Life

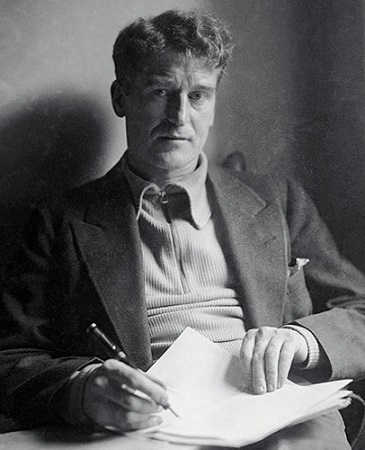

1897-1975 [bapt. Ernest Bernard; var. Earnán Earnan Ó Máille]; b. Castlebar, Co. Mayo, 26 May; son of a Catholic solicitor’s clerk; moved to Dublin on his father’s promotion, and educated there; joined Irish Volunteers 1917 [err. DIH et al. active in 1916 and interned]; sat and failed medical school examinations twice [var. took UCD medical scholarship in 1915 and gave up after the Rising to join the struggle]; joined IRA, 1918; commanded a company in Coalisland, Co. Tyrone; appt. to a roving commission for Michael Collins; IRA organiser of North-West Ulster after 1917; reputedly participated with Eoin O’Duffy in the destruction of the Ballytrain RIC Barracks, Co. Monaghan, Feb. 1920; attached to Sean Treacy’s 3rd. Tipperary Brigade, participating in attack on Hollyford Barracks, 10-11 May 1920; wounded in attack on Rear Cross Barracks, 11 July; captured in Kilkenny under name of Bernard Stewart, held for three months, and tortured by Black and Tans, 1920; escaped Feb. 1921, with aid of boltcutters; |

|

commander of 2nd Southern Division, consisting of five brigades, March 1921; administered Gen. Mulcahy’s orders to cease active operations, Monday, 11th July, 1921; earliest divisional commander to reject Treaty; raided Clonmel Barracks, 16 Feb. 1922; Officer Commanding Headquarters Section of Four Courts garrison with Rory O’Connor, Cathal Brugha, and other republicans (3rd Dublin Brigade) in Civil War, 14 April 1922; triggered off explosion that destroyed Public Records Office by fire; captured and escaped; organised IRA in southern Ireland after his escape from custody, an event omitted in the 1936 edn. of his autobiography; participated in raid on Enniscorthy Castle; Army Council, 16 April 1922; received 21 bullet wounds from Free State soldiers during capture on Ailesbury Rd., Nov. 1922; spared execution with leading Republicans due to wounds; subjected to torture including the firing of a revolver blank at the back of his head; |

|

| read widely in prison (‘mapped out a course of English literature and [...] endeavouring to follow it’, July 1923), and re-espoused Catholicism; undertook 41 days hunger-strike, 1923; elected Sinn Féin TD, N. Dublin, 1923, refusing to take Oath of Allegiance or Dail seat; remained under sentence of death in Mountjoy to July 1924; threatened with life in a wheelchair by his doctor, he undertook a walking tour of Europe on release (learning ‘to use my eyes again in a new way’); travelled in Spain, among the Basques; returned to Ireland and briefly studied medicine, soon abandoned; travelled to America, raising funds for the Irish Press, 1927; organised attacks on poppy wearers in Dublin in the 1920s - specifically in Grafton St. (‘I “did” Grafton Street’ looking at the Poppy wearers and feeling sympathy for them for many had relatives killed I am sure’ - letter of , Nov. 1926) | |

| contrib. pieces for the Sunday Press, later published as Raid and Rallies (1928); supporter of Jack Yeats’s reputation; ill at ease in East-coast Irish-America; travelled in California, working at various jobs; settled in an artists’ colony at Taos (Mexico) with Georgia O’Keeffe and others; drafted On Another Man’s Wounds (publ. serially in Irish Press; 1936) while staying with a family at Taos; received telegram from Frank Aiken on Fianna Fáil coming to power (‘Come home immediately; satisfactory openings available’ (1932); acted as Irish representative at Chicago World Fair (1933); advised to move to New York by photographer Paul Strand; met Hart Crane and Dora Brett; fell in love with Helen Hooker Roelofs, an heiress and sister-in-law of John D. Rockefeller III, late 1935; married in London against her well-connected [Republican] family, 1935; returned to Ireland and settled nr. Newport, Co. Mayo; called to stand for N. Dublin Dáil seat, May 1938; raised three children; suffered an irretrievable marital breakdown - two children (Cathal and Étain) being removed [‘kidnapped’] by his wife, leaving his son Cormac in his charge, 1950; | |

| auctioned his library at Sotheby’s in 1949, and amassed another of 4,000 by 1953; became a close friend of Jack B. Yeats in later life, and collector of his paintings; contributed a memoir of Jack Yeats to a collection edited by Roger McHugh (1945); he was an early champion of Louis le Brocquy [q.v.]; elected MIAL 1947;d. 25 March 1957; The Singing Flame (1978), an autobiographical sequel, was edited by Frances-Mary Blake from papers held in UCD; also Raids and Rallies (1982), first published as articles in the Sunday Press in the 1950s, covering attacks on the RIC in counties Tipperary, Roscommon, Clare and Mayo; his MS biography of IRA-commandant Sean Connolly of Co. Longford was issued posthum. in 2007; his interviews with IRA veterans are held in the UCD Archives; his copious letters, memoranda, and orders from June 1922 to May 1923 were issued as No Surrender Here! (2009), edited Anne Dolan and Cormack O’Malley [his son]; Raids and Rallies was reissued in 2011; there is an Ernie O’Malley symposium at Glucksman House (NYU); his art collection in Dublin sold for €5.5 million on 25 Nov. 2019 (Whytes/Christie); a new life by Harry F. Martin and Cormac K. H. O’Malley was launched by Merrion Press at Hodges Figgis, 13 Oct. 2021. DIW DIB DIH DUB | |

[ Go to Ernie O’Malley website - www.ernieomalley.net. ]

|

[ top ]

Works| Autobiography |

|

|

|

| Biography |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| Letters & papers |

|

| Edited volumes |

|

[ top ]

Criticism| Major studies |

|

| Studies |

|

| Reviews |

|

Note also David Lloyd, ‘On Republican Reading: Ernie O’Malley, Irish Intellectual’, in the Moore Institute Seminars Series (NUI Galway), 6 Nov. 2008 [seminar timetable at Moore Inst. online; accessed 26.04.2009]. |

|

[ top ]

| “Sculptured Lives” - An Exhibition |

Helen Hooker (artist) Ernie O’Malley (soldier/writer) Sculptured Lives presents sculptured heads and figures, drawings, paintings, photographs and letters spanning over 50 years of Helen Hooker’s artistic career. On view are books, letters, photographs and ephemera that tell the story of Helen and her Irish husband, IRA Commandant-General Ernie O’Malley, the soldier and writer. Also included are some of his books and rare letters to him from Eamon deValera and his artist friend, Jack B. Yeats. A highlight of the exhibition is a rare film interview with Helen Hooker in 1973 and a recent documentary of Ernie O’Malley that premiered on TnaG, Irish Television. Runs to mid-January 2010 at Consulate General of Ireland, 345 Park Avenue, 17th Floor. [“The Green Apple - A Sense of Ireland” - Ireland Embassy Notice - online; accessed 04.07.2011. |

[ top ]

Commentary

Richard Kain (Dublin in the Age of William Butler Yeats and James Joyce (1962; 1972), calls On Another Man’s Wounds ‘the outstanding literary achievement of the Anglo-Irish war, by a field-officer, Ernie O’Malley’ (Sel. Bibl. p.203).

But see ...

Sean Murphy, Guide to the National Archives of Ireland (2009): ‘[...] The most devastating event in the history of public record keeping in this country was undoubtedly the destruction of the bulk of the contents of the Public Record Office of Ireland during the Civil War in June 1922. The range and quality of the records lost can be adduced from Woods’s guide, published only three years before the act of destruction. (1) Documents dating from Anglo-Norman times onwards were entirely obliterated or reduced to a fragmentary state, including journals and papers of the Irish Parliament, masses of State Papers, records of the courts, and ecclesiastical, testamentary and census records. The Anti-Treatyite Ernie O’Malley, one of those responsible for the vandalism of 1922, wrote pretentiously of the event in his memoirs, “Flame sang and conducted its own orchestra simultaneously”. (2) The holocaust of national records was the result of innate disregard for archival heritage on the part of both sides in the Civil War, and it has to be said that in a country where imagination tends to outweigh documentation, O’Malley’s careless attitude has still not entirely disappeared. Although the Public Record Office of Ireland was revived after 1922, it was never given resources adequate to the task of reconstruction, a legacy of neglect under which the National Archives has also laboured. / It has been rightly pointed out that another consequence of the devastation of 1922 was the entrenchment of the idea that this country does not really require a major national archival repository. The National Archives Act 1986, under which the National Archives was established, represented a belated attempt to bring Ireland’s public archival policy into line with those of other developed countries. [....]’ (Centre for Irish Genealogicaland Historical Studies [2009]- online; accessed 3.11.2011)

[ top ]

D. George Boyce, review of Prisoners, ed. Richard English & Ernie O’Malley, in Irish Political Studies, VII (1992): ‘O’Malley freely admitted that he possessed no administrative or governmental training, no plan of how he and other republicans might use the independent Irish state to achieve their goals. He declared that he could never become a TD again, because of their lack of “spirituality”. But it must be confessed that, while indeed Ireland’s TDs do not strike even the most impartial observer as a spiritual bunch, they are the stuff of which democratic politics are made. Revolvers and Eng. Lit. were no preparation for creating a stable Ireland.’ (p.125; quoted in Richard English, ‘“The Inborn Hatred of Things English: Ernie O’Malley and the Irish Revolution, 1916-1923’, in Past and Present, May 1996, p.192.)

Richard English, ‘The IRA’s Richard Hannay, Ernie O’Malley, John Buchan, and the Irish Revolution’, in Causeway, Cultural Traditions Journal (Summer 1994), pp.29-34, remarks on O’Malley’s use of Hannay-type language, and writes of O’Malley’s place in overwhelmingly male culture, characterised by forms of rather patronising chivalry towards women which glorifies courage, adventure, and the countryside [and] demands the reader accepts the unquestionable righteousness of their hero’s struggle. ‘John Buchan is an ideal figure through whom to read O’Malley, a British writer whose thrillers reflected that same Stevensonian romanticism upon which O’Malley himself so eagerly fed …’. (p.33.) English goes on to note the influence of contemporary British modes of romance on IRA-men such as Tom Barry and Peader O’Donnell; commences with citation from On Another Man’s Wounds (1929) referring to the author’s having shared ‘the pseudo-military mind of the IRA and its fear of constitutional respectability’, and some further quotations reflecting O’Malley’s unwillingness to countenance a political career. The core thesis of the essay concerns a professed admiration of O’Malley for the Scots imperialist adventurer, especially in details such as their condescending chivalry towards women. Refers to what Roy Foster has called ‘the epic image of Ireland conjured up in emigration’. Besides Wounds and Singing Flame, also cites Raids and Rallies; emphasises O’Malley’s professed admiration for Rupert Brooke as well as Patrick Pearse. [Cont.]

Richard English (‘The IRA’s Richard Hannay, Ernie O’Malley, John Buchan, and the Irish Revolution’, 1994) - cont.: English quotes O’Malley: ‘The development of the sense of duty and responsibility and of sacrifice was a hard doctrine to teach – that of duty, perhaps, hardest. If a man does his duty he is happy in the doing of it and that is his reward’; the old IRA [had] ‘always fought clean’ (1923); ‘The [Free] Staters are awful rotters to fire on girls’ (Feb. 1923); ‘It’s rather rotten that those Staters should be so nasty to women’; ‘The marriage disease is spreading; a good number of my staff are down with the disease so my temper is not improved’; ‘The country has not had, as yet, sufficient voluntary sacrifice and suffering and not until suffering fructuates will she get back her real soul’; ‘Then came like a thunderclap the 1916 Rising’; ‘We are in the tradition of Tone and Pearse’ (Aug. 1922) [&c.] Bibl., Richard English & C[ormac] O’Malley, eds., Prisoners, The Civil War Letters of Ernie O’Malley (Dublin: Poolbeg 1991); English, ‘Green on Red, Two Studies in Early Twentieth Century Irish Thought’, in D. G. Boyce, et al., eds., Political Thought in Ireland Since the Seventeenth Century (Routledge 1993).

Richard English, ‘Revolutionary Writing’, in Fortnight, 404 (May 2002), quotes O’Malley, ‘I yet have the feeling of not justifying my existence when I don’t write something’, and remarks: ‘The words of IRA writer and fighter, Ernie O’Malley, in 1934. After his 1916-23 revolutionary adventures, he’d spent more time with books and bohemians than with guns or explosives, but he hadnt stopped being a republican. His classic autobiographies […] contributed lastingly to the Irish republican cause, recreating in print the vision which had inspired him in the mythic post-1916 years of struggle.’

English goes on to compare him with Peadar O’Donnell and writes that ‘both men […] had diverse and wide interests and between them wrote about art and people, about relationships and travel, about painting and poverty.’ the remainder of the article is concerned with more recent Northern Irish Troubles and the writers Patrick Magee and Danny Morrison. (Fortnight, pp.22-23.)

Richard English, ‘“The Inborn Hatred of Things English: Ernie O’Malley and the Irish Revolution, 1916-1923’, in Past and Present, 151 (May 1996), 174-99. ‘In August 1937 Lennox Robinson wrote to Ernie O’Malley informing him that his name had been proposed (by Sean O’Faolain) and seconded (by Frank O’Connor) for membership of the Irish Academy of Letters.1 In his autobiography My Father’s Son, O’Connor recalled that after a meeting of the Academy at which he and O’Faolain had been trying to get O’Malley elected they had gone to the house of W. B. Yeats: “Yeats greeted us with his Renaissance cardinal’s chuckle and asked: ‘What do you two young rascals mean by trying to fill my Academy with gunmen?’” O’Malley might well have enjoyed such an exchange. ֻI don’t mind being called a gunman”, he wrote to Desmond Ryan in 1936] “we were, I suppose, though we didn’t use that term ourselves”. This article is about a gunman.’ (p.174.) [...] ‘If one accepts Linda Colley’s argument that Britishness was built on the strongly connected foundations of Protestantism, profits and war, then it is not difficult to trace the contours of the nationalist Irishness which developed so powerfully in the early twentieth century. In broad terms, the perceived marginality of Catholic Ireland within the United Kingdom provided the soil from which the new nationalism could grow. The political demarcation between the more Protestant north-east of the island - where Irish nationalism failed to gain the day - and the rest of the island owed much to a religiously coloured sense of history, identity and allegiance. Irish republicanism in the 1916-23 period was a form of Catholic nationalism.’ (p.175-76) [...] ‘Against this background it is possible to trace with precision O’Malley’s developing involvement with militant Irish republicanism.’ (p.177.) [...] Liah Greenfeld has recently argued that the historical development of nationalism can best be explained by means of the concepts of prestige and resentment, combined with the elements of inferiority and emulation which have characterized the relations between nationalists of different countries. [...] Shifts in domestic elites, the redefinition of social hierarchies, the prestige-bestowing qualities of a new nationalism, considerable resentment towards England (coupled with a telling weight of influence and emulation, and significant evidence of a sense of inferiority) have each a crucial part to play in helping us to understand the Irish Revolution. In O’Malley’s case the “inborn hate of things English” coexisted with a very marked degree of British influence, and indeed with an occasional sense of “the superiority of the English” [E. O’Malley to S. Humphreys, 10 Apr. 1923, in O’Malley, Prisoners, ed. English and O’Malley, p.36.] and the Irish Revolution was undoubtedly set against the background of shifting elites and hierarchies. The remainder of this article will explore these themes in further detail under two broad headings, those of Britishness and soldiership.’ (p.179.) [...] Available as PDF at St. Andrews University / Staff Resources - online

Roy Foster, ‘Varieties of Irishness’, in Cultural Traditions in Northern Ireland: Varieties of Irishness [Proceedings of the Cultural Traditions Cultural Group Conference], ed. Maurna Crozier (Belfast: IIS 1989): ‘The Irish identification with the land, its unique appearance, its light and shade, also owes much to English-derived romanticism (a sensation which one paradoxically receives even through tests like Ernie O’Malley’s lyrical descriptions of bivouacs in the Tipperary mountains in On Another Man’s Wound) […’; &c.] (p.11.)

[ top ]

John McGahern, ‘In pursuit of a single flame’, review essay on ‘neglected classic of the War of Independence’ (Irish Times, 17 Feb. 1996, Weekend, p.8: McGahern identifies O’Malley’s family are British and Catholic, the eldest boy being an Army cadet; at the time of the Rising, Ernie was studying medicine and thinking of joining him; for O’Malley the Rising was decisive, and he joined the First Dublin Batt. of the Volunteers and began drilling; volunteered for full-time duty and given command of Coalisland Company as Second Lieutenant; rapidly promoted; trained men throughout the country; his upbringing ‘make him half an alien among his own people’; ‘A quixotic code of honour was brought to what was mostly a mean struggle’; McGahern identifies a passage in which O’Malley is brought after torture to the house where he was captured, now razed, in the expectation of summary execution: ‘I was not afraid of death now. Faces I knew came up, my brother Frank’s, Sean Treacy’s; then I felt at peace. It was hard to pin anything down, to think I was going to die on the roadside. I would tell them that they were fools, that they could not win; dead men would help to beat them in the end.’ McGahern remarks that he knows of ‘no more powerful expression of that spirit which turns revolt into revolution that this passage’; recounts escape from Dubin Castle, and refusal of Paddy Moran to escape in the belief that he would be acquitted, though later hanged; command of Second Southern Division; execution of three British officers in reprisal punctiliously performed; ‘he had little sense of the complications of history, the necessary compromises. When young, he had absorbed a myth was was prepared to follow it, like a single flame. […] The work as a whole has imaginative truth.’

John McGahern, review article on Ernie O’Malley, On Another Man’s Wounds, ed. & annot., Cormac K. H. O’Malley [enl. rep. edn.] (Anvil 2002): Joseph O’Doherty, Derry-born barrister and Donegal TD, charged that he had been presented in a cowardly and dishonourable light; libel trial in Dublin resulted in O’Malley borrowing Ł400 to pay damages and withdrawal of the book, 1937; paperback republication in 1960; republ. by Dan Nolan and Rena Dardis (Anvil Books 1979); State funeral, 1957. O’Malley travelled to US with Frank Aiken to raise money for Irish Press, but remained to live in artistic communities of California, New Mexico, and Peru; met with Hart Crane in June 1931; returned to Ireland 1935; The Singing Flame, post., ed. Frances Mary Blake; ‘Francis Stuart has claimed a greater significance for the latter book but I find it has neither the spirit nor coherence of the first book. Throughout, there is a pervasive and confused longing for the clarity of action, as if action itself could bring clarity to the futility and bitterness of friends and former comrades fighting one another.’ McGahern recounts that when teaching in Clontarf he found a schoolboy in his class exercises on the free sides of a large notebook filled with O’Malley’s writing. Quotes On Another Man’s Wounds: ‘My lips were dry: they were of rough leather. I had been trying to say some prayers, but could not. My thoughts ran on ahead crossed and recrossed. I was not afraid of death now. Faces I knew came up, my brother Frank’s, Sean Tracey’s [sic]; then I felt at peace. It was hard to pin anything down, to think I was going to die on the roadside. I would tell them that they were fools, that they could not win; dead men would help to beat them in the end.’ McGahern remarks: ‘I cannot answer the accusation that O’Malley altered historical fact for his purposes but I but that the few short sections of the material with which I am well-acquainted - the area around Lough Key and the portrait of Patrick Moran, who was hanged in 1920 - are accurate.’. Further, ‘The work as a whole has imaginative truth. What is extraordinary is that so much of this fascinating material is so well-written.’ McGahern professes that he would be happier to see ‘some of the more self-conscious descriptive passages removed as well as the folkloric ending, which is at odds with the whole tenor of the book […]’. (The Irish Times, 8 June 2002, Weekend, p.10.)

[ top ]

Caoimhe Ni Dhaibhéid, review of Raids and Rallies, in The Irish Times (19 Feb. 2011), Weekend, p.12: ‘[...] Although O’Malley is not alone among IRA memoirists – Tom Barry and Dan Breen are among his most commercially successful comrades – his writing is marked by a lyricism and sensitivity not commonly found elsewhere. In a series of effective pen-portraits in Raids and Rallies , O’Malley’s perceptive and empathetic reading of his comrades comes particularly to the fore, alongside a heightened awareness of the natural world, the elements and the landscapes of Ireland, and the manner in which each of these shaped the conflict that he elsewhere termed “the scrap”. / O’Malley’s enthusiasm for action is one of the strongest features of the first half of the book. Among the most striking pictures to emerge is that of a scorched and charred O’Malley on the roof of Rineen barracks, pouring paraffin down into the rooms below. The burning of RIC barracks, often cursorily cited as a key component of the successful IRA campaign, is here the focus of the book’s most affecting chapters: the lengthy and painstaking preparations; the dangers experienced by Volunteers carrying buckets of sloshing petrol across burning roofs; the later innovation of a makeshift hose to spray fuel directly onto the blaze; and the vivid images of republican figures illuminated by leaping flames against the night sky, which O’Malley characteristically likened to a Caravaggio painting. / What it must have been like in the smoke-filled rooms of the barracks is not entered into, nor does O’Malley spare much consideration for the Crown forces, aside from a pointed reference to having “roast peeler for breakfast”. The Royal Irish Constabulary are dismissed as “Janissaries”, while the casual brutality of the Black and Tans is emphasised throughout, particularly during the infamous reprisals exacted upon the civilian population of West Clare. / O’Malley’s concern throughout is for his comrades; what he terms “a veritable litany of names of men” emerges from the pages, among them Ned Reilly, Jack “the Master” Ryan, Jim Gorman, Ryan Lacken, Paddy O’Brien and Pat Madden. The imperative of naming the ordinary participants is part of O’Malley’s project of recognition for the rank-and-filers, the country folk and the mountain men who gave the revolution its real drive, far away from the streets of Dublin. Although O’Malley does not place himself centre stage, something of his personality emerges; his admiration for the hillside men and their taciturn nature, their laconic humour, and their distrust of “talk” or gossip is perhaps unintentionally revealing.’(Full text available at The Irish Times - online; accessed 03.07.2011.)

Breandán Mac Suibhne, ‘Walking away from the dead: what the Famine did to Ireland’, in The Irish Times (25 Nov. 2017): ‘At the end of October 1918 Michael Collins came out of the Sinn Féin ardfheis, at Mansion House in Dublin, with a scarf wrapped around his chin. Avoiding members of the detective division, he met with Ernie O’Malley, who at only 21 was among the most effective organisers of the volunteer companies that were becoming the IRA. / Collins took him to Cullenswood House, in Ranelagh, where Patrick Pearse had kept his first school. And there, in the dugout - a cellar or storeroom that Collins used as an office - the two of them pored over a map spread out on a big wooden table. It showed Donegal. O’Malley was being sent north. “You’ll freeze to death up there,” Collins said. / O’Malley came north. His name became Gallagher. In places people thought that Gallagher was his real name, and they called him Kelly. He was to spend four months in Donegal, mainly in the west of the county, around Ardara and Glenties, the Rosses and Gweedore, trying to put some shape on young fellows who, with scarcely any weapons, had determined to fight an empire. / “Donegal was not good,” he would later write; “the material was there, but they had no leaders ... Inspection parades were no index of the ordinary. I knew that every effort would be made to have a good muster, men from neighbouring companies would be lent surreptitiously; a GHQ officer was an event; at councils, where I listened to and noted their reports, figures were often cooked.” [.../] But O’Malley liked the people, and in On Another Man’s Wound, from 1936, he wrote evocatively of the conversations in the houses where he billeted: “‘A stranger’ I was spoken of in their houses. It would be easy for information to be brought to the police, but though the people talked much amongst themselves, as if making up for lost time when they met, yet there were walls between them and the outside world. Tales of the Spanish Armada, ships that had been wrecked off Arranmore; stories of the O’Donnells and Fionn; ghost stories with the by-ways of elaboration so that with a wrench “to make a long story short” they came back to the subject; spirits, good and bad, left at cockcrow. The dead walked around, there was an acceptance of their presence, no horror and little dread, the wall was thin between their living and their dead.”’ [The remainder of the article is about folk-lore collectors and their experience of old people who wish to transmit their songs and stories before their own encroaching deaths - and the end of the rundale system the beginning of global emigration.] (Available online; accessed 25.11.2017.)

[ top ]

Quotations

On Another Man’s Wound (1936): ‘Many of us could hardly see ourselves for the legends built up around us. The legends helped to give others an undue sense of our ability or experience, but they hid our real selves; when I saw myself as clearly as I could in terms of myself, I resented the lengend. It made me other than myself and attuned to act to standards that were not my own. That was different from the other subordination of oneself to the movement. / We brought off a good ambush at Drumkeen with the Mid Limericks - a lorry of Tans. Man, we rose them off the road with bullets; we killed eleven of them. [...]’ (Quoted on Irish History Podcast, 22 July 2015; accessed via Facebook, 26.07.2105.)

On Another Man’s Wound ([1936] (Lilliput 2013): ‘We started off in ponies and traps, strung out at intervals. We lifted the cars across trenchesand through gaps where the roads were blocked with heavy, fallen trees. We hauled and pushed them across streams where the bridges had been smashed, we removed heaps of stonesor networks of boulders strewn over a long stretch of road. We bumped over filled-in trenchesand lurched into deep pot-holes. We halted from time to time on rising ground to look towardsthe town. At first we could see a faint haze, the lights of Mallow, then it dimmed as wemoved on; nothing had happened. Later we saw a dim glare; but as we watched it seemed to disappear. Could it be the town? (pp.245-46.)

Further: ‘Police and military shot prisoners: “Shot whilst trying to escape” was their explanation. At inquests verdicts of wilful murder were returned against them. Raids became more destructive, and rings, watches, and valuables disappeared. Officers wore masks on their faces and Tans used blackened cork when they came at night to shoot men who were on their Black List; bloodhounds sniffed whilst the family cowered. The destruction of creameries continued. Police and Tans were shot down on the streets by the IRA; houses which police or military were about to turn into posts were burnt.’ (pp.218-19.) [The foregoing quotations from the 2013 edition quoted in Spurgeon Thompson, review of On Another Man’s Wound, ed. by Cormac K.H. O’Malley, in The Irish Revew (21 Sept. 2013) - available online.]

The Singing Flame (London: Anvil 1978): ‘In general, the local I.R.A. companies made or marred the morale of the people. If the officers were keen and daring, if organization was good, if the flying columns had been established, and if the people had become accustomed to seeing our men bearing arms openly, the resistance was stiffened. When the fighting took place, the people entered into the spirit of the fight even if they were not republican, their emotions were stirred, and the little spark of nationality which is borne by everyone who lives in Ireland was fanned and given expression to in one of many ways.’ (p.11; quoted in Richard English, ‘“The Inborn Hatred of Things English: Ernie O’Malley and the Irish Revolution, 1916-1923’, in Past and Present, May 1996, p.183-84.)

The Singing Flame (London: Anvil 1978): ‘I felt pity for the Staters moving in a vicious circle, as I say them, being driven themselves by their own acts in the course of empire, helped perhaps by our propaganda and abuse, to depart further and further from their ideals. The whole situation looked more like a Greek tragedy. I could myself now dissociate as a player and look on others without passion. Always I had, so I thought, fought impersonal without hatred. I had given allegiance to a certain ideal of freedom as personified by the Irish Republic. It had not been realised except in the mind. I had fought against the British Empire in defence of that Republic, against Irishmen in the RIC, Englishmen in the British Army, and Irishmen in the Free State Army. To me they meant the same system which had stifled the spiritual expression of nationhood and had retarded our development, which had dammed back strength, vigour and imagination needed in solving our problems in our own way. The spirit of the race was warped until it could express its type of genius. Lying in bed, I had doubts about our course of action in resisting the attack of the Free Staters on the Four Courts; I wondered if any other solution have been reached. Doubts did not last. Whatever alliance could have been made with Collins, civil or military, some section of the country would possibly have fought, and I knew that I would have joined them.’ (pp.213-14.)

Further [in the course of ex tempore remarks on the river Shannon spoken under observation by prison guards during armament lectures]: ‘I remembered fords I had talked about with old people, and the stretch where O’Sullivan Beare must have rafted in 1603.’ (Ibid., p.288.) [For remarks on George Russell, infra.]

Mental fight: ‘Every one of our little fights or attacks was significant, they made panoramic pictures of the struggle in the people’s eyes and lived on in their minds. Only in our country could the details of an individual fight expand to the generalisations of a pitched battle. What to me was a defeat, such as the destruction of an occupied post without the capture of its arms, would soon be sung as a victory. Our own critical judgements which adjudged action and made it grow gigantic through memory and distance, were like to folklore. to an outsider, who saw our strivings and their glorification, this flaring imagination that lit the stars might make him think of the burglar who shouted at the top of his voice to hide the noise of his feet. Actually the people saw the clash between two mentalities, two trends in direction, and two philosophies of life; between exploiters and exploited. Even the living were quickly becoming folklore; I had heard my own name in song at the few dances I attended.’ (On Another Man’s Wound, Tralee 1979 ed., p.317; quoted in R. F. Foster, Modern Ireland, [1988], p.501, and there called ‘a characteristic reflection’ from ‘a temperamental irreconcilable if ever there was one’.)

Sligo town: ‘The town presented knowledge of character and incident, the vagaries of personalities with oddities even to the daft accepted as part of its world. It would be an open book like any other Irish town, whose inhabitants are mainly interested in motive and intention of others, in knitting daily events in a conversational form to be related before evening as direct or indirect implication threaded by affection, malice or envy.’ (“The Paintings of Jack B. Yeats”, in Jack B. Yeats: A Centenary , ed. Roger McHugh, Dolmen Press 1971. [n.p.]; quoted in Declan J. Foley, , ed. & intro., The Only Art: Jack B. Yeats - Letters from his Father [...; &c.], Lilliput 2008, p.14.)

[ top ]

References

Belfast Public Library holds On Another Man’s Wound (1936) [quoted under ‘present title’ as Army Without Banners, pbk. ed. 1967, in F. S. L. Lyons, 1971].

There is a Wikipedia page and an Ernie O’Malley website - online.

See also Christie’s notice of the sale of paintings in O’Malley’s personal collection oincluding works by Jack Yeats, Mainie Jellett and Maurice MacGonigal (Nov. 25 2019) - online; accessed 28.02.2021.)

[ top ]

Notes

Jackie Clarke Library, Ballina, Co. Mayo, contains books and papers of Ernie O’Malley (see History Ireland, May 2006, p.7.)

Etain O’Malley, ed., The Irish Sculptures of Helen Hooker O’Malley Roelofs 1905-1993 (1993) exhibition in Univ. of Limerick, Sept 1993, four heads being subsequently housed in Glucksman Ireland House, NY University by permission of her executors; former US Junior Tennis Champion; eloped to marry Ernie O’Malley, 1935; lived with him in Dublin and Mayo, and bore three children; remarried in America in the 1950s, and spent half her time in Ireland after; establish O’Malley Art Award and Collection, part on loan to Municipal. and part looked after by Mayo County Council.

Dublin Guilds: The rolls of membership of the guilds were destroyed in the Public Records office fire [Four Courts, 1922], so it is impossible to determine how many catholics were members of them. (See Maureen Wall, Catholic Ireland in the Eighteenth Century, ed. George O’Brien, Geography Publications 1989, p.179.)

Namesakes: note the author of a life of Cecil Alexander, hymnist - Ernest W[illiam] O[’Malley] Lovell, A Green Hill Far Away: The Life of Mrs. C .F. Alexander (Dublin ASPK/London: SPCK 1970), 84pp.; also Ernest R. O’Malley, author of “Autumn” and “A Fantasy”, songs, with words by M. Ogle (London: Weekes & Co. 1915).

[ top ]