Life

1961- [occas. pseud. John Creed]; b. Kilkeel, Co. Down, and later raised at Ravensdale, Co. Louth; the son of lawyer, studied law at TCD; novella The Last of Deeds (1989), short-listed for Irish Times/Aer Lingus Prize 1989; Macauley Fellowship of Irish Literature, 1990; novel Resurrection Man (1994), dealing with the activities of a Shankill Butchers-type Loyalist death-squad in 1970s Belfast; filmed by Marc Evans in 1998 to MacNamee’s screenplay; The Last of Deeds republished together with Love in History (1992), the latter novella set around an American wartime base in Ulster, includes Catholic-boy/Protestant-girl scenario; |

issued Blue Tango (2001), concerning the 1950s murder of the daughter of a judge’s family in Belfast, shortlisted for the Booker Prize and the Irish Times Fiction Award, becoming the subject of vocal objections from supposed spokesmen of the Curran family at a reading for the John Hewitt Summer School (Aug. 2001); lives in Sligo with his wife Marie and their children; McNamee was the inaugural recipient of the Ireland Fund of Monaco Literary Bursary at the Princess Grace Irish Library in March 2001; issued The Ultras (2004), dealing with a Nairac-like story of infiltration and assassination in Northern Ireland; |

| also writes the ‘Jack Valentine’ thrillers and, as John Creed, issued The Sirius Crossing (2002) and The Day of the Dead (2003), an intelligence thriller set in Ireland and America; His story “The Road Wife” was short-listed for the Davy Byrnes Irish Writing Award, 2009 among 800 entries; issued Blue Orchid (2010), concerning the murder of a girl in Newry, an actual event which led to the last hanging in N. Ireland, but introducing the detective Eddie McCrink - who is told that the culprit is ‘the town’s business’; contrib. to Irish writers’ comments on election of Donald Trump (Irish Times, 10 Nov. 2016). BOLG DIL |

|

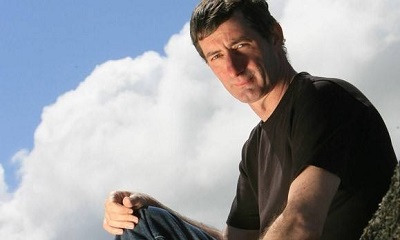

Eoin McNamee, novelist |

| [UCC English Dept. / Autumn Reading series, Oct. 2015.] |

[ top ]

Works| Fiction |

|

| As John Creed |

|

| For children |

|

| Poetry |

|

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

[ top ]

Commentary

John Banville, review of Resurrection Man, in Observer (6 March 1994), [q.p.] remarks that ‘the finest passages ... are the most frightening’.

Robert Winder, [q. title], The Independent (8 April 1994), [q.p.], focuses on Victor’s mother’s saying “It was necessary to have firm beliefs to get by”, [to which McNamee adds] ‘there aren’t many things in the world crueller or more destructive than a firm belief’; reviewer regrets that McNamee didn’t focus more on the ‘sense of enduring sorrow’ associated with this profession.

[q.a.], review of Resurrection Man, in Books Ireland (1994), remarks that Resurrection Man is superior to McNamee’s debut novella, The Last of Deeds and another novella, Love in History (1992).

[q.a.], ‘In Sligo’ [interview], [Young Irish series], BBC Radio 3 Broadcast (5 Oct. 1995): ‘I began to chart a cycle of violence ... it has something to do with sex somehow, and then after sex there is hope, and then hope turns into a sort of despair and then at the tail end of the despair there is violence. At the end of the violence there is sex again.’; further, ‘in Belfast there is a strange geography which is almost an Empire geography - Kashmir Rd., Delhi St., The Holy land, Palestine St., Jerusalem St. - and this whole mapping of Empire. I was trying to work this through the novel, it lends a strange sort of exoticism to the place. I was trying to find a way into this surreal place that Northern Ireland has become, where the perfected electronic surveillance such as the Four Square Laundry, a laundry van which use to go around Belfast driven by British soldiers with two guys with cameras concealed in the roof. The whole gathering of low level intelligence goes on all the time - helicopters with night-sun searchlights - helicopters photographing the streets. What tended to happen with the literature of the place was that people would try to address the whole thing on a moral basis - “isn’t it dreadful” - you had a Catholic shooting a Protestant or a love story across the barricades. It was very worthy but it neither described the place effectively or even really worked in the moral sense.’ [Cited in Robert Goldsmith, ‘The Trouble with Literature’, MA Dipl., UUC, 1996].

Gerry Smyth, The Novel and the Nation: Studies in the New Irish Fiction (London: Pluto Press 1997): ‘“The dynamics of madness” (p.97) comes to replace the normal dynamics of communication and rationality to which even sectarianism nominally subscribes. / But who or what is to blame for all this? The answer, it seems, is the city itself, which “had decided to devise personality for them, assign roles, a script to accompany a season of coming evil”. (p.159) Violence is the condition-zero of the city, its architecture a map of strife and enmity. Naming its streets and estates is part of Kelly’s education into violence, and he is an avid pupil of all the city has to teach him by way of sectarian history. “He felt the city become a diagram of violence centred about him. Victor got a grip on the names.” (p.11) Evil, unchanging and elemental, is built into the architecture and the landscape; according to the moral economy of the novel, Kelly is just more honest than most in his acknowledgement of this. / In a sense, then, the novel is about its own possibility, the possibility of a language that can communicate the reality of politically motivated, savagely executed violence. […] Language, it seems, has taken on a life of its own, exceeding authorial intention. Likewise, once it is introduced into any discourse as a possibility, violence possesses the ability to exceed any ’intention’ couched in political or cultural terms, to take on a life in and for itself. All it needs, the novel suggests, is someone like Kelly to take violence to its extreme, logical end - the logic of random, brutal, indiscriminate chaos. / Sectarianism, then, is just a convenient handle upon which to hang our need for violence, its occasion rather than its cause. Violence is a symptom of life, especially of modern life in which to be human is to be inauthentic, to lack will or agency, to lack, [122] crucially, the ability to change except through ever more fundamental destruction. […]’ (Smyth, op. cit., 1997, pp.121-22.)

[ top ]

Carlo Gébler, review of Eoin McNamee, The Blue Tango (London: Faber & Faber 2001), 270pp., dealing with the murder of Patricia Curran, 13 Nov. 1952, at the grounds of her family home, The Glen, in Whiteabbey, nr. Belfast; dg. of Lancelot Curran, Att.-Gen. of N. Ireland and afterwards Chief Justice; 37 stab wounds; discovered by her br.; Polish soldiers station in the area suspected; interrogation of the family forbidden by Sir Richard Pim, Chief Inspector of Constabulary; charges eventually laid against Iain Hay Gordon, a Scottish national serviceman, who confessed under threats that his homosexuality would be revealed to his mother; pleaded guilty but insane; sent to Holywell Hospital; released after seven years on instructions of Brian Faulkner, Min. of Home Affairs; his sentence quashed in 2000. Gebler notes that the task McNamee sets himself is not to everyone’s taste, particularly as Desmond Curran is still alive, but that McNamee ‘never fumbles’ and that the tale of miscarriage of justice is neither anti-Unionist nor anti-English; calls it an astonishing piece of narrative organisation. As to the real culprit, Gébler notes that Patricia’s effects were not at the scene when she was discovered but were so the morning after, and that Lancelot and Doris knew of her death before her body was discovered; and finally that bloodstains were discovered four years afterwards in a room in The Glen (Irish Times, 7 July 2001, p.14.) Note that McNamee discusses the novel with Gébler at Royal Festival Hall, London, June 11th.

Arminta Wallace, ‘Writing blue murder’, interview with Eoin McNamee, author of The Blue Tango (2001), dealing with the murder of Patricia Curran; quotes the author, ‘To be honest […] what really got me interested in the case was [the] photograph […] reproduced a lot in newspaper articles … If my book is about any one thing … it’s actually about Patricia Curran and who was Patricia Curran. Which means the book is also about woemn and images of women - mothers and daughters and that whole “woman as victim” thing which hangs over certain crimes, that she must have somehow deserved it.’ McNamee recalls that ‘[t]he Tory press in England lost their heads over it [Resurrection Man] - “a poisonous outpouring of anti-Unionist bile by Irish writer Eoin McNamee” - and it was effectively censored out of existence.’ Notes that Desmond Curran, the brother who discovered the body, is a priest in S. African township; Wallace remarks: ‘this tale of large men in suits rallying round to protect their own is unlikely to rehabilitate McNamee in the eyes of the British establishment. (The Irish Times, 23 June 2001, Weekend; for full text, see infra.).

Keith Jeffrey, review of Eoin McNamee, The Blue Tango (London: Faber & Faber 2001), 265pp.: dates murder at 12 Nov. 1952; grounds of home at Whiteabbey, suburb on northern shore of Belfast Lough; finds the characters and context ‘mutable’ - e.g., the location is at one time close to Larne and at another to Bangor; sees it as an application of Flann O’Brien’s principal of metamorphosis in The Third Policeman: ‘Some DMP, it seems, has leaked into Eoin McNamee’s second novel’ [creating] a parallel universe ready to be peopled by fictionalised “real” individuals; generally dismissive of the treatment and the significance of the story. (Times Literary Supplement [Irish issue], 29 June 2001, p.22.)

Margaret Scanlan, ‘Eoin McNamee’s Resurrection Man’ [Chap. 2], in Plotting Terror: Novelists and Terrorists in Contemporary Fiction (Virginia UP 2001), pp.37-58: ‘[...] In Resurrection Man, a 1994 novel about the Northern Irish Troubles, Eoin McNamee also seems to assume the death of the novel as a social force. His writers are two journalists, one dying of cancer and the other drifting into alcoholism; his terrorists are secondary school dropouts, Protestant boys from the Shankill Road. If McNamee’s grim city contains poets delusional enough to consider themselves its unacknowledged legislators, they remain silent. Yet, paradoxically, in this world cut off from high culture, characters close to illiteracy brood over the power of language, and a trained sensitivity to the nuances of public relations rhetoric and an acuteness about the strategies of fictional plotting allow a journalist to predict the course of political events with astonishing accuracy. / McNamee’s novel has a strong postmodern bent, to be detected in the paranoia that informs its plot, in a tone that allows irony to shade into parody and pastiche, and perhaps also in its preoccupation with the images of film and television at the expense of such features of the older realistic novel as fully developed characters and a thoroughgoing interest in history. The application of such techniques to a novel set in the midst of Northern Ireland’s contemporary troubles is surprising, even disturbing, because it forces readers to look at the conflict in a new context. [...].’ (p.37; cont.)

Margaret Scanlan (‘Eoin McNamee’s Resurrection Man’, in Plotting Terror [... &c.], 2001): ‘McNamee suggests, on the contrary, that contemporary Northern Ireland is just as much a part of the global electronic culture as Pynchon’s Los Angeles or, for that matter, Rushdie’s New Delhi. Whatever their origins, the “tribal” hatreds of the North are now modulated through sensibilities shaped by cinematic and televised violence. Irish history, McNamee suggests, is less present to the relatively uneducated foot soldiers in its sectarian wars than America’s mythic urban ganglands and Wild West. Though his story often seems fantastic, it sticks surprisingly close to the documented public record; McNamee never denies the force or reality of public history but instead emphasizes the power of electronically transmitted myths to influence our perceptions of reality and to act on that reality. Northern Ireland as he presents it is a place that confirms the aptness of Baudrillard’s argument about the contemporary electorate: “It is the football match or film or cartoon which serve as models for perception of the political sphere”.. Movies, television, and popular journalism are media through which McNamee’s grim “city” acquires its knowledge of itself; they help it make sense of its violence and its pathologies and direct the actors in its political dramas.’

[ top ]

Shirley Kelly, interview with Eoin McNamee (Books Ireland, Sept. 2001), writes: ‘with Pat McCabe and Colm Tóibín, McNamee had joined a stable of pricey Irish thoroughbred being groomed for international success by Peter Straus at Picador. But while Tóibín and McCabe rose to almost iconic status during the late nineties, McNamee seemed to quit the literary scene altogether.’ Kelly quotes McNamee: ‘I believe that with Resurrection Man, I sort of wrote myself out, exhausted whatever literary resources I had,’ he says. ‘It was a long time before I could find another story that I could stick with for the duration of a novel. It’s not that I’m reluctant to start a new novel, it’s just that if I’m writing without conviction I run out of steam after about twenty pages. But I never stopped writing. I’ve never done anything else really’. Further, on the film of Resurrection Man: ‘The Tory press lined up to take pot-shots at this “poisonous out-pouring of anti-unionist bile“ […It was effectively censored in the North it was shown on only one screen in the entire province.’ Gives account of the case of Patricia Curran: ‘So why, a little after 2 a.m., did the judge ring Patricia’s friend John Steel, who had left her at the bus station that evening, to as if he knew where she might be? And why did McConnell’s boss, Sir Richard Pim, confiscate the telephone records which would provide evidence of this discrepancy.’ Further quotes: ‘I was still writing the book when Gordon’s conviction was overturned […] so I was anxious to portray him in a sympathetic light. He was clearly a scapegoat, suspected of being a homosexual at a time when this was socially unacceptable, so he was particularly vulnerable. All the evidence, the little that was available then and was subsequently uncovered, points to the Curran family, but the [201] were completely overlooked.’

Eileen Battersby, Brief notice in The Irish Times (13 July 2002, Weekend: Paperbacks): ‘[...] Haunting, , dark, graceful, less thriller than elaborate dance of death, this story of losers and liars is based on a real murder and the contradictions that surrounded and continue to surround it. Brilliant use is made of the facts to create an atmosphere of utter ambivalence. The victim, a young girl found dead on the avenue of her magistrate father’s home, has been stabbed 37 times. But when did she die? And where? Set in a 1950s Northern Ireland suspended somewhere between Ireland and England, if closer in mood to a small ruined African colony, it is an extraordinarily well choreographed study of morality, sin, cowardice and failure. At its centre is the angry, wilful victim, herself a mystery. Shadowy yet vivid, she dictates the action, appearing to knowingly court death. Most of the characters, including her father and brother, also have their secrets. It is an unforgettable narrative of flashbacks, doubt and moments of shocking clarity.’

Desmond Traynor, review of The Blue Tango (2001), giving details of plot [as supra] and underlying events adding that a huge bloodstain was discovered in an upstairs room four years after when the house was sold and the carpet lifted. Traynor recognises MacNamee as a ‘true artist’ and remarks: ‘Again, as with his previous book, the prose styule is reminisicent of the lapidary puritan discourse of a morality play, a kind of latter-day Northern Catholic John Bunyan, which is ideally suited to the Manichean societal structures up there. Also striking is McNamee’s sensitivity to language register and its betrayal of social standing, as when some of the statements in the police records by soldiers read more like the product of a well-educated middle-class professional hand. […] the nuances of the social pecking order are perfectly rendered. “Authority“ is one of the most frequently recurring words in the text’ . (Books Ireland, Oct. 2001.)

[ top ]

Róisín Ingle, ‘Body of evidence’, in The Irish Times [Weekend], 20 April 2004): ‘Blair Agnew, the fictional ex-sergeant in The Ultras who is trying to make sense of Nairac’s death in the hope that it will heal some of his own wounds, places the captain at the scene of the Miami Showband Massacre in 1975. Three members of the band were shot by the UVF when their van was stopped at a bogus checkpoint. When, 10 years after Nairac’s death, Ken Livingstone claimed the officer had been involved in the massacre, Nairac’s father, Dr Maurice Nairac (an eye-surgeon), expressed “complete contempt” for the politician. Is McNamee conscious of how the book will be received by the dead man’s family? / “I think about it, but at the same time I feel I am absolutely entitled to examine Nairac and his world and his relationship to the conflict that went on. I don’t feel any qualms about doing it. I think the thing is to do it well. If one is to tell that story at all you have to find a methodology to do it. Is it better to leave it unexamined? I don’t think so. Although I can see from past experience that I am going to take flack from certain sections about The Ultras.”’ [...] Quotes response to film of The Resurrection Man: ‘the film came out, McNamee was accused of being immoral and identifying too closely with the Shankill Butchers, “a poisonous outpouring of anti-unionist bile by Irish writer Eoin McNamee” was how one British newspaper described it.’ ‘Despite her father’s exhaustive investigations into Nairac and his activities, it is she who comes closer than anyone to explaining the British captain: “I can’t help thinking about Robert. I look at his photograph and I look into his eyes. I can’t see anything there”, she writes. “Maybe that is the meaning of the word ultra. That you are ultra secret and do not give anything away no matter what. That they look and look and look and cannot find you. When I was small I hid in the dark and they called but I did not come out. Each to his own, Robert had to learn his own secrets and I had to learn mine, but I think his were about killing people - lots of people - and mine are just sad secrets.” / McNamee has a final word for anyone who might question the morality of his new book. “I always had a quote in my head, I think it is Oscar Wilde, that there is no such thing as a moral or immoral book - there are only good books or bad books. And I am confident this is a good book”.’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

Cal McCrystal, review of The Ultras, in Independent [UK] (2 May 2004). ‘[...] the Nairac story is one of the most abiding and tantalising mysteries to survive the Ulster conflict. / Any attempt to penetrate it entails an encounter with what McNamee describes as “clandestine governance, the dark polity”: collusion between MI5 and the hard men who drink to excess and oil their guns fastidiously, rogue RUC men and others of vaguely fixed affiliations and vaguely directionless intent. In this fictionalised account the reader shares a protagonist’s consciousness “of conspiracy getting out of control ... spiralling downwards”, as MI5 agents strive to undermine peace efforts by MI6. / These events occurred during the most vicious blood-letting by the IRA, and the covert war against the terrorists had become increasingly complex and uncertain. Dirty tricks were the order of the day. These fed into the rumour machine which, in turn, provoked an almost daily dèmenti from the authorities. Nobody believed the denials. Many denied their beliefs. Out from this murk emerges Blair Agnew, a blemished former sergeant of the Royal Ulster Constabulary who has associated with the Ultras. A quarter century after Captain Nairac’s disappearance, Agnew attempts to face up to his own past role in the conflict and to make sense of the Nairac affair, filling his caravan with thousands of newspaper clippings, government statements, secret documents, pictures of dead people, while trying to cope with his anorexic teenage daughter. In McNamee’s electrifying story, the murk thins, thickens, thins again, but never clears.’ [End.] (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

John Burnside, review of Orchid Blue, in The Guardian (20 Nov. 2010): The economy of McNamee’s prose, the way he can use a minor detail or a glib turn of phrase to move us to pity or righteous anger, is equally impressive. He does so much with “the word Ladybird” on a victim’s slip, or the passing description of the flick knife Robert buys with money stolen from his mother’s purse, while his portrayal of vile officialdom – the corrupt but untouchable political fixers; the compromised policeman, in the bosses’ pockets after a sexual indiscretion; the thuggish sergeant who enjoys the casual brutality of his work – is powerfully damning while never straying into sensationalism. / Meanwhile, an atmosphere of dark, damp menace runs through the novel like mildew, an underlying sense of flawed blood and brute superstition that informs every witness statement and every unsound judgment. Robert’s guilt is decided as much by the taint of the places he frequents as by the circumstantial evidence produced in court: the narrative that people construct from tribal memories and fears is, for them, far more decisive than an alibi or a fingerprint. “As in much of the evidence there are other subtle undertones in the policemen’s statement which the prosecution would have been aware of. The fact that Robert had gone to a “semi-derelict house”. The semi-derelict house on the edge of town something which had worked its way into the popular imagination. The dimlit interiors, the rubbish-strewn rooms and the faded wallpapers. People felt that some old magic was at work in them, a watchfulness. Places that were home to half-remembered happenings, folkloric terrors.” That the authorities are quite capable of using those “folkloric terrors” to their own advantage – the minister needs to seem hard on crime, the judge is looking for advancement – comes as no surprise. [...]" (Cont.)

John Burnside, review of Orchid Blue, in The Guardian (20 Nov. 2010) - cont.: ‘What ought to come as a surprise, however, is the way that ordinary people – witnesses, suspects, victims – betray themselves, almost casually playing into the hands of powers that they should be questioning and opposing. These people – the lower classes, the neglected – are, in fact, so desperate to become part of the story that they will accept any role they are offered: “Hesitant at first. Then a story starts to take shape in their heads. They start to see the possibilities of narrative, the interwoven stuff of their lives. How things have shaped themselves around the defining moment ... They try to piece the night together, how seemingly meaningless events become part of the weft. They start to ponder the interrelatedness of things. They are grateful to the interviewer for helping to find the patterns, leading them towards the ornamented telling.” / It is this sense of how the defining moments come to be agreed – of how they are essentially defined by the ruling class – that illuminates Orchid Blue, so that what begins as a crime thriller gradually builds not only into a political novel of the highest order but also that rare phenomenon, a genuinely tragic work of art.’ [End]. (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

Deirdre O’Brien, ‘Singing the Blues’, interview-article with Eoin McNamee, in Verbal Magazine (9 April 2011): ‘[...] The Newry described in the book is a bleak town with many shady characters and its own law for matters such as this. However McNamee isn’t worried about criticism from inhabitants of Newry about his depiction of it. “If you had to answer to the inhabitants of any particular town for your depiction of them in a work of fiction, then you might as well give up and go home. Is the Newry of Orchid Blue bleak? Perhaps it is, but it is also full of mystery and possessed of a haunting beauty - you have to depict a place the way you see it.” / Orchid Blue paints the legal system surrounding this case, and also the Curran case, in a quite cynical light. When I ask was this something McNamee was aware of growing up in the area he reveals his insight was broader than most. “I grew up in a legal family, so I have a sense of that world, and how deeply corrupted it was. It’s one of the things that the book is about. If the Judge is tainted, then what recourse does man have?’ / Since the novel is so closely based on actual events, I wonder if McNamee had to spend as much time researching as he did writing. “I’m inclined to research the subject lightly before writing a book - to come away with impressions and textures. Then, when I’ve finished, I do in-depth research. I find, strangely, that when you get the story-telling right, the art and craft, the truth tends to follow it.”’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

[ top ]

Quotations

Resurrection Man (1994): ‘The city [...] has withdrawn into its place-names. Palestine Street. Balaklava Street. The names of captured ports, lost battles, forgotten outposts held against inner darkness.’ (p.3.) ‘There was someone out there operating in a new context. They were being lifted into unknown areas, deep pathologies. Was the cortex severed? they both felt a silence beginning to spread from this one. They would have to rethink procedures. The root of the tongue had been severed. new languages would have to be invented.’ (p.16). [Lenny: ‘India Street, Palestine Street. When he spoke them they felt weighty and ponderous on the tongue, impervious syllables that yielded neither direction nor meaning.’ (p.163.) [On the City Directory Coppinger finds in Lenny’s house:] ‘lamentation of the city was encrypted in its narration of street-names and dead inhabitants and lost occupations.’ (p.220.) [The foregoing chiefly quoted in Margaret Scanlan, ‘Eoin McNamee’s Resurrection Man’, in Plotting Terror [... &c.], 2001, as supra.]

Resurrection Man (1994): ‘[N]ewspapers and television were developing a familiar and comforting vocabulary to deal with violence. Sentences which could be read easily off the page. It involved repetition of key phrases. Atrocity reports began to achieve the pure level of a chant. It was no longer about conveying information. It as about focusing the mind inwards, attending to the durable rhythms of violence’ (q.p.) ‘The reporting of violent incidents was beginning to diverge from events. News editors had started to rework their priorities, and government and intelligence agencies were at work. Paramilitaries escorted journalists to secret locations where they posed with general purpose machine-guns and RP57 rocket launchers. Car bombings were carried out to synchronise with news deadlines.’ (p.58).

Resurrection Man (1994): ‘He said little about the killings themselves but he managed to convey the impression of something deft and surgical achieved at the outer limits of necessity, cast beyond the range of the spoken word where the victim was cherished and his killers attentive to some terrible need that he carried with him. Victor used the victim’s full names. He told her how he found himself in svmpathy with their faults and hinted that during their last journev he nursed them towards a growing awareness of their wasted years and arranged their bodies finally with an eye to the decorous and eternal. / Kill me.’ (p.174.)

The Blue Tango (2001): ‘I hear the mother’s bad with the nerves’, Tweed said. ‘Fuck me, what a house. The Desmond character playing on God’s team and the daughter flat on her back with the rakes of the country. There’s not much breeding there.’’ ‘She was lying on her left side and her right arm was raised, the wrist flexed as though in an overwrought gesture of farwell, although it was to be some time before a more sinister meaning was established from the position of her arm. Her clothing, from her neck to her thighs, was stained with blood.’

[ top ]

The Blue Tango (2001): ‘He [Rutherford] placed the back of his hand against her cold cheek and Rutherford knew then that Patricia Curran was beyond any absolution that Desmond’s prayers might bring.’ ‘Rutherford stepped back as they bent over forward like men determined to press a depraved suit upon the corpse’; ‘Desmond turned to Rutherford. In the torchlight his face looked pinched and guileful. “Thank goodness there was no sexual interference“, he said. Brandname phrases include: ‘tormented mannequin’; ‘macabre itinerary’; ‘exposure to terrible events had burdened her with an unexpected and bitter grandeur’ [Mrs Davidson]; ‘presiding over that empty domain [morgue] with a glassy, imperious stare’; ‘a kind of wondering revulsion’; ‘dark consecration’ [of the murder scene]; ‘dismal jurisdiction’ [of the Reverend Douglas]. (From longer extract in The Irish Times, 21 July, Weekend, p.11; the onward narrative is likewise folded with other interviews.)

‘A Border Life’, “Finishing Lines” [guest column], The Irish Times Magazine (15 Sept. 2001), narrates encounter and friendship with a ‘bogey’ [i.e., bogus] man living by his wits on the border; ‘Bogey Robert Nairac turned into radiant mince. Bogey Dominic McGlinchey lying stone dead outside a phone box in Drogheda with the receiver swinging on the end of its cord in a cold wind that seemed to blow from some place beyond redemption’; ‘The car was stopped at five different check-points. Even then, the presence of soldiers was taking on a [sic] overblown stagey [sic] feel, full of twitchy military mannerisms and affectations with men in full camouflage emerging from ditches, over-elaborate spookery, helicopters swooping in to land with unnecessary virtuosity: the Border giving the military men a chance to exercise there own version of the bathetic’; ‘He was suffering from what seemed to a be kind of eczema or dermatitis. The skin on his face was in bad shape and he looked out from behind it as though he wore some kind of scab mask, almost seeming a defensive thing, an [sic] laminate of affliction to protect him from some more unspeakable hurt.’; ‘Then a few years he was dead, shot in a grotesque incident reeking of sex and homicidal sorry but which, if you can withdraw a little form the smalltown carnage involved, then you can detect a theme of lethal sentimentality, coming through like a snatch of song’; ‘the dry-eyed and unbending find themselves without the necessary accommodations; the charlatans and Border-chancers endure.’ [p.82; End]. The piece also figures a distinction between the tabloid form of ‘romancing the dead’ by ‘accretion of new crimes’ and the status of the victim as father and husband.

Confronting violence: ‘My father was involved in the ’70s torture cases. He had all the literature and all the statements of these guys. I remember lying at night reading through these things. There was always a sense that f they were completely unmediated. But at the same time there was this kind of documentary thing, a kind of sense of witness about them that I think stink in somewhere. There’s no one reason, you can’t sort of imply that because you were brought up in the North in the ’70s that somehow you are psychologically damaged or vou have some sort of compulsion to deal with violence. A lot of writers tend to go the other way. Michael Longley said that he wanted to uphold the flag of Art in the face of Violence. There’s that kind of response to it as well. I did think that with Resurrection Man there was a very strong artistic impulse to confront it head-on and to deal with it and to redefine it ifyou like in terms of’ literature which I hope I succeeded with to some extent in that book.’ (See Rudie Goldsmith, in ‘Violence Real and Imagined’ , interview, in Fortnight, April 2003, p.18.)

Clarity and ‘faction’: ‘I think that writing about events can bring a certain clarity to them. The job of the artist is always to deepen the mystery, but sometimes by delving into the mystery we can find a truth. [...] I’m trying to create an atmosphere of the event and examine it but I can never reveal the whole thing. I never set out to say “this is what happened”.’ (Goldsmith, op. cit., April 2003, p.18 [idem.]; quoted in Clara McFall, UG Diss., UCC 2011.)

Difference between ...: On asked if he feels there is much difference between the violence of Jack Valentine and Victor Kelly: ‘Yeah, I do.There’s a kind of cartoonish element to the Jack Valentine violence. In Resurrection Man - in a way a part of the project there is to deal with real events and put it in a fictional setting. Cartoonish is maybe putting a bit too strong, it’s of the genre. They’re not meant to be taken terribly seriously. In one way I applied the pseudonym to put very clear blue water between the two types of writing.’ (Idem.)

[ top ]

Notes

Resurrection Man (1994): deals with the activities of a Shankill Butchers-type Loyalist death-squad in 1970s Belfast, and especially the killer Victor Kelly, clearly modelled on Lenny Murphy, who is pursued by the detectives Ryan and Coppinger. The character Billy McClure, a pederast, is modelled on William McGrath who was at the centre of the Kincora House scandal in which boys of 15 to 18 were abused over ten years, apparently with the connivance of MI5 and the police on the premise that McGrath was an agent gathering information on Protestant extremists. In 1982 Joshua Cardwell, a Belfast city councillor, committed suicide after the discovery of a desk diary at Kincora recording his visits there. In real life, only a tenuous link existed between the Butchers and the Kincora affair inasmuch as missing files in the Kincora case were connected with an officer involved in an enquiry into the murder of another prisoner by arsenic, purportedly perpetrated by Lenny Murphy who knew him to be a witness to another murder. (See Margaret Scanlan, ‘Eoin McNamee’s Resurrection Man’, in Plotting Terror [... &c.], 2001, p.39-40.)

Resurrection Man (1994) - A first novel which tells the story of the notorious Shankhill Butchers and sheds light on the political map of Belfast, where terrible deeds are committed in the name of history and religion. From the author of the Last of the Deeds and Love in History (both novellas).

Kirkus Reviews: With bite and brilliance, rising Irish star McNamee burrows deep, to the brutal core of sectarian violence in Belfast, where a young psychokiller is sanctioned for his efforts to raise urban terror to new heights: a chilling, first-rate debut. Victor’s dysfunctional family (silent father, bitterly brittle mother) can give no solace when he suffers beatings and false accusations of being the son of a Catholic, but he comes of age as fighting flares in Belfast, giving him ample opportunity to extract his revenge. With his handpicked unit, he quickly gains notoriety by snatching Catholics from the streets and carving them up with the meticulous care and eye of an artiste, before leaving the corpses in provocative poses. His work catches the eye of Catholic journalist Ryan, but no one wants to talk about this particular killer or his work, officially or unofficially. Then Victor is fingered by an informant and jailed, but he has well-placed allies who allow him to kill his betrayer in the man’s prison cell and soon regain the streets, where he again takes up his gruesome business in an amphetamine-induced frenzy - he and his gang now honored in graffiti with the name "Resurrection Men." Ryan, meanwhile, after a chance encounter with Victor’s girl, Heather, is pulled increasingly into her demimonde by the sinister McClure, Victor’s drug supplier, chief adviser, and handler. McClure steers Ryan to one of Victor’s victims, still undiscovered, then - because the haunted, unstable avenger has become more a liability than an asset - sets Victor up for assassination by taking him to visit his stroke-stricken father. The novel’s nice guy pales next to his driven, dark-shadowed counterpart, making the bloodletting as rendered the more intense - and the vision of evil unleashing and offing its own demons at will the more profoundly disturbing. An eerie, memorable debut. (Available at COPAC online; accessed 22.05.2011.)

Resurrection Man (1994) was filmed in 1998 with Stuart Townsend as Victor Kelly, Brenda Fricker as his mother, and Sean McGinley as the shadowy figure Sammy McClure [err. McLove]; dir. Marc Evans; Ryan, on Kelly’s trail, is ‘the journalist fed by the obsessive need to discover the truth about the killings ... putting his one life at risk’ (1.38 mins.; Revolution Films).

[ top ]

12.23: Paris, 31st August 1997 (2007): As the century grinds to a close Diana Spencer and her Egyptian lover are visiting Paris; an international fixer puts a team in place to watch the Princess and former Special Branch man John Harper is part of the team. Henri Paul, the Ritz Hotel’s Deputy Security Director and paparazzo supreme James Andanson are their surveillance targets but they’re not the only ones watching Spencer and soon much more sinister forces are on the move ... (See COPAC online; accessed 22.05.2011.)

The Navigator (2006): This is a time travel adventure in which a boy joins a rebel uprising against a sinister enemy - "The Harsh" - in order to repair the fabric of time. Owen’s ordinary life is turned upside-down the day he gets involved with the Resisters and their centuries-long feud with an ancient, evil race. The Harsh, with their icy blasts and relentless onslaught, have a single aim - to turn back time and eliminate all life. Unless they are stopped, everything Owen knows will vanish as if it has never been! But all is not as it seems in the rebel ranks. While Owen is accepted by new friends Cati and Wesley, and the eccentric Dr Diamond, others are suspicious of his motives. Could there be a Harsh spy in their midst? Where and what is the mysterious Mortmain, vital to their cause? And what was Owen’s father’s role in all this many years before? As he journeys to the frozen North on a mission of destruction, Owen comes to understand his own history and to face his destiny. (See COPAC online; accessed 22.05.2011.)

City of Time (2008): The world is in peril. There’s not enough time. The Navigator is needed once again! A year has passed since Owen said goodbye to Cati and relinquished his role as the Navigator, leaving the Resisters asleep on their island in time. But despite the victory over the marauding Harsh, Owen’s everyday life is still tainted by the enervating stupor affecting his mother. But gradually Owen becomes aware that strange occurences are happening around the world- meteorological events which don’t seem quite natural. And when he spies the vile Johnston snooping around the old Warehouse he suspects that villainy is afoot. When the Watcher summons, he knows he is needed, and reuinited Cati and Dr Diamond, they set off for the City of Time in search of a means to save the world. (See COPAC online; accessed 22.05.2011.)

Orchid Blue (2010): January 1961, and the beaten, stabbed and strangled body of a nineteen year old Pearl Gambol is discovered, after a dance the previous night at the Newry Orange Hall. Returning from London to investigate the case, Detective Eddie McCrink soon suspects that their may be people wielding influence over affairs, and that the accused, the enigmatic Robert McGladdery, may struggle to get a fair hearing. Presiding over the case is Lord Justice Curran, a man who nine years previously had found his own family in the news, following the murder of his nineteen year old daughter, Patricia. In a spectacular return to the territory of his acclaimed, Booker longlisted "The Blue Tango", Eoin McNamee’s new novel explores and dissects this notorious murder case which led to the final hanging on Northern Irish soil. (See COPAC online; accessed 22.05.2011.)

[ top ]

The Ring of Five (2010): The Ring of Five, ruthless leaders of the Lower World, are growing stronger. Wilsons spy academy is the only force left protecting the Upper World and its power is fading. They must find a spy to infiltrate the Ring, one who has the mark of the fifth, one who has treachery written on his heart. Danny is on the way to his new boarding school when he is kidnapped. He has been handpicked to join Wilsons, dedicated to the defeat of the ruthless Cherbs led by the Ring of Five. Danny makes friends and settles into his rigorous spy training. But with his different coloured eyes and his pointed features, he looks like a Cherb, attracting enemies and several attempts on his life. But no danger compares to the mission that Master Devoy sends him on: Danny must reach the Lower World to infiltrate the Ring. He is determined not only to be the best spy but to keep his friends. But he is soon to discover he can trust no one, not even himself ... (See COPAC online; accessed 22.05.2011.)

Glenn Patterson: The Belfast novelist Glenn Patterson makes brief reference to McNamee in ‘Reclaiming the Writing from the Walls’, Independent, II (9 Sept. 1994), [q.p.].

Typo: Aaron Kelly, ‘Belfast and Eoin McNamee’s Resurrection Man’, in Nicholas Allen & Aaron Kelly, ed., & intro., The Cities of Belfast (Four Courts Press 2003), is erroneously listed as ‘MacNamee’ on the Four Courts website publicity page [online]. Easy error to make!

[ top ]