| 1775-1818, b. 26 Dec., 1775, at Downpatrick (Co. Down), son of a Protestant clergyman; one of three brothers and a sister; educ. by Mr. Wilde, Downpatrick; grad. TCD, BA 1795; took deacon’s orders and entered the Church; disappointed in hopes of advancement by Bishop Dixon of Bishop of Down & Connor, a mat. uncle who himself received preferment from a boyhood friend the Prime Minister Charles James Fox; entered the Temple in London and was called to bar, 1797; wrote strenuously against the Act of Union in a pamphlet (An investigation of the legality and validity of a union, 1799) and was noticed by Fox. who brought him with him on a literary trip to Paris, meeting Napoleon Bonaparte, then First Consul — who took Trotter to be a Catholic as being Irish (hibernois); |

| returned to Ireland and embarked on a bar career but soon retired to Glasnevin; there met the case of the young woman ruined by scandal living (and dying) in Finglas which formed the topic of his novel, Stories for Irish Calumniators (1809); supported John Meade, the anti-Union candidate, in the Down bye-election of 1806 and gave a spirited answer to Robert Stewart (Lord Castlereagh); ed. Evening Herald (Dublin) in Dublin; recalled by Fox to act as his private secretary in his last days, and received no further appointment or recompense at Fox’s death in Sept. 1806; returned to Dublin and unsuccessfully conducted the Historical Register, living in Philipsburgh [now Phibsborough]; suffered the death of his brother Ruthven, killed at Buenos Aires, Jan. 1808; |

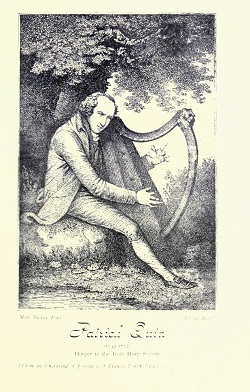

| retired to Larkhill, Co. Down on failure of the Register; adopted a poor boy to bring up as his companion and secretary; supported the Catholic hierarchy in pamphlets during the Veto Controversy regarding their right to select there own bishops without interference — making party enemies in the process; aroused by the Irish Harp Revival festivals associated with Edward Bunting in Belfast (1792), he founded the National Harp Society in Dublin with others, 1809; enlisted subscriptions from 222 members though receiving donations from only 30; formed a governing committee with num. notables [‘The List of Subscribers had to boast of a Moore, a Scott, a Walker, and the first literary characters of the day’: Walks, p.335], including his staunch friend William Liddiard (the author of the Memoirs prefixed to Walks Through Ireland, 1819] and sundry members of the patriotic movement associated with Grattan — with whom he had earlier quarrelled over the latter’s support for the Insurrection Bills; plunged money into a O’Carolan Commemoration, living at a house in Richmond which he furnished lavishly to exhibit Patrick Quin and his instrument; |

| pursued by bailiffs at behest of creditors and moved to Montalta, a villa in Co. Wicklow; there wrote Memoirs of the Last Days of Charles James Fox (1811) — a moving testimony but coloured by acrimonious sketches of political contemporaries; rejected minor government employment offered by George Canning; moved to Dalkey, Co. Dublin, where he wrote Margaret of Waldemar, a romantic novel for which he could find no publisher; still pursued by creditors, he retreated further to the Hook Peninsula in Co. Wexford and was there followed by bailliffs whom the initially welcomed as strangers but then threw out of doors; arrested for assault and placed in the Marshalsea in Wexford with some rough-handling and afterwards removed by habeas corpus to Dublin; published “Five Letters,” while in prison there writing favourably of the Prince Regent; |

| his sentence reduced to weeks rather than the years on showing evidence of friendship of the Prince Regent; married his faithful female companion in prison, called a member of a respectable family by his biographer; received a donation of $200 from Lord Yarmouth to pay off his debts; travelled to England in pursuit of advancement but returned empty-handed in 1813; settled at Balbriggan, Co. Louth where he wrote the short poem “Battle of Leipsic”, moving then moved to Rathfarnham, where he commenced his long poem The Rhine, or Warrior Kings (24 vols.; unpubl.); driven out again and retreated with his family to Tramore, Co. Waterford; gave courageous assistance to survivors of the wreck of a military transport ship returning with soldiers from Waterloo; his young ccompanion enlisted in desperation in India Company Army but was released on payment of a sum received from Lady Liverpool ($100); spent some time wandering in Wales before returning to live in Cork where he attempted again to launch a Historical Register and failed; |

| undertook a pedestrian tour of Ireland to make money by a book, producing his Walks Through Ireland (posthum. 1819), written as a series of letters to Rev. William Liddiard, then rector of Knock-marck — the probable biographer in, and publisher of, the book itself; received hospitality in cottages and cabins and assisted the poor with letters to Robert Peel, then Chief Secretary for Ireland; entered protracted period of poverty with his family and young companion, living at Hammond’s Marsh in Cork, where he contracted dysentry; visited by an orange-seller who herself seemingly ‘pined away’ after his death - survived by his wife, of whom nothing further is known; attended on death-bed the Dean of Cork; d. 29 Sept. 1818, and bur. by his own wish under the elms in Cork Cathedral church-yard; Walks appeared posthumously with an unsigned Biographical Memoir prob. by Liddiard. PI IF CAH RIA |

|

| Patrick Quinn — Irish Harper |

[ top ]

Works| Monographs (memoir & topography) |

|

| Political pamphs. |

|

| Poetry |

|

| Fiction |

|

| Journalism |

|

| Related texts |

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Walks Through Ireland, in ... 1812, 1814, and 1817; Described in a Series of Letters to an English Gentleman, with Biographical Memoirs of J. B. Trotter, Private Secretary to the Late C. J. Fox (London: Sir Richard Phillips & Co.; sold by John Cumming, Dublin 1819), pp. vi-xxxvi [Memoir], 599pp. + 8pp. adverts. 8o. [T.p. epigraph from Tacitus: “Non hic mihi primus, erga popalum Romamum fidei et constanties dies:— ex quo à deus Augusto civitate donitus sum amicos inimicosque ex vestris utilitatibus delegi; neque odio patriae (quippe proditores, etiam iis quos aantiponunt invisirunt) verum, quia Romanus, Germanis que idem conducere: et pacem quam bellum probabem.— Tacit.”]

|

|||||||||||||||

|

[ top ]

Criticism

Jim Shanahan, ‘Tales of the Time: Early Fictions of the 1798 Rebellion’, in Irish University Review, 41:1 [Irish Fiction, 1660-1830] (Spring/Summer 2011), pp.151-68.

See Frank Callery, ‘Dublin Harp Society (July 1809-Dec. 1812)’, in A History of Blindness in Irish Society (forthcoming in 2015) — supplied by the author — 16.03.2015 [ attached].

Biographical sketch: ‘His first public essay, as a writer, was a pamphlet on the subject, which he immediately sent to Mr. Fox. His opinion of it was characteristic. ‘You have put your objection to the Union [...] on right grounds; but whether there is a spirit in Ireland to act up to your principles is another quesdon. I do not know whether you have ever heard, that it is a common observation, that Irish orators are generally too figurative in their language for the English taste; perhaps I think part of your pamphlet no exception to this observation; but this is a fault, if it be a fault, easily emended. — It was a fault, which, unfortunately, he never corrected.’

| See account of the Dublin Harp Society in Frank Callery, A History of Blindness in Irish Society (forththcoming in 2015)- as attached. |

James Hardiman: Hardiman cites Trotter’s Walks ThroughIreland in claiming of Edmund Spenser that his ‘name is still remembered in the vicinity of Kilcolman, but the people entertain no sentiments of respect or affection for his memory’. (Hardiman, Irish Minstrelsy, or Bardic Remains of Ireland (1831, op. cit., p.321; see further, under Spenser, q.v. — as attached.)

Mr. E. R. Mc. C. Dix, “John Bernard Trotter”, in Irish Book Lover (Nov. 1909): ‘This eccentric individual and clever writer was born in the County Down in 1775, and educated at the grammar-school in Downpatrick, whence he proceeded to T.C.D., where he graduated in 1795. Intended for the bar, he early turned his attention to literature, and his first anti-union pamphlet brought him to the notice of Fox, who appointed him his private secretary, in which capacity he accompanied him to France. Trotter’s admiration of Fox, developed into hero worship — and it is stated that the great statesman and orator breathed his last in the arms of his faithful secretary. / Living in such an atmosphere, and with his brother E. S. Ruthven, afterwards a colleague of O’Connell, it can be well believed that Trotter flung himself with ardour into the historic election of 1805 when Castlereagh was driven from Down. Thenceforth, Trotter led a chequered existence, at one time riding in a coach and four, at another pursued by duns; now dispensing profuse hospitality, to all and sundry, anon an inmate of a debtor’s prison. He evinced great interest in the revival of the harp, establishing a Harp Society in Dublin. His later years were passed in poverty, and his misfortunes evidentally tended to unbalance his mind. He died in unspeakable destitution in Cork in 1818, tended by his young wife and a boy whom he had reared and educated from poverty. Trotter plied a busy pen. In addition to the following bibliography, for which I am indebted to Mr. E. J. Byard of the British Museum, I am inclined to attribute to him Circumstantial details of the Long Illness and Last Moments of Charles James Fox (2nd edn. London 1806, 8°., 79pp.) Whilst the biography prefixed to his posthumous and best known work, Walks Through Ireland, mentions as either written or edited by him Historical Register (Lewis, Angelsea St., Dublin, c.1806), “Margaret of Waldemar”, a poem entitled “The Battle of Leipsic”; “The Rhine or Warrior Kings” in 24 books, and Cork Historical Register, but of these I can find no existing copies.’ (IBL, III: 4, Nov. 1909, p.41.)

Bibliography [IBL]: 1. An Investigation of the Legality and Validity of a Union (Dublin 1799), 8o. 2. Stories for Calumniators; Interspersed with Remarks on the Disadvantages, Misfortunes, and Habits of the Irish ... &c., 2 vols. (Dublin 1809), 12o. 3. The Political Guardian, conducted by J. B. Trotter, No. 1 [all published] (King, Dublin 1810), 8o. 4. Memoirs of the Latter Years of the Right Honourable Charles James Fox. Third edition, xxxix+152pp. R. Phillips (London 1811), 8o. 5. Five Letters to Sir W. C. Smith ... Catholic Relief, the affairs of Ireland, and the conduct of the new Parliament. To which are added a sixth letter, with notes on the former . The third edition. 66pp. (Dublin: C. Crookes 1813), 8o. 6. Walks Through Ireland, in ... 1812, 1814, and 1817; Described in a Series of Letters to an English Gentleman, with Biographical Memoirs of J. B. Trotter (London 1819), 8o. [End].

Rolf Loeber & Magda Loeber, with Anne Mullin Burnham, A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900 (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006), briefly cite his complaint that ‘b]ooks in Irish are not to be had’ in 1812. (Walks through Ireland in ... 1812, 1814 and 1817, London 1819; p.46; Loeber & Loeber, op. cit., p.lv.)

| Bruce Stewart [RICORSO], some remarks on Walks Through Ireland |

Though often repetitious and given to lengthy flights around the natural scenery of Ireland, Trotter fills his pages with sympathetic observations about Irish country people including Catholic priests and bishops, while stating the case against the brutal imposition of the Anglican Church in Ireland as the established religion, to the great loss of the traditional clergy and faithful of Ireland. This “alteration” he traces to prejudice against the Irish considered as “Papists”- that is, adherents of a foreign Church with malevolent intent towards the English crown - an error which he sees as ensuring the disloyalty of the Irish masses who would otherwise have accepted the secular authority of the crown. in Trotter’s revision of English state politics in Irland, both Irish chieftains and foreign kings are repeatedly denominated “despots” who cruelly domineered over their people and wasted there lives in futile internecine wars with other kings on the island. From this the centralised monarchy of England saved them - goes the argument. Roderick O’Connor is his bête noir in this regard and here is animosity is traceable to a seventeenth century play in which the High King of that name did appear as a villain. Later on, however, the scene has changed and Trotter - who is an entusiastic adherent of the Irish Nation in the sense intended by the patriots of Grattan’s Parliament (although he broke with Grattan over the latter’s endorsement of the Insurrection Bills) perceived that remorseless system of rack-renting in post-Union Ireland which Maria Edgeworth also characterised as a scourge in her Irish novels is now the main abuse of power which is holding back the advance of “civilisation” in a country. In the passages dealing with the recent rebellion of the United Irishmen, Trotter consistently suggests that without the tyranny of the Anglo-Irish oligarchy over the peasantry, together with the continuing extortion of tithes by their church the Irish would not fallen in with the “sanguinary” spirit of the French revolution. |

| BS 02.03.2024.]) |

[ top ]

Walks Through Ireland [...] Preface [by Trotter]: ‘The following Letters were commenced, and the pedestrian Tours pursued, under the idea of subsequently forming an historical work on Ireland. This object has been impeded and retarded by unexpected obstacles, and the fruits of considerable observation on that country are now submitted, with great diffidence, to the public, in Letters, partly penned on the spot, and partly extracted from notes. The situation of Ireland is highly interesting. That her misery is great, and that no adequate remedy appears to have been applied, cannot be denied by impartial men. The body of her people can scarcely procure the conveniences and necessaries of life, the country seems retrograde rather than progressive. Improvident legislative provisions have turned dearth to famine; — pestilence has followed. Political injustice keeps alive the fever of the mind. / The Author submits his Letters to the judgtnent of the Public, hoping that a just consideration of his motives may lead men to excuse the defective nature of his performance.’ [End.]

Irish history (Walks Through Ireland, 1819): ‘There is little or no trade of an export nature now at Ross, and the place seems to have suffered from the war. The inhabitants are very respectable, and live together in harmony. The proportion of Catholics here, is estimated at about eight to one. This may be taken as the average of the whole county, and not less, I believe, of Wicklow. Time, you see, my dear L., has swept away, in his vast tide, millions of human beings since the arrival of the English in this neighbour-[54]hood, and yet they have made little impression on the language, religion, or mind of the country. Princes, lord-deputies, and armies, have laboured to change them, but fruitlessly. The vital stock, as if vivifying more the more it was pruned and lopped, now shoots forth its vast foliage over the land; and all the short-sighted schemes of the busy ministers of the day have ended in disappointment. What a lesson to man on pride and ambition! What a rich subject for contemplation, and for the historical student seeking truth, does this astonishing island afford! The method adopted for making it a valuable and contented member of a great empire, in whose bosom were the seeds of vast glory and an imperishable name, was wrong; persecution was used against a spirited, valiant, and feeling people. Some deputies sought fortune; others military credit; — but each had his temporary plan, and too often a narrow and bad one! The mighty surges of a nation’s suffering roared round them to no purpose. Prejudice, or mercenary views, shut their ears, and steeled their hearts. They took every account from their creatures; from men prejudiced, or wishing to deceive them. In England the truth was never known. Her ordinary and prescribed channel for information seldom or ever conveyed it. Deputies would not censure their own plans, or ministers readily attach blame to men employed and instructed by [55] themselves. No wise method has adopted to take the people out of the hands of those petty kings, who had so long before the English name was heard of, tyrannized over, and barbarized their miserable vassals. The impolitic and unjust distinction of English and Irish was kept up, in an odious and painful manner. The statutes of Kilkenny, in the Duke of Clarence’s time, treat the Irish as proscribed savages. The scheme of plantations, which has been entertained by every monarch and minister down to Charles II denotes the most crude and wretched policy. A nation brave and military, as the Irish naturally are — hardy and intellectual — not like the feeble Asiatics, or brutalized Africans, can never be persecuted into submission. They may be exterminated (though that has been seen to be difficult), but cannot be made slaves, by all the efforts of power or art. Religion, language, manners, a common country — common suffering — keep them blended and united. They bleed, but are not exhausted. From necessity they become artful and insincere. The original settlers from the mother-country, from long residence, become incorporated with them, and increase their strength. The greatness of the population in so small a space as Ireland, gives it an extraordinary energy, which, polypus like, seems uninjured by partial cutting, and defies all attempts to chain and enervate it. The first [56] English, and their successors, were doubtless brave, generous, and humane; but having fallen into a bad system, they became unwilling, unable, or ashamed to alter it. It is well known that neither kings nor ministers like advice. They weakly construe it into reprimand or assumed superiority of mind, and repel those who could assist them best, — that is, honest men telling plain truth, according to the dictates of enlightened minds. / It is perfectly awful and astonishing to read the History of Ireland, and observe the continued series of error and crime which have been pursued by various ministers, in distant times, towards that island. [...] (pp.54-56; see longer extracts — as attached.) [Trotter goes on to instance the case of Rollo of Normandy as a conquering king who took the best of local laws and improved them, winning respect and homage from the people which lasted generations.]

Fever fit: ‘In one part of the ruins, where a fine arched side-aisle was still very perfect, my guide showed some terror: I soon learned from him the cause. A person ill of fever had been left there the day before, lest he should communicate the infection to the family where he lodged. — He was left to expire! His hollow voice plaintively implored some drink; I assured him he should have it, and be taken care of, and hope revived at the moment life was ebbing fast away. In another part of this monastery I saw a hat of a departed victim of fever exposed some time ago, and at our inn I heard the following story: An American gentleman, totally a stranger, well clad and of pleasing appearance, came a few months ago to Kilmallock. He went to no inn, but wandered about the ruins, till at last entering them he was observed no more, and perhaps forgotten! He was ill, and fever burned in his veins; but where can a pennyless and forlorn wanderer turn in a country where he is without friends or money? — It happened a gentleman was ill at the inn, and required the attendance of a person to sit up every night. The inn-keeper’s son performed this humane office frequently; and very early one morning, as the stars were fading at the approach of twilight, he walked out to the monastery to refresh himself with the morning air; he heard a murmuring noise as of some human being. It was two or three days after the American gentleman’s disappearance. He recollected this, and advanced — but can I go on? — Extended on his back in a recess of a ruined aisle, the unfortunate stranger lay speechless and expiring one hand clenched the mouldering wall, the other his hat. The young man, terrified and shocked, ran for assistance. On his return this victim of misfortune was no more! — Fever had arrested his steps.’ (Quoted in Thomas Crofton Croker, Researches in the South of Ireland, London: 1824, p.68, n.; presum. taken from Walks Through Ireland, 1819.)

[ top ]

| Seamus Ua Casaide, “J. B. Trotter”, in The Irish Book Lover, Vol. I, No. 7 (Feb. 1910), 86. | |

The following supplementary list of Trotter’s works contains some items not included in the lists published in Nos. IV. and V. of this Journal:

The Halliday collection of Pamphlets in the Royal Irish Academy has copies of Nos. 1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 in above list, 5 in Mr. Bigger’s List, No. 3 in Mr. Dix’s list and possibly others. [End] |

D. J.O’Donoghue, Poets of Ireland (Dublin: Hodges Figgis 1912), lists one poem: Leipsick, or Germany Restored, A Poem (Dublin, 1813), 8vo. - and give biographical notice: ‘Born in Co. Down in 1775. B.A., T.C.D., 1795. He was intended for the law, but turned to literature, and wrote against the Union. His writings attracted the attention of Charles James Fox, who appointed him his private secretary. He almost worshipped the famous statesman, and his “Memoirs of the Latter Years’ of Fox is well-known. He wrote several other books, including “Walks through Ireland,” 1819. He died in poverty in Cork in 1819.’

Stephen Brown, Ireland in Fiction (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), lists Stories for Calumniators, 2 vols. (Dublin: Fitzpatrick 1809), ‘interpersed with remarks on the disadvantages, misfortunes, and habits of the Irish’, ded. Lord Holland; called remarkable by Brown; three stories, based on fact, recounting sad aftermath of Rebellion, and consequences if those in authority listen to slander ... told to Mr. Fitzpatrick by persons related to the victims; his remarks interspersed; considered friendly towards Catholics; favours Irish language and land reform, also higher education of women.

[ top ]

Notes

Kith & Kin: Trotter’s eldest brother Southwell became MP for Downpatrick; his younger brother William Ruthven Trotter joined the Army and died with the rank of Major in Major of His Majesty’s Eighty Third Regiment of Foot at the battle of Buenos Aires (1808); his sister Mary drew the portrait of Patrick Quin which appeared on the program of the National Harp Society.

Rev William Liddiard, who was the recipient of the letters in Walks Through Ireland (1819) was probably the author of the biographical memoirs in it and the publisher. He was married to Anna Liddiard, née Wilkinson, of Corballis Hse., Co. Meath (see RIA Dictionary of Irish Biography, RA 2009 — online). Liddiard was Wiltshire-born but held a living as rector of Culmullen in Co. Meath during 1807-10 and later at Knockmark, 1810-31. He was formerly an Army officer. Anna wrote romantic literature in the spirit of Grattan’s Parliament incl. The sgelaighe; or, A tale of old (1811), taken from an old Irish manuscript; Kenilworth and Farley Castle (1813), addressed to the “ladies of Llangollen”, and Theodore and Laura (1816), a tale in verse based on the Battle of Waterloo.

Trotters: CAPT. LIONEL TROTTER served [in the army] through the Indian Mutiny, retired in 1862, and died dies at Oxford on 6th May, aged 85 (Irish Book Lover, Vol. 3:11, June 1912, p.190.) BERNARD FREEMAN TROTTER (June 16, 1890 — May 7, 1917), was a Canadian poet who died young in World War I (1890-1917).

Patrick Bernard Trotter, author of Maximising organ donation and transplantation through the use of organs from increased risk donors (Cambridge UP 2019)

[ top ]