Life

(George Whitfield Pepper;) b. 11 July 1833, Co. Down, N. Ireland; son of Nicholas and Rachel [née Thornburg] Pepper; educ at the (Royal) Belfast Academical Institute; became involved in the Temperance Movement and befriended the Young Ireland leadership incl. notably Thomas Francis Meagher [q.v.]; m. Christina Lindsey in 1853, with whom six children (George, Samuel Arthur, Charles M., Lena, May, Carrie); emig. to America with his wife in 1854; entered Kenyon College, Ohio, and ordained in Methodist minister; recruited the 80th Ohio (Volunteer) Infantry, acting as captain, in the Civil War; returned to the regiment as Chaplain having been disabled in action; appt. Chaplain of the 40th Regulars Infantry (USI) after the War, 1867; he was in constant correspondence of Meagher until the latter’s death in 1867; Pepper worked strenuously for the cause of Ireland against British rule and persuaded a Methodist conference to express official disapproval the execution of the Manchester Martyrs in Salford Gaol, on 22 Nov. 1867; remained active as church minister in Ohio for forty years; d. Cleveland, Ohio, 6 Aug. 1889 and bur. in Lake View Cemetery there, with a monument and the inscription: ‘Chaplain, Student, Pastor, Soldier, Orator, Consul and Author, the champion of the liberty of his native country [i.e., Ireland], he gave his sword to his adopted country. His life testified to the belief in the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man.’ |

|

| [ See note on “Two George Peppers” under George Pepper (1792-1837) - as infra. ] | |

[ top ]

Works

|

| Miscellaneous |

Pepper is cited in a letter sent by Dr. William Carroll to John Devoy regarding the Australian Prisoners Rescue, an upcoming Fenian Convention, and a letter from John O’Leary (29 April 1876) and similar letters in the John Devoy Collection relating to his sympathy with the IRB.] |

[ top ]

|

|

Rev. Geo. W. Pepper, author of the very eloquent address on Ireland’s Martyrs, which was published in full in the Pilot, some weeks since, is also a native of the Green Isle. He was educated partly at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution, and partly at Glasgow. In his native land, he won honorable distinction, as an earnest and eloquent advocate of the cause of temperance. To him, belonged the honor of having founded there, the Maine Law League, of which he was, for two years, corresponding secretary. He had a sharp controversy on the subject of legal prohibition with Dennis Holland, Esq., then editor of the Ulstermcm. He succeeded in calling attention to the terrible evils of intemperance and the necessity of adopting some measures to prohibit the indiscriminate sale of liquors. The first grand meeting, under the auspices of the Maine Law League, was held in Belfast, which was attended by the well known Philanthropists of Dublin, James Haughton and Richard Allen. The organization of branch societies became quite popular. Mr. Pepper was appointed a delegate to the mass meeting, held in Manchester in 1853, at which were present, John Bright, Richard Cobden, James Silk Buckingham (an author of numerous books of travels, and an old friend and correspondent of Mathew Carey, of Philadelphia) who cast all their weight and influence in favor of the temperance reform. [...] Mr. Pepper emigrated to the United States in 1854; and immediately entered Kenyon College, Ohio, for the purpose of studying theology. In due time, he was ordained a minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church; and during the few years preceding the commencement of the Civil War he served his church, most zealously, in the missionary field of labor. On the outbreak of the late civil war, in 1861, as an enthusiastic Irish-American, devoted — like the mass of his' element in these States — to the union and institutions of his adopted country, Mr. Pepper, minister though he was of the Gospel of peace, felt obliged by his convictions and duty to give all the aid in his power to his government. He recruited several hundred men for the loyal armies. He was chosen captain of a company of infantry, and chaplain of his regiment, 80th Ohio volunteers, at the same time. He declined the chaplaincy, and led his company into the field of action. During the campaigns in the Mississippi Valley, he was disabled, and forced to resign the command of his devoted band of “soldiers of freedom.” His resignation had been scarcely accepted, when he was unanimously elected chaplain of the regiment for the second time. As chaplain, he continued with the command to the close of the war. He participated in the great “March to the Sea,” and [32] thence northward through the Carolinas and Virginia, of the army of General Sherman. Of this famous “flanking movement,” he wrote and published an interesting history, which has been highly commended by Secretary Stanton, as also by Major Generals Logan, Howard, McCook, and others. About a year since, Mr. Pepper, on the recommendation of his personal friend, and fellow Irish-American, was made a chaplain of the Regular Army, and assigned to duty on the field staff of the 40th U. S. Infantry. The appointment was given to him in consideration of his personal gallantry in several battles, and indefatigable devotion to the sick in hospitals, &c. As an Irish-American, of warm and generous impulses, Mr. Pepper has taken a deep interest in the movement of the Fenians to release and exalt their down-trodden fatherland. He met with much hostility from his Church, and also from its Bishops, ministers, members and newspaper writers, because of his military propensities, his devotion to the cause of the Union; and, above and beyond all else, because of his active sympathy with the Irish Republican leaders. His motives were impugned; his character was assailed; and, to “ cap the climax “of abuse, he was invidiously denounced as “a Jesuit in disguise.” Nevertheless, he kept on his way unflinchingly, and ultimately so completely triumphed over all opposition, that he had the gratification of witnessing the adoption, by a whole conference of two hundred Methodist preachers, with its presiding Bishop, of a series of resolutions written by himself, and expressive of sympathy with the Fenians in Ireland. In the agitation relative to the rights of naturalized citizens, now in progress, Chaplain Pepper has taken an active part. He has been in constant correspondence on the subject, and on the kindred topic of the sufferings and claims of his race, with Senators and Representatives; and with officials of high rank generally, including Senators Wilson and Chandler, Representative Logan and Chief Justice Chase. In this way, though in official employment in the military service of his adopted country, he has endeavored to the utmost of his fine ability, yet limited opportunity, to discharge his obligations to his native land. The headquarters of his command having been, for some time past, at Goldsboro, N.C, this eloquent Irish- American there made it his duty to deliver in the presence of an alien body, and in a Baptist church, the magnificent discourse which entitles him to the lasting gratitude of his “countrymen in exile.” His noble “record” is eulogy most meet for this gifted, zealous, and patriotic Irish American. |

| Available online; accessed 08.05.2024. |

[ top ]

Ireland .. Liberty Springs from her Martyrs’ Blood, An Address by the Rev. George W. Pepper, Chaplain U.S.1, Delivered at Raleigh, North Carolina, Dec. 20th 1867 (Boston: Published by Patrick Donahoe 1868).

Mr. President: You have done me the honor to request that I should speak to-night on “Ireland,” and I consider, therefore, that it is my duty to put you in possession of my opinions on a subject that is now agitating the British Government, and will continue to agitate until justice is done to the Irish nation — a justice demanding the utter destruction of that flag which has floated for centuries over the bones of a murdered people. My theme, then, is Ireland, the land of our affections and our hopes. There was a time when it was considered an evidence of utter degradation for a man to avow that he was a native of that distant and beloved isle. There was a time when, even in your beautiful city of Raleigh, the irresistible pen of a distinguished politician, a name known and honored throughout the land for staunch fidelity to the Union and civil liberty, had to be wielded in vindication of the rights of foreign born citizens under the Constitution and the laws. Thank God — and I say it with a rejoicing heart — those dark periods have passed away, and the thinking men of all classes are now eager to do justice to that country, to which much of the prosperity and glory of this great nation is due. Ireland, heroic, illustrious island! — once a word of reproach, veined with sneering irony, only spoken of by some religious bigot in a sermon, or by some marrowless politician on the stump to cover it with slander and abuse. [...; p.3]

Geographers tell us that the world may be divided into two hemispheres, one of water and the other of land. Ireland is the centre of the land hemisphere. A most admired poet says “that her back is turned to Britain, and her face to the West,” indicating that Ireland is favorably situated to become the great entrepot of the commerce between Europe and America. The Irish claim that the glory of discovering this continent belongs to one of their saints, St. Brenden, and that Ireland was the first, as she is now, the most friendly and trusted ally of the great Republic. That no other country, visited by travellers, approaches Ireland in natural attractions, is the belief of every Irishman. Where else do we behold so many great and characteristic features? where such mountains as the magnificent chain of the Connemaras? where gardens so sylvan and lovely, with winding walks, like those in forests, fountains and springs? where lakes like those of Killarney, where savage wihlness ceases to be terrible, because it is inconceivably lovely? where cathedrals and churches of such grandeur and awe-inciting vastness? where such a soil, fruitful enough to support fifteen millions of people? where else can we feel in every air which blows the spirit of health, the freedom (p.4.)

[...] the recent butchery in Manchester, where three young Irishmen were strangled to death, show the desperate fidelity with which the sons of Erin cling to the unconquered purpose of securing independence fur the land of their fathers. Where in the annals of nations do we find such calm and dignified heroism in the very presence of death? The murder of these gallant men has rung the death-knell of English domination in Ireland. From the depths of a million Irish hearts, on this side of the Atlantic, the cry of vengeance has gone forth. There, in the very heart of brutal England, these young heroes, lifted up their dying voices, kept their flags flying and broke forth in electric enthusiasm with the anthem — “God save Ireland!”

[...]

She complains that Elizabeth fomented revolts, murdering a million of the Irish, in order that there might be estates enough for each importunate courtier.

She complains that an English king stole the Earl of Desmond’s estate, six hundred thousand acres — that James the First seized six counties; that eight million acres, two-thirds of the island, were distributed among the supporters of Cromwell.

She complains that William of Orange, he of glorious memory, turned out four thousand families to die upon the road, and then established a penal code worthy of Herod.

She complains that the Second George disfranchised five-sixths of her population, drove a hundred thousand to the army of France.

She complains that her clergy were hunted and massacred.

She complains that seven millions of money, supported by a hundred thousand bayonets, united Ireland to England.

She complains that millions of tithes are wrung from an overworked peasantry to support a miserable set of sporting bishops.

She complains that when the sword failed to exterminate, that England, the Christian nation, the Empire of Hell, organized periodical famines in the years 1817, 1831, 1837, 1847, reducing Ireland from a population of eight millions to half that aggregate.

She complains that the frightful wars of 1641, the revolt of 1798, and the insurrection of 1848 were created by England for the extirpation of the Celtic race.

She complains that confiscation, banishment, and the gibbet, have been used by the Government of England, for the speedy and complete destruction of the Irish people.

She complains that for five hundred years the flower of every generation of Irishmen have been killed on the battle fields, or murdered on the scaffold, or driven into desolate exile for love of Ireland.

She complains that the sacred charter of manhood, without which [9] our life is lower than the dogs, is trampled under the feet of her foreign lords.

Ireland, in the face of Europe, in the face of America, in the face of the great Creator, is amply justified in entering upon a war with England; the people can do so with a free conscience and a full assurance that it is Heaven’s work. It has heen truly and forcibly said, by a powerful writer, that it is no light or factious quarrel. They fight for liberty to live. Hundreds of thousands of Irishmen would again die in the tortures of famine if they continue to bow their necks to the Parliament of England! They fight for liberty to retain the rights of manhood — that in common with every nation in Europe, they may possess arms to defend themselves. They fight to resist outrages more grievous and dishonoring than those for which an English King was brought to the block — outrages which at this hour would cause the swords of France to spring from their scabbords to strike dead their audacious author. They fight because they are denied peace except at the price of dishonor — because their hero leaders are doomed to the prison and to the gallows. They light because the honor, the interest, the happiness, the necessity, the very existence of that ancient nation depends upon the valor of the present time. If the Irish at home cower, flinch, or falter, then the hopes are gone for which their fathers gave their life’s blood. Gone in the stench of dishonor and infamy that will cling to it forever. In God’s name let the struggle begin. Oh! that my words could burn like molten metal through your veins, and light up the ancient heroic daring which would make each Irishman a Leonidas — each battle-field a Marathon — each pass a Thermopylae! (p.9.)[...]

My fellow-countrymen, think of these words of O’Connell, Ireland incarnate. — Think of all that he has said — think of it till your bosom swells, your soul is on fire, your pulses thrill with excitement. Thomas Francis Meagher, the most accomplished and talented Irishman who ever made this country his home, was the first General of the Union army to declare for negro suffrage. He said, speaking of negro soldiers : “ By their fidelity and splendid soldiership, such as at Fort Wagner and Port Hudson, gave to their bayonets an irresistible electricity. The black heroes of the army have not only entitled themselves to liberty, but to citizenship; and the Democrat who would deny them the rights for which their wounds and glorified colors so eloquently plead, is unworthy to participate in the greatness of the nation, whose authority these disfranchised heroes did so much to vindicate.”

Right, brave Meagher!

When Douglas escaped from the grip of slavery, he went to Ireland, landing at Cork. He had a triumphal reception from the city authorities. A magnificent procession was formed, headed by several bands of music, and Douglas, though sitting in a carriage with Father Mathew, was taken out and carried to the banqueting hall on the shoulders of the multitude. A feature of the ovation was a colored boy and an Irish boy chained together, typical of the enslavement of the two races. Love of liberty is inherent in the breast of every Irishman. (p.11.)[...]

The comic preacher of Brooklyn, Ward Beecher, in his recent Thanksgiving Sermon, took occasion to indulge in ironical allusions to the Irish race — calling the European emigrants, particularly the Celts, “a black vomit.”

[...]

Emerson speaks of foreigners as courteously as the Arch bigot of Brooklyn : — “ The Irish and Germans come over here in shoals to dig our canals and manure our fields with their bones, and leave no further trace of themselves.”

Poor Emerson and Beecher! Do they know that Irish intellect, boldness, and industry have contributed many brilliant chapters to the history of the two greatest nations of the earth? (p.12.)[...]

Charles Carroll, of Carrolton, who devoted his princely fortune, and Robert Morris, of Philadelphia, who poured out his wealth like water, to replenish the scanty coffers of the impoverished colonies, were Irishmen. One-third of the revolutionary soldiers who defended New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts from the British hosts, were Irishmen. Chivalrous Montgomery, who fell on the heights of Quebec, with the stars and stripes flying above his head, was an Irishmen. Thomas Addis Emmet, the polished diamond of the New York bar and Attorney- General of the State, was an Irishman. The Pennsylvania legion, whose blood was shed in noble defence of liberty, were Irishmen. Blannerhassett, the man of letters, of music, of philosophy, was an Irishman. Wellington, the great military captain, was an Irishman. The sweetest poet of the English tongue was Moore, an Irishman. Many of the renowned poets, orators and dramatists were Irishmen. The brilliant and powerful dramatic orator, Henry Grattan, whose eloquence was the very music of freedom, was an Irishman. Curran, the eloquent advocate and fearless champion of mankind, was an Irishman. The humorous, witty and patriotic Dean Swift, the most powerful writer of our language, was an Irishman. Edmund Burke, the loftiest name in British annals and a tower of strength to the struggling colonies, was an Irishman. Richard Lalor Sheil, the poet and orator, whose eloquence could even charm the serpents of despotism, was an Irishman. Knox, Thompson, Barry, Paul Jones, McDonough and Jackson, patriots of the past, were of Irish birth and blood. Sheridan, who, according to Byron, wrote the best comedy and pronounced the best oration in the English language, was an Irishman. Sterne, Steele, Usher, Lardner and Goldsmith, the exile from Auburn, “ loveliest village of the plain,” novelists and philosophers, were all Irishmen. Canning, the accomplished diplomatist, who often saved England from ruin, was an Irishman. Hogan and Machlese, great painters, were Irishmen. Generals Napier and Gough, splendid soldiers, are Irishmen. Daniel O’Conneil, mighty in eloquence, and [14] whose commanding majesty of soul embraced within the circle of his sympathies all religions and races, was an Irishman. Meagher, the splendid orator and patriot, whose eloquence even rivalled that of Sheil, was an Irishman. Shields, the shot-proof soldier, the only General who ever gained a victory over Stonewall Jackson, is an Irishman. Charles O’Connor and James T. Brady, the foremost lawyers of the American bar, are Irishmen’s sons. Sheridan, the great military genius of the country, a bulwark in war and a marvel of a soldier, is an Irishman. Mulligan, the gifted soldier, martyr and orator. Conners, the great senator from California, and John A. Logan, the heroic commander of the Army of the Tennessee, honored names and decidedly Irish. [...]

[Devotes some pages to the 1848 Rising and the leaders of Young Ireland; some more pages on Thomas Meagher - the chief focus of the lecture (pp.16-20) who he met in “my native Belfast” (p.16); also Thomas Davis, John Mitchell [sic for Mitchel], John Martin, Mangan, Joseph Brennan, Richard Dalton Williams, Thomas Devin Reilly [”noble conspirator ... a polished gentleman and a brilliant scholar”], John Savage, C. G. Duffy, Michael Doheny, “McManus, Dillon, O’Gormon, O’Doherty, Smythe, Davis the Belfast man, and the charming female poets, Speransa and Eva.”]

Available online; see also under Thomas Devin Reilly [q.v.]

[ top ]

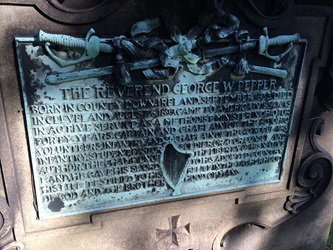

The follow bio-details were posted by Mary Blank Szekely on the Find a Grave website: Born 11 July 1833, Co. Down, N. Ireland; died 6 Aug. 1899 (age 66); son of Nicholas and Rachel (Thornburg) Pepper; m. Christina Lindsey in 1853; f. of six children (George, Samuel Arthur, Charles M., Lena, May, Carrie). The inscription on his grave at Lake View Cemetery, Cleveland, Ohio, reads: “Born in County Down, Ireland, September [sic] 1833. Died in Cleveland August 6, 1889. Came to America in 1854, was in active service as a Methodist minister in Ohio for forty years. Captain and chaplain of the 80 Ohio Infantry and chaplain of the 40 Regulars Infantry. Student, Pastor, Soldier, Orator, Consul and Author, the champion of the liberty of his native country, he gave his sword to his adopted country. His life testified to the belief in the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man.” - . The details in quot\tions marks appear to be his grave inscription - a photo of which is provided by [see online].

Images by Mary Blank Szekely at Find a Grave - online. Click to enlarge.