Literatura Irlandesa / LEM2055

Dr. Bruce Stewart

Reader Emeritus in English Literature

University of Ulster

|

|

|||

| Irish Myths - Told by Marie Heaney | Critical Commentaries | ||

| Irish Myths - Told by Lady Gregory | The Oxford Companion | ||

[ All the files given on this page are PDFs and can be read in-frame (i.e., inside RICORSO Classroom) or downloaded to the folder of your choice. ]

|

| Literary Texts | Commentary |

[ A Short Introduction to Irish History and Culture ]

| On separate pages ... | ||

| A Map of Gaelic Ireland | Album of Gaelic Ireland | |

|

||

§

Literary Texts for the Study of Irish Mythology

| The Irish Myths - Retold by Marie Heaney | ||

| —from Over Nine Waves: A Book of Irish Legends (London: Faber & Faber 1994) | ||

| Tales from The Mythological Cycle | ||

|

in frame | download |

|

in frame | download |

|

in frame | download |

| Tales from The Ulster Cycle | ||

|

in frame | download |

|

in frame | download |

|

in frame | download |

|

in frame | download |

[ See extracts from John Millington Synge’s Deirdre of the Sorrows (1907) - as attached. ]

§

| Cuchulain of Muirthemne (1902) translated by Lady Gregory | ||

| ‘The best book to come out of Ireland in our time.’ (W. B. Yeats, Preface.) | ||

| “The Sons of Usnach” [aka “Deirdre’s Lamentations”] (from The Book of Ulster) | in frame | download |

| Cuchulain of Muirthemne (1902) - incorporates Táin Bó Cuailgne (from The Book of Leinster) | in frame | download |

| W. B. Yeats’s Preface to Cuchulainn of Muirthemne (1902) | in frame | download |

| Gods and Fighting Men (1904) translated by Lady Gregory | ||

| “Coming of the Tuatha” and “Lugh of the Long Hand” (orig. given in The Book of Invasions) | in frame | download |

| “The Fate of the Sons of Tuireann” - being the story commonly known as “Deirdre of the Sorrows” | in frame | download |

§

Critical Commentaries on Irish Society and Its Culture

|

||

| Myles Dillon & Nora Chadwick, The Celtic Realms (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1967) - Part I [Chap. 1]: “Discovery of the Celts”. | in frame | download |

—, The Celtic Realms (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1967) - Part II [Chap. 2]: “History and Geography of the British Isles”. |

in frame | download |

* —, The Celtic Realms (London: W&N 1967) - Part III [Chap. 7]: Celtic Religion and Mythology and the [...] Otherworld”. |

in frame | download |

| Myles Dillon, ‘Celtic Religion and Celtic Society’, in The Celts, ed. Joseph Raftery (Cork: Mercier Press 1964), pp.59-71 | in frame | download |

—, Introduction to the Irish Sagas, adapted by Bruce Stewart for RICORSO from a radio talk of 1959. |

in frame | download |

* —, “The Wooing of Etain [Tochmarc Étaíne]’, a radio talk of 1959 (adapted for RICORSO by Bruce Stewart). |

in frame | download |

| *Nora Chadwick, “Religion and Mythology: The Evidence of the Celts”, in The Celts (1971), [Chap. 6, Sect. 3]. | in frame | download |

| Douglas Hyde, “Early Irish Literature’, in Irish Literature, ed. Justin MacCarthy, Vol. III (Phil.: John Morris 1904). | in frame | download |

| Charles Doherty, “Kingship In Early Ireland’, in Tara: [...] Kingship and Landscape, Edel Bhreathnach (Dublin 2005). | in frame | download |

—, “Latin Writing in Ireland’, in Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, ed. Seamus Deane (Derry: Field Day Co 1991). |

in frame | download |

*Séamus Mac Mathona, “Paganism and Society in Early Ireland”, in Irish Writers and Religion, ed. Robert Welch (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1992). |

in frame | download |

| Patricia Monaghan, “Celtic Religion”, in An Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore (Facts on File 2008). [This is a jpeg file framed in an html page.] | in frame | in frame |

| [ See a sample of these commentaries in short quotations - below. ] | ||

§

|

||||

“Archaelogy” - dealing with the ethnic and cultural history of Early Ireland |

in-frame | download | ||

“Cuchullain” [hero of the Ulster Cycle] |

in-frame | download | ||

“Divisions” [the system of five-fold division in Ireland] |

in-frame | download | ||

“Fionn Mac Cumhaill / Finn McCool” [hero of the Fionn Cycle] |

in-frame | download | ||

“Irish Mythology” [belief-system of the insular Celts] |

in-frame | download | ||

“Lughnasa” [feast day dedicated to the god Lugh] |

in-frame | download | ||

| sídh [fairies - hence ‘banshee’ from bean sí (woman of the fairies)] | in-frame | download | ||

| “Tara” [the seat of the Irish High Kings] | in-frame | download | ||

| Táin Bó Cuailgne [Cattle-raid of Cooley] - the Irish epic | in-frame | download | ||

| “Tale types” [Gaelic narrative genres] | in-frame | download | ||

“Ulster Cycle” [Ulster Cycle] |

in-frame | download | ||

| See also .. | ||||

“The Celts” |

in-frame | download | ||

“Celtic Language” |

in-frame | download | ||

[ top ]

| Translations of Irish Mythology |

Translations of the Irish myths found if the few surviving manuscripts such as 12th-century The Book of Leinster and the 14th-century Yellow Book of Lecan (Leabhar na hUidre) - both late copies of earlier compilations which may have been made before the Viking invasion - began to come out in scholarly editions from the mid-nineteenth century. Romanticised abbreviations of them by author such as James Standish O”Grady, promoting the “Heroic History” of Ireland, followed in the 1880s and 1890s. In 1902 Lady Gregory, one of the founders of the Irish Literary Revival - though herself an Anglo-Irish aristocrat - translated the tales of the Ulster Cycle revolving around Cuchulainn and those of the Mythological Cycle - revolving around Fionn Mac Cumhall - as Cuchulainn of Muirthemne (1902) and Gods and Fighting Men (1904) respectively. The style of English which she employed for the translation was called Kiltartanese after the dialect of Hiberno-English spoken by the common people on her own estate at Coole Park in Co. Galway. Interesting and attractive as her work is, it is not modern in the sense of sharing the habits of speech of modern readers - indeed, it demands that we accept a highly-rafted dialect as the proper language of the literature in question. It is easy to see that this is not the case and that she was, in fact, engaged him her own project or equating Irish myth and legend with the folklore records whcih she took among the peasantry of the West of Ireland - and which therefore reflect her infatuation with a particular Hiberno-English pattern of expression. Aside from that, she is inevitably guilty of a high degree of Victorian Romanticism and, indeed, her Cuchulain was written in the last year of Queen Victoria’s life. For the modern reader, therefore, the translation-version by Marie Heaney (1994) - which is really a rewrite of the story in various English versions - is much more approachable. It sounds like a modern story-teller, perhaps on a radio broadcast. Another more strenuous rendition of the Gaelic material exists in the form of the translation made by the distinguished poet Thomas Kinsella (1928-2019) with illustrations by Louis le Brocquy which have been reproduced on these pages. Kinsella”s translation is noted for the rawness with which he follows the original phrases in order to capture their original poetic force but is not easily readable in a second-language context. It is therefore Marie Heaneyְs version which we will use as the standard translation for our course. Accordingly, I have divided the index between passages translated by Lady Gregory and Marie Heaney for comparison, if you wish. The pages from Marie Heaney are digitally scanned while those from Lady Gregory are given in text-form. A full copy of Gregory’s Cuchulain of Muirthemne (1902) is also given here but text and file are both unusually large (i.e., 335pp. or 255KB). A similar version of Gods and Fighting Men (1904) is available at on the Sacred Texts website but it is not copied full here. You can find it at Sacred Texts [online] or in another digital edition formatted for various applications including Kindle at Gutenberg Project [online]. |

| For further introductory remarks - see below. |

| Douglas Hyde, ‘Early Irish Literature’, in Irish Literature, ed. Justin MacCarthy, (Phil.: John Morris & Company 1904), Vol. II. |

There are three well-marked classes of sagas, dealing with different periods and different materials, and outside of these are many isolated ones dealing with minor incidents. The three chief cycles of saga-telling are the mythological, the Red Branch, and the Fenian cycles. The first of these is really concerned with the most ancient tales of the early Irish pantheon, in which what are obviously supernatural beings and races are more or less “euhemerized,” or presented as real men and heroes. Lugh the long-handed, the Dagda, and Balor of the Evil Eye, who figure in these stories, are evidently ancient gods of Good and Evil, while the various colonizations of Ireland by Partholan, the Nemedians, and the Tuatha De Danann, may well be the Irish equivalent of the Greek legend of the three successive ages of gold, silver, and brass. The next great cycle of story-telling, the Heroic, Ultonian, or Red Branch [xi] cycle, as it is variously called, is that in which Cuchulain and Conor mac Nessa king of Ulster are the dominating figures, and the third great cycle deals with Finn mac Cum hail, his son Oisin, or Ossian, the poet, his grandson Oscar, and the High Kings of Ireland, who were their contemporaries. In addition to these there are a number of short groups of tales or minor cycles, and many completely independent sagas, most of them dealing, as these greater cycles do, only with pre-Christian times, though a few belong to the very early medieval period. All these Irish romances are compositions upon which more or less care was evidently bestowed in ancient times, as is evident by their being shot through and through with verses. These verses often amount to a considerable portion of the whole saga, and Irish versification is usually very elaborate and not the work of any mere inventor or story-teller, but of a highly trained technical poet. Very few sagas, and these chiefly of the more modern ones, are written in pure prose. |

| See full-length version of this chapter - download. |

| Myles Dillon & Nora Chadwick, The Celtic Realms [History and Civilisation] (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1967), 355pp. |

| The attempt to present the Celts in history as one people, with a common tradition and a common character, is new, and in some degree, experimental. It seems to us to have been justified beyond our expectations, inasmuch as there does emerge in the history and institutions and religion, in the art and literature, perhaps even in the language, a quality that is distinctive and common to the Celts of Gaul, of Britain and of Ireland. We hesitate to give it a name: it makes a contrast with Greek temperance, it is marked by extremes of luxury and asceticism, of exultation and despair, by lack of discipline and of the gift for organising secular affairs, by delight in natural beauty and in tales of mystery and imagination, by an artistic sense that prefers decoration and pattern to mere representation. Matthew Arnold called it the “Celtic Magic.” (Preface.) |

| See extensive notes from this work - download. |

| Nora Chadwick, The Celts (Penguin 1971), “Religion and Mythology: The Evidence of the Celts” [Chap. 6, Sect. 3], pp.168-82. |

| In concluding this survey of Irish mythology, I would call attention to the naturalness with which men, women and the gods meet and pass in and out of the natural and the supernatural spheres. In many circumstances there does not seem to have been any barrier. At times a ‘druidical’ mist surrounds the hero and heralds the approach of the god; at others the god appears from across the sea and perhaps a lake; sometimes a human being enters a sídh or burial mound, either as a human being or as a bird; but normally the two-way traffic between the [181] natural and the supernatural is open. In general, however, though by no means invariably, return to the land of mortals is difficult and sometimes impossible for mortals who have visited the abode of the dead.

A beautiful dignity hangs over Irish mythology, an orderliness, a sense of fitness. All the gods are beautifully dressed and most are of startlingly beautiful appearance. It is only by contrast with other mythologies that we realize that the ‘land of promise’ contains little that is ugly. There is no sin and no punishment. There are few monsters, nothing to cause alarm, not even extremes of climate. There is no serious warfare, no lasting strife. Those who die, or who are lured away to the Land of Promise, the land of the young, leave for an idealized existence, amid beauty, perpetual youth, and goodwill. The heathen Irish erected a spirituality - a spiritual loveliness which comes close to an ideal spiritual existence. [...; &c.] |

| See full-length version of this chapter - download. |

|

Séamus Mac Mathona, ‘Paganism and Society in Early Ireland’, in Irish Writers and Religion, ed. Robert Welch (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1992) |

[...] |

| See full-length version of this chapter - download. |

|

Marie Heaney, Over Nine Waves: A Book of Irish Legends (London: Faber & Faber 1994). Preface |

|

| ([Signed:] August 1993: Dublin.) |

§

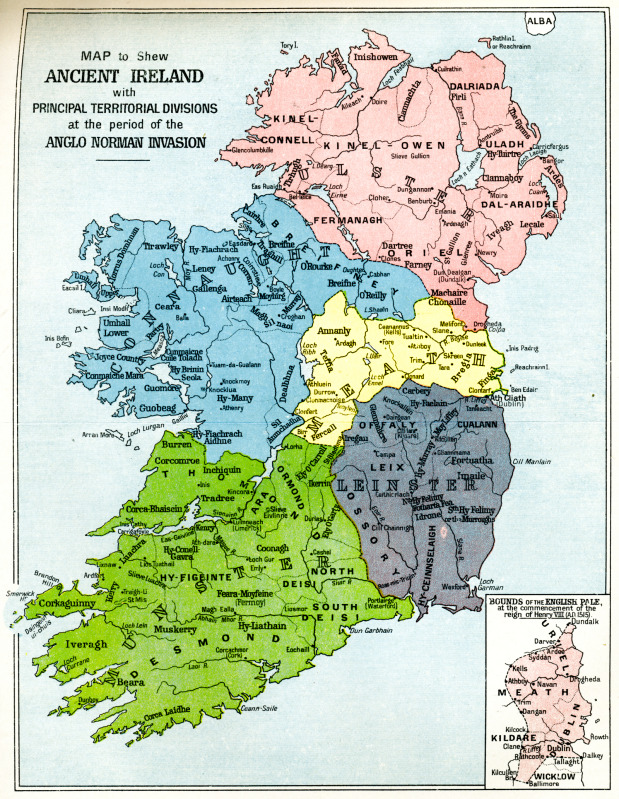

| The Five Provinces of Ireland (Encyc. Brit. 1911 Edn.) |

|

Ulster, Connacht, Leinster, Munster and Meath [the hidden ‘middleֻ kingdom] |

| Understanding the Irish provinces or (‘divisions’) |

|

|

| [ back ] | [ top ] |