|

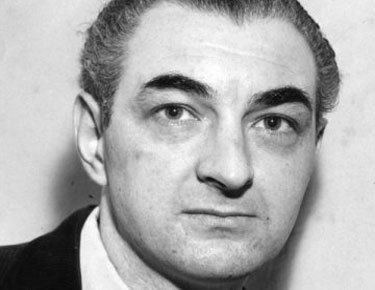

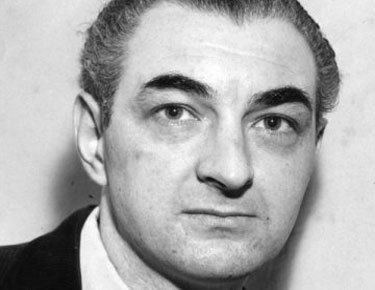

Patrick Galvin

Life

| 1927-2011; b. [poss.] 15 Aug. 1927, 13 Margaret St. [off Barrack St., nr. St Fin Barre’s] , Cork; with seven siblings. his childhood was blighted by the poverty and his parents’ troubled relationship; ed. Presentation Brothers (CBS); encouraged to read by a Jewish neighbour called Goldman who taught him copper-plate writing and gave him his first job as a messenger-boy; worked as newspaper boy and distributed pamphlets in pubs; his disruptive behaviour [‘beyond parental control’] resulted in 3 years sentence to St. Conleth’s Industrial School (Daingean, Co. Offaly) [reformatory], 1938-41 [3 yrs. by his own account]; influenced by an English teacher and a veteran of the Spanish Civil War [prob. the model for William Franklin in Raggy Boy]; returned to Cork, discarding the suit supplied behind a hedge, 1939; and projectionist in Washington St. and Lee cinemas; travelled to Belfast to join American Army but enlisted in RAF Bomber Command mistake instead, 1942; served in UK, Palestine, and Sierre Leone (Coastal Command, Africa); variously employed in London in post-war period; encounter Seamus Ennis, who encouraged his folk-singing; |

| |

| made 7 records of of Irish folk-song from 1798-1923 for WMA, Stinstson Records and Riverside Records, NY; wrote songs incl. his “James Connolly”, sung by Christy Moore; broadcast poetry with BBC; issued Heart of Grace (1957); made Life and Poetry of J. M. Synge (BBC3, 1959), a radio feature; briefly moved to Dublin, 1962; a play, And Him Stretched (Unity Theatre, London 1962); returned to London, 1963; wrote Boy in the Smoke (BBC 2, 1965); settled at Roaring Water Bay, W. Cork, 1965; Cry the Believers (1965), play; travelled in Spain, Israel, Germany, 1967-69; The Wood Burners (1973), poetry; resident dramatist at Lyric Theatre, Belfast, as poet-in-residence,1974-77, and recipient of the Leverhulme Fellowship in Drama, 1974-76; Nightfall to Belfast (Lyric Th. 1973) - a play involving testimonies to state brutality in monologue form which was nearly interrupted by a 300 lb. car-bomb, fortunately defused outside the Lyric; dir. Yeats’s Purgatory (Lyric Th. 1974); The Last Burning (Lyric 1974), based on the story of Brigid Cleary; We Do [var. Did] It for Love (Lyric Th. 1975), ballad opera set in N. Ireland Troubles, and centred on a merry-go-round; also The Devil’s Own People (Dublin Th. Fest. 1976); issued Man on the Porch: Selected Poems (1979); spent six months in Spain; resident writer, East Midland Arts, 1980-82; |

| |

| wrote Class of ‘39 (BBC4 1981), radio play; read at Washington Library of Congress; wrote My Silver Bird, with music by Peadar O’Riada (Lyric Th. 1981); wrote and dir., I Mind My Time (Belfast Fest. 1982), one-man show; dir. Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape (Belfast Th. Fest. 1982); travelled in Spain for research; moved to Ballycotton, East Cork and appt. writer-in-residence, UCC (NUI); issued City Child Come Trailing Home and Landscape and Seascape (RTÉ 1983), radio plays; elected to Aosdána, 1984; wrote Quartet for Nightown, and Wolfe (RTÉ 1984), radio plays; settled in Belfast; adapted The Country Woman by Paul Smith (BBC4 1986); adapted The Monkey’s Paw by W. Jacobs (BBC4 1986); dir. Oscar Wilde (Brighton Pavilion 1987); issued Folk Tales for the General (1990); Song for a Poor Boy (1990); undertook a reading tour in Mexico and Newfoundland, 1991; returned to Cork, 1991; Song for a Raggy Boy (1991), autobiography, set in an Irish reformatory on the eve of World War II featuring clerical brutality and abuse of the 13-year old boys Patrick Delaney and Liam Mercier; adapted and directed by Aisling Walsh with Chris Newman and John Travers as the two boys and Aidan Quinn as William Franklin, a lay teacher who tries to protect the boys from abuse; The Death of Arthur O’Leary (1994); O’Shaugnessy Award for Poetry from Irish American Cult. Institute, and reading tour in USA, 1994; cofounded Munster Literary Centre with his wife Mary Johnson; |

| |

| writer in residence and ed. Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown Co. Anthology (1996), incl. his own Village Diary; hix New and Selected Poems was edited by Greg Delanty and Robert Welch (1996); The Raggy Boy Trilogy issued 2003, to be filmed by Aisling Walsh; suffered a stroke, 2003; awarded Hon. D.Litt at UCC (NUI), 2 June 2006; MSS copies of his plays are held in the John Burns Library of Boston College; d. May 10 2011, aetat. 83; Galvin was married four times; he is survived by his children, Christine Bygraves, Macdara Galvin, Grainne Galvin [with Johnson] and the entertainment writer Patrick Newley [pre-dec.]; his wife Mary pre-deceased him by some months; a Sunday Independent obituary appeared on 15 May 2011. DIL DIW OCIL |

|

|

Alcetron Encyclopedia - online (10.01.2020)

|

[ top ]

Works

| Poetry |

- Irish Songs of Resistance (Workers’ Music Association 1955).

- Heart of Grace (London: Linden Press 1957); Christ in London (London: Linden Press 1960).

- The Woodburners (Dublin: New Writers’s Press 1973); Midnight and Other Poems (1979).

- Man on the Porch (London: Martin Brian and O’Keeffe 1980) [var. 1979]; Folk Tales for the General (Dublin: Raven Arts 1990).

- The Madwoman of Cork (1987) [portfolio edn., infra].

- The Death of Arthur O’Leary (Cork: Three Spires Press 1994), 26pp.

|

| Collected Poems |

- Greg Delanty & Robert Welch, eds. & intro., New and Selected Poems of Patrick Galvin (Cork UP 1996), 128[133]pp.

|

| Plays |

- And Him Stretched (Unity Th. London 1961).

- Cry The Believers (Eblana Th., Dublin 1962 [var. 1960).

- Boy in the Smoke (BBC Wednesday Play 1965).

- The Last Burning (Lyric Th. Belfast 1974).

- We Do It for Love (Lyric Th. Belfast 1975).

- Nightfall to Belfast (Lyric Th. Belfast 1973 [var. 1976]).

- The Devil’s Own People (1976).

- The Class of ’39 (BBC Radio 4 1980).

- My Silver Bird (Lyric Th. Belfast 1981).

- City Child, Come Trailing Home (RTÉ radio 1983).

- Landscape and Seascape (RTÉ radio 1983).

- Quartet for Nightown (RTÉ radio 1984).

- Wolfe (RTÉ radio 1984)

- The Cage (Cork Arts Th. 2006).

|

| Autobiography |

- Song for a Poor Boy: A Cork Childhood (Dublin: Raven Arts Press 1990), 111pp. [1-85186-080-0].

- Song for a Raggy Boy (Dublin: Raven Arts 1991).

- Song for a Fly Boy (initially due 1997; still pending in 1998 - see Irish Times online; ultimately comprised in the collected edition as The Raggy Boy Trilogy, 2003).

|

| Collected |

- The Raggy Boy Trilogy (Raven Arts 2003) [contains all three listed above].

|

| Miscellaneous |

- Letter to A British Soldier on Irish Soil (Detroit: Red Hanrahan Press 1972) [ltd. 500].

|

| Translation |

- Yilmaz Odabaci, Everything But You, trans. Patrick Galvin & Robert O’Donoghue [Munster Lit. Centre] (Cork: Southword 2006), 66pp.

|

| Discography |

- The Madwoman of Cork, as cassette recording; Songs for a Poor Boy (1989).

|

Bibliographical details

Portfolio: his longer poem “The Madwoman of Cork” was been produced in a portfolio edition of 1987 with 8 lithographic illustrations by Kent Clark, one for each stanza; copied of the ltd. edition of 75 are held in Harvard University Library, Boston, Massachusetts, USA The Arts Council of Northern Ireland, Belfast, Northern Ireland St. Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada The University of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada The Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Canada The Art Gallery of Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada The Tyrone Guthrie Centre, County Monaghan, Ireland The Ulster Museum, Belfast, Northern Ireland and numerous private collections worldwide. Kent Jones holds the Chair of Fine Art at Memorial University of Newfoundland.

[ top ]

Commentary

Michael Smith, review of New and Selected Poems (1997), in The Irish Times (11 Jan. 1997), quoting extensively, remarking that the poetry is not politically correct (without praised or blame), and further that ‘the poets affinities are with the odd, the deprived, the dispossessed and the marginalised’, characterising him as a ‘performance poet’.

Robert Welch & Greg Delanty, New and Selected Poems of Patrick Galvin (Cork UP 1996), Introduction [by Welch], pp.vii-xvi. ‘[P]articular importance may be attached to the self-respect and fraternal pride that was fostered in the nineteenth-century craftsman’s an artisans’ guild in Cork. The rights of the skilled craftsmen were jealously protected in this context of economic prosperity, which meant that there was a hierarchy of labour and that a sense of value was attached to physical work. Cork had (still has?) a working class not easily cowed and one keenly concerned with issued of social justice. This is one reason why Jews were welcome in Cork in the early twentieth century, when other cities adopted distinctly anti-Semitic attitudes. The small but very significant Jewish population of Cork surfaces in Galvin’s autobiographical writings in a hatred of fascist, totalitarian and authoritarian ideologies, which is everywhere evident in his poetry and drama./The most formative influence, however, on Galvin’s radical liberalism was the fact that he grew up in a city with a tradition of rebellion after the Anglo-Irish war of 1919-1922 won partial independence for Ireland from Britain. There was much disillusionment, and that mood informs the atmosphere of the post-revolutionary school of realist prose, chief among which was that of the Corkmen Frank O’Connor and Sean O’Faolain [...]. Certainly the spirit of Connolly’s humane socialism informed Galvin’s boyhood and earl manhood as much as the sacral transcendentalism of Patrick Pearse./However, the figure of Michael Collins, IRA leader and one of the chief negotiators of the Treaty haunted Galvin’s imagination, as it did that of many young men in Cork and the rest of Ireland in the post-revolutionary period.. His ruthlessness, integrity and daring and the fact that he was ambushed and killed in mysterious circumstances made him a figure of mystery and power, qualities celebrated in Galvin’s lament for the “Big Fella” and in “The White Monument” [xi] [...] But another element creeps in as well, ad a crucial and determining one in Galvin’ range of voices: it is a note of excited celebration that comes from Federico Garcia Lorca. Galvin learnt from Lorca how it was possible to unite folk energy with modernist and indeed surrealist effects. This alliance is bravely attempted in “The White Monument” when the Irish caoineadh and Lorca’s lyric enthusiasm are joined to evoke and salute the chthonic power and vital masculinity of Michael Collins ... bull-fighting imagery is prominent in [the poem]. ... modern English cannot sustain a long note of excited elegy in the way Irish and Spanish can.’ [xxi]; speaks of Paul Durcan and Gerry Murphy as having learned a great deal from Galvin’s methods; ‘He is a poet of troubled conscience, and many (especially later) poems, such as Folk Tales for the General” bear witness to this: however, there is another Galvin which is wonderfully indifferent to conscience and its troubles. This is the one we see traces of in “The White Monument”, which celebrates the sheer energy beyond our judgement, of a powerful personality.’ [goes on to cite “My Little Knife”, a poem compared with Yeats’s Crazy Jane sequence; ‘This is the real thing.’ [xiii]; highlights “The Kings are Out”; notes workings of ‘a kind of appalled conscience’ in Belfast poems such as “Midnight”; and “Troubles”; compares the ‘enigmatic situation ... in a kind of skeletal folk tale’ of these with work of Pablo Neruda and Gabriel Garcia Marquez; ‘Galvin is a pet who combines a very strong sense of the community that shaped and formed him, and gave him his voice, with a broad sense of human concerns, that range from social idealism through pity for the victims of power, to anger at wrongs done. In spite of this alert and engaged conscience, however, his verse also celebrated the energy which his indifferent to our moral conscience and conscientious objections.’ [&c.; xvi.]

Shirley Kelly, ‘The brutality of that place I’ll never forget’ [interview with Patrick Galvin], in Books Ireland (Feb. 2003): Galvin son of mostly unemployed dock-worker in Cork, with four brothers and three sisters, now mostly lost in diaspora; his mother a supporter of the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War; a maternal grandfather shot dead in Chicago bootlegging wars; other eccentric relatives; sent as teenager to reformatory (‘My parents couldn’t make any hand of me’; I was out of control […]’); Song for a Raggy Boy set in fictional St. Jude’s; ‘mindless beatings and the most sadistic punishments’; arrival of new English teacher William Franklin, returned from Spanish Civil War, introduces interest in literature and encourages literacy among the boys; later died at Normandy; Galvin travelled to Belfast to join American forces but accidentally recruited to the RAF ‘by mistake’ and became bomb-loader, serving in Britain, North Africa, Palestine and Sierre Leone; settled in London; read poems on BBC; married with two daughters and separated; issued 7-disk set of Irish ballads of 1798-1923; returned to Belfast and ultimately to Cork with his second wife, 1996. (pp.5-6.)

[ top ]

|

|

John Masterson, ‘For the raggy boy comes literary riches’, in Irish Independent (26 Jan. 2003)

|

Talented writer Patrick Galvin tells John Masterson how his life story informed his books WOMEN have played a big part in writer Patrick Galvin’s life. As a teenager in Cork he was in love with films and film stars and Betty Grable, well, her legs really. They were enough to get him to go to war ...

|

“That was lust more than patriotism. I didn’t intend to join the RAF. I wanted to join the American army because I was fascinated by the poster of Betty Grable stretched out on the fuselage of a bomber and underneath it said ‘come fly with me’ and I thought, Jesus, I’m with you girl, all the way!”

And off he went with that sceptical offbeat view of life that peppers his writing and made the first part of his autobiography Song for a Poor Boy such a cult hit.

“I probably got it from my mother. She was very socially conscious and she wouldn’t believe anything unless it was in front of her.”

Born in 1927 Patrick grew up in crushing poverty in Cork city. And with massive unemployment mothers were important.

“She was the boss of the family. There were a lot of women like that around. Because the old man wasn’t working they had to take over the house, plucking chickens while the old man was on the dole. We were poor, but I never realised that until many years later when I went abroad. My old man brought up six children on 20 shillings a week on the dole. We were always broke, especially when he was on the drink and then he gave up the drink and got all religious. My mother used to say ‘for Jesus sake would you go back on the drink’!” His mother and father were devoted but, politically, poles apart. He was a Free Stater and she was totally anti. And those things mattered and soured the marriage in later life. And his mother held a secret which he only learned long after her death.

“This bloke came up to me after a reading and said ‘by the way, my mother asked me to give you this if I ever came across you’. It was a photo like they took of weddings in the old days and I looked and saw my mother. And he told me that the guy was his grandfather and the woman his granmother. My mother had been married before, this was my nephew, by a half sister that I never knew I had. Jesus, that was a surprise to me. I went to see her marriage cert and she had written ‘spinster’ and it was crossed out and ’widow’ written in.” Patrick had an appetite for trouble and his time in a reformatory in Daingean, Co Offaly, where he spent three years, make up the second part of his trilogy, and the screenplay Song for a Raggy Boy which has recently been made into a film starring Aidan Quinn.

“The phrase was ‘beyond parental control’ and in a way they were right. I used to stay out all bloody night. I was great for arguing and I had run away a few times. The brutality in Daingean was unbelievable. I never came across anything like it and the obsession with sex. If two youngsters were seen to go to the loo together they were obviously up to something.” The punishment he describes with a leather strap embedded with coins to cut the skin makes chilling reading. He had always been cynical about religion but seeing it close up those years confirmed his atheism.

“Even as a young child I couldn’t believe in the one God that knew everything all the time. I called myself an atheist at about the age of 10. I didn’t know what it meant but I wasn’t in favour of the church. We were frightened of the church. The priest was more powerful than anybody.” The one good thing that happened to him in Cork was to meet an elderly Jew, Mr Goldman, who used to write letters for people. He took an interest in Patrick and read to him from books that gave him the hunger to learn. He also had a hand getting Patrick his first job as a messenger boy.

“He had this copperplate writing and would write a letter ... ‘Esteemed sir, I wish to apply for the post of ...’ and you would be in dread of your life that you would be asked to write when you got the job. I was too small for the bike. I was ten.’

Going to war and spending time in Africa was the making of him. Another soldier interested in reading kept his mind going. He saw bigotry and prejudice and his mother wasn’t far away when he saw at first hand ”the mania for Empire. The way they took if for granted that #145;India is ours’ and ‘Africa is ours’”’.

At each posting an officer would tell them where they would sleep, wash, eat, and where the brothel was. The latter did not interest him: ”partly from some kind of morality from my mother. And my father was in India and he used to tell us stories about people getting the pox and they didn’t send them home. They smothered them with two mattresses and sent a note to the relatives saying he died in action. Or so he said!”

The love of reading and writing had taken hold and Patrick is now a proud member of Aosdana with 10 stage plays, many radio plays and a fine body of poetry to his credit. It has been a colourful life and it makes for good conversation as he sucks on one cigarette after another. But then, it wasn’t all bad, and today is not all that much better. It’s how he sees it from the present perspective.

“I think we have lost a great deal of the community spirit there was then ... visiting each others houses and sharing what little we had. That sort of thing.” |

| [Note: The above text has been kindly supplied by Elli Sarantopolou via email- 30.01.2020.] |

|

[ top ]

| Irish Times notice of the death of Patrick Galvin, by Rosita Boland (11 May 2011) |

[...] In the 1960s, then archbishop of Dublin John Charles McQuaid was so exercised by Cry the Believers, a play about the Catholic Church, that he sent someone in secret to report back on it. “With its unending carping about the Church and the clergy0, the ensuing lengthy report concluded, it was not a play “to which young, impressionable minds could be exposed without risk to faith”.

|

| —Available [online]; accessed 03.03.2020. |

| Patrick Galvin: Irish poet and playwright whose Raggy Boy memoir of his grim and violent youth in a reformatory school was made into a film:

Obituary Notice by Donna MacBride, in The Times (13 May 2011). |

|

Already a leading Irish poet and playwright, Patrick Galvin gained unexpected international fame when a section of his 1990 autobiography, The Raggy Boy Trilogy, was made into a feature film, Song For a Raggy Boy (2003), starring Aidan Quinn and Iain Glen. A dark and brutal film, which won a host of awards, Raggy Boy is the story of Galvin’ s early adolescence in an Irish reformatory school run by the sometimes sadistic Christian Brothers. The son of a docker, Galvin grew up in extreme poverty in Cork city in the early 1930s and first came to prominence with his powerful long poem Heart of Grace (1957), an account of the brutalising of a young boy at borstal, which was widely praised by critics including Edwin Muir and A. Álvarez. As one of the few 20th-century Irish poets of working-class origin from before the advent of free secondary school education, his poems recount the experience of the Irish urban poor like no others.

After leaving reformatory school Galvin sold sheet songs and ballads in the streets of Cork, worked as a messenger boy and also as a cinema projectionist. He joined the RAF under age, using his brother’ s birth certificate, and served in Sierra Leone, the Western Sahara and Palestine. After the war he settled in London and began writing poems and songs. He recorded seven LPs of Irish ballads and numbered among his friends Ewan McColl, Brendan Behan and Dylan Thomas. His most famous song, covered by Christy Moore, recounts the execution of James Connolly. All his later dramatic and poetic work drew heavily on his experience as a ballad singer and his knowledge of Irish music.

His first play, And Him Stretched, a political drama, was staged at the left-wing Unity Theatre in London and then at the Dublin Theatre Festival where it won the Best New Play award in 1962. A year later he followed it with the controversial Cry the Believers which won Play of the Year again at the Dublin Theatre Festival. Dublin audiences were shocked by a scene where the Irish flag is torn in two. “Frank O’ Connor hated it,” recalled Galvin, “and Siobhan McKenna said she couldn’t believe what was happening on the Irish stage even though she hadn’t seen it. We were sold out for weeks.”

In the mid-Sixties and early Seventies Galvin wrote several more books of verse, notably The Woodburners (1973). Dublin, Belfast and Cork are mentioned in Galvin’ s poems, but it was Cork and the people of Cork that always gripped his imagination. The Mad Woman of Cork (1973) became one of his best known poems and was widely translated. In 1974 Galvin began a productive association with the Lyric Theatre in Belfast through a Leverhulme fellowship in drama. Under the direction of Mary O’Malley, he brought to the stage The Last Burning, a play about the last witch to be burnt in Ireland, Nightfall to Belfast, and the musical drama about the troubles We Do it For Love (1975). Playing small roles in the musical were Liam Neeson and Gerard Murphy, both then unknown. The Lyric Theatre came under attack during Galvin’ s residence. When Nightfall to Belfast was staged, a 200lb bomb exploded directly outside the theatre, destroying the director’ s car. “Fortunately no one was killed. Authors may deserve to be shot or blown up, but they shouldn’ t involve people,” Galvin reflected.

Throughout much of his career he attracted — some say courted — controversy. In the early Fifties he sparred with Sean O’ Casey in a series of letters to John O’ London’ s weekly. O’ Casey refers to Galvin spikily in his autobiography. In the Sixties Galvin sacked his literary agent, the celebrated Margaret Ramsay (“She was hopeless,” he said) and in 1976 he publicly disowned his own play The Devil’ s Own People, in an irate letter to The Irish Times. The work, which was running at Dublin’ s Abbey Theatre, starred Ray McAnally who reputedly excised Galvin’ s use of the F-word from the script each night. Galvin was also in demand as a director and directed several of Samuel Beckett’ s plays at the Lyric Theatre, Belfast and a British tour of The Importance of Being Oscar, starring Bryan Johnson in 1988.

He toured extensively around the world, particularly in Mexico and Canada, giving poetry readings and was a noted orator. He had a strong interest in Spanish culture and for several years lived in Spain. His later work, including Folk Tales from the General (1989), show the influence of Federico Garcia Lorca and other Spanish Surrealists. In 1984 he was elected to Aosdána, Ireland’ s elite creative arts body, and in 1994 he received the O’ Shaugnessy Award for Poetry. The same year he settled permanently in Cork and became resident writer at Cork University which published his Selected Poems. He suffered a major stroke in 2005 but continued to write.

A poet and playwright who combined a strong sense of the community that shaped and formed him, Patrick Galvin was one of Ireland’ s most distinctive and original writers, a master of understatement who combined black humour with intense compassion. He was married four times and had two daughters and three sons. [End; reparagraphed here.]

|

| —Obituary, The Times (13 May 2011) - available online; accesssed 10.01.2020. |

|

[ top ]

Roger Sansom, letter to The Times (17 May 2011): ‘Roger Sansom writes: Your obituary (May 13) of Patrick Galvin, Irish poet and playwright, does not mention that one of his sons was Patrick Newley, writer, raconteur, biographer of Douglas Byng and Mrs Shufflewick, who died in 2009. Patrick Jr had changed his name to Jack Newley, and then Patrick Newley. Curious about how Patrick Sr felt regarding a son, namesake and fellow-writer whose concerns in life were so different, I mentioned on meeting him at a Belfast party that I “knew Patrick — or rather I know him as Jack”. The father replied “Ah, yes. Jack.” And that was as much as I learnt.’ (See “Remembered Lives”, in The Times (London)- 17.05.2011 - online; accessed 10.01.2020.)

[ top ]

| Patrick Galvin (15 Aug. 1927-10 May 2011) - an Irish poet, singer, playwright and prose & screen writer: Alcethron Encyclopedia. |

|

Galvin was born in Cork in 1927 at a time of great political transition in Ireland. His mother was a Republican and his father a Free Stater which gave rise to ongoing political tension within the household and later informed his well loved poem “My Father Spoke with Swans” and his autobiographical memoir Song For a Poor Boy. An autodidact, he came to know and love literature through the Russian, French and Irish classics. His early poetry shows the influences of Gaelic poetry whilst his later poetry reflects more international rhythms and themes. He had grown up during the time of the Spanish Civil war under the shawl of his mother’s Republican politics and later discovered a great affinity with the Andalusian poet, Federico García Lorca; these influences are evident in his epic poem about Michael Collins, “The White Monument”. His childhood ended dramatically when he was sent to Daingean industrial school, noted for its abuse of young people in its care. This experience had a powerful influence on his earlier poetry which expresses the fear and brutality of that time:

In his prose memoir Song For a Raggy Boy he contextualises those experiences within the Europe of the second world war. Irritated by Ireland’s neutral stance he joined the Royal Air Force in 1943. His anti-war memoir Song for a Flyboy from 2003 records his war experiences and his play The Devil’s Own People from 1976 denounces Ireland’s neutrality in the face of fascism and the Holocaust.

After the breakdown of his first marriage, at the age of 21, he went on to establish himself as a folksinger, song writer and collector, recording nine volumes of folk songs as well as publishing Irish Songs of Resistance 1798 -1922. He travelled widely during this period going behind the ‘Iron Curtain’ to East Germany as a troubadour. These experiences marked his work and his personal life. He began to publish poetry in many leading English and Irish journals and he co-founded and edited the literary magazine Chanticleer. His first collection of poetry Heart of Grace, 1957 was closely followed by the second Christ in London, 1960 . At that time he was also in the process of establishing himself as a playwright in London and Dublin where his work was closely monitored by the Catholic Church hierarchy in Ireland, which found that his play Cry the Believers was not one ‘to which young, impressionable minds could be exposed without risk to faith’. He was given the reputation of being the ‘Enfant terrible of the Irish Theatre’ by one Irish critic. He came back to Ireland in the 1960s but, unable to adapt to the conservatism of that time, he returned to London and spent intervals abroad in Israel.

In 1973 he returned to Ireland, this time to Belfast as Writer in Residence at the Lyric Theatre. It also saw the publication of his third collection of poetry The Woodburners. That period of time with the Lyric Theatre established Galvin firmly as an exciting dramatist. His groundbreaking play We Do It For Love (the first satire about “the Troubles”) broke all box office records for an Irish play at the Lyric. Through his work there he was influential in inspiring a new generation of writers in the north of Ireland. His final play at the Lyric, My Silver Bird, was an operetta based on the life and times of Grace O’Malley, dramatically culminating in the battle of Kinsale and the fall of the Gaelic order. The score was composed by Peadar Ó Riada. The play was first staged the night after Bobby Sands died and due to the prevailing political climate it was prevented from travelling to and showing at Cork Opera House as scheduled.

Galvin later went to live in Spain where he completed his fourth collection of poetry Folktales for the General. He returned to Cork in the 1980s and he began to work on his memoirs Song for a Poor Boy, Song For a Raggy Boy and Song for a Flyboy. In 1997 he wrote the screen play for Song For a Raggy Boy which got its world premiere at Cork Film Festival in 2003. Patrick was Writer in Residence with East Midlands Arts (UK), Dun Laoghaire Rathdown Council, Portlaoise Prison and finally with University College, Cork, where he was awarded a Doctorate of Literature in 2006. Galvin cofounded the Poetry Now Festival, which went on to become Ireland’s leading poetry festival. With his wife Mary Johnson he co-founded the Munster Literature Centre in Cork which has given birth to the Frank O’Connor Festival and to the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, one of the largest in the world.

Throughout his life he has adapted his own work and other works for both BBC radio and RTÉ radio. He travelled widely giving readings of both his prose and poetry, much of which is recorded in the Library of Congress in Washington. In 1984 he was elected to Aosdána. Patrick suffered a stroke in 2003. In spite of this, in 2005, the year of the City of Culture Cork, he co-translated the collection of poetry Everything But You from the original poetry of Turkish poet Yilmaz Odabashi. Latterly the constraints of his lengthy illness and his inability to give creative expression to his thoughts on the current state of Ireland, with its culture of greed, exploitation and refusal to deal with systematic physical and sexual clerical abuse, contributed greatly to his demise. He was survived by his daughter Grainne and son Macdara from his marriage to Mary Johnson and his daughter Christine Bygraves from a previous marriage. His widow Mary Johnson died a few months after his death. He was predeceased by his oldest son Patrick Newley in 2009.

|

| —Alcethron Encyclopedia - online; accessed 10.01.2020 [ photo-port. as supra; reparagraphed here. |

|

[ The Irish Times obituary is by Rosita Boland - online; accessed 10.01.2020. ]

|

| Patrick Galvin at his last birthday, 2010 |

|

|

‘Patrick Galvin: ‘Renowned poet and socialist’ [obituary] - Workers Solidarity Movement (10 May 2019)

|

|

Patrick Galvin, the renowned Cork writer and socialist, has died. Born in Margaret Street in Cork in 1927, Paddy was a prodigious and accomplished writer producing many works in poetry and drama, as well as writing the memoir The Raggy Boy Trilogy. He was also a most accomplished balladeer and many of his early works were in this form.

Galvin’s early life was spent in and around the Barrack Street area of Cork - a place that he described as ‘desperately poor’ but ‘highly atmospheric’. Following charges of ‘being disruptive’ he was sentenced in the 1930s to a term of three years at St. Conleth’s Industrial School in Co. Offaly - an experience that was to mark him hugely and make him into the lifelong socialist and an advocate for the oppressed. On his return to Cork, following this harrowing experience, he worked as a newspaper boy, a messenger and as a projectionist at Cork’s Washington Street Cinema. In 1943, using a forged birth certificate, he went to Belfast and joined the RAF at the age of sixteen. Following service during WW2, he was demobilised and worked in London at various odd jobs. He later travelled around Europe.

He began writing poetry, by his own admission, in the late 1940s. However under the influence of Seamus Ennis, the traditional uileann piper, he first made his mark as a folk singer going on to record over 7 LPs of songs and ballads. Among many fine compositions, there is of course his renowned version of “James Connolly”, a song later popularised by Christy Moore.

Patrick Galvin’s first book of poems - Heart of Grace - was published in London in 1957. He later went on to produce Christ in London (1960), The Wood Burners (1973), Man On The Porch (1979) and Folk Tales for the General (1989). New And Selected Poems (1996) established his position as a major poet of his generation. In the introduction to this work he was described as “a poet who combines a very strong sense of the community that shaped and formed him, and gave him his voice, with a broad set of human concerns that range from social idealism through pity for the victims of power, to anger at wrongs done”.

Galvin was also a very fine dramatist. He wrote and produced many works for, among others, the Lyric Theatre and the BBC. He also worked on many adaptations for the BBC and also as a writer in residence in England, Ireland and in Spain. In the 90s he returned to Cork and played a pivotal role with Mary Johnson, his partner with whom he had two children, in establishing the Munster Literature Centre in Cork. In 2003 with his reputation on the rise he was struck down by a debilitating stroke. He survived and recovered with the loving support of his family but his ability to continue writing was severely curtailed - a factor which was to become a huge burden for him.

Patrick Galvin was angered by the publication of the Ryan Report in 2009 into the abuses at the Irish Industrial Schools. Not only did the Report remind him of his own period of incarceration, it also reminded him of the reality that he was one of the first to speak out about what was going on in these institutions - and was pilloried for doing so. He had always been incensed at the vile and cruel abuses that went on in these institutions, and had long contended that they had occurred under the ever watchful and approving eye of the Irish State and the Catholic Church.

In an ironic testament to his lifelong commitment to socialism Patrick Galvin spent nearly twenty hours waiting on a hospital trolley at CUH (in Cork) on what was to be the last weekend of his life - this weekend just gone. Despite receiving excellent care he died peacefully at CUH late last night. He will be remembered not only for beautiful and evocative writing, but also for his opposition to capitalism and his lifelong commitment to struggle for a just workers society.

Reposing at Connolly Hall tomorrow, Thursday, from 4pm until 8pm (May 12th), fittingly, on the anniversary of the execution of James Connolly. Cremation on Friday at 2pm at the Island Crematorium, Ringaskiddy.

|

| —Available online (accessed 14.04.2019) - with links to James Connolly and to the Ryan Report. |

|

[ top ]

Quotations

| The White Monument (poem on Michael Collins) |

Come fifteen now, the flogging belt, the prison cell,

The cruel days, the friendships hanged and cold,

The dead beat of winter and the hungry bell,

The very young are battered and grow old.

And every day they stand about and watch and stare,

The shaven heads, the broken ribs, the iron rod.

And every night they weep an empty eye

And curse the hand that killed Almighty God. |

—Given in Wikipedia entry - online; accessed 10.01.2020. |

|

| The Prisoner of the Tower |

I can see them now

Prisoners of the tower

Their faces blind

From centuries of barbed wire.

If you are guilty

You know you are guilty

If you are innocent

You would not be here.

You are here

Therefore ...

1

When the cell door closes

Behind you

You are free

When the cell door closes

Behind you

You are free

When the cell door closes

Behind you

You are free to weep

Endlessly

Without tears.

It is an offence

To shed tears in the tower

It is an offence

To grow old in the tower

It is an offence

To sit in the tower

But

You may walk freely

From wall to wall

And contemplate

The absence of bread.

Under our system of Government

A man has these rights:

You may walk freely from wall to wall

And contemplate the absence of bread.

2

You may not

Hear voices.

All prisoners

Who hear voices

Will report such voices

To the Keeper of the tower.

These voices do not exist

And if they do exist

They will be shot.

The shooting of voices

Is essential

To the harmony

Of the tower.

|

All prisoners

Who fail to report

The hearing of voices

Will be shot.

All prisoners

Who report the hearing of voices

Will be sent to a lunatic asylum.

Prisoners who are sent to a lunatic asylum

May

Lose the freedom of the tower

But the voices will stop.

Under our system of Government

A man has these rights:

You may lose the freedom of the tower

But the voices will stop.

3

You are free

To die.

All prisoners

Are entitled to death

All prisoners

Are entitled to a speedy death.

Any prisoner

Who is not capable of committing suicide

Will be shot

Any prisoner

Who fails to report

A desire to commit suicide

Will be shot.

When a prisoner dies in his cell

His body will remain in his cell.

It is an offence

To remove the dead from their cells.

It is assumed that in due time

Nature will corrupt the flesh

But the bones

If any

Remain the sole property of the prisoners.

He may return for these bones

At any time.

Under our system of Government

The dead also have rights:

You may return for these bones

At any time.

You are free

To have them. |

| —1979, Patrick Galvin, from New & Selected Poems (Cork UP 1996) - Poetry Foundation online; 10.01.2020. |

|

[ top ]

References

Brian De Breffny, ed., Cultural Encyclopaedia of Ireland, contains a short entry: ‘his genius and pieties inseparable from his birthplace, Cork.’

Robert Hogan, ed., Dictionary of Irish Literature (1979) describes his verse as ‘vigorous slabs of language rather than poetry’, and characterises his Belfast plays as ‘thin stuff’.

[ top ]

Notes

Translation Cork: Cork poets incl. Bernard O’Donoghue, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Theo Dorgan, Greg Delanty, Robert Welch, participated in Cork 2005 European translation series directed by Pat Cotter of the Munster Literature Centre.

Burning Question: Galvin’s play of 1974 is variously described as being based on the story of Brigid Cleary and on the Dame Kyteler witch trial in Kilkenny.

Birth date: either April 15th or August 15th, 1927 or possibly 1929 or later. Galvin’s date of birth remains uncertain as his mother changed the date on his birth certificate so that he could more easily find employment. (See Galvin page at John Burns Library, Boston College - online.) It is also unclear from reference sources [supra] how long he remained in Daingean and whether the influential teacher was a member of staff there.

Raggy Boys: In the autobiography (Song for a Raggy Boy), the boy Mercier is not killed by the Christian Brother as he is in the film. On being contacted by Elli Sarantopolou, the director Aisling Walsh said that his death was only a creative liberty she took - just to show that murders did happen in these institutions. (Email from Eli Sarantopolou, 12.03.2020.)

Munster Writers: Patrick Galvin appeared in In the Hands of Erato - a documentary produced and directed by Liz O’Donoghue for Munster Arts Centre in 2003 - reciting his poetry likewise featuring Greg Delanty, Thomas McCarthy, Patrick Cotter, Conal Creedon, Trevor Joyce, Theo Dorgan, Louis De Paor, John Montague, Roz Cowman, Robert O’Donoghue, Rosemary Canavan, Gerry Murphy, Gregory O’Donoghue, Aíne Miller and Liz O’Donoghue. Original music and soundtrack by Martin Moylett. Camera, sound and editing by Dave Whelan. Additional editing by Neil Patrick McCarthy. Copyright held by Liz O’Donoghue. (Aug. 2018).Available at YouTube - online; accessed 19.08.2024.)

[ top ]

|