Life

| 1914-2001 [Edmund Kelly]; b. 30 March, Sliabh Luachra, nr. village of Rathmore on Cork/Kerry border [east of Killarney], son of Ned Kelly and Johanna (née Cashman; delicate in childhood; left school at 14; apprentice carpenter to his father, a wheelwright; attracted to drama by fit-up production of Juno and the Paycock; studied at night classes in Killarney; schol. to Bolton St [DIT], and trainee woodcutter and later worked as a woodwork instructor in the National College of Art (Kildare St.); moved to work for a year in Listowel, Co. Kerry and participated in Listowel Players, succeeding Bryan MacMahon as director; m. Maura O’Sullivan, opposite whom he played in Synge’s Playboy, 1951; joined Radio Eireann Players with his wife (who was playing the part of Pegeen Mike when he met her), 1952; |

| discovered as a story-teller by Mícheál Ó hAodha, then Director of Drama and Variety, following an informal performance at a REP party following the production of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt by Tyrone Power; became established as the resident seanachie at RTÉ, presenting ‘The Rambling House’ programme; cast as S. B. O’Donnell in Hilton Edward’s production of Friel’s Philadephia (Gaiety 1962), his first professional stage role; transferred to Broadway, 1996 and became the Irish first Broadway hit since the war; nominated for a Tony; played An Piscín Piaclach in An Béal Bocht (Peacock July 1967); played again in Tomás Mac Anna’s revival of Philadelphia (1972); |

| also in The Playboy, Kobe, Translations, The Cherry Orchard, The Man from Clare, and Boss Grade’s Boys; played Dandy in The Field (touring to Russia); King Oedipus in Edinburgh; The Well of the Saints, dir. Patrick Mason; played Old Gob in Merchant of Venice (1984); Simon Doodles in Ulysses in Nighttown (1990); Brother Duffy in Silver Dollar Boys, and Pozzo in Waiting for Godot with Peter O’Toole and Donal McCann; Pats Babock in Sive, a two-hander adapted for him and his wife from The Tailor and Ansty (1968), and Stone Mad, dir. Sean McCarthy and adapted by Fergus Linehan from Seamus Murphy’s book; his last role was Father Willow in Marina Carr’s The Bog of Cats (1998); |

| wrote Scéal Scéalaí with Tomas Mac Anna, an Irish Theatre Story series; also authored his own storytelling shows, In My Father’s Time, Bless Me Father, The Rub of the Relic, The Story Goes …, English That for Me (1980; NY TADA 1989), A Rogue of Low Degree, and Your Humble Servant; toured with Field Day production of Three Sisters (1981); ITC’s production of On Baile’s Strand and Sharon’s Grave; appeared in Sebastian Barry’s Boss Grady’s Boys (1989); played Philadelphia at the London Lyric, 1992, and Colleen Bawn at Manchester Royal Exchange; recorded Legends of Ireland with Rosaleen Linehan (1985), distrib. to 3,000 schools; awards incl. Kerry Person of the Year, 1984, Harvey Special Services Award, 1986; |

| National Entertainment Hall of Fame award, 1991; hon. doct. NUI, and Gradam Amharclann na Mainistreach [Abbey premier award], 1991; issued an autobiography, The Apprentice (Marino 1995), of which instalments appeared in Sunday Independent (17 & 24 Dec. 1995); d. 24 Oct. 2001; survived by Maura, and their children Eoin, Brian and Sinead; brs. Johnny Laurence and sistas Hannah and Bridie. |

|

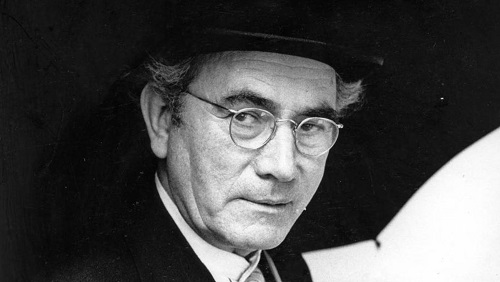

| Irish Times photo accomp. Fintan O’Toole, “Culture Shock [...]” (infra) |

|

| Reprints |

|

| [Check bio-dates and chk. for author of the same name.] |

[ top ]

Commentary

John Devitt, Books in Brief [notices], in Irish Literary Supplement; A Review of Irish Books (March 1996) remarks that The Apprentice (Mercier 1995) remarks that versions of the stories of Frank O’Connor’s The Guests of the Nation, and Synge’s Shadow of the Glen can be found here.

Anna Cooke has warm praise for Ireland’s Master Stortyteller (1998) in Books Ireland, Oct. 1999 (p.278), quoting: ‘The other two girls had got married, he had no trouble getting rid of ‘’em, but there was no demand for nell on account of she couldn’t talk.’

The Irish Times (Obituary): Eamon Kelly, d. 24 Oct. 2001; b.1914, nr. village of Rathmore on Cork/Kerry border, son of Ned Kelly and Johanna (née Cashman; delicate in childhood; left school at 14; apprentice carpenter to his father; night classes in Killarney; schol. to Bolton St [DIT]; acted with Listowel Players, succeeding Bryan MacMahon as director; m. Maura O’Sullivan, 1951; joined Radio Eireann Players with his wife (who was playing the part of Pegeen Mike when he met her), 1952; discovered as a story-teller by Mícheál Ó hAodha, then Director of Drama and Variety, following an informal performance at a REP party following the production of Peer Gynt by Tyrone Power; cast as S. B. O’Donnell in Hilton Edward’s production of Friel’s Philadephia (Gaiety 1962), his first professional stage role; transferred to Broadway, 1996, and nominated for a Tony; played An Piscín Piaclach in An Béal Bocht (Peacock July 1967); played again in Tomás Mac Anna’s revival of Philadelphia (1972); also in The Playboy, Kobe, Translations, The Cherry Orchard, The Man from Clare, and Boss Grade’s Boys; played Dandy in The Field (touring to Russia); King Oedipus in Edinburgh; The Well of the Saints, dir. Patrick Mason, Old Vice; played Old Gob in Merchant of Venice (1984); Simon Doodles in Ulysses in Nighttown (1990); Brother Duffy in Silver Dollar Boys, and Pozzo in Waiting for Godot with Peter O’Toole and Donal McCann; Pats Babock in Sive, a two-hander adapted for him and his wife from The Tailor and Ansty (1968), and Stone Mad from Murphy’s book; his last role was Father Willow in Marina Carr’s The Bog of Cats (1998); wrote Scéal Scéalaí with Tomas Mac Anna, an Irish Theatre Story series; also authored his own storytelling shows, In My Father’s Time, Bless Me Father, The Rub of the Relic, The Story Goes …, English That for Me (1980; NY TADA 1989), A Rogue of Low Degree, and Your Humble Servant; toured with Field Day production of Three Sisters (1981); ITC’s production of On Baile’s Strand and Sharon’s Grave; played Philadelphia at the Lyric (London), 1992, and Colleen Bawn (Royal Exchange, Manchester); recorded Legends of Ireland with Rosaleen Linehan (1985), distrib. to 3,000 schools; awards incl. Kerry Person of the Year, 1984, Harvey Special Services Award, 1986; National Entertainment Hall of Fame award, 1991; hon. doct. NUI, and Gradam Amharclann na Mainistreach [Abbey premier award], 1991; survived by Maura, and their children Eoin, Brian and Sinead; brs. Johnny Laurence and sistas Hannah and Bridie. (The Irish Times [Weekend], 27 Oct., 2001, p.16.)

[ top ]

| Fintan O’Toole, ‘Culture Shock: Dirty minds and no holy families in Eamon Kelly’s Kerry’, in The Irish Times (20 Sept. 2014): We might think of him as a seanchaí who had come down from a mountain and been transplanted to Dublin with his stories intact, but he was nothing of the kind [sub-heading]. |

There’s a wonderful letter among Eamon Kelly’s papers in the National Library of Ireland, written to the great actor in 1960 by Pat Brosnan, a farmer in Scartaglen, Co Kerry. Brosnan describes himself out in the haggard, making up a story for Kelly to use on his radio programme. As he’s thinking through the story, he is, as he puts it charmingly, "talking out laughing". His wife watches through the kitchen window: “ ‘I had my eye on you, you should see a doctor. Or was it the fairies you were talking to? You have the heart turned on me I declare.’ So I answered quite cool, ‘I am glad you have your eye on me all the time – it reminds me of our young days when you would be throwing the glad eye across the dance floor at me, and I have my perfect senses all the time and your heart will be set right again when I tell you I was only making up a story for Kelly.’ ” This is lovely on a number of levels. Kelly, who was born a century ago this month and died in 2001, was thought of during his career as an authentic survivor of an old culture, a traditional seanchaí who had come down from a mountain in Kerry and been transplanted to Dublin with his stories intact. He was nothing of the kind, of course: he was one of the most sophisticated performers of the modern Irish theatre. But then “authentic” storytellers were pretty sophisticated, too: Brosnan in this letter is telling a story about how he made up a story, precisely so that it should be “collected” and broadcast. And within this story there is something that is never far from Kelly’s own narratives: the sexual tension of the wife’s gaze on her husband, both now and in their remembered youth. In some respects Eamon Kelly was too good for his own good. He created a persona so apparently natural, so real, that he barely seemed to be performing at all, even though every movement, gesture and nuance of intonation was crafted with infinite care. He stood on stage in vaguely mid-20th-century costume, usually in a re-created rural kitchen and conjured the past – a period that ran all the way from the dawn of humanity to what he slyly called "my father’s time". “Theatre of the hearthstone” He succeeded wonderfully – so well that it was all too easy to forget that he was very much within his own time, that he was shaping, inventing and indeed inspiring stories rather than merely collecting them. He was doing something much more important than preserving an old, pre-electric Irish world. He was mediating between that world and an emerging modern Ireland. And he was also subtly altering the image of that Irish past, subverting the whole notion of an old Ireland that was pure and holy. Kelly, the son of country carpenter and himself in his early manhood a travelling woodwork teacher, knew Kerry intimately and came out of its rural storytelling culture. But he knew it too well to reproduce a cliched version of what it was supposed to be like. Was it, for example, the priest-ridden place of legend? Kelly’s stories give us a society in which priests loom very large as figures of intimate authority. But they also show an attitude to that authority that is quietly sceptical, sometimes to the point of mockery. He relates the story of the two Jesuits who heel up on a farmer’s house at dinner time. The wife kills two young cocks to cook for the priests while giving her husband a scrap of cold bacon. Later the priests spot the farmer’s old rooster crowing in the yard and remark that it seems proud. “No bloody wonder,” says the disgruntled farmer, “and he having two sons in the Jesuits.” Where does this story come from? Not from a farmer, of course, but from Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds. Except that, in the original, the victim of the Jesuits’ greed is himself a parish priest, blunting the anti-clerical sting. Kelly uses the story to point up a tension between obedience to the clergy and resentment against them. A saying he quotes in another story is "be civil and strange with the clergy" – advice from a common wisdom more complex than received images of a cowed Catholic Ireland. Marriage and sex |

| —Available at The Irrish Times (20 Sept. 2014) - online; accessed 31.09.2023. |

[ top ]