Life

| 1890-1922. b. 16 Oct., at Woodfield, Clonakilty, Co. Cork; ed. Clonakilty National School; son of small farmer; went to London at 16 and worked there (1906-15) as PO clerk, later clerk with stockbrokers; educated self in evenings; treasurer of GAA club in London; joined IRB in London; fought in Dublin 1916 as Staff Captain and ADC to James Connolly in the GPO; wisely refused order to take down Tricolour on top of GPO under heavy fire but led first party out of GPO, with the O’Rahilly, before surrender; interned at Frongoch, N. Wales (Hut No.10) - being at first held at Stafford Jail with others; turned against the ‘military set-piece’ method of rebellion; became a member of IRB supreme council on his release December 1916; made oration at funeral of hungerstriker Thomas Ashe, 1917; minister of Home Affairs and later of Finance, in Dáil Eireann, 1919, organising the Republican Bonds that raised money for the counter-state [viz., National Loan]; adopted policy of confrontation with British authority in every context; director of organisation and intelligence for Volunteers; established intelligence service contacts inside Dublin Castle; |

| gained advantage when a cousin was transferred to London to decode cyphers; targeted inelligence collectors and organised liquidation of British agents known as Cairo Gang on 21 Nov. 1920 (“Bloody Sunday”), using an execution squad nicknamed the “Twelve Apostles” (poss. including Seán Lemass); subject of a Daily Express article named ‘The Bad Man of Ireland: Michael Collins and the Murder Gang’, 1920; organised some 160,000 members of Irish Volunteers during War of Independence; Sinn Féin candidate in Armagh, 1920, narrowly escaping threat of local clergy to oppose his selection; opposed Sinn Féin boycott of Northern Ireland; estimated that the IRA had little means to continue warfare after the disastrous burning of the Custom House, with 100 volunteers of the 2nd Dublin Battalion captured by Auxiliaries and 5 IRA killed in action, 24 June 1921; engaged to Kitty Kiernan, whom he met in a Co. Longford hotel - and with whom he exchange some 300 letters; set wedding date with Kitty, but thought to have conducted a love affair with Lady Lavery while in London at the Treaty negotiations; |

| purportedly said, after the Treaty signing: ‘I have signed my death warrant’; Collins negotiated end of hostilities with Andrew Cope, Under-secretary of State, in Dublin Castle; appt. delegate to London, and became a signatory of Anglo-Irish Treaty, Dec. 1921 - writing his misgivings to de Valera about his role [see infra]; justified the Treaty terms, falling short of the Republic, as ‘the highwater mark of what we can do in the way of economic and military resistance’ and ‘a stepping-stone, the freedom to achieve freedom’ adding: ‘the ideal is no good unless it lights our present path’; chairman of Provisional Govt.; commander in chief of Free State forces, covertly supported continuing IRA campaign in N. Ireland; met with Sir James Craig, effecting end of Sinn Féin boycott, Jan. 1922; second pact with Craig, 31 March 1922; entered election pact with Eamon de Valera, May 1922; |

| probably green-lighted the assassination of Field-Marshall Sir Henry Wilson, wartime Chief of Staff who assumed a new post as adviser to the Ulster Unionists, 22 June 1922 [resulting in the hanging of the two accomplices Joseph O’Sullivan and Reginald Dunne] - triggering British demands that the anti-Treaty HQ in the Four Courts be attacked and thereby leading to the opening of the Irish Civil War; caught in a republican ambush led by Liam Deasy at Béal na mBláth, Co. Cork, and received a gunshot wound in the head, apparently from a bullet that ricochetted off the tarmacadam, having stepped out from the armoured car; d. the following day, 22 Aug., shortly after 8.30 a.m. [aetat 31]; bur. Glasnevin; bronze bust by Albert Power; P. S. O’Hegarty prepared a bibliography in 1937; Collins is also the subject of striking elegy by Denis Devlin (in which the phrase ‘Murderous angels in his head’), and an internationally successful film by Neil Jordan (Michael Collins, 1996), imputed responsibility for the assassination of Collins ot de Valera; Collins received lucrative offers for an autobiography; there are reputedly 200 biographies to date; his uniform is displayed in the national Museum of Ireland at Collins Barracks; his Webley revolver and holster, recovered at the scene of his death, were sold in auction for €50,000 [reserve] in March 2009. DIB ODNB DIH OCIL FDA |

[ See Michael Collins Society website online; accessed 01.05.2017. ]

[ top ]

Works

|

See also Michael Collins: His Own Story, told by Hayden Talbot (London: Hutchinson & Co. [1923]); Do. [2nd edn.] with a preface by Eamon de Burca (Dublin: De Burca 2012), xii, 203pp. ill. [24 unnum. pp. of b&w pls.; 25 cm; a ghost-written work regarded by some as tantamount to forgery; available at Collins website - online; see also contemporary review of 11 May 1923 in the Spectator Archive - online.] |

[ top ]

Criticism

|

| Fiction & Drama |

|

| Second opinion |

|

[ top ]

Commentary

Erskine Childers: Erskine Childers wrote an obituary for Collins in An Phoblacht (Sept. 1922): ‘For [no one] will be ungenerous enough to doubt that his ruling motive … was that the Treaty was a necessary halting place on the road to a recognised republic, that it gave us freedom to achieve freedom …’ (Cited in Eamonn Phoenix, review of Costello, Michael Collins in his Own Words, in Fortnight, July-Aug. 1997, p.35.)

Oliver St John Gogarty, I Follow St. Patrick (1938): ‘To anyone who has been through the late war in Ireland it will be apparent that it requires but slight organisation to enable a man who is on the run to hide, provided that there exists a sympathy for his condition and ideals which is widespread enough to further his movements. Collins walked, by virtue of this sympathy, under the noses of that unconstitutional and irregular force of gunmen which received the name of “Black and Tans”. He walked through the principal streets in broad daylight.’ (p.107.)

Further: ‘The quickest intellect and nerve that Ireland bred’ ‘For such a big man, he moved with the natural grace of a ballet dancer’. (Quoted on Michael Collins Society website - online; accessed 01.05.2017.)

Winston Churchill: ‘He was an Irish patriot, true and fearless ... When in future times the Irish Free State is not only prosperous and happy, but an active and annealing force ... regard will be paid by widening circles to his life and to his death ...’ (Quoted on Michael Collins Society website - online; accessed 01.05.2017.)

Elizabeth Burke [Countess Fingall], Seventy Years Young, with Pamela Hinkson (1937; Dublin: Lilliput 1991), remarks that ‘Michael Collins was what he looked - a big simple Irishman - and remained so.’ Note further, When Hazel Lavery’s dog pawed Lord Birkenhead’s feet under the table, the latter remarked, ‘I’m sorry, I thought you were making advances.’ Michael Collins sprang up:‘D’ye mean to insult her?’ Hazel explained, ‘Lord Birkenhead was only making a joke’, to which Collins: ‘I don’t understand such jokes!’ (p.403; and see ditto in Books Ireland, March 2007, p.46).

[ top ]

Eoin Neeson, The Civil War (1966, rep. 1989), ‘It should be borne in mind that, according to PS O’Hegarty and others, Churchill was one of those who had given the guarantee to Collins that he (Churchill) would see to it that the Northern would consist of only four counties which could not survive as an economic unit.’ (p.21.) Neeson quotes Collins on signing the Treaty: ‘“I signed it because I would not be one of those who commit the people to war without the Irish people committing themselves to war. They had the freedom to advance towards independence and a Gaelic state”, he said.’ (p.75.) [This title cited in F. S. L. Lyons, 1971, as Cork 1967; pb. ed. 1969].

Joseph Lee, Modernisation of Ireland, 1850-1918 (Dublin 1973), ‘Michael Collins death the only public tragedy of the Civil War. According to Lee, he professed to want a country distinguished by social equality, economic efficiency, cultural achievement, and religious tolerance. “We must not have the destitution of poverty at one end and at the other an excess of riches in possession of a few individuals.” He scoffed at de Valera’s belief that the people must be kept poor to nurture their idealism, and retorted, “In the ancient days of Gaelic civilisation the people were prosperous and they were not materialists. They were one of the most spiritual and intellectual people in Europe ... We want such widely diffused prosperity that the Irish people will not be cursed by destitution into living practically “the lives of the beasts”.’ (Last speech, Michael Collins, The Path to Freedom [1922], Cork 1968, p.108, 106; Lee, op. cit., p. 64.)

| Sir Shane Leslie: Poem on the Death of Michael Collins | ||

| ‘What is that curling flower of wonder As white as snow, as red as blood? When death goes by in flame and thunder And rips the beauty from the bud. ‘They left his blossom, white and slender Beneath Glasnevin’s shaking sod; |

His spirit passed like sunset splendour Unto the dead Fiannas’ God. ‘Good luck be with you, Michael Collins, Or stay or go you far away; Or stay you with the folk of fairy, Or come with ghosts another day.’ | |

| Rep. on Sara’s Michael Collins page [link]; accessed 12.06.2006. | ||

[ top ]

Ruth Dudley Edwards, review of James Mackay, Michael Collins: A Life (Mainstream), in Times Literary Supplement (27 Sept. 1996, p.7): ‘Collins characterised as anti-democratic with a taste for violence; Mackay, a Scots Presbyterian with a taste for romantic heroes indicated by previous books on William Wallace and Robert Service, depicts him as sweeping aside “blimpish” British dinosaurs and self-serving constitutional politicians in the IPP [Irish Parliamentary Party], and sees de Valera as “a political pygmy, a poisoned dwarf who had no compunction about sacrificing his country on the altar of his own pigheadedness”, while holding that the civil war was his doing; Edwards notes that Mackay is a “sexual puritan” who denies the authenticity of the Casement diaries and discredits tales of Collins as a “hard-drinking, womanising, image” as “got up to assassinate his character”; Edwards considers that the author ‘shows a complete failure to understand the Irish’, and reflects on the folkloric fame of Dan O’Connell.

Enda Staunton, ‘Reassessing Michael Collins’s Northern Policy’, in Irish Studies Review, 20 (Autumn 1997), p.9-16; claims that evidence of his acceptance of the limitations of the Treaty in terms of cessation of anti-Partition militancy has lain in archives for decades; ‘Collins approach displays features of moderation from the start which eventuated in an approach to Unionists and Home Rulers in Belfast less than a month before his death’; ‘concentrating on the periods Feb.-March and April-May 1922, when this policy had broken down and Collins reverted to militarism, [created] an unbalanced picture’ (p.9).

J. C. Kelly-Rogers, ‘Aviation in Ireland - 1784 to 1922’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 2 (Summer 1971), pp.3-17: Irish Army Air Corps had only one non-military aircraft, a 5-seater Martinsyde A2 fitted with a Rolls-Royce Falcon III engine; purchased by Comm.-Gen. McSweeney and Capt. Charles Russell, former members of the IRA (during Anglo-Irish Truce) by reason that ‘one of the Irish delegation attending the treaty talks in London was General Michael Collins on whose head the British Government had earlier placed a reward of £10,000.’ Further, ‘If the talks broke down Collins might become a fugitive and it was to facilitate his escape to Ireland that this aircraft, nick-named “The Big Fella”, was acquired. [..] A photograph shows the new Irish tricolor being painted on the fuselage - the first aircraft to carry these markings.’ (p.16.)

J. J. Lee: ‘But sharp differences exist concerning the quality of his [Collins’s] political judgement, above all during the Treaty negotiations and the post-Treaty period. Should he have gone to London at all, or like Cathal Brugha and Austin Stack, refused the poisoned chalice - or at least refused unless De Valera supped from it as well? Was he first out-maneuvered by De Valera in Dublin, and then by Lloyd George in London? Was he a novice in the hands of these allegedly more astute operators? Was he right to sign the Treaty? Did he subsequently, as Chairman of the Provisional Government, “try to do too much” to avoid the Civil War, in contrast to De Valera’s “too little”, in the lapidary formation of Desmond Williams?’ (‘The Challenge of a Collins Biography’, Michael Collins and the Making of the Irish State, 1998; quoted in Sara’s Michael Collins page [link]; accessed 13/07/2006.)

Stephen Collins [political ed.], ‘Who shot Collins?’, in The Irish Times (21 Aug. 2010), Weekend Review, p.4: ‘[...] The most obvious and plausible explanation is that Collins was killed by a bullet fired by one of the six members of the republican ambush unit at Beal na mBláth. One of them, Sonny O’Neill, a former British army marksman, believed that he had hit a tall Free State officer. The evidence suggests that he had indeed shot Michael Collins. O’Neill was using dumdum bullets, which disintegrate on impact, and this would explain the gaping wound in Collins’s skull. Liam Deasy, who was in command of the ambush party, reportedly said: “We all knew it was Sonny O’Neill’s bullet.” O’Neill died in 1950.’

[ top ]

Quotations

The Path to Freedom (1922): ‘It is only in the remote corners of Ireland in the South and West and North West that any trace of the old Irish civilisation is met with now. To those places the social side of Anglicisation was never able very easily to penetrate. Today it is only in those places that any native beauty and grace in Irish life survive ...’ (Quoted in Anthony Cronin, No Laughing Matter: The Life and Times of Flann O’Brien, 1989, p.137.)

The Path to Freedom (1922): ‘We only succeeded after we had begun to get back our Irish ways ... after we had made a serious effort to speak our own language, after we had striven again to govern ourselves.’ (rep. edn. 1968, p.100.)

Further: ‘The biggest task will be the restoration of the language.’ (op. cit., p.102; both of the foregoing quoted in Declan Kiberd, ‘Irish Literature and History’, appended to Illustrated History of Ireland, by Roy Foster (OUP 1989), p.275; also given in Inventing Ireland, 1995, p.154; and Brian Ó Cuív, ‘Irish Language and Literature, 1845-1921’, in A New History of Ireland, Vol. VI: Ireland under the Union, II: 1870-1921, ed. W. E. Vaughan, pp.385-35, p.414 [adding last sentence].)

[ top ]

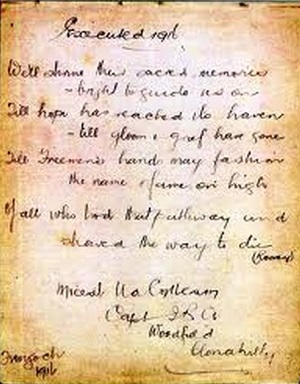

| Note: While in Frongoch Internment Camp, Collins appears to have written a poem to the 1916 leaders who had been executed in Dublin. | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||

The single-page manuscript ends with a parenthetical word - possibly ‘Rooney’, which may signify William Rooney (q.v.; obiit. 1901), the friend of Arthur Griffith whom James Joyce had famously disparaged for excessively patriotic verse in a review of his (Rooney’s) poems edited by the other in 1902. If so, this can be read as an attribution suggesting that Collins recalled or copied the verses, turning them from their original purposes to a commemoration of the 1916 leaders. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

[ top ]

Irish civilisation: ‘I stand for an Irish civilisation based on the people and embodying and maintaining the things - their habits, ways of thought, customs - that make them different - the sort of life I was brought up in [...; see note] Once, years ago, a crowd of us were going along the Shepherds Bush Road when out of a lane came a chap with a donkey-just the sort of donkey and just the sort of cart that they have at home. He came out quite suddenly and abruptly and we all cheered him. Nobody who has not been an exile will understand me, but I stand for that.’ (Quoted in Frank O’Connor, The Big Fellow, 1965, p.20, citing P. S. O’Hegarty; also quoted in Peter Costello, The Heart Grown Brutal, 1977, p.188; D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland, London: Routledge 1982; 1991 Edn., p.351 [citing Costello, as supra.])

Note: ‘I stand for [.... &c.]’ - the sentence is quoted as a epigraph [inter al.] in Francis Shaw, ‘The Canon of Irish History: A Challenge’, in Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, LXI, 242 (Dublin 1972), pp.116 - citing P. S. O’Hegarty, The Victory of Sinn Féin, 1924, p.139.

[ top ]

Gaelic League: ‘Irish history will recognise in the birth of the Gaelic League in 1893 the most important event of the nineteenth century. I may go further and say, not only the nineteenth century, but in the whole history of the nation. It checked the peaceful penetration and once and for all turned the minds of the Irish people back to their own country. It did more than any other movement to restore the national pride, honour and self-respect. Through the medium of the language it linked the people with the past and led them to look to a future which would be a noble continuation of it.’ (Quoted by Philip O’Leary in review of Proinsias Mac Aonghusa, Ar Son na Gaeilge, Conradh na Gaeilge 1893-1993 [Stair Seanchais] (Conradh na Gaeilge 1993), and other Irish works, in Irish Literary Supplement, Fall 1994.]

On the 1916 Proclamation: ‘I do not think the Rising week was an appropriate time for the issue of memoranda couched in poetic phrases, no[r] of actions worked out in a similar fashion.’ (See Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins, pp.53-54; quoted in Declan Kiberd, Inventing Ireland, 1996, p.207.)

May 1919: ‘The position is intolerable[,] the policy now seems to be to squeeze out any one who is tainted with strong fighting ideas or I should say I suppose ideas of the utility of fighting’; ‘official Sinn Féin is inclined to be ever less militant and every more political and theoretical.’ (; quoted in Margery Forester, Michael Collins: The Lost Leader, 1971; cited in D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland, 1991 Edn., p.321.) Further, denouncing the north east of Ulster for having, ‘lost all its native distinctiveness. It has become merely an inferior Lancashire. Who would visit Belfast or Lisburn or Lurgan to see the Irish people at home?’ (The Path of Freedom [q.edn.], p.123; Boyce, op. cit., 1991 Edn., p.352.)

The Treaty (1): ‘The Treaty was signed by me not because they [British Govt.] held up the alternative of immediate war. I signed it because I would not be one of those to commit the Irish people to war without the Irish people committing themselves to war [...] I can state for you a principle of government which everybody will understand, the principle of government by the consent of the governed.’ (Quoted in Stephen Collins [political ed.], ‘Sharing Collins’s legacy of democracy’, in The Irish Times, 21 Aug. 2010; Weekend Review, p.4.)

The Treaty (2): ‘I do not recommend it for more than it is. Equally, I do not recommend it for less than it is. In my opinion, it gives us freedom, not the ultimate freedom that all nations desire and develop to, but the freedom to achieve it.’ (19 Dec. 1921; in Dáil Éireann, Official Report, Debates on the Treaty, Dublin 1922, vol. 458, cols. 1414-15. (Quoted [in part] in Chubb, The Politics of the Irish Constitution, 1991, p.14.)

Survival of the fittest: An essay on ancient and modern warfare written by Collins in 1904 was auctioned by Adam’s/Mealy’s in Easter Week, 2006 (estimated value, €30-40,000). The essay was written at school in Clonakilty, aged 14, and presented by his sister Kathleen to a primary school teacher who had asked for a memento. Reflecting that the art of war was as old as human history, it includes the sentence: ‘it would seem as if nature aided and abetted this feud [sic] for the attainment of her inexorable ideal, “the survival of the fittest”. (Irish Times, 4 Feb. 2006).

[ top ]

References

Dictionary of National Biography styles Michael Collins an ‘Irish revolutionary leader and chairman of provisional government of Irish Free State in 1922; killed by Irregulars in Béal na mBláth; bur. Glasnevin.

COPAC lists Michael Collins [script] - Geffen Pictures presents a Neil Jordan film; a Stephen Woolley production; music by Elliot Goldenthal; editors, J. Patrick Duffner and Tony Lawson; production designer, Anthony Pratt; director of photography, Chris Menges; co-producer, Redmond Morris; producer, Stephen Woolley; directed and written by Neil Jordan (1998)[ top ]

Hyland Catalogue (214) lists Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins: Commemoration Booklet (1922), contribs. by Padraic Colum, Gogarty, Oliver St. John [Sean] Ó Conaire, Sir Shane Leslie, et al. Hyland Catalogue (220, 1995) lists Michael Collins, Saorstat [A Memorial Number], 30 Aug. 1922 [2nd. edn.]

De Burca Catalogue, 44 (1997) lists The Path to Freedom, with port. frontis. Dublin, Talbot, 1922 [sic]., 153pp.

Library of Herbert Bell, Belfast holds [Hayden Talbot], Michael Collins, His Own Story Told to Hayden Talbot (London n.d.).

[ top ]

Notes

Sebastian Barry: Barry’s Boss Grady’s Boys contains a character called Mick Collins who recalls his namesake calling for another Ireland in which ‘we could be men in our own country’; note also the central character’s hard-won admiration for Collins in Barry’s Steward of Christendom (1995), and Collins’ incidental role in Barry’s The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty (1998), where Teasy [Teresa] prays for him a ‘whole fortnight’ to the infuriation of the title-character, her brother.

Tom McIntyre, Good Evening, Mr Collins, in Frank McGuinness, ed., The Dazzling Dark: New Irish Plays (1996); an Afterword accredits Beaslaí’s two-volume life of Collins, the end of which ‘left me [McIntyre] quivering’, with the inspiration for his own play; McIntyre goes on to discuss ‘the connection between the Don Juan exploits and his legendary deeds as the leader of the armed struggle to expel the British’ [p.231-35] Note also that Alvin Jackson calls Collins ‘the bluff manufacturer of terror’, in his life of Col. Edward Saunderson [Irish Studies Review, 20, Autumn 1997.]

A. T. Q. Stewart, ed., Michael Collins: The Secret File [with HM Public Records Office] (Belfast: Blackstaff 1998), is disparaged as ‘manufactured’ by reviewer Pádraig Ó Snódaigh, in Books Ireland (Nov. 1998), p.310.

Peter Costello, The Heart Grown Brutal (1977), p.209: Sir John Lavery, who painting Collins lying in state, thought he ‘might have been Napoleon in marble as he lay in his uniform covered by the Free State flag with a crucifix on his breast.’ (Source uncited).

[ top ]

Collins & Film (I): Michael Collins was the subject of a Hollywood film, Beloved Enemy, Sam Goldwyn prod. 1936); also This Other Eden (1959), dir. by Emmet Dalton and premiered at the Cork Film Festival; Collins was later personified by Brendan Gleeson in The Treaty (1991, RTE & Thames TV); a hagiographical account was given by Kenneth Griffith in Hang Up Your Brightest Colours (ITV 1973), commissioned by Lew Grade, but not shown until 1994; Griffith successfully sued ITV, and spent the proceeds turning his home into a Collins shrine. (See Vincent Browne, Film West, 1996, comment on Michael Collins, dir. Neil Jordan, 1996, p.22.)

Collins & Film (II): Michael Collins / Geffen Pictures presents a Neil Jordan film ; a Stephen Woolley production ; music by Elliot Goldenthal ; editors, J. Patrick Duffner and Tony Lawson ; production designer, Anthony Pratt ; director of photography, Chris Menges ; co-producer, Redmond Morris ; producer, Stephen Woolley ; directed and written by Neil Jordan (1997).

Sam Maguire, a Protestant from Cork, recruited Michael Collins to the IRB and swore him in, in the London PO; Maguire (1879-1927) later acted as an agent for Collins in London.

Over the Moon?: Among the many who share a name with the Irish revolutionary is a crew member of the first space-flight to land on the moon, viz., Michael Collins in company with the better-known Neil Armstrong and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr.

Women at war: Those treated as active in the nationalist cause in Meda Ryan, Michael Collins and the Women Who Spied for Ireland (Mercier 2006), incl. Moya Llewelyn Davies, Eileen McGrane, Susan Killeen, Dilly Dicker, Madge Hales, Sinéad Mason, Lily Mernin, Siobhán Creedon, Josephine Mountmarch, Patricia Hoey, Dr Brigid Lyons, and Nora Wallace - who kept a police cypher key for Collins. (See Books Ireland, March 2007, p.45.)

[ top ]

Longford: At one point Collins was charged in Longford Courthouse [Sessions] with making inflammatory speeches - as was Thomas Ashe (See James McNerney, in Longford Teatbha 40th Anniversary Edition, reviewed in The Irish Times, (6 Sept. 2008). Note that it was in a Longford hotel that Collins met Kitty Kieran.

Enniskillen: ‘I must tell you my story about Michael Collins. About 20 years ago, I visited Enniskillen to do a story for the Sunday Times of London. There I met these two wonderful old ladies who had been concert pianists for many years, playing as a duo. Anyway, they told me that sometime after 1916 Collins was spotted in the town. Apparently he was seeing some girl there at the time. The word got out that the Big Fellow was about the place, but nobody, in a predominantly Protestant and Unionist town, reported him to the RIC. I asked one of the ladies why they hadn’t turned him in. “Oh,” she replied. “But he was a gentleman, and it wasn’t for us to interfere with his private life.”’ (Posted by Watchman on Irishcentral opinion [online; 29.10.2010.

Killed in action - Niall Meehan writes to The Irish Times (25 Aug. 2012): ‘Taoiseach Enda Kenny has been criticised for referring to Michael Collins being shot dead on August 22nd, 1922 as an “assassination”. In his 1984 Collins commemoration oration, then Fine Gael minister for justice Michael Noonan referred to it as “murder”, prompting former anti-Treaty republican and senior civil-servant, Todd Andrews, to respond, “Michael Collins was not murdered. He was killed in action” (Letters, August 29th, 1984).’

Murder Most Foul: At the fund-raising event in the Sheraton Hotel, Manhattan (NY), Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams berated the press treatment of the IRA and his own role in relation to the rape denunciation of Mairia Cahill and stated: ‘Mick Collins#146; response to the Independent’s criticism of the fight for freedom was to dispatch volunteers to the Independent’ls offices. They held the editor at gunpoint and then dismantled and destroyed the entire printing machinery! Now I'm obviously not advocating that...’

[Blog-version: ‘And when the Irish Independent condemned his actions as “murder most foul” what did Michael Collins do? He dispatched his men to the office of the Independent and held the editor at gunpoint as they dismantled the entire printing machinery and destroyed it.’]

The remark - which he repeated on his blogsite - occasioned objections from the Tanaiste Joan Burton who adverted to the death of journalists such as eronica Guerin and Martin O’Hagan and construed it as an attack on the freedom of the press in Ireland. (See Irish Independent, 13 Nov. 2014 - online; and Irish Independent, 9.11.2014 - online.)

[ top ]