Life

| 1930- ; b. 7 July 1930 in Glasgow, where his family lived until outbreak WWII; his gf. owned a 20-acre farm nr. Shercock; and became a successful publican and hotelier in Scotland who later bought a farm in Monaghan on the advice of a local priest (to prevent its reversion to Protestant owners); was first sent to St. Andrews, a Benedictine Prep School in Edinburgh; afterwards at Castleknock College (Dublin) and in UCC [Cork], his holidays were spent in Clones, where he remained in Ireland during the war, being ed. at Killashee, Co. Kildare, Castleknock College, Co. Dublin, and University College, Cork (grad. BA in English & History); |

| published story in Irish Writing, 1940, and invited by London publisher Rupert Hart-Davis to submit a novel, leading to discovery that he could write dialogue but not as yet to book-publication; m. Margot Bowen; farmed first in Wicklow, then in 1954 at Drumard House, taking over family farm nr. Clones, Co. Monaghan (purchased by his gf.), located 400 yards from the border - and where he continued till his death in 2022; started writing in 1962 and called himself ‘a farmer who happens to write, or a writer who happens to farm’; sent first play, A Matter of Conscience, to Hilton Edwards at the Gate in 1959; shared critical honours with Brian Friel at Dublin Theatre Festival, 1964 with King of the Castle (revived 14 Sept. 1970, and again in 1989, dir. Garry Hynes [60th anniv. of Dublin Th. Fest.), the story of an impotent elderly farmer in Leitirm called “Scober’ McAdam, who gets a young drifter (Matt Lynch) to impregnate his wife, based on a story gleaned from a clergyman, produced at the Dublin Theatre Festival; involved in writing The Riordans in the 1960s; wrote Pull Down a Horseman (1966; pub. 1979), play dealing with career of James Connolly and produced as part of the 1916 commemorations; Breakdown (1967); |

| wrote Swift (1969), a play on Jonathan Swift, which failed at the Abbey; also plays for television Breakdown; Some Women of the Island; A Matter of Conscience; The Funeral; RTÉ screened Victims, ‘a trilogy dealing with contemporary Ulster’, being a novella with the additional stories ‘Cancer” and “Heritage”; adapted Thomas Flanagan’s The Year of the French serialised on RTÉ / Channel 4, 1979; wrote Gale Day (1979) commissioned by the Abbey and RTÉ at centenary of Patrick Pearse’s birth; issued Death and Nightingales (1992) a tragic pastoral novel set in 1883, in the wake of the Invincibles, and based on a real events - ‘a tale from across the lake’ (interview, infra); his play Pull Down a Horseman was stage in Aras an Uachtarain in Feb. 2016 in the presence of President Higgins; published “Heaven Lies About Us” (2004) - a collection of short stories written over several years, the title-story being a tale of brother-sister incest-abuse, written in 1997; issued Tales from the Poor House (1998), four dramatic monologues set in Famine Ireland, commissioned and screened in Irish and English versions on RTÉ/TnaG; |

| winner of the Hubert Butler Award for Prose from Irish Cultural Institute, 2002; issue Heaven Lies About Us (2005), collected shorter fiction; winner of the AWB Vincent Literary Award, 2006 and won an Irish Life Award at the Dublin Th. Festival; issued The Love of Sisters (2009), a novella focussed on the relations of Carmel Carmody, a Carmelite who leaves her order, and her sister Tricia with whom she stays and who betrays her with man that Carmel marries, a handsome but morally dubious Cavan undertaking, himself a cousin; wrote a letter to The Irish Times defending Dermot Healy’s Long Time, No See against the reviewer Eileen Battersby, 29 March 2011 [see infra], and was answered by several others supporting Battersby’s verdict; he read “Come Dance with Kitty Stobling” by Patrick Kavanagh at Kavanagh’s graveside in Inniskeen, Co Monaghan in 2017; d. [26] August 2027; ashes spread in 7th c. Celtic church hear Drumard; survived by his wife Margot [née Bowen], with whom four chilren [Ruth (actress under family name), Marcus, Patrick and Steven). DIW DIL FDA OCIL |

|

|

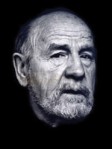

| Photos by Pat Langan and Bobbie Hanvey (printed in The Irish Times, Aug. 27 2020). [Click to enlarge.] |

|

[ top ]

Works| Drama |

|

| Short fiction |

|

| Novels |

|

| For children |

|

| Collected works |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

| Occasional |

| “For Margot Bowen” [poem], in The Irish Times (10 Nov. 2000), Weekend p.11 [‘Let’s ignore the curlew’s lament nor mind / The brown hawk circling high above the wood …’]. |

Bibliographical details

Heaven Lies About Us (London: Jonathan Cape; Australia & NZ: Random House 2005), [8], 309pp., ill. [port. on back cover verso]. Contents, “Heaven Lies About Us” [1]1996; “Truth” [35] 1985; “Victorian Fields” [45]; “Roma” [57]; “Music at Annahullion” [63] 1985; “Cancer” [75]; “Heritage” [87]; “Victims” [141] 1985; “The Orphan” [221]; “The Master” [239]; “The Landlord” [267]; “The Mother” [295-309] 1985; Arranged chron. in order of first publication; copyrights stated as above on t.p. verso. Ded. “For Margot for a lifetime”.

[ top ]

Criticism

|

See also D. L. Kirkpatrick, Modern Dramatists (London: St. James Press 1988), pp.350-51, and sundry reviews under Commentary, infra. |

[ top ]

| Some short crits ... |

| Michael Ondaatje: ‘A deeply moving, powerful, and unforgettable tale.’ |

| John Banville ‘One of the masterpieces of late twentieth-century Irish writing’ - New Yorker. |

| Colm Tóibín: ‘clearly one of the great Irish masterpieces of the century’] |

| —all quoted on inside cover of Heaven Lies Around Us (pb. edn., 2005). |

| Alan Warner: ‘The greatest living Irish prose writer [...] One day, great twentieth-century prose in the English language will be acknowledged to include Eugene McCabe’s breathtaking facility and the deep, necessary anguish of his fictional universe.’ (Inside cover of Heaven Lies Around Us, pb. edn., 2005.) |

Colm Tóibín, Walking the Border (Macdonald 1987), photos by Tony O’Shea, ‘The Walls of Derry’ [Chap. 8], Tóibín meets McCabe and his wife Margot at their house, Dromard, Co. Fermanagh, the farm straddling the border near Lackey Bridge, closed; McCabe talks about the targeting of the UDR and RUC which is experienced by the Protestant locals as genocide; the chapter includes an account of the genesis of his two books published in the 1970s, Victims (1976) and Heritage (1978); got the idea for Heritage from a woman living in the abandoned house at Lackey Bridge who also cleaned in Dromard; also worked across the border for the Johnston; she mentioned that there was friction in the household because a son Ernest had joined the UDR; Tóibín cites the opening of the story, and ends recounting how the McCabe’s heard shooting one night, Sept. 1980, and learnt the following morning that Ernest Johnston had been shot dead; they listen to the car radio appalled; the character in Heritage had been shot dead; now the original had been shot dead as well.’ (pp.107-110). [Note: Tóibín’s remark that McCabe only writes masterpieces is often quoted.]

Carlo Gèbler, review of Death and Nightingales, in The Spark, 3 March 1992, pp.48-49: Gèbler discusses the traditional Irish distinction between domestic violence and political violence (traditionally considered justifiable) in relation to the crimes of Liam Ward, Gebler says, ‘As it is the same sensibility that is at work in both cases, then one can no longer argue that there is a qualitative distinction between the two kinds of violence ... if the revolutionaries of the past are no longer gods, then it is no longer possible to justify emulating their deeds in the name of a continuing national liberation struggle.’

Carlo Gèbler, review of Death and Nightingales in Fortnight (Nov. 1992), [q.p.]; set at the time of the Phoenix Park Murders. Liam Ward, quarryman and Fenian, plans to elope with Beth, the daughter of a Protestant quarry owner, though herself a Catholic as a result of her parents mixed marriage. They [plan to] murder her father for his gold, kept in the house [a safe]. Ward however pursued by the Fenians whose funds he has stolen, and it turns out that he plans to murder Beth too, once the money is secured [with a half-witted accomplice]. McCabe equates Fenianism with duplicity and unscrupulous killing; ‘a fine, iconoclastic book’. Further: battered by her father, Beth faces him, deceives him into rowing to a lake-island (her island) and pulls the plug from the boat; he cannot swim. A kind of reunion of daughter and father occurs, revolving round the fact that he has always reviled her as the daughter of his Catholic wife conceived before his marriage to her; her mother has been gored to death by a bull with his son in her womb.

Simion D. [pseud.], ‘“This Place Owns Me”: Eugene McCabe in Conversation with Simion D’, in Irish Studies Review, 7 (Summer 1994), pp.28-30: [...] “McCabe’s fictional space cannot be separated from the real geographic locations: Ulster, Fermanagh and Monaghan mainly. “This is my universe because I’ve been here since I was ten. In writing you describe what you see.” I point at the fact that he was born in Glasgow in 1930 of Irish parents, and was educated in Dublin and Cork. I detected only one short story, “Truth”, set somewhere other than Ulster. “It is this place that has me by the short and curlier’, he confesses. “I went as a writer in residence to Glasgow for a period of six months, over the winter. I could have stayed there ... I came back and continued farming. My God, I was glad to be back!”

[Interview with Simion D. - cont:] The moody April has chosen a mild twilight for this second meeting of ours. Inviting to recollection. To nostalgia. “It was in the month of May’, he goes on. “I didn’t realise, when I was away, how much I missed it.” / Nostalgia for a faraway place is common, but it is nostalgia for living and working in the place he loves that makes me identify with Eugene McCabe - the writer and the space, his space, a strong relationship, not always an easy one but deep, essential, just like the fundamental feelings that rule his writings. He could go and live somewhere else, “by the sea or outside Dublin”. “It wouldn’t have to be the anxiety of the land, because there is an anxiety.” On the other hand, maybe the land, maybe living here, working here, did compensate for the take-up that I didn’t produce the books I wanted to produce”. The places have their tales and histories, the writer puts them down. “Music at Annahullion” is based on what happened “a few miles from here, across the river’; Death and Nightingales is the literary re-working of “a tale from across the lake”.

[Interview with Simion D. - cont:] McCabe’s routes in life appear like circles starting and ending at Drumard. Most of his short stories, his latest novel too, have a circular construction. An ordinary or extraordinary event, emotion or thought, sets the characters in motion. A catalyst - fundamental feelings, tribalism, politics - determines development and fate. This is all on the background of a space which is always there, always the same, as eternal to us as the cosmic elements. “This place owns me’, he says. “It has its tentacles round me, round my heart, my brain, my blood. It’s like a woman!” / McCabe’s Ulster is Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha, Steinbeck’s Pastures of Heaven, Joyce’s Dublin, Marquez’s Macondo. Always present in two dimensions: the real and the fictional. Had it not existed, I’m sure McCabe would have invented it.” (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

[ top ]

Eileen Battersby, ‘Powerful polemics motivated by injustice [...]’, review of Heaven Lies About Us, in The Irish Times, Weekend (15 Jan. 2005), p.13: ‘Returning to these stories has proved problematic. They read less as narratives than as bulletins, deliberate snapshots chronicling the woes of a borderland country in turmoil. Collectively they share anger and rage. McCabe is far less interested in individuals and the heroic than is his near-contemporary, William Trevor, who is more drawn to the private than the public. If memory and nuance inspire Trevor, McCabe’s preoccupation with history is far more polemical. / His Ireland is a bleak hell of angry sex and tribal hatreds. There are few moments of tenderness, and little humour. The only humanity gracing these stories is that which McCabe confers on Harriet, the despairing hostage truth-teller in ‘Victims’. While her responses, filtered through her wealth, privilege and reading of poets, are sophisticatedly despairing, there is a sole idealist, Mickey, the old down-and-out dreamer in ‘Roma’. Having allowed his existence to revolve around the purity of a young girl, he is devastated to discover her sexual curiosity is as earthy as that of her peers. / Even the descriptions of the Border county landscape present throughout the stories has a tight-lipped clarity. McCabe is no romantic; he is a realist merely based in a pastoral setting. His realism is brutal and often melodramatic. Sex decides, and it is the furtive, impersonal sexuality of barter, fear and shame. / Much of the dialogue, clipped and raw, would probably convince better on the stage, supported by gesture and long silences, than it does on the page. As early as the opening title story, McCabe makes his intentions clear. This is a story of abuse.’ (See full text in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews” - as attached.)

John Kenny [short notice], in The Irish Times (25 Feb. 2006): ‘McCabe explores the primitive forces that can explode within private and public lives, and by the end the title assumes a formidable double meaning. Humans are vicious, anguished, potentially unredeemable, and our idea of heaven may be a lie about us.’

John Kenny, ‘A Tale of Cloister and Heart’, review of The Love of Sisters by Eugene McCabe, in The Irish Times (14 March 2009), Weekend, p.10: ‘[...] Defying received wisdom about the novella’s inability to convincingly treat with time, within the first three pages here we have been skilfully moved from 1947 and the death near Cork of the mother of young Tricia and Carmel Carmody, to 26 years later when Carmel has left her beloved Carmelite order because of the “scruples” it will be the story’s function to uncover. Tricia, whose own intervening life is subtly delineated, insists that Carmel come to live in Spanish Point with her and her daughter, Isabel. Thereafter, with a smoothness and occasional subplotting that are extraordinary for a novella, the narrative moves back and forth in time to recount Carmel’s experiences as a novice and contemplative, her relationships with her fellow sisters (especially the gardener, Martha), her unsure re-entry into life and love outside the convent, and her eventual marriage to a Cavan undertaker which culminates in a hard lesson involving her biological sister. [... &c.’; for full text, see RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.]

Rory Brennan, ‘The Brink of Terror’, review of The Love of Sisters, in Books Ireland (Sept. 2009), p.174f.: ‘Two sisters are neglected in early childhood by their father after the death of their mother. The father takes to drink and is witnessed in flagrante with a babysitter. They are rescued and raised by rich relations who in turn die young. One sister marries and divorces in London, the other enters a convent. The London sister returns home, the professed nun leaves after a postulant is suddenly expelled for having a crush on her. The sisters live together for a while, one quite boozy and sexually active, the other still pious and moralistic. The ex-nun finds work in the home of a widowed undertaker cousin in Cavan, helping with his child, &c. She marries him, even after learning that he wears clothes he has filched from corpses. Both sisters are attractive in personality and physique. The undertaker is not a likeable character but is recorded as handsome. The catharsis comes when the ex-nun discovers her husband in bed with her sister. As in so much of Eugene McCabe’s work the unthinkable and unendurable inexorably happens. The scene is handled with great subtlety and persuasiveness. It is just this capacity to take the reader to the brink of horror and then to somehow leap into the unbridgeable and unbearable that makes him such a marvellous writer. This skill is connected to the dramatic but reaches far beyond it. It would seem from the gesture of a child at the end that that the story points the way to forgiveness and reconciliation. A false ending? A close reading of the text (i.e. “clues”) leads me to suppose that the betrayal was planned by the divorced sister. There are one or two details in the novella (awful word but then the French conte is not very satisfactory either) that don’t ring quite true. The occupations of court clerk and lecturer in economics can simply not be held together and banks did not sell off their large premises in provincial towns until the amalgamations of the late sixties. / These are tiny flaws in an otherwise near-perfect narrative of insight and observation [...]’ For various responses, see:

| Martin Doyle [Obituary], in The Irish Times (27 Aug. 2020) |

|

|

[ top ]

References

Peter Fallon & Seán Golden, ed., Soft Day: A Miscellany of Contemporary Irish Writing (Dublin: Wolfhound; US: Notre Dame UP 1980), gives extract from King of the Castle.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, gen. ed. (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3, selects from Heritage and Other Stories, ‘Cancer’ [1036-42], relationship between Catholic and Protestant in rural Ulster, Lisnaskea, an IRA atrocity; UDR and Army activity; and memories of the expulsion of the MacMahons by Cromwell; described as ‘ highly gifted, if reluctant, writer’; King of the Castle [1182-86]; BIOG & COMM 1305 [as above]. D. E. S. Maxwell [sect. ed.] calls him a highly gifted if reluctant writer [who] farms the family holding in Co. Monaghan; wrote a trilogy of plays for television under the title Cancer; one section of this was published as a short story [sic], Victims (Mercier / Gollancz 1977). The other two, ‘Cancer’ and ‘Heritage’ appeared as short stories in Heritage and Other Stories (Gollancz 1978).

D. E. S. Maxwell, Modern Irish Drama 1891-1980 (Cambridge UP 1984), ‘His dramatic talent is undeniable, but represented in his more recent work by a trilogy of television plays written for RTE on the Northern Irish troubles’. (pp.169-70.)

Gollancz Ltd. publisher’s notice for Christ in the Fields (1993) avers that ‘Cancer’ appeared in Dublin Magazine, and after in Heritage & Other Stories (London: Gollancz 1978), and that the ‘three tales were conceived as one. this is their first time to be published in one volume.’

Helena Sheehan, Irish Television Drama (RTÉ 1987), lists The Apprentice (1979); Cancer (1973); John Montague, A Change of Management, adapted by McCabe and directed by Jim Fitzgerald (1970); McCabe, The Funeral, dir. by Louis Lenten (1970); McCabe, Gale Day dir. by Pat O’Connor (1979); McCabe, King of the Castle, dir. by Louis Lentin (1977); McCabe, A Matter of Conscience (1962) dir. by Shelah Richards [pp.94, 98]; Brigid K Nalton, Mr Power’s Purchase, adapted by McCabe, dir. by Chloe Gibson (1964); McCabe, Portraits: The Dean [Swift], dir. by Chloe Gibson (1973); McCabe, Roma, dir. by Louis Lentin (1979); with Michael Voysey and Neil Jordan, Sean, dir. by Louis Lentin (1980); McCabe, Some Women on the Island, dir. by Chloe Gibson (1964); McCabe, Victims: Cancer, Heritage, Siege [the trilogy], dir. by Deirdre Friel (1976); McCabe, Winter Music, dir. by Pat O’Connor (1981); Thomas Flanagan, The Year of the French (1982) [6 episodes], adapted by Eugene McCabe and dir. by Michael Garvey [RTE / C4 / FR3]. Also with others scripted The Riordans from 1979.

[ top ]

Quotations

‘Hatred is so sad [...] personal hatred I know only too well, but to hate an entire people, race, sect or class, is so blind, so stupid, so unending, so universal, it makes one despair [...]’ (Lady of big house in Victims; cited in fiction review by Rüdiger Imhof, Linen Hall Review [10, 3], Winter 1993, p.21f.)

“The Mower”: ‘I saw a man upon a sit-upon / Grassing cutting round and round a bungalow. / Three score and ten he was, near Carrigbawn / And thought to myself, pray God I’ll not let go / That way, the glazed eye wide for the end / Letting on to be useful, well knowing / It’s over. With luck they’ll find me tending / Bullocks, saying in the haggard, hoeing / Raspberries in an old garden, upright. / Then I head the finder’s hidden voice: / What mater where you’re found day or night / Alone or in a crowd: you have no choice. / And be forewarned the way I’ll call and geet / I’ll casually nod and tap delete.’ (The Irish Times, 27 May 2000.)

[ top ]

Notes

King of the Castle concerns Scober MacAdam, who has acquired by greed and exploitation a former Big House in Co. Letrim; sexually impotent, and goaded by gossip, he devises a plan to effect the impregnation of his young wife; the play concerns the mutual infliction of wounds by the couple and also the community.

Dermot Bolger remarks on King of of the Castle that ‘Eugene McCabe is - and has always been - a fiercely honest, raw, brutal (in the finest sense), and magnificent writer’ (cited in Dufour 1998 Catalogue in regard to Bolger, ed., Padraic Pearse, Rogha Dánta: Selected Poems, with introduction by Eugene McCabe [pp.7-18] and Iar-fhocal le Michael Davitt [pp.75-79], New Island Books, 1993.)

BBC NI : Eugene McCabe gave an account of the inspiration of the title of his novel Death and Nightingales in an interview on Ulster Radio/BBCNI (Sat. 2 Feb. 1993), in the course of a nature programme.

Victims (1976), The IRA takes a big house family hostage in order to demand the release of prisoners; the IRA family of McAleers is dominated by the mother, ‘an Irish Queen Victoria, with de Valera’s nose and Churchill’s mouth’, and her sons Pascell and Pacelli (Tick and Tock) the bombmakers. Harriet, quizzed at the close by a reporter, declares, ‘The world is still beautiful’. Note: The novel was reviewed by Ben Kiely in The Irish Times (20 Nov. 1976), [q.p.].

Swift, failed in its original 1969 production at the Abbey Theatre, directed by Sir Tyrone Guthrie, with Micheál Mac Liammóir playing Dean Swift. It was sucessfully rewritten in 1972 as an expressionistic study of Swift’s madness.

The Letter: McCabe wrote a letter to The Irish Times on 29 March 2011 defending Dermot Healy’s Long Time, No See against criticism in a review by Eileen Battersby suggesting that (Weekend Review, 26 March 2011), and was answered by several others defending Battersby’s judgement (viz., Darren Reddin of Metro Ireland, and John Sullivan of Saval Park Cresc., Dalkey, Irish Times, 31 March 2011). McCabe characterised the review as ‘stupid’ and drew attention to a ‘ghost story’ by Battersby [3rd para, in seq.]:

Letter to The Irish Times (Irish Times (29 March 2011) Madam, – I have just read Eileen Battersby’s Olympian review of Dermot Healy’s Long Time No See. She presses all the right buttons to show the editor and the reading public how knowledgeable she is to expound on his work. Very professional, well indexed stuff. I have also read it. Clearly we were reading different novels. What does it mean when the subtitle states, “Dermot Healy has written a young man’s novel but its dialogue and observations are far longer than this story justifies”? I hesitate to use the word stupid but that’s how that subtitle strikes me.

Does Ms Battersby look at the photograph of Dermot Healy and say: This is an old man’s effort not fashionable like Neil Jordan’s so I’ll disembowel him because that’s how I feel today?

We were all privileged to read Ms Battersby’s ghost story in The Irish Times Magazine a few months ago. It was a revelation. Sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph, it was the worst piece of creative writing I have ever read in a long life of reading. Truly. Stunningly bad. I have used it in a workshop as an example of how to avoid writing “shite and onions”. That this person has the temerity to sit in negative judgment on one of the great masters of Irish writing should not pass without comment. – Yours, etc.Eugene McCabe,

Drumard, Clones,

Co Monaghan.

| Rachel Finucane (Not Good for My Rage) |

‘[...] I thought his letter was overblown, unfair and a bit cruel—everything the actual review wasn ‘t. Battersby’s review was 1,351 words long and it was no hatchet job. She is obviously familiar with the author’s previous work and there are quite a few compliments for Long Time, No See. Personally, I’ve agonised over reviews because I don’t want to rubbish someone’s hard work. There are redeeming qualities in everything, but when you’re digging haphazardly to find that hidden treasure maybe you’re ignoring the giant, glaring X staring at you=it doesn’t quite work. You have to point out the faults because ignoring them is doing the potential audience a disservice.’ |

| [Available online] |

| Diarmuid Doyle (Wordpress) |

|

| [Availale online] |

Eileen Battersby: McCabe wrote a letter to The Irish Times defending Dermot Healy’s Long Time, No See against the reviewer Eileen Battersby, (29 March 2011) [see supra], and was answered by several others supporting Battersby’s verdictThe ‘story’ by Battersby was later characterised in a notice in the paper as a piece of reportage rather than fiction - a point earlier taken up by the reviewer’s defenders. See also the report of Healy’s own response to the controversy in The Irish Times (1 April 2011), accompanied by photo of Healy and Neil Jordan at the launch of Healy’s novel, and the satirical coverage of the affair in Phoenix (‘Reviewing Eileen Battersby’, 8 April 2001, p.22) - in which her piece is quoted in extract. The Phoenix article also cites McCabe’s remarks on Aosdana in 2001: ‘why would I appy unless I went completely bankrupt?’ - and notes that he did in fact joint Aosdana in 2006. Battersby was supported in the letters column by John Banville protesting against McCabe’s ‘intemperate attack’ and dismissing his letter as ‘ad hominem and scatological assault’. (The Irish Times, 30 March 2011; signed Bachelor’s Walk, Dublin.) Battersby’s ghost story - true or false - is copied at www.boards.ie online - accessed 28.06.2011; see also copy, attached.

[ top ]