Life

| b. 16 Oct. 1944, Stella Maris Nursing Home, Earlsfort Tce., Dublin; son of [Justice] John Durcan, barrister and later judge on Western Circuit, with whom always a problematic relationship - his father being authoritarian and occasionally violent; related through his mother Sheila’s family to the MacBrides and Gonnes - notably his grand-aunt Maud Gonne, whom he visited with his mother and siblings at Roebuck house in 1949 [‘The MacBride Dynasty’]; raised at 57 Dartmouth Sq., Dublin, and Turlough, Co. Mayo, where an aunt ran a pub; suffered bone disease [myelitis] in teenage and was hospitalised for some months; initially studied Law and Economics at UCD to please his father; encountered John Jordan [‘truth of the heart’s affections’]; gradually abandoned studies and was corralled by relatives in Donahoe’s Pub, Merrion Lane, and committed to St. John of God’s, the first of several forced sojourns in mental institutions, aetat. 19; afterwards sent to Harley St. and subjected to electro-shock and gas treatment; escaped from St. Patrick’s, Dublin, and lived uncertainly away from home in Dublin, socialising with Patrick Kavanagh, Brian Lynch, and others; moved to London in 1966 and started work at North Thames Gas Board [a self-confessed ‘misfit’], 1967, visiting Tate Gallery of Modern Art at lunchtimes, viewing in particular the paintings of Francis Bacon; |

| with Brian Lynch, issued Endsville (1967), under the New Writers’ Press imprint (fnd. Michael Smith); received positive review from Patrick Kavanagh; invited to accompany Kavanagh to his wedding at behest of his wife Kathleen, and there met his own wife-to-be Nessa O’Neill, 1968, with whom two dgs., Sarah and Síabhra, after a marriage at Brown’s St. George Hotel, London; recorded poems for Harvard University and British Council with Brian Lynch, 1969; with Martin Green, fnd. and ed. Two River (1969-71), a literary quarterly; returned to Ireland and settled in Cork, 1970; commenced a degree course in medieval history, and archaeology under M. J. O’Kelly at UCC; grad. 1973 (1st Class Hons.); contrib. to Magill, Choice, and Cyphers; his poetry was included in Padraic Fiacc, ed., The Wearing of the Black (1974); winner of Kavanagh Award, 1974 and issued O Westport in the Light of Asia Minor (1975); contrib. weekly column to Cork Examiner, 1977-[1984]; ed. of Cork Review, 1980; collapse of his marriage to Nessa, 1984 [‘the pure, orginal brokenness of our marriage’]; moved from Cork to Dublin; issued The Berlin Wall Café (1985); appt. Writer in Residence at Univ. of Ulster, Coleraine, 1984-86; had a son, Michael John O’Neill, with Jan[et] O’Neill, then a postgraduate student, b. 1988; visited Sao Paolo in Brazil on a British Council invitation; |

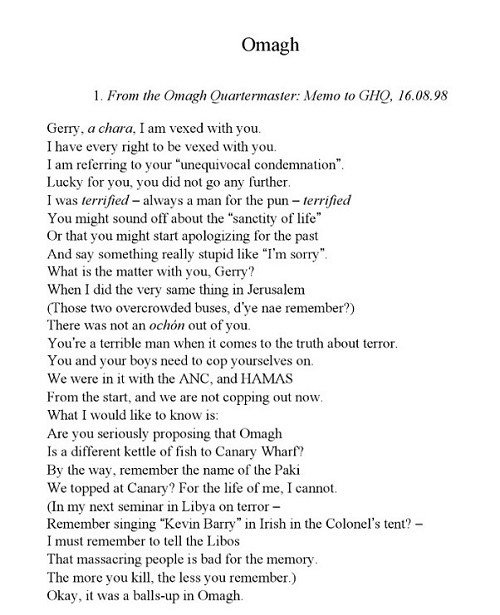

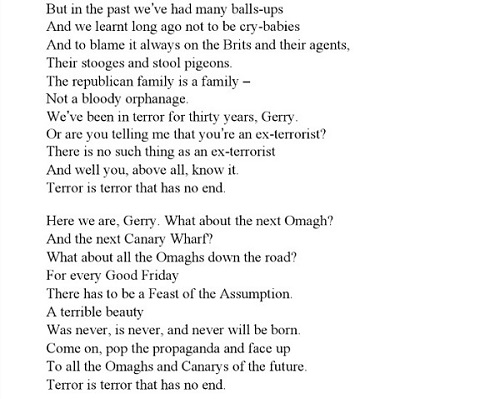

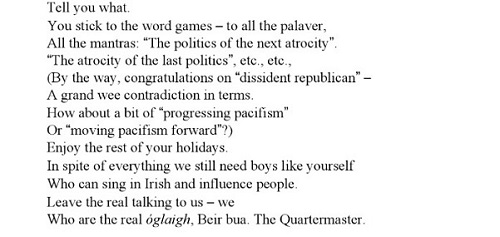

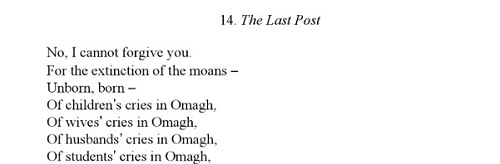

| received Cholmondeley Poetry Award (£2,000) of British Society of Author and the Whitbread Prize, 1990; TCD Writer in Residence, 1990; engaged in reading tours in America and Russia; co-authored “In the Days Before Rock ’n Roll” with Van Morrison, on Morrison’s album Enlightenment (1990); supported successful Presidential campaign of Mary Robinson; colloborated with artists and musicians such Mary Farl Powers and Micheál Ó Suilleabháin; commissioned to write verse-impressions of paintings in the collections of the National Gallery of Ireland [NGI], resulting in Crazy About Women (1991), and another for National Gallery, London, in 1993 (Give Me Your Hand, 1994); issued Daddy, Daddy (1990), winner of Whitbread Poetry Prize; quoted by President-elect Mary Robinson on Irish emigrants robbed of choice in her victory speech, RDS, 9 Nov. 1990; elected to Aosdána; read at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, summer 1995; responded to the IRA atrocity with a litany-poem of the victims’ names (“Omagh”); spoke again of Omagh on Writers in Profile RTÉ interview with Theo Dorgan (1999); issued Cries of an Irish Caveman (2001), an expression of despondency about recent developments int the so-called Celtic Tiger; received Cholmondley Award for Poetry, 2001; |

| issued Paul Durcan’s Diary (2003) and The Art of Life (2004) - shortlisted for Poetry Now Award, 2005; subject of interview-programme, dir. Alan Gilsenan, in “Arts Lives” series (RTE, 8 May 2007, 10.15pm); appt. 3rd holder of the Ireland Chair of Poetry, with an inaug. lecture on “Cronin’s Cantos: The Poet as Philosopher”, 3 March 2005. issued a new collection, The Laughter of Mothers (2007); received Hon. D.Litt from TCD, 11 Dec. 2009; issued Life Is a Dream: 40 Years Reading Poems 1967-2007 (2009); Hon. D.Litt from UCD, 2011; issued new collection, The Praise in Which I Live and Move and Have My Being (2012), his twenty-second collection - reworking Acts. 12:28 [New Testament] and celebrating the resilience of ordinary people in the face of the banking scandal and the fall of the Celtic Tiger; read at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, 2012; Durcan lives on Cambridge Rd., Ringsend [Irishtown], Dublin; received Lifetime Achievement Irish Book Award, 2014; The Day of Surprise (2015) a new collection [12 March 2015]; called by Fintan O’Toole ‘the national bard of the Republic of Elsewhere’ (cited in Tóibín, ed., The Kilfenora Teaboy, 1996, p.26). |

| “An Evening of Paul Durcan’s Poetry” was hosted by Poetry Ireland/Eigse Eireann at the Gate Th. as an 80th birthday celebration, 21th Oct. 2024; d. in a Dublin nursing home on Sat. 17 May 2025, after several years residence; funeral at St. Patrick’s Church, Ringsend (Dublin), Friday, 23 May; bur. in Aughavale Cemetery, Co. Mayo; numerous homages incl. those by President Michael D. Higgins, Poetry Ireland and very many writers and others in press and social medium; an Irish Times selection of ‘memorable lines’ was published on 19 May 2020 [online] |

|

DIB OCEL HAM OCIL FDA |

| Awards include— |

1974: Patrick Kavanagh Award |

|

[ top ]

Works| Poetry collections |

|

| Selected poems |

|

| [ top ] |

| Prose |

|

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| See also |

|

| [ top ] |

| Discography |

|

| Anthologies (inter al.) |

|

| Go to | |

| “Breaking News” - Paul Durcan commemorates the death of Seamus Heaney - RTE FM2 online, or see snippet on Heaney > Commentary > infra. | |

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Early collections: The Land of Punt (1988) includes ‘the Bonsai Man’. The Berlin Wall Café (1985) includes “The Pièta’s Over’ [‘make yourself at home in yourself not in a woman’]; “Raymond on the Rooftops”; “The Turkish Carpet”; “Girls Playing with Boys”. Going Home to Russia (1987) includes “Six Nuns Die in Convent Inferno”; “What Shall I Wear, Darling, to The Great Hunger?”. Daddy, Daddy (1990) includes “Loosetrife in Balyferriter” [ded. to Brian Friel at 60; ‘there is no god – only his Mother’]. Jesus, Break His Fall (Dublin: Raven Arts Press 1980 [rep. 1982]), 62pp. - with epigraph: ‘What goes up when the rain comes down? Answer me that now!’ - Danny Melt in Stone Mad by Seamus Murphy. CONTENTS: The Drimoleague Blues [11]; Sally [12]; Granny Tree in the Sky [13]; That Propellor I Left in Bilbao ..... [14]; At The Request of Nobody [15]; Save Eden Quay [16]; Mr Goldsmith, My Father’s Friend [18]; The Daughter Finds Her Father Dead [20]; Send a Message To Mary But Don’t Bother If You have An Important Programme to Watch On RTE Television 2 [22]; Mary Carey In Paris, June 1979 [24]; Hopping Round Knock Shrine In The Falling Rain: 1958 [25]; The Man Whose Name Was Tom-And-Ann [26]; Little Old Ladies Also Can Write Poems Such As This Poem Written in Widow’s Blood In A Rented Topstorey Room In Downtown Cork [27]; Tullynoe: Tete-a-Tete In The Parish Priest’s Parlour [29]; Charlie’s Mother [30]; On Buying A New Pair Of Chains For Her Husband [32]; The Collaring Of Manet By A Dublin Architect In The National Gallery [33]; At The Altar-Rails, Watching A Marriage Go Die [34]; Spitting the Pips Out - With The College Lecturer In Philosophy [36]; K.K.’s Lament for G.G. [38]; The Bearded Nun [39]; The Anatomy of Divorce by Joe Commonwealth [40]; My 27 Psychiatrists [41]; And Death Will Have A Great Deal, If Not Total, Dominion [41]; En Famille, 1979 [42]; Madman [42]; Fuckmuseum, Constance [43]; Maimie [43]; Marriage, Deafness, and the Problem of Erosion [44]; Naked Girl in Boardroom of Financiers, South Mall, Cork [44]; Honeymoon Postcard [45]; Death in the Quadrangle [46]; Danny Boy [47]; A Connaught Doctor Dreams of An African Woman [49]; This Week the Court Is Sleeping in Loughrea [50]; Bartle and Lulu: Orifice 14 [51]; Munch [52]; Veronica Shee From The Town Of Tralee [53]; On Seeing Two Bus Conductors Kissing Each Other In The Middle Of The Street [54]; The Boy Who Was Conceived in The Leithreas [55]; Uncle Frederick [57]; A Funk in Obelisk [58]; For My Lord Tennyson I Shall Lay Down My Life [60]; The Hole, Spring, 1980 [61]; The Death By Heroin Of Sid Vicious [62].

Cover Photos: Margaret Ruddle. Title page verso acknowledges editors of Cyphers; Celebration (Veritas); The Gorey Detail; Irish Times; Magill; Poems Plain; Structure; The Writers (O’Brien Press.) Raven Arts (Finglas) with business address at 34 N. Frederick St., Dublin. Recent books: Priorites by Bernard Smith; The Judas Cry by Conleth O’Connor; Half Time by Jule Wieland; The Habit of Flesh by Dermot Bolger; Perpetual Star by Brian Lynch; Stalingad: the Street dictionary by Michael O’Loughlins; Reductionist poem by Anthony Cronin; to be published shortly: Sensualities by Sydney Bernard Smith; Scurrilities by Sydney Bernard Smith; Journal by Arland Ussher. Published with assistance of An Chomhairle Ealaion (The Arts Council). Back cover matter: photo port; biog. notes; Arts Council Bursaries, 1976, and 1980-81.

Critics’ notices of first edn. of Jesus, Break His Fall: ‘Now once again we have one of-these poet-prophets in Paul Durcan, with a fierce innocence of vision and an equally fierce denunciation of godlessness which, in it’s essence, is greed and comfortable complacency, and, overall, an engaging hilarity that is light years beyond any preaching.’ (Francis Stuart), The Cork Review.) ‘This emphasis on individuality in our society frantic with it’s urge for anonymity is the glorious message of Durcanism. It is a vital message, expressed in a unique and vital poetry, and vibrant with an individual style.’ (John F. Deane, Irish Independent.) ‘Durcan’s concerns are the small everyday contingencies; his verses are inhabited by life’s unsung nonentities. He perfers [sic] the ordinary to the lofty; his adroit perceptions unmask the quiet moments in human behaviour and human desperation.’ (Gerard Smith, The Irish Times.) ‘He is like a scanner searching the Irish skies, and fixing on those points where all our contradictions are contained.... such a development in Irish poetry is enriching & liberating.’ (Sean Dunne, Sunday Tribune.)

Christmas Day (London: The Harvill Press [1996), 85 [3]; t.p. Christmas Day, with A Goose in the Frost; [“Christmas Day!, pp.1-78, in XIV sects.; “A Goose in the Frost” pp.79-[86], 1p. Notes, p.88]; incls. epigraph: ‘For kindness it is that ever calls forth kindness’.

Greetings to Our Friends in Brazil: One Hundred Poems (London: Harvill 1999), 272pp.; 257pp. CONTENTS: “Greetings to our friends in Brazil”; “Recife Children’s Project, 10 June 1995”; “The last shuttle to Rio”; “Fernando’s wheelbarrows, Copacabana”; “Samambaia”; “The geography of Elizabeth Bishop”; “Casa Mariana Trauma”; “The who’s who of American poetry”; “Televised poetry encounter, Casa Fernando Pessoa, Lisboa”; “Elvira Tulip, Annaghmakerrig”; “The daring middle-aged man on the flying trapeze”; “Brazilian Presbyterian”; “Jack Lynch”; “A visitor from Rio de Janeiro”; “Brazilian footballer”; “Please do not pedestalize”; “North inner city Brazilian monkey”; “The Chicago Waterstone’s”; “Remote control”; “O God! O Dublin!”; “Dirty day Derry”; “Norway”; “Eriugena”; “O’Donnell Abu!”; “Death of a Dorkel”; “The Binman cometh”; “Island Musician going home”; “The Bellewstown waltz”; “Thistles”; “October break (lovers)”; “Flying over the Kamloops”; “Man circling his woman’s sundial”; “High in the cooley”; “The only Isaiah Berlin of the western world”; “Karamazov in Ringsend”; “Notes towards a necessary suicide”; “Mecca”; “Holy smoke”; “Irish subversive”; “Paddy driver”; “Tinkerly Luxemburgo”; “Tangier in winter”; “Cissy Young’s”; “Notes towards a supreme reality”; “Tea-drinking with the gods”; “Buswells Hotel, Molesworth Street”; “Self portrait ’95”; “Ashplant, New Year’s Eve, 1996”; “We believe in hurling”; “Surely my God in Kavanagh”; “On first hearing news of Patrick Kavanagh”; “Waterloo Road”; “Patrick Kavanagh at Tarry Flynn, the Abbey Theatre, 1967”; “‘Snatch out of time the passionate transitory’“; “The who’s who of Irish poetry”; “Kavanagh’s ass”; “Francis Bacon’ double portrait of Patrick Kavanagh”; “The king of cats”; “The stoning of Francis Stuart”; “Dancing with Brian Friel”; “The rule of Marie Foley”; “Physicianstown, Callan, Co. Kilkenny, 30 April 1993”; “Portrait of Winston Churchill as Seamus Heaney, 13 April 1999”; “The pasha of Byzantium”; “The night of the Princess”; “At the funeral mass in Tang and the burial afterwards in Shrule of Dr. Hugh M. Drummond”; “Mother in April”; “The Shankill Road Massacre, 23 October 1993”; “The Bloomsday murders, 16 June 1997”; “Rainy day doorway, Poynztpass, 6 March 1998”; “North and south”; “Politics”; “On being commissioned by a nine-year-old boy in Belfast to desigh a flag to wave on the steps of city hall on the twelfth of July 1998”; “8 a.m. news, Twelfth of July 1998”; “The voice of Eden”; “56 Ken Saro-Wiwa Park”; “Mohangi’s island”; “Letter to the Archbishop of Cashel and Emly”; “A nineties scapegoat tramping at sunrise”; “Omagh”; “On the morning of Christ’s nativity”; “Sunday mass, Belfast, 13 August 1995”; “Self-portrait as an Irish Jew”; “Travel anguish”; “Waiting for a toothbrush to fall out of the sky”; “Making love inside Áras An Uachtaráin”; “Real Inishowen girl”; “Handball”; “Enniscrone, 1955”; “Private luncheon, Maynooth Seminary, 8 July 1990”; “Edenderry”; “The first and last commandment of the commander-in-chief”; “Somalia, October 1992”; “Meeting the President (31 August 1995)”; “The douce woman who was your neighbour”; “Meeting the patriarch, meeting the ambassador”; “American ambassador going home”; “Cut to the butt”; “President Robinson pays homage to Francis Stuart, 21 October 1996”; “The functions of the president”; “The Mary Robinson years.”

[ top ]

|

|

| See also Peter Hühn on Paul Durcan, inA Companion to Contemporary British and Irish Poetry, 1960-2015, ed. Wolfgang Görtschacher & David Malcolm (Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture] (NJ: John Wiley & Sons 2021), xviii, 634pp. [chap.]. |

| Associação Brasileira de Estudos Irlandeses, USP [Univ. de São Paolo / USP) |

ABEI Journal 22.2 [Special Issue: Celebrating Paul Durcan on his 76th Birthday; guest eds., Alan Gilsenan, Munira H. Mutran, Mariana Bolfarine] (Sao Paolo 2020). CONTENTS: Gilsenan, Mutran, & Bolfarine, Preface [13]; Alan Gilsenan, ‘Introduction For the .Poet Durcan, in his Seventy-sixth Year” [15]. Paul Durcan’s Poetry from the Irish and the International Perspectives. Alan Gilsenan, ‘The Poet Durcan & I” [67]; Kathleen McCracken, ‘Paul Painting Paul: Self-Portraiture and Subjectivity in Durcan ’s Poetry” [75]; Kim Cheng, ‘The Dublin-Moscow Line: Russia and the Poetics of Home in Contemporary Irish Poetry” [83]; Munira Mutran. ‘Paul Durcan ’s Poetry - A Self-Portrait in Contemporary Ireland” [99]; Rui Carvalho Homem, ‘On Paul Durcan and the Visual Arts: Gender, Genre, Medium’ [109]; Stephanie Schwerter & Marina V. Tsvetkova, ‘“Nachalstvo”, “Blat” and “Blarney” Paul Durcan Between Ireland and Russia” [119] Paul Durcan’s Poems Around the World. Paul Durcan [trans. by] Jorge Fondebrider, ‘The Divorce Referendum, Ireland, 1986’ [20]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] María Graciela Eliggi, 'The Most Extraordinary Innovation” [22]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Eduardo Boheme Kumamoto, “The Old Guy in the Aisle Seat” [24]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Gisele Wolkoff, “The Last Shuttle to Rio” [26]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Heleno Godoy, “The Daring Middle-Aged Man on the Flying Trapeze”; [30]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] José Roberto O’Shea, “Casa Mariana Trauma” [34]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Luci Collin, “Man Walking the Stairs: After Chaim Soutine” [36]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Noélia Borges & Monique Pfau, “Samambaia” [47]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Sílvia Maria Guerra Anastácio, “The Geography of Elizabeth Bishop” [46]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Madeleine Descargues Grant, “In memory of those Murdered in the Dublin Massacre, May 1974”; [48]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Stephanie Schwerter, “The Poetry Reading Last Night in the Royal Hibernian Hotel”; [50]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Marina V. Tsvetkova, “Zina in Murmansk”; [54]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Maria Yolanda Fernández-Suárez, “What Shall I Wear, Darling, to The Great Hunger?”; [58]; Paul Durcan [trans. by] Moya Cannon, “Going Home to Mayo, Winter, 1949”; [60]. Poems For a Poet. Celia de Fréine, One Giant Step on Behalf of the Elderly” [135]; Damian Grant, “[Paul Durcan” [137]; Moya Cannon, “Hands” [139]. Recollections of Paul Durcan. Derek Mahon, “Orpheus Ascending The Berlin Wall Café by Paul Durcan” [143]; Katie Donovan, ‘“Being Sensible”: Paul Durcan’s Anarchic Vision’ [147]; Niall MacMonagle, “Fiercely to Myself" [149]; Paul Muldoon, “The Assembly of Paul Durcan” [155]. Voices from Brazil. Heleno Godoy, “Paul Durcan Dances Down to Brazil” [159]. |

| —Available online; accessed 30.12.2024. |

[ There is an 30-min. Writers in Profile interview by Theo Dorgan in 1999 on Loopline at Irish Film Institute - online; accessed 21.05.2025. ]

[ top ]

Commentary

[Q.auth,] interview with Paul Durcan, in Cork Examiner (18 June 1979), q.p., notes that the epigraph for A Snail in My Prime is taken from Francis Bacon, whom Durcan most admires, quoting: ‘I would like my pictures to look as if a human being had passed between them, like a snail, leaving a trail of the human presence and memory trace of past events as the snail leaves its slime.’ Referring to Bacon’s “Study of a Dog” (1952), Durcan adds: ‘I was not only a Dog, I was Van Gogh as well’. The title poem, set in the Boyne Valley and embodying the surrender to feminity, contains the lines: ‘At dawn, at the midwinter solstice, / We creep into the corbelled vault / Of the family tomb. Down in dark / Death is a revealing of light / When a snail inherits the sky, / Inherits his own wavy lines; / When a snail comes full circle / Into the completion of his partial self.’ Durcan identifies Francis Stuart as a key to his development, ‘unlocking a network of harmonic connections’.

| Seamus Heaney: Heaney begins a review of the Collected Poems of Patrick Kavanagh (2005) by quoting Durcan: ‘On the one hand, there is the first sentence of Patrick Kavanagh’s “Author’s Note” to the old 1964 Collected Poems: “I have never been much regarded by the English critics,” a sentence he could fairly repeat if he were still alive. On the other, there is Paul Durcan who speaks for the Irish crowd when he declares that he doesn’t “read” Patrick Kavanagh, he “believes” in him.’ He continues: ‘[...] his later “comic” poems where he endeavours “to play a true note on a slack string” look back to the “come all ye” ballads of his country background, while sounding all the while like an early warning of subversions to come from the school of New York and the beats of San Francisco - and also, of course, from his believer Durcan.’ (Guardian, 1 Jan. 2005 - available online; accessed 23.03.2012.) |

[ top ]

Derek Mahon, ‘Orpheus Ascending: The Poetry of Paul Durcan’, in Irish Review, 1 (1986), pp.15-19; rep. in Journalism, 1996, pp.115-18 [though without the pastiche]: notes that ‘Durcan is not a surrealist but a cubist, one transfixed with the simultaneity of disparate experience, all sides of the question, the newspaper headline, the lemon and the guitar - a man with eyes in the back of his head.’; ‘obscurely aware that he is temperamentally suited to the role of sacrificial victim’ (p.116); ‘One critic has remarke that this new collection “elevates self-pity to a condition of heroic intensity”. I would go further and say that the heroism transcends self-pity.’ (p.117); ‘But where durcan sees an empty tomb I see Orpheus ascending into the light, an exemplary sufferer, a hero of art, to resolve his despair in song, inspired by a lost Muse.’ (p.118); characterises the collection as ‘the renunciation of a sometimes too facile fluenchy for the taut strings of a perfected artistry. Emerging into the light, he has given us his best book yet.’ (p.118; End). Note that original includes a pastiche of a ‘Durcan poem’.

| Sean O’Brien, “On Not Being Paul Durcan” |

|

| —from Ghost Train (1995) - available at Pan Macmillan - online; accessed 04.03.2020. |

[ top ]

Seamus Heaney: ‘[…] Take a poet in Ireland like Paul Durcan, who seems to be connected up with the times: of course he is, but he’s refusing the terms. In Durcan’s case, what is dream refusal can be taken for social comment. (Richard Kearney, ‘Interview with Seamus Heaney: “Between North and South: Poetic Detours”’, in States of Mind: Dialogues with Contemporary Thinkers on the European Mind (Manchester UP 1995, p.107; for further, see under Heaney, “Quotations”, infra.)

Joe Jackson, interview with Paul Durcan, ‘Conferring with the Linesman’, in Hot Press (Christmas 1987): quotes Durcan: ‘dark world of repression in the fifties’; ‘we were educated to believe that women were, on the one hand, untouchable and pure and on the other hand, that they were the source of all evil’; ‘The whole point about art is to rescue the feelings of the individual from things like what the Nazi philosohy stood for, which was the obliteration of the individual. So, every time you touch an individual watith a poem, a song, even a magazine article, you are changing the world’. Also, ‘There is a genuine piety at work there as well as the humour. I do believe in that line by Kavanagh, “satire is unfruitful prayer / Only wild shoots of pity there.”’ (p.45.)

Harry Clifton, ‘In the work of Paul Durcan, we have a realisation of Patrick Kavanagh’s idea of Comedy, or the Comic Vision, as Abundance of Life. Kavanagh may have outlined the blueprint for such a vision but Durcan has filled in the spaces.’ (See Clifton, ‘Available Air: Irish Contemporary Poetry 1975-1985’, in Krino, 7, 1989, pp.21-22.)

Edna Longley, The Living Stream: Literature and Revisionism in Ireland (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe 1994): ‘It [is] therefore Durcan who resumes the full range of his predecessor’s [Patrick Kavanagh] social anger (which declined into a narrower, paroanoid focus on literary Dublin), and re-connects it with “queer and terrible things” in the unconscious.’ (p.214.) ‘Durcan’s visionary radicalism … criticises a particular status quo (p.182.) ‘Durcan’s furious fantasies assail verbal pieties which mask materialism, sexism, the commodification of relationahisp and of art, authoritiarianism, the Church, and the violent subject of Nationalism.’ (p.214.) ‘The hypocrisy, cruelty, indifference and evasion diagnosed by Durcan’s socially explicit poems[,] condition the schizophrenia in his strange dark visions.’ (pp.214-15.) ‘Durcan seems to base his authority, which has a metropolitian cast, on a dissident, post-’sixties mutation of his family’s involvement with the institutions of the state.’ (p.220.)

Edna Longley reviews Greeting to our Friends in Brazil (Harvill), in The Irish Times ( 20 March 1999): ‘If you want densely-textured lyric or honed epiphany or mille-feuilles allusiveness, you are in the wrong shop’; ‘aims at Whitmanesque saturation’; ‘bulging with characters and conversations’. The title [poem] ‘seeks to [disturb] and defamiliarise … some may think - in my view, wrongly - that the heterogeneity is now so far advanced that Durcan should button his lip.’ Remarks that the collection includes ‘a sequence on Kavanagh and another of Durcan’s subtle dialogues with Seamus Heaney’; notes that the poems ‘may … exclude people outside the obsessive Catholic / Nationalist romance’ and ‘buries Republican and Loyalist violence in the same unequivocal grave’. “Omagh” incorporates includes three litanies, with concluding statement: “I cannot forgive you”. Finally, ‘he is one of the few contemporary poets who make poetry matter.’

Fintan O’Toole, ‘In the Light of Things as They Are: Paul Durcan’s Ireland’, in The Kilfenora Teaboy: A Study of Paul Durcan, ed. Colm Tóibín (Dublin: New Island Books, 1996), ‘[The poems] allude to a world that is more real than invented. It is the world of the burgeoning middle class Ireland whose culture is displaced and whose history can only be measured by the succession of cars.’ (p.31.)

| See Eleanor Bell, ‘Reactions to Tradition Since the 1960s’ [chap.], in Modern Irish and Scottish Poetry, ed. Peter Mackay, Edna Longley & Fran Brearton (Cambridge UP 2011). |

|

| —Eleanor Bell, op. cit.(2011), pp.245 - available online. |

[ top ]

Gerald Dawe, ‘The Suburban Night [... &c.]’, in Elmer Andrews, ed., Contemporary Irish Poetry: A Collection of Critical Essays (London: Macmillan 1996): ‘[in Durcan’s poetry] [w]omen represent and embody freedom, rebelling against the feeble conspiracies of male fantasies by living in much closer harmony with their true selves.’ (p.183).

Arminta Wallace, ‘Its the body Speaking’ [interview article], in The Irish Times (18 Feb. 1999): ‘The problem, really, is where to begin […] how else to describe a conversation with Paul Durcan than as a roller-coaster ride […].’ Quotes Durcan: ‘I went to Brazil in 1975 under the auspices of the British Council for a month’s tour, a series of readings […] In one place I read there had never been a poetry reading, ever. People came out of curiosity, and it was a very strange experience for all concerned. On that occasion, particularly, I felt I was really from another planet. […] I met a lot of nuns and priest there, almost all Irish, and to me they were heroes and heroines of the kind of people sang and talked about in the 1960s. Although I got the feeling that the Pope has, for some reason I just can’t figure out, alienated the vast masses of people in South America - some of them outstanding theologians whom you’d think, even out of cold Realpolitik, the Church would wish to keep - the brightest and the best. One of the things that astonished me was that ther are so many Presbyterians there. An awful lot of people have left the Catholic Church […] ’ [&c.] See also Battersby, [review article,] in The Irish Times (5 May 1993), criticises Durcan for ‘performance’ and ‘ventriloquism’. [Query: possible confusion between Wallace and Battersby as author of the interview (18 Feb. 1999), supra.]

Declan McCormack, ‘A Brush with Death on Bondi Beach […] the bard of the broken hearted’, Sunday Independent (21 Oct. 2001): ‘Durcan’s poetry lends itself to parody’ [offers an example; and cf. D Mahon, in Irish Review, supra]. Durcan recounts that he lives alone in Ringsend since breaking up with Cita, ‘the fortysomething country-woman who “stole my heart” and on whose “affection I ruminate”; confesses himself a news and sport junkie and a consumer of frozen dinners; alone, and not liking it: ‘Humans need companionship. Apart from nuns or priests who chose that life’; also, ‘Poetry is about trying […] to find […] the […] right ...’ - here McCormack interjects ‘woman’ and Durcan assents: ‘Well, yes.’ Durcan compares the national revulsion against Sept. 11th with the Irish toleration of IRA spectaculars ‘with a certain glee’ and speaks of ‘our own cold theoreticians of terror’. Speaks of the genesis of the current collection in ‘troglodytic ululations’ [interviewer] composed after the break-up with Cita, most of which were ‘rubbish’ until he hit on the image of self as cow / bull / lost heifer which ‘unlocked the code’. Article reprints “On Giving a Poetry Recital to an Empty Hall [ded. to Theo Dorgan]” (p.17; with half page photo.)

Bernard O’Donoghue, review of Cries of an Irish Caveman: New Poems (Harvill) in The Irish Times (17 Nov. 2001), Weekend, p.9: ‘Paul Durcan’s basic style has something in common with the prose narratives of Samuel Beckett - a kind of blithe, colloquial garrulity. The humour is up front; with Beckett, the challenge then is to see what (if anything) lies behind it, in the way of philosophy or a message for the times. This problem in Durcan’s case has generally been more acute; occasionally his work attains sudden and powerful compassion (as in Jesus, break his fall), but often the reader has to go with the facetious verbal flow.’ Quotes: ‘O let there be an end to politically-correct, sectarian, / nouveau-riche, low-skies-infested Ireland!’’, and queries, ‘How is the irony working here, if it is?’ and remarks: ‘[…] the apparent pharisaism of this induces some anxiety.’ Cites sections and titles, “Give Him Bondi”, “Sonia and Donal and Tracey and Patrick”, “Early Christian Ireland Wedding Cry”, “Christmas Day”, “Aunt Gerry’s Favourite Married Nephew Seamus”, “The Bunacurry Scurry”, “The Black Cow of the Family”, “The Girl from Golden”, “The Days before Milking Parlours and Mobile Phones”. Cites an Irish proverb lurking under “Early Christian Ireland Wedding Cry”, viz., má phosann tú an bean an tsléibhe, pósann tú an sliabh” echoed in ‘to the marriage of place - the mountain / to the lake’ [cf. sense of place]. Concludes, ‘all of which is to say that this is an extreme version of the usual Durcan mix, infuriating and haunting by turns […. &c.].’

[Shirley Kelly,] ‘Being a poet is not a viable position’ [interview-article], in Books Ireland (Dec. 2003): gives account of Paul Durcan’s Diary on the “Pat Kenny Show” (RTÉ), now published in book-form, and quotes Durcan’s remarks: ‘I have been asked many times over the years, especially by people who genuinely do not like what I write: Why is it that you present prose as poetry? In my defence, I say that I have spent most of my life truing to write poetry, I have given it a lot of thought through the years, and I am preoccupied with metric structure, as I’m sure anyone who writes poetry is. Everything I’ve ever published in verse has had to obey rules of metre; if somebody doesn’t hear that, the I wonder did I get it right.’ Durcan suggests that modern poetry has simply lost its way: ‘The movement in modern poetry, as in modern art, was towards the breakdown of traditional forms, an exploration of the prose line as the basis of poetry. I asometimes ask myself in anything has chnages since the days of Ezra Pound, who was such a great innovator. / Pound believed that poetry was the most efficient form of communication. A lot of what has been written since then is literarlly not memorabel, not just because it doesn’t appear to have any rhyme or sturcture, but also because there’s no feeling. It’s as if the writer continues to turn on the switch even though the fuse has gone.’; speaks of poetry in Don Delillo and John Ford; ‘With Friel and O’Casey before him, what you’re getting is the essence of the common language. Those plays are coming from snatches of conversation heard on the top of a bus, or whatever, And that’s why people can connect with them.’ ‘Growing up in Ireland in the fifties was a bit like living behind an iron curtain, with the Catholic hierarchy taking the place of the Kremlin, just another group of old men controlling the country. There was a fierce atmosphere of control, orthodoxy, conformity at all costs. It was in this context that I came to love radio and film; they were windows on to another world. It was a priest, a very intelligent priest, who told me that Elvis was “incarnate evil”, but it was a priest as well who introduce me to the great American writer Alastair Cook, by reading his reports in the Manchester Guardian during English class. Then I listened to Cook’s Letter from America on Radio 4, which has been running for about sixty years now and is still broadcast weekly, even though Cook must be well into his nineties now. / To me, Cook is the is the maestro of the essay. It’s a form that I’ve admired for a long time but I never had the opportunity ot try it until I met Marian Richardson, series producer at RTÉ, and we got to talking about it. We came up with the idea of a ten-minute essay on Pat Kenny’s show; he was enthusiastic, and that’s how it happened.’ (p.297.)

Catriona Clutterbuck, review of The Art of Life, in The Irish Times (30th Oct. 2004), Weekend: ‘In a score of books since the late 1960s, Paul Durcan has been concerned with the damage done to Ireland and the Western world by a prevailing scepticism and fear of free human nature. Ironically, Durcan’s impassioned poetry has displayed a related doubt about the potential for good in the natures of those he holds to account for such negativity. Durcan has become an essential voice because his work has steadily nudged both scepticisms - the one he attacks and the one he embodies - closer towards an attitude of faith. [...] The comic spirit that has sustained Durcan from the beginning, turned dark in his elegiac 2001 collection, Cries of an Irish Caveman. That book focused on the stripped and drowning ego of the isolated male tasting “the Eucharist of the nothingness of life”. In this latest collection, the swarming “everythingness” of life flows back to occupy that scoured space. Now, “Although I am globally sad I am locally glad / To be about to drive down that corkscrew road.” (“The Far Side of the Island”. Now, he knows himself “not afraid in the night / To be a back-seat passenger in a white Honda Civic / Or to be alone in water at my life’s conclusion”, because “In this same bathtub many have soaked / And all were chosen.” (“Santa Maddalena”.) […] In the opening poem of The Art of Life, Durcan declares himself to be a middle-aged male who is 19 years pregnant with the “Golden Island” of the Ireland he wants to bring into being. He must have conceived, therefore, in the mid-1980s - a period many consider a nadir of patriarchal social regression in recent history, here and elsewhere. Out of such dark is born the present volume, which revisits and injects light into some of his most famous and bitterly-tinged satires from that time. [...] Throughout this book, new life is evident the more Durcan focuses on old life, be it of the body or the body politic. The strongest resistance to despair comes from unlikely sources inside the system, bearers of the clichés of tradition and backwardness: the aged, the religious, the family male, the military. To these are given the songs of a people solidly in place, who acknowledge the cold but who cannot understand those who refuse the available warmth. In availing of that warmth, these poems generate it. In the voice of “A Robin in Autumn Chatting at Dawn” returning from his visit to the precipice: “With my hands behind my back and my best breast out, / My telescope folded up in my wings, my tricorn gleaming, / I emerge on the bridge of my fuchsia, / whistling: / All hands on deck! Hy Brasil, ho!”’

John Knowles, interview with Paul Durcan, in Fortnight [Belfast] (April/May 2005), pp.21-22: ‘The ability to absorb himself in places and events, is also something that marks his work. He says he’s relished the chance to spend more than a few days in Belfast and has hugely enjoyed just walking around the streets. His residence in Queen’s has coincided though with numerous public statements from Sinn Féin and the IRA following the Robert McCartney murder. Here something of the black anger that can characterise his poetry becomes apparent. He’s been reading all the newspapers and finds the various statements ‘depressing beyond words. Every day Sinn Féin and the IRA have come out with a new batch of lies. I say lies advisedly’, he says. ‘Obviously they’ve murdered a lot of people over the years, but they’re in the business of murdering language. Almost every day there’s a new set of lies ... Words have become devalued. If there was a Nobel, Prize for propaganda’, he adds, ‘Sinn Féin would have long ago won that prize. They’re out on their own ... ahead of all the other political parties’, but recent pronouncements, he suggests, are beyond propaganda, are nothing more than barefaced lying.’ (See full text - as attached.)

Anthony J. Jordan, The Yeats Gonne MacBride Triangle (Westport 2000), includes an account of Durcan’s response to the allegations of marital abuse and sexual assault on Eileen Wilson in Maud Gonne’s evidence before the divorce court in Belgium: ‘In the autumn of 1991, the poet, Paul Durcan, who is directly related to both the Gonnes and the MacBrides, made an intervention, when he gave a lengthy interview to Mary Dalton for the Fall issue of the Irish Literary Supplement, published in the USA . Eileen Wilson who married Joseph MacBride had five children, one of whom is Paul Durcan’s mother. Paul spent much of his childhood at Mallow Cottage, near Westport , where Eileen Wilson lived with her daughter. after the death of her husband in 1938. Durcan described it as “a place that was Eden to me”. / It is clear from the interview and his poetry, that he dearly loved Eileen Wilson. Eileen was the daughter of Thomas Gonne, outside of marriage, and thus Maud’s half sister. Durcan says that it was Nancy Cardozo in her 1979 biography of Maud Gonne, who related the story that one night in [9] Paris John MacBride assaulted ‘my grandmother ... No evidence was produced in the book, although it was presented as a scholarly book’. He said that since then, the story had occurred in several books ‘ - again never with any evidence’. He then expressed his shock to read in Professor Norman Jeffares’ life of Yeats, the story of the sexual assault of ‘my grandmother, without any substantiation whatsoever’. Durcan adverts to I lie possibility that the, ‘story may be true but no evidence has been offered by anybody’. He then states, ‘it may well be - this is speculation on my part .. that the source of all the pain I’ve been talking about in the last while, inay be in the letters from Maud Gonne to Yeats’. Durcan said that ‘the people in the Yeats-Maud Gonne Industry, would not have published this story about my grandmother, Eileen, until she was dead’. He also added’ 1 think that the person who has been unquestionably defamed, from the day almost of his execution in 1916, is John MacBride himself’. (End; pp.9-10; see further under Seán MacBride, as infra.)

Eve Patten, ‘Critical Perspective on Paul Durcan’, in Contemporary Writers (British Council 2008): One of modern Ireland’s most distinctive poets, Paul Durcan is renowned as both an outspoken critic of his native country, and as a chronicler of its emergence from the repressions of the 1950s to the contradictions of the present day. His work is aggressively satirical, dedicated to exposing a range of Irish ills: the hypocrisies of the church, the obfuscating bureaucracy of state and the smug bourgeois affectations of Dublin’s “chattering classes”. But he has a capacity too for lyricism and intense personal romanticism, as a poet of love, eroticism, and loss. His striking metaphors and dislocating images, meanwhile, result in a poetry which is extraordinarily visual and frequently, surreal. Celebrated for his dramatic and incantatory reading style he is, above all, a risk taker, unorthodox in his use of prayer forms, ballads, and free-flowing dramatic monologues, and relentlessly iconoclastic in his treatment of contemporary life and events. [See full text in RICORSO Library, “Criticism / Reviews” - as attached,, or go directly online.]

Christina Hunt Mahony on “Going Home to Mayo by Winter 1949” by Paul Durcan, in Irish University Review: A Journal of Irish Studies [Special Irish Poetry Issue, guest ed. Peter Denman] (Sept. 2009): ‘“Going Home to Mayo, Winter, 1949” does not bear one of Durcan’s zany trademark titles. It contains no delicious departures from reality like birds emerging from eyebrows (“Dun Chaoin”). It is not relieved by the comedy of naked security guards dancing through Bewleys. Although Durcan has disdained the term “surreal” as applied to these departures from realism because it does not define his intentions or process, the point at which the real and the highly imagined collide is a successful and idiosyncratic feature of many of his poems. [...] / “Going Home to Mayo” shares none of this tendency, except in the way it visualizes a class of a children’s book illustration and text - the anthropomorphized moon peering into the car, the warm glow issuing from the house upon arrival in Mayo, the childish recitation of names playing connect-the-dots across the country - Kilcock, Kinnegad, Strokestown, Elphin Tarmonbarry, Tulsk, Ballaghaderreen, Ballavary. [...] Journeying is an intrinsic part of this poem and of Durcan’s life and art - a peripatesis, conveying the negative features of rootlessness and loss and glossed with the uplifting air of a hopeful quest. After many such journeys home to the country the next destination for the poet was London, as it was for so many others, but then he went everywhere. No matter how many journeys, or the exoticism of the places he has visited and written about since - Russia and the old Soviet satellites, Brazil, Germany, and Western Canada - Durcan, our best and most authentic poetic witness of Dublin life and its changing parameters, still returns to Mayo, both in his poetry and in his life. / Rejection of the father or fathers, or the nation as defined by the father, is a recurring literary motif and one which never seems to become shopworn or to lose its relevance. In the latter case it seems that as long as there are nations this disassociation or rebellion will continue to compel. In Ireland the business of throwing out colonialist rubrics is replaced within a generation or two by the necessity to reject the paternalism of the newly-emergent nation. In Durcan’s case the rectitude of his father and the father’s world is a rich source of angst, treated with whimsical anomie, anger, humour, and often resulting in a crushing state of depression and a need for valid redefinition.’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or as attached.)

[ top ]

Poetry

O Westport in the Light of Asia Minor (1975) contains the title poem, as well as ‘Ness[a]’ and ‘Hymn to Nessa’, et al. The title poem first appeared in The Dublin Magazine (Autumn 1971), pp.81-82, ending: ‘The Judge said - They must be spared this man’s irrational fear. / O’Black Day and Fire outside my window / I will go out tonight and the first mansion in the / Town of Westport that I come to / I will take it downbrick by brick until they take me / away saying: Tell that to the Taoiseach. / So help me Anthony. And then maybe I’ll help you / with stories of Rough Love in Jericho.’

|

“On a June Afternoon in Saint Stephen’s Green” [‘And I thought, had I the choice I had been a woman / Instead I am strung up on a cloud called mind. / Even were I to walk naked my body were a cumbersome coat. / O fortunate soul, walking on her hips through the Green’]; “Phoenix Park Vespers”; “A Day in the Life of Immanuel Kent” [?sic] [‘Home then to Wifey, the Box and the Six-Pack, / The two brats and the possibility of copulation’]; “Wife Who smashed Television gets Jail” [‘the television itself could be said to be the basic unit of the family’]; “Goodbye Tipperary”; [Irish tolerance ‘of everything except women and freedom of conscience’]. (In Teresa’s Bar (Dublin: Gallery Press 1976) - includes “The Difficulty that is Marriage”; “She Mends an Ancient Wireless”, and “The Daughers Singing to Their Father”.)

Jesus, Break His Fall (1980) includes “Hopping Round Knock Shrine in the Falling Rain, 1958” [‘to get the ear of his Mother was a more practical step’].

“Ireland 1977”: ‘I have not “met” God, I have not “read” / David Gascoyne, James Joyce, or Patrick Kavanagh: / I believe in them. Of the song of him with the world for his care / I am content to know the air.’ (Q.source; quoted in Edna Longley, ‘Poetic Forms and Social Malformations’, in The Living Stream: Literature and Revisionism in Ireland, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe 1994, p.21.)

[ top ]

| Paul Durcan, “We resided in a Loreto convent in the centre of Dublin city” (1986; pub. 1987) |

|

|

[ top ]

Ireland 1990: ‘Yet I have no choice but to leave, to leave, / And yet there is nowhere I more yearn to live / Than in my own wild countryside / Backside to the wind.’ (Quoted by Mary Robinson, president of Ireland, in her victory speech ( Nov. 1990; see Fergus Finlay, Fergus Finlay, Mary Robinson: A President with a Purpose, Dublin: O’Brien Press 1990, p.9.)

So lonely: “I’ve become so lonely, I could die” - he writes, / The native who is an exile in his native land: / “do you hear me whispering to you across the Golden Vale? / Do you hear me bawling to you across the hearthrug?”’ (cited in Longley, op. cit, 1994, p.220.)

“My Bride of Aherlow”: ‘Or was it that in my black book sack / I carried too many years? / And that the hairs of my head were grey / And gelled in too many tears? […] O marry me how in my grave, in my grave, / My bride of Aherlow! [… &c.; 4 stanzas.] (The Irish Times [Weekend], 16 June 2001).

“The Pièta’s Over” includes the line: ‘It is time for you to get down off my knees / And learn to walk on your own two feet.’

“No. 13 East 1928 McKenna’s Barber Shop [ded. to Síabhra MacBride Walsh]”, in The Irish Times, 25 Nov. 2000): ‘I stop out of the pelting rain; / The barber murmurs “a damp day.” / I cite the east wind. He inclines fractionally - / “With the east wind, sir, the rain is usually dry. […]”’.

[ top ]

| Two poems ... |

|

|

| See also | |

| “They Say the Butterfly Is the Hardest Stroke” |

|

| —from The Days of Surprise; quoted on Facebook by Peter Quinn (31.05.2015.) |

| “The Laughing Receptionist in the GP’s Surgery” |

|

| Quoted by Eunice Yeates on Facebook (19.04.2017). |

[ top ]

|

||||||||||

[ top ]

Remarks

Two Rivers (First Editorial) [with Martin Green] - The editorial of the first issue of Two Rivers (1969) states the editors’ wish to ‘contribute to a climate more sympathetic to the writer [than that supplied by] giant groups [of publishers - thus avoiding] the deliberations of a group of some tycoon’s natchet=men as to whether or not the tycoon could increase his wealth out of the writer’s work’. Further: ‘[I]t is more important than ever to foster what little hope we have for a culture and language that have produced not only Shakespeare and Blake, or Yeats and Joyce, but those who we are lucky enough to still have with us; Auden, Ezra Pound, George Barker and MacDiarmid (the latter two being represented in this issue). Let us ackowledge the legislators.’ ((Two Rivers, I, 1 Winter 1969, p.5; quoted in Eleanor Bell, ‘Reactions to tradition since the 1960s’ [chap.], in Modern Irish and Scottish Poetry Reactions to tradition since the 1960s, ed. Peter Mackay, Edna Longley & Fran Brearton, Cambridge UP 2011, pp.245-46. Note: Bell comments: ‘central to this oppositional, DIY aesthetic was also an inherent reverence for literary tradition.’ - available online.)

|

Pure women: ‘We were educated to believe that women were, on the one hand, untouchable and pure, and on the other, that they were the source of all evil.’ (‘Conferring with the Linesman’, interview, Hot Press [Christmas issue] Dec. 1987.)

Free women: ‘In contrast [to men] women represent and embody freedom, rebelling against the feeble conspiracies of male fantasies by living in much closer harmony with their true selves.’ (Quoted by Gerald Dawe, ‘The Suburban Night’, in Contemporary Irish Poetry, 1992, ed. Elmer Andrews, p.183 [Chap. 9]).

Crazy About Women (1991), Preface: ‘Since 1980 I have regarded painting and cinema - the experience of looking at pictures wherever I happen to find them […] as essential to by practice as a writer.’ ‘Art begins in “formal improvisation” and the biggest influence in matters of form on my own improvised life, has been the cinema and - within the terms of the cinema - photography, painting, music and not the written word.’

[ top ]

References

Peter Fallon & Seán Golden, eds., Soft Day, A Miscellany Of Contemporary Irish Writing (Notre Dame / Wolfhound 1980), selects “The Difficulty that is Marriage”; “The Weeping Headstones of the Isaac Becketts”; “The Kilfenora Teaboy”.

Andrew Carpenter & Peter Fallon, eds., The Writers: A Sense of Place (Dublin: O’Brien Press 1980), selects “The Drimoleague Blues”, with photo-port., p.32.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3: selects from O Westport in the Light of Asia Minor, ‘Dún Choain; from Teresa’s Bar, ‘The Baker’; from Jesus, Break His Fall, ‘The Death by Heroin of Sid Vicious’; from The Berlin Wall Café, ‘The Marriage Contract’, ‘Bewley’s Oriental Cafe, Westmoreland St.’; BIOG, 1435 [dates as supra].

Patrick Crotty, ed., Modern Irish Poetry: An Anthology (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1995), selects “The Hat Factory” [286]; “Tullynoe: Tête-à-Tête in the Parish Priest’s Parlour” [289]; “The Haulier’s Wife Meets Jesus on the Road Near Moone” [290]; “Around the Corner from Francis Bacon” [295]; “from Six Nuns Die in Convent Inferno”, 1 [297]; “The Late Mr Charles Lynch Digresses” [301]; “The Levite and His Concubine at Gibeah” [301].

Bangor Heritage Centre (brochure): ‘Aspects Celebration of Irish Writing’ [festival title] (28th Sept.-2 Oct. 1994): ‘His first collection published in 1967 but it wasn’t until 1985 with The Berlin Wall Café that he came to prominence; since then […] one of the best-known and most popular writers in Ireland; his readings inevitably sell out almost immediately [&c.].’

[ top ]

Notes

Kith & Kin: Paul Durcan is related to Seán MacBride [q.v.], whose uncle Joseph MacBride (b. of John MacBride, d.1916) married Eileen Wilson [illeg. dg. of Thomas Gonne and half-sister of Maud Gonne], and was Durcan’s maternal grandmother, living with her dg. at Mallow Cottage, Westport after the death of her husband. Durcan’s son Michael (b.1987) lives in Portstewart, Co. Derry, with his mother, Jan O’Neill.

Oh, Willie! The allegedly sexual abuse of Eileen Wilson by John McBride caused Durcan ‘distress’ in view of the happy regard in which Eileen held MacBride. Durcan made a direct intervention in an interview for the Irish Literary Supplement (Fall 1991). See also Anthony J. Jordan, Willie Yeats and the Gonne-MacBrides, Westport Books 1997 and further under MacBride - as infra.

Bootboy Bishop?: Durcan’s satirical poem on Archbishop Diarmuid Martin was the occasion of several rebukes in the newspapers from Irish Times columnist Breda O’Brien and others in August 2008 - turning mainly on his account of the Dublin diocesan archbishop Diarmuid Martin as a Northside ‘bootboy’ doing the dirty-work for his Party Secretary, the Pope. Archbishop Martin has been involved in the controversial appointment of parish priests. See O’Brien, ‘Flawed archbishop unscathed by poet’s lazy attack’, in The Irish Times (23 Aug. 2008). He previously affronted clerical authority with “Cardinal Dies of Heart Attack in Dublin Brothel” and other poems.

Van Morrison: Durcan co-wrote and jointly sang the lyrics for “In the Days Before Rock and Roll” with Van Morrison, whom he eulogised in a Magill article of May 1988 [as supra].

[ top ]