|

Aubrey [Thomas] de Vere (1814-1902)

Life

| b. Curragh Chase, Co. Limerick, 3rd son of his namesake [q.v.] and his wife Mary [née Rice]; ed. privately and TCD, BA 1837; contrib. to National Magazine and Dublin Literary Gazette as ‘A. T. de V’; worked in Famine relief, his English Misrule and Irish Misdeeds (1848) partly dealing with that event; dedicated his first book to John Henry Newman with whom he was closely associated; converted to Catholicism at Avignon en route for Rome, 1851 and wrote chiefly devotional literature thereafter; |

| |

| published The Waldenses (1842) [aet. 28], a ‘lyrical sketch’ [i.e., play] on the persecution of 1655 in Rora memorialised by Milton; also The Search after Proserpine (1843); verse collections incl. The Sisters (1861); The Infant Bridal (1864); Irish Odes (1869); Legends of St Patrick (1872), and Legends of the Saxon Saints (1879); Innisfail (1861) is a history of Ireland in a series of poems; prose works incl. Essays Chiefly on Poetry (1887); and Essays Chiefly Literary and Ethical (1889); dramas in verse, Alexander the Great (1874); and St Thomas of Canterbury (1876) and a volume of also travel-sketches; |

|

| |

| the friend of Wordsworth, Landor, Tennyson (whom he coached in Hiberno-English for a poem - as infra), and Browning; poems by him appeared regularily in the Irish Monthly; he was an original donor to the Irish Literary Theatre, 1898; notable poems incl. “The Little Black Rose”, and “The Year of Sorrow - Ireland 1849”; he remained unmarried; he edited his father’s sonnets and verse dramas in 1847 and 1884; d. 21 Jan. 1902. PI CAB JMC TAY MKA RAF DIW DIH FDA OCIL |

| See notice on the Vere family lineage - as attached. |

|

|

|

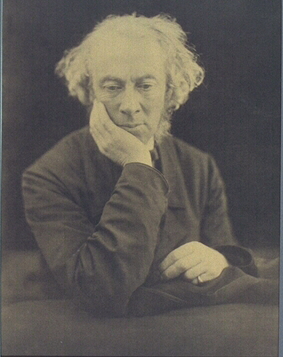

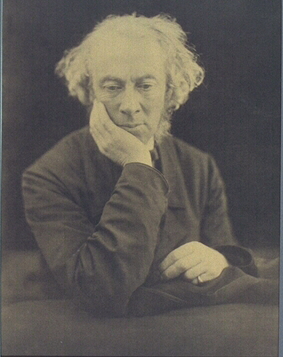

| Photo by Julia Margaret Cameron |

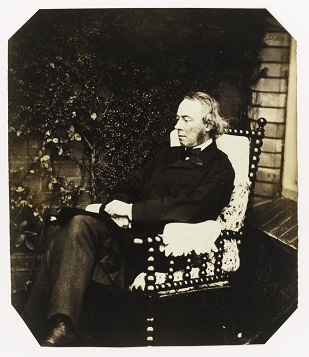

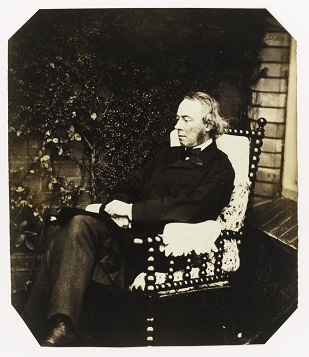

Photo by Lewis Carroll |

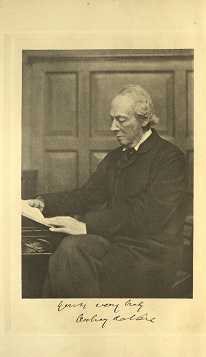

Recollections (1897) |

|

|

| Note: The central photo here was taken by Lewis Carroll on 5 September 1862 when visiting Sir Henry Taylor, who was married to de Vere’s first cousin Theodosia Spring-Rice, at his home in East Sheen, London. The resulting set of photos are held at Princeton but an albumen print (176 x 150mm) with slightly different dimensions was offered for sale in London in 2015. (See Richard Fattorini - British Photographic History page - online (9 Dec. 2015; accessed 21.06.2019; notified by Anne van Weerden.) |

[ top ]

Works

|

Poetry collections |

- The Waldenses or the Fall of Rora: A Lyrical Sketch, with Other Poems (Oxford: J. H. Parker; London: Rivingtons MDCCCXLII [1842]), xxi [Intro. [v]-vii], 311pp. [ded. to ‘The Astrnonmer Royal for Ireland, Sir William Rowan Hamilton’] contains ‘The Waldenses’, 1-92pp.; ‘Miscellaneous Poems’, 95ff. incl. ‘Hymns for the Canonical Hours’, 148ff., ‘Hymns for the Feast of the Holy Innocents’, 159ff., and ‘Sonnets’, 235-311pp. [available at Internet Archive - online]; reissued as The Fall of Rora, The Search [with] The Search after Proserpine, and Other Poems (London: H. S. King & Co. 1877), xiv. 392pp.

- The Search After Proserpine: Recollections of Greece, and Other Poems (Oxford: J. H. Parker London 1843), xii, 308pp. [contains ‘Search’; ‘Recollections’; ‘Miscellaneous Poems’; ‘Songs’; ‘Sonnets’].

- Poems (London: Burns & Lambert 1855), xii, 319pp. [ded. John Henry Newman], and Do. [3rd edn.] (1881).

- May Carols or Ancilla Domini (London: Longman, Green, Brown, Longmans, and Roberts 1857), xii, 126pp.; Do. [as May Carols, or The Month of Mary; 2nd enl. edn.] (London: Thomas Richardson; NY: Henry Richardson 1870), xl, 183pp.; Do. [3rd edn.] (1881); and Do., [new edns.] (NY: 1897 [1907]).

- The Sisters, Inisfail, and Other Poems (Lo: Longman; Dublin: McGlashan & Gill 1861).

- Inisfail: A Lyrical Chronicle of Ireland (Dublin & London: James Duffy 1863) [in 3 pts.], and Do. [another edn.] (London: Macmillan & Co. 1897), 436pp.

- The Infant Bridal [ ...] and Other Poems (London: Macmillan 1864), iv, 356pp.; and Do. [new & enl. edn.] (London: H. S. King 1876), iv. 377pp.

- Hymns and Sacred Poems (London: Richardson & Son 1864), 49pp. [engrav. Waller].

- Irish Odes and Other Poems (London [1869]; NY: Catholic Publ. Soc. 1869), xxii, 13-309 [297pp.].

- The Legends of St. Patrick, with a foreword by Henry Morley (Dublin: McGlashan & Gill; London: Henry S. King 1872), xxx, 248pp.; Do. [another edn.] (London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co. 1887), xviii, 310pp., and Do. [another edn.] (London: Cassell 1889), 192pp.

- Alexander the Great: A Dramatic Poem (London: H. S. King; Dublin: McGlashan & Gill 1874), xxiv, 231pp. [attrib. ‘calling himself earl of Oxford’; see note].

- St Thomas of Canterbury: A Dramatic Poem (London: H. S. King 1876).

- The Fall of Rora, The Search [with] The Search after Proserpine, and Other Poems (London: H. S. King & Co. 1877) [as supra]

- Antar & Zara: An Eastern Romance [with] Inisfail, and Other Poems Meditative and Lyrical (London: H. S. King 1877), xxxvi, 404pp. [incls. sonnets by the late Stephen Spring Rice, pp.251-76].

- [ed.], Proteus and Amadeus: A Correspondence (1878).

- Legends of the Saxon Saints (London: C. Kegan Paul & Co. 1879), lii, 289pp., and Do. [another edn.] ([London:] Macmillan 1893).

- The Foray of Queen Maeve and Other Legends of Ireland’s Heroic Age (London: Kegan Paul 1882), xxiv, 233pp., and Do. [reiss.] (London: Macmillan 1893) [verse; a telling of the Táin Bó Cuailgne].

- Legends and Records of the Church and the Empire (London: Kegan Paul 1887, 1893), xxviii, 310pp.

- St Peter’s Chains; or, Rome and the Italian Revolution (London: Burns & Oates; NY: Catholic Pub. Soc. [1888]), xii. 55pp. [sonnet series; date from pref.].

- Medieval Records and Sonnets (London: Macmillan 1893), xx, 270pp.

|

| [ top ] |

| Collected Editions |

- The Poetical Works of Aubrey de Vere, 8 vols. [Vols. 1-3, Kegan Paul; Vols 4-6 Macmillan] (London 1884-89) - of which Vol. 3 is entitled Alexander the Great, Saint Thomas of Canterbury and Other Poems (London: Macmillan, 1892); also Vol. 5: Inisfail: A Lyrical Chronicle of Ireland [contains] The Irish sisters; early poems, meditative or devotional; poems for the most part connected with the Great Irish famine, 1846-1849; Urbs Roma; St. Peter’s chains], xxxiii, 436pp.; see also electronic edn., (ProQuest LLC: Literature online 1996-2008) [6 vols.; prelim. and intro. matter omitted].

- John Dennis, ed., A Selection of the Poems of Aubrey de Vere (London: Cassell 1890), vi, 283pp. [attrib. ‘calling himself earl of Oxford’; see note].

- G. E. Woodberry, ed., Selected Poems (NY 1894).

- Lady Margaret Domvile, ed., Poems from the Works of Aubrey De Vere (London: Catholic Truth Soc. 1904), xx, 183pp.

|

| [ top ] |

| Prose |

- English Misrule and Irish Misdeeds: Four Letters from Ireland Addressed to an English Member of Parliament (London: J. Murray, 1848), iv, 265pp. [Printers: G. Woodfall & Son, Angel Court, Skinner Street, London; also 2nd edn. 1848], and Do. [facs. rep.] (NY: Kennikat rep. 1970), iv, 265pp; Do. [rep. edn.] (Cambridge: Chadwyck-Healey Ltd. 1997), 3 microfiches.

- Picturesque Sketches of Greece and Turkey, 2 vols. (London: Richard Bentley 1850, 1854).

- Essays Chiefly on Poetry [2 vols.] (London: Macmillan 1887), [of which Vol. 1: ‘Criticisms on Certain Poets’, 314pp., & Vol. 2: Esssays Literary and Ethical. pp.295.

- Essays Literary and Ethical (London: Macmillan 1889), viii, 329pp. [being Vol. 2 of Essays Chiefly on Poetry; see details]

- Religious Problems of the Nineteenth Century: essays by Aubrey de Vere, LLD, ed. J. G. Wenham (London: St. Anselm’s Society, 1893), 232pp.; another ed. (London: Mount Trenchard, Foynes, 28. xi 1893).

- Recollections (London & NY: E. Arnold 1897), vi, 374pp., front. [port.; available on Internet Archive - online.]

|

| [ top ] |

| Miscellaneous |

- Intro. to The Lawyer, his character and rule of Holy Life, after the manner of George Herbert’s Country Parson, by Edward O’Brien [Barrister-at-Law] (Philadelphia 1843) [introduction signed A. de V.; i.e. Aubrey Thomas de Vere.]

ed., Sonnets (1847).

- Preface to Heroines of Charity: containing the Sisters of Vincennes, Jeanne Biscot, Mlle le Gras, Madame de Miramion, Mrs Seton, The Little Sisters of the Poor, et al. (London: Burns & Lambert 1854).

- ed. Dramatic Works of Aubrey de Vere (1858) [his father].

- preface to The Church Establishment in Ireland: Illustrated Exclusively by Protestant Authorities (London: Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer; Dublin: Duffy 1867), xxx, 18-76pp.

- The Church Settlement of Ireland; or, Hibernia Pacanda (London: Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer; Dublin: Duffy 1866), xxxi, 66pp. [2 edns. in 1866].

- Ireland’s Church Property and the Right Use of It (London: Longmans, Green, Reader& Dyer; Dublin: Duffy 1867), 60pp.

- Pleas for Secularization (London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer 1867), xii, 46pp.

- Reply to Certain Strictures by Myles O&’Reilly, Esq., being a postscript to Pleas for Secularization (Dublin: Duffy 1868; London: Longmans, Green, Reader, & Dyer 1868), 26pp.

- with others, contrib. commemorative verses to David Moriarty [1814-1877; RC bishop of Kerry], The Laying of the Stone: A Sermon [on the occasion of the laying the first stone of [...] St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth, Sunday, 10 Oct. 1875; feast of the Dedication of all the Churches of Ireland] (Dublin: McGlashan & Gill 1875) [others being Robert French Whitehead, and Joseph Farrell].

- ed. Proteus and Amadeus: A Correspondence (London: Kegan Paul & Co. 1878), xxi, 184pp. [Wilfred Scawan Blunt and Charles Meynell on existence of God].

- Proportionate Representation: The Idea Involved in It (1886) [orig. in Dublin Review, Jan. 1886]

- Introductory letter to The Apostle of Ireland and His Modern Critics by W. B. Morris (London: Burns & Oates 1881) p.3 [orig. as essay in the Dublin Review, July 1880].

- Constitutional and Unconstitutional Political Action: letters by A. de Vere (Limerick: G. M’Kern & Sons 1881) [q.pp.]

- ‘Characteristics of Spenser’s Poetry’, in The Complete Works in Verse and Prose of Edmund Spenser [... &c.]. ed. Alexander B. Grosart (1882-84), Vol. I, pp. 257-303 [4o.].

- Ireland’s Proportional Representation ( Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co.; London: W. Ridgway 1885), 44pp. [1 microfiche edn. Chadwyck-Healey 1987].

- ed., The Household Poetry Book : An Anthology of English-speaking Poets from Chaucer to Faber, with biographical and critical notes (London: Burns & Oates Ltd. 1893), xii, 308pp.

- The Genius and Passion of Wordsworth ([s.n.; s.l.] ?1902), rep. from Reprinted from The Month and Catholic Review.

|

| |

See also Inaugural Address delivered ... at the house of the Limerick Philosophical and Literary Society (Dublin: Grant & Bolton; London: William Pickering 1842), 45pp. [note British Library author listing as Hunt, afterwards Aubrey de Vere, Bart.]

|

| |

| |

| [See also listing of holdings at the National Library of Ireland - infra.] |

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Essays Literary and Ethical (London: Macmillan 1889), viii, 329pp. [being Vol. 2 of Essays Chiefly on Poetry]. CONTENTS: Some remarks on literature in its social aspects; Archbishop Trench’s poems; Poems by Sir Samuel Ferguson; Coventry Patmore’s poetry; A policy for Ireland, January 1887; Proportionate representation considered with reference to the idea involved in it; Church property and secularisation, 1867; A few notes on modern unbelief; Some remarks on the philosophy of the rule of faith; The personal character of Wordsworth’s poetry.]

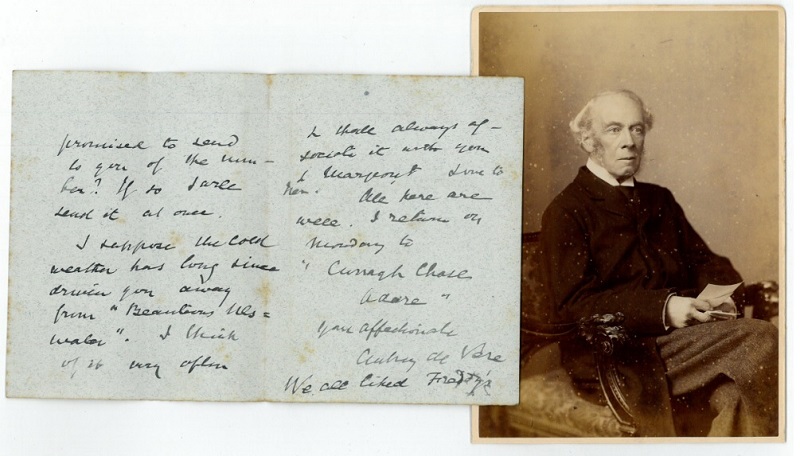

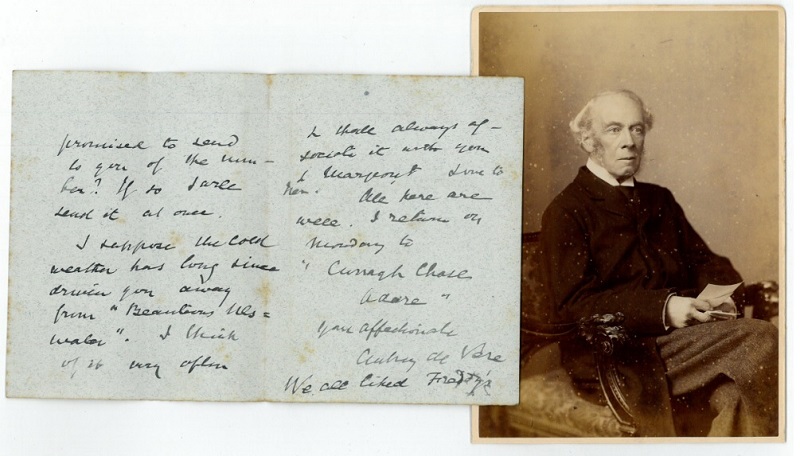

| An Autograph Letter by Aubrey Thomas De Vere |

|

Offered for sale by Antiquariat INLIBRIS Gilhofer Nfg. GmbH (Vienna) 22 Nov. 2000; posted on Abebooks UK - online;

copied in Web Archive - online; accessed 03.01.2023 on information supplied by Anne van Weerden. |

|

Bookseller’s notice: ‘mall 8vo. 3 pp. on bifolium. Together with a cabinet photograph. To his ‘dear Agnes’: ‘I have only just learned that several copies of my Vol. of Essays ('Religious Problems' etc.) which I directed my publishers to forward to various friends were never sent. Was the one I promised to send to you of the number? If so, I will send it at once[...]’ De Vere refers to his just-published ‘Religious Problems of the Nineteenth Century" (1893). - Slightly spotty, small traces of mounting along the edge of the final page.’ (INLIBRIS &c. - as supra.)

|

See also a letter listed by Richard Ford, Ltd., London, addressed to Samuel Waddington permitting to publish a sonnet by De Vere in an anthology, with further remarks on Hartley Coleridge, William Wordsworth, and Sir Aubrey de Vere. (Available at Abebooks - servlet [Nov. 1997; no ill.]; accessed 03.01.2023.

|

|

[ top ]

Criticism

- [q. auth.,] ‘The Poems of the de Veres’, in Dublin University Magazine (Feb. 1843).

- Sir Henry Taylor, Notes from Books: In Four Essays [2nd edn.] (London: John Murray 1849), [vii]-xviii, 295p. incls. [The poetical works of Mr. Wordsworth; Mr. Wordsworth’s sonnets; Mr. De Vere’s poems; The wave of the rich and great].

- Review of The Sisters of Innisfail and Other Poems, by Aubrey de Vere and Shakespere’s Curse and Other Poems [by A.N.Other], in The Dublin University Magazine: a Literary and Political Journal, Vol. LVIII (Sept. 1861), pp.345-50 [available online].

- J. P. Gunning, Aubrey de Vere: A Memoir (Limerick & London, 1902).

- Wilfrid Ward, Aubrey de Vere: A Memoir (London 1904), x, 428pp., ports [incls. Appendix: ‘Aubrey de Vere’s Philosophy of Faith’, pp.[411]-16].

- Theodorus Adrianus Pijpers, Aubrey de Vere as a Man of Letters [Academisch proefschrift, &c.] (Nijmegen, Utrecht: Dekker & Van de Vegt [1941]), viii, 224pp.

- Sr. M. P[araclita] Reilly, Aubrey de Vere: Victorian Observer (Univ. of Nebraska, 1953; Dublin: Clonmore & Reynolds; London: Burnes, Oates & Washbourne 1956), 180pp. [Bibl., pp. 167-74].

- P. A. Winckler & W. V. Stone, ‘Aubrey de Vere 1814-1902: A Bibliography’, in Victorian Newsletter, 10 [Supplement] (1956) pp.1-4.

- Herbert V. Fackler, ‘Aubrey de Vere’s The Sons of Usnach (1884): A Heroic Narrative Poem in Six Cantos’, in éire-Ireland 9, 1 (1974), pp.80-89.

- Robert Welch, ‘An Attempt at a Catholic Humanity’ [Chap.], in Irish Poetry from Moore to Yeats [Chap. 5] (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980), pp.156-77 [see extract].

- Chris Morash, ‘The Little Black Rose Revisited: Church, Empire and National Destiny in the Writings of Aubrey de Vere’, in Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, 20, 2 (Dec. 1994), pp.45-52 [extract].

- Chris Morash, ‘The Little Black Rose Revisited: Church, Empire and National Destiny in the Writings of Aubrey de Vere’, in Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Dec. 1994), pp.45-52 [see infra]

- Patrick J. Cronin, Aubrey de Vere: The Bard of Curragh Chase: A Portrait of His Life and Writings (Askeaton Civic Trust 1997), viii, 232pp., ill. [ports.], with sel. poems and sonnets; Bibl. pp.228-29].

|

| See further under Commentary, infra. |

[ top ]

Commentary

S. T. Coleridge - See implied reference to his English Misrule and Irish Misdeeds ( 1848) in S. T. Coleridge, Essay on His Own Times, ed. by his Daughter (Pickering 1850) - Introduction [by his dg.]: Irish chapters - as given under James Joyce, infra.

W. P. Ryan, The Irish Literary Revival (London: 1894), remarks, ‘Mr Aubrey de Vere has justly said that poetry refused to take up more philosophy than it can hold in solution’ (p.148)

W. B. Yeats remarked that, in spite of Inisfail and The Foray, de Vere is better known as a poet of the English Catholics than as an Irish writer: ‘Something may be due to a defect of genius, for he seems to me, despite his noble placidity, his manifold and moving exposition of Catholic doctrine and emotion, but seldom master of the inevitable words in the inevitable order, and I find myself constantly distinguishing, when I read him, between that calculable, considered, intelligible and pleasant thing we call the poetical, and that incalculable, instinctive, mysterious, and startling thing we call poetry.’ (Uncollected Prose, ed. J. P. Frayne, Macmillan 1970, p.381; quoted in Robert Welch, Irish Poetry from Moore to Yeats (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980; as infra.)]

A. P. Graves, Irish Literature and Drama (London: Nelson 1936): ‘Aubrey de Vere, who so often in his poetry chose Ireland for his subject and whose deeply religious mind was possessed by the same faith as his Gaelic fellow-countrymen.’ (p.110); Tennyson went to Clare on Aubrey de Vere’s instructions looking for ‘the most magnificent waves’. See especially “Tennyson in Ireland;” 1842; [first of two visits]; persuaded by Aubrey de Vere to visit Ireland to see the largest waves in the British Isles, 1842; toured West with de Vere, of Curragh Chase: ‘lawn tennis’. [Encountered by Graves in 1878 when he and his son were guests of Lord and Lady Monteagle; ‘there was a rich burr in his accent, Lincolnshire, I suppose, and a pungent directness of utterance which were as refreshing as they were unlooked for’; in 1848, Tennyson in Kerry, looking for big seas, followed by conspirator: ‘Be ye from France?’ Further: Tennyson told Graves ‘that he much desire to write an Irish poem, and was on the look-out for a suitable subject. Could I make a suggestions? [A. P. Graves] sent Joyce’s Old Celtic Romances [cited by Hallam as Celtic Legends] Hallam continues: ‘By this story he intended to represent in his own original way the Celtic genius, and he wrote the poem with a genuine love of the peculiar exhuberance of the Irish imagination.’ [9; cont.]

A. P. Graves (Irish Literature and Drama, 1936) - cont.: Graves regrets that Tennyson had not read O’Grady’s Silva Gadelica: ‘I make no doubt he would have given us a saga immeasurably more true to the Celtic spirit than his ‘Voyage of Maeldune’ … deeply interesting though it is as a great English poet’s attempt to express the Celtic genius.’ [10] Tennyson’s other Irish poem, ‘To-morrow,’ is founded on the story told him by Aubrey de Vere. Hallam T. notes, he corrected his Irish from Carleton’s Traits &c., a proof of the poet’s extraordinary laboriousness, and a crying comment on the want of an Anglo-Irish or Hiberno-English dialect dictionary. … deeply sensible to the tragic side of Irish peasant life … an interesting assertion of his belief in the artistic value of Irish dialect in verse: Irish Doric, as he once wrote of it to me.’ Tennyson attests to ‘what is peculiar to the Irish imagination’; ‘“Fr O’Flynn” was not wanted by Stanford and Boosey for collection, but the singer Sankey liked it; Stanford and Boosey got thousands for it, but Graves got £1.12.0; ‘I still have hopes from the talkies’; joined pan-Celtic Conference in Dublin (Lord Castletown and M. Fournier d’Albe; called his Harlech house ‘Erinfa’, Welsh, towards Ireland. Irish Doric; Tennyson had referred to Songs of Killarney as ‘your Irish Doric; Graves had 50 year connection with Stanford; “Fr O’Flynn” published in Spectator, and found favour as a song 10 years after (Sankey); ‘many years of happy acquaintance with the Kerry peasantry’ and ‘that beautiful county ... their home and mine’; Songs of the Gael, pref. Douglas Hyde; also Hyde, pref., Irish Songs, ‘I never used to open Lover that I was not reminded more or less of Graves, nor opened Graves that I was not reminded of Lover’ 0p. vi); ‘neither Callanan nor Mangan could have caught the Irish tone and conception more truly’. Graves, ‘lovable traits of Kerry peasants which so endeared them to my f. and m. and all of us a children at Parknasilla years ago’ on behalf of Kerry, he hopes for ‘an abiding rest ... after the reckless internecine war in which it had been so long and so cruelly plunged’ (1926; Selected Poems, i.e., Irish Doric).

| Poem Finder |

[...] The characteristics of Aubrey de Vere’s poetry are high seriousness and a fine religious enthusiasm. His research in questions of faith led him to the Roman Catholic Church; and in many of his poems, notably in the volume of sonnets called St Peter’s Chains (1888), he made rich additions to devotional verse. He was a disciple of Wordsworth, whose calm meditative serenity he often echoed with great felicity; and his affection for Greek poetry, truly felt and understood, gave dignity and weight to his own versions of mythological idylls. But perhaps he will be chiefly remembered for the impulse which he gave to the study of Celtic legend and Celtic literature. In this direction he has had many followers, who have sometimes assumed the appearance of pioneers; but after Matthew Arnold’s fine lecture on Celtic Literature, nothing perhaps did more to help the Celtic revival than Aubrey de Vere’s tender insight into the Irish character, and his stirring reproductions of the early Irish epic poetry. A volume of Selections from his poems was edited in 1894 (New York and London) by G. E. Woodberry.

|

| Available online; accessed 20.06.2019. |

| Poems listed |

|

|

|

Robert Farren, The Course of Irish Verse (Dublin 1948), remarks: ‘The Catholic poet - even the gentleman convert - was still unhelped by the cultural milieu [to Irishize his work]. There were still two atmospheres, and the older resisted the new. ... Sir William Wilde introduced him as ‘my Papist friend’ ... his watery gentility thinned most of what he made [...]’(p.44ff.)

Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, Vol 1 (1980), remarks that Aubrey de Vere railed against ‘colonisation’ (Dublin University Magazine XXXIV, 199, July 1849, p.110. [138]

W. B. Stanford, Ireland and the Classical Tradition (IAP 1976; 1984) calls Aubrey de Vere’s Alexander the Great (1874) ‘little more than academic exercise’ (p.92); Further, Aubrey de Vere’s classical poems praised extravagantly by W. S. Landor, ‘nothing in our days will bear a moment’s comparison with them, nor do I find anything more classical among the best of the ancients’; on Search for [sic] Proseperine [recte Proserpine] (1843), ‘it is the first time I have felt hellenised by a modern hand’. Search &c., contains choruses of fauns, naiads, and nerieds; also, his Greek Idyls, his sonnets on Greek themes, his verses on Sophocles and Delphi, show a well-digested knowledge of classical and modern Greece, as do his Picturesque Studies of Greece and Turkey, 2 vols. (1850), and a deep admiration for the higher Greek ideals. The essay on Landor’s poetry in the first volume of his Essays Chiefly on Poetry (1887) presents a good critical survey of previous neo-classical poets [in English] and perceptive things about Greek landscape and religious feelings’ (ibid., p.93); further: ‘Aubrey de Vere, in his Essays (1887) he found reasons for praising some aspects of Greek religion; fundamentally, however, he found it deficient in ‘spirituality’ and unsympathetic to ‘religious zeal’ and ‘obedience as a law of life.’ Stanford comments, In general de Vere gives the impression of a writer in whom temperament and artistry were never fully integrated. As an artist he was drawn to Greece and disliked the Latin tradition, but temperamentally he was drawn to the more realistic Roman tradition. He was received into the Roman Catholic Church in 1851 (ibid., 242).

[ top ]

Robert Welch, ‘An Attempt at a Catholic Humanity’, in Irish Poetry from Moore to Yeats [Chap. 5] (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980), pp.156-77: calls de Vere deeply conservative [...]; Curragh Chase, Co. Limerick, near Adare Manor, of the Dunraven family ... a tutor, Edward Johnstone, drew [his] attention to Wordsworth ... his f. Sir Aubrey, a “Canningite”; at Catholic Emancipation, young Aubrey climed to the top of a pillar opposite the house and waved a torch in the gathering darkness; his brother Stephen accompanied peasants on emigrant ship in the late 1840s (see Aubrey De Vere, Recollections [1897]); Aubrey approved Gladstone’s Land Act of 1881; like Ferguson believed in the importance of an elite ... and despised the ‘Jacobinal’ tendency. [...] Attracted by Tractarian Movement at Oxford, which argued that the church should take it upon itself to interpret faith and belief; De Vere met Newman in Oxford in 1838 and was impressed by his air of sanctity and otherworldliness, comparing him to some ‘youthful ascetic of the middle ages’ [Recollections]. [...] Went to Cambridge; his cousin, Stephen Spring-Rice, author of bleakly introverted sonnets and member of Apostles Club at Cambridge; Tennyson and F. D. Maurice, the theologian, also members; both had profound influence on him; de Vere writes a mock-heroic denunciation of the Apostles in a letter to his cousin, Stephen Spring-Rice, printed in Ward’s Memoir, ‘Are you not ironical persons? Is it not your creed that everything is everything else?’ [...] De Vere impressed by Coleridge’s distinction between higher Reason and mere Understanding - the intuitive and the mechanical. On the Church, ‘Of all the thoughts at the moment going on, in the brains of men, not one in a thousand has anything that answeres to either in pures reason or the truth of things. What, then, if Religion, instead of holding forth a substance of Reality in the midst of this phantom dance, forgets her peculiar and positive function - watches the maniacs till she goes mad, catches the impulse and joins the rout?’ [Ward’s Memoir, p.52]. (Cont.)

Robert Welch (‘An Attempt at a Catholic Humanity’, in Irish Poetry from Moore to Yeats, 1980): Welch argues that religio means to bind. [...] Received into the Roman Catholic Church in 1851, at Avignon, on his way to Rome. Welch comments that, in comparison to the Irish Protestant Anglicanism of Ferguson, de Vere ‘saw beyond the Irish context, was aware of the great theological issues of the mid-century, and this gives his Catholicism an obviously English flavour.’ [Irish Poetry, 159-60] [...] Holding that the Irish as a race had not yet reached true adulthood ... he was, as a Wordworthian, imaginatively attracted to their history. ... a prolonged meditation on Ireland’s history would clarify the lineaments of her true identity [as] that of child, pure, innocent, spontaneous. Ireland’s vocation in the world was, like that of Israel, a spiritual one. (Recollections, 354). It was his purpose to trace the divine pattern in her historical subjection. [...] Her Fatalism meant simply a profound sense of Religion. The intense Theism which has ever belonged to the East survived in Ireland as an instinct no less than as a Faith. The Irish have commonly found it more easy to recognise the Divine hand than secondary causes. They have regarded Religion as the chief possession of man. Such nations are ever attached to the Past. [Aubrey de Vere, Introd., Inisfail, 1861] [...] Audience with Pius IX, whom he found strong, fat, and genial. Wrote May Carols or Ancilla Domini in response to the Pope’s request that he write a poems in honour of the BVM and the saints. Legends of St. Patrick and Legends of the Saxon Saints answers to the second injunction. [...] Tennyson had read In Memoriam to him with tears running down his cheeks; May Carols in written in the same quatrains. [...] May Carols, an attempt at a poetry of spiritualised humanity. March was ‘religion itself in its essence’; through her, ‘Holy Church keeps a perpetual Christmas’ (May Carols, preface). The sequence is not particularily successful ... pleasant if uninspired description leading to the conclusion that earthly beauty is evidence of God’s design for us and analagous to the beauty and purity of Mary. Qelch quotes: ‘The Irish, as a race, are the more impulsive, more sanguine, more imaginative, tenderer in love, and fiercer in hate. The english are stronger, more reliable, and juster. The Irish are more sympathetic, the English more benevolent.’ (Recollections, 356). [...; cont.].

Robert Welch (‘An Attempt at a Catholic Humanity’, in Irish Poetry from Moore to Yeats, 1980) - cont.: Hon. Professor of English Lit. at Newman’s College for a time. Wrote a vast amount of verse at Curragh Chase. Further, remarks on individual works: Inisfail was conceived as a spiritual biography of the Irish people; quotes, ‘the main scope of the poem which illustrates the interior life of a nation - the biography of a People - must be spiritual’; missionary calling, to instruct more advanced nations; de Vere ‘uses rhythms which have the aim of representing Irish rhythms, as Larminie, Sigerson, Hyde and Todhunter were later to do.’ On English Misrule and Irish Misdeeds (1848) accuses England of lack of sympathy and advocating a systematic emigration as a policy for alleviating Ireland’s difficulties. Ran relief committees with his brother during the famine, and visited badly-hit Kilkee. His traumatic exposure to famine-suffering recalled in Recollections. Ten years later we find the imagery of famine haunting the recall of 16th c. Irish wars in Inisfail. Poems in Inisfail incl. ‘The Bard Ethell’, an extended monlogue; ‘The Wedding of the Clans, or A Girl’s Babble’, spoken by a girl distressed to be made marry a Norman lord; ‘The War-Song of Tirconnell’s bard at the battle of Blackwater’ (1598); ‘Sibylla Iernensis’, a dream-poem arising from irish sufferings, and occasioned by the reading of O’Donovan’s Annals of the Four Masters (‘The Sibyl and that volume’s spells / Pursued me with those funeral bells!’); ‘The Wheel of Affliction’, telling in imitation Gothic of the saints, queens, kings and priests of vanquished Ireland; ‘Unrevealed’, dealing with his bafflement at the absurdity of Irish history (‘Thy song’s sweet rage but indicates / That mystery it can ne’er reveal’). On The Foray of Queen Maeve (1882) is based on Brian O’Looney’s MS translation of the Tain in the RIA, and attempts to translate the strength of heroic virtue into late Victorian Miltonic blank verse; ... showing the native nobility of Irish humanity, how ready it was for the leaven of Christianity. (Robert Welch, op cit., 1980, pp176, 177.)

[ top ]

P. J. Kavanagh, Voices in Ireland (Murray 1994): There are two literary Aubrey de Veres. The first, poet and friend of Wordsworth, b. at Curragh Chase in 1788, died 1846; and his son, poet and friend of Tennyson, b. at Curagh Chase in 1814, died 1902 ... At his first invitation to Curragh Chase, in 1842, Tennyson somehow missed de Vere in London and set off for Ireland by himself, to spend a lonely fortnight wandering from Limerick and Killarney down to Cork. Tennyson got to Curragh Chase six years later, in c1848, having previously stipulated that he would only come if he was not expected to come down to breakfast, could have half the day alone, could smoke in the house, and there should be no talk of Irish distress. (p.140). FURTHER ‘At the far end of the Iveragh Peninsula is Valentia Island, where Aubrey de Vere sent Tennyson to list ton the waves pounding in, promising him they would make the waves of Mablethorphe or Beachy Head sound puny. Had Tennyson heard about the magic Waves of Ireland. At Valentia he said that their sound made all the revolutions of Europe dwindle into insignficance. he had also sought waves on his previous Irish trip of 1842, when he visited the seacaves at Ballybunion in N. Kerry, and is said to have stored up an image from them: ‘So dark a forethought rolled about his brain, / As on a dull day in an Ocean cave / The blind wave feeling round his long sea-hall / In silence ... // Later in his life Tennyson tried his hand at a poem (”Tomorrow”) in Irish dialect, helped by William Allingham [‘the poem concerns a young man lost in the bog whose preserved body, found after, causes his former lover, now old, to drop dead’]: ‘Och, Molly, we thought, macree, ye would start back agin into life, / Whin we laid yez, aich by aich, at yet wake like husban’ and’ wife. / Sorra the dhry eye thin but was wet for the frinds that was gone! ... / An’ now that I tould yer Honour wativer I hard an’ seen, / Yer Honour ’ill give me a thrifle to dhrink yer health in poteen.’ (pp.193-94.)

Chris Morash, ‘Aubrey De Vere & the Religious Response’, in The Hungry Voice (Dublin IAP 1989), pp.82-92; selects “The Desolation of the West” (Irish Odes and Other Poems NY: The Catholic Publ. Soc., 1869, p.40); “Ireland, 1851”; “Irish Colonization, 1848” [‘England, thy sinful past has found thee out! […]’; printed in Dublin University Magazine, 34, 199 (1849); “Ode: After One of the Famine Years”; from “The Sisters, or, Weal in Woe”; “Widowhood, 1848”; “The Year of Sorrow, Ireland - 1849” [sects. “Spring”, “Summer”, “Autumn”, “Winter”] - all from Irish Odes and Other Poems (1869). In 1882 de Vere published a verse trans. of Táin Bó Cuailgne called The Foray of Queen Maeve; spent much of the Famine on his estate, and in 1848 wrote about the state of Ireland in English Misrule and Irish Misdeeds. Further: ‘There is a stately, almost languid elegance to the world of “moontide ghosts” of De Vere’s Famine poetry ... De Vere’s Famine poetry takes an essentially preterist [?preterite] stance; the apocalypse has taken place, and it is now time to look to the New Jerusalem ... he does not think of the golden age to be ushered in by the suffering of the Famine in political terms. For De Vere’s interpretation of the Famine was rather ‘conviction that for earthy scath / In worldwide victories of her Faith / Atonement should be made’ [and] ‘God’s concealed intent / Converts his worst to best / the first of altars was a tomb - / Ireland! thy gravestones shall become / God’s altar in the west!’ (“The Desolation of the West”). He poses the question, ‘why should a lute prolong a sigh, / Sophisticating sorrow?’ Further: ‘When De Vere equates the Famine dead with the “saints and seers of earlier times” he is creating a context in which the deaths of the anonymous thousands who died of starvation and disease have a meaning. His Christian stategy parallels that of the nationalist writers who attempted to include the Famine dead among the pantheon of martyrs who died for Irish freedom.’ (pp.31-34.)

Chris Morash, ‘The Little Black Rose Revisited: Church, Empire and National Destiny in the Writings of Aubrey de Vere’, in Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Dec. 1994), pp.45-52 - Bibl. cites works of Aubrey [Thomas] De Vere: Colonization (London: Spottiswoode & Shaw 1850); Ireland: Her Present and Her Future London: Spottiswoode 1880); Irish Odes and Other Poems (NY: The Catholic Publications Society 1869); The Poetical Works of Aubrey De Vere, 6 vols. (London: Macmillan 1897); Recollections. (London & NY: Edward Arnold 1897); Wilfred Ward, Aubrey De Vere: A Memoir Based On His Unpublished Diaries and Correspondence (London: Longmans, Green & Co. 1904).

[ top ]

|

[Frank McNally,] “Irishman’s Diary”, in The Irish Times (21 March 2002) |

| |

Do you recall these stirring lines from your childhood classroom?

“Does any man dream that a Gael can fear?

Of a thousand deeds let him learn but one!

The Shannon swept onward broad and clear,

Between the beleaguers and broad Athlone”.

The poem is A Ballad of Athlone and is based on an incident that took place during the second siege of the town in 1691. It celebrates the brave action of a dozen men who managed to destroy the bridge over the Shannon and thus slow the advance of the Williamite army under General Ginkel.

Aubrey de Vere wrote the poem, but who remembers him today? Although the centenary of his death (January 21st) passed without mention so far as I know, his centenary year should not be allowed to pass without calling some attention to his achievements. That one of his collections of poems had the title The Legends of St Patrick makes this an appropriate time for recollection.

Aubrey Thomas de Vere, the son of Sir Aubrey de Vere, himself a poet, was born at Adare, Co Limerick on January 10th, 1814. He was educated at Trinity College Dublin and afterwards moved to England where he spent much of the rest of his life. As a young man he got to know the foremost poets of the day. He befriended William Wordsworth, who greatly influenced him, and through Wordsworth he met Samuel Taylor Coleridge, another giant of the Romantic movement.

Later in life he was friendly with Alfred Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning, arguably the two greatest poets of the Victorian period. He also maintained a friendship with Walter Savage Landor - no small achievement, given that poet’s notoriously quarrelsome character.

De Vere was raised in the Anglican faith but in England he came under the influence of the Tractarian movement and especially of the two leading lights in that movement: John Henry Newman and Henry Edward Manning. He followed a similar path to both of them, and was received into the Roman Catholic Church in 1851. It is likely that his sympathies, which were strongly drawn to Ireland and her people, predisposed him to this move.

He was a prolific writer, producing literary criticism such as Essays Chiefly on Poetry (1887) and writings on political topics as well as verse. Among his volumes of poetry not specifically on Irish subjects were The Waldenses (1842), The Search after Prosperine (1843) and May Carols (1857). But he is mainly remembered - and would probably want to be remembered - for his writing on Irish themes.

He wrote in prose about the injustices visited on Ireland by English misgovernment, such as in his English Misrule and Irish Misdeeds (1848), but these works are little read nowadays. Irish history and legend inspired virtually all of the poetry he wrote in the second half of his life. His collection Innisfail (1861), for example, is a history of Ireland in a series of poems. The titles of the collections The Foray of Queen Maeve (1869) and The Legends of St Patrick (1872) are self-explanatory.

From his name one may presume he was of Norman descent. One of his more anthologised poems is In Ruin Reconciled. It considers how the vagaries of Irish history brought the Norman and Gaelic Irish traditions to fight side by side against a common foe which eventually destroyed them both. The poem has a number of memorable images: a woman’s voice wailing “between the sandhills and the sea”; a “famished sea-bird” sailing “into the dim infinity”; wide, rainy moors on which a great rock looms, which turns out to be a tomb. Before the tomb are two queenly shapes: “Two regal shades in ruined state / One Gael, one Norman, both discrowned”.

One of his most beautiful short poems is The Little Black Rose. It is similar to James Clarence Mangan’s Dark Rosaleen. The opening lines are: “The little black rose shall be red at last! / What made it black but the East wind dry?” The poem borrows some of its images from well-known poems in the Irish language such as An Droimeann Donn Dilís.

The poet looks forward to the day when Ireland would be free. “The Silk of the Kine shall rest at last! / What drove her forth but the dragon-fly? / In the golden vale she shall feed full fast / With her mild gold horn, and her sloe-dark eye.”

Aubrey de Vere belongs to an important and honourable tradition in our country’s poetry in both the Irish and English languages. He should not be forgotten.

|

| —Available at The Irish Times - online; accessed 20.06.2019. |

[ top ]

References

|

National Library of Ireland - Electronic Catalogue at 20.06.2019) |

| Short listing (main citation - Inisfail, &c.) |

- Literary notices: “The infant burial and other poems” by Aubrey de Vere reviewed (1876).

- Seven notebooks containing reflections and musings of Aubrey de Vere on religious and other matters, 1842-1849.

- Two new “May Carols”. “O cowslips sweetening lawn and vale”. “The golden day is dead at last” (1874)

- A few notes of letters and books sent and received by Aubrey De Vere, 1899.

- Four small note-books of personal memoranda, addresses, etc. by Aubrey De Vere, 19th c.

|

| |

| NLI - The complete listing |

- Sonnets on colonisation beginning “England, thy sinful past has found thee out”.by De Vere, Aubrey Published 1849.

- The Dublin University magazine: a literary and political journal, Vol. XXXIV, p. 110, p. 242, July, August 1849.

- Sonnets: on the consecration of Ireland to the Sacred Heart, Passion Sunday, 1873. Poem beginning “Lift up Thy gates, triumphant Heart Eterne”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. I, p. 10, July 1873.

- Lines, being a poem beginning “Since last with thee, my guide unseen”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. I, p. 129, September 1873.

- ”How came there sin to world so fair”: a poem beginning with same line, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. I, p. 361, December 1873.

- Pastor Aeternus: a poem beginning “I scaled the hills. No murky blot”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. II, p. 219, April 1874.

- Two new “May Carols”. “O cowslips sweetening lawn and vale”. “The golden day is dead at last”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. II, p. 300, May 1874.

- The Daughters of Mary. A May Carol beginning “From sin - but not alone from sin - ”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. III, p. 338, May 1875.

- Sonnet on a fresh outbreak of detraction against the Church: “Revolted province of the Church of God” in The Irish Monthly, Vol. III, p. 470, July 1875.

- Sonnet: on the laying of the Foundation Stone of the new Church of St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth beginning “Not vain the faith and patience of the sainte.” in The Irish Monthly, Vol. IV, pp. 14-15, December 1875.

- Literary notices: “The infant burial and other poems” by Aubrey de Vere reviewed, in The Dublin University Magazine: A Literary and Political Journal, Vol. LXXXVII, pp. 124-128, January 1876.

- Fountain’s Abbey: a poem beginning “The hand of Time is heavy: yet how soft”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. V, p. 17, December 1876.

- The dirge of Desmond: a poem beginning “Rush dark dirge, o’er hills of Erin”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. V, pp. 314-315, May 1877.

- Saint Joseph: a poem beginning “Ho ye that toil and ye that spin”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. VI, pp. 131-133, March 1878.

- Sonnets in memory of Sir William Hamilton Rowan beginning “Friend of past years, the holy and the blest”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. VIII, p. 674, December 1880.

- Filia Mariae: a poem beginning “One thought alone ’mid all this sea”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. IX, p. 278, May 1881.

- Genius and sanctity: a couplet beginning “How high he soars”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XI, p. 74, February 1883.

- Death: a poem beginning “Why shrink from Death? In ancient days we know”, The Irish Monthly, Vol. XI, p. 100, February 1883.

- Age: a poem beginning “Old age! The sound is harsh and grates”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XI, p. 162, March 1883.

- An autumn song: beginning “O fading flower, O faded leaf”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XI, p. 330, June 1883.

- Oisin the bard and St. Patrick: a poem beginning “Patrick, ‘tis right thy house should roof”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XII, pp. 10-12, January 1884.

- The dethronement of the Pope: a poem beginning “No, Italy, that deed was never thine”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVI, p. 409, July 1888.

- St. Peter’s chains: a review of his sonnets on the Italian Revolution, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVI, pp. 607-615, October 1888.

- Montalembert and De Merode: a sonnet beginning “Montalembert! De Merode! Linked were ye”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVI, p. 677, November 1888.

- St. Chrysostom’s return from Exile: a poem beginning “Sad is the music through the midnight seas”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVII, p. 200, April 1889.

- Sonnets: I. Mary, Queen of Scots: beginning “Strong land by Wallace trod and Bruce: brave land”. II. The Prince of Wales tribute to Fr. Damien: beginning “ ‘twas just! Fanatic’ [by Aubrey de Vere], in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVII, p. 640, December 1889.

- Unpublished letters of Aubrey de Vere, by Rev. Matthew Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXXIX, pp. 421-9, 506-10, 557-66, Aug., Sept., Oct. 1911, Vol. XL, pp. 35-41, 100-6, Jan. - Feb. 1912, Vol. XLII, pp. 620-8, Nov. 1914, and Vol. XLIII, pp. 213-23, April 1915.

- Centenary of Aubrey de Vere, in The Irish Book Lover, Vol. V, pp. 113-115, February 1914.

- Seven notebooks containing reflections and musings of Aubrey de Vere on religious and other matters 1842-1849 held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Personal diary of Aubrey De Vere, of which only a few pages have been used, 1899, held as NLI MS [Archive]: .

- A few notes of letters and books sent and received by Aubrey De Vere 1899 - held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Four small note-books of personal memoranda, addresses, &c. by Aubrey De Vere, 19th c. held as NLI MS [Archive].

- The human affections in the early Christian time, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. I, pp. 79-83, August 1873.

- Legends of the Saxon saints by Aubrey De Vere, reviewed, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. VII, pp. 497-501, September 1879.

- An episode in the history of Mitchelstown. From “Recollections of Aubrey De Vere”, by J. B., in Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, Ser. 2, Vol. XI, pp. 184-186 1905.

- The Irish poems of Mr. Aubrey de Vere, by Richard Paul Carton, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXVI, pp. 569-588, November 1898.

- Two new books of poems: “The Sisters of Innisfail and Other Poems” by Aubrey de Vere and “Shakespere’s Curse and Other Poems” reviewed., in The Dublin University Magazine: A Literary and Political Journal, Vol. LVIII, pp. 345-350, September 1861.

- To Aubrey de Vere: a poem beginning “Long have the Muses loved thee: round thy brow”, byWilfred Meynell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. IV, p. 255, April 1876.

- St. Thomas of Canterbury: A dramatic poem by Aubrey de Vere, reviewed by P. F., in The Irish Monthly, Vol. V, pp. 85-93, January 1877.

- Aubrey de Vere on Sir Samuel Ferguson, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. IV, pp. 224-226, April 1887.

- “Aubrey de Vere: a review of “Recollections of Aubrey de Vere”, by C. J. Griffin, in The New Ireland Review, Vol. VIII, pp. 205-211, December 1897.

- ”Aubrey de Vere, by Helen Grace Smith, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXVII, pp. 64-71, February 1899.

- Aubrey de Vere and his “legends of the Saxon saints”, by W. P. S., in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XLII, pp. 450-456, August 1914.

- Query from J. P. Fleming, London, as to Aubrey de Vere’s paraphrase of Psalm 137, in The Irish Book Lover, Vol. XXIV, p. 42, March - April 1936.

- Presscuttings relating to Aubrey de Vere.held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Mr. de Vere’s Alexander the Great reviewed by Rev. J[ohn] S[tephen] Conmee S.J., in The Irish Monthly, Vol. II, pp. 664-668, November 1874.

- Aubrey De Vere, by Rev. Matthew Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. V, pp. 645-656, October 1877.

- De Vere’s legends of Ireland’s heroic age, being a review of “The Foray of Queen Meave” and other legends of Ireland’s Heroic age by Aubrey de Vere, by Rev. Matthew Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. X, pp. 722-733, November 1882.

- De Vere’s “Legends and records of the Church and Empire”, by John O’Hagan, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVI, pp. 25-38, January 1888.

- Mr. Aubrey de Vere’s new volume, by Rev. Patrick Augustine Sheehan, in The Irsh monthly, Vol. XXII, pp. 126-138, March 1894.

- Maynooth’s centenary: a poem beginning “I heard a voice and turned me. From above”, by Aubrey de Vere, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXIII, p. 433, August 1895.

- A poet’s month of May: an article on Aubrey de Vere’s May Carols, by Rev. George O’Neill, in The New Ireland Review, Vol. XV, pp. 129-145, May 1901.

- Aubrey de Vere, by Rev. Matthew Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXX, pp. 122-124, March 1902.

- Aubrey de Vere by M. Rev., M. McPolin, in The New Ireland Review, Vol. XXXI, pp. 268-282, July 1909.

- The centenary of Aubrey de Vere, by Rev. George O’Neill, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XLII, pp. 237-244, May 1914.

- Aubrey de Vere and his circle, by Maurice Leahy, in The Ireland-American Review, Vol. I, No. 3, pp. 307-316, [1940].

- A copy book of 1731, the property of Vere Hunt, grandfather of Aubrey de Vere, the poet, by R. W. J., in North Munster Antiquarian Journal, Vol. III, p. 123 1942.

- Autograph letters between Sir William Rowan Hamilton and Aubrey de Vere, dealing with literary and scientific matters 1831-63 - held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Six original letters and two “photostat” copies of letters of Aubrey de Vere on literary topics written to various persons including Lady Ferguson and Katharine Tynan, - held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Latter day poets: De Vere, Tennyson, The virgin widow, by A, in The Dublin University Magazine: A Literary and Political Journal, Vol. XXXVI, pp. 209-224, August 1850.

- Rainy day with Tennyson and our poets (including Aubrey de Vere, Richard Chenevix Trench etc.), in The Dublin University Magazine: A Literary and Political Journal, Vol. LV, pp. 53-65, January 1860.

- “In memory of the late Earl of Dunraven: a poem beginning: “Once more I pace thy pillared halls”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. II, p. 22, January 1874.

- Sir Aubrey de Vere’s “March Tudor” and Mr. Tennyson’s “Queen Mary”, by John O’Hagan, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. IV, pp. 572-587, September 1876.

- Poets I have known - III: Aubrey de Vere, by Rev. Matthew by Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXXI, pp. 121-135, March 1903.

- Journals of W. J. O’Neill Daunt from Sept. 12 1842 to March 9 1888. - With an appendix containing copies of letters to Daunt from various persons including Smith O’Brien, [...] - held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Letters of some interest now for the first time printed by Rev. Matthew Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXXVI, pp. 121-6, 255-60, 361-6, 474-7, 649-57, March to Nov. 1908; Vol. XXXVII, pp. 169-72, 341-6, March, June 1909.

- Sonnets on colonisation beginning “England, thy sinful past has found thee out”.by De Vere, Aubrey Published 1849.

- The Dublin University magazine: a literary and political journal, Vol. XXXIV, p. 110, p. 242, July, August 1849.

- Sonnets: on the consecration of Ireland to the Sacred Heart, Passion Sunday, 1873. Poem beginning “Lift up Thy gates, triumphant Heart Eterne”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. I, p. 10, July 1873.

- Lines, being a poem beginning “Since last with thee, my guide unseen”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. I, p. 129, September 1873.

- ”How came there sin to world so fair”: a poem beginning with same line, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. I, p. 361, December 1873.

- Pastor Aeternus: a poem beginning “I scaled the hills. No murky blot”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. II, p. 219, April 1874.

- Two new “May Carols”. “O cowslips sweetening lawn and vale”. “The golden day is dead at last”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. II, p. 300, May 1874.

- The Daughters of Mary. A May Carol beginning “From sin - but not alone from sin - ”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. III, p. 338, May 1875.

- Sonnet on a fresh outbreak of detraction against the Church: “Revolted province of the Church of God” in The Irish Monthly, Vol. III, p. 470, July 1875.

- Sonnet: on the laying of the Foundation Stone of the new Church of St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth beginning “Not vain the faith and patience of the sainte.” in The Irish Monthly, Vol. IV, pp. 14-15, December 1875.

- Literary notices: “The infant burial and other poems” by Aubrey de Vere reviewed, in The Dublin University Magazine: A Literary and Political Journal, Vol. LXXXVII, pp. 124-128, January 1876.

- Fountain’s Abbey: a poem beginning “The hand of Time is heavy: yet how soft”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. V, p. 17, December 1876.

- The dirge of Desmond: a poem beginning “Rush dark dirge, o’er hills of Erin”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. V, pp. 314-315, May 1877.

- Saint Joseph: a poem beginning “Ho ye that toil and ye that spin”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. VI, pp. 131-133, March 1878.

- Sonnets in memory of Sir William Hamilton Rowan beginning “Friend of past years, the holy and the blest”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. VIII, p. 674, December 1880.

- Filia Mariae: a poem beginning “One thought alone ’mid all this sea”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. IX, p. 278, May 1881.

- Genius and sanctity: a couplet beginning “How high he soars”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XI, p. 74, February 1883.

- Death: a poem beginning “Why shrink from Death? In ancient days we know”, The Irish Monthly, Vol. XI, p. 100, February 1883.

- Age: a poem beginning “Old age! The sound is harsh and grates”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XI, p. 162, March 1883.

- An autumn song: beginning “O fading flower, O faded leaf”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XI, p. 330, June 1883.

- Oisin the bard and St. Patrick: a poem beginning “Patrick, ‘tis right thy house should roof”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XII, pp. 10-12, January 1884.

- The dethronement of the Pope: a poem beginning “No, Italy, that deed was never thine”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVI, p. 409, July 1888.

- St. Peter’s chains: a review of his sonnets on the Italian Revolution, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVI, pp. 607-615, October 1888.

- Montalembert and De Merode: a sonnet beginning “Montalembert! De Merode! Linked were ye”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVI, p. 677, November 1888.

- St. Chrysostom’s return from Exile: a poem beginning “Sad is the music through the midnight seas”, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVII, p. 200, April 1889.

- Sonnets: I. Mary, Queen of Scots: beginning “Strong land by Wallace trod and Bruce: brave land”. II. The Prince of Wales tribute to Fr. Damien: beginning “ ‘twas just! Fanatic’ [by Aubrey de Vere], in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVII, p. 640, December 1889.

- Unpublished letters of Aubrey de Vere, by Rev. Matthew Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXXIX, pp. 421-9, 506-10, 557-66, Aug., Sept., Oct. 1911, Vol. XL, pp. 35-41, 100-6, Jan. - Feb. 1912, Vol. XLII, pp. 620-8, Nov. 1914, and Vol. XLIII, pp. 213-23, April 1915.

- Centenary of Aubrey de Vere, in The Irish Book Lover, Vol. V, pp. 113-115, February 1914.

- Seven notebooks containing reflections and musings of Aubrey de Vere on religious and other matters 1842-1849 held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Personal diary of Aubrey De Vere, of which only a few pages have been used, 1899, held as NLI MS [Archive]: .

- A few notes of letters and books sent and received by Aubrey De Vere 1899 - held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Four small note-books of personal memoranda, addresses, &c. by Aubrey De Vere, 19th c. held as NLI MS [Archive].

- The human affections in the early Christian time, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. I, pp. 79-83, August 1873.

- Legends of the Saxon saints by Aubrey De Vere, reviewed, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. VII, pp. 497-501, September 1879.

- An episode in the history of Mitchelstown. From “Recollections of Aubrey De Vere”, by J. B., in Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, Ser. 2, Vol. XI, pp. 184-186 1905.

- The Irish poems of Mr. Aubrey de Vere, by Richard Paul Carton, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXVI, pp. 569-588, November 1898.

- Two new books of poems: “The Sisters of Innisfail and Other Poems” by Aubrey de Vere and “Shakespere’s Curse and Other Poems” reviewed., in The Dublin University Magazine: A Literary and Political Journal, Vol. LVIII, pp. 345-350, September 1861.

- To Aubrey de Vere: a poem beginning “Long have the Muses loved thee: round thy brow”, byWilfred Meynell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. IV, p. 255, April 1876.

- St. Thomas of Canterbury: A dramatic poem by Aubrey de Vere, reviewed by P. F., in The Irish Monthly, Vol. V, pp. 85-93, January 1877.

- Aubrey de Vere on Sir Samuel Ferguson, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. IV, pp. 224-226, April 1887.

- “Aubrey de Vere: a review of “Recollections of Aubrey de Vere”, by C. J. Griffin, in The New Ireland Review, Vol. VIII, pp. 205-211, December 1897.

- ”Aubrey de Vere, by Helen Grace Smith, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXVII, pp. 64-71, February 1899.

- Aubrey de Vere and his “legends of the Saxon saints”, by W. P. S., in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XLII, pp. 450-456, August 1914.

- Query from J. P. Fleming, London, as to Aubrey de Vere’s paraphrase of Psalm 137, in The Irish Book Lover, Vol. XXIV, p. 42, March - April 1936.

- Presscuttings relating to Aubrey de Vere.held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Mr. de Vere’s Alexander the Great reviewed by Rev. J[ohn] S[tephen] Conmee S.J., in The Irish Monthly, Vol. II, pp. 664-668, November 1874.

- Aubrey De Vere, by Rev. Matthew Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. V, pp. 645-656, October 1877.

- De Vere’s legends of Ireland’s heroic age, being a review of “The Foray of Queen Meave” and other legends of Ireland’s Heroic age by Aubrey de Vere, by Rev. Matthew Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. X, pp. 722-733, November 1882.

- De Vere’s “Legends and records of the Church and Empire”, by John O’Hagan, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XVI, pp. 25-38, January 1888.

- Mr. Aubrey de Vere’s new volume, by Rev. Patrick Augustine Sheehan, in The Irsh monthly, Vol. XXII, pp. 126-138, March 1894.

- Maynooth’s centenary: a poem beginning “I heard a voice and turned me. From above”, by Aubrey de Vere, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXIII, p. 433, August 1895.

- A poet’s month of May: an article on Aubrey de Vere’s May Carols, by Rev. George O’Neill, in The New Ireland Review, Vol. XV, pp. 129-145, May 1901.

- Aubrey de Vere, by Rev. Matthew Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXX, pp. 122-124, March 1902.

- Aubrey de Vere by M. Rev., M. McPolin, in The New Ireland Review, Vol. XXXI, pp. 268-282, July 1909.

- The centenary of Aubrey de Vere, by Rev. George O’Neill, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XLII, pp. 237-244, May 1914.

- Aubrey de Vere and his circle, by Maurice Leahy, in The Ireland-American Review, Vol. I, No. 3, pp. 307-316, [1940].

- A copy book of 1731, the property of Vere Hunt, grandfather of Aubrey de Vere, the poet, by R. W. J., in North Munster Antiquarian Journal, Vol. III, p. 123 1942.

- Autograph letters between Sir William Rowan Hamilton and Aubrey de Vere, dealing with literary and scientific matters 1831-63 - held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Six original letters and two “photostat” copies of letters of Aubrey de Vere on literary topics written to various persons including Lady Ferguson and Katharine Tynan, - held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Latter day poets: De Vere, Tennyson, The virgin widow, by A, in The Dublin University Magazine: A Literary and Political Journal, Vol. XXXVI, pp. 209-224, August 1850.

- Rainy day with Tennyson and our poets (including Aubrey de Vere, Richard Chenevix Trench etc.), in The Dublin University Magazine: A Literary and Political Journal, Vol. LV, pp. 53-65, January 1860.

- “;In memory of the late Earl of Dunraven: a poem beginning: ‘Once more I pace thy pillared halls“, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. II, p. 22, January 1874.

- Sir Aubrey de Vere’s “March Tudor” and Mr. Tennyson’s “Queen Mary”, by John O’Hagan, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. IV, pp. 572-587, September 1876.

- Poets I have known - III: Aubrey de Vere, by Rev. Matthew by Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXXI, pp. 121-135, March 1903.

- Journals of W. J. O’Neill Daunt from Sept. 12 1842 to March 9 1888. - With an appendix containing copies of letters to Daunt from various persons including Smith O’Brien, [...] - held as NLI MS [Archive].

- Letters of some interest now for the first time printed by Rev. Matthew Russell, in The Irish Monthly, Vol. XXXVI, pp. 121-6, 255-60, 361-6, 474-7, 649-57, March to Nov. 1908; Vol. XXXVII, pp. 169-72, 341-6, March, June 1909.

|

| § |

| Available at National Library of Ireland [NLI] - Electronic Catalgue > Aubrey Thomas de Vere - online; accessed 20.06.2019. |

|

|

| Anthologies |

- Justin McCarthy, ed., Irish Literature (1904), gives extracts from English Rule and Irish Misdeeds [see extract], and also 8 songs.

- Arthur Quiller Couch, ed., Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1918 (new edn. 1929), p.742.

- Alfred Williams, Poets and Poetry of Ireland, with Historical and Critical Essays and Notes [sic] (Boston: James R. Osgood & Company 1881) [gives this account: ‘an Irish poet representing the highest type of the modern Catholic spirit, and of rare and spiritual refinement, is Aubrey Thomas de Vere ... third son of Aubrey De Vere ... .’ (p.351)].

- Geoffrey Taylor, ed., Irish Poets of the Nineteenth Century (London 1951), contains a biographical sketch and a selection of his poetry.

|

|

Brian McKenna, Irish Literature, 1800-1875: A Guide to Information Sources (Detroit: Gale Research Co. 1978), cites centenary notices, in Irish Booklover, 5. (1914), and Irish Monthly, 42 (1914); biog., in The Nation (15 Dec. 1888). Recollections of Aubrey de Vere, autobiog. (NY 1897). J

Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe: 1980), Vol. 2, gives bio-data: ‘converted to Catholicism in 1851; one of the major links between Romanticism and the Celtic Renaissance of the end of the century ... a disciple of Wordsworth, closely acquainted with Coleridge’s daughter, champion of Tennyson and Sir Henry Taylor.’; lists The Waldenses, or the Fall of Rora, a lyrical sketch (Oxford 1842); The Search After Proserpine (Oxford, 1843); other works as listed in Belfast Central Public Library and FDA, but including Alexander the Great, a dramatic poem (1874); St Thomas of Canterbury, a dramatic poem (1876); Antar & Zara [repr. earlier poems] (1876); Legends and Records of the Church and the Empire (1887); St Peter’s Chains (1888).

Brian Cleeve & Ann Brady, A Dictionary of Irish Writers (Dublin: Lilliput 1985), ed. TCD, convert. Catholic, 1851; large amount of poetry incl. The Foray of Queen Maeve (1882); Recollections ([NY & London 1897) [extensively cited in Robert Welch, op. cit., 1980].

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, selects The Sisters, Inisfail and Other Poems, ‘In Ruin Reconciled’, ‘The Years of Sorrow’, ‘Irish Colonization, 1848’ [55-57]; ‘are de Vere and Griffin and Mangan to be nothing’ (Rolleston, 1901) [973]; quoted by James (in Erin’s Hope, pamphlet 1896) Connolly as well illustrat[ing]’ the ‘“new race” of exploiters’ which arose in Ireland after the invasion and the primtive socialism of ancient Gaelic society [‘The chiefs of the Gael were the people embodied; The chiefs were the blossoms, the people the root. / Their conquerors, the Normans, high-souled and high-blooded, / Grew Irish at last from the scalp to the foot. / And ye, ye are hirlings and satraps, not nobles - Your slaves they detest you, your masters, they scorn. the river lies on, but the sun-painted bubbles / Pass quickly, to the rapids incessantly borne’ (“The New Race”, in the Poetic Works, 1897, Vol. V, p.137), 987 [but see bio-bibl. infra]; A.T. De Vere cited by Corkery as one of those without the ‘Irish accent of Ferguson’ (Corkery, 1931, p.113) [990].

BIOG [FDA]: 3rd son of Sir Aubrey; ed. TCD; friend of many Victorian sages and championed Tennyson; became Catholic in 1851; unmarried; d. Curragh Chase, 1902. Note, bibl. omits Waldenses, Proserpina and Poems (1855).

Library Catalogues

Belfast Central Public Library holds 12 titles by A. de Vere [that is, both of the name], viz., English Misrule and Irish Misdeeds [1848]; Essays Chiefly Literary and Ethical; Essays Chiefly on Poetry; The Fall of Rora; The Infant Bridal and other Poems; Irish Odes; The Legends of St. Patrick [1889]; [?The Month of May]; Poems (1855); Poems, a Selection (1890); Poetical Works (1884); The Poetical Works of Aubrey de Vere, 2 vols. (1895); The Sisters, Inisfail, and other poems; Sonnets. ALSO Biog., J. P. Gunning, Aubrey de Vere (1902); Wilfrid Ward, Aubrey de Vere, A Memoir (1904).

Hyland Catalogue (Jan. 1996) lists Legends of the Saxon Saints (London 1879), signed pres. copy to his niece Alice O’Brien, with ded. stanza beginning ‘Smiles are the wrinkles of our youth’.]

[ top ]

Quotations

Poetry

| Legends of St. Patrick (1872) |

Patrick on the Druids [viz., Irish filí or bards]: ‘Darksome is their life: / Darksome their pride, their love, their joys, their hopes; / Darksome, though gleams of happier lore they have, / Their light! Seest thou the forest floor, and o’er it, / The ivy’s flash - earth-light? Such light is theirs: / By such no man walks!’ (Legends of St. Patrick, 1889, p. 105). |

St. Patrick to Oisin: ‘Old man, though hearest our Christian hymns; / Such strains though hadst never head -/ “Thou liest, thou priest! For in Letter Lee wood / I have listened its famed blackbird!’ (from The Legends of St. Patrick, 1872; cited in Alannah Hopkins, Living Legend of St. Patrick, 1989, with the remark, ‘de Vere manages to emphasise the attractions of Christianity without denigrating the paganism of the heroes of old’; p.148-49.) |

§

|

“The ‘Washing Of The Feet,’ on Holy Thursday, in St. Peter’s” |

Once more the temple-gates lie open wide:

Onward, once more,

Advance the Faithful, mounting like a tide

That climbs the shore.

What seek they? Blank the altars stand today,

As tombstones bare:

Christ of his raiment was despoiled; and they

His livery wear.

Today the puissant and the proud have heard

The ‘mandate new’:

That which He did, their Master and their Lord,

They also do.

Today the mitred foreheads, and the crowned,

In meekness bend:

New tasks today the sceptred hands have found;

The poor they tend.

Today those feet which tread in lowliest ways,

Yet follow Christ,

Are by the secular lords of power and praise

Both washed and kissed.

Hail, ordinance sage of hoar antiquity,

Which She retains,

That Church who teaches man how meek should be

The head that reigns!

|

| See Poem Hunter - online; accessed 20.06.2019. |

§

| “The Three Woes’ |

That angel whose charge was Eiré sang thus, o&’er the dark Isle winging;

By a virgin his song was heard at a tempest&’s ruinous close:

“Three golden ages God gave while your tender green blade was springing;

Faith&’s earliest harvest is reaped. To-day God sends you three woes.

“For ages three without laws ye shall flee as beasts in the forest;

For an age and a half age faith shall bring, not peace, but a sword;

Then laws shall rend you, like eagles sharp-fanged, of your scourges the sorest;

When these three woes are past, look up, for your hope is restored.

“The times of your woes shall be twice the time of your foregone glory;

But fourfold at last shall lie the grain on your granary floor.”

The seas in vapour shall flee, and in ashes the mountains hoary;

Let God do that which He wills. Let his servants endure and adore!”

|

| See Poem Hunter - online; accessed 20.06.2019. |

§

| “Roisín Dubh” |

O who are thou with that queenly brow

And uncrowned head?

And why is the vest that binds thy breast,

O’er the heart, blood-red?

Like a rose-bud in June that spot at noon,

A rose-bud weak;

But it deepens and grows like a July rose:

Death-pale thy cheek.

“The babes I fed at my foot lay dead;

I saw them die;

In Ramah a blast went wailing past;

It was Rachel’s cry.

But I stand sublime on the shores of Time,

And I pour mine ode,

As Miriam sang to the cymbals’ clang,

On the wind to God.

“Once more at my feasts my bards and priests

Shall sit and eat:

And the Shepherd whose sheep are on every steep

Shall bless my meat;

Oh, sweet, men say, is the song by day,

And the feast by night;

But on poisons I thrive, and in death survive

Through ghostly night.”

|

| See Poem Hunter - online; accessed 20.06.2019. |

[ top ]

Prose

|

“How To Govern Ireland” (from English Misrule and Irish Misdeeds, 1848) |

| |

|

I do not affirm, or imply, that England possesses less of moral truth than other nations which make it less their boast. I state simply that it does not bear that proportion which it ought to her verbal truth, and therefore that she has nothing to boast of in this particular. Does a truthful nation, when called on to act, allow the gates of new and serviceable knowledge to be blocked up by a litter of wilful and sottish prejudices? Is it a truthful act to judge where you have no materials, and to condemn where you pause not to judge? You often depict with minuteness and consistency the character of an Irish peasant or proprietor. As long as a class of men seems to you stamped with one common image, conclude that you see it but from a distance, and as a mask. On closer inspection you would trace the diversities of individuality. You know no more of the Irish peasant or proprietor than the former knows of you, and you as little care to know them.

I do not call the Irish the finest peasantry in the world, although, if their characters were equal to their dispositions, they might, perhaps, justly be so termed; but I have no reason to believe that they are inferior, in aught but happiness and a sphere for goodness, to the same class in England. The Irish peasant, sir, is rich in virtues, which yon know not of because you know only the worst class of Irish, and only hear of the rest when they are found wanting under the severest temptations. Amongst his virtues are many which, perhaps, no familiarity would enable you to recognize. I speak of the Irish peasant as a man and as a Christian, not as a citizen merely. There is a difference [855] between public and individual virtues: to the latter class belong many which, by their own nature, remain exempt from applause or material reward; and among the former there are commonly accounted several vices. Self-confidence, ruthlessness, and greediness - these are not virtues; but notwithstandiog, when associated with a manliness as willing to suffer as to inflict pain, and an industry if not disinterested yet dutiful, these defects may help to swell the prosperity of a nation, as long as she swims with the tide. Many of the crowning virtues of personal character may be possessed where several fundamental virtues of civil society are wanting.

The Irish peasant has a patience under real sufferings quite as signal as his impatience under imaginary grievances; and in spite of a complexional conceit not uncommon, he has a moral humility that does not help him to make his way. He possesses a reverence that will not be repulsed; a gratitude that sometimes excites our remorse; a refinement of sensibility, and even of tact, which re-minds you that many who toil for bread are the descendants of those who once sat in high places; aspirations that fly above the March of national greatness; a faith and charity not common in the modern world; an acknowledged exemption from sensual habits, both those that pass by that name, and those that invent fine names for themselves; and an extraordinary fidelity to the ties of household and kindred, the more remarkable from being united with a versatile intellect, a temperament mercurial as well as ardent, and an ever salient imagination. These virtues are not inconsistent with grave faults, but they are virtue of the first order. I will only add, that if England has wit enough to make these virtues her friends, she will have conciliated the affections of a people the least self-loving in the world, and the services of a people amongst whom, in the midst of much light folly, there is enough of indolent ability to direct the whole councils of England, and of three or four kingdoms beside - provided only that Ire-land be not of the number.

I have already recommended you to study the Irish if yon would learn how to govern Ireland ; and though I cannot undertake to be your master, yet I would seriously advise you not to allow yourself to dwell only on the worst [866] side of the national character. If you laugh at an Irish peasant’s helplessness, remember that be is as willing to help a neighbour as to ask aid; and that he has a remarkable faculty for doing all business not his own. If yon think him deficient in steadiness under average circumstances, remember that be possesses extraordinary resource and powers of adaption. If yon think him easily deluded, remember that the same quick and fine temperament which makes him catch every infection or humour in the air renders him equally accessible to all good influences; of which the recent temperance movement is the most remarkable example exhibited by any modern nation.

You accuse the Irish peasant of want of gravity: one reason of this characteristic is, that with him imagination and fancy are faculties not working by themselves, but diffused through the whole being; and remember that, if tbey favour enthusiasm, so on the other hand they protect from fanaticism. If you speak of his occasional depression and weakness, you should know that Irish strength does not consist in robustness, but in elasticity. If you complain of his want of ambition, remember that this often proceeds from the genuine independence of a mind and temperament which possesses too many resources in themselves to be dependent on outward position; and do not forget that much of the boasted progress of England results from no more exalted a cause than from an uncomfortable habit of body, not easy when at rest. If you think him deficient in a sound judgment, ask whether his mental faculties may not be eminently of a subtle and metaphysical character, and whether such are not generally disconnected from a perfect practical judgment.

You are amused because he commits blunders: ask whether he may not possibly think wrong twice as often as the English peasant, and yet think right five times as often, since he thinks ten times as much, and has a reason for everything that he does. You call him idle: ask whether he does not possess a facility and readiness not usually united with painstaking qualities; and remember that, when fairly tried, he by no means wants industry, though he is deficient in energy. You think htm addicted to fancy rather than realities: poverty is a great feeder of enthusiasm. You object to his levity: competence is [867] a sustainer of respectability; and many a man is steadied by the weight of the cash in his pocket. You call him wrong-headed: ask whether the state of things around him, the bequest of past misgovernment, is not so wrong as to puzzle even the solid sense of many an English statesman, not inexperienced in affairs; and whether the good intentions and the actions of those who would benefit the Irish peasant are not sometimes, even now, so strangely at cross purposes as to make the quiet acceptance of the boon no easy task. Yon think him slow to follow your sensible precepts: remember that the Irish are imitative, and that the imitative have no great predilection for the didactic vein: and do not forget that for a considerable time your example was less edifying than your present precepts. You affirm that no one requires discipline so much; remember that none repays it so well; and that, as to the converse need, there is no one who requires so little aid to second his intellectual development. The respect of his neighbour, you say, is what he hardly seeks: remember how often he wins his love, and even admiration, without seeking it. You think that he hangs loosely by his opinions: ask whether he is not devoted to his attachments. He seems to you inconsistent in action: reflect whether extreme versatility of mind and consistency of conduct are qualities often united in one man. You complain of the disposition of the Irish to collect in mobs: ask whether, if you can once gain the ear of an Irish mob, it is not far more accessible to reason than an English one.

I have addressed myself to Irish mobs under various circumstances in the last two years, and encountered none that was not amenable. Ask also whether in most countries the lower orders have not enough to do, as well as enough to eat in the day, and consequently a disposition to sleep at night. If half your English population had only to walk about and form opinions, how do you think you would get on? You say that the Irish have no love of fair play, and that three men of one faction will fall on one man of another: ask those who reflect as well as observe, whether this proceeds wholly from want of fair play or from other causes beside. Ask whether in Ireland the common sentiment of race, kindred, or clan, does not prevail with an intensity not elsewhere united with a perfect appreciation [858] of responsibilities and immanities; and whether an Irish beggar will not give you as hearty a blessing in return for a halfpenny bestowed on another of his order as on himself. Sympathy includes a servile element, and servile sympathy will always lead to injustice; thus I have heard a hundred members of Parliament (and of party) drown in one cry, like that of a well-managed pack, the voice of some member whom they disapproved, and whom probably they considered less as a man than as a limb of a bated enemy. Sympathy, however, often ministers to justice also, as you find on asking an Irish gentlemen whether he has not often been astonished at that refinement of fair play with which an Irish peasant makes allowances for the difficulties of some great neighbour, whose aid is his only hope.

|

| |

| [Given in Irish Literature, gen. ed Justin McCarthy (Washington: Catholic University of America 1904), pp.855-58; available at Internet Archive - online.] |

[ top ]

Notes

|

Aubrey Thomas de Vere was a friend and correspondent of Sir William Rowan Hamilton (1805-65). For further, see under Hamilton - infra. |

Tennyson’s poem ‘The splendour falls on castle walls’ is the third of the songs later added to The Princess (1847), with the refrain, ‘Blow, bugle, blow, set the wild echoes flying, / Blow, bugle; answer, echoes, dying, dying, dying.’ Tennyson’s note says, ‘Written after hearing the echoes at Killarney in 1848. When I was there I head a bugle blown beneath the “Eagle’s Nest” [Keimaneige], and eight distinct echoes’ (See Christopher Ricks, ed., Poems of Tennyson, 1987, Vol. 2, pp.230-31; information supplied by Jack Kolb, Dept. of English, UCLA, via Diaspora e-list in 2009).