Maria Edgeworth's Castle Rackrent

Literatura Irlandesa / LEM2055

Dr. Bruce Stewart

Reader Emeritus in English Literature

University of Ulster

Appendix |

| Introduction |

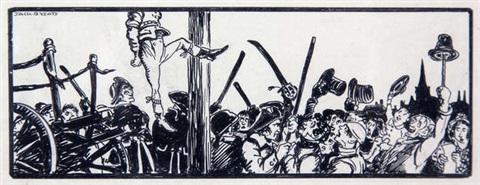

Maria Edgeworth (1767-1849) is usually regarded as the author of the first Irish novels, with special emphasis on Castle Rackrent (1800) in which the anatomy of Anglo-Irish society - to which she belonged - is revealed in a peculiarly glaring light, as if by x-ray long before the date of that invention. Equally, the notion of a Colonial Subconscious might be applied - or else a form of channelling by means of which the mentality of the Colonial Other infiltrates and even overwhelms that of the author. The means by which this is made possible is the use of a household servant, Thady Quirk, as narrator - a character whom Edgeworth has said she based on the “real-life” household servant John Langan whose voice she seemed to hear beside her as she was writing. It is the strange intimacy of this imaginative relationship which holds the critics' attention today since, in the course of his chronicle or “history” of the Rackrent family, Thady reveals a thousand details about their conduct down the generations which clearly casts them in a very different light from the one he explicit proposes: instead of being admirable, they form a selfish, wasteful, self-deluding, bibulous and wildly destructive cohort of irresponsible land-owners whose resemblance to Edgeworth’s own class seems strangely certain in spite of her insistence that the novel depicts the “manners of the squires” in the years before 1782 when, in fact, the Edgeworth’s themselves migrated from Oxfordshire to take up an Irish estate inherited by her father. The significance of 1782 is two-fold: not only is it the date when Richard Lovell Edgeworth arrived in Co. Longford with his children but it is also the date then the Protestant proprietors of Ireland gained Legislative Independence from England for their Parliament in Dublin. Since the victory of William III over James II at the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, the Protestants had succeeded in building a handsome capital city which included as the gem in its crown a magnificent Parliament incorporating the House of Lords and the House of Commons, designed by a number of brilliant architects including Richard Cassells and Jamea Gandon. (Gandon was also responsible for the magnificent Four Courts and the Custom House, both facing the Liffey River across a quay as fine as those in Paris if smaller in scale, as the river itself is smaller.) It was, in fact, the threat of the French Revolution spreading to Ireland which permitted the Anglo-Irish to form the Irish Volunteers, a private army which they used in turn to extort “liberty” from the British Government. Led by the famed parliamentary speaker Henry Grattan, the “national” party used their newly-acquired “muscle” to gain Legislative Independence so that, on 16th April 1782, Grattan was able to say: “Esto perpetua!” in the Irish House of Commons. Yet, in spite of that fervent declaration. the Protestant Parliament which he thus led to freedom did not last long. In 1798 the United Irishmen - primarily a group of Presbyterians radicals influenced by republican ideas from France - started a rebellion, in which they were joined by the Jacobite peasantry in the South of Ireland (formerly supporters of King James “across the water” and latterly French republicans). After some successes this guerrilla army was badly beaten by the British, resulting in numerous brutal executions. Frightened by the rebellion, the aristocratic leaders of Protestant Ireland - landlords all - voted their Parliament out of existence and, after January 1801, Ireland’s MPs began travelling to the "Imperial Parliament" in Westminster (London) - as they would continue to do until the Irish War of Independence of 1919-22. It is in the gap between the winning of Legislative Independence in 1782 and the Act of Union in 1800 that Maria Edgeworth wrote her Irish novels. There are chiefly two of these, Castle Rackent (1880) and The Absentee (1812) - one a portrait of an Anglo-Irish land-owning family in decline and the other a stern critique of the political and economic system that supports them. Besides its ostensible character as a ’rollicking’ account of the Anglo-Irish gentry in the wild days before a reforming spirit entered to the Protestant Parliament in Dublin, Castle Rackrent is an extraordinary window on the conflicting forces of the emerging divisions between landowners and their Irish Catholics tenants. Since the novel is narrated by a household servant (Thady Quirk) who is himself one of the peasants - and whose son eventually comes into possession of the property by legal wiles - it seems as if Maria Edgeworth had dire premonitions of the historical outcome. Otherwise viewed, she was possessed by a kind of superrogatory intuition of what her own class might look like when viewed from the standpoint of the other. In the second-named novel, she follows the Irish journey of a son of an Anglo-irish family who are spending their time and their fortune at fashionable English resorts such as Bath, which she depicts in fine detail. In Ireland, the young Lord Colambre finds that the lives of his tenants are ruined by the extortions of a "middle-man to "rackrents" to his own profit at the orders of Colambre's father, Lord Clonbrony, who owns the land. The blame is thus shifted from the aristocracy to their native agents. Needless to say, Lord Colambre marries a lovely member of the ousted Gaelic aristocracy and the injustices are resolved. No such union ever happened in reality and the divisions were only resolved by revolution in the decades and centuries ahead. Let us now meet the Rackrents - Sir Patrick, Sir Condy, Sir Connelly with their several wives whose harum-scarum version of civic society in Ireland constituted the scandal that Maria Edgeworth hoped to reform - and which her “family servant” Thady Quirk (aka John Langan) was justified in regarding as as a clear demonstration of the fact that no such class deserved a footing in the country - compared, that is, with the lost Gaelic aristocracy which had shipped overseas in the previous century - for which reason his own son Jason is about to strip the Rackrents of their estate in his character as an Catholic lawyer, not entirely unlike Daniel O’Connell, the Liberator who won Catholic Emancipation for his people in 1829 ... |

| See some opinions of Maria Edgeworth - infra. |

[ Note: All files listed on this page are downloadable MS Word documents which can be read and saved on your own hard-drive. ]

Primary Texts

| “Preface to Castle Rackrent” (complete) |

|

| “Castle Rackrent - Part I: Opening pages” | |

| “Maria Edgeworth - General Opinions(Quotations)” | |

| “Maria Edgeworth - Her remarks on Castle Rackrent” | |

[ A full copy of Castle Rackrent can be reached at RICORSO > Library > “Irish Classics” - via index or as attached.]

[ top ]

Secondary Texts

| “Irish Critics on Castle Rackrent” [Emily Lawless, Daniel Corkery and Paul Murray] | |

| “Recent Critics on Castle Rackrent” [Emily Lawless, Daniel Corkery and Paul Murray] | |

| “Bogland and Bogmen” (essay by Bruce Stewart) | download |

[ top ]

|

||

| “Maria Edgeworth” (1767-1849) | |

|

| “Castle Rackrent” (1800) | ||

| “The Absentee” (1812) | ||

| “The United Irishmen's Rebellion” (1798) | ||

| “The Act of Union” (1800-01) | ||

[ You can greatly extend your knowledge of this writer by browsing in RICORSO - online. ]

[ top ]

| The Opinions of Maria Edgeworth |

|

Social class: ‘The question, whether society could exist without the distinction of ranks, is a question involving a variety of complicated discussions, which we will leave to the politician and the legislator … At present it is necessary that the education of different ranks should, in some respects, be different. They have few ideas, few habits in common.’ (Preface to The Parent’s Assistant, 1796). The Native Irish: ‘The lower Irish are such acute observers, that there is no deceiving them as to the state of the real feelings of their superiors. They know the signs of what passes within, more perfectly than any physiognomist, who every studied the human face, or human head.’ (Memoirs, 1820, ii., p.241; quoted in Watson, ed., Castle Rackrent, World Classics, OUP, 1964, 1969, Introduction, p.xxiv.) Irish Catholics: ‘Catholics can and should have equal rights [but] must not have a dominant religion.’ (Quoted in Michael Hurst, Maria Edgeworth and the Public Scene, Macmillan 1969, p.223.) Irish language: ‘The Irish language is now almost gone into disuse, the class of people all speak English except in their quarrels with each other …’ (1782; quoted in Marilyn Butler, Maria Edgeworth, p.91; cited in Rolf Loeber & Magda Loeber, A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900, Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006, p.lvii.) Ireland in 1834: ‘It is impossible to draw Ireland as she how is in the book of fiction - realities are too strong, party passion too violent, to bear to see, or care to look, at their faces in a looking-glass. The people would only break the glass and curse the fool who held the mirror up to nature - distorted nature, in a fever |

| [See further extracts attached; see also Quotations from Maria Edgeworth in RICORSO > Maria Edgeworth > Quotations - online.] |

[ top ]

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| [ download ] | |

|

|

| [ back ] | [ top ] |