary Protestant like Leadbetter, the plumber in the back parlour next door, won’t do, nor a Belfast Orangeman, not if he was as black as your boot. [...] An Anglo-Irishman only works at riding horses, drinking whisky and reading double-meaning books in Irish at Trinity College.’ (“The Hostage”, in The Complete Plays. New York: Grove Press, 1978, p143; quoted in Alan Warner, A Guide to Anglo-Irish Literature, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1981, p.24; also in James Wurtz, ‘A Very Strange Agony: Modernism, Memory and Irish Gothic Fiction’, Ph.D., Notre Dame U., 2005 [online].)

[ top ]

The Bell: Anthony Roche identifies Behan’s contribution to the Bell as ‘Experiences of a Borstal Boy’, in Contemporary Irish Drama From Beckett to McGuinness (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1996, p.43.)

AC/DC: According to Anthony Cronin, Behan admitted to a ‘Herod complex’ - i.e., a sexually-indiscriminate love of youth (see Cronin, Dead as Doornails, Dublin: Dolmen 1975, p.9).

Laid up: On Friday 8 Nov. 1963, Brendan Behan was said to be ‘reasonably comfortable’ in the Royal City of Dublin Hospital, Baggot St., having been admitted on Wednesday that week. (Report on the front page of The Irish Times, 8 Nov. 1963; rep. form IT Archive in The Irish Times, 19 Dec. 2009, Weekend, p.14.)

Portrait: Harry Kernoff, ‘Brendan Behan’, Adams (Blackrock), £2,100; also a life size figure on a bench on the Royal Canal, Dublin [?q. author].

The Hostage, revived at New Theatre, Temple Bar (Dublin), at 40th centenary of the playwright’s death, with cast including Anthony Fox, Terence Orr, Joe Cassidy and Laoisa Sexton.

[ top ]

Criticcccc! David Norris recalls a bon mot pronounced by Behan: ‘[...] in response to a some timid query frm my schoolboy self the late Brendan Behan opined that “the critic is like a eunuch in a harem. He sees the job done every night but he can’t do it himself.’ (‘Imaginative Response versus Authority: A Theme of the Anglo-Irish Short Story’, in The Irish Short Story,ed. Terence Brown & Patrick Rafroidi, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1979, p.49.)

Daddy, Daddy!: ‘Brendan Behan fathered a son, also Brendan, with Valerie Hemingway (née Danby Smith) during a one-night stand in San Francisco; the boy was raised by Valerie with Gregory Hemingway, the transexual son of Ernest whom she served as secretary (and later his daughter Mary after Hemingway’s death); Gregory had been disowned by his father after revelations about his transvestite behaviour and numerous electro-shock treatments during the long-undiagnosed ‘illness’; divorced Valerie after two decades during which three other children were produced; Gregory died of heart disease in a women’s cell in Miami following charges of ‘indecent exposure’. Danby-Smith was the dg. of an Anglo-Irish family, raised in Stillorgan, and sent to boarding school in Ireland; attended secretarial college in Dublin and left for Spain, sending reports to The Irish Times; friendly with Terry Cronin, wife of the IRA-chief; interviewed Hemingway and recruited to his caudrilla (set), attending bullfights with him in summer of 1959 following mano a mano bullfights of Spain’s leader matadors; taken back as secretary to Havana, and involved in negotiations with Castro after Hemingway’s suicide in Idaho to recover the contents of his house (papers and paintings) in exchange for the house itself.’ (See George Dempsey, “An Irishman’s Diary”, in The Irish Times, 7 Jan. 2006, p.17.)

Kith & Kin: Paudge Behan, an actor, is the son of Brendan Behan’s widow Beatrice Behan with Cathal Goulding, former chief of staff of the ‘Official’ IRA and sometime partner of Maire Woods. Woods is the widow of (“Bobbie”) Woods and well-known ENT surgeon and himself the son of Sir Robert Woods - knighted by Victoria for services to medicine. She herself a pediatrician whose anxiety about child abuse led to false accusations and the suspension of her practitioners certificate. Considerably younger than her husband, she was at first his secretary in his Fitzwilliam practice. As his widow she acquired a Georgian house on St Stephen’s Green which was leased by the British Govt. as its Dublin embassy and was destroyed by fire during a political protest fueled by public indignation at the events in Derry in Jan. 1972 (“Bloody Sunday”). The burning of the embassy was ascribed to the Provisional IRA. In c.2005, Paudge sold up the family home in Ballsbridge and moved to Arcodossi, a small town in Italy. In July 2008 he appeared in Italian TV to deny that he was responsible for the stabbing of the elderly Silvana Abate who was murdered in her Arcidossi home On being reported to the police by the local hospital where he presented himself with a knife-wound to the thigh, he asserted that he had injured himself while preparing medicine.

[ top ]