Life

| 1831-1915 [usu. called “O’Donovan Rossa”; has been called “the Irish Samuel Adams”; also “Jerry Dynamite, and Dynamite O’Donovan Rossa”]; b. Reenascreena [Roscarbery], Co. Cork; son of Denis, a tenant farmer, and Nellie [née O’Driscoll]; Irish speaker from childhood; he acted as relief worker during Great Famine; his father Denis succombed to the Famine; family possessions put up for auction by his widow Nellie, who emigrated to America with her children in 1848 - excepting Jeremiah, who ran a grocery business in Skibbereen; fnd. Phoenix National and Literary Societies, incorp. membership of a similar society formed at Skibbereen in 1856; becoming a Fenian organiser on the invitation of James Stephens, 1858; betrayed by a priest-informer, resulting in the Phoenix Conspiracy Trial of 1859, at which he was acquitted; |

| emigrated to America and returned to Ireland, 1863; served as business mgr. of the Irish People, 1863-1865; organised moon-light pike and rifle drill for IRB members in West Cork; betrayed to the RIC by paid informer Daniel O’Sullivan Goulda, December 1858; held in Cork Jail until July 1859 when he was released on assurances of good behaviour; moved to New York, 1863; found employment as an editor for the New York Herald; worked with John O’Mahony to build the Fenian Brotherhood; became publisher of the Gaelic American; return shortly to Ireland to serve as business manager of the Irish People [IRB organ]; paper suppressed and O’Donovan re-arrested 1865, on evidence of Pierce Nagle, an informer, while leaving the shop of George Hopper, drapier (being James Stephens’s br.-in-law), Crane Lane, Dame St.; sentenced penal servitude for life (20 years), following a dock-speech of eight hours assailing Judge William Keogh and the ‘dirty law’; |

| held in three prisons - Portland, Chatham and Pentonville - and subjected to particular cruelty at Chatham Jail - including 35 days in handcuffs behind his back and eating from a bowl on the floor; was thence made the object of a popular campaign spearheaded by his wife Mary Jane [née Irwin, 1845-1916 - see note]; remained in jail during the Fenian Rebellion, 1867; elected MP for Co. Tipperary, while still held in prison, Nov. 1869, defeating the Liberal Catholic Heron by 1,131 to 1,028 votes; election annulled by Government [ineligible felon]; released on conditional pardon, Jan. 1871 following a campaign by the Amnesty Association and questions in the House raised by George Henry Moore, being amnestied with John Devoy, Charles O’Connell, and others of the ‘Cuba Five’; emig. to the US on terms of banishment, receiving a welcome from House of Representatives; met t President Ulysses S, Grant in 1871 and railed against Tammany Hall corruption, competing for office against Boss Tweed as a US Republican; |

| worked as a hotel manager, and contrib. to The Irishman; elected Fenian Head Centre, 1877, opposing the moderatism of John Devoy, and founded the ‘bombing school’ in Brooklyn; broke with Clann na Gael, 1880; was shot and wounded in his New York office in attack by Yseult Dudley, an Englishwoman enraged by his founding role in the Skirmishing Fund of Clan na Gael - with bombings in England in view, 1887; betrayal by otorious ‘Red’ Jim McDermott led to the arrest of Tom Clarke and others; fnd. and ed. United Irishman; his O’Donovan Rossa’s Prison Life: Six Years in English Prisons appeared in 1874 was reprinted as Irish Rebels in English Prisons (1882); he refused to condemn the Phoenix Park assassinations of Thos. Burke and Lord Cavenish by the Invincibles in 1882; JODR returned again to Ireland in 1894 [var 1891] when he unveiled he unveiled a monument to the Manchester Martyrs in Birr, Co. Offaly; Rossa’s Recollections were issued in 1898;JODR visited Ireland again in 1905 to take up job on Cork County Council, but followed his wife back to the United States US when she was stricken with illness, Feb. 1906; unveiled “The Maid of Ireland”, a 1798 memorial, in Skibbereen, Co. Cork [1904]; |

| hospitalised with failing health; suffered loss of hearing and sight at the end; d. on Staten Island, NY, 29 June, 1915 [aetat. 83]; bur. in Glasnevin, Co. Dublin, on 1 Aug. 1915; his body was transported to Ireland in response to Tom Clarke’s cable to John Devoy with the message: ‘Send his body home at once’ received with hero’s welcome by the Irish Volunteers in the IRB propaganda coup; secretly contacted Germany for Irish arms during WWI, defying American neutrality; remains displayed in open coffin for some days in the City Hall and visited there by thousands, with an permanent Irish Volunteers guard of honour; bur. at Glasnevin, 1 Aug. 1915; a funeral Mass was said by Republican priest Fr. O’Flanagan at the pro-Cathedral; a funeral address was made by Patrick Pearse [Pádraig Mac Piarais] - at Clarke’s invitation - speaking in Volunteer uniform at the cemetry in Glasnevin [National Cemetery] of ‘this unconquered and unconquerable man’ with the famous exordium: ‘[...] the fools, the fools, the fools! - they have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace’ - see full-text as attached); that famous and momentous oration was re-enacted in an official commemoration at O’Donovan’s grave in the presence of President Michael D. Higgins and Taoiseach Enda Kenny on 1 Aug. 2015; there exists Pathé footage of the funeral. DIB DIH DIL FDA OCIL |

|

|

|

|

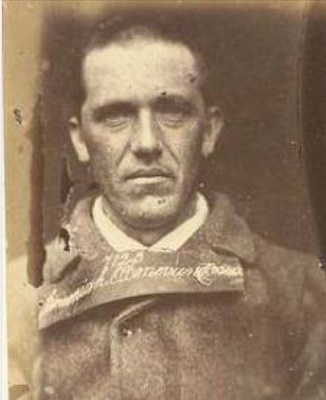

| O’Donovan Rossa, prisoner; his monument in St. Stephen’s Green (photo BS); a Puck Magazine (NY) cartoon of 19th March 1884 [Irish Times, 1.08.2015). |

|

| Members of the Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa Funeral Committee | ||

|

[ top ]

| Autobiography |

|

| Fiction |

|

| [ For a discussion of poetry ascribed to him, see under “A Fenian Ballad” (reputedly by O’Donovan Rossa) - as infra. ] |

Corpus of Electronic Texts: ‘O’Donovan Rossa’, in Political Writings and Speeches (Dublin: Phoenix Publishing Co. Ltd. 1910-1919), at CELT, Univ. College, Cork [Available online.]

[ top ]

Criticism

|

See also Ann Matthews, Renegades: Irish Republican Women 1900–1922 (Cork: Mercier Press 2010), pp.13-14; and a brief account of election victory of 1871 in D. G. Boyce, ‘Separatism and the Irish National Tradition’, in Colin H. Williams, ed., National Separatism (Cardiff: Wales UP 1982), p.89; Patrick Freyne, ‘O’Dynamite’ Rossa: Was Fenian leader the first terrorist?", in The Irish Times ([Sat.] 1 Aug. 2015) [incls. “Gorilla Warfare” cartoon from Puck - available online; accessed 31.07.2020.].

See Colm Tóibín on O’Donovan Rossa in ‘After I am Hanged my Portrait will be Interesting: Colm Tóibín tells the story of Easter 1916’, in London Review of Books (31 March 2016) - as attached.

[ top ]

| “The Returned Picture” | ||

[Mrs. O’Donovan Rossa, while her husband was imprisoned at Portland in 1866, sent him a likeness of herself and her baby, born a week after Rossa’s conviction and accordingly never seen by him. The picture was returned accompanied by a note from the Governor to the effect that the Regulations did not allow such things to prisoners.] |

||

|

Refused admission! Baby, Baby, Ah, you laugh, my little Flax-Hair! |

Was it much to ask them, Baby — Ah, they’re cruel, cruel jailers; |

|

||

| In Gill’s Irish Reciter: A Selection of Gems from Ireland’s Modern Literature, ed. J. J. O’Kelly [Sean Ó Ceallaigh] (Dublin: M. H. Gill 1905), p.242 [available at Internet Archive - online]. | ||

[ top ]

James Joyce - of Mangan’s sister in “Araby”: ‘[...] Her image accompanied me even in places the most hostile to romance. On Saturday evenings when my aunt went marketing I had to go to carry some of the parcels. We walked through the flaring streets, jostled by drunken men and bargaining women, amid the curses of labourers, the shrill litanies of shop-boys who stood on guard by the barrels of pigs’ cheeks, the nasal chanting of street-singers, who sang a come-all-you about O’Donovan Rossa, or a ballad about the troubles in our native land.’ (Joyce, “Araby”, in Dubliners, 1914 &c.)

Pádraic Piarais, Graveside Oration: ‘Do hiarradh orm-sa labhairt indiu ar son a bhfuil cruinnighthe ar an láthair so agus ar son a bhfuil beo de Chlannaibh Gaedheal, ag moladh an leomhain do leagamar i gcré annso agus ag gríosadh meanman na gcarad atá go brónach ina dhiaidh. A cháirde, ná bíodh brón ar éinne atá ina sheasamh ag an uaigh so, acht bíodh buidheachas againn inar gcroidhthibh do Dhia na ngrás do chruthuigh anam uasal áluinn Dhiarmuda Uí Dhonnabháin Rosa agus thug sé fhada dhó ar an saoghal so. Ba chalma an fear thu, a Dhiarmuid. Is thréan d’fhearais cath ar son cirt do chine, is ní beag ar fhuilingis; agus ní dhéanfaidh Gaedhil dearmad ort go bráth na breithe. Acht, a cháirde, ná bíodh brón orainn, acht bíodh misneach inar gcroidhthibh agus bíodh neart inar gcuirleannaibh, óir cuimhnighimís nach mbíonn aon bhás ann nach mbíonn aiséirghe ina dhiaidh, agus gurab as an uaigh so agus as na huaghannaibh atá inar dtimcheall éireochas saoirse Gheadheal.’ (See full-text copy on CELT website [online; extant 15.11.2010], and English trans. as infra.)

Patrick Pearse, ‘O’Donovan Rossa: Character Study’, in Political Writings and Speeches (Dublin: Phoenix Publishing Co. Ltd. 1924), pp.128-33: ‘O’Donovan Rossa was not the greatest man of the Fenian generation, but he was its most typical man. He was the man that to the masses of his countrymen then and since stood most starkly and plainly for the Fenian idea. More lovable and understandable than the cold and enigmatic Stephens, better known than the shy and sensitive Kickham, more human than the scholarly and chivalrous O’Leary, more picturesque than the able and urbane Luby, older and more prominent than the man who, when the time comes to write his biography, will be recognised as the greatest of the Fenians - John Devoy - Rossa held a unique place in the hearts of Irish men and Irish women. They made songs about him, his very name passed into a proverb. To avow oneself a friend of O’Donovan Rossa meant in the days of our fathers to avow oneself a friend of Ireland [128] it meant more: it meant to avow oneself a “mere” Irishman, an “Irish enemy”, an “Irish savage”, if you will, naked and unashamed. Rossa was not only “extreme”, but he represented the left wing of the “extremists”. Not only would he have Ireland free, but he would have Ireland Gaelic. [Cont.]

And here we have the secret of Rossa’s magic, of Rossa’s power: he came out of the Gaelic tradition. He was of the Gael; he thought in a Gaelic way; he spoke in Gaelic accents. He was the spiritual and intellectual descendant of Colm Cille and of Seán an Díomais. With Colm Cille he might have said, “If I die it shall be from the love I bear the Gael”; with Shane O’Neill he held it debasing to “twist his mouth with English”. To him the Gael and the Gaelic ways were splendid and holy, worthy of all homage and all service; for the English he had a hatred that was tinctured with contempt. He looked upon them as an inferior race, morally and intellectually; he despised their civilisation; he mocked at their institutions and made them look ridiculous.

And this again explains why the English [129] hated him above all the Fenians. They hated him as they hated Shane O’Neill, and as they hated Parnell; but more. For the same“crime” against English law as his associates he was sentenced to a more terrible penalty; and they pursued him into his prison and tried to break his spirit by mean and petty cruelty. He stood up to them and fought them: he made their whole penal system odious and despicable in the eyes of Europe and America. So the English found Rossa in prison a more terrible foe than Rossa at large; and they were glad at last when they had to let him go. Without any literary pretensions, his story of his prison life remains one of the sombre epics of the earthly inferno.

O’Donovan Rossa was not intellectually broad, but he had great intellectual intensity. His mind was like a hot flame. It seared and burned what was base and mean; it bored its way through falsehoods and conventions; it shot upwards, unerringly, to truth and principle. And this man had one of the toughest and most stubborn souls that have ever been. No man, no government, could either break or bend him. Literally [130] e was incapable of compromise. He could not even parley with compromisers. Nay, he could not act, even for the furtherance of objects held in common, with those who did not hold and avow all his objects. It was characteristic of him that he refused to associate himself with the“new departure” by which John Devoy threw the support of the Fenians into the land struggle behind Parnell and Davitt; even though the Fenians compromised nothing and even though their support were to mean (and did mean) the winning of the land war. Parnell and Davitt he distrusted; Home Rulers he always regarded as either foolish or dishonest. He knew only one way; and suspected all those who thought there might be two.

And while Rossa was thus unbending, unbending to the point of impracticability, there was no acerbity in his nature. He was full of a kindly Gaelic glee. The olden life of Munster, in which the seanchaidhe told tales in the firelight and songs were made at the autumn harvesting and at the winter spinning, was very dear to him. He saw that life crushed out, or nearly crushed out, in squalor and famine during ’47 and ’48; [131] but it always lived in his heart. In English prisons and in American cities he remembered the humour and the lore of Carbery. He jested when he was before his judges; he jested when he was tortured by his jailors; sometimes he startled the silence of the prison corridors by laughing aloud and by singing Irish songs in his cell: they thought he was going mad, but he was only trying to keep himself sane.

I have heard from John Devoy the story of his first meeting with Rossa in prison. Rossa was being marched into the governor’s office as Devoy was being marched out. In the gaunt man that passed him Devoy did not recognise at first the splendid Rossa he had known. Rossa stopped and said,“John”.“Who are you”? said Devoy:“I don’t know you”.“I’m Rossa”. Then the warders came between them. Devoy has described another meeting with Rossa, and this time it was Rossa who did not know Devoy. One of the last issues of The Gaelic American that the British Government allowed to enter Ireland contained Devoy’s account of a recent visit to Rossa in a hospital in Staten Island. It took a little time to make [132] him realise who it was that stood beside his bed.“And are you John Devoy”? he said at last. During his long illness he constantly imagined that he was still in an English prison; and there was difficulty in preventing him from trying to make his escape through the window. I have not yet seen any account of his last hours; cabling of such things would imperil the Defence of the Realm.

Enough to know that the valiant soldier of Ireland is dead; that the unconquered spirit is free. [133; End.]

[See also Pearse’s graveside panegyric for O’Donovan Rossa at Glasnevin Cemetery on 1 August 1915 under Pearse > Quotations - or as attached; copy text at CELT (UCC) - online.]

Note: Pearse’s graveside oration was re-enacted in an official commemoration at O’Donovan Rossa’s grave in the presence of President Michael D. Higgins and Taoiseach Enda Kenny; this event was lamented by Carla King in a letter to the Irish Times pointing out that Michael Davitt saw O’Donovan as a dangerous buffoon and expressing herself ‘deeply saddening that [...] the first act in our official commemoration of the 1916 events is to honour a man who dedicated his life to attempts to bomb his way to Irish independence’. (See Carla King, letter to The Irish Times, 4 Aug. 2015 - online, and commentary on the issue by Diarmuid Ferriter in the issue for 15 Aug. 2015 - online.)

[ top ]

Jenny Marx, ‘Articles [...] on the Irish Question’, in Marx / Engels on Ireland and the Irish Question, ed. L. I. Golman (Moscow: Progress Books 1986 [edn.]. [Article] III (16 March 1870), gives full account of O’Donovan Rossa’s letter to The Times and the Marseillaise on the treatment of Fenian prisoners in England, and documents the English press response before proceeding to the case of [Col.] Richard Burke at Woking Prison and the lying information of Mr Bruce, the Home Secretary, to enquiries made by relatives and others about his reduction to insanity by the treatment he received (p.483-85); in the next article, she reports George Moore’s question to the Govt. in the House of Commons demanding an enquiry from Mr Gladstone, PM. The ensuing articles are concerned with the Coercion Bill, rounding again on Gladstone in connection with the secret service now established in Ireland: ‘Not even Nicholas of russia ever published a crueller ukase against the unfortunate Poles than this Bill of Mr Gladstone’s against the Irish.’ (p.492.) She continues: ‘We state without hesitation that Mr Gladstone has proved to be the most savage enemy and the most implacable master to have crushed Ireland since the days of the notorious [Robert Stewart] Castlereagh. / As if the cup of ministerial shame were not already full to overflowing, it was announced in the House of Commons on Thursday evening, the same evening as the Coercion Bill was introduced, that Burke and other Fenian prisoners had been tortured to the point of insanity in the English prisons, and in the very face of this appalling evidence Gladstone and his jackal Bruce were protesting that the political prisoners were treated with all possible care. When Mr. Moore made this sad announcement to the House he was constantly interrupted by hoots of bestial laughter’ (P.492.) Note however that Marx writes in a different vein of O’Donovan Rossa, when he tells Friedrich Adolfe Sorge, writing of The Irishman in connection with charges against Joseph Patrick McDonnell: ‘[the] editor, Pigott, is a mere speculator, and whose manager, [William Martin] Murphy, is a ruffian. [...] As to O’Donovan Rossa, I wonder that you quote him still as an authority after what you have written me about him. If any man was obliged, personally, to the Internal and the French Communards, it was he, and you have seen what thanks we have received at his hands.’ (ibid. p.999; ftn. explains that, in America, O’Donovan abused the Communards and accused them of murders.)

Douglas Hyde: Hyde addressed a ‘toast in verse’ to O’Donovan Rossa the Fenian: ‘I drink to the health of O’Donovan Rossa / Where will I find his like at home or abroad, / Who would drive the people without arms or uniforms / Into the midst of the soldiers, the swords and the bayonets. / Who bought and kept the powder and guns / Which he could not send to the poor defenceless people, / Who nevertheless urged our poor unarmed peasantry / To drive the Saxon soldiers away across the sea.’ (See Dominic Daly, The Young Douglas Hyde, 1974, p.47.)

[ top ]

Michael Newton, The Age of Assassins: A History of Conspiracy and Political Violence 1865-1981 (Faber 2012) cites O’Donovan Rossa’s offer of $10,000 to anyone who would assassinate the Prince of Wales in 1887; also his remark, "Burn everything English except their coal" [orig. Jon. Swift], attributed to him by an Ulster policeman in Reynolds Weekly, March 1893.

Colm Tóibín, ‘“After I am hanged my portrait will be interesting”: Colm Tóibín tells the story of Easter 1916’, in London Review of Books (31 March 2016) - ‘[...] In 1867, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), also known as the Fenians, who was serving a life sentence for treason, was moved to Millbank. According to his biographer Shane Kenna, he was regarded as the institution’s most troublesome prisoner; news of the punishments he received for petty infringements of the rules became an important part of Fenian propaganda over the next few years. Two different inquiries took place into the conditions in which he and his fellow prisoners were being held. After the second, it was decided to release the prisoners on condition that they did not return to Ireland. Thus, in January 1871, O’Donovan Rossa arrived in New York; he was greeted as a hero.’ Further:

Among the friends he made in America was Patrick Ford, the editor of the Irish World, a newspaper with a circulation of 125,000. In 1876, Ford and O’Donovan Rossa set up what they called ‘a skirmishing fund’ to assist in the planning and carrying out of a bombing campaign in Britain. ‘Language, skin-colour, dress, general manners,’ Ford wrote, ‘are all in favour of the Irish.’ Ford and O’Donovan Rossa were aware of Alfred Nobel’s dynamite compound, invented in 1867. ‘Dynamite,’ as Sarah Cole wrote in her book At the Violet Hour (2012),

Using the pages of the Irish World, Ford and O’Donovan Rossa collected more than $20,000 within a year. Even those among the nationalist Irish-American groups who supported the idea of a bombing campaign in Britain viewed with dismay the lack of restraint and caution in O’Donovan Rossa’s violent rhetoric. John Devoy, one of the leaders of Clan na Gael, the main Irish nationalist organisation in America, believed, as Kenna writes, that O’Donovan Rossa ‘had given the British ample warning of his plans through a desire for notoriety and theatricality, thus jeopardising any future or current Fenian initiative’. O’Donovan Rossa was defiant. ‘I am not talking to the milk and water people,’ he wrote in the Irish World,

As the arguments within Irish-America became more heated, O’Donovan Rossa began drinking heavily. ‘He is now so bad that I fear the only way to save him is to put him under restraint,’ Devoy remarked, having discovered that O’Donovan Rossa had misappropriated funds. Even when sober, O’Donovan Rossa made himself into a nuisance for Devoy and his colleagues in the United States who were seeking to make an alliance, known as the New Departure, with Parnell and the Irish Parliamentary Party in Ireland. Threatening to dynamite Britain would not be helpful in the effort to create a united movement within Irish nationalism. Increasingly determined, bombastic and indiscreet, O’Donovan Rossa matched his incendiary rhetoric with action. In January 1881 his followers exploded a bomb in Salford, the first time a bomb had been planted in Britain to further a political cause. The bomb destroyed some shops, injured a woman and killed a seven-year-old boy. The British authorities, who began to monitor O’Donovan Rossa’s activities in the United States, observed that he had the ruthlessness of a dangerous conspirator without any of the guile. Micheal Davitt, the leader of the Land League in Ireland, referred to him as ‘O’Donovan Assa’ and called him ‘the buffoon in Irish revolutionary politics with no advantage to himself but with terrible consequences to the many poor wretches who acted the Sancho Panza to his more than idiotic Don Quixote’. Slowly and without much difficulty, the British infiltrated his organisation. Nonetheless, the movement to bomb Britain continued sporadically over the next few years. Its culmination was Dynamite Saturday in January 1885, noted by James in another letter to Norton: ‘The country is gloomy, anxious, and London reflects its gloom. Westminster Hall and the Tower were half blown up two days ago by Irish Dynamiters.’ Eighteen months earlier, a young Irishman recently returned from America, Thomas J. Clarke, one of O’Donovan Rossa’s Sancho Panzas, had been arrested in London. |

| See full-text copy - as attached. |

[ top ]

| “O’Donovan Rossa’s Farewell to Erin” | ||

|

|

|

| —In Colm Ó Lochlainn, ed., Irish Street Ballads (1939). p.68; quoted in Don Gifford, Joyce Annotated [.... &c.] (California UP 1982), pp.45-46. [Note: The poem does not convincingly suggest lines by O’Donovan Rossa so much as a lines about him. see the discussion of the authorship of “A Fenian Ballad” which reaches us with an attestation to its ‘real’ authorship by the patriot himself - as infra. | ||

[ top ]

References

Justin McCarthy, gen. ed., Irish Literature (Washington: University of America 1904); selects ‘Edward Duffy’ and ‘My Prison Chamber’.

|

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2; selects O’Donovan Rossa’s Prison Life [160-63], Rossa’s Recollections 1838 to 1898 [293-65]; with remarks and notes at 211 [funeral], 243n [Pheonix Societies], also 250n, 260, 274-75. 281, 292, 293-94, 708n, 781; 368 [Works, as supra].

[ top ]

Notes

Puck Magazine - a late-19th century American journal known for its anti-Irish sentiments printed a portrait of O’Donovan Rossa with the caption ‘Gorilla Warfare under the protection of the American flag.’ in the issue for 19th March 1884.

Donald Torchiana cites P. H. Pearse, ‘A Character Study: Diarmuid Ó Donnabhain Rosa, 1831-1915’, Souvenir of Public Funeral to Glasnevin Cemetary (Dublin 1 Aug. 1915) in Backgrounds to Joyce’s Dubliners (1986).

Mary Jane O’Donovan [née Irwin, 1845-1916; his wife of 40 years; m. 22 Aug. 1864, with whom 13 children; suspected of funding IRB; resigned from the Ladies Committee for the Relief of State Prisoner [Fenians] which she formed with Letitia Luby - along with Ellen and Mary O’Leary, Mrs Dowling, Catherine Mulcahy, Isabella Roantree, and Jane Stephens - and which raised money for 2,000 men in prison, March 1867; emig. to NY on his advice in 1868; fare paid by Richard Pigott; her last poem was “In Memory of Patrick Pearse”; d. 18 Aug. 1916. (See Wikipedia entry - online; accessed 31.07.2020

[ top ]