| b. Connorville, Co. Cork; son of namesake, a Protestant landowner of Connerville [later Carrigmore], nr. Dunmanway, Co. Cork - prob. descended from Cromwellian soldier called Conner who received land around Bandon; ed. TCD but did not graduated; joined the Irish bar, 1783; m. Louisa Anna [née Strachan], dg. of Army colonel, with whom a son Roderick who settled in Van Diemen’s Land; also a dg. Louisa; came into Connerville when his elder br. left the country, pursued by law; hunted Whiteboys as a captain in the yeomanry but also joined the United Irishmen and later espoused the democratic principles of his br. Arthur O’Connor [q.v.]; second marriage with Wilhelmina [née Bowen], with whom sons Feargus O’Connor [q.v.] and three others of whom Francis Burdett O’Connor, the youngest, became an officer in the Simon Bolivar’s army; |

| known to associate with United Irishmen and probably owner-editor of the Harp of Erin, he was arrested on information from his br. Robert, a neighouring land-owner at Fortrobert [estate], and imprisoned during winter of 1797-98; moved to London on release and there re-arrested, publishing To the People of Great Britain and Ireland (1799), a pamphlet on his supposed persecution by the oligarchy and the Anglo-Irish; imprisoned in Fort George along with other United Irish lealders incl. his uncle Arthur, 1799 - but released early in 1801; received executorship of Arthur’s estate and swindled him for its value; acquired the lease on Dangan Castle at Trim, Co. Meath, property of the Wellesley family, 1803; claimed insurance premium of £5,000 when it was destroyed by fire, 1809; rebuilt the house and supposedly ran a gang of highwaymen out of it; arrested for ’inciting robbery of the mail coach Cappagh Hill [Galway], 2 Oct. 1812; tried and acquitted to public jubilation, 1817 [see note]; his subsequent perjury charge against Daniel Waring, a presumed accomplice, resulted in Waring’s leaving the country; |

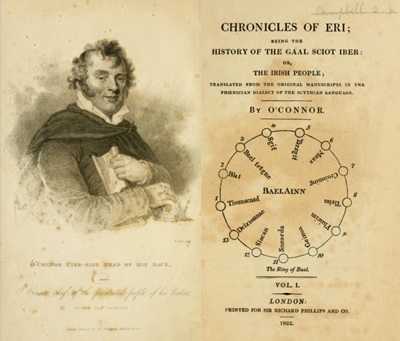

| issued The Eleventh Conspiracy of the Oligarchy of England and their Anglo-Irish agents (1817), a pamphlet; claims to have written a history of ancient Ireland during imprisonment in 1798-99 and afterwards in Fort George, but lost it through capture and misadventure; concluded it on the ‘fourth attempt’ as The Chronicles of Eri (2 vols. in 1, 1822), in which he proposed the ְidentity of the dialects of Phoenicia and Eri’ [i.e., Irish], arguing further that that Ireland had been ruined by the arrival of Christianity just as the Phoenician culture of Carthage and Tyre were destroyed by the ‘barbarous Roman[s]’; the work contains prefatory material of 300 pages extent [i-cccxlvii), and 91 pages of so-called translation under the title of “The Writings of Eolas”, allegedly from Phoenician - a book considered ‘is mainly, if not entirely, the fruit of O’Connor’s imagination’ (DNB) but laden with philological lore of the period and much nationalist historiography recognizably in the vein of historiography then and thereafter; publ. by Sir Richard Phillips & Co., London, with a preface dated ‘Paris 1821’); |

| issued, with Michael J. Whitty, Letters to his Majesty, King George the Fourth, by Captain Rock (London: B. Steill 1828) - taking up Thomas Moore’s facetious suggestion about his ownership of the name [see infra] and addressing the English monarch as ‘cousin’ and ‘brother’ and berating the oligarchy for the plight of Ireland; suffered decline in mental capacity in his later years [possibly a false interpretation of his conduct]; tried for the seduction of one Margaret Dawes in 1828; retired to Knockenmore Cottage nr. Kilrea, Co. Cork, cohabiting there with a peasant woman whom he asserted to be a descended from Gaelic royalty; professed himself an agnostic to the parish priest, Fr. Croly, who attended him in on his deathbed; bur. 27 Jan., Kilcrea, and bur. at . at Kilrea Abbey. ODNB DIB DIH |

[The earlier RICORSO notice on Roger O'Connor has been emended in the light of the outstanding article by C. J. Woods in Dictionary of Irish Biography (2009) which casts much light on the relationship between and his father (Roger), sons (Roger and Arthur), and son (Feargus). It also reflects a re-examination of the Chronicles of Eri, now available at Internet Archive. Numerous details in it are at variance with received biographical account in the reference works cited above (ODNB, DIB (Boylan), and DIH). In some of those the burning of Dangan Castle is more expressly cited as arson while O’Connor is said to have robbed the Galway coach in order to capture love-letters incriminating his friend Sir Francis Burdett - represented by Woods as a character witness only. Burdett is the dedicatee of Chronicles of Eri and the recipient of a dedicatory letter and later under the heading “Burdett arrives in Ireland, 1817”. The bibliographical focus of the present work prevents deeper examination of the record at this time. 18.06.2024.]

Dangan Castle in c.1840

[ top ]

Works| Historical |

|

| Pamphlets |

|

|

|

Bibliographical details

| Chronicles of Eri: History of the Gaal Sciot Iber or the Irish People, translated from the Original Manuscripts in the Phoenician dialect of the Scythian Language, by O’Connor (London: Sir Richard Phillips and Co. 1822), 2 vols. (1822) - Vol. 1, xvii, cccxlii, [Postcript], 1-91pp. [The Writings of Eolas], [5 blanks]. Frontis. shows ‘O’Connor, Cier-Rige Head of his Race, and O’Connor, chief of the prostrated people of his Nation, soumis pas vaincus [engrav. port, London: printed for Sir Richard Phillips & Co.]; title page shows device with 13 radiated points, ‘The Ring of Baal’, marked anti-clockwise 1-13 Tionnscnad, Blat, Bal tetgne, Sgit, Tarsgit, Meas, Cruinnige, Tirim, Fluicim, Geimia, Sneachda, Siocan, Deirionnae; also a fold-out map of ‘Western Asia, marked in Latin [Mare Internum, etc.]; a map of Spain; and a map of Britain, with details for S. Wales, Cornwall, and N. England [viz., Northumbria]. [by J.M’Gowan, Great Windmill Street.] | ||

| CONTENTS: | ||

Letter of dedication to Sir Francis Burdett of Foremark, Baronet (iii-vi); Preface ([xvii]-xii - see extract]); Contents ([xiii]-xiv]); Contents of the Demonstration ([xv]); Directions for placing the Engravings ([xvi]); Demonstration of the Original Seat, Nations, and Tribes of the Scythian Race - Pts. I-IV [i]-ccclxii [Conclusion, cccxlviif]; Postscriptum(i-ii); The Writings of Eolas (pp.1-99). |

||

| A demonstration, pp.i-cccxii; The Writings of Eolus, pp.1-99 [conclusion of chronicle of Gaelag]. Demonstration contains sects. 1] a demonstration of the original seat, nations, and tribes of the Scythian race. 2] from the eariest accounts of the existence of this earth to the founding of Babel 3] from the dismemberment of the anc. Scyhtian empire, and the building of Bab-el by the Assyrians, in 246, to the expulsion of the shepherd chiefs from Egypt, and their arrival in Pelesgia and Ceropeia, in about 1100 before Christ. 4] Of all the Scythian tribes that emigrated to the Isles of the Gentiles, south of the Ister, from the Euxine, East to the Rhoetian Alps, and Panonia West to the extremity of Greece South, from the year 2170 to the birth of Christ. 5] Of the Scythian tribes that colonised th districts of Europe, from the western extremity of Italy, and the Rhoetian Alps, to the German Ocean, between the rivers Danube, and Rhin, north and the Garonne south. 6] Of the Goths 7] Of the Scythian sidonians in Spain 8] Of the Scythian tribes in the Isle of Britain 10] Of all the nations of Europe, antecedently to the invasion of the Scythians. 11] Of the Manners, Customs, Original Institutions, and Religion of the Scythian race 12] Of the language of the Scythian Race. Conclusion, cccxlix. Begins with Dedicatory letter to Sir Francis Burdett, speaks of putting evidence of ‘the last conspiracy against my life and honour, by agents of an oligarchy’ and the revolution; ‘the iron-hand of despotism; seeks a ‘fostering hand’ for his children; also speaks of ‘my gallant boy’ into whose hands Burdett placed his first weapon with instructions to use it against ‘tyranny and oppression’; ‘your never-failing advocacy and vindication of the Irish people, has endeared you to all our hearts.’ [v] |  |

|

Preface: fourth effort … to present to the world a faithful history of my country … immured in prison … 1798 and 1799 charged by the oligarchy of English with the foul crime of treason, because I would not disgrace my name by the acceptance of an earldom and a pension, to be paid by the people whom I was courted to desert, and because I resisted every art to induce me to become a traitor to my beloved Eri … Fort George, Scotland … again writing’. He gives an account of the successive destructions of the manuscript. He reports that a third version perished with his belongings in the fire at the castle of Dangan in 1809. ‘[of] liberty we wild Irish have none to lose’ [ix] Burdett arrives in Ireland, 1817. ‘This history is a literal translation into the English tongue (from the Phoenician dialect of the Scythian language) of the ancient manuscripts which have, fortunately for the world, been preserved through so many ages, chances and vicissitudes.’ [ix.] ‘… I do not presume to affirm that the very skins, whether of sheep or of goats, are of a date so old as the events recorded; but this I will assert, that they must be faithful transcripts from the most ancient records; it not being within the range of possibility, either from their style, language, or contents, that they could have been forged’ [ix]

On p.vi of his first chapter, O’Connor introduces his narrator, Eolus, who lived 50 years later than Moses, and was chief of the Gaal or Sciot of Iber within Gaelag, between 1368 and 1335 b.c. There is much reliance on Herodotus, Strabo, Thucydides, Polybius, etc. [Compares modern day writers to ‘the manner of Anglo Irish juries, who submit their oath to the arbitrament of chance (c) lxxi; a note relates that in a case of damages, the value is fixed between the highest and lowest sum named by the Anglo-Irish jurymen on their oaths]. Throughout, O’Connor makes extensive use of analogies and homologies between Irish [i.e., Eri, dialect of the Scythians] and Greek and Roman names. For instance, he glosses Greek Ogyges, ‘supposed to be an individual, a king of Attica, in 1766, before Christ: ‘Og-eag-eis, ‘the diminution of Og’s multitude’, the explanation heretofore given on this head, has, it is to be hoped, confuted all the fabulous relations, and demonstrated the fact; it is to be farther remarked, that the nae of Og-eag-ia hath been applied to Eri, from tradition, and frgments of old poems, at a time, and by men, who had no idea of founding s system thereon, but merely because th fact of the Gaal of Sciot having emigrated from Ib-er, which was one of the nations of Magh-Og, has never been lost sight of, and you will find by the chronicles of the Iberian races in Spain, they called themselves Og-eag-eis, and Noe-maid-eis.’ [clxxiii]. The name Bosphoros is glossed as ‘Cos-foras’, compound of Cos, or the foot, and Foras, a wa through or over the water [idem]; Maes-ia, glossed ‘Meas-iath, the land of acorns’ [clxxx]. On p.clxxxvii following he lists ‘a variety of words in th dialectics of Greece, Italy, and Eri, of the same signification in all, wherefrom you will have an opportunity of witnessing that the dialects of Greece and Eri bear a nearer resemblance to each other … &c’. Examples are Aggelos, Giola; Akrasia, Craos [gluttony]; airesis, airioch-seis [election]; amnes[t]ia, main-aide [out of mind]; eros, er [hero]; kalon, glan [neat]; kiste, ciste [chest]; lauros, go leor [abundant]; lithos, liath [stone]; phero, bear-im [I carry]; pornos, foirneadh [violent passion or inclination, i.e., adultery - here O’Connor cites Matt. 5.28]; Selene, Sul-lu-aine-e, ‘It is the light of the lesser orb or ring’; Phos, fos [light]. Vol 1 contains the Chronicle of Gaelag, being prior to the arrival in Ireland. Eolus is made to count years of reigns as ‘rings’. Vol. 2 contains the Chronicles of Eri, Part II; commencing with ‘the annals of Eri’. A Frontispiece folding map shows Ireland with selection of ancient names inc. provinces. ‘What if this land, standing alone, an island, be called ERI for times to come? [7] … this place is too large for one chief’ [8] The final chapter of the narrative of Eolus takes events up to ‘the reign of Factna, the son of Cas, the son of Ruidhruide Mor king in Ulladh, Ardri, a space of one score and three years, from 30 to the year 7 before Christ.’ After a chronology extending across the full world-history involved, O’Connor ends: ‘And now I take my leave for the present, wishing health and happiness to all the good people of the earth, and speedy amendmnt to the vicious; and if my health will prmit (I shall certainly carry the victory over my adverse circumstances), I hope early in the year that is to ensue, to present the world with a continuation of the history of my adored Eri.’ [End] |

||

| [ See Preface in Quotations - infra. ] | ||

|

||

[ top ]

Criticism

T. Finnerty, The Irish Patriot: The Trial of Roger O’Connor, Irish Patriot and Friend of Sir F. Burdett, on a charge of Robbing the Galway Mail Coach, Dec. 1812 (London: Fairburn c.1820), 48pp.; R. R. Madden, ‘Memoir of Roger O’Connor, Esq.,’ in The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times [... &c.], 2 vols. (Dublin 1858), Vol. 2, pp.590-612; see also chapter-essay in Robert Tracy, The Unappeasable Host: Studies in Irish Identities (UCD Press 1998).

|

[ top ]

| Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representation of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century (Cork UP/Field Day 1996)´- extract. |

|

|

|

| (Leerssen, op. cit., pp.199, pp.82-85.) |

The engagement between Moore, Rock and O’Connor did not end with the Memoirs. Captain Rock did not cease his literary career when Moore was done with him: O’Connor grasped the momentum of Moore’s book and adopted the persona of Captain Rock explicitly for his own when he brought out, in 1828, the Letters to his majesty, King George the Fourth, by Captain Rock. Moore’s satirical persona is kidnapped, or emancipated, from its author, and the ex-United Irishman O’Connor/Rock delivers a magnificent piece of effrontery in his own voice. He continues the conceit of Memoirs of Captain Rock by opening the book with an Introductory Letter from New York, 1 June 1826 (where we may suppose Moore’s fictional persona to have arrived following his emigratory farewell at the close of the Memoirs'). That introductory letter is addressed, in sham Irish, Do Uia Morda (read: do Ua Mórdha: To Moore), and pays Moore a back-handed compliment for having presented the Captain’s memoirs to the world in such a stylish manner.* (It is important to remember that Memoirs of Captain Rock came out anonymously and that Moore’s authorship was at best a matter of public conjecture.)

Nor is that all. O’Connor’s Captain Rock has footnotes added to his letters to George IV (who, in noble fashion, is addressed affably as ‘Sir, My Cousin’ - one king to another); and these footnotes are all signed with the initials ‘U.M.’ Are we to construe that, following the introductory letter, as ‘Ua Mórdha’? Even to entertain the mere suspicion is to fall victim to O’Connor’s mystifications. In these anonymous and pseudonymous books, using half-mythical personae linked vaguely to real-life persons, who is to say what identity is authentic or false, assumed or imputed for purposes of legal anonymity or hoaxing trickery? Even O’Connor’s authorship of the Letters to George IV is something we must infer from textually circumstantial evidence. [87]

|

[ top ]

Quotations

| Chronicles of Eri: History of the Gaal Sciot Iber or the Irish People, [...] (1822) |

| PREFACE. |

|

THIS IS the fourth effort which I have made, to present to the world a faithful history of my country. Whilst I was immured in a prison in Dublin, during parts of the years 1798 and 1799, charged by the oligarchy of England with the foul crime of treason, because I would not disgrace my name by the acceptance of an earldom and a pension, to be paid by the people whom I was courted to desert, and because I resisted their every art to induce me to become a traitor to my beloved Eri, I employed my time in writing a history of that ill-fated land, which I had brought down to a very late period, when an armed force of Buckinghamshire militia men entered my prison, and all the result of my labours, with such ancient manuscripts as I had then by me, were outrageously taken away, and have never since been recovered.

|

|

| Chronicle of Eri is available at Internet Archive - online. 19.06.2024 |

| Demonstration [extract] |

| [...; ccvli] |

I now come to present you with a specimen that affords proof incontrovertible of the identity of the Phœnician and Iberian language, as written at this day in Ireland, with the circumstances connected with which proof, it will be necessary to give you some previous information. |

| I |

Nith al o nim, ua lonuth sicorathissi ma com syth |

| II |

|

| [ccxlii] |

| III |

|

| IV |

|

| V |

|

| This address to the unknown deity of the country being concluded, Hanno having had information that his daughters were in the temple of Venus, hastes thither, and utters the following sentiment on the recollection of the attributes of this goddess. |

|

| (a) Tetgne is pronounce tinni (p.ccvliii; section end.) |

| And now having met with Giddenenie the nurse of his daughters, and reproached her, she replies, |

|

| There is no necessity to offer any remark on the above, such as that ; Plautus was a Roman, and must be supposed to have introduced some letters of the characters of his own nation, not known in Carthage, as the h and 3*, (and these are the only Roman letters in these lines) nor whether he copied in Phoenician or Roman figures, nor yet whether many, few, or [ccliii; ...] |

|

[...] |

| Ensuing sections: on ‘Of the Language of the Cimmerii, Cimbri, or Germanni’ (X); Of the Language of the Celtæ (XI); ‘Arrived in Britain, I now come to speak of the various nations thereof ...’ (XII); . |

|

‘[...] In fine Lhuyd is perfectly correct in saying, that all the most ancient names of places in Britain are in the Irish language, but is erroneous in fancying it to be Guydhelian, of which word I can but guess at the meaning, and suppose it to be a kind of English translation of the bard’s monstrous distortion of Gaal, of which they made Gaoidhiol, for the sake of their rhymes, if this be the word, the misconception of Lhuyd is complete in every case, his Guydhelian being the common or ordinary name of the Iberian and Scottish dialect of the Scythian tongue, signifying neither more or less than the language of the Gaal, that is, the Gael of Sciot of Iber, heretofore fully explained.’ (cccxliii [343]). |

[ top ]

| The Chronicles of Eri (London 1822) - Demonstration [extract from Conclusion]. |

| [...] |

The Gaal Sciot Ib-eir having established themselves in three quarters of Eri, [t]heir chronicles will inform you, that the genuine feodal system was in perfect operation. [cccli] Government executed by a single chief elected, These Chronicles will instruct you, that at the time of the arrival of our forefathers from Gaelag in this island, they found, nor had they heard of, but two races of mankind, one the aborigines, whom they called Ce-gail or Fir-gneat, and preceding invaders, who called themselves Danan, and that Partholanus, Nemidius, African giants and pirates, and Damnonian necromancers, are children of fable, fictions of the fancy of the bards. They shew that the Sidonians, so far from having any intercourse with this island, as some superficial schemers have fancied, never approached the shores save once, and then were not suffered to come to land ; And that the Gaal Sciot Ib-eir abided altogether within Eri, for seven hundred years, without communication with any other people, till a tribe of Basternae, of the specific denomination of Peucini,. according to the Romans, by us called Gaal of Feotar, arrived in this island, from whence they shaped their course to Ailb-binn, between whom and us, these records prove the connexion. These Chronicles, and this Demonstration, will be the [ccclii] means of enabling all who are endued with understanding, to comprehend the reason of Cyrus, the Elamite or Persian Scythian, (whose mother was Mandane, the daughter of Astyages, the Median Assyrian) being called a Mule, to appreciate truly the portion of Hebrew story ascribed to Daniel, his capability to fix the termination even to one night, of the Assyrian empire in Babylon, his treason to Bels-assur, the Assyrian, his adherence to Cyrus the Scythian, the tale of Daniel and the Lions, the favor of that prince towards him, and the decree authorizing the Hebrew Scythians captivated by the Gentile Assyrians to return to their own land, and rebuild their Temple. This will explain the cause of the course pursued by Og-Eisceann, on his invasion of western Asia, why he fastened on Media, did not spare the children of Israel, and meditated a descent on Egypt, clearly demonstrative of the difference of origin of the Scythians, Assyrians, and Egyptians, and of the disrespect of the genuine Scythians for the Hebrew branch of that vast family, in consequence of their separation from the children of their race. These Chronicles will point out to you the perfect similarity in the mode of public assemblies in Greece and Italy, and in Eri, the former at the Prytaneium Demoi, the latter at the Briteini Duine, the fire hill close to Asti, as well as in those multitudinous customs peculiar to the Scythian race, mentioned in the Demonstration. |

—See full copy of “Conclusion” [to of “Demonstation”], in The Chronicles of Eri (1822), Vol. I - as attached. |

References

Dictionary of National Biography [ODNB]: English bar 1784 [sic]; imprisoned with his brother Arthur; involved in insurance crimes; Chronicles of Eri, mainly imaginative; other details as above [referring ro prior verion as follows: ‘1762-1834; b. Connorville, Co. Cork; f. of Feargus O’Connor; ed. TCD; English bar, 1783; hunted Whiteboys in yeomanry; joined United Irishman; arrested at instance of br. Robert, acquitted; imprisoned in Fort George, 1799-1803; adopted acronym ROCK (for ‘Roger O’Connor, King’); relating to destruction of Dangan Castle, Trim, Co. Meath, by fire, for insurance premium of £5,000; eloped with married woman; arrested for robbing the Galway coach in order to capture love-letters incriminating his friend Sir Francis Burdett, 1817; tried and acquitted; father of Feargus O’Connor; issued Chronicles of Eri (2 vols., 1822), alleged trans. from Phoenician; d. 27 Jan., Kilcrea, Co. Cork.’ [PGIL-EIRData/Ricorso 1996-2014.)

Dictionary of Irish Biography (RIA 2009) - “Roger O’Connor” by C. J. Wills, incls. the following details and remarks: ‘When going into exile (1802) Arthur O’Connor gave Roger (who was allowed to return to Ireland) power of attorney to manage his Irish property (worth £1,200 p.a.), from which he expected income to be remitted; Roger, however, sold part of it and kept the proceeds (about £10,000); Arthur replaced Roger with their brother, Daniel, took protracted legal action against Roger, and many years later obtained some redress. After his release from Fort George and return to Ireland, Roger O’Connor purchased (1803) the lease of Dangan Castle, Co. Meath, the property of Richard Colley Wellesley, 2nd earl of Mornington, brother of the future duke of Wellington; he intended it to be a house fit for the reception of Bonaparte should he invade Ireland. In 1809, not long after it was heavily insured, the castle was destroyed by fire. It was rebuilt, and appears to have been used by O’Connor as a base from which to lead a gang of bandits to rob mail-coaches and commit other thefts, storing the booty in a vault or dividing it between his accomplices. This was what William John Fitzpatrick was told many years later by “a very truthful coachman”, a native of Dangan. On 5 August 1817, O’Connor was tried at the Meath assizes at Trim on a charge of being the principal agent in the robbery of the Galway mail-coach at Cappagh Hill, Co. Kildare, on 2 October 1812. The English radical Sir Francis Burdett came from England to attest to O’Connor’s good character; O’Connor was acquitted amid great acclamation, almost immediately brought out a pamphlet denouncing the government, The eleventh conspiracy of the oligarchy of England and their Anglo-Irish agents (1817), and began criminal proceedings for perjury against one of the witnesses against him, Daniel Waring, a former accomplice. Waring was acquitted but had to leave Ireland secretly. / It would appear that after 1817 O’Connor’s mental health was in decline. His next publication was Chronicles of Eri; being the history of the Gaal Sciot Iber, or the Irish people (2 vols, 1822) [...].’

Bibl. cites [inter alia] R. R. Madden, The United Irishmen, 2nd edn., Vol. II (1858), pp.330-31, 590-612, Vol. IV (1860), pp.104, 114, 119; W. J. Fitzpatrick, Ireland before the Union (1867), pp.195-8, 202-8; W. J. O’N. Daunt, Ireland and her Agitators (1867), pp.102-4; and Frank MacDermot, “Arthur O’Connor”, Irish Historical Studies, XV: 57 (March 1966), pp.49, 64, 66. (Dict. of Ir. Biog. - available online; accessed 19.06.2024.)

Hyland Catalogue No. 219 (Oct. 1995) lists An Address to the People of Ireland Shewing them Why they ought to Submit to an Union (Dublin 1799), 16pp.

Belfast Public Library holds to the People of Great Britain and Ireland (1799); View of the System of Anglo-Irish Jurisprudence and the effects of trial by Jury [in cases of faction] (1811); Chronicles of Eri. History of the Gaal Sciot Iber or the Irish People, translated from the original manuscripts, 2 vols. in 1 (1822). defendant, Margaret Dawes widow plaintiff, Roger O’Connor, attorney defendant; trial for the seduction of Margaret Dawes (1828).

National Library of Scotland holds Chronicles of Eri; being the history of the Gael Sciot Iber: or, the Irish people; translated from the original manuscripts in the Phoenicians dialectic of the Scythian language. Vol. I (London: Sir Richard Phillips & Co. 1822).

Notes

Dangan Castle, Co. Meath, was the birthplace of Richard Colley Wellesley, 2nd Earl of Mornington and Marquess (1760-1842), Lord Lieutenant in 1821-28, and 1833-34 (See Doherty and Hickey, A Chronology of Irish History since 1500, Gill & Macmillan 1989). See also Hubert Butler, ‘Dangan Revisited’, in Grandmother and Wolfe Tone, 1990): ‘[…] the house passed to a Mr Roger O’Connor, who cut down all the trees he could sell and skinned the rooms of every saleable fitting. Finally, after it had been well insured, the house burst into flames. No great effort was made to quench them.’ Further, Dangan was visited by Mrs Delany. The house belong to a Mr Wesley, who acquired a peerage, and a boy, who was to be Mrs Delany’s godson and the father in turn of the Duke of Wellington. ‘It is possible that he [Wellesley] disliked the middle-class associations which cam to the family name through his kinsman John Wesley.’ (p.105.)

Etymology: O’Connor derived Palatinus from Gaelic for ‘the high place of the fire of the multitude’ and Italia from Iataille, ‘the most beautiful country’, both supposed words in Gaelic. See Celtica, 1967; catalogue of Celtic works in National Library of Scotland.

[ top ]