|

Frank Harris, The Bomb (1908) and Sundry Commentaries

[Note: the following records of commentary and criticism were collected on Internet in July 2018 by BS.]

|

|

Commentary on The Bomb (1908)

|

| Leah A. Zeldes, Reader-Review of The Bomb, at Manybooks.net |

A stirring, fictionalized account of the Haymarket Affair in 1886: In the wake of a deadly strikebreaking incident when Chicago police fired into a crowd of unarmed workers, labor leaders organized a meeting on May 4 near Chicago’s Haymarket Square. Denouncing the police attack, speakers urged workers to increase efforts toward an eight-hour workday and an end to child labor. Chicago Mayor Carter H. Harrison, who attended the rally, told police not to disturb the peaceful protest, already beginning to disperse due to rain. Nevertheless, once the mayor left, armed police threateningly ordered the remainder to disperse, using clubs for emphasis. In the mêlée, somebody threw a bomb, which resulted in the death of one policeman. Six others were killed by subsequent gunfire, mostly proved to be from police pistols.

Afterward, capitalist-controlled, fearmongering newspapers whipped up public terror with unsubstantiated stories of anarchist conspiracies and bomb making, attacked immigrants and called for revenge. Police arrested hundreds of people, but never determined who threw the bomb.

Finally, in what was afterward considered one of the worst miscarriages of justice in American history, eight men, prominent socialist and anarchist speakers and writers - Louis Lingg, August Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer, George Engel, Samuel Fielden, Oscar Neebe and Michael Schwab - were tried for murder. Prosecutors presented no credible evidence that any the defendants threw the bomb or knew of it, and several weren’t even there. The judge showed evident bias and the 12 jurors had all acknowledged prejudice against the defendants, and all eight were convicted and seven sentenced to death.

The trial was thought so iniquitous that the next governor of Illinois pardoned the three defendants still living. Four of the men had already been hung, and Lingg had defiantly blown his head apart in jail.

Harris’s novel clearly sides with the labor and anarchist cause, but follows pretty closely the facts as they emerged after the trial. The story is narrated by Rudolph Schnaubelt, an anarchist who escaped arrest and disappeared but was thought at the time to be the probable bomber. He makes Lingg, the youngest and most dramatic of the anarchists, the central figure of the story.

The novel starts with Schnaubelt recounting his boyhood and education in Germany, his emigration to the U.S. the subsequent hardships and struggles to find work at a living wage that drew him to the radicals’ cause. He talks of his own and others’ maltreatment by employers - people maimed for life or killed by unsafe working conditions without recompense. Interspersed with his stories of what led up to the fatal day and its aftermath, he also describes his love affair with a young woman whose views of the world seem at odds with his own.

The biggest defect is that Harris makes the anarchists seem a little too good to be true, but that’s nothing given the essential truths he covers. Everyone who looks at America today will find recurring echoes of the class struggles of the 19th century. (Manybooks - 2015.05.02)

|

Available at Manybooks.net - online; accessed 02.07.2018.) |

| |

| Cf. the contemporary review in Book Review Digest (1909) |

Frank Harris’ fictional account of the Haymarket Affair of 1886 focuses on Rudolph Schnaubelt, a German immigrant whose socialist background, discontent with his chosen country, and hatred for authority lead him to join the Chicago anarchists during the labor unrest of the 1880s. When strikes at the Pullman and McCormick plants and discontent among the stockyard employees and other workers throughout the city culminate in public demonstrations and riots which Chicago police attempt to control, it is Rudolph Schnaubelt who sets off a bomb killing eight policemen and injuring sixty people at a rally in Haymarket Square. The story is told in the first person, as seen through the eyes of Schnaubelt, who escapes to Bavaria where he watches closely the events which follow in the wake of his action. The Bomb is a depressing book on an ugly subject. Even an attempt by the author to relieve the demoralizing influence of the novel through the addition of a romantic sub-plot does little to alleviate the total starkness of the story and the writing.

|

Available at Manybooks.net - online; accessed 02.07.2018.) |

| |

|

Guido Bruno, on Frank Harris, The Bomb - in Bruno’s Weekly, Vol. 3, No. 23 (22 November 1916)

|

|

|

|

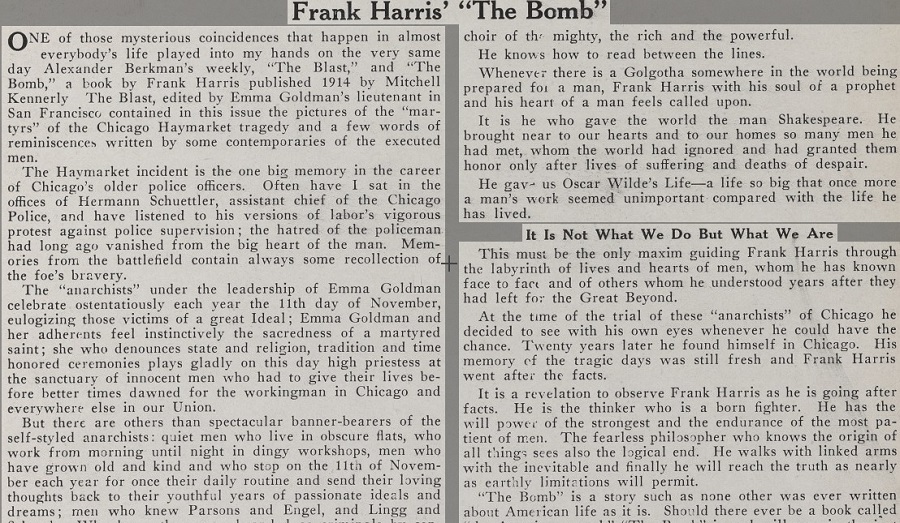

One of those mysterious coincidences that happen in almost everybody’s life played into my hands on the very same day Alexander Berkman’s weekly, The Blast, and The Bomb, a book by Frank Harris published 1914 by Mitchell Kennerly. The Blast, edited by Emma Goldman’s lieutenant in San Francisco contained in this issue the pictures of the “martyrs” of the Chicago Haymarket tragedy and a few words of reminiscences written by some contemporaries of the executed men.

The Haymarket incident is the one big memory in the career of Chicago’s older police officers. Often have I sat in the offices of Hermann Schuettler, assistant chief of the Chicago Police, and have listened to his versions of labor’s vigorous protest against police supervision; the hatred of the policeman had long ago vanished from the big heart of the man. Memories from the battlefield contain always some recollection of the foe’s bravery.

The “anarchists” under the leadership of Emma Goldman celebrate ostentatiously each year the 11th day of November, eulogizing those victims of a great Ideal; Emma Goldman and her adherents feel instinctively the sacredness of a martyred saint; she who denounces state and religion, tradition and time honored ceremonies plays gladly on this day high priestess at the sanctuary of innocent men who had to give their lives before better times dawned for the workingman in Chicago and everywhere else in our Union.

But there are others than spectacular banner-bearers of the self-styled anarchists: quiet men who live in obscure flats, who work from morning until night in dingy workshops, men who have grown old and kind and who stop on the 11th of November each year for once their daily routine and send their loving thoughts back to their youthful years of passionate ideals and dreams; men who knew Parsons and Engel, and Lingg and Schwab. Who knew these men branded as criminals by contemporaries, hung as foes of the Commonwealth, who knew them to bo pure in their hearts, kind to fellowmen with one big love for suffering wronged humanity.

They too had been contemporaries of the Haymarket tragedy. They had gone to all parts of the country and had carried to their new places of habitation loving memories of those men who had been the sacrifice offered for the coming of a better era.

I know one man in New York who knew the executed men all intimately, perhaps better than anybody else living. As he had been their daily companion for years before their death. He speaks of them as of those dearest loved.

I have often heard Mrs. Parsons talk of the life and the last days of her husband in Newberry Park, Chicago, right in front of the portals of the Newberry Library while her son was exhibiting the picture of his father to the crowds that had assembled quickly. Policemen do not interfere with her meetings and do not even prohibit her sale of the book she wrote, an account of Parsons’ life.

A loud and boisterous celebration of professional agitators did not impress me but the unimpassioned heart to heart talk with dozens of men, of contemporaries of the executed strivers for workingmen’s rights. All these told me of the great wrong that must have been committed by a prepossessed minority of potentialities to a majority in Chicago, to its laborers, in the name of Justice.

The master pen of Frank Harris immortalized in this case as in many other instances the innocent victims of prejudice and of power. His book The Bomb that came to me so many years after it had been written and by a strange coincidence on the 11th of November, erected an eternal monument for these men who had to die because they aimed at equality among men, because they fought against class distinction, against national hatred, and against the greediness of citizens who abused for their own purposes newly arrived immigrants, helpless in their lack of knowledge of English. They had to be the victims of this very same hatred. Frank Harris felt and feels always with his almost superhuman intuition where innocence suffers, when law is being misinterpreted, when freedom of mind and of body is being trampled upon.

In faraway England he had read the accounts of the Haymarket riots, distorted by a press only too ready to join the choir of the mighty, the rich and the powerful. He knows how to read between the lines. Whenever there is a Golgotha somewhere in the world being prepared foi a man, Frank Harris with his soul of a prophet and his heart of a man feels called upon. It is he who gave the world the man Shakespeare. He brought near to our hearts and to our homes so many men he had met, whom the world had ignored and had granted them honor only after lives of suffering and deaths of despair. He gave us Oscar Wilde’s Life - a life so big that once more a man’s work seemed unimportant compared with the life he has lived.

It Is Not What We Do But What We Are

This must be the only maxim guiding Frank Harris through the labyrinth of lives and hearts of men, whom he has known face to fact and of others whom he understood years after they had left for the Great Beyond.

At the time of the trial of these “anarchists” of Chicago he decided to see with his own eyes whenever he could have the chance. Twenty years later he found himself in Chicago. His memory of the tragic days was still fresh and Frank Harris went after the facts. It is a revelation to observe Frank Harris as he is going after facts.

He is the thinker who is a born fighter. He has the will power of the strongest and the endurance of the most patient of men. The fearless philosopher who knows the origin of all things sees also the logical end. He walks with linked arms with the inevitable and finally he will reach the truth as nearly as earthly limitations will permit.

The Bomb is a story such as none other was ever written about American life as it is. Should there ever be a book called “the American novel,” The Bomb is and will remain the just claimant to this title sought after so long now by pretenders from out of many camps. Louis Lingg and Rudolph Schnaubelt are the chief characters of the book. Both are Germans: the representatives of the two foremost types of German men, misinterpreted today as well as twenty years ago. So simple are they that they cannot be understood by their too complicated contemporaries; so sincere and true that they were and would be taken for quite the contrary.

Schnaubelt is the idealist. The doubter who accepts standards set bv his fellowmen, who goes his very own way but always tries to please others. He is proud - but not so above conventionalities as to abandon conventionalities. The spirit of 1848 is in his heart. Educated in Germany’s gymnasiums and University, a born writer, he arrives in America and goes the way so many thousands of others went; who perished and succeeded, went down and were never heard of or made their way and became the shining stars on our best Sunday firmament.

He went the way of a Carl Schurz.

He worked with shovel and pick. He met men as they are - he met the real American: the cosmopolitan who lost the narrow glories of national and of racial pride and who passed into the blessedness of love of man and of brotherhood of the universe.

Frank Harris calls it “the approaching kingdom of men on earth.” Schnaubclt is the German who has beautiful emotions in abundance: neighborly love, passion for one woman, compassion for fellowmen, ambition for himself. A healthy egotism compels him to seek after comforts and after the best this world can give.

But unknown to himself buried by all the important elements, the companions of his daily striving for earthly goods is the great characteristic of the German: his unbounded desire for freedom, indignation, rising whenever he sees other humans inhumanly treated, an indignation that rises to the Furor Teutonicus if he sees the knout on his fellowman’s neck brought down by a merciless slavedriver.

The German is capable of an almost unbelievable self-denial if it means the achievement of a big thing, especially if it be an abstract or ideal, or a protest against otherwise unchangeable accepted conditions.

Then all achievements of a lifetime are scattered to pieces, unmourned or even unnoticed. Worldly possessions, the love for the one woman, one’s future life is laid down upon the altar as a sacrifice.

No big words. No theatrically staged grand stands.

He simply gives. And the one who receives - and this seems as miraculous as the sacrifice itself - always knows the value of the gift.

And takes as it is given. Simply and bravely. The man who lays down his own life accepts the lives of others as seeming contributions toward the one big end.

Schnaubelt, I say, is the one representative type of the average German.

He sacrifices exultantly and dignifiedly everything, everything: Then he throws the first bomb that causes the great catastrophe - all the time acting under orders. First of all he considers carefully the cause, the end to be achieved. He makes up his mind that he wants to be instrumental in bringing about this end. He meets the man who seems to know the means to this end. He finds in him a man he honors and loves. Trust is established.

He joins the Cause. He is willing to be one of the means towards the end. Self-denial is victory after a hard and gruesome battle fought in one’s heart. The immediate members of one’s own small circle must be wounded, even though they be big enough to rise to the situation. After the Gethsemane comes the Calvary.

Schnaubelt resigns from his ambitions. He gives up the work that is daily bringing him nearer to pecuniary freedom, to his dearest dream[,] a home with Elsie. He, one of the kindest, one who could not hurt a man even with words, will throw a bomb that may kill thousands.

He will throw it at the command of Lingg.

Germans are either masters or obedient servants.

Schnaubelt is a servant. In Lingg he recognizes the master. He threw the bomb. His whole life seems to have had its purpose.

Blindly now he obeys his master. He follows him like a child out of the crow r ds to the depot. In the coach he breaks down mentally and physically - but he obeys his master. The master’s words are with him even after he has crossed the ocean to the safety of England.

“Write the true story of the Chicago tragedy,” is the master’s last command.

The world with its craving for sensationally theatrical bravery would have applauded Schnaubelt if he had followed his often almost maddening instincts, to go back to Chicago, to give himself up to the authorities, to walk into the courtroom and tell judges and jury: “All these men are innocent. There is Lingg! He made the bomb and here am I, who threw it!”

His self denial!

How much harder must it have been for the exiled man to obey the master’s command than it would have been to ascend with him the gallows - to die with him!

And Lingg!

Frank Harris understands this German as he has so many other people whom he gave newly born to the world.

Lingg represents the other type of the average German: quiet, kind, studious; unconfiding. He knows what he wants. He knows there are two ways to get it. At first he tries persuasion, education. He tries to evoke love with love. He tries to move men through their finest instincts.

He fails.

Brute strength, the power of an unjust tyranny are the weapons used by his unjust adversaries.

Lingg does not speak and does not implore any longer. He has realized that words will remain shallow. He considers more and more seriously the other way to his final goal.

The achievements of science in the hands of strong invincible determination must conquer brutal forces of unjust oppressors and unfair grafters.

He abstains from grandstand pleas. The world, its opinions and sympathies are naught to him.

Here is his path - there is his goal.

Obstinate masses, to their very own hurt, are obstacles in his path. But for them he could reach his goal. They must be removed. He proceeds to remove them.

No personal gain in view. Death is almost certain. If he succeeds or if he fails - but his great cause is eternal:

A better life among better people, love where there is hatred, a universal brotherhood where has been professed goodwill among their own clan only, among their own nation or their own race.

Frank Harris has made this man Lingg immortal.

We see Lingg’s bigness and we see his logical faults; we see his almost simple love of the average family man, and his utter disregard of persons and of his own self if it means to gain freedom for the world from slave-drivers.

He is the leader who serves his cause, who tells in clear words what he wants; he throws into the faces of his judges and of his jury, portraits of their own characters that make them tremble in their weak hearts.

Here is Lingg’s last speech after he had been found guilty and had been asked if he had anything to say as to why he should not be hanged:

“I had intended to defend myself; but the trial has been so unfair, the conduct of it so disgraceful, the intent and purpose of it so clearly avowed that I will not waste words. Your capitalist masters want blood; why keep them waiting?

“The rest of the accused have told you that they do not believe in force. I may tell you that they have no business in this dock with me. They are innocent, everyone of them; Ido not pretend to be. I believe in force just as you do. That is my justification. Force is the supreme arbiter in human affairs. You have clubbed unarmed strikers, shot them down in your streets, shot dov:n their women and their children. So long as you do that, we who are anarchists will use explosives against you.

“Don’t comfort yourselves with the idea that we have lived and died in vain. The Haymarket bomb has stopped the bludgeoninas and shootings of yoiir police for at least a generation. And that bomb is only the first, not the last. ...

“Now I have done. I despise you. I despise your society and its methods, your courts and your laws, your force - propped authority. Hang me for it!"

Then Linger died by his own hand! One day before his comrades were condemned to mount the gallows. He was the leader in life, a few steps ahead of his soldiers, the first one in dangers that be encountered; he is now the first one to vanish the dark depths where souls are stript of bodies.

The high explosive he had used against the adversaries of his cause he used on his own body. His earthly form was torn to miserable shreds. Lingg’s soul seemed to have thrown Lingg’s body contemptuously at the feet of the cagers: the hangmen, the judges, the jailers and the jurors.

The master had died. In a faraway country the disciple had carried out the master’s command.

Frank given America its great novel. The spirit of the book is tmly American.

It despises despotism and iniquity with the vigor of the men who exchanged their lives for freedom and independence from the English yoke: their lasting inheritance to us.

It pictures the petty graft in labor circles as it prevails todav as well as a score of years ago. It pictures the attitude of laborer and of authoritv during strikes true todav as in 1885.

It gives us the significance of these martyrs for truth and freedom as we never could gather it from professional agitators, who seem to have taken possession wholly of a legacy left to our country.

The deaths of these men were not in vain. Our labor legislatures have reconciled the laborers for iniquities of past years.

Frank Harris has erected a monument to the pioneers for equality among American laborers; to the sacredness of human rights that has never been violated in America without vigorous protest, a monument to the eternal contempt of brutality and despotism wherever the stars and stripes wave over the heads of man.

The sins of the fathers have been expiated by the sons.

Love has proved mightier than hatred.

Frank Harris preaches through the truth of his Bomb the near approach of his "kingdom of man on earth" in America.

|

Bruno’s Weekly (22 November 1916) - in Blue Mountain Project: Historic Avant Garde Periodicals for Digital Research [website]; accessed 03.07.2018. |

|