Life

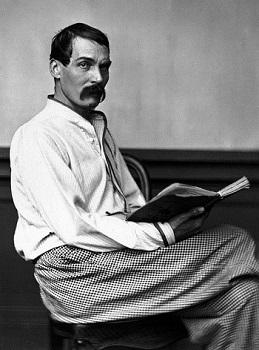

| 1821-90; b. 9 March, at Torquay, Devon; [by his own account at Barham Hse., Estree, Herts., the home of his maternal grandfather, Richard Baker]; son of a Lieut.-Col. Joseph Netterville Burton (36th Regt.), Anglo-Irish, and an English mother of Neterville descent; his paternal grandfather was a Galway rector at Tuam, Co. Galway, and later Bishop of Killaloe; travelled in France and Italy during childhood, led by his asthmatic father’s quest for better climates; matriculated at Trinity College, Oxford, where he was noted for duelling, riding, smoking, gambling - experimenting with various forms of wildness; eventually sent down for attending a steeple-chase (he notified the authorities to goad them); obsessive aptitude for languages, especially Arabic; joined the East Indian Army in 1842 at Bombay under Gen. Charles James Napier; and served briefly in the Crimean War; |

| he learned to use the Indian sword and lance and set off on wide travels in India and beyond; his friendship with Indians and his Indian mistresses earned him the sobriquet of ‘white nigger’ from brother-officers; his departure from the Army purportedly precipitatd by Napier’s reaction to the uncomfortably accurate account he gave of boy-brothels in Karachi in a report [var. sought release from the Army from the Company to travel]; travelled to Mecca as Hajji Abdullah, 1853; received javelin wounds in the cheek during encounter with Somali tribe in company with John Hanning Speke, then newly-arrived in Africa; arriving at Ujiji, he sighted Lake Tanganyika, with Speke, 4 Feb. 1858 - but was beaten in bringing news to the Royal Geographical Society by Speke - who also sighted Lake Nyanga Victoria; |

| issued Personal Narrative (1855); a public debate between the men due to be held on 16 Sept. 1864 failed to materialise due to Speke’s death in a shooting accident at his country home the day before; received consular appointment, India, 1861, and served as British consul in Fernando Po (West Africa) up to 1864, travelling traveled widely between Ghana and Angola; m. Isabel Arundell, who wrote his life in 1893, 1861; appt. consul in Santos in Brazil (1865) and afterwards at Damascus (1869), and Trieste (1871); issued Book of the Sword (1884); trans. 1001 Stories of Arabian Nights (1885-88), with a “terminal essay” detailing history and practice of homosexuality; posthumous incl. trans. of ‘Catullus’ and ‘Pentamerone’; involved in publication of Kama Sutra; also The Perfumed Garden of Cheik Nefzaoui’; also translated the Lusiads of Camoens (1880); |

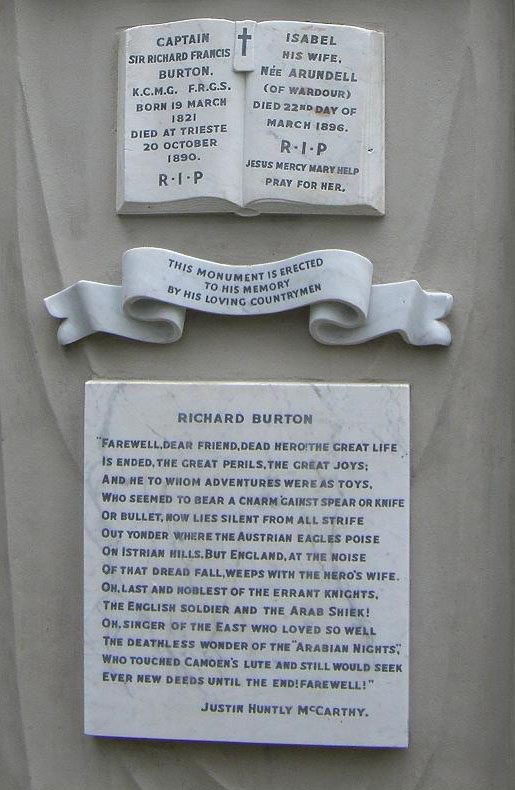

| issued revised edn. of Arthur Leared’s Morocco and the Moors [1876] (1891); during his travels he learned languages including Hindustani, Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, Maratha, Gujerati, and Persian, with his European languages, amounting to 29; converted to Tantric Brahmanism, then Sikhism, then Islam; knighted KCMG, in 1886; also FRGS; his Sindh Revisited is a well established school text in Pakistan; d. in Trieste, where he was consul, 20 Oct, 1890; buried at Mortlake (London) in a tent-shaped tomb with crucifix and Islamic crescent, erected by his ‘loving countrymen’ with verses by Justin Huntley McCarthy in an attached plaque; some papers connected with a new translation of The Perfumed Garden destroyed by his wife, who also arranged Catholic extreme unction at his death [or after it], to the dismay of friends; Burton is included in Eminent Victorians by Lytton Strachey; Burton is considered a contributory model to the portrait of Dracula in Bram Stoker’s novel of that name [see infra]. CAB ODNB JMC OCEL OCIL |

[ top ]

Works

|

|

|

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Scinde : or, The unhappy valley [...] In two volumes (London Richard Bentley 1851), 2 vols [viii, 297, [1]; vi, 309, [1]p. ; 8°. To the Gold Coast for Gold: A Personal Narrative [with Verney Lovett Cameron] (London: Chatto & Windus 1883), xii, [2], 354pp.; vi, 381, [1]p., ill. [2 folding maps; col. frontis.], 20 cm. [see extract]. A mission to Gelele: king of Dahom[ey]: with notices of the so called ‘Amazons,’ the grand customs, the yearly customs, the human sacrifices, the present state of the slave trade, and the NegrO’s place in nature (London: Tinsley Brothers 1864), 2 vols., ill. 20cm. Two trips to gorilla land and the cataracts of the Congo (London Sampson Low, Marston, Low and Searle 1876), 2 vols. The Book of the thousand nights and a night: a plain and literal translation of The Arabian nights entertainments ... with introduction explanatory notes on the manners and customs of Moslem men and a terminal essay upon the history of The Nights by Richard F. Burton (Printed by The Burton Club for private subscribers only [1885?-1886?]), 10 vols., ill.; 25cm. [‘Bagdad edition. Limited to one thousand numbered sets, of which this is number 458’; ‘Benares edition’ on spine; incls. 7 vol. of the Supplemental nights Pub. dates taken from translator’s forword and dedications. [Johnson collection; SOAS UL] Lady Burton’s edition of her husband’s, Arabian nights, prepared for household reading by J.H. McCarthy (London 1886), 6 vols., 8° The Kasîdah of Hājî Aboû El-Yezdî: a lay of the Higher Law. Translated and annotated by ... F. B. [i.e. Frank Baker, pseudonym of Sir R. F. Burton] (London: Bernard Quaritch 1880), 33pp. The perfumed garden of the Cheikh Nefzaoui : a manual of Arabian erotology, translated by Sir Richard F. Burton, with an introduction by Mary S. Lovell (NY: Signet Classic [1999]), xx, 219 p ; 18 cm ... See COPAC > “Richard Francis Burton” - online; accessed 16.09.2018. Available on Internet ....

| The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885-88), trans. by Richard F. Burton | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

See also the website:

|

|

||||||||

There is a copious Wikipedia entry on Burton [online - accessed 16.09.2018.] See also remarks on Burton and ‘slave beads’ in The Beading Game by Pearl Bay [online - accessed 16.09.2018].

[ top ]

Criticism| Older biography | ||

|

||

|

||

| Newer Biography | ||

|

||

| Studies incl. | ||

|

Bibliographical details

Fawn Brodie, The Devil Drives: A Life of Sir Richard Burton (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode 1967), 390pp.; Do. (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1971), 505pp.; Do. (NY: Norton 1984), 390pp., 16pp. pls.; Do. (London: Eland 1990), 390pp., and Do. (London: Eland 2002), vii, 464pp.

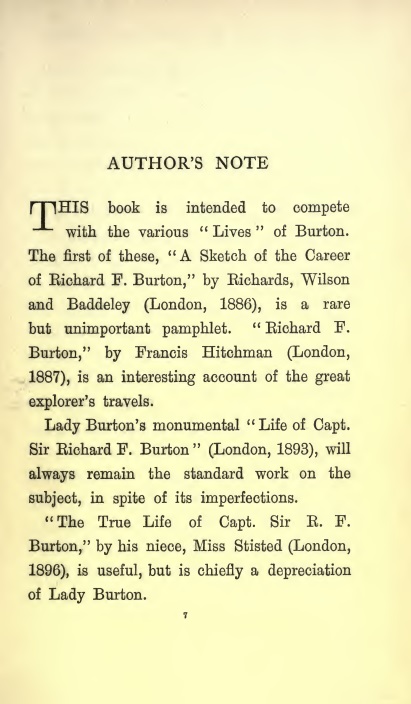

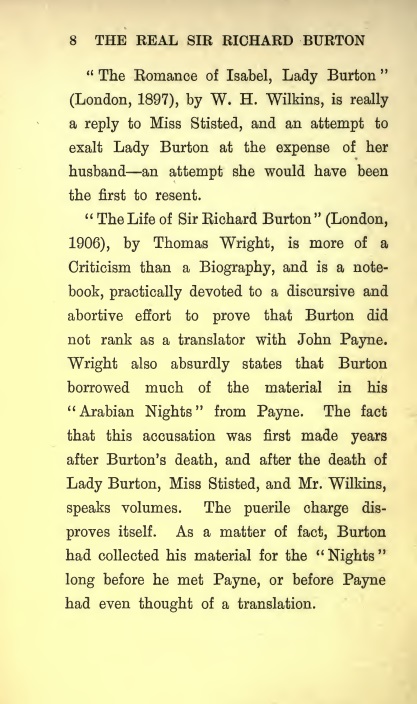

Walter Phelps Dodge, The Real Sir Richard Burton ( London: T. Fisher Unwin 1907)

Available at Burtoniana.org - online [accessed 16.09.2018] - and therin characterised as defense of Burton with several errors and ‘not worth bothering about’ - but reproduced here for the bibliogr-aphical details supplied in the Author’s Note.

[ top ]

Commentary

Frank McLynn, ed. Of No Country: An Anthology of the Works of Sir Richard Burton (1991) [selected]; ‘travelled to Mecca disguised as an Afghan doctor; travelled with John Hanning Speke in Somaliland, wounded in the face by a spear during an attack on camp, leaving an extraordinary scar; spoke many languages; ed. Oxford where he was treated with phenomenal stupidity; married a Catholic, also of Irish extraction, who shared his passion for adventure’.

Amit Chaudhuri, reviews of Christopher Ondaatje, Sind Revisited: A Journey in the Footsteps of Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton 1842-1849 (London: HarperCollins [?1996]), 351pp.; gives Herefordshire as Burton’s birthplace; discusses his career [as above] and his influence on Kipling; notes that he married the faithful and staunchly Catholic Isabel Arundell in 1861; the author of the book has followed Burton on his travels, though usually assisted by local police and businessmen and copiously luncheoned; his style (‘everywhere my attention was grabbed ...’) is not admired. (Times Literary Supplement, 26 July, 1996, p.11.)

Malise Ruthven, ‘A Very Curious Marriage’, review of Mary S. Lovell: A Rage to Live: A Biography Richard and Elizabeth Burton (1998), in Times Literary Supplement, 25 Dec. 1998, p.3; documents fully the author’s attempt to show that their private life was happier than supposed from readings of his sexuality as homoerotic and predatory, and critical of previous works by Brodie and McLynn; photo of Burtons at Madeira in 1863.

Michael Saler, ‘Eminence to Spare’, review of Dane Kennedy, The Highly Civilised Man: Richard Burton and the Victorian World in Times Literary Supplement, 9 Dec. 2005), p.23: ‘[...] Burton’s career also demonstrates that the Victorians’ attempts to define and fix difference could be used to undermine their own sense of cultural superiority. He did not hesitate to compare Evangelicalism with non-Western religions, usually to the detriment of the former, contemporaries were shocked to find him praising polygamy and Islamic traditions providing women with certain freedoms difficult to attain in the West. And he became a crusader for sexual freedom in the 1880s, a “harbinger of the modern sexologists”, according to Kennedy. Burton used his translations of the Kama Sutra, The Perfumed Garden, the Arabian Nights, and other texts to show that the Oriental world encouraged a greater degree of sexual fulfilment for both women and men than was possible in the puritanical Occident. [...] Burton’s experiences are used as a springboard to provide cogent insights into “Orientalism”, the emergence of biological conceptions of race and the countervailing forces of cultural relativism, the tensions between armchair geographers and explorers,the debates between science and religion (Burton practised mesmerism and investigated spiritualism), and the gradual transition from Victorian to modern ideas about sexuality. / Kennedy argues that in many respects Burton presaged our own modernistic concerns about the instabilities of hierarchical oppositions and the contingent construction of cultural difference. At times, though, his Burton seems too contemporary, even postmodrn. Burton, he writes, was reluctant “to commit to a stable and readily identifiable identity” because he enjoyed “transcending the conventional boundaries of religion and race”. Untutored in the postmodernism discourses of hybridity and mimicry, Burton’s contemporaries would simply have said he was iconoclastic. [...] Lytton Strachey was right not to include him as an Eminent Victorian when he could just as easily be pegged as an Eminent Modern. [End]’

Burton’s wound: Account of Burton’s encounter with Somali tribesmen under John Hanning Speke in Wikipedia: ‘In 1854 he [Speke] made his first voyage to Africa, first arriving in Aden to ask permission of the Political Resident of this British Outpost to cross the Gulf of Aden and collect specimens in Somaliland for his family’s natural history museum in Somerset. This was refused as Somaliland was considered rather dangerous. Speke then asked to join an expedition about to leave for Somaliland led by the already famous Richard Burton who had Lt William Stroyan and Lt. Herne recruited to come along but a recent death left the expedition one person short. Speke was accepted because he had traveled in remote regions alone before, had experience collecting and preserving natural history specimens and had done astronomical surveying. Initially the party split with Burton going to Harrar, Abyssinia, and Speke going to Wadi Nogal in Somaliland. During this trip Speke experienced trouble with the local guide who cheated him and after they returned to Aden, Burton who had also returned, saw that the guide was punished and jailed and killed. This incident probably led to larger troubles later on Now all 4 men traveled to Berbera on the coast of Somaliland from where they wanted to trek inland towards the Ogaden. While camped outside Berbera they were attacked at night by 200 spear wielding Somalis. During this fracas Speke ducked under the flap of a tent to get a clearer view of the scene and Burton thought he was retreating and called for Speke to stand firm. Speke did so and then charged forward with great courage shooting several attackers. The misunderstanding of this incident laid the foundation of their disputes and dislikes much later. Stroyan was killed by a spear, Burton was seriously wounded by a javelin impaling both cheeks and Speke was wounded and the only one captured, Herne came away unwounded. Speke was tied up and stabbed several times with spears, one thrust cutting through his thigh along his femur and exiting. Showing tremendous determination he used his bound fists to give his attacker a facial punch and this gave Speke an opportunity to escape, albeit he was followed by a group of Somalis and he had to dodge spears as he was running for his life. Rejoining Burton and Herne the trio eventually managed to escape with a boat passing along the coast. The expedition was a severe financial loss and Speke’s natural history specimens from his earlier leg were used to make up for some of it. Speke handed Burton his diaries that Burton used as an appendix in his own book on his travels to Harrar. It seemed unlikely that the two would join again and Burton believed that he would not lead an expedition to the interior of Africa, his fervent hope, after this failed journey.’ (Wikipedia - online; accessed 16.09.2018.)

[ top ]

Quotations

Preface to Arabian Nights (1885): ‘[...] In accordance with my purpose of reproducing the Nights, not virginibus puerisque, but in as perfect a picture as my powers permit, I have carefully sought out the English equivalent of every Arabic word, however low it may be or “shocking” to ears polite; preserving, on the other hand, all possible delicacy where the indecency is not intentional; and, as a friend advises me to state, not exaggerating the vulgarities and the indecencies which, indeed, can hardly be exaggerated. For the coarseness and crassness are but the shades of a picture which would otherwise be all lights. The general tone of The Nights is exceptionally high and pure. The devotional fervour often rises to the boiling point of fanaticism. The pathos is sweet, deep and genuine; tender, simple and true, utterly unlike much of our modern tinsel. Its life, strong, splendid and multitudinous, is everywhere flavoured with that unaffected pessimism and constitutional melancholy which strike deepest root under the brightest skies and which sigh in the face of heaven: Vita quid est hominis? Viridis floriscula mortis; Sole Oriente oriens, sole cadente cadens.’ [Cont.]

Preface to Arabian Nights (1885): ‘[...] with the aid of my annotations supplementing Lane’s, the student will readily and pleasantly learn more of the Moslem’s manners and customs, laws and religion than is known to the average Orientalist; and, if my labours induce him to attack the text of The Nights he will become master of much more Arabic than the ordinary Arab owns. This book is indeed a legacy which I bequeath to my fellow countrymen in their hour of need. Over devotion to Hindu, and especially to Sanskrit literature, has led them astray from those (so called) “Semitic” studies, which are the more requisite for us as they teach us to deal successfully with a race more powerful than any pagans - the Moslem. Apparently England is ever forgetting that she is at present the greatest Mohammedan empire in the world. Of late years she has systematically neglected Arabism and, indeed, actively discouraged it in examinations for the Indian Civil Service, where it is incomparably more valuable than Greek and Latin. Hence, when suddenly compelled to assume the reins of government in Moslem lands, as Afghanistan in times past and Egypt at present, she fails after a fashion which scandalises her few (very few) friends; and her crass ignorance concerning the Oriental peoples which should most interest her, exposes her to the contempt of Europe as well as of the Eastern world. When the regrettable raids of 1883-84, culminating in the miserable affairs of Tokar, Teb and Tamasi, were made upon the gallant Sudani negroids, the Bisharin outlying Sawakin, who were battling for the holy cause of liberty and religion and for escape from Turkish task-masters and Egyptian tax-gatherers, not an English official in camp, after the death of the gallant and lamented Major Morice, was capable of speaking Arabic. Now Moslems are not to be ruled by raw youths who should be at school and college instead of holding positions of trust and emolument. He who would deal with them successfully must be, firstly, honest and truthful and, secondly, familiar with and favourably inclined to their manners and customs if not to their law and religion. We may, perhaps, find it hard to restore to England those pristine virtues, that tone and temper, which made her what she is; but at any rate we (myself and a host of others) can offer her the means of dispelling her ignorance concerning the Eastern races with whom she is continually in contact.’ [See full copy of the Burton’s Foreword, along with some other critical material relating to the later translation by John Payne and the relation between the two - attached].

[ top ]

|

|

|

|

Available at Google Books - online; accessed 221.0.2012 |

[ top ]

References

Dictionary of National Biography [ODNB]: Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821-1890), born at Barham House, Hertfordshire [err.], educated privately and Trinity College, Oxford; learned Arabic through introduction to Spanish scholar; rusticated; joined army, 1842; round Cape, June; landed Bombay; consular appointment, India, 1861; passed exams in Hindustan; joined the Indian Army in 1842; good graces of Charles Napier; Sindh survey; commission to wander in India; attached to private teachers, ‘like a white nigger’ acc. brother officers; Burton travelled to Mecca, Arabia; wrote report on private life of Indian natives for Napier, prob. interfered with advancement; Africa, Russia; twice tried to engage in Sikh War; acted as British consul in Brazil, Damascus, and in Trieste, where he died; returned to England, 1849, with large collection of MS; linguistic publications in London schol. journals; brought out in 1851 several Sind books; also work on falconry in the Indus Valley and military works; maître des armes (fencing); met future wife at Boulogne; travelled to Arabian in disguises, including Al Hajj traveller Ab[d]ullah; 17 July-23 Sept., many travel books include Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to El-Medinah and Meccah 3 vols. (1855-56), 4 edns.; returned to India, 1856; Crimea 1855 leave of absence, with Speke on Nile; pioneering trip to Harare; wounded in attack on camp in Somaliland; sight of Lake Tanganyika, 14th Feb. 1858; sighted Victoria Nyanza; estranged from Speke on difference over source of Nile; Royal Geog. Medal; engagement not recognised by wife’s family; rapid run across N. America, producing book on City of the Saints (1861); m. Isabel Arundell, 1861, in Catholic chapel, 22 Jan.; families reconciled; his interest in erotica leads to translations of the Kama Sutra (1883), The Perfumed Garden (1886), and The Arabian Nights (1885-88). [See full entry - attached.]

Isabel Arundel: There is a separate ODNB entry on his wife Isabel Arundell (1831-1896) - of Catholic family; descended from hereditary count of Papal Empire; m. Burton at Boulogne; mixed marriage permitted by Cardinal Wiseman; sec. and aide de camp of husband; except Arabian Nights [?err. for Kama Sutra]; author of Inner Life of Syria (1875, 1879), Arabia, Egypt, India [A Narrative of Travel] ([London & Belfasts: William Mullan & Son] 1879); devised method of Arabian Nights and deserves credit for financial success; constant efforts to further his career, regarding him as greatest Englishman of his time; devoted nurse in his last year; cottage in Mortlake; wrote biography; autobiography, ed. W. H. Wilkins in 1897, called Romance of Isabel Lady Burton; civil list pension; d. Baker St.; sole executor; burnt mss. of Scented Garden; destroyed his private diaries; permitted his trans. of Pentamerone and his verse rendering of Catullus (1894); commission memorial ed. of her husband’s better-known works; Life of Burton by Lady Burton, 2 vols. 1893; ed. version by Wilkins (1898). Note: Arabia, Egypt, India [A Narrative of Travel] ([London & Belfasts: William Mullan & Son] 1879) is available on Internet.org - online [accessed 16.09.2018].

Justin McCarthy, gen. ed., Irish Literature (Washington: Catholic Univ. of America 1904), gives extracts incl. ‘A Journey in Disguise,’ from Personal Narrative [to] El Medinah.

Peter Harrington Books (Cat. 2005) lists Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to El-Medinah and Meccah (London: Brown, Green & Longmans 1855-56), 1st edn., presentation copy; 3 vols.; contemp. half tan calf [£25,000].

[ top ]

Notes

Speke & Burton: In a ‘Tail’ to his What Led to the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1864), John Hanning Speke gave an account of his travels with Burton which includes the statement that Burton failed to pay the caravaneers used on the trip to Lake Tanganika - with further details about Burton’s contestation of Speke’s theory that Lake Victoria Nyanga was the source of the Nile - Burton, The Lake Regions of Central Africa (1860) - necessitating a second expedition on his part. The “Tail’ was excised from all but a dozen copies of Speke’s book on the publisher Blackwood’s advice, four of which are extant today. Speke had planned to include the suppressed material about Burton in a second edition, but died on 15 September 1864 in a shotgun accident, which is believed by some to have been suicide. (See Alison Flood as ‘Suppressed story of Richard Burton’s rival explorer surfaces’, in The Guardian (5 Sept. 2017) - available online [accessed 16.09.2018].

Note that the Wikipedia entry on Speke reports the final chapter of his life in these terms: ‘A debate was planned between Speke and Burton before the geographical section of the British Association in Bath on 16 September 1864, but Speke had died the previous afternoon from a self-inflicted gunshot wound while shooting at Neston Park in Wiltshire.’ The writer goes on to quote a contemporary report of the incident from The Times giving details of a fatal accident while out shooting with a friend and a game-keeper in attendance. In this account, his gun, left at the bottom of a stone way, discharged one barrel upwards into his chest destroying arteries at the heart. The writer concludes: ‘An inquest concluded that the death was accidental, a conclusion supported by his only biographer Tim Jeal,[8] though the idea of suicide has appealed to some.[17] Bearing in mind, however, that the fatal wound was just below Speke’s armpit, suicide seems most unlikely. Burton, however, could not set aside his own strong dislike of Speke and was vocal in spreading the idea of a suicide, claiming that Speke feared the debate.’

|

Proto-Dracula? Burton’s long canine teeth make him a candidate for consideration as a model of the title character in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (Barbara Belford, Bram Stoker, 1996, p.239 & ftn.) See also the following contribution by Victoria Hooper at Bookdrum > Dracula - online [accessed 01.10.2017]:

|

|

[ top ]

James Joyce: Joyce owned an Italian translation [of Arabian Nights] in Trieste and the Sir Richard Francis Burton 1919 edition in Paris. (Brandon Kershner, ‘Ulysses and the Orient: in “ReOrienting Joyce”’, JJQ Special Issue, Winter-Spring 1998, p.273; quoted in Brad Bannon, ‘Joyce Coleridge and the Eastern Aesthetic’, in JJQ, Spring 2011, p.500.)