Bret Harte, Gabriel Conroy (1875)

|

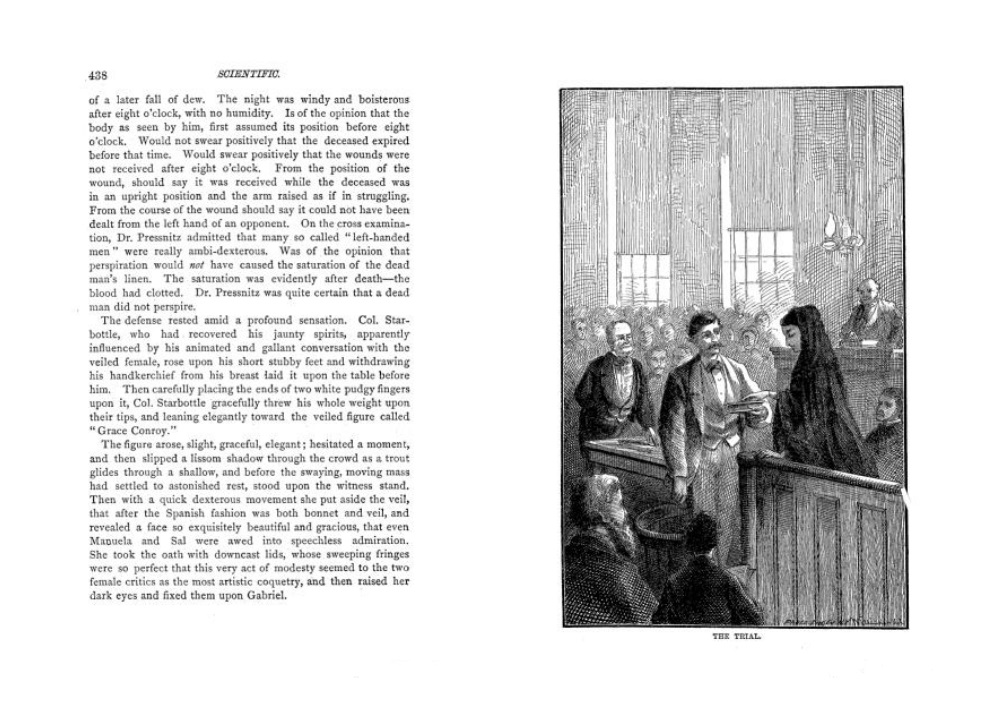

[p.1] Snow. Everywhere. As far as the eye could reach—fifty miles, looking southward from the highest white peak,—filling ravines and gulches, and dropping from the walls of cañons in white shroud-like drifts, fashioning the dividing ridge into the likeness of a monstrous grave, hiding the bases of giant pines, and completely covering young trees and larches, rimming with porcelain the bowl-like edges of still, cold lakes, and undulating in motionless white billows to the edge of the distant horizon. Snow lying everywhere over the California Sierras on the 15th day of March 1848, and still falling. It had been snowing for ten days: snowing in finely granulated powder, in damp, spongy flakes, in thin, feathery plumes, snowing from a leaden sky steadily, snowing fiercely, shaken out of purple-black clouds in white flocculent masses, or dropping in long level lines, like white lances from the tumbled and broken heavens. But always silently! The woods were so choked with it—the branches were so laden [p.2] with it—it had so permeated, filled and possessed earth and sky; it had so cushioned and muffled the ringing rocks and echoing hills, that all sound was deadened. The strongest gust, the fiercest blast, awoke no sigh or complaint from the snow-packed, rigid files of forest. There was no cracking of bough nor crackle of underbrush; the overladen branches of pine and fir yielded and gave way without a sound. The silence was vast, measureless, complete! Nor could it be said that any outward sign of life or motion {17} changed the fixed outlines of this stricken landscape. Above, there was no play of light and shadow, only the occasional deepening of storm or night. Below, no bird winged its flight across the white expanse, no beast haunted the confines of the black woods; whatever of brute nature might have once inhabited these solitudes had long since flown to the lowlands. [/1-2]; {1876/17} The starving members of the Captain Conroy’s Party: The language of suffering is not apt to be artistic or studied, but I think that rhetoric could not improve this actual record. So I let it stand, even as it stood this 15th day of March 1848, half-hidden by a thin film of damp snow, the snow-whitened hand stiffened and pointing rigidly to the fateful cañon like the finger of Death [3; 1875/19.] At noon there was a lull in the storm, and a slight brightening of the sky toward the east. The grim outlines of the distant hills returned, and the starved white flank of the mountain began to glisten. Across its gaunt hollow some black object was moving—moving slowly and laboriously; moving with such an uncertain mode of progression, that at first it was difficult to detect whether it was brute or human—sometimes on all fours, sometimes erect, again hurrying forward like a drunken man, but always with a certain definiteness of purpose, towards the cañon. As it approached nearer you saw that it was a man—a haggard man, ragged and enveloped in a [4] tattered buffalo robe, but still a man, and a determined one. A young man despite his bent figure and wasted limbs—a young man despite the premature furrows that care and anxiety had set upon his brow and in the corners of his rigid mouth—a young man notwithstanding the expression of savage misanthropy with which suffering and famine had overlaid the frank impulsiveness of youth. When he reached the tree at the entrance of the cañon, he brushed the film of snow from the canvas placard, and then leaned for a few moments exhaustedly against its trunk. There was something in the abandonment of his attitude that indicated even more pathetically than his face and figure his utter prostration—a prostration quite inconsistent with any visible cause. When he had rested himself, he again started forward with a nervous intensity, shambling, shuffling, falling, stooping to replace the rudely extemporised snow-shoes of fir bark that frequently slipped from his feet, but always starting on again with the feverishness of one who doubted even the sustaining power of his will. A mile beyond the tree the cañon narrowed and turned gradually to the south, and at this point a thin curling cloud of smoke was visible that seemed to rise from some crevice in the snow. As he came nearer, the impression of recent footprints began to show; there was some displacement of the snow around a low mound from which the smoke now plainly issued. Here he stopped, or rather lay down, before an opening or cavern in the snow, and uttered a feeble shout. It was responded to still more feebly. Presently a face appeared above the opening, and a ragged figure like his own, then another, and then another, until eight human creatures, men and women, surrounded him in the snow, squatting like animals, and like animals lost to all sense of decency and shame. They were so haggard, so faded, so forlorn, so wan, - so piteous in their human aspect, or rather all that was left of a human aspect, - that they might have been wept over as they sat there; they were so brutal, so imbecile, unreasoning and grotesque in these newer animal attributes, that they might have provoked a smile. They were originally country people, mainly of that social class whose self-respect is apt to be dependent rather on their circumstances, position and surroundings, than upon any individual moral power or intellectual force. They had lost the sense of shame in the sense of equality of suffering; there was nothing within them to take the place of the material enjoyments they were losing. They were childish without the ambition or emulation of childhood; they were men and women without the dignity or simplicity of man and womanhood. All that had raised them above the level of the brute was lost in the snow. Even the characteristics of sex were gone; an old woman of sixty quarrelled, fought, and swore with the harsh utterance and ungainly gestures of a man; a young man of scorbutic temperament wept, sighed, and fainted with the hysteria of a woman. So profound was their degradation that the stranger who had thus evoked them from the earth, even in his very rags and sadness, seemed of another race. the practical Gabriel [24] Grace was no logician, and could not help thinking that if Philip had said this before, she would not have left the hut. But the masculine reader will, I trust, at once detect the irrelevance of the feminine suggestion, and observe that it did not refute Philip’s argument. She looked at him with a half frightened air. Perhaps it was the tears that dimmed her eyes, but his few words seemed to have removed him to a great distance, and for the first time a strange sense of loneliness came over her. She longed to reach her yearning [p.33] arms to him again, but with this feeling came a sense of shame that she had not felt before. [32] Captain Conroy’s Party [52] Chap. IX End of book I count Conroy as identified among the dead. Resumes agter five years with Gabriel in One Horse Gulch. He is now ‘Meanwhile this homely inciter of the unselfish virtues of One Horse Gulch had passed out into the rain and darkness.[57] Olly and Gabriel have escaped. he wanted to know everything that happened in Starvation Camp [60] Olly: Do you think Philip - ate - Grace (Olly) ][61] Grabriel is from Missouri Daguerrotype of Gracie [63] The Americans took possession of the Missions and Presidios [64] Gabriel is in possesion of the land-grant made to Dr Devarges [68] - doesn’t know of the mine Mrs Markle - brown but handsomely shaped arms 77 dam burst in the canon [?Wingham ditch]; the immense reserve strength of Gabriel came into play; [93] rescuer swept away; Gabriel and woman; coach passengers; POINSETT: Of course he could not prosecute this claim; of course he ought to prevent others from doing it. There was every probability that the grant of Devarges was a true one - and Gabriel was in possession! Had he really become Devarges’s heir, and if so, why had he not claimed the grant boldly? And where was Grace? / In this last question there was a slight tinge of sentimental recollection, but no remorse or shame. That he might in some way be of service to her, he fervently hoped. That, time having blotted out the romantic quality of their early acquaintance, there would really be something fine and loyal in so doing, he did not for a moment doubt. He would suggest a compromise to his fair client, himself seek out and confer with Grace and Gabriel, and all should be made right. His nervousness and his agitation was, he was satisfied, only the result of a conscientiousness and a delicately honourable nature, perhaps too fine and spiritual for the exigencies of his profession. Of one thing he was convinced: he really ought to carefully consider Father Felipe’s advice; he ought to put himself beyond the reach of these romantic relapses. [ALL 149] “And the sister, the real heiress, is gone - disappeared! No one knows where! All trace of her is lost. But now comes to the surface an impostor! a woman who assumes the character and name of Grace Conroy, the sister!” “One moment,” said Arthur, quietly, “how do you know that it is an impostor?” “I am Lieutenant Arthur Poinsett, formerly of the army, who, under the assumed name of Philip Ashley, brought Grace Conroy out of Starvation Camp. I am the person who afterwards abandoned her - the father of her child.” [170] She was gentle, she was kind, she seemed to love Gabriel - but Olly was often haunted by a vague instinct that Mrs. Markle would have been a better match 180 Mrs Conroy IS a gold digger. [186]: A terrible thought flashed suddenly upon Mrs. Conroy. Could Dr. Devarges have made a mistake? Might he not have been delirious or insane when he wrote of the treasure? Or had the Secretary deceived her as to its location? A swift and sickening sense that all she had gained, or was to gain, from her scheme, was the man before her - and that he did not love her as other men had - asserted itself through her trembling consciousness. Mrs. Conroy had already begun to fear that she loved this husband, and it was with a new sense of yearning and dependence that she in her turn looked deprecatingly and submissively into his face and said - / ”It was only a whim, dear - I dare say a foolish one. It’s gone now. Don’t mind it!” [186] {181} Dumphy’s bubble [244] Gabriel had become a great favourite with the men ever since they found that prosperity had not altered his simple nature [245] “G. C. - Look no more for the missing one who will never return. Look at home. Be happy. - P. A.” [245] Philip Ashley is Arthur Poinsett “He died as he had lived,” said Mrs. Conroy, passionately, ”a traitor and a hypocrite; he died following the fortunes of his paramour, an uneducated, vulgar rustic, to whom, dying, he willed a fortune - this girl - Grace Conroy. Thank God, I have the record! Hush! what’s that?” [296] “I’ve drawed up a little paper yer ez I’ll hand over to Lawyer Maxwell, makin’ over back agin all ez I once hed o’ you and all ez I ever expect to hev. For I don’t agree with that Mexican thet wot was gi’n to Grace belongs to me. I allow ez she kin settle thet herself, ef she ever comes, and ef I know thet chile, ma’am, she ain’t goin’ tech it with a two-foot pole. We’ve allus bin simple folks, ma’am - though it ain’t the squar thing to take me for a sample - and oneddicated and common, but thar ain’t a Conroy ez lived ez was ever pinted for money, or ez ever [p.304] took more outer the kompany’s wages than his grub and his clothes.” [303-04] accused of killing Victor Ramirez much about real estate “Your mining claim; not in the least,” interrupted Arthur quietly, ”I am not here to press or urge any rights that we may have. We may not even submit the grant for patent. But my client would like to know something of the present tenants, or, if you will, owners. You represent them, I think? A man and wife. The woman appears first as a spinster, assuming to be a Miss Grace Conroy, to whom an alleged transfer of an alleged grant was given. She next appears as the wife of one Gabriel Conroy, who is, I believe, an alleged brother of the alleged Miss Grace Conroy. You’ll admit, I think, it’s a pretty mixed business, and would make a pretty bad showing in court. But this adjudicature we are not yet prepared to demand. What we want to know is this - and I came to you, Dumphy, as the man most able to tell us. Is the sister or the brother real - or are they both impostors? Is there a legal marriage? Of course your legal interest is not jeopardised in any event.” [207] In court: The seventy-four gunship, Gabriel Conroy, was clearing the decks for action.[382] vigilance committee [besiege the jail where Gabriel is held; and escape] The old negro entered wtih a trembling step. And then [1876/459] catching sight of the white face on the pillow, he uttered one cry - a crey replete with the hysterical pathos of his race, and ran and dropped on his knees beside - it! And then the black and the white face were near together and both were wet with tears. Gabriel confesses to be Johnny Dumbledee [460]Gabriel confesses to be Dumbledee [huh] Gabriel’s supposed reason for choosing his name: ”Well, Gabriel Conroy was a purty name - the name of a man ez I onst knew ez died in Starvation Camp. It kinder came easy, ez a sort o’ interduckshun, don’t ye see, Jedge, toe his sister Grace, ez was my wife. I kinder reckon, between you and me, ez thet name sorter helped the courtin’ along - she bein’ a shy critter, outer her own fammerly.” Irish immigrant: The defence resumed. Michael O’Flaherty called; nativity, County Kerry, Ireland. Business, miner. On the night of the murder, while going home from work, met deceased on Conroy’s Hill, dodging in among the trees, for all the wurreld like a thafe. A few minutes later overtook Gabriel Conroy half a mile farther on, on the same road, going in same direction as witness, and walked with him to Lawyer Maxwell’s office. Cross examined: Is naturalised. Always voted the Dimmycratic ticket. Was always opposed to the Government - bad cess to it - in the ould counthry, and isn’t thet mane to go back on his principles here. Doesn’t know that a Chinaman has affirmed to the same fact of Gabriel’s alibi. Doesn’t know what an alibi is; thinks he would if he saw it. Believes a Chinaman is worse nor a nigger. Has noticed that Gabriel was left-handed. 464 Grace and Gabriel meet in court [467] not met since starvation camp in the Sierras [467] nolle prosequi [473] “Then I’ll go,” said Gabriel, rising to his feet. He made a few steps to the door and then hesitated, stopped, and turned toward Grace. As he did so his old apologetic, troubled, diffident manner returned.[473] Donna Dolores - I am Gabriel Conroy’s sister [...] He gave the paper to Arthur, who received it, but still retained a warm grasp of Gabriel’s massive hand. “And now,” added Gabriel, ”et’s gettin’ late, and I reckon et’s about the square thing ef we’d ad-journ this yer meeting to the hotel, and ez you’re goin’ away, maybe ye’d make a partin’ visit with yer wife, forgettin’ and forgivin’ like, to Mrs. Conroy and the baby - a pore little thing - that ye wouldn’t believe it, Mr. Poinsett, looks like me!” But Olly and Grace had drawn aside, and were in the midst of an animated conversation. And Grace was saying - / “So I took the stone from the fire, just as I take this” (she picked up a fragment of the crumbling chimney before her); ”it looked black and burnt just like this; and I rubbed it hard on the blanket so, and it shone, just like silver, and Dr. Devarges said” - “We are going, Grace,” interrupted her husband, ”we are going to see Gabriel’s wife.” Grace hesitated a moment, but as her husband took her arm he slightly pressed it with a certain matrimonial caution, whereupon with a quick impulsive gesture, Grace held out her hand to Olly, and the three gaily followed the bowed figure of Gabriel, as he strode through the darkening woods. [493-95]

[Ftn.1:] I fear I must task the incredulous reader’s further patience by calling attention to what may perhaps prove the most literal and thoroughly-attested fact of this otherwise fanciful chronicle. The condition and situation of the ill-famed ”Donner Party” - then an unknown, unheralded cavalcade of emigrants - starving in an unfrequented pass of the Sierras, was first made known to Captain Yount of Napa, in a dream. The Spanish records of California show that the relief party which succoured the survivors was projected upon this spiritual information. Round up: Grace is Donna Dolores; Julia Conroy is ______; Arthur Poinsett is Philip Ashley, having adopted the other name before the Conroy Party set out. The Dead is the last plate. Philip Ashley - Victor Ramariz? |

[ top ]

| TP & Plates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [ close ] | [ top ] |