Life

| 1943- ; b. Achill, Co. Mayo; ed. Mungret and UCD (BA, Eng. & French; MA, English & American Lit. HDip.Ed); trained for priesthood but worked as teacher instead; refounded Poetry Ireland and Poetry Ireland Review, 1979; first published by Profile in Clondalkin, Co. Dublin; conducted hand-printing press from 1972; successively fnd.-director of Aquila, St. Bueno’s, and Dedalus, 1985, with an initial address at Cypress Downs; fnd. Poetry Ireland Review, 1979; undertook publication of Kinsella’s Peppercannister series under the Dedalus imprint; ed. Dedalus Irish Poets (1992), collecting ‘the best of the original poetry published by The Dedalus since its inception’; |

| ed. the journal Tracks; issued Christ With Urban Fox (1997), winner of O’Shaugnessy Prize for Irish Poetry in 1998; also In the Name of the Wolf (1999), concerning the visitations of a werewolf in Co. Mayo which seem to connected with the condition lupus suffered by Patricia O’Higgins; issued The Coffin Master and Other Stories (2000); winner of £7,875 Marten Toonder Award, 2002; issued Undertow (2002), a novel of the western isles; new collection, Manhandling the Deity and a trans. of Phillipe Jones, Breath of Words (both 2003); issued The Instrument of Art (2005); |

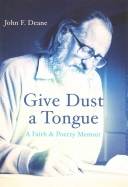

| winner of Tom McNulty Poem Award, June 2004; issued The Heather Field and Other Stories (2007); also From the Marrowbone (2008), essays and poetry on human spirituality; received Golden Key of Smederevo Award, previously given to Yves Bonnefoy, et al.; his poems trans. into Serbian by Dragan Dragojlovic (forthcoming, Oct. 2011); issued Semibreve (May 2015), incorporating elegies for a lost brother who was a Jesuit in California - shortlisted for Irish Times best collection prize, 2016; also Give Dust a Tongue (2015), a literary and spiritual memoir; he has lecture on Faith in Poetry at Loyola Univ., Chicago. OCIL |

[ top ]

Works| Poetry |

|

| Short Fiction |

|

|

[ top ] |

| Novels |

|

| Miscellaneous |

| Also: With Whom Did I Share the Crystal?, by John Jordan (Dublin: John F. Deane 1972), in a limited handprinted edition. |

| Memoir |

|

| Contributions incl. |

|

Incl. in Five Irish poets, ed. David Lampe & Dennis Maloney, with an introduction by Lampe and a preface by Thomas Kinsella (Dublin: Dedalus; Fredonia NY: White Pine Press 1990), 136p. [with Padraig J. Daly, Richard Kell, Dennis O’Driscoll, Macdara Woods]. |

| [ top ] |

Bibliographical details

The Dedalus Irish Poets, ed. J. F. Deane (Dublin: Dedalus Press 1992) [q.pp.], contains poems by Robert Greacen; Conleth Ellis; John F. Deane; Patrick Deeley; Gerard Smyth; Richard Kell; Macdara Woods; Hugh Maxton; Tom MacIntyre; Dennis O’Driscoll; Charlie Donnelly; Patrick O’Brien; Padraig J. Daly; Valentine Iremonger; Denis Devlin; Pat Boran; Ciaran O’Driscoll; John Jordan; John Ennis; Leland Bardwell; Robert Welch; Paul Murray [Newcastle, Co. Down]; Brian Coffey; Thomas McCarthy.Irish Poetry of Faith and Doubt, ed. John F. Deane (Dublin: Wolfhound Press 1991), 191pp., incls. poems by Cecil Frances Alexander, Patrick Kavanagh and Padraic Fallon, et al.; also Seamus Heaney, “Docker“, “Poor Woman in a City Church”, “In Gallarus Oratory”, “The Other Side”, “In Illo Tempore” [155-58]; Derek Mahon, “Nostaglias” [159], .. &c.

Give Dust a Tongue (2015): ‘A memoir that views the spiritual developments of an internationally acclaimed poet, from the strict Roman Catholic of his upbringing on Achill Island, through years spent in a Spiritan Seminary studying for the priesthood, a marriage and the death of a young wife, through the establishment of Poetry Ireland, the National Poetry Society, and the development of his own poetic career, the study of such faith poets as George Herbert and Gerard Manley Hopkins, to his present faith in Christ as the centre of hope and evolution. The book uses many of Deane’s best and best-loved poems to help chart this development and works towards the origins and completion of a sequence of poems that face directly the question Christ asked: Who do you say that I am? Deane’s answer is in a sequence of poems, published here for the first time ... The route to a contemporary Christian faith takes in memories of his time on Achill Island, in the novitiate in Tipperary and the seminary in Kimmage, Dublin, as well as his encounter with the work of Teilhard de Chardin ... and the poetry of the Nobel prize-winning Swedish writer, Tomas Tranströmer ... The work also examines the continuation of faith after the death of Deane’s brother, Declan, who had become a Jesuit and died in Pleasant Hill in California ... The whole offers one person’s pursuit of faith through a personal response to the name and nature of Jesus Christ, a faith that would be possible, even essential, in this age of un-faith and economic determinacy’ (Columbia Press notice; available at Google Books - online.

[ top ]

Criticism

|

[ top ]

Commentary

H. M. Buckley, review of Free Range, in Books Ireland (April 1995), p.81, notes that the underlying theme is the force of the supernatural, the spirit, that which we do not see or understand. cites title story with its terrible ending; collection speaks less of free spirits than of misfits, of loneliness, whether in suburbia or western seaboard were several are set titles as above]; also One Man’s Place (Dublin: Poolbeg 1994), 229pp., novel; Matthew Blake, father of narrator David, is trained in use of guns during War of Independence and encouraged in hatred by Christian Brothers; he finds violence perpetuated in a bullying episode at the school where he is principal; involved in assassination attempt against de Valera; condemns violence.

John Kenny, review of In the Name of the Wolf [with novel by Colm O’Gaora], in Irish Times (27 March 1999), [q.p.]; points out unintentional comedy in references to ‘the abominable bogman’, and conventional horror-elements in ‘something approached across the soft sucking surfaces of the moor’, and instances the silver bullet in use in the final hunt scene; calls it all ‘convincingly unreal stuff’.

Sue Leonard, review of In the Name of the Wolf, in Books Ireland (Summer 1999), p.185; commended for its originality in many phrases; quotes the schoolteacher who explains, ‘Theriophobia. Fear of the beast. Fear of ourselves, fear of what we know is wicked in our hearts.’

Peter Sirr, review of John F. Deane, Toccata and Fugue: New and Selected Poems (Carcanet), 95pp., in The Irish Times (2 Sept. 2000), citing “The Fox God“, “The Real Presence“, “Reynolds“ and “Fogue“, the latter a personal poem addressing wife, father, daughter. Sirr remarks, ‘many of Deane’s poems utter the same cry to the God who may be there, whose absence is more keenly felt than his presence, whom the poems argue with and for, balancing anger with acceptance and love. John F. Deane is in this sense a religious poet’ though his poetry ‘doesn’t offer any blind acts of faith’; quotes ‘perhaps God / is the ocean we step out on / through death, into our origins [...]’; ‘The sea surrounds us in the way, we hope, / God’s care surrounds us [...]’; ‘something like Hopkins [...] / who gnawed on the knuckle-bones of words / for sustenance - because God / scorched his bones with nearness [...]’; compares God to an urban fox ‘grown / secretive before our bully-boy modernity’.

Maurice Harmon, review of Undertow, in Books Ireland (Dec. 2002): Harmon writes of a beautifully crafted novel of resonant style (‘the writing is magical’), especially in dealing with nature, but also reflecting a ‘human world where a girl is hidden away in a loft, and sexually abused, where a woman carries the secret of her conception to her dying day, where a Spanish trawler harasses the local fishermen, where Alison a young tinker throws herself off a cliff with her illegitimate child, where there are tears, strokes, TB and at times a deep religious sense.’ (p.311.) The novel moves between the period 1951-52 and 1996-97 in Achill; the central character is Aenghus.

Michael Brett, notice of The Coffin Master and Other Stories (Belfast: Blackstaff), Times Literary Supplement (31 March 2000), p.22: An easeful leave-taking is described “Rituals of Departure” , the opening story [where] an agonised old man relives the passions of his youth before rising from his death bed, stripping away his clothes and disappearing into a dark forest [quotes]: “They found his clothes, shoes, underwear, overcoat, all laid out neatly on the road …” . Brett calls it ‘an exodus from the helpless routine of old age and sickness in the bosom of the rural landscape’ and refers to the ‘delicately rendered Keatsian twilight in which ‘swallows had begun to gather on the wires’ as is typical of Deane’s lyrical stories. Also mentions “A Migrant Bird” , in which a traditional fiddler is ousted by rock music; cites “From a Walled Garden”, in which a woman who has fled from shameful desires into a convent and returns to the world turning her back on ‘demanding, wizened old God … malevolent and self-absorbed and filled with bitterness’ (Deane). Brett remarks that Deane’s Lawrentian symbolism can seemed forced’ and gives an account of the title story in which a virile island huntsman suffers a disfiguring accident, turns coffin-maker, and finally kills himself in an eerie crucifixion, having been falsely accused of murder. Brett concludes, ‘Deane strikes an elegiac and melancholy note throughout, and his portrayal of the conflict between the generations in rural Ireland is reflected in the tonal variations of his writing’ rapidly shifting ‘from quaintness to unexpected violence.

[ top ]

Eileen Battersby, ‘Amid the beauty and the blessed’, review of The Instruments of Art, in The Irish Times (31 Dec. 2005), Weekend: ‘[...] For all the rage - and there is a great deal of refined anger, even theatricality - Deane is committed to justice and many causes, yet in this book he is often at his best when observing the natural world in a mood of mildness, such as in the atmospheric “Old Yellow House”, possibly the most thematically cohesive, self-contained poem of the six sections. / He is a formal, intellectual poet, and one with strong narrative sense - he has published short stories and two novels; his polemic has a message, but not an agenda. [...] Deane’s vision is multi-dimensional but the poems that will linger - and indeed - should earn him a wider audience he deserves, are the gentle memorial and memory pieces mostly from “The Old Yellow House” sequence in which this concerned, deeply serious artist of conscience suspends the declamatory and pauses to remember a moment, an image.’ (See full text, in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, infra.)

Eileen Battersby, [q. title,] interview-article on J. F. Deane in The Irish Times ( 26 Oct. 2002 ), Weekend, p.6., quotes Deane: ‘Poetry is the main thing for me - but anything that won’t become poetry, goes into fiction.’ He particularly enjoys the short-story form, remarking on the perfection of it. His first collection, Free Range, was published in 1994; his second, The Coffin Master and Other Stories (2000), is dominated by the superb title work, a novella of near religious power. [Continues:]‘Characterisation lies at the heart of his storytelling. Of his fiction to date, he points to his third novel, In the Name of the Wolf (1999), as “the first of the novels I stand by. I wrote it as a kind of horror story.” /. It is a dark, sophisticated work. Incited by his first wife’s experience of lupus, the work is not an account of the illness. Instead it is a strange tale in which illness is a metaphor for an invisible evil. True of Deane’s fiction, there is black humour and superb pen portraits of a mixed group of characters including Casimir Conlon, the local butcher, oppressed by his bedridden mother and his doomed sexuality. / Characterisation is also vital to Undertow, a narrative divided between the Achill of the 1950s and the somewhat less brave new world of the island in 1997. “The characters are largely based on real people,” says Deane. Central to it are extremes and contrasts, with the characters all engaged in various bids for freedom and are linked by relentless connections of fate.’ (See full text, in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”,, infra.)

[ top ]

Thomas Dillon Redshaw, ‘“The Dolmen Poets”: Liam Miller and Poetry Publishing in Ireland, 1951-1961’, in Irish University Review: A Journal of Irish Studies (March 2012):‘Nowadays, most readers recognize the English title Poetry Ireland Review - rather than its Gaelic equivalent Iris Eigse Eireann - as the title of a well-designed quarterly that has served Ireland’s contemporary poets and their readers at home and abroad since 1981. ‘Poetry Ireland’, of course, is also the corporate name of the nonprofit organization now located in Kildare Street that publishes the review and sponsors readings and schools programmes throughout the Republic. At the start in 1981, Poetry Ireland Review was edited by John Jordan (1930-88). [13] Both Poetry Ireland and Poetry Ireland Review descend directly from Poetry Ireland, founded and published by John F. Deane between 1978 and 1980. Tom Clyde’s Irish Literary Magazines (2003) gives concise accounts of both magazines as well as of Poetry Ireland, published by Liam Miller. [14] Intended as a quarterly, and also edited by John Jordan, this Poetry Ireland was modelled after Harriet Monroe’s Poetry (Chicago) and reflected the American interests of its editorial board.’ (Q.pp.; available at The Free Library - online; accessed 23-09-2012].

[ top ]

Quotations

“The Return”: ‘I spent such years / striving to sheen my life to a glass / Where God could admire his countenance; // I was one of the tardy generation / who dressed ourselves in black and were left / standing on a wet ledge when the earth shifted; / the hours we chanted, Standing in rows / like cormorants on a wind-blown shore, / shivering together, though at night we could / lay ourselves down in the darkness of obedience; / it was decreation, unlearning, while the world skpipped briskly by our windows.’ (From “The Return” [ded. to Ursula], long poem, in ‘Filíocht Nua: New Poetry’, New Hibernia Review, 1, 1 (Spring 1997), pp.69-77, pp.75-76.

“In Dedication”: ‘Under the trees the fireflies / zip and go out, like galaxies; / our best poems, reaching in from the periphery, / are love poems, achieving calm. // On the road, the cries of a broken rabbit / were pitched high in their unknowing; / our vehicles grind the creatures / down till the child’s tears are for all of us, // dearly beloved, ageing into pain, and for herself, / for what she has discovered early, / beyond this world’s loveliness. Always / after the agitated moments, the search for calm. // Curlews scatter now on a winter field, their calls / small alleluias of survival; / I offer you / poems, here where there is suffering and joy, / evening, and morning, the first day.’ ( The Irish Times , 26 Oct. 2002 , Weekend, p.6.)

| “The Naming of the Bones: London, June 2017” |

|

—Poem of the Week, in The Irish Times (24 June 2017) - online. |

[ top ]

Irish Poetry of Faith and Doubt (Dublin: Wolfhound Press 1991), Introduction: ‘Ireland is know for its tenacious belief in God: our early poetry, in Gaelic or Latin, is rich and lyrical in its response to that God, but that is not my concern here. The theme of this anthology is the vacillation, indignation and occasional rapture that Irish poets have experienced in their response, as poets, to religious faith. [12]; Calls John Kells Ingram’s ‘Utinam Viderem’ the first Irish poem to urge a complete humanism … from a sonnet sequence stirred by the postivism of Auguste Comte [12]; In the Great Hunger Kavanagh’s poor hero, Maguire, has a hunger for life that is totally unfulfilled; the Church has made an evil thing, a valley of tears, mined with temptations, every signpost at every crossroads pointing towards Hell and damnation. [14]; Louis MacNeice, growing up in a zealot faith which served only to lead men towards despair, also found despair in any form of humanism. [...] MacNeice’s poetry charts his personal decline from faith into gnawing emptiness [14]; And yet Padraic Fallon succeeded in a poetry that is religious in the traditional sense and is also perhaps our finest achievement; it succeeds because the trappings of faith so beloved in Ireland, the statues, the beads, the rules, the dogmas, are ignores and the mystery [14] of religion is fully internalised. His poems are profoundly personal, not side-tracked by any shifts in social conditions, and yet the poems remain fully alert to the ultimate mystery that remains in any religious faith. He is a clear, unsentimental eye, his religious poetry remains rich and valuable in a perennially satisfying way.’ [15]

European Poetry Academy: ‘Not averse to a little verse’, The Irish Times [Weekend], 21 April 2001: Deane reports on first meeting of European Academy of Poetry in Mondorf, nr. Luxemburg; ‘I sat for a long times, awed by the company, awed and inspired by the high ideas expressed. To my left sat the great Inger Christensen of Denmark; to my right the legendary Andrei Voznessensky. When I offered a thought, in my hesitant French, I was smitten by the fac that they listened to me. Very soon it turned out that I was, perhaps, the one most inclined to getting facts, figures and details worked out. I was elected, for my pains, general secretary of the academy.’ (p.6.)[ top ]

Undertow (2002): ‘He stood perfectly still. The seal in the shallow water in front of him, went round behind him. He stood, tense with excitement. He could see its shape move with beautiful swiftness a small distance to his right. Then the head appeared again. They were motionless, watching one another. There was a trembling in his body that seemd to be joy, that took away all sens eo fchill. The seal did not move; it watched him ... He reached his hand under the water, bending towards that dark shape. The beast moved, with slow deliberation, towards his hand and he felt its head nudge gently against his palm ... He knew the great privilege he had been given, a grace offered for once and for ever ... he stood strong and momentarily at peace.’ (Quoted in Maurice Harmon, review of Undertow, in Books Ireland, Dec. 2002, p.311.)

‘Galway Kinnell: ‘A Generous and Fetching Poetry’, article on Galway Kinnell, in The Irish Times [“Essay”; Weekend] (9 April 2005), p.12: ‘[...] Kinnell has always been aware of the rapid demise of what is precious to human living. Poetry then, has become for him a way of admonishment. But this is done from the inside out, by a portrayal of the individual’s experience of gravity and of grace. From this personal window, looking out, he has written one of the most effective longer poems on the tragedy of the Twin Towers. I do not wish to suggest that he sets himself up as a kind of Jonah or Job to our times, but that his exploration through poetry is a deeply serious one, done with a deftness and lightness that leave the reader gasping with recognition.’ [Quotes from “When One has Lived a Long Time Alone”, continuing:] ‘Some years ago, the wise and discrete US ambassador to Ireland, Jean Kennedy Smith, gave a small party in the residence in the Phoenix Park at which she had asked Galway Kinnell to read his poems. The gentle yet resonating voice, the humanity and wholeness of the experiefice, the kindly and knowing awareness. of our earthy living, all of it offered a view of ambassadorship that was richly rewarding and deeply moving. The presentation of the possibility of hope and redemption through such a voice, in such a location, was one of the profoundest presentations I could ever imagine of what has been a once great nation. Kinnell’s return to Ireland, and to Cúirt is an occasion to be cherished and celebrated.’

Notes

Pat Boran - Boran, ed., Wingspan: A Dedalus Sampler (Dublin: Dedalus Press 2006), is dedicated to J. F. Deane.

David Gascoyne: James Fergusson (Bookseller), compiler of the library Catalogue of David & Judy Gascoyne, lists J. F. Deane, Winter in Meath: [poems]. (Dublin: Dedalus [1985]) as Item 448, being inscribed by the author on the title-page, ‘with love – John F. Deane’. £30. The book is available from Fergusson, 39 Melrose Gardens, London, W6 7RN (UK); email jamesfergusson@btinternet.com. [c.2010.)

[ top ]