Life

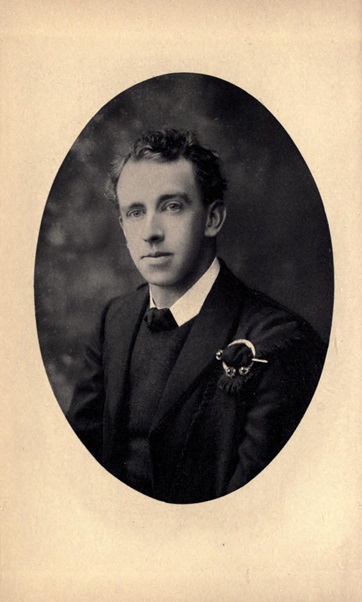

| 1878-1916 [Thomas Stanislaus MacDonagh] b. 1 Feb., Cloughjordan Co. Tipperary; son of Joseph MacDonagh, a teacher and the son of a ‘hedge-school teacher’ so-named in 1851 Census, with Mary Louise (née Parker), dg. of English printer in Dublin University Press; 3 brs., 2 sis.; ed. by his father until his death in 1894; ed. Rockwell College, Co. Tipperary, matriculated 1896; joined Holy Ghost Fathers at Rockwell, but gained permission to leave the Congregation, 1901, giving up his vocation after personal religious crisis, which is subject of his first poetry collection Through the Ivory Gate; joined Gaelic League ‘for a lark’, 1901 and held offices in league branches in Kilkenny and Fermoy; taught French and English St. Kieran’s, Kilkenny, 1901; |

| moved to St Colman’s Monastery School, Fermoy, Co. Cork, Sept. 1901-08; became Vice-President of League branch, and twice-weekly Irish teacher; received letter from Yeats recommending him to ‘translate from the Irish … literally, preserving as much of the idiom as possible’); issued Through the Ivory Gate (1902), 55 poems, ded. to Yeats; further poems, April and May (1903) and The Golden Joy (1906), the latter showing influence of his reading of Plotinus and Walt Whitman; fnd. member Association of Secondary teachers, with Patrick J. Kennedy (first President); English and French teacher and assistant headmaster in Patrick Pearse’s school, St. Enda’s, Ranelagh, 1908; |

| applied for Inspectorship of Schools, but rejected; initially continued teaching during studies at UCD; frustrated love affair with Mary Maguire (later Mrs. Padraic Colum), seen in poems, Songs of Myself (1910); ceased teaching late spring and went to Paris to prepare for finals in French, 1910, returning in Sept.; BA 1910; lived briefly in solitude at Grange House Lodge at foot of Dublin mountains; rejoined Pearse at St. Enda’s and began studies for M.A. and also employment as asst. lecturer at UCD, under Prof. Robert Donovan, 1911; resumed teaching at St. Enda’s, 1911-12; Abbey production of When the Dawn is Come (Oct. 1908, Abbey Theatre), concerning the heroism of Turlough McKiernan, a poet and member of the Supreme Council of Ireland who dies of wounds in a war of national liberation; fnd. The Irish Review, with David Houston assisted by Padraic Colum and James Stephens; later co-edited same with Joseph Mary Plunkett, 1911; |

| m. Muriel Gifford, 3 Jan. 1912 - she being the sister of Grace Gifford who married Joseph Mary Plunkett in Kilmainham, 1916 (dgs. of Frederick Gifford whose two son were baptised Catholic but brought up in the Church of Ireland by his wife Isabella [née Burton] - their four dgs. being baptised Protestant according to the custom of the day); wrote Metempyschosis, or A Mad World, one-act play (Theatre of Ireland, April 1912), set in Castle Winton, nr. Drogheda, and containing a caricature of Yeats as Earl Windton-Winton de Winton, ‘voluble, excitable, earnest, visionary victim of … enthusiasm nearly forty years age’; a son, Donagh, b. 22 Nov. 1912; issued Lyrical Poems (1913); joined committee of Irish Volunteers, 1913; M.A. Thesis, Thomas Campion and the Art of English Poetry (1913); appt. Director of Irish Volunteers, 1913; co-founder Irish Theatre in Hardwicke St. with Edward Martyn and Plunkett, and managing director [c.1914]; |

| with Bulmer Hobson, he organised the gun-running march to Howth, July 1914; contrib. anti-conscription articles in The Irish Review (Sept.-Nov. 1914), leading to its suppression; wrote a one-act play Pagans, dealing with an incompatible couple who agree to go their own ways, performed 1915; a dg., Barbara, b. March 1915; became the object of an open Letter by Francis Sheehy-Skeffington reproaching him for ‘boasting of … a new militarism’, May 1915; joined IRB and organised O’Donovan Rossa’s funeral, 1 Aug. 1915; joined IRB, Sept. 1915; co-opted onto secret military committee of the Irish Volunteers, April 1916; did not sleep at home for two weeks prior to the Rising, though visiting every day with an armed guard; did not notify his wife of the planned Rising but later wrote on the eve of execution, ‘but for your suffering this would be all joy and glory’; gave his last university lecture on the subject of Jane Austen [‘Ah, there’s nobody like Jane, lads’]; |

| became a signatory of the Republican proclamation, Easter 1916; occupied Jacob’s Mill, Bishop St., with rank of Commandant; surrendered to General Lowe at 3.15 pm on Sunday, 30th April; encouraged younger men to escape in mufti (‘we will be gone and you must carry on the fight‘); held in Richmond Prison; court-martialled 2 May, and executed 3.30 a.m., 3 May; survived by Muriel and their two children, Donagh MacDonagh [q.v.] and Barbara; Muriel -who had converted to Catholicism to raise the children - died tragically in a swimming accident nr. Skerries on 9 July 1917 while swimming to Shenick Island [of heart attack, acc. to coroner’s report]; The Poetical Works of Thomas MacDonagh, posthumously published Sept. 1916; Literature in Ireland (1916), also issued posthumously; in it he identifies ‘the Irish mode’ as the prosody of Irish-English brought about by the influence of Irish language, and described the aspiration for national independence as ‘the supreme song of victory on the dying lips of martyrs’; P. S. O’Hegarty prepared a bibliography in 1934 which identifies MacDonagh’s translations of Padraic Mac Piarais’s (Pearse) poems into English. NCBE DIB DIW DIH DIL KUN DBIV FDA HAM OCIL |

|

|

| Marriage portrait (1912) | Muriel, Thomas and Donagh (1912) |

[ Click on each image to view it enlarged and in a separate window ]

[ top ]

Works| Poetry |

|

| Plays |

|

| Prose |

|

|

Bibliographical details

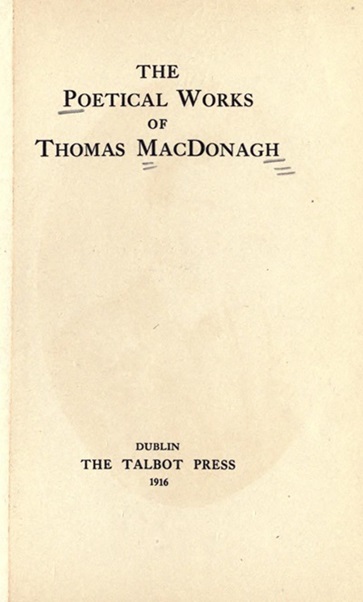

The Poetical Works of Thomas MacDonagh, with a preface by James Stephens (Dublin: Talbot Press; London: Unwin 1916), xii [Stephens, Pref., ix-xii; dated 10 August 1916], 168pp. CONTENTS: Songs of myself; Lyrical poems; The book of images; Translations; Early poems; Inscriptions; Miscellaneous poems. Availability: Copy of 1st edn. held in Calfornian U. Libraries available at Internet Archive - online; Do. [another imp.] (Talbot Press 1919) held at Amarsingh College, Sringhar, scanned at Allama Iqbal Library, Univ. of Kashmir - available online].

The Poetical Works of Thomas MacDonagh (Dublin: Talbot Press 1916) See Contents (poem titles) - attached; also Preface by James Stephens - infra.

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

[ top ]

Commentary

See separate file -as infra.

[ top ]

Quotations

“The Yellow Bittern” (trans. of An Bonnán Buí by Cathal Buí Mac Giolla Ghunna c 1680-1756): ‘The yellow bittern that never broke out / In a drinking bout might as well have drunk; / His bones are thrown on a naked stone / Where he lived alone like a hermit monk. / O yellow bittern! I pity your lot, / Though they say that a sot like myself is curst - / I was sober a while, but I’ll drink and be wise, / For I fear I should die in the end of thirst.’ (For full text, see infra.)

‘Speech-verse has its origin in human speech as distinguished from song. It is a development of speech through oratory and the like, not from or through vocal music.’ (Thomas Campion and the Art of English Poetry [by] Thomas MacDonagh, MA (Dublin: Talbot Press 1913, p.46.)

Literature in Ireland (1916): ‘These studies are then a first attempt to find standards for criticism in Irish and Anglo-Irish literature, more especially in Anglo-Irish poetry’ (p.19); ‘the literature produced in the Engish language in Ireland during the nineteenth century had no such rights of succession to previous epochs of English literature as had the work of Dryden to the work of Ben Jonson ...’ (pp.21-22); ‘Anglo-Irish literature is then different in its origins, in its history, in its tradition, from Scots. At its weakest and poorest it is a weak and poor imitation of the weak and poor contemporary work of Englishmen. At its richest and strongest it has qualities of its own not to be found in the work of any Englishmen of the time. And it is distinctly a new literature, the first expresssion of the life and ways of thought of a new people, hitherto without literary expression, differing from English literature of all periods not with the difference of age but with the difference of race and nationality.’ (p.23.) ‘[Anglo-Irish literature not possible until] the people whose life was the subject matter [...] spoke the English language and spoke it well, and when Irish writers had attained what may be called the plenary use of the English language ... when, in a word, Irish writers and Irish readers were able to practise and appreciate the art of English poetry and the art of English prose.’ (p.24.) [Cont.]

Literature in Ireland (1916) - cont.: defines Anglo-Irish literature as that ‘produced by an English-speaking Irish, and by these in general only when writing in Ireland and for Irish people’ (28); ‘[T]he literature of a dialect is tuneful only to the accompaniment of a central literature’ (p.31); ‘one of the distinctions of Anglo-Irish literature that marks it off from the mere epochs of English literature is its independence of obsolete species’ (p.34); ‘In spite of the self-consciousness of the age, in spite of the world influences felt here, in spite of all our criticism, the Irish poets and writers (those who are truly Anglo-Irish) are beginning all over again in the alien tongue that they know now as their mother tongue’ (35); ‘the things that have affected English literature most powerfully affect our literature. Indeed it has its beginnings partly in the Romantic Revival’ (p.36;the foregoing cited in Chris Corr, ‘English Literary Culture and Irish Literary Revival’, PhD Thesis, UUC 1995). [Cont.]

Literature in Ireland (1916; 1996 facs. rep.): ‘One influence of Irish remains to be noted, perhaps the most important of all with regard to poetry, the effect of Irish rhythms, itself influenced by Irish music, on the rhythms of Anglo-Irish poetry. English hythm is governed by stress. In England the tendency is to hammer the stressed syllables and to slur the unstressed syllables. In Ireland we keep by comparison uniform stress. A child in Cork reading the word unintelligibility, pronounces all the eight syllables distinctly without special stress on any, though his voice rises and falls in a kind of tune or croon, going high upon the final syllable. / Early Irish verse is syllabic. The lines are measured by the number of syllables. / In modern verse, both Irish and English, the lines are measured by the feet, and commonly the feet differ from one another in matter of syllables: each foot has one stressed syllable. In common English verse the voice goes from stress to stress, hammering the stress. / In most Anglo-Irish verse the stresses are not so strongly marked; the unstressed syllables are more fully pronounced; the whole effect is different.’ (p.36.) [Cont.]

Literature in Ireland (1916) - cont. [sundry citations]: ‘It is well to let it be known that some of the studies [in Literature and Ireland] were written before the summer of 1914. The present European wars have altered our outlook on many thing[s], but as they have not altered the truth or the probability of what I have written here, I have not altered my words. I will be seen, I anticipated turbulence and change in the arts. These wars and their sequel may turn literature definitely into ways towards which I looked, confirming the promise of our high destiny here.’ (Ireland in Literature [.... &c.], 1916; quoted in Gerald Dawe, Introduction to rep. edn. as printed in Causeway, Autumn 1996, p.59.)

On language: ‘A language that transmits its literature mainly by oral tradition cannot, if spoken only by thousands, bequeath as much posterity as if spoken by millions. The loss of idiom and of literature is a disaster. But, on the other hand, the abandonment has broken a tradition of pedantry and barren conventions; and sincerity gains thereby.’ (Excerpt in FDA2, p.994.)

[Literature in Ireland, 1916 - further.] ‘We have now so well mastered this language of our adoption that we use it with a freshness and power that the English of these days rarely have. […; 169] The loss of [Gaelic] idiom and of literature is a disaster. But, on the other hand, that abandonment has broke a tradition of pedantry and barren conventions; and sincerity gains thereby. […] Let us postulate continuity, but continuity in the true way.’ (Ibid., 1916, pp.169-70; cited in Gerry Smyth, Decolonisation and Criticism: The Construction of Irish Literature, London: Pluto Press 1998, p.82; also [in part] in Aaron Kelly, Twentieth-Century Literature in Ireland: A Reader’s Guide to Essential Criticism, London: Palgrave Macmillan 2008, p.30 [citing Ibid., 1916, p.169.) “I have little sympathy with the criticism that marks off subtle qualities in literature as altogether racial, that refuses to admit natural exceptions in such a naturally exceptional thing as high literature, attributing only the central body to the national genius, the marginal positions to this alien strain or that.” (Ibid., p.57; quoted in Aaron Kelly, op. cit. 2008, p.29.)

Last words: Mary Ryan, one of his last visitors, reported that ‘his last words aside from prayers were “God Save Ireland”.’ (Quoted in Richard Kearney, ‘Myth and Terror’, in The Crane Bag, 2, 1 & 2, 1978, pp.273-87: p.277.)

[ top ]

References

D. E. S. Maxwell, Modern Irish Drama 1891-1980 (Cambridge UP 1984), cites When the Dawn Comes, as being bound with Seamus

O’Kelly’s The Shuiler’s Child (Maunsel 1908).

|

| Last letter and testament of Thomas MacDonagh |

|

MacDonagh also reiterated his motive - being, ‘the love of my country [and] the desire to make her a sovereign independent state.’ - along with his wishes regarding his estate. |

| [Posted by Geraldine O’Sullivan on Facebook 15 April 2016]. |

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, selects “In Absence”, “After a Year”, “In an Island”, “Two Songs from the Irish”, all from Songs of Myself; also “The Night Hunt, “Wishes for My Son”, and “The Yellow Bittern”, from Lyrical Poems [752-55]; also extracts from Literature in Ireland (1916) [989-94]; further, citations at 286 [Seamus Deane, ed., provides note on Eoin MacNeill’s ‘The North Began’ (1913), incl. passing reference to MacDonagh, viz., ‘at first the IRB had 12 members in the provisional committee, of thirty ... by the autumn of 1914, by which time three of the future leaders of the 1916 Rebellion - Pearse, MacDonagh, Plunkett - had joined the IRB - the IRB was in a position to take over the leadership of the Irish Volunteers]; 367 [dedicated Literature in Ireland (1916) to Sigerson]; 722-23 [Deane, ed., writes regarding 1916 poet-patriots: ‘Their work has something adolescent and autodidactic; they are writing out of an idea of poetry that they have created for themselves out of very little. MacDonagh’s MA thesis on the Elizabethan poet Thomas Campion [exemplifies] this assertiveness, with its ultimately touching faith in upper-case abstractions - Poetry, Faith, Beauty, Love and all the numinous gods and goddesses of the temple dedicated to Ireland ... according to MacDonagh in his thesis and his posthumously published Literature in Ireland, it is possible to divide English verse into [...] speech-verse and song-verse and to identify a specifically ‘Irish mode’ as that ‘of a people to whom the ideal, the spiritual, the mystic are the true’ [… &c; with rem., ‘in spite of Sigerson et al.’] 756 [MacDonagh ‘wavers between “Celtic” and “Gaelic” determinations of the nature of Irish poetry [but finally] offers the hope that Irish poetry in English might bear witness to its dual heritage ... MacDonagh’s critical writing is an abortive attempt to absorb Sigerson’s wide tolerance [with a rudimentary theory]’; 774 [Seamus O’Sullivan, “Dublin (1916)” [‘... the absent faces ... Thomas MacDonagh’s laughing mouth / And eyes of a happy child’],; Francis Ledwidge, “Lament for Thomas MacDonagh” [‘He shall not hear the bittern cry / In the wild sky, where he is lain, / Nor voices of the sweeter birds / Above the wailing of the rain ..’]; 782 [effect of MacDonagh’s execution on Francis Ledwidge]; 807n. [references in Yeats’s “Easter 1916” (‘... I write it out in a verse- / MacDonagh and MacBride ...’) and in his “Sixteen Dead Men” (‘You say that we should still the land / Till Germany’s overcome / But who is there to argue that / Now Pearse is deaf and dumb? / And is their logic to outweigh / MacDonagh’s bony thumb?’)]; 1008 [Luke Gibbon, ed., on MacDonagh with Aodh de Blacam as countervalent voice to Corkery’s attempt to expunge the Anglo-Irish from the Irish literary canon]; [contemp. biogs., ?1019]; [bibl. 1020, see 780]. See also The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing(1991), Vol. 3, 130 [taught Austin Clarke (his successor) at UCD]; 492 [Deane, ed. notes that MacDonagh tried to formulate alternative definition of Irish literature to Yeats’s]; 497-99 [extract from Austin Clarke, A Penny in the Clouds, Chp. 3.iii, relates his meeting with MacDonagh in his house on Oakley Road, having written a sonnet MacDonagh liked; in UCD he was to be seen walking, ‘as small as Thomas Moore, and as curly-headed, speaking vivaciously with quick gestures’; he opines, ‘A lyric comes suddenly with a lilt or a verbal tune, ... But you may often have to wait for months until the words come’; he was certain that Campion was of Irish descent ... formerly pronounced Champion (i.e., Cruaidhloach/O’Crowley) ... his theory of song-verse and speech-verse ... [and at lectures] his theory of the Irish Mode [...]; “Who are the swine?” ... suddenly, one day, during a lecture on the Young Ireland Poets, he took a large revolver from his pocket and laid it on the desk, “Ireland can only win freedom by force”, he remarked as if to himself]; 508 [goes with Bulmer Hobson to McNeill’s house on Good Friday, 1916]; 562-3 [Luke Gibbon, ed., comments that MacDonagh was representative of nationalism but part of a current that sought to distance itself from racial distinctions; quotes from Literature in Ireland, 1916: ‘I have little sympathy with the criticism that marks off subtle qualities in literature as altogether racial, that refuses to admit natural exceptions in such a naturally exceptional thing as high literature, attributing only the central body to the national genius, the marginal portions to this alien strain or that’; MacDonagh’s replacement of Matthew Arnold’s “Celtic note” by what he called “the Irish mode” derived partly from his distrust of racial theories]; [563n.[ his critical writings badly served by commentators; cites Robert Lynd (op. cit, 1919), and Declan Kiberd (opo. cit. 1979), for perceptive discussion]; 566, 568 [Gibbons writes that MacDonagh was posthumously conscripted into the ranks of those nationalists who looked to messianism ... ill at ease with such messianic sentiments ... principal speaker at meeting on Ireland, Women and War (Dec. 1914), expressing revulsion against bloodshed; yet for F. S. L. Lyons (Culture and Anarchy 1890-1939) there was ‘a clear indication that both Plunkett and MacDonagh were already imbued with the doctrine of blood sacrifice’ before the Rising]; 734 [saw in discontinuity a dynamic form of cultural change [ed.], 588n, signatory to the 1916 Proclamation]; 816 [Eoghan Ó hAnluain, ed., writes that MacDonagh recognised Pearse’s as first competent contemporary Gaelic poet]; 887 [MacDonagh’s trans. of Pearse’s ‘Fornocht do Chonac Thú’ appeared in Literature in Ireland (1916)]; 1024 [executed 3 May]; 1309 [representative of Gaelic revival without the Pearsean ‘Celt’].

Booksellers (in 1997): HYLAND, No. 220 (1996), lists Last and Inspiring Address ... before a Court Martial, after sentence of death had been pronounced; single sheet, one side 21x25mm. DE BURCA, Cat. No. 18, lists Lyrical Poems (Dublin, The Irish Review 1913); limited to 500 copies; ed. Irish Review. 1916 signatory.

Belfast Central Library holds Literature in Ireland (1916); Poetical Works (1916); Songs of Myself (1910), and [?] Pagans (1920).

[ top ]

Notes

Freeman’s Journal, review of When the Dawn is Come (Oct. 1908), supplies account of a well-filled house and further details, viz., the play concerns an Irish insurrectionary army in the field; contrast[ing] views of old man and young man upon terms of peace; same scene for three acts; ‘considerable ingenuity has been displayed in developing a complicated story within this irksome limitation, but “excursions and alarms” are frequent’; ‘three characters stand out’, viz, Turlough, the man of brain [‘the thinker forced by circumstance to be resolute for once’]; O’Sullivan, the man of action,; and Ita, ‘one of the ladies of the council who loves Turlough, and being in his confidence, nearly shares his fate’; ‘a few of the long orations might be usefully condensed ... these are the only criticisms ... epoch-making success ... above average both in idea and workmanship ..’. Padraic Colum reviewed for Sinn Féin, with reservations [‘reticent when he should be explanatory ... the dialogue not of properly the stage’]; “HSD” in Dublin Evening Mail was sterner: ‘All the dialogue is vapid ... it is not drama’ (Quoted in Robert Hogan & James Kilroy, The Abbey Theatre: The Years of Synge, 1905-1909, Dublin: Dolmen 1978, p.227-29 [copy supplied by Christopher Murray].

Romantic Ireland?: Mary Colum gives the following account of MacDonagh’s marriage proposal: ‘He called at my little flat, armed with an engagement ring, and told me in a very caveman manner that he had arranged everything, that I was to marry him on a certain date in a certain church, and that I had better accept my destiny. The argument that ensued reduced me to such a state of panic as I had never known, for I was afraid I might be unable to hold out, especially as he said I had encouraged him and ought to have some sense of responsibility about it. But I managed to be strong-minded, and the harassing interview ended with tears on both sides, with his throwing the ring into the fire and leaving in a high state of emotion.’ ( Life and the Dream, London: Macmillan 1947, p.175; cited by Taura Napier, ‘The Mosaic “I”: Mary Colum and Modern Irish Autobiography’, in Irish University Review, 28, 1, Spring/Summer 1998, p.46.)

Celtic prosody: ‘Too much can be made of the metres’ (of Gaelic poetry); comment from Anglo-Irish Literature (1916), cited by Kevin Kiely, reviewing reprint in Books Ireland (Feb.1 996), p.20.

Elegies to MacDonagh incl. Francis Ledwidge’s ‘Lament for Thomas MacDonagh [‘He shall not hear the bittern cry ...’], as well as his place in Yeats’s 1916 poems, and an elegy by Dora Sigerson Shorter in The Tricolour (1922) [viz., ‘They Did Not See Thy Face, in Memory of Thomas MacDonagh’].

Joseph Plunkett: For MacDonagh’s association with Joe Plunkett, as recounted by his sister Geraldine Dillon (in Dublin Magazine, Spring 1966), see Joseph Mary Plunkett - as infra. See also Robert Lynd, for use of Literature in Ireland in Ireland a Nation (1919) - as infra.

Austin Clarke wrote of MacDonagh: ‘Students watch their lecturers with close attention, so it was that late in the Spring of 1916, I began to realise, with a feeling of foreboding, that something was about to happen for I noticed at times, though only for a few seconds, how abstracted and worried Thomas MacDonagh looked. Suddenly one day, during a lecture on the Young Ireland poets, he took a large revolver from his pocket and laid it on the desk, “Ireland can only win freedom by force”, he remarked as if to himself.’ (Clarke, A Penny in the Clouds, 1968, Chp. 3. iii; p.35; cited in The Heart Grown Brutal: The Irish Revolution in Literature from Parnell to the Death of W. B. Yeats, 1891-1939, Gill & Macmillan 1977, p.84.)

Seamus Heaney, ‘In his [ MacDonagh’s] view the distinctive note in Irish poetry is struck when the rhythms and assonances of Gaelic verse insinuate themselves into the texture of English verse. … I am sympathetic to the effects gained but I find the whole enterprise a bit programmatic.’ (Preoccupations, London: Faber & Faber 1980, p.36.)

Sisterhood: A sister of MacDonagh became a nun (Sr. Francesca) and was in attendance at the Cappagh Hospital where Benedict Kiely received treatment for spinal TB. (See further under Kiely, Drink to the Bird, London: Methuen 1991 [as infra].)

Thomas MacDonagh Memorial Hall Appeal is a 1-page bi-lingual pamphlet appealing for subscriptions to a fund aimed at the created of a hall of that name in Cloughjordan, close to MacDonagh’s home. (See William O’Brien Collection of National Library of Ireland [album], Cat. LO P115, Item 50.)

Francis Ledwidge: Ledwidge’s famous elegy for Thomas MacDonagh (‘He shall not hear the bittern cry ...’; as infra) survives in three manuscript copies. One, given by Lord Dunsany to MacDonagh’s son Donagh, is considered authoritative and is held in the National Library of Ireland. Another, presumably original, version being written on tissue paper, is now held by the Royal Irish Academy. A third, which came up for auction in March 2018, was given by Ledwidge to a young woman serving as cook at Ebrington Barracks in Derry/Londonderry in late 1916 when he was recovering from wounds. The MSS is written on a florally-decorated single sheet in Valentine-card style and was clearly intended as a love-token. The name of he recipient is unknown or else undisclosed by the auctioneers. This version contains several variations from the final, received text including the lines “the wide sky where he is lain” for “the wild sky where he is lain” and “perhaps he’ll hear her low at morn/Deep as the knee in pleasant meads” for “perhaps he’ll hear her low at morn/lifting her horn in pleasant meads”. The MSS is also adorned with an illustration of Chocolate Hill, a Turkish redoubt which was stormed by Ledwidge’s regiment, the 5th Battalion of the Inniskilings at Gallipoli. Taken in conjunction with the far-away place indicated by the opening lines, this suggests that the poem may have been written for the dead of that ill-fated campaign and only adapted to the case of Thomas MacDonagh on hearing the fell news. The MSS was offered by Bonhams in London for £12,000-18,000 and sold at £16,250 inc. premium. (See Ronan McGreevy, Irish Times, 11 Mar. 2018 - online. [Note: the article includes a photo of the manuscript.)

[ top ]