Life

1821-97; b. 21 Dec., Co. Carlow, son of Unitarian, formerly Quaker, who supported Fr. Theobald Mathew, vegetarian and anti-slaver; grad. TCD, 1843; elected fellow, 1844; orders, 1847; appt. chair of Geology, 1851; grad. medicine, TCD 1862; appt. Register of School of Medicine, and later rep. TCD on General Medical Council, 1878; elected to Royal Society, 1858; later awarded DCL of Oxford, and LLD of Cambridge and Edinburgh; prolific scientific author in geology and other subjects; contrib. to debate on Irish University Question, opposing secularisation of TCD and unified Irish University (i.e., National University of Ireland) - hence promoting Catholic University for Catholic students;

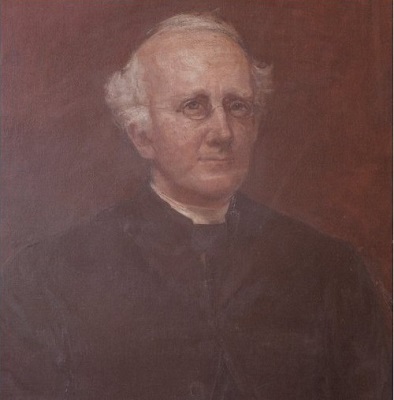

his areas of scientific research included the motion of solid and fluid bodies, solar radiation, climatology, animal mechanics, and ocean tides.Haughton calculated the optimum weight-distance ratio for hangman’s rope (known as ‘standard drop’), publ. as ‘On Hanging Considered from a Mechanical and Physiological point of view’, 1866; he was elected Pres. of RIA, 1866-91; accredited with building trains for first Irish railway service; gave Croonian lecture of Royal Society, 1880; gained notoreity by dismissing Darwin’s evolutionism in Irish Geological Society, Feb. 1859; his commissioned portrait by Sarah Purser hangs in the RIA, Dawson St., Dublin.

|

|

|

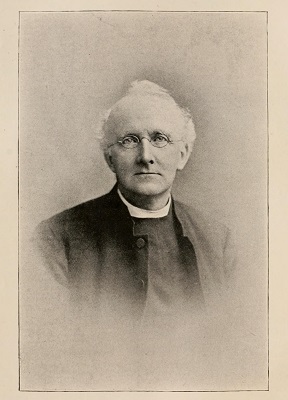

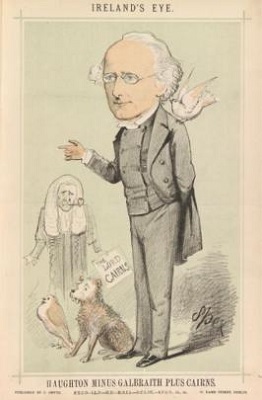

| Haughton in 1898 | Portrait by Sarah Purser (RIA) | Carton in Ireland’s Eye |

[ top ]

Works

University Education in Ireland, by the Reverend Samuel Haughton, M.D., F.R.S., [...] [Dublin: Printed at the University by M. H. Gill] (London: Williams & Norgate; Dublin: McGlashan & Gill 1868), 18pp. [see extracts]; ‘On hanging considered from a Mechanical and Physiological point of view’, in The London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 32, 213 (July 1866), pp.23-34.

The long drop: Haughton’s formula for the ‘long drop’ based on the equivalence with the energy of 1 ton falling through 1 foot: ‘Divide the weight of the patient in pounds into 2240 and the quotient will give the length of the long drop in feet’ - being a reference to the length of rope. Haughton’s ruminations on the subject included calculations of the method and force need to hang the unfaithful handmaids of Penelope who dallied with the suitors in the Odyssey [That’s Maths - online; accessed 26.11.2021.]

[ top ]

Quotations

University Education in Ireland, by the Reverend Samuel Haughton, M.D., F.R.S., [...] [Dublin: Printed at the University by M. H. Gill] (London: Williams & Norgate; Dublin: McGlashan & Gill 1868), 18pp. - see extracts:

| [...] Trinity College has never been, and never was intended to be, a national institution; her emoluments, her Fellowships and Scholarships, are the property of the Irish members of the English Church; and the proposal to throw them open to the competition of Roman Catholics and Dissenters is a proposal for the confiscation, so far, of the property of Irish Protestants. Trinity College has well and faithfully discharged the part she was required to fill; she has maintained the pure doctrine of the English Church against all opponents; she has reared her Students as faithful children of that Church; she has given them an education that enables them to compete successfully with all rivals in the walks of literature and science; and it cannot be fairly alleged against her as a fault that she has not provided for the educational wants of Irish Catholics; she was never intended to do so. The lovers of the gorgeous Rose need not blush because she wants the colour and grace of the beautiful Lily; and I may well be pardoned for believing that no brighter or fairer flower blooms in the garden of the West, than the Tudor Rose planted in Dublin by the proud Elizabeth. (p.7.) [...] The practical effect of secularizing Trinity College, if the experiment were successful, would be to convert it into a fourth Queen’s College, and it would thus become one of a class of Educational Institutions which the Church of Rome has always, and consistently, forbidden her children to enter. It is hard to see how such a plan as this can be rationally advocated, on the ground that it would satisfy the just demands of the Catholics of Ireland. So far, therefore, as Irish Roman Catholics are concerned, the secularization of Trinity College would be to them a loss, and not a gain; for it would transfer education in this College from the list of dangerous to that of prohibited enjoyments. [...] [The National University] would, however, in my opinion, be purchased at the cost of degrading for ever the standard of University Education in Ireland. If this objection can be established, it ought to have [10] weight in considering the question of Irish University Education. England differs essentially from Ireland, in affording to her young men countless openings in every walk of life, with or without the benefits of University Education, which in England may be regarded as a luxury enjoyed by the rich; whereas in Ireland an University Education is frequently a necessity imposed upon the sons of the less wealthy middle classes. The openings in life for young men of this class in Ireland are so very limited, that they must either emigrate, or rely on their talents and education, in pushing their way in the learned professions in England and the Colonies. Hence it follows, that any lowering of the standard of University Education in Ireland would be followed by peculiarly disastrous effects. At the present moment, Trinity College may be regarded as a manufactory for turning out the highest class of competitors for success in the Church, at the English Bar, in the Civil Service of India, and in the Scientific and Medical Services of the Army and Navy; and any legislation which would produce the effect of lowering the present high standard of her degrees, would tend to destroy the prospects of the educated classes in Ireland, and become to those classes little short of a national calamity. (pp.10-11.) [...] Having disposed of the first two schemes for satisfying the demand of the Irish Catholics for University Education, and shown one to be impolitic, and the other to be injurious, it might naturally be expected that I should now proceed to advocate the advantages of the remaining plan, which consists in a Charter and Endowment for a Roman Catholic University in Ireland, in which the Irish Catholics and their Clergy should be allowed to arrange their own programme of University Education without the interference of Irish Protestants, or of English doctrinaires; but this course I feel to be unnecessary, as it mainly concerns Roman Catholics themselves to state their wishes and explain their views respecting it. Protestant interference in such a question is as irritating and as useless as would be the interference of a mutual friend in a quarrel between a man and his wife. English politicians, in the matter of University Education for the Irish Catholics, have hitherto imitated the doctrine laid down by Mr. Bumble - that “the great principle of out-of-door relief is, to give the paupers exactly what they don’t want; and then they get tired of coming.” Twenty-seven out of twenty-nine of the Irish Catholic Bishops ask for a Catholic University Charter and Endowment, and are supported in this claim by an overwhelming majority of their flocks. The Irish Catholics asked the English Parliament for bread, and they gave them a stone: instead of a Chartered University, with a fair endowment and perfect freedom of Education, they received Queen’s Colleges, which were condemned as godless, and which they were prohibited by their Church from using. Let the Parliament of England for once try an experiment which will meet with the approval of Irishmen of all classes, and give to Ireland a third University, in [16] which the highest and best type of Catholic education shall be developed freely. Protestantism cannot suffer by the contrast, and education must certainly benefit. (pp.16-17.) [...] The milk-white Lily is not less beautiful than the crimson Rose; let them flourish side by side in the garden of Ireland. (p.18; end.) |

—See full text version in RICORSO Library - as attached. |

[ top ]

| P. W. Joyce, A Short History of Ireland from the Earliest Times to 1608 (1893) - writes of Haughton and Dr. Todd: |

|

| Joyce, op. cit., pp.222-23, ftn. 2. [available online; access date unrecorded.] |

Notes

The “death-drop”: R. S. Mackenzie, ed., Sketches of the Irish Bar, by Richard Lalor Sheil (NY 1855), gives a footnote account of hanging in Ireland in connection with the execution of John Scanlan, convicted of killing Ellen Hanley in the 1819 murder case which formed the inspiration of Gerald Griffin’s 1829 novel The Collegians:. See

| ‘It is considered in Ireland, that whoever lends or hires cattle or conveyance at an execution participates in the abhorred vocation of the hangman. Before the “drop” was invented, the condemned was usually conveyed to the gallows in a cart, sitting on his coffin — unless it were part of his punishment ..hat ‘his body be handed over to the surgeons for dissection.’ The finisher of the law, having adjusted the fatal rope on ‘the horse that was foaled of an acorn’ (see Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard), and round the neck of the doomed man, whom he placed standing in the cart, used to descend on terra firma, take hold of the horse’s head, draw away the cart, and thus give the death-fall to his victim. If any other person led the horse away, the disgrace of having virtually acted as executioner would cling to him through life. As I am on the subject, I may add that ‘Jack Ketch’ is a nom-de-corde used only in England. The Irish nick-name, no matter what the true appellation, is “Canty the hangman,” and the miserable wretch is compelled, out of regard for his personal safety, to reside n prison. If recognised out of doors, his life would not be worth half-an-hour’s purchase, so great is the popular detestation of his trade of legal murder. — M.’ |

| ‘Dying game’ [[page-header], in Sheil, Sketches of the Irish Bar (1855) - “An Irish Circuit” [being Chap. 1], p.53, n. |