Gods of the Earth [p.2]

Occultists, from Paracelsus to Elephas Levi, divide the nature spirits into gnomes, sylphs, salamanders, undines; or earth, air, fire, and water spirits. Their emperors, according to Elephas, are named Cob, Paralda, Djin, Hicks respectively. The gnomes are covetous, and of the melancholic temperament. Their usual height is but two spans, though they can elongate themselves into giants. The sylphs are capricious, and of the bilious temperament. They are in size and strength much greater than men, as becomes the people of the winds. The salamanders are wrathful, and in temperament sanguine. In appearance they are long, lean, and dry. The undines are soft, cold, fickle, and phlegmatic. In appearance they are like man. The salamanders and sylphs have no fixed dwellings.

It has been held by many that somewhere out of the void there is a perpetual dribble of souls; that these souls pass through many shapes before they incarnate as men — hence the nature spirits. They are invisible — except at rare moments and times; they inhabit the interior elements, while we live upon the outer and the gross. Some float perpetually through space, and the motion of the planets drives them hither and thither in currents. Hence some Rosicrucians have thought astrology may foretell many things; for a tide of them flowing around the earth arouses there, emotions and changes, according to its nature.

Besides those of human appearance are many animal and bird-like shapes. It has been noticed that from these latter entirely come the familiars seen by Indian braves when they go fasting in the forest, seeking the instruction of the spirits. Though all at times are friendly to men — to some men — “They have,” says Paracelsus, “an aversion to self-conceited and opinionated persons, such as dogmatists, scientists, drunkards, and gluttons, and against vulgar and quarrelsome people of all kinds; but they love natural men, who are simple-minded and childlike, innocent and sincere, and the less there is of vanity and hypocrisy in a man, the easier will it be to approach them; but otherwise they are as shy as wild animals.” {320}

Sir Samuel Ferguson [pp.13 & 38]

Many in Ireland consider Sir Samuel Ferguson their greatest poet. The English reader will most likely never have heard his name, for Anglo-Irish critics, who have found English audience, being more Anglo than Irish, have been content to follow English opinion instead of leading it, in all matters concerning Ireland.

Cusheen Loo [p.33]

Forts, otherwise raths or royalties, are circular ditches enclosing a little field, where, in most cases, if you dig down you come to stone chambers, their bee-hive roofs and walls made of unmortared stone. In these little fields the ancient Celts fortified themselves and their cattle, in winter retreating into the stone chambers, where also they were buried. The people call them Dane’s forts, from a misunderstanding of the word Danán (Tuath-de-Danán). The fairies have taken up their abode therein, guarding them from all disturbance. Whoever roots them up soon finds his cattle falling sick, or his family or himself. Near the raths are sometimes found flint arrow-heads; these are called “fairy darts,” and are supposed to have been flung by the fairies, when angry, at men or cattle.

Legend of Knockgrafton [p.40]

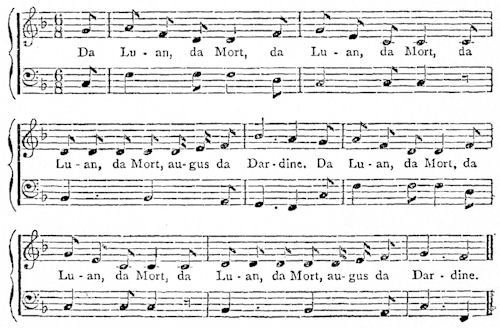

Moat does not mean a place with water, but a tumulus or barrow. The words Da Luan Da Mort agus Da Dardeen are Gaelic for “Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday too.” Da Hena is Thursday. Story-tellers, in telling this tale, says Croker, sing these words to the following music — according to Croker, music of very ancient kind:

{321}

Mr. Douglas Hyde has heard the story in Connaught, with the song of the fairy given as “Peean Peean daw feean, Peean go leh agus leffin” [pighin, pighin, dà phighin, pighin go leith agus leith phighin], which in English means, “a penny, a penny, twopence, a penny and a half, and a halfpenny.”

Stolen Child [p.59]

The places mentioned are round about Sligo. Further Rosses is a very noted fairy locality. There is here a little point of rocks where, if anyone falls asleep, there is danger of their waking silly, the fairies having carried off their souls.

Solitary Fairies [p.80].

The trooping fairies wear green jackets, the solitary ones red. On the red jacket of the Lepracaun, according to McAnally, are seven rows of buttons — seven buttons in each row. On the western coast, he says, the red jacket is covered by a frieze one, and in Ulster the creature wears a cocked hat, and when he is up to anything unusually mischievous, leaps on to a wall and spins, balancing himself on the point of the hat with his heels in the air. McAnally tells how once a peasant saw a battle between the green jacket fairies and the red. When the green jackets began to win, so delighted was he to see the green above the red, he gave a great shout. In a moment all vanished and he was flung into the ditch.

Banshee’s Cry [p.108]

Mr. and Mrs. S. C. Hall give the following notation of the cry:

Omens [p.108]

We have other omens beside the Banshee and the Dullahan and the Coach-a-Bower. I know one family where death is announced by the cracking of a whip. Some families are attended by phantoms of ravens {322/322] or other birds. When McManus, of ’48 celebrity, was sitting by his dying brother, a bird of vulture-like appearance came through the window and lighted on the breast of the dying man. The two watched in terror, not daring to drive it off. It crouched there, bright-eyed, till the soul left the body. It was considered a most evil omen. Lefanu worked this into a tale. I have good authority for tracing its origin to McManus and his brother.

A Witch Trial [p.146]

The last trial for witchcraft in Ireland — there were never very many — is thus given in MacSkimin’s History of Carrickfergus: “1711, March 31st, Janet Mean, of Braid-island; Janet Latimer, Irish-quarter, Carrickfergus; Janet Millar, Scotch-quarter, Carrickfergus; Margaret Mitchel, Kilroot; Catharine M’Calmond, Janet Liston, alias Seller, Elizabeth Seller, and Janet Carson, the four last from Island Magee, were tried here, in the County of Antrim Court, for witchcraft.”

Their alleged crime was tormenting a young woman, called Mary Dunbar, about eighteen years of age, at the house of James Hattridge, Island Magee, and at other places to which she was removed. The circumstances sworn on the trial were as follows:

“The afflicted person being, in the month of February, 1711, in the house of James Hattridge, Island Magee (which had been for some time believed to be haunted by evil spirits), found an apron on the parlour floor, that had been missing some time, tied with five strange knots, which she loosened.

“On the following day she was suddenly seized with a violent pain in her thigh, and afterwards fell into fits and ravings; and, on recovering, said she was tormented by several women, whose dress and personal appearance she minutely described. Shortly after, she was again seized with the like fits, and on recovering she accused five other women of tormenting her, describing them also. The accused persons being brought from different parts of the country, she appeared to suffer extreme fear and additional torture as they approached the house.

“It was also deposed that strange noises, as of whistling, scratching, etc., were heard in the house, and that a sulphureous smell was observed in the rooms; that stones, turf, and the like were thrown about the house, and the coverlets, etc., frequently taken off the beds and made up in the shape of a corpse; and that a bolster once walked out of a room into the kitchen with a night-gown about it! It likewise appeared in evidence that in some of her fits three strong men were scarcely able to hold her in the bed; that at times she vomited feathers, cotton yarn, pins, and buttons; and that on one occasion she slid off the bed and was laid on the floor, as if supported and drawn by an invincible power. The afflicted person was unable to give any evidence on the trial, being during that time dumb, but had no violent fit during its continuance.” {323}

In defence of the accused, it appeared that they were mostly sober, industrious people, who attended public worship, could repeat the Lord’s Prayer, and had been known to pray both in public and private; and that some of them had lately received communion.

Judge Upton charged the jury, and observed on the regular attendance of accused at public worship; remarking that he thought it improbable that real witches could so far retain the form of religion as to frequent the religious worship of God, both publicly and privately, which had been proved in favour of the accused. He concluded by giving his opinion “that the jury could not bring them in guilty upon the sole testimony of the afflicted person’s visionary images.” He was followed by Judge Macarthy, who differed from him in opinion, “and thought the jury might, from the evidence, bring them in guilty,” which they accordingly did.

This trial lasted from six o’clock in the morning till two in the afternoon; and the prisoners were sentenced to be imprisoned twelve months, and to stand four times in the pillory of Carrickfergus.

Tradition says that the people were much exasperated against these unfortunate persons, who were severely pelted in the pillory with boiled cabbage stalks and the like, by which one of them had an eye beaten out.

T’yeer-na-n-Oge [p.200]

“Tir-na-n-óg,” Mr. Douglas Hyde writes, “The Country of the Young,” is the place where the Irish peasant will tell you geabhaedh tu an sonas aer pighin, ‘you will get happiness for a penny,’ so cheap and common it will be. It is sometimes, but not often, called Tir-na-hóige; the ‘Land of Youth.’ Crofton Croker writes it, Thierna-na-noge, which is an unfortunate mistake of his, Thierna meaning a lord, not a country. This unlucky blunder is, like many others of the same sort where Irish words are concerned, in danger of becoming stereotyped, as the name of Iona has been, from mere clerical carelessness.”

The Gonconer or Gancanagh [Gean-canach]. [p.207]

O’Kearney, a Louthman, deeply versed in Irish lore, writes of the gean-canach (love-talker) that he is “another diminutive being of the same tribe as the Lepracaun, but, unlike him, he personated love and idleness, and always appeared with a dudeen in his jaw in lonesome valleys, and it was his custom to make love to shepherdesses and milk-maids. It was considered very unlucky to meet him, and whoever was known to have ruined his fortune by devotion to the fair sex was said to have met a gean-canach. The dudeen, or ancient Irish tobacco {324} pipe, found in our raths, etc., is still popularly called a gean-canach’s pipe.”

The word is not to be found in dictionaries, nor does this spirit appear to be well known, if known at all, in Connacht. The word is pronounced gánconâgh.

In the MS. marked R.I.A. 23/E. 13 in the Roy. Ir. Ac., there is a long poem describing such a fairy hurling-match as the one in the story, only the fairies described as the shiagh, or host, wore plaids and bonnets, like Highlanders. After the hurling the fairies have a hunt, in which the poet takes part, and they swept with great rapidity through half Ireland. The poem ends with the line —

“’S gur shiubhail mé na cúig cúig cúige ’s gan fúm acht buachallán buidhe;”

“and I had travelled the five provinces with nothing under me but a yellow bohalawn (rag-weed).” — [Note by Mr. Douglas Hyde.]

Father John O’Hart [p.220].

Father O’Rorke is the priest of the parishes of Ballysadare and Kilvarnet, and it is from his learnedly and faithfully and sympathetically written history of these parishes that I have taken the story of Father John, who had been priest of these parishes, dying in the year 1739. Coloony is a village in Kilvarnet.

Some sayings of Father John’s have come down. Once when he was sorrowing greatly for the death of his brother, the people said to him, “Why do you sorrow so for your brother when you forbid us to keen?” “Nature,” he answered, “forces me, but ye force nature.” His memory and influence survives, in the fact that to the present day there has been no keening in Coloony.

He was a friend of the celebrated poet and musician, Carolan.

Shoneen and Sleiveen [p.220]

Shoneen is the diminutive of shone [Ir. Seón ]. There are two Irish names for John — one is Shone, the other is Shawn [Ir. Seághan ]. Shone is the “grandest” of the two, and is applied to the gentry. Hence Shoneen means “a little gentry John,” and is applied to upstarts and “big” farmers, who ape the rank of gentleman.

Sleiveen, not to be found in the dictionaries, is a comical Irish word (at least in Connaught) for a rogue. It probably comes from sliabh, a mountain, meaning primarily a mountaineer, and in a secondary sense, on the principle that mountaineers are worse than anybody else, a rogue. I am indebted to Mr. Douglas Hyde for these details, as for many others.

{325/325]

Demon Cat [p.229]

In Ireland one hears much of Demon Cats. The father of one of the present editors of the Fortnightly had such a cat, say county Dublin peasantry. One day the priest dined with him, and objecting to see a cat fed before Christians, said something over it that made it go up the chimney in a flame of fire. “I will have the law on you for doing such a thing to my cat,” said the father of the editor. “Would you like to see your cat?” said the priest. “I would,” said he, and the priest brought it up, covered with chains, through the hearth-rug, straight out of hell. The Irish devil does not object to these undignified shapes. The Irish devil is not a dignified person. He has no whiff of sulphureous majesty about him. A centaur of the ragamuffin, jeering and shaking his tatters, at once the butt and terror of the saints!

A Legend of Knockmany [p.266].

Carleton says — “Of the grey stone mentioned in this legend, there is a very striking and melancholy anecdote to be told. Some twelve or thirteen years ago, a gentleman in the vicinity of the site of it was building a house, and, in defiance of the legend and curse connected with it, he resolved to break it up and use it. It was with some difficulty, however, that he could succeed in getting his labourers to have anything to do with its mutilation. Two men, however, undertook to blast it, but, somehow, the process of ignition being mismanaged, it exploded prematurely, and one of them was killed. This coincidence was held as a fulfilment of the curse mentioned in the legend. I have heard that it remains in that mutilated state to the present day, no other person being found who had the hardihood to touch it. This stone, before it was disfigured, exactly resembled that which the country people term a miscaun of butter, which is precisely the shape of a complete prism, a circumstance, no doubt, which, in the fertile imagination of the old Senachies, gave rise to the superstition annexed to it.” |