Life

1770-1837 [known as “Watty”; pseud. “Julius Pubicola”]; b. Westmeath; son of blacksmith who was later rounded up on suspicion of Defenderism by Lord Carhampton; apprenticed to Benjamin Powell and another gunsmith; ed. by Bryan McGarry (“Philomath”); supplied small-arms to Ordnance in Dublin Castle; secretly edited the broadsheet Union Star, printed in Little Ship St., 1797, in which he attacked the Orange Order and also editors of other journals such as Higgins (Freeman) and Gifford (Warder); joined United Irishmen, and reputed body-guard of Lord Fitzgerald, but proposed more radical tactics including the assassination of loyalists; contract with government terminated at act of Union, going to English manufactury suppliers instead; claimed govt. reward for naming the editor of Union Star (himself); accepted pension of £100 from Under-Secretary of State, Edward Cooke, with a promise of £400 on reaching America on condition that he stayed out of Ireland; thought to have worked as a tally-merchant [i.e., candles] during his nine-month stay before returning to Europe, first at Paris and then at Ireland; |

||

| issued Advice to Emigrants (1802), praising Thomas Jefferson; published and edited The Irish Magazine or Asylum of Neglected Biography (Nov. 1807-Dec 1815), a nationalist journal in the spirit of the United Irishmen - always with at least one plate - in which he criticised the government and carrying on a journalistic feud with John Brenan (ed. of Milesian Magazine), who denounced him in turn as an informer - given his receipt of a salary; also carried specimens of Irish writers such as Fearflatha O’Gnimh and translations by Thomas Dermody on its pages, as well as an articles on Turlough Carolan [q.v.] Oliver Plunket, Patrick Sarsfield, Lord Edward, and Robert Emmet; journal seized in Oct. 1809 for non-payment of stamp-duty; gave account of ‘Massacre of Carlow’ in 1798 (Dec. iss., 1809); open letter to Sir Jonah Barrington (July 1810); prosecuted for seditious libel on account of ‘The Painter Cut: A Vision’ (July 1810), authored by Thomas Finn (”Orellana”); | ||

|

||

defended by Daniel O’Connell [acc. Cox. himself] and sentenced by Lord Newbury - later satirised as Judge Bladderchops - to the public stocks on 9 March 1811, to be followed by a year in Newgate Gaol, which was extended to three on account of the continued appearance of the offending journal (The Irish Magazine) which he continued to edit from prison; following the death of his first wife - known only to have been a Methodist - he married the widow of Benjamin Powell, 1797; a young son and namesake died, aged 12, during Cox’s term in prison, in 1814; in April 1812 he was depicted murdering his [first] wife in Brenan’s Milesian Magazine; |

||

| agreed to close the Irish Magazine - which enjoyed prodigious sales - set up a newspaper called The Exile in New York (2 vols.; Jan. 1818-March 1819); moved to Paris and returned to Ireland, apparently bankrupt, 1802; sought position as Dublin librarian; later wrote plays, including an attack on Dan O’Connell, The Cuckoo Calendar (Dublin 1833); his farce The Widow Dempsey’s Funeral (1822) was revived in an abridged version by J. Crawford Neil for Theatre of Ireland, Dec. 1911; accused by Brenan of revealing whereabouts of Lord Edward to the Castle but exonerated by W. J. Fitzpatrick (Lord Edward Fitzgerald and his Betrayers, 1869); spent over three years in prison on libel and sedition charges at different times; twice married; d. 17 Jan., at 11 ODNB PI DIW DIH MKA RAF OCIL. | ||

[ What a Cox!! - editorial note]: The chronological facts of Cox’s life and career are extremely confused and variable as given in various reference works. Chiefly, the confusion concerns the period of his visit to American under fiscal terms struck with Under-Sec. Edward Cooke, who supplied a pension of £100 and a bonus of £400 on arrival there. In one version, this transaction and the ensuing journey took place within a year of the foundation and closure of his broadsheet Union Star - i.e., 1797 - and involved his acting as an informant against the United Irishmen prior to the Rebellion of 1798. In another, his American sojourn did not take place until 1816, following the closure of the Irish Magazine to which it was linked in principle.

Some clue as to the truth is provided by the date of his little book Advice to Emigrants, dated 1802 and said in the title to be based on ‘observations made during a nine months residence in the middle states of the American Union’. This does not specify the date of his arrival or departure but it does place both long before his publication of the Irish Magazine - meaning that he returned to Ireland and, for reasons unknown, escaped punishment for his broken promise. (The Treaty of Amiens in 1802 is sometimes given as the immediate reason for his return - being the short-liived peace between England and its allies, on one side, and France on the other. For that moment, at least, all thought of Republican insurrection was off. By contrast, in point of time, his later ‘letters’ addressed to Bishop Connolly of New York are dated 1819-1820 - and ditto The Snuff-Box (1820), a diatribe against American customs and institutions said on the title page to have been printed in ‘New-York’. Connolly, to whom the polemical letters are addressed, was an Irish priest of Irish birth who was appointed to the American see while in Rome in 1814, travelled to America via Ireland (where he attempted to recruit priests), and arrived at New York after a difficult sea-voyage in November 1815. He was reputed to be mild and kindly in disposition and said to have filled his hours with visits to his flock of mostly poor Irish immigrants distributed throughout four nominal parishes and facing aggression from ‘native’ Americans (i.e., Anglophone Protestants).

While it is said in the Dictionary of National Biography [UK] that he died in prison both D. J. O’Donghue in Poets of Ireland (1912) and C. J. Woods in the Dictionary of Irish Biography (RIA 2004) are agreed that he died in a private lodging at 12 Clarence St., Dublin, in 1837 - a year or so after the removal (or forfeiture) of his government pension ‘for whatever reason’, ad the DIB puts it. The RIA Dictionary puts the date of this change in fortune at 1835 whereas O’Donoghue places it in 1836 perhaps hinting that hardship was the immediate cause to his demise. What the pension was for, or why it was discontinued at the said date are not known. Was it a continuation of the original contract for £100 p.a. in return for information, or was it a new arrangement covering the new ground? Surely the original would have been terminated when he breached the terms by his very return in 1800 or so? Especially if, as said somewhere, he carried a gun or supplied blunderbusses to the rebels in Emmet’s Rising and was arrested in flagrante at Smithfield on that fateful day in 1803?

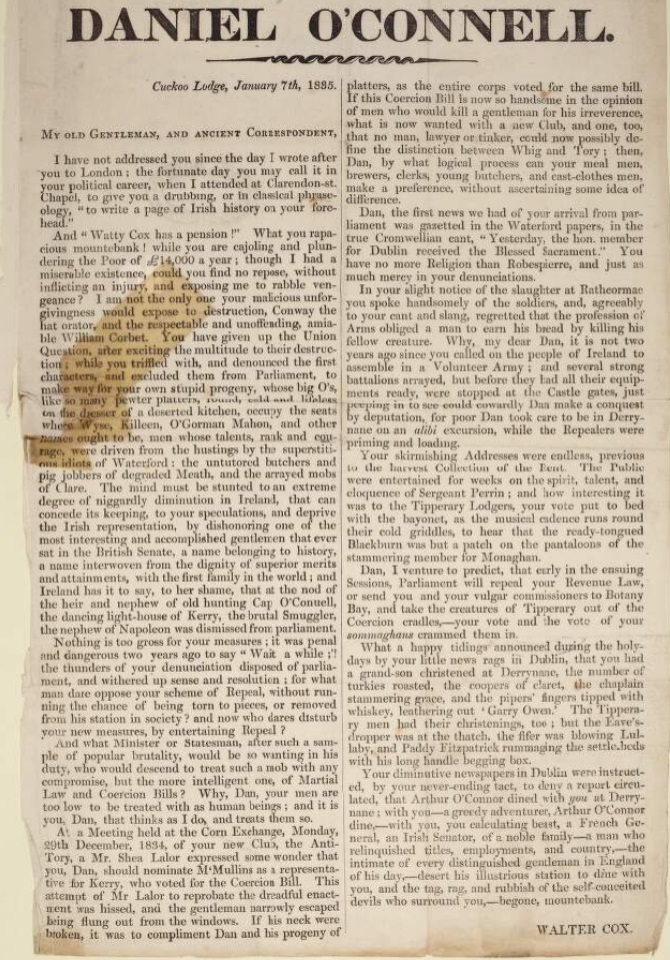

All of this suggests a life-long history of double dealing with the revolutionaries and the government to match that of Francis Higgins, the notirous "Sham Squire" who revealed the whereabouts of the United Irish leaders in 1798 - though O’Donoghue asserts that he was cleared of that particular offence by W. J. Fitzpatrick who revealed the role of Higgins in the whole disasterous affair. It is hardly in doubt that Cox did play cat and mouse with the secret service in the Castle but possibly considered himself an honurable nationalist. John Brennan called him an government agent which he virulently denied but there is a and further clue in a surviving broadsheet which takes the the form of a letter to Daniel O’Connell - the “Great Mendicant” in Cox’s satirical parlance. In it he gives a vituperative response answer to O’Connell’s having apparently said ‘And Watty Cox has a pension!’ on some occasion - possibly in Parliament where his name was a least once mentioned by Robert Peel - with a rejoinder about the £14,000 that O’Connell has ‘plundered’ from the Irish poor in just one year to fund his Repeal movment and, by implication, his well-fed self. Cox goes on: ‘Though i had a miserable existence, could you find no repose, without inflicting an injury, and exposing me to the rabble vengeance?’ This surely raises the likelihood that O’Connell’s intervention had the effect of bringing an end to Cox’s economic mainstay in the year in question. (An image of broadside in superlative NLI catalogue is copied on this page below - and the reader must surely share with me a sense of awe at this new way of doing literary research.)

While known fact of Cox’s hostility to British rule in Ireland, his connivance with the government for personal safety and gain, his early and later visits to America and his publishing history are all well-known. Yet the manner of speaking about his return to America reveals a persistent uncertainly about his financial means. Was this the occasion on which he accepted the bribe to stop publishing and pocketted £400 along with a £100 pension? The RIA Dictionary says, a little coyly, that he founded and edited the Exile in New York during 1817-18, ‘after he landed in America again’ [my italics]) - calling it a journal "similar in character to Irish Magazine’ [online]. But this "again" is not enough to tell us why he ceased to publish his hugely successful Irish Magazine and how he funded his transatlantic passage or found the means to launch a similar paper - albeit unsuccessful - in the chief city of the former colony and new republic of the United States? It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that his treaty with the Under-Secretary occurred at this date rather than the earlier one of 1797.

D. J. O’Donoghue likewise says that Cox when to America again in 1816 - and this may be where C. J. Woods gleaned his own elusive phrase. Which of these, or both, was funded by the government in the shape of a pension and a bonus is not made clear on any side. It is tempting to supposed that his Advice to Emigrants, written in the spirit of a disgruntled returnee after ‘nine months [in the] middle states of the American Union’ (Massechussets?) was not published in 1802, as shown in the NLI Catalogue [online] and World Catalogue (though not in the British COPAC system - online)- was actually printed in 1820 - yet the repeated detail that he was a tallow-merchant in Baltimore in 1801 tells against this. It also makes it difficult to tally with his editorship of the Union Star but easier to connect with the mop-up operations around the 1798 Rebellion in which he played an ambiguous, if low-key, part.

The rumour that he was arrested in 1803 can only be true if he did return to Ireland in 1802, thus sacrificing his pension agreement - yet this seems more likely to be associated with the suspension of the Irish Magazine in 1815-16. The mystery of Watty Cox’s biography does nothing other than thicken the longer one explores it. His character is another matter. While the biographical questions raised here remain chronically unresolved, the Dictionary article by C. J. Woods remains in every way the most measured appraisal of his position in the contemporary cultural and political landscape. BS / June 2024.]

[ top ]

Works| Journals (editorial) |

|

| Original works (poetry & drama) |

|

| Pamphlets & tracts (Irish) |

|

| Americana |

|

| Illustrations (plates) |

|

| Posthumous |

|

| Reprints |

|

|

Criticism

|

|

[ top ]

Commentary

Thomas Furlong, ‘Sketch of Mr. Walter Cox’, New Irish Magazine and National Advocate (1822): ‘[H]e had few redeeming qualities, and these few, in the end, were perverted to the satisfaction of private pique. With a strong mind and boldness of expression he arrested the attention of the public, but never instructed, for his success arose from his intimate knowledge of the characters of his contemporaries which he drew with the fearlessness of Hogarth. Protracted essays or finished articles were beyond the abilities of Cox, for although a periodical writer for more than seven years he ever produced anything worth transcribing.’ (Quoted by Sean Mythen, “Thomas Furlong”, PhD. Diss., UU 1997.)

R. R. Madden (United Irishmen), ‘Had he received a liberal education, and been early taught to feel the restraints of religion, in all probability he would have been a vigorous, fearless, and faithful advocate of justice, a useful and influential member of society, a person of strong intellectual powers, and one who might have loved his country with the tempered ardour of a Christian patriot. Trained as he was and uncompensated by religious impressions for the want of mental culture, few men of his time, and of his rank and station, rendered themselves more feared and less loved than Walter Cox.’ (Cited in Sean Mythen, ‘Thomas Furlong’ [thesis], Chap. 1; UUC, 1999]. Note, Madden reports that Cox was publically denounced by Brenan in his Milesian Magazine as the betrayer of Lord Edward though the real recipient of money was Francis Higgins [also suspected was Samuel Neilson]; does not mention Cox’s attacks on Daniel O’Connell.

Brian Inglis (Freedom of the Press in Ireland (1954), reports that Cox ‘urged upon [Edward] Cooke the desirability of publishing everything that was known about the [united Irishmen] movement, because, he said, the United Irishmen would be deterred from taking any rash step if they realised how comprehensively they had been betrayed.’ , p.91, quoting Cooke to Whithall, 13 March 1798 [P.R.O, H.O., 100/80]; cited by Sean Mythen; thesis on Thomas Furlong, UUC 1999.)

W. J. McCormack refers to Cox’s Magazine in a ftn. to his edn. of Maria Edgeworth’s The Absentee (OP 1988); the issue of Nov.1807 that interests him opens with a brief sketch of the life of Carolan, and a front. port. of John Colclough, ‘that much lamented United Irishman’; sketch refers explicitly to “Grace Nugent” and “Mrs Crofton” among Carolan’s songs; the sketch was reprinted in the issue of oct. 1809. (Intro., The Absentee, 1988, p.xxiii.)

Conor Cruise O’Brien, The Great Melody (1992), regarding the rumour that Rev. Thomas Hussey was called to the death-bed of Edmund Burke, Patrick J. Corish, consulted by O’Brien, remarks that the Irish Magazine (1808) contains a letter stated to be from ‘one of the Maynooth Professors’ and claiming that Hussey ‘attended Burke spiritually in his last illness’. Corish adds, there is a touch of Private Eye about the Magazine, but Private Eye has been known to get it right!

Quotations

Un-Irish behaviour: Cox aspersed the Catholic bishops’ stance on the Defenders and United Irishmen as sending ‘a man to the devil for loving his country’ (Irish Magazine, March 1815; quoted in Dáire Keogh, ‘ Catholic responses to the Act of Union’, in Acts of Union: The Causes, Contexts and Consequences of the Act of Union, ed. Keogh & Kevin Whelan, Dublin: Four Courts Press 2001, p.160.)

| Watty Cox, ‘Letter to Daniel O’Connell’, 7 Jan. 1835. |

| Cuckoo Lodge, January 7th, 1835 |

| My old Gentleman, and ancient Correspondent, ... |

|

|

In your slight notice of the massacre of Rathcormac you spoke handsomely of the soldiers, and agreeably to your cant and slang, regretted that the profession of Arms obliged a man to earn his bread by killing a fellow creature. Why, Dan, it is not two years since you called on the people of Ireland to form a Volunteer Army ... Your diminutive newspapers in Dublin were instructed, by your never-ending tact, to deny a report circulated, that Artur O’Connor dined with you at Derrynane; with you, a greedy adventurer, Arthur O’Connor dine, - with you, you calculating beast, a French General, an Irish Senator, of a noble family - a man who relinquished titles, employments, and country - the intimate of every distinguished gentleman in England of his day, - desert his illustrious station to dine with you, and the tag, rag, and rubbish of the self-conceited devils who surround you, - begone, mountebank.

|

| Source: National Library of Ireland - click to enlarge or see more legible copy online. |

[ top ]

References

Dictionary of National Biography [ODNB]: ed. two ‘violent newspapers’, The Union Star and The Irish Magazine; forfeited pension. Note: There is no biog. article on Walter/Watty Cox in the Dictionary of Natioinal Biography 1885-1900 [online] - but there are several others in which he is cited, particularly as regards publications in his Irish Magazine - viz.:

Loius Perrin (1782-1864): [...] educated at the diocesan school at Armagh. Removing to Trinity College, Dublin, he gained a scholarship there in 1799, and graduated B.A. in 1801. At the trial of his fellow-student, Robert Emmet, in 1803, when sentence of death was pronounced, Perrin rushed forward in the court and warmly embraced the prisoner. He devoted himself with great energy to the study of mercantile law; in Hilary term 1806 was called to the bar, and was soon much employed in cases where penalties for breaches of the revenue laws were sought to be enforced. When Watty Cox, the proprietor and publisher of Cox’s Magazine, [sic], was prosecuted by the government for a libel in 1811, O’Connell, Burke, Bethel, and Perrin were employed for the defence; but the case was practically conducted by the junior, who showed marked ability in the matter. He was also junior counsel, in 1811, in the prosecution of Sheridan, Kirwan, and the catholic delegates for violating the Convention Act. In 1832 he became a bencher of King’s Inns, Dublin. [... &c] (Entry b George Clement Boase - online.]

Dennis Taaffe (?1743-1813): Watty Cox’s Irish Monthly is cited in the DNB article on Taaffe as reporting that he has reverted to his original Catholic faith after a period of apostasy and clerical employment in the Church of Ireland. As a member of the United Irish membership he suffered a wound at Ballyennis, from which he escaped in a hay-cart; fierce opponent of the Act of Union; Taaffe, who led a disreputable life and died in poverty while enjoying a £40 pa pension from Catholic bishop Dr. Carthy, wrote virulent pamphlets incl.

- The Probability, Causes, and Consequences of an Union between Great Britain and Ireland discussed, (Dublin 1798), 8vo.

- Vindication of the Irish Nation, and particularly its Catholic Inhabitants, from the Calumnies of Libellers, 5 pts. (Dublin 1802), 8vo.

- A Defence of the Catholic Church against the Assaults of certain busy Sectaries (Dublin 1803), 8vo.

- Antidotes to cure the Catholicophobia and Ierneophobia, efficacious to eradicate the Horrors against Catholics and Irishmen,’ (Dublin 1804), 8vo.

- Sketch of the Geography and of the History of Spain, translated from the French, (Dublin 1808), 8vo.

- [attrib.,] Ireland’s Mirror, exhibiting a Picture of her Present State, with a Glimpse of her Future Prospects’ (by ‘D.T.’), Dublin 1795), 8vo..

According to Cox, Taaffe he was fluent in several languages incl. Greek, Latin, Hebrew and oriental tongues. Though a nationalist, he opposed the French invasion of Ireland believing that France would promptly exchange Ireland for one of the sugar islands (Edward O’Reilly, Reminiscences of an Eminent Milesian). The article is by David J. O’Donoghue. [See DNB - online; accessed 04.07.2024.]

William Sampson: [...] Some verses by Sampson are in Madden’s Literary Remains of the United Irishmen, pp.122, 177, 179, and in Watty Cox’s Irish Magazine for 1811. (Entry by Gerald de Grus Norgate - DNB online.]

James Napper Tandy: bibl. cites Watty Cox, Irish Magazine, 1809, 52 [no ref given].

George Nugent Reynolds, - in Watty Cox’s ‘Irish Magazine,’ generally signed with his initials or ‘G—e R—s’ and ...

Patrick O’Kelly, - [Bibl.] Brit. Mus. Cat.; O’Donoghue’s Poets of Ireland; Croker’s Popular Songs of Ireland; Watty Cox’s Irish Magazine, September 1810. [Article by D. J. O’D ....]

Tandy, James Napper - the Public … in which several characters are involved, Dublin, 1807; Watty Cox’s Irish Magazine, 1809, p. 52; Abbot’s Diary, i. 445; Froude’s English ...

[ top ]

D. J. O’Donoghue, The Poets of Ireland: A Biographical Dictionary (Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co 1912); After his understanding to close the Irish Magazine with the British government [recte The Irish Magazine or Monthly Asylum for Neglected Biography, pub. 1807-1815], he travelled to American where he founded an unsuccessful newpaper and returned bankrupt, writing a bitter invective against that country in The Snuff-Box (1820). His strange career is traced and documented by Dr. Madden, Fitzpatrick and others, many thinking him a govt. spy. There are doubts as to his date of death, Glasnevin cemetery list giving his age as 84-20 yrs older than Madden and Webb, who agree in putting him at 66-67. See also Irish Book Lover, 5, 32.

Longer extract: (O’Donoghue, op. cit., p.84.)

Dictionary of Irish History, ed., Hickey & Doherty) relates that he ‘made a deal with Under-Sec. Edward Cooke to provide information on United Irishmen’; in other respects varies from OCIL, setting the date of his American journey before the founding of the Irish Magazine, but setting the date of his treaty and pension at 1816.

Brian McKenna, Irish Literature (Gale Research 1978), notes that Cox’s journalism appeared in the Union Star (Dublin 1797), Irish Magazine and Monthly Asylum &c (Nov 1807-Dec 1815), the New-Gate Register (Dublin ca.1815), the Exile (NY 1817-18), and the Mail Reviewed (Dublin 1823). Bibl., ‘Sketch of the Life of Mr. Walter Cox,’ in New Irish Magazine, and Monthly National Advocate, 1 (1822), p.38 [vicious criticism]; R. R. Madden, The United Irishmen, their Lives and Times (1842), II, pp.55-81; Seámus Ó Casaidhe, ‘Watty Cox and His Publications’ [Bibl. Soc. Ireland, 5] (1935), pp.17-38.

Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850 (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980), Vol. I; [A] character in Walter Cox’s The Widow Dempsey’s Funeral, is led out of sociability to wish his friends’ deaths the more frequently to enjoy the pleasures of the wake. [31; no bibl. note.] Bibl.: His works incl. Advice to Emigrants (1802); Remarks by One of the People (1804); A Short Sketch of the Present State of the Catholic Church in ... New York (1819); Bella, Horrida Bella (?1823); The Cuckoo Calendar, anecdotes of the Liberator ... the Great Mendicant (1833); also two plays, The Widow Dempsey’s Funeral (1822); The Coming of Aideen [also cited by Peter Kavanagh]. Some poems in Irish Magazine; he may have been the ‘Publicola’ who issued The Tears of Erin (1810). D. 7 [?] Jan., 1837.

Further: The Irish Magazine and Monthly Asylum reports unequal law, ‘On Thursday the 28th of May, two young and fashionable ladies of the name of Carroll, were tried before the Recorder and convicted of robbing several shops ... as was [sic] sentenced to one year’s imprisonment; at the same time a wretched, ragged female was convicted of stealing a shawl, value two shillings, and received sentence to be transported for seven years. We hope, with Lord Melville, that such salutary example will hereafter deter the poor from acts of dishonesty.’ (Vol II, p.272, Mar 1812).

British Library, Add. MS 35740 is an anonymous letter accusing Cox of revolutionary treason as body-guard to Lord Edward Fitzgerald.

Ulster Univ. Library holds Brendan Clifford, intro. and ed., The origin of Irish Catholic-Nationalism: selections from Walter Cox’s ‘Irish Magazine’, 1807-1 (Belfast: Athol Books 1992).

[Note: In catalogue searches - e.g., COPAC and NLI - <Walter Cox> or <Watty Cox> frequently throw up items written by Sir Richard Cox, the chief loyalist historian of the 1641 Rebellion in Hibernia Anglicana, or, The History of Ireland [2 pts.] (1689-90)- an ironic conflation of authors which only digital technology could supply. BS]

Notes

Fearflatha O’Gnimh’s famous poem ‘Mo Thruaigh Mar Táid Gaoidhil’ was first printed in The Irish Magazine & Monthly Asylum for Neglected Biography, III (Dublin 1810) [DIW].

Henry B Code , Burning of Moscow (Mar 1813), was noticed by Watty Cox in The Irish Magazine as a ‘heap of nausea, dullness, and plagiarism’ [PI].

Travelling Gallows: The BBC Educational folder on Ireland (1972) incl. illustrations from Cox’s Irish Monthly for 1801 [err. for 1807?] showing brutal British behaviour in 1798 including ‘Captain Swayne pitchcapping people in Prosperous [Co. Kildare],’ and ‘The Plan of a Travelling Gallows used in 1798’, details of Capt. Hempenstall and others [UUC LIB]. The engraving of the Travelling Gallows, by Henry Brocas,Snr. - who did several illustrations in the same vein for Cox - is available at the National Library of Ireland Cat. [onine]. Brocas was best-known for landscape watercolours of Dublin. His son and namesake perpetuated his topographical craft but failed as a teacher at the RDS.

| "Humbly dedicated to the Ancient and Modern Britons by the dutiful Serv" W. Cox. Actually by Henry Brochus (?1762-1837) who illstrated num. issues of Cox’s Irish Magazine and Asylum for National Biography (1807-1815). |

[ top ]