Life

| 1667: b. 30 Nov. 1667 [‘born in Dublin on St. Andrew’s Day’, acc a TCD MS], 7 Hoey’s Court [then a square of respectable houses, in the Parish of St. Werburgh’s; son of Jonathan Swift, steward at King’s Inn whose his handwriting is preserved in the so-called “Black Book”, and Abigaile Swift [née Erick, b. Wigston Magna, Leicestershire, dg. a butcher; d. 24 April 1710], married by special licence of the Archbishop of Armagh, June 1664), his father dying before his birth (on the supposition that JS Snr. was actually his father); gs. of Thomas Swift (d.1658), vicar of Goodrich in Yorkshire, nr. Ross, dispossessed as Royalist in Civil War; abducted by his (‘over-affectionate’) nurse [in a “bandbox”] and taken to Whitehaven, in Cumbria, where she had relations; later brought back to Ireland - both moves poss. on instructions from Sir John Temple [see note - infra]; after his mother’s return to Leicestershire the young Jonathan Swift [JS] being supported by Godwin Swift, an uncle and Attorney-General of the palatine county of Tipperary; placed by him in Kilkenny Grammar School, 1673, with Congreve, et al., in the year when the Test Act, which excluded Catholics from Parliament and office, was passed by Cavalier Parliament in the wake of the Restoration of 1660; JS entered TCD, 1682; convicted of taking part in college disturbances and obliged to beg pardon of the Dean on bended knee; grad. BA (e speciale gratia) [1686]; |

| 1688: leaves Ireland during the viceroyship of Richard Talbot, Catholic lord-lieutenant in Ireland appt. by James II, and joins his mother his native in Leicester, reuniting after long separation; apparently sent by her to Sir William Temple, then living at Sheen outside London, with a seat at Moor Park, nr. Farnham, 1689; in that household JS meets Esther Johnson (‘Stella’; 1680-1728), then aged 8, being the dg. of a former steward of sir Wm. Temple whose widow was a companion to Temple’s sister Lady Giffard, and poss. the illegitimate dg. of Sir William himself; sent by Temple to Ireland with letter of recommendation to Sir William Southwell, minister of state to William III; fails to secure fellowship at TCD; returns to Moor Hall, acting as secretary to Temple (during 1691-94), and thence to Oxford, where he secures an MA, ad eundum, 1692; wrote Pindaric Odes, 1690-91, one of which, appearing in Athenian Gazette [var. Mercury], provokes Dryden’s remark, ‘Cousin Swift, you will never be a poet’ (acc. Johnson’s Lives); quit Sir William’s household and ordained in Dublin, 1694; obliged to seek Temple’s patronage again to secure living; appointed rector of Kilroot, nr. Belfast, Co. Antrim, with parishes at Ballinure and Templecorran; Jan. 1695; sought marriage with one Jane Waring, dg. of Archdeacon of Dromore (‘Varina’), in the only extant letter of the period; returns to Moor Park and there writes The Battle of the Books, 1696-98; acts as Temple’s literary executor at his death in 1699, and returns to Dublin that year; opposes marriage of his sister Jane (b. April 1666) to one Joseph Fenton, offering her £500 pounds to break it off (acc. to Deane Swift); disappointed in ecclesiastical preferments; appt. chaplain to Earl of Berkeley and to Lord Pembroke, viceroys in Dublin; rectory of Agher, Co. Meath, with united parishes of Laracor and Rathbeggan, to which added prepend of Dunlavin at St. Patrick’s, 1700 (opened 1757), providing income of £230 p.a.; |

| 1701: TCD DD, Feb. 1701 [var. 1702]; appt. prebendary of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, 1701; visits Leicester and London frequently, remaining in London, 1701-04, during which time he formed acquaintance with Pope, Steele, and Addison, et al., thereby associating with the Whig party; ed. Sir William Temple, Miscellanea: The Third Part (1701), incl. sections on popular discontents, health and longevity, ancient and modern learning, and conversation; issues in London a pamphlet Discourses of the Contests and Dissensions between the Nobles and the Commons in Athens and Rome (Sept. 1701), defending Whigs against Tory attack on Partition (or ‘Barrier’) Treaties and dissuasive of impeachment of Lords Somers, Orford, Portland, and Halifax; authorship of same disavowed by Burnet; issues A Tale of a Tub (April or May 1704), a satire on ‘corruption in religion and learning’, in defence of Temple’s Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning (1692), which William Wotton had criticised; receives copy of Addison’s Travels in Italy enscribed “To Jonathan Swift, the most agreeable of companions, the truest friend, and the greatest genius of his age this work is presented by his most humble servant the author”; emissary for the Irish clergy in London, 1707-09, winning wins First Fruits and twentieths, known as ‘Queen Anne’s Bounty’ and prev. granted to the English clergy, for the Irish Church, negotiating with the Godolphin ministry in London, Nov. 1707-May 1709[var. Feb. 1708-April 1709; Sept. 1710]; |

| 1707: first encounters Esther Van Homrigh [vars. Vanhomrigh, Van Homerigh, ‘‘Vanessa’’, b.1690; dg. of Bartholomew Van Homerigh, Dublin Alderman and former Williamite Commissar-General], at an inn in Dubstable en route between Dublin and London, Dec. 1707; later Sherriff of Dublin, MP for Londonderry, and Chief Comm. of Irish Revenue; Lord Mayor of Dublin, 1697; d. 1703, his widow living on till 1715]; issues Baucis and Philemon (Nov. 1707); wrote Story of an Injured Lady Written by Herself, complaining of Ireland’s ‘grief and ill-usage’ by Britain and of suing ‘to be free from the Persecutions of this unreasonable Man, and that he will let me manage my own little fortune to the Best advantage’ (written 1707; suppressed by JS and published in c.1746); in an Answer to the same, he stated principle of Irish independence from all but the Crown; writes An Argument To Prove, That the Abolishing of Christianity in England, May, as Things now Stand, be attended with some Inconveniencies [... &c.] (1708; publ. 1711);Marlborough and Godolphin consolidate with the whigs, and Lord Wharton becomes Viceroy in Ireland, 1708; issues The Sentiments of a Church of England Man with respect to Religion and Government (1708), and A Letter from a Member of the House of Commons in Ireland, Concerning the Sacramental Test (1708), harming him with the Whigs; satirical pieces in Tatler include ‘Bickerstaff Papers’ (from Jan. 1708), in which he ridicules the almanacker John Partridge by predicting his demise [Partridge Papers, 1708-09], spuriously confirming it on 30 March 1709 |

| 1709: issues Vindication of Isaac Bickerstaff, Esq. (April 1709); also the poems ‘Description of a City Shower’ and ‘Description of the Morning’, depicting London life (Tatler, 1709); issues A Project for the Advancement of Religion and the Reformation of Manners (1709); returns to Dublin, June 1709; Queen Anne dismissed the Whig ministers Sunderland and Godolphin in June and August; Queen Anne appoints a Tory ministry led by Robert Harley (1st Earl of Oxford); JS resides in London from Nov. 1710 [var. Sept.]; employed by Harley, with Henry St. John (later Visc. Bolingbroke), 1710-13; writing The Examiner for them, 2 Nov. 1710-July 11; The Conduct of the Allies and Some Remarks on the Barrier Treaty (1711), facilitating the dismissal of the Duke of Marlborough and the creation of 12 new peers; faces antagonism of John Sharp, Bishop of York and Duchess of Somerset - both of whom had influence with Queen Anne and the latter of whom JS has rashly insulted in a lampoon; verse and prose squibs issued as Miscellanies in Prose and Verse (1711), incl. ‘Mrs. Frances Harris’s Petition’ (1709), a burlesque on a servant who has lost her purse; ‘A Meditation upon a Broomstick’ (1710); writes The Virtues of Sid Hamet the Magician’s Rod (1710), a sat. poem attacking Godolphin; The W[in]ds[o]f Prophecy (1711), attacking Duchess of Somerset; A Short Character of T. E. of W [Thomas, Earl of Wharton] (1711), viceroy in Ireland, of dissenter background, and supposed author of “Lilliburlero”, charging him with many crimes and vices; issues The Fable of Midas (1711); also Some Advice Humbly Offered to the Members of the October Club (1712), written against extreme Tories; issues ‘The Prediction of Merlin’, and ‘The History of Vanbrugh’s House’; |

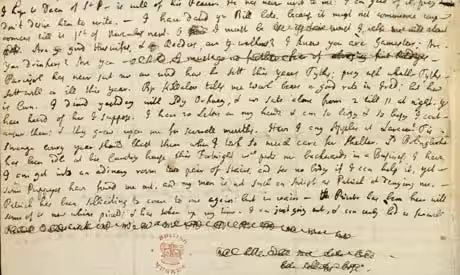

| 1712: writes Journal to Stella (2 Sept. 1710 - 6 June 1713) while in London, being letters addressing Stella and Mrs Dingley [in fact the majority], known as MD, 1st cousin once removed of Sir William Temple, then settled in Ireland; may have been intimate with Vanessa whom he re-encountered as he was living close to her mother’s lodgings, and who appears to have considered herself affianced to him; forms Brothers’ Club (1711-?13), comprising St. John and other ministers, Thomas Prior, Pope, and others, and meeting at St. James’s Palace in the rooms of John Arbuthnot, the Queen’s physician; jointly create “Martinus Scriblerus”, a phantom pedant, whose literary doings incl. the supposed authorship of later works by Pope and Swift incl. Dunciad and Gulliver’s Travels; contrib. to the Tatler, Spectator, and Intelligencer; issues Proposal for Correcting, Improving and Ascertaining the English Tongue (1712); writes History of the Four Last Years of the Queen, 1712-13 (publ. posthum. 1758), which contains his portrait of Robert Harley (later Earl of Oxford); receives admission of love from Stella and alters the character of his communication with her, always being in the presence of Mrs Dingley or another afterwards; |

| 1713: disappointed in not being appointed to vacant Deanery of Wells, Ely and Lichfield, the canonry of Windsor, and the see of Hereford, in spite of plea to Bolingbroke; likewise not appointed to see Raphoe and Dromore in Ireland; finally appointed to St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, with consent of Duke of Ormond who preferred the then Dean to bishopric of Dromore; JS set out for Dublin, June 1713; Journal ends 6th June, at Chester; arrives Dublin circa 8 June; victim of poetical squib by [prob.] John Smedley, Dean of Clogher, nailed to doors of St. Patrick’s (‘Look down, St Patrick, look, we pray [...; &c., as infra]; installed in Deanship, 13 June 1713; retires to his parish at Laracor within a fortnight of his installation (i.e. July); leaves Ireland again, August 1713; issues A Preface to the B****p of S*r*m’s Introduction (1713), an attack on Bishop Burnet [bishop of Sarum/Salisbury]; issues pamphlets incl. The Importance of the Guardian Considered (1713) and Mr C[olli]n’s Discourse on Free Thinking (1713), against Anthony Collins; |

| issues The Publick Spirit of the Whigs (Feb. 1714) in answer to Sir Richard Steele’s Crisis (on the Hanoverian succession), occasioning a pamphlet war that resulted in Steele’s expulsion from the House of Commons, 18 March 1714; returns from Dublin on eve of death of Queen Anne, when the Tories’ apparent indifference to the Protestant succession turned public opinion towards the Whigs, 1714; issues a pamphlet, Some Free Thoughts on the Present State of Affairs, adopting bold plans of Bolingbroke (late Viscount Bolingbroke), incl. utter exclusion of Whigs and dissenters from government, remodelling of army, and restraints on heir to throne (written 1713 but amended by Bolingbroke and then suppressed [var. pub. 1714]); |

| [ top ] |

| 1714: granted £1,000 by Bolingbroke during his 3-day ministry after the expulsion and exile of Oxford, but offers to join Oxford in retirement [var. in prison] and is refused, the news of both events arriving in the same post; receipt of Bolingbroke’s award intercepted by Queen’s death (1 Aug. 1714); lives in seclusion at Upper Letcombe, Berkshire, during final dissension between Oxford and Bolingbroke; Oxford breaks his staff of office, Jan. 1714; death of Queen Anne and return of Marlborough to London with ascent of Hanoverian Elector to the Throne; visited by Vanessa before his departure for Dublin in mid-Aug. 1714 [var. Sept.]; Vanessa follows him to Dublin, Nov. 1714, settling at the family home in Turnstile Abbey, Dublin (which she later sold on advice of Archbishop King), and at Celbridge [at Marlay Abbey; alt. Kildrochid, the name occas. employed in her letters], in his year JS is believed to have privately married Esther Johnson - though they never lived together and only met in company with a third party (Mrs. Dingley); |

| 1720: writes A Proposal for the Universal Use of Irish Manufacture (Dublin 1720), answering the Declaratory Act of that year and stinging the triumphant Whig Administration; gives account of same in letter to Pope (‘a discourse to persuade the wretched people to wear their own manufactures’); prosecution of same by goverrnment dropped; issues The Swearer’s Bank (1720), proposing to start bank for Irish small tradesmen; writes prologue for performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet for the ‘distressed weavers’ of Dublin, 1 April 1721; writes “‘The Description of an Irish Feast” [otherwise “O’Rourke’s Feast”], 1720, a verse translation of ‘Pléaráca na Ruarcach’ written by Hugh MacGauran [anglice Gawran; Gowran], supposedly based on a literal translation provided by the poet [Williams, Poems, Vol. 1, pp.243-44; infra]; writes Letter from Dr Swift to Mr Pope (1722, published 1741); Swift visited Vanessa [van Homerigh] in anger at Celbridge in 1720, prob. in response to a letter sent by her to Stella [Johnson] enquiring if they are married, resulting in a permanent breach between Swift and Vanessa; issues Letter of Advice to a Young Poet (1721); |

1721-23: writes Gulliver’s Travels, 1721-25 - commencing as a “History of my Travels”, at first in character of Martin Scriblerus (letter to Charles Ford, April 1721); Swift undertakes tour of Ireland that brings him to Clogher, Loughgall, et al., in 1722; working on Brobdingnag chapters, June 1722; moves on from “country of Horses” to “the Flying Island” (Jan. 1724); breaks off to enter the controversy over a royal patent awarded to William Wood, an English ironmonger, arranged by Duchess of Kendall, which secured 40% of profit to these two on copper coinage to be minted for Ireland; the death of Vanessa, occurred on 2 June, 1723 - presum. from a broken heart, her will containing a legacy of £3,000 for George Berkeley [see note] but nothing for Swift; Swift destroys all her letters, only one escaping; travels in Leinster, Munster, and Connacht to escape ‘obloquy’, June-Sept 1723; |

| 1724; issues Drapier’s Letters (March 1724-25 Dec 1725), commencing with A Letter to the Tradesmen, Shopkeepers, Farmers, and Common-People in General of the Kingdom of Ireland, by M[arcus] B[rutus], Drapier, published by John Harding in Molesworth Court, off Fishamble St.; asserts that no one is legally bound to accept coin not of gold or silver and computes that those who use ‘those Vile Half-pence ... must lose almost Eleven-Pence in every Shilling’; his “Letter to Mr Harding, the printer” [Letter II] argues that it is honourable to submit to a lion but ‘[what] figure of a man can think with patience of being devoured alive by a rat?’; Committee set up by Walpole engaging Isaac Newton to measure the coinage; Swift’s “Observations on the Report of the Committee” [Letter III] result in a reduction of the bill to £40,000 with limits on the amount of currency citizens were obliged to accept (51d.); this elicited a further letter from Swift in letter to “The Whole People of Ireland” damning the comprise as ‘perfect high treason’, characterising the matter as a battle between ‘one rapacious individual and the whole Irish nation’ [Letter IV]; |

| 4th Letter issued on day that Lord Carteret arrives as Viceroy, sent by Walpole, in Oct. 1724; an offer of £300 for the disclosure of identity of the Drapier posted by Lord Chief Justice Whisgift, for which (as Swift later wrote) ‘no traitor could be found’ - although all of Dublin knew the author; the printer Harding is imprisoned and suffers seriously in his health, but later names his son John Drapier Harding; strenuous pursuit of Swift impeded by the sympathy of Viceroy Lord Carteret, who advises him against declaring himself the author; patent withdrawn and Wood compensated with £3,000 p.a. for 12 years [var. £24,000; prob. modern value]; |

1725-27: Swift preaches a “Sermon on the martyrdom of Charles I, St Patrick’s, [Sun.] 30 Jan. 1725-6” [Hawkesworth, Vol. XI, 1784, p.94]); travels to England with MS of Gulliver’s Travels, March 1726; MS delivered by subterfuge to the printer by Pope and Ford after Swift’s departure for Ireland (‘dropped at his house in the dark from a hackney coach’, acc. Motte), Aug. 172[6]; Motte issues Travels into Several Remote Nations of the Works by Lemuel Gulliver (28 Oct. 1726), and sells 10,000 copies in the first week; even the Duchess of Marlborough willing to forgive Swift; visits London for the last time, with hopes of preferment at the dislodgement of Robert Walpole at death of George I, 1727; dines with Walpole, to whom he addresses a letter remonstrating about Ireland; issues “Letter of Advice to a very Young Lady on her Marriage” (1727); issues A Short View of the State of Ireland (1727), a pamphlet later reprinted as No.15 of the Intelligencer, a weekly paper begun by Swift and his friend Thomas Sheridan in 1729; issued; Miscellanies, 4 vols (1727-1732), jointly with Pope - or rather, issued by Pope with Swift’s best poems while withholding his own (e.g., The Dunciad); |

| 1728: death of Stella, Jan. 1728 (‘I cannot call to mind that I ever heard her make a wrong judgement of persons, books or affairs’); issues A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People from Being a Burden to their Parents or their Country and for Making Them Beneficial to the Publick, pub. Oct. 1729, by Harding’s widow; issued An Examination of certain Abuses, Corruptions and Enormities in the City of Dublin (1732); issued The Grand Question Debated (1729); founds the Intelligencer (1729-30; var. 1728) with Thomas Sheridan, giving ‘two or three of us a chance to indulge our fancy by writing a personal commentary’, acc. Swift himself; receives Freedom of City of Dublin, 1729 for the Drapier’s Letters; issues Traulus (1630), attacking Lord Allen; writes Directions to Servants (c.1731; publ. 1745); writes A Complete Collection of Polite and Ingenious Conversation (1731; publ. 1738); writes “Hamilton’s Bawn”, a poem; writes Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift (composed 1731; publ. 1739 - incompletely in London and correctly in Dublin); issues The Day of Judgement (1731); writes A Letter to a Young Gentleman lately entered into Holy Orders (1731); raises a black marble slab in memory of the Duke of Schomberg who is buried beneath the altar of the Cathedral, inscribed with his own Latin inscription naming the English descendents of the Duke who were unwilling to fund a monument, 1731; |

| 1732 issues The Lady’s Dressing-Room (1732) and The Beasts Confession to the Priest (1732), on ‘universal folly of mankind in mistaking their talents’; issues A Serious and Useful Scheme to make an Hospital for Incurables, whether the Incurable Disease were Knavery, Folly, Lying, or Infidelity (1733); writes An Epistle to a Lady (1733) and On Poetry: A Rhapsody (1733), containing satirical advice; also writes A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed [1734]; Strephon and Chloe (1734); The Legion Club (1736), on the Irish Parliament, and regarded as his fiercest verse satire; first edition of his Works printed by George Faulkner (1735), including a ‘prefatory letter’ added to Gulliver’s Travels’; issues imitations of 7th Epistle in Book I and First Ode of Book II of Horace (1738); suffers increasing attacks of giddiness, now known to be Menière’s disease and so diagnosed by Dr. J. C. Bucknill in 1882; makes his will, ‘being of unsound mind and memory’, Aug. 1939; having spent a third of his wealth on Irish charities, he bequeathes another third to establish St. Patrick’s Hospital for Imbeciles (opened 1757) with a bequest of £11,000; the will includes his epitaph, to be inscribed on black marble ‘large letters, deeply cut and strongly gilded’; |

| 1742: declared of unsound mind and body [var. mad, insane] by committee of 19 in 1742, ‘a shocking object, though in person a very venerable figure’ (acc. Mary Delaney); exhibited by his manservant Patrick Brell; four sermons by Swift appeared in 1744; saw little of Delany and indulged Francis Wilson, rector of Clondalkin, as a friend and was prob. cheated out of of tithes and books from his library by him; JS d. 19 Oct. 1745 (aetat. 78); bur. at night, beside Stella, 22 Oct. at foot of 2nd column from west end, south side of St. Patrick’s Cathedral; his epitaph written by himself (ubi saeva indignation ulterius cor lacerare nequit) appears on an oval plaque set in the wall; William Stopford, later Bishop of Cloyne, acted as one of his executors; an autobiographical fragment in Swift"s hand was donated to Trinity College Library by Deane Swift, his great-nephew and biographer, on 23 July 1753; the contents of his library were catalogued by William Le Fanu in 1745; there are portraits of Swift by Jervas and Francis Bindon (with a carved oak frame by John Houghton), and a marble bust by Louis-Francois Roubillion in the TCD Library Long Room; commemorative services are held annually at the St. Patrick’s Cathedral on the anniversary of his death. RR CAB ODNB JMC PI DIB DIW DIL OCEL ODQ FDA OCIL |

| [ top ] |

Works

[See separate file - infra.]

Criticism

[See separate file - infra.]

Commentary

[See separate file - infra.]

|

Dictionary of National Biography: The article on Swift is by Sir Leslie Stephen, the founding-editor of same and author of a monograph on Swift in the English Men of Letters Series (1822, & edns.)

Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies, Vol.II [of 2] (London & Dublin 1821), pp.578-89.

[...]

In his poem of “Cadenas and Vanessa,” Swift had published to the world what may be termed the story of their loves; but with base and unmanly cruelty, had affected to veil its termination in a mystery, which was fatal to the reputation of his enamorata [sic]. Deserted by the world, and piqued at the coolness of Swift, who, however, visited her frequently, but answered her proposals of marriage merely by turns of wit, she at length became unable to sustain any longer her load of misery. She wrote to him a very tender letter, insisting upon a serious answer; an acceptance, or a refusal. His reply was delivered by his own hand. Throwing down the letter on her table with great passion, he hastened back to his house. From his appearance she guessed at the contents of his letter; she found herself entirely discarded from his friendship and conversation; her offers were treated with insolence and disdain; she met with reproaches instead of love, with tyranny instead of affection. She did not many days survive it; she testified her disgust and disappointment by cancelling the will she had made in his favour, and expired in all the agonies of despair.

It has been conjectured, that in this letter, Swift revealed [585] to her the secret of his marriage with Stella, which was privately solemnized in 1716. With qualities almost entirely the reverse of those of Vanessa; mild, humane, polite, and pious, amiable both in mind and in person, and possessed of almost every accomplishment, her fate was little different. Whatever were his motives to this marriage, Swift continued to live with her on precisely the same terms as he had previously. Mrs. Dingly [sic for Dingley] was still her inseparable companion, and it would be difficult to prove that Swift and Stella ever conversed alone. She never resided at the deanery, except during his fits of giddiness and deafness, and on his recovery she always returned to her lodgings, which were on the opposite side of the Liffey. A woman of her delicacy must repine at so extraordinary a situation. Absolutely virtuous, she was compelled by her husband, who scorned even to be married like any other man, to submit to all the outward appearances of vice. Inward anxiety affected by degrees the calmness of her mind and the strength of her body. She began to decline in her health in 1724, and from the first symptoms of decay, she rather hastened than shrunk back in the descent; tacitly pleased to find her footsteps tending to that place where they neither marry nor are given in marriage. It is said, that Swift did at length consent that she should be publicly acknowledged as his wife; but the core had rankled too deeply, her health had departed, and she exclaimed, “it is too late.” She died in January 1727, absolutely a victim to the peculiarity of her fate; a fate which she merited not, and which she probably could not have incurred in an union with any other person. “Why the dean did not sooner marry this most excellent person,” says the writer of his life; why he married her at all; why his marriage was so cautiously concealed; and why he was never known to meet her but in the presence of a third person; are inquiries which no man can answer without absurdity.”

The character which Swift had acquired as a man of humour and wit, had in a great measure removed that odium [586] which his politics had attached to him, when the appearance of his “Proposal for the Use of Irish Manufactures,” elevated him immediately into a patriot. Some little pieces of poetry to the same purpose, were no less acceptable and engaging, and he soon became a favourite of the people. His patriotism was as manifest as his wit, so peculiarly captivating to the natives of Ireland; he was pointed out with pleasure and respect as he passed along the streets: but the popular affection did not rise to its height till the publication in 1724, of the “Drapier’s Letters,” those “braaen monuments” of his fame. A patent had been obtained by a person of the name of Wood, for the copper coinage, which was executed so badly and so low in value, as to become the general subject of complaint. In these letters, in a series of inimitable wit, and irresistible argument, the whole nation was advised to reject the base coin. The advice was followed; Wood decamped with his patent; the government was irritated to the extreme; and a large reward was offered by proclamation for the author of the letters.

[...]

See Ryan, Biog Hibernica, Vol. II (1821), “Jonathan Swift” - via index; or as attached.

Encyclopaedia Britannica (1949): ‘[Sir William] Temple had in 1692 published his Essay upon Ancient and Modern Learning, transplanting to England a controversy begun in France by Fontenelle ... Temple had cited the letters of Phalaris as evidence of the superiority of the ancients over the moderns. William Wotton’s criticism of Temple’s general conclusions caused Swift to write Battle of the Books in 1697 in refutation. Boyle’s Vindication and Bentley’s refutation of the authenticity of Phalaris came later. Swift’s aim was limited to co-operation in what was then deemed the well-deserved putting-down of Bentley by Boyle, with a view to which he represented Bentley and Wotton as the representatives of modern pedantry, transfixed by Boyle in a suit of armour given him by the gods as the representative of the ‘two noblest of things, sweetness and light’. Though written in 1697, the satire remained unpublished until 1704, when it was issued with The Tale of a Tub. See also the account of Swift’s relationships with Stella (b. March 1680) and Vanessa (b. 14 Feb. 1690). Swift offered no obstacle to proposed marriage of Stella to Dr William Tisdall of Dublin; met in London Esther Vanhomrigh (b. 14 Feb. 1690), dg. of Dublin merchant of Dutch origin, Swift then lodging close to her mother; Swift wrote “Cadenus and Vanessa”, prob. in 1713; Vanessa followed Swift to Ireland at death of her mother, 1714, settling at Marley House in Celbridge, nr. Dublin; to persuade her of the hopelessness of her passion [but note that the date of his first encounter with Vanessa is put at 1707 in Dunstable by Sybil Le Brocquy]. E.B. article continues ‘Swift was devoid of passion; of friendship, even tender regard, he was fully capable, but not of love, and Vanessa’s ardent and unreasoning display of passion was beyond his comprehension; yet [she] assailed him on a very weak side; the strongest of his instincts was the thirst for imperious domination; Vanessa hugged the fetters to which Stella merely submitted ...; unable to marry Stella without destroying Vanessa, or openly to welcome Vanessa without destroying Stella, he ... continued to temporise; had the solution of marriage been open Stella would undoubtedly have been his choice; but some mysterious obstacle intervened’. In 1723 Vanessa wrote to Stella seeking to know the nature of her relations with Swift; Stella sends the letter on to Swift; Swift storms out to Celbridge with same; Vanessa died within weeks; left the correspondence (viz, Cadenus) for publication; later edited by Walter Scott’ [Cf. Oxford Companion to Irish Literature: only when Vanessa died did Swift circulate the manuscript.]

Seamus Deane, ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 1 selects passages from Gulliver’s Travels; A Tale of A Tub; A Modest Proposal; A Proposal for the Universal Use of Irish Manufacture; The Journal to Stella; Verses on the Death of Dr Swift; The first Drapier’s Letter; Letter to Alexander Pope; ‘The Description of an Irish-Feast’; ‘Epigram[s]’; ‘an Epilogue, to be spoken at the Theatre-Royal; ‘A Character, Panegyric, and Description of the Legion Club’; ‘The Blessing of a Country Life’; ‘The Plagues of a Country Life’; ‘Holyhead’; ‘In Sickness’; ‘A Pastoral dialogue’; ‘Verses said to be written on the Union’; ‘Part of the 9th Ode of the 4th Book of Horace’; ‘A Serious Poem upon William Wood’; ‘Horace, Book 1, Ode XIV’; ‘Ireland’ [‘Remove me from this land of slaves / Where all are fools, and all are knaves / Where every fool and knave is bought / Yet kindly sells himself for nought ..’]; Letter to the Earl of Peterborough; Two Letters to Charles Wogan [see extract under Wogan, q.v.]. Bibl.: Carpenter’s biographical and critical notice (FDA Col. 1, p.327), cites Carole Fabricant, Swift’s Landscape (Johns Hopkins UP 1982); Frank Lloyd Harrison, ‘Music, Poetry and Polity in the Age of Swift’, in Eighteenth-Century Ireland, I (1986), pp.37-83; Alan Bliss, ed., A Dialogue in Hybernian Style and Irish Eloquence, by Jonathan Swift (Dublin Cadenus Press 1977); Carpenter & Alan Harrison, ‘Swift’s “O’Rourke’s Feast” and Sheridan’s “Letter”’, in Proceedings of the First Munster Symposium on Jonathan Swift, ed. Hermann J. Real and Heinz J. Vienken (Munich: Fink 1985). See also FDA - Gen. Bibl.: Herman J. Real & Heinz J. Vienken, eds., Proceedings of the First Münster Symposium on Jonathan Swift (Munich: Wilhelm Fink 1985) [incl. Andrew Carpenter & Alan Harrison, ‘Swift’s “O’Rourke’s Feast”’ and Anthony Raymond, Sheridan’s “Letter”, Early transcripts’; Clive T. Probyn & Bryan Coleborne, eds., Monash Swift Papers, I (1988) [incls. Bryan Coleborne, ‘Jonathan Swift and the Voices of Irish Protest against Wood’s Halfpence’, pp.66-86]; Coleborne, ‘Jonathan Swift and the Literary World of Dublin’, Englisch Amerikanische Studien, I (1988), pp.6-28; Coleborne, ‘Jonathan Swift and the Dunces of Dublin’, unpublished Ph.D. thesis, NUI 1982; Oliver W. Ferguson, Jonathan Swift and Ireland (Illinois UP 1962); also J. M. Treadwell, ‘Swift, William Wood, the Factual Business of Satire’, the Journal of British Studies, 15, 2 (Spring 1976), pp.76-91; Treadwell, William Wood and the Company of Ironmasters of Great Britain’, in Business History 16 No 2 (July 1974), pp.97-112. Note the reference to Swift’s ‘O’Rourke’s Feast’ in Oliver Goldsmith’s anonymous ‘Description of the manners and customs of the native Irish’ (1759) [see under Goldsmith]: ‘A song beginning O’Rourke’s noble fare will ne’er be forgot’, translated by Dean Swift, is of his [Carolan’s] composition, which though perhaps by this means the best known of his pieces, is yet by no means the most deserving. His songs, in general, may be compared to those of Pindar, as they have frequenty the same flights of imagination, and are composed (I don’t say written ..) merely to flatter some man of fortune … .’ Deane adds a footnote: ‘The Description of an Irish-Feast’, translated almost literally out of the original Irish, pub. by Swift in 1735 (H. Williams, ed, Poems, 1937, pp.243-47), actually from ‘Pléaráca na Ruarcach’ of Aod mac Gabhráin [Hugh MacGauran]. Further, When the Union of England and Scotland was effected in 1707, Swift, who strongly opposed it, reminded his audience of the inherently unstable order in Ireland, and when it was planned to establish a bank in Dublin in 1720, [Bryan Coleborne, ed., 474; see further under William King, q.v.]

Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (1953 & edns.) contains 115 items from his writings. Arthur Ponsonby, Scottish and Irish Diaries [ …] &c (London: Methuen 1927) contains extracts from Journal to Stella.

John Montague, ed., The New Book of Irish Verse (OUP 1986), selects “On Stella’s Birthday”; “The Description of an Irish Feast”; “The Progress of Poetry”; “Clever Tom Clinch Going to be Hanged”; “Holyhead, Sept. 25, 1727”; also extract from The Life and Character of Dean Swift, and from Verses on the Death of Swift.

W. J. McCormack, ed., Ferocious Humanism: A Critical Anthology of Irish Poetry from Swift to Yeats (London: J. M. Dent 1998) incls. selection.

[ top ]

A. N. Jeffares & Peter Van de Kamp, eds., Irish Literature: The Eighteenth Century - An Annotated Anthology (Dublin/Oregon: Irish Academic Press 2006), lists The Humble Petition of Frances Harris [28]; From A Tale of a Tub [The History of Christianity] [31]; “A Description of a City Shower” [39]; From The Journal to Stella [41]; “Stella’s Birthday” [43]; A Modest Proposal [45]; “The Description of an Irish Feast” [52]; A Pastoral Dialogue [55]; From Gulliver’s Travels: Gulliver’s arrival in Lilliput [57]; Gulliver praises England to the King of Brobdingnag [62]; Gulliver learns of the Struldbruggs [65]; Gulliver visits the Houyhnhnms [72]; Gulliver’s return to his home [76]; “An Epigram on Scolding” [77]; “Verses Made for the Women Who Cry Apples, &c.” [77]; Early Disappointments Recollected by Swift [79]; From Swift’s Letter to Charles Ford (12 November 1708) [79]; From Thomas Sheridan, The Life of the Rev. Dr Jonathan Swift (1784) [79]; From Swift’s Letter to Viscount Bolingbroke and Alexander Pope (5 April 1729) [79]; Verses on the Death of Dr Swift, D.S.P.D. [80]. Also Swift and Sheridan, extracts from The Intelligencer, incl. Intell., 2 (1729) [‘Occusare capro, cornu ferit ille, caveto [take care not to meet a he-goat, he butts with his horn’, being an allusion to Abem Ram, a tyrannical and uncharitable landlord from Gorey, Co. Wexford, whose coachman drove at the authors while walking there]; Intell., 13 (1729) [‘Sermo datur cunctis, animi sapientia paucis / The art of converation is given to all, but a wise spirit to few’ - dealing with the art of Story-telling, and its types, short-story teller, long Story-teller, marvellous, the insipid, the delightful story-teller];

Library of Herbert Bell (Belfast), holds Gerald P. Moriarty[?], Dean Swift and His Writings (London 1893). BELF [1958] holds 15 titles, among which these early editions, Tale of A Tub (1711); Schemes from Ireland (1732);

Emerald Isle Books (Cat. 95) lists John Boyle [Earl of Orrery], Remarks on the Life and Writings of Jonathan Swift in a series of letters to his son the Hon. Hamilton Boyle (Dublin: Faulkner 1752), port of Swift. [£85.]

Hyland Books (Cat. 224; Dec. 1995) lists The Works of Dr Jonathan Swift, Dean of St Patrick’s, Dublin 1760-7 [Teerink 90]; 20 vols. [missing 6, 13, £180]; Le Procès sans Fin, ou l’Histoire de John Bull ... par le Docteur Swift; A Londres, chez J Nours (1753), xxiv+248pp [attrib. to Arbutnot in Teeerink]; Laurence Sterne, A Sentimental Journey and Swift, A Tale of a Tub (Nimmo & Bain 1882) [ltd. edn. 150], ills.; Joseph Horrell, Collected Poems of Jonathan Swift, 2 vols. (1958), lxvi+vi+818pp.; Louis A Landa, Swift and the Church of Ireland (1954); Ricardo Quintana, Swift, An Introduction (1955); James E Preu, The Dean & the Anarchist (Tallahassee 1959) [Swift’s influence on Godwin]; Harold Williams, the Text of Gulliver’s Travels [Sanders Lecture on Bibliography, 1950] (1952) [ltd. edn. 500] [Hyland 214]. The Works of Jonathan Swift, DD, 23 vols. large octavo [Teericnk 88A] 1754-1775 [lacking 2 suppl. vols. published in 1776 and 1779]; incl. 6 vols of letters bound as vols. 17-22, and vol. 17 of Works bound as vol. 23: all £650; George Hill, Unpublished Letetrs of Dean Swift (199); Elizabeth Malcolm, Swift’s Hospital: A History of St Patrick’s Hospital, Dublin 1746-1989 (1989); Irven Ehrenpreis, Swift: The Man, His works and His Age, Vol. II Dr. Swift [1st edn.] (1967); Herbert Davis, Stella: A Gentlewoman of the Eighteenth Century (NY: 1942); J. M. Murry, Swift (1961), port, 43pp. [Hyland, 224, Dec. 1995].

Peter Harrington Books (Cat. 2005) lists Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts by Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships. London, Printed for Benj. Motte, 1726 [£35,000], 2 vols. 8o., finely bound in recent period style full red morocco, with full decoration to spines gild, raised band, decorative borders to boards gilt, inner dentelles gild, marbled endpapers; houses in red buckram slip case; frontis. port; 4 maps and 2 plans; page stock tpically a little browned but untypically in pure original condition - never washed or pressed the volumes bulk every bit as thick as when published; v. uncommon thus. First Edition. Teerink “A” edition with four necessary points: Part I, p.25, line 5 has “Subsidies” correctly spelled; Part III, p.74 is misnumbered “44”; Part III, G6 is a cancel, with “Part III” at foot; Part IV, p.52, line 1 has the misprint “buth is”. Also, ont he special title to Part IV the word “Voyage” is printed with capitals. With the portrait of Gulliver in state “B” (as usual. The first of three editions dated 1726 (the subseq. edns. being Teerink AA and B). The first five editions of Gulliver’s Travels, three octavo editions in 1726, one octavo and one 12mo edn. in 1727, were all published by Benjamin Motte. The first Issue of Gulliver[’s] Travels is one of the rarest and most desireable books in the English language. It was noted by John Gay that, “the whole impression sold in a week.” It was hailed as a classic that “would last as long as the language, because it described the combination of qualities which made it at once a favourite book of children and a summary of bitter scorn for mankind” (DNB.) “Gulliver’s Travels has given Swift immortality beyond temporary fame.” (PMM 185.) [£35,000.]

[ top ]

COPAC lists over 4,600 items. [online; accessed 8.7.2020].

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Belfast Public Library [Add. Catalogue to 1993] holds Sir Harold [Herbert] Williams, ed., Jonathan Swift, Journal to Stella (Oxford: Clarendon 1948), 2 vols. University of Ulster Library (Morris Collection) holds Works (1814) [incomplete set].

British Library [search terms: ‘Swift/St Patrick’] yields W. H. Dilworth, The Life of Dr. Jonathan Swift, Dean of Saint Patrick’s, Dublin. [Another edition]. pp.iv. 139. G. Wright: London, 1758. 12o […] pp.iv. 137. H. Woodgate; S. Brooks: London, 1760. 12o; A Poem upon R[ove]r, a Lady’s spaniel. [By Jonathan Swift, Dean of Saint Patrick’s, in ridicule of Ambrose Philips’ poem on Miss Carteret.] MS. note [...] [Dublin? 1725?] s. sh. fol.; Saint Patrick’s Purgatory: or, Dr S---t’s [Swift’s] expostulation with his destressed friends in the Tower and elsewhere. Shewing the true reasons why he withdrew himself to Ireland upon a certain occasion; and discovering all that happened to him thereupon. Dedicated to the E--- of Ox-d. With a poetical description of the frozen river of Thames. [dedication is signed J. S., i.e. Jonathan Swift]. pp.26. R. Burleigh: London, 1716. 8o.; The Beasts Confession to the Priest, on observing how most men mistake their own talents. [In verse.] By J. S., D.S.P. [i.e. Jonathan Swift, Dean of Saint Patrick’s]. London, 1738. 8o.

[ top ]

| Abigail Williams, ed., Journal to Stella (Clarendon Press 2013) |

|

| See Maev Kennedy, on the forth-coming OUP edition of Journal to Stella edited by Abigail Williams, in Guardian, 28 Jan. 2011 [infra]. |

Maev Kennedy, review of Journal to Stella, ed. Abigail Williams, in Guardian, 28 Jan. 2011: The edition -which later appeared in 2013 - includes 65 letters and Williams examined 25 surviving manuscripts in the British Library to crack Swift’s code involved crossing-outs and the well-known infantile phrases (viz., ‘poo poo ppt’) which James Joyce imitated, or perhaps parodied, in Finnegans Wake (1939) in applying Swift’s affectionate term “Pipette” to the young Issy in his experimental novel. Williams’ edition appeared in 2013. Kennedy writes: ‘The baby talk passages are in tiny writing and often lightly crossed out. Scholars assumed this was done after Swift’s death to protect the reputationof the author of Gulliver’s Travels. But Abigail Williams, an English tutor at St Peter’s College, Oxford University, who edited the letters, is convinced he crossed out his own words.’ - quoting Williams: ‘I think the effect was intended to be a kind of guessing game with his readers. The women he was writing to needed to undress the text before they could fully enjoy it. This disguising of affectionate endearments is clearly part of a secret code of intimacy that characterises the journal as a whole, which uses baby language and a series of special names to emphasise the closeness between Swift and his readers. / The interesting thing is he doesn't cross out quite sensitive political or court gossip, or the bawdier passages – it’s just the baby talk, which is both infantilising and quite sexualised. The effect is to create a special place – not necessarily a place one would want to go to.’ Kennedy also cites Swift’s sentence, ‘ ‘tis still terribly cold - I wish my cold hand was in the warmest place about you, young women.’ (Available online; accessed 26.01.2024.)

| ‘Sweetness and light’: Matthew Arnold’s tag for Hellenism in Culture and Anarchy comes from Swift’s Battle of the Books. |

Modest Proposal: Richard Dickson, the bookseller who sold The Modest Proposal, gave a notice of it in his news-sheet Dublin Intelligence (Sat. 8 Nov. 1729), as follows: ‘The late apparent Spirit of Patriotism, or Love to Our Country, so abounding of Late, has produced a New Scheme, said in Publick to be written by D--- S----, wherein the Author as an Effectual Means for preventing the Children of Poor People, from being a Burthen to their Parents or Country, and for making them Beneficial to the Public, and save Expences to the Nation, ingenuously Advises that one Fourth Part of the infants under Two Years Old, be forthwith Fatten’d, brought to market and Sold for Food, reasoning that they will be Dainty Bits for Land Lords, who as they have already Devoured most of the Parents, seem to have the best Right to Eat up the Children. N.B. This Excellent Treatise may be had at the Printers hereof.’ (Quoted in James Ward, ‘Bodies of Sale: Marketing a Modest Proposal’, in Irish Studies Review, August 2007, pp.284-85, as supra.)

Ward remarks, ‘By paraphrasing its giveaway line […] Dickson’s advertisement spoils any claim that the Proposal might have over all but the most obtuse reader’s credibility’ - and further notes that by being offered for sale among specifics for common diseases of the day, ‘Swift’s text become complicit in the processes it would indict.’ (Ibid., p.285.)

Drapier’s Letters: The 1st Letter argues for the sovereign rights of kingdom of Ireland in terms derived from William Molyneux (‘by the laws of God, of nations, and of your own country, you are and ought to be as free a people as your brethren in England’; McMinn, ed., Irish Pamphlets, 1991, p.80); 2nd Letter assails Wood and the Duchess of Kendal (How dare he oppose a nation [... / ...] how can he hope to oppose a nation?’); 3rd Letter addresses the nobility and gentry and asserts right of Ireland to autonomy as of equal status with England under the crown; 4th Letter launches invective against slavery, tyranny, injustice, addressing this time ‘the Whole People of Ireland’; 5th Letter addressed to Robert Molesworth, adopts a calm and reasonable tone, the patent having been by this date withdrawn.

Letter to Langford: W.E.H. Lecky writes: ‘There is a curious lettter of Swift extant, to Sir Arthur Langford, rebuking him for allowing a [Presbyterian] conventicle to be built on his property, and threatening to take measures to shut it up.’ (Letter of 30 Oct. 1714; Swift’s Correspondence, ed. 1766, ii, 19-21; Lecky, A History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century [Cabinet Edn. 1892; 1913 iss., p.427n2.)

Travelogues: Swift read works such as Hakluyt’s Voyages (1587), Linshcoten’s Voyages into the Easte and West Indies (1598), and William Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World [3rd edn.] (1698-1703 as well as Gabriel de Foigny’s La terre australe connue (1676). See Peter Kuch, ed. & intro., Irelands in the Asia-Pacific , Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 2003, p.x. And further: ‘It is open to speculatioin whether Dampier’s supposedly first-hand account of the Australian aboriginals as “the most miserable people on earth” provided Swift with his favourite epithet for the Yahoos, there is no doubting the longevity of the image, for two centuries after this description was first published […] it was still being reproduced in Australian school-texts, with baleful effects […].’ (Ibid., p.xi.)

Daniel Defoe (1660-1731): Robert Harley (1st Earl of Oxford), the Tory chief whom Queen Anne appointed as Prime Minister on her accession the throne, employed Defoe as a spy, counsellor and pamphleteer during 11 years following the publication of his Legion’s Memorial. In Feb. 1704, Defoe launched The Review. By 1715, he had turned from politics to fiction though during that time he had issued History of the Union (1707), composed in Scotland with the aim of supporting the Government’s plan, building on the conception of the British as a non-regional people which had characterised The True-Born Englishman (1701) - a satire on those who attacked William III for his Dutch origins, and which rendered Defoe attractive to the whigs behind William and the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Defoe’s pamphlet The Shortest Way with Dissenters (1702) was a satirical essay on the theme of anti-Presbyterian sentiments in the triumphalist Anglicanism which was sounded at the time of Queen Anne’s accession. It cost him a time in the stocks though he was defended by a honour guad of supporters and won general popularity by his writings. His Hymn to the Pillory (1703) marks this experience. His subsequent works incl. The Family Instructor (1715), A Diary of the Year of the Plague (1722), A Tour of the Island of Great Britain (

[ top ]

Duke of Schomberg: Swift wrote to Lady Holderness, a descendent of the Duke of Schomberg, inviting her to contribute to the cost of a memorial for the Duke, who had died at the Battle of the Boyne, and was ignored. In 1831 he set a black marble plaque in the cathedral with his own inscription which includes the information that the descendants had been unwilling to assist: [...] Decanus et capitulum maximopere etiam atque etiam petierunt, ut haeredes Ducis monumentum in memoriam parentis erigendum curarent. / Sed postquam per epistolas, per amicos, diu ac saepe orando nil perfecere; hunc demum lapidem statuerent; saltem us scias hospes ubinam terrarum SCHONBERGENSIS cineres delitescunt.

See J. Crofton Croker, Historical Songs of Ireland, Percy Society 1841, p.68ff. Croker quotes a longer and mores stinging version of the inscription which he finds in Dr. Delany’s memoir. The whole transaction is quoted from william Monck Mason’s History of the Antiquities of the Church of St Patrick (1819).

Stella (Esther Johnson): Swift included a collection of her witticisms was published under the titles on Bon Mots de Stella as an appendix to some editions of Gulliver’s Travels. A portrait of ‘Stella’ appeared in Faulkner’s edn. of Swift’s Works (Dublin 1768). The original hangs above the mantelpiece of the Irish Consulate in Washington, DC, on loan from the National Gallery of Ireland [in 2008]. ‘Stella’ is also the name of one of the wards at St. Patrick’s hospital, Dublin. There is a novel on the Stella-Swift relationship (Trudy J. Morgan-Cole, The Violent Friendship of Esther Johnson, Canada: Penguin 2006).

Patrick Delany tells the story of Archbishop King, saying after Swift had just rushed from the room in tears, ‘You have just met the most unhappy man on earth; but on the subject of his wretchedness you must never ask questions’ (copied by Scott and Thackeray).

Swift’s library: The contents were compiled by William Le Fanu in ‘A Catalogue of Books belonging to Dr. Jonathan Swift, Dean of St Patrick’s, 19 Dec. 1745.’

Marsh’s Library copy Clarendon’s The History of the rebellion and civil wars in England, begun in the year 1641, 3 vols. (Oxford: at the Theater 1707, 1703, 1704) holds extensive annotations by Jonathan Swift virulently antagonistic to the part played by the Scots, along with marginal corrections of Clarendon’s prose, especially repetitions of words within a short space, which Swift calls cacofonia.]

James Joyce - echoes Swift in Finnegans Wake (1939): Behove this sound of Irish sense. Really? / Here English may be seen. Royally? / One sovereign punned to petery pence. Regally? / The silence speaks the scene. Fake!’ [FW], a parody of Swift on the magazine fort. Cited in Atherton, Books at the Wake, p. 121. Swift is a pervasive figure in the Wake colouring many phrases, viz., ‘Gaping Gill, swift to mate errthors, stern to checkself [... &c.]’ (FW 037). Further, in Finnegans Wake, Joyce copies Swift’s letter to Vanessa (Esther van Homerigh) on her birthday - St. Valentine’s Day: ‘[accept this torn letter] of a linenhall valentino with my fondest and much left to tutor. X.X.X.X.’ [FW 458.02] See A. Martin Freeman, Vanessa and Her Correspondence with Jonathan Swift, London 1921), p.11ff.

Modest proposal (cannibalism): There is a biblical precedent for the theme of A Modest Proposal: ‘And I will cause them to eat the flesh of theirs sons and the flesh of their daughters.’ (Jeremiah, 19, 9.)

Francis Doherty discusses the impact on Samuel Beckett of biographies of Swift by Stephen Gwynn (Life and Friendships of Dean Swift [London: Thornton Butterworth] 1933) and Mario Rossi & Joseph M. Hone (Swift, or The Egotist, London 1934) in ‘Watt in an Irish Frame’, Irish University Review (Autumn 1990), pp.191ff.

[ top ]

Moor Park, the home of Sir William Temple, whom Swift served as secretary, and were he taught Esther Johnston (‘Stella’), was later used as a lunatic asylum, a college of theology, a home or code-breaking unit in World War Two, and a centre for the study of primates; now attached to the University of Surrey. (See review of Moor Park, the 1994 novel by Gabriel Josipovici, in Times Literary Supplement, 23 Sept. 1994.)

Brinsley MacNamara, “On Seeing Swift at Laracor” [poem], deals with his servant Patrick Brell, who ‘sold him for a show’. [i.e., during his mental decline].

Lost letter: A ‘Lost’ satirical letter by Swift was in the keeping of Mrs. Aldworth of Co. Cork, acc. to Arthur Young (A Tour of Ireland, 1780; see under Young, infra.)

John Jordan, in Patrician Stations (1971), writes of St. Patrick’s Hospital, Dublin’s Mental Asylum particularly dedicated to alcoholic retreats: ‘Your Toms, Dicks and Harrys are here, great Dean. / You gave your lolly to found our first democratic / institution. Paudeen and Algernon rub minds.’

Edmund Burke compares the French Assembly with the floating island in Gulliver’s Travels, ‘From its general aspect one would conclude that it had been for some time past under the special direction of the learned academicians of Laputa and Balbibarbi’ (Reflections, ed. Conor Cruise O’Brien, p.238).

George Faulkner had a bust of Swift, commissioned from Patrick Cunningham, installed outside his shop, 1763, an engraving of same being used for the 14 vols. duodecimo edn. of the works (1768); the bust was later presented to St. Patrick’s Cathedral and placed in a niche there in 1776. (See Robert Mahony, Jonathan Swift: The Irish Identity (Yale UP 1995).

Alexander Pope addresses the opening lines of The Dunciad to ‘Dean, Drapier, Bickerstaff or Gulliver’ and compares him to Cervantes and to Rabelais (‘Rab’lais’).

Sean O’Casey includes Swift among the the symbolic population of his heroic Dublin in Red Roses for Me (Act. III): Rector, ‘I’ve read that tens of toughs such as those [whom Inspector has called ‘flotsam and jetsam’] followed Swift to the grave.’ Inspector, ‘Indeed, sir? A queer man, the poor demented Dean; a right queer man.’ (Three More Plays, Pan Edn. 1978, p.279).

Fr. Prout (Francis Sylvester Mahoney) provides himself with Swift for a father and Stella for a mother in his character as Fr. Prout of Watergrasshill, in ‘Dean Swift’s madness, or the Tale of a Churn’, also defends Swift agains charges of barefaced political opportunism in claiming that he ‘sought not the smiles of court, nor ever sighed for ecclesiastical dignities’. (Cited in Terry Eagleton, ‘Cork and the Carnivalesque: Frances Sylvester Mahony (Fr. Prout)’, in Irish Studies Review (Autumn 1996), pp.2-7; p.2.

Journal to Stella: The original letters of the Journal to Stella were offered for sale at Sotheby’s and bought by the British Museum in May 1919, as part of the Morrison collection; they were bound as a volume in fine calf with the inscription, ‘Original Letters of Dr Jonathan Swift, Dean of St. Patrick’s, Dublin, to Mrs Van Homrigh, celebrated by him in his published works under the name of Vanessa.//With the foul copies of her Letters and Answers in her own Writing.’ (See Sybil Le Brocquy, Cadenus, 1962 p.42).

[ top ]

Swift’s victory in the affair of Wood’s Ha’pence was called by Edmund Curtis ‘a small triumph for justice compared with the greater wrongs of the time, but it was important as the first note of Anglo-Irish opposition to the selfish deomination of Ireland by England.’ (A History of Ireland, 1936, p.267.)

Saeva indignatio/savage indignation

Vide Swift’s epitaph: ‘Hic depositum est Corpus / IONATHAN SWIFT S.T.D. / Hujus Ecclesiae Cathedralis / Decani / Ubi saeva Indignatio / Ulterius / Cor lacerare nequit. [... &c.’; as given under Quotations, supra].

Note that the epithet saeva indignatio is associated with the Roman satirist Juvenal in Ronan Sheenan’s DRB essay , on the killing of Veronica Guerin (“Though the Sky Fall”, Dublin Review of Books, No. 39, 15 July 2013) - an essay that includes the phrase ‘sed quis custodiet custodes ipsos? (Who will guard the guards themselves)’ from Juvenal’s 6th Satire of which Sheehan writes: ‘Juvenal’s sixth satire is often described as a satire upon women. That is not quite accurate. Nevertheless, the satire informs my view of the life and death of Veronica Guerin. Juvenal sees the city as being under threat on account of the actions of a significant number of women. Specifically threatened is the institution of marriage, integral to society. Juvenal offers himself as a defender of the city’s essential values. His response is to make a series of denunciations of individuals, naming names, detailing activities and offering a moral response, saeva indignatio.’ (Available online; accessed 18.09.2013.)

Cf.: William Anderson, ‘The Programs of Juvenal’s Later Books’, in Classical Philology, LVII (July 1962): ‘[...] Scaliger’s phrase about saeva indignatio was apparently written, and is always cited, to characterise the mood of every satire [by Juvenal], or at least the attitude which we should associate with the satirist. [...] It was the twisted application of such an assumption that prompted the outrageous thesis of Ribbeck’s De echte un de unechte Juvenal, almost a hundred years ago. Because he failed to find in the satires of Books 4 and 5 the techniques which belonged to the indignant Juvenal, Ribbeck felt free to label Satires 10, 12, 13, 14 and 15 as the work of an interpolator.’ (p.145; available at JSTOR - online; accessed 18.09.2013. )

Hence Scaliger is the author of the descriptive phrase, now a commonplace in regard to Juvenal. By the same token, Sheehan makes no mistake even implies an awareness that that the epithet is applied to Juvenal not by Juvenal.

Who said?: ‘After twenty times reading the whole, I never in my opinion saw so much good satire, or more good sense, in so many lines. How it passes in Dublin I know not yet; but I am sure it will be a great disadvantage to the poem, that the persons and facts will not be understood, till an explanation comes out, and a very full one. Again I insist, you must have your Asterisks filled up with some real names of real Dunces.’ (Davis, ed., Letters, Vo. III, p.32; cited in Hermann J. Real, ‘“Bacon advanced with Furious Mien”: Gulliver’s Linguistic Travels’, in Vir Bonus Dicendi Peritus, Wiesbaden 1997, p.347.)

[ top ]

W. B. Yeats, Words Upon the Window Pane, a 100-min. film dir. Mary McGuckian (1994); elegant period piece, based on one-act play by Yeats, first film by this director; Jim Sheridan as Swift; Brid Brennan and Orla Brady as ‘two women who love him too passionately’; cast incls. Ian Richardson, Geraldine Chaplin, Donal Donnelly, Gerald James, John Lynch, Gemma Craven, Gerard McSorley, and Hugh O’Connor. (Programme of Walter Reade Theatre, 1994; see details under Yeats.)

Sybil le Brocquy has argued on documentary records that he had a child called Patrick with Vanessa, the cause of his passionate quarrel with her and the sundering of his friendship with Stella (see Cadenus: a Resassessment in the Light of New Evidence of the Relationships between Swift, Stella, and Vanessa (Dublin: Dolmen 1962). the three-volume biography by Irvin Ehrenpreis (1962-83) is informed by literary, historical and psychological concerns; Bruce Arnold has written a modern biography informed by Irish interests; see also Declan Kiberd, Irish Classics (2001).

F. S. L. Lyons, Culture and Anarchy 1890-1939 (1989) defines Swift’s style defined in terms of the Anglo-Irish temperament and its tension between arrogance and insecurity, or between ‘the overcharged rhetoric of assertion and the sardonic irony of withdrawal.’ (p.22.)

R. F. Foster, Luck and the Irish: A Brief History of Change 1970-2000 (London: Allen Lane: 2007), remarks: ‘Jonathan Swift long ago pointed out that the wealth of a nation consisted in its people, and proceeded to argue that economic logic dictated that the impoverished and undernourished Irish should therefore turn to eating the children. Today’s economists similarly see “human capital” in terms of subsistence, supplying one of the explanations for Ireland’s economic miracle.’ (p.13.)

Armagh Public Library, being the library of the Protestant Primate of Ireland, holds a Ist edition copy of Gulliver’s Travels (1726), annotated for correction by Swift and valued at £30,000. In Dec. 2000 thieves entered the Library at 9.45 a.m. at first posing as researchers and tied up the young assistant Lorraine Frazer at gun-point having donned balaclavas; other artefacts stolen incl. a Geneva Bible (1611), a 23th c. Dutch missal, a miniature Koran, and 17th c. silver maces in Dublin silver valued at £25,000 each. The theft was thought to have been carried out to order for some collector. (securma@xs4all.nl; forwarded to Irish Studies list (Virginia), 15 Dec. 2000.] Note that two suspects were arrested and charged shortly afterwards. The library also contains “Pleas of the Innocents” addressed Oliver Cromwell.

Portraits (I): TCD Library holds a bust of Swift by Louis-Francois Roubillion (1945). There is also a portrait dated 1710 [var. c.1718] by Charles Jervas (c.1675-1739) in the National Gallery of Ireland. Jervas studied under Kneller and succeeded him as Royal portraitist, and did several portraits of Swift [the one in the Nat. Port. Gallery (London) being made of Swift at aetat. 43]. Swift wrote of him, ‘Do you hear anything of Jervas going, for I hate to be in town when he is there (1716). Jervas also taught Alexander Pope to paint and painted him several times, while his own translation of Don Quixote (1742) was frequently reprinted [ODNB].

Portraits (II): There is A full-length portrait of Swift by Francis Bindon, who also painted Carolan [see Oxford Ilustrated History of Ireland, 1989, p.297, & facing p.298]; note, the Bindon oil portrait of the Dean is in the King’s Hospital, Dublin (see Anne Crookshank, Irish Portraits Exhibition, Ulster Mus. 1965).Bindon’s painting bears the inscription, ‘The Drapier’s Fourth Letter to the Whole People of Ireland’ [See W. B. Yeats, A Centenary Exhibition, Nat. Gallery of Ireland 1965).

Barbadoes: Swift coined the term ‘barbadise’ as refering to the penal transportation of persons to the Barbadoes (Information supplied by Loreto Todd.)

Werburghia: Jonathan Swift was born in the parish of, and presumably baptised in the church of St. Werburgh’s, in Dublin. Samuel Johnson was married to Elisabeth Porter (his “Tetty”) in St. Werburgh’s Church in Derby - an event re-enacted every year.

The Peacock Theatre (Abbey Th., Dublin) was the venue for a discussion on Gulliver’s Travels conducted by Victoria Glendinning, John Mullan and Bruce Arnold and chaired by Mary Shine Thompson on Sunday 122 June 2008 [Notre Dame Irish Seminar announcements].

Wherefore art thou Lilliput?: The townland of Lilliput (othewise Nure) in Co. Westmeath, 5 miles south of Mullingar at the southern end of Lough Ennell, is deemed to be the place where Jonathan Swift conceived the idea of "little people" when looking back to the shore from a boat and noticing how small people appeared at that distance. Lilliput was called Nure at the time but, following the publication of Gulliver’s Travels came to be called Lilliput by the locals on the basis of the local legent. In the 18th century it was so-renamed. The place has an an association with Saint Patrick’s sister Lupita which may be recalled in its name. Lilliput House, built in the 18th century, is now home to the Lilliput Adventure Centre in the Jonathan Swift Amenity Park today. Lilliput is one of 11 townlands in the civil parish of Dysart, in the Barony of Moycashel (electoral division of Middleton / Longford-Westmeath constituency (formerly of the Westmeath constituency.)

[ top ]