Life

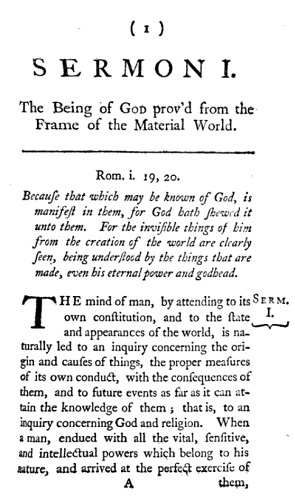

| 1680-1740 [‘the father of non-subscription’]; b. 19 Oct., Brigh, nr. Stewartstown, Co. Tyrone; his namesake father [freq. John Abernathy], moved to ireland as a Presbyterian minister, settled at Brigh and shortly moved to Moneymore, 1684; later lived in Ballymena and Coleraine; in 1688 he who went to London with John Adair to assert Presbyterian loyalty to William III; John was sent instead to relatives in Ballymena and conveyed by them to Scotland, where he was educated; some of his siblings died in the Siege of Londonderry where his mother had taken shelter; returned to family in Coleraine, 1692; entered Glasgow Univ., 1693, and grad. MA, 1696; studied Theology at Edinburgh Univ., returning to Ireland, 1701/02; ordained, Antrim 1703; m. Susannah Jordan (d.1712), with whom one son and three dgs.; |

| founded Belfast Society, with James Duchal, James Kirkpatrick (also a Glasgow graduate) and others, 1705 - in reaction against the Synod’s adoption of the Westminster Confession in that year; instructed to accept a call to Dublin by the Synod of Ulster but opted to stay in Antrim to the annoyance of the Synod, 1717; preached in Belfast the sermon Religious Obedience Founded on Personal Persuasion (1719 pub. 1720) disputing the ‘just limits of church power’ in the application of a Subscription to the Westminster Confession as creating ‘arbitrary enclosures within the Church of Christ’ by means of ‘the rigid test of an exact agreement in doubtful and disputable points’ - thus opening the First Subscription Controversy (1719-26); sequestered with other non-subscribers in the Antrim Presbytery by a Synod majority and the Elders, 1726; led the Unitarians - or non-subscribers with increasingly out-spoken Arian views - in the Belfast Society meeting-house, 1726; foresaken by his congregation and returned to Dublin; issuedNature and Consequences of the Sacramental Test Considered (Dublin 1731). |

| moved to Wood St. Meeting House, 1730; remarried; wrote against the Test Act inThe Nature and Consequences of the Sacramental Test Considered (1731) - in which he wrote that the Anglican Test Act ‘carries the appearance of public censure, at least distrust’ and further asserted his belief that ‘men of integrity and ability’ could come from all denominations, offering a natural-law defence of dissenters' rights to civil and military office and drawing a response from Jonathan Swift; with William Bruce - cousin of Francis Hucheson - he issued five pamphlets in response under the titleReasons for the Repeal of the Sacramental Test(1733), professing himself ‘against all laws that, upon account of mere differences of religious opinions and forms of worship excluded men of integrity and ability from serving their country’ (EB, 1911); consulted by William Bruce to show the first draft of System of Moral Theology to Abernethy for his opinion in 1737; |

| known as a member of Robert Molesworth’s “New Light” circle of liberal theologians in Dublin - the phrase coined for the non-subscribers by opposing clergyman John Malcolme of Dunmurry; his effort to change Parliament’s mind on dissenters’ civic status defeated in 1733; later cited by William Drennan as a formative influence on the thinking of the United Irishmen; he preached on the accession of George I in 1714 and on the centenary of the 1642 Rebellion; besides sermons - which were highly regarded by Dr. Johnston - he wroteDiscourses Concerning the Being and Natural Perfection of God [1740];Scarce and Valuable Tracts &c (1751); d. Dec. 1780. DIB ODNB CAB RR DUB OCIL FDA |

[top ]

Works

|

Bibliographical details

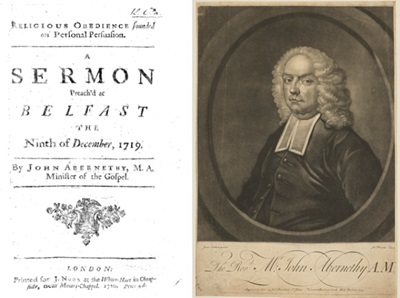

A Sermon Preach’d at Belfast, the Ninth of December 1719, by John Abernethy, Minister of the Gospel (London: J. Noon 1720).

Click on image to enlarge in separate window.

[top ]

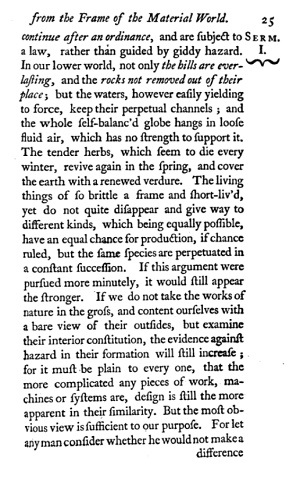

Discourses Concerning the Being and Natural Perfections of Godin Which That First Principle of Religion, the Existence of the Deity, Is Proved / from the Frame of the Material World, from the Animal and Rational Life, and from Human Intelligence and Morality / and / The Divine Attributes of Spirituality, Unity, Eternity, Immensity, Omnipotence, Omniscience, and Infinite Wisdom, are explain’d . [Vol. 1] By John Abernethy,M.A. (Dublin: Printed: London, Reprinted for H. Whitridge, at the Royal Exchange, MDCC.XLVI. - 1740; available at Google Books - online [accessed 22.09.2020]

|

|

|

| —Available at Google Books -online; accessed 22.09.2020. | ||

| Note: Abernethy uses the word ‘commodiously’ (p.30) in connection with the supply of heat on earth—‘But no one can avoid observing the changes of the seasons, occasion’d by the annual (apparent) course of the sun. If he kept one perpetual track, the greatest part of the earth must be uninhabited, either by reason of excessive heat or cold; the gloomy regions never visited by him, must be shut up in continual darkness and impenetrable frost, while the climates on which his beams should still [30] directly fall, must be quite burnt up, yielding on sustenance for man or beast. But instead of these extremes, how commodiously is this great benefit dispensed, by the fixed periodical revolutioin of the great orb in a yearly couorse, so direct, as to prevent, as far as can be the excesses both of heat and cold, and produce the grateful and useful variety of summer and winter, seed-time and harvest.’ (pp.29-30.) |

|

[top ]

Criticism

|

See also—

| Rev. Martin C. Cowan, ‘Francis Hutcheson and the 300th anniversary of the beginning of the First Subscription Controversy’ Union Theological College Blog (12.12.2019) |

|

| —Available online; accessed 21.09.2020. |

| David Steers, The First Subscription Controversy, in “The History of the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland” [No. 1] The Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Wordpress |

|

| —Available online; accessed 21.09.2020. |

[top ]

| Fergus Whelan, ‘Oliver Cromwell: father of Irish republicanism?’, in History Ireland (Nov/Dec 2010) |

|

| —Available online; accessed 21.09.2020. |

[top ]

Quotations

“The Existence of God Proved by Human Morality” (fromDiscourse Concerning the Being and Natural perfections of God, 1743): ‘Nothing can be more groundless and unsupported with any pretence of reason than to allege that the notions of morality so common and prevailing in the world were originally invented by politicians, and by their artifice imposed upon credulous mankind as the dictates of nature. For besides that strict virtue is often too little agreeable to the maxims and measures of their policy to give it any appearance of proceeding from such an original, every man who will look carefully into his own heart may find there a standard of right and wrong prior to any instructions, declarations, and laws of men, whereby he pronounces judgment upon them. Nor was it ever known that any human invention, nor anything which was not the voice of reason and nature itself, appeared so uniform and unvaried, always consistent with itself, and always in the same light to the minds of men, as the principal moral species do. The forms of civil government differ according to the circumstances and inclinations of the people who create them, the external forms of religion too are variable, and so is everything of positive appointment and institution; but justice and mercy, gratitude and truth, never alter; the learned and the unlearned, the most uninstructed and the most polite nations agree in their notions concerning them, and whenever they are intelligibly propose approve them.’ (Extract in Charles Read, ed,.The Cabinet of Irish Literature, 3 vols., 1876-78, Vol. 1, p.162.)

“Christianity Opposed to Persecution” (fromDiscourse Concerning the Being and Natural Perfections of God, 1743): ‘All this is not to be understood as if Christianity were intended to destroy the unalterable right of mankind to defend their lives and their liberties, among which that of conscience is the most sacred, against unjust violence, as if we were obliged by the rules of our religions to offer our throats to ruffians, and submit universally to the most lawless tyranny. But the religion of the Holy Jesus forbids revenge. Even when necessary, self-defence is allowed, nay, is most just and honourable. Christians should be always ready to be reconciled, never carrying their resentment farther than self-preservation requires. When that end is obtained, and force is no more needed to repel causeless wrongs, then the offices of love take place; the utmost cruelties ought not to be retaliated. In the case of the apostles and other primitive Christians the right of self-defence was entirely out of the question. Their situation was such that it was not in their power to use it. And so God was pleased to order, in his infinite wisdom, that in them might be exemplified illustriously the virtues of meekness, patience and charity, which are the glory of his gospel, for a pattern to all who should afterwards believe, and for a testimony to the world of the truth, the purity, and the innocence of the Christian faith. But at all times Christianity appears, as originally delivered by its blessed Author, to be an inoffensive institution, breathing nothing but peace, and tending to inspire its professors with the strongest sentiments of kindness and good-will to all men - kindness not to be extinguished even by hatred, injuries, and affronts, so far from giving any allowance to rage and cruelty in the defence and provocation of it; of which we have a remarkable instance in the severe reproof our Saviour gave to two of his disciples, who moved to have fire come down from heaven to a destroy some of the Samaritans because they refused to receive him into their village. He turned and rebuked them and said, “Ye know not what manner of spirit ye are of, for the Son of man is not come to destroy men’s lives, but to save them.”’ (Extract in Charles Read, ed,.The Cabinet of Irish Literature, 3 vols., 1876-78, Vol. 1, p.164; see also pages shown - as supra.)

[top ]

Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies, Vol.I [of 2] (London & Dublin 1819; 1822), pp.1-6. |

|

AN eminent presbyterian divine, was born on the 19th of October, 1680, at Coleraine, in the county of Londonderry. His father was a dissenting minister in that town, and his mother of the family of the Walkinshaws, of Renfrewshire in Scotland. After remaining under the care of his parents for nine years, he was separated from them by a chain of circumstances, which, in the end, proved highly favorable [sic]. His father had been employed by the presbyterian clergy to transact some public affairs in London, at a time when his mother, to avoid the tumult of the insurrections in Ireland, withdrew to Derry. Their son was at that period with a relation, who in the general confusion determined to remove to Scotland, and having no opportunity of conveying the child to his mother, carried him off along with him. Thus he providentially escaped the dangers attending the siege of Derry, in which Mrs. Abernethy lost all her other children. Having spent some {2} years at a grammar school, at the early age of thirteen he was removed to the college at Glasgow, where he remained till he had taken the degree of master of arts. [...] In 1716, he attempted to remove the prejudices of the native Irish, in the neighbourhood of Antrim, who were of the popish persuasion, and induce them to embrace the protestant religion. His labours in this design. were attended with but moderate success, for notwithstanding several, who were induced to abandon popery, continued firm in their attachment to protestant principles, yet others, to his great discouragement and mortification, reverted to their former persuasion. In the following year he received two invitations, one from Dublin, and sitter from Belfast; and the synod (whose authority at that time was very great) advised his removal to Dublin; but so strong was his attachment to his congregation at Antrim, that he {3} resolved to continue there at the peril of incurring their displeasure. The interference of this assembly was diametrically opposite to those sentiments of religious freedom which Mr. Abernethy had been led to entertain, both by the exercise of his own vigorous faculties, and by an attention to the Bangorian controversy which prevailed in England about this period. Encouraged by the freedom of discussion which it had occasioned, a considerable number of ministers and others in the north of Ireland, formed themselves into a society for improvement in useful knowledge; their professed aim was to bring things to the test of reason and scripture, instead of paying a servile regard to any human authority. This laudable design is supposed to have been suggested by Mr. Abernethy, and as the gentlemen who concurred in the scheme met at Belfast, it was called The Belfast Society. In the progress of this body, and in consequence of the debates and dissensions which were occasioned by it, several persons withdrew from the society, and those who adhered to it were distinguished by the appellation of non-subscribers. Their avowed principles were these, “First, that our Lord Jesus Christ hath in the new testament determined and fixed the terms of communion in his church; that all christians who comply with these have a right to communion, and that no man, or set of men, have power to add any other terms to those settled in the Gospel. Secondly, that it is not necessary as an evidence of soundness in the faith, that candidates for the ministry should subscribe to the‘ Westminster confession, or any uninspired form of articles or confession of faith, as the terms upon which they shall be admitted, and that no church has a right to impose such a subscription upon them. Thirdly, that to call upon men to make declarations concerning their faith, upon the threat of cutting them off from communion if they should refuse it, and this merely upon suspicions and jealousies, while the persons required to purge themselves by such declarations cannot be fairly convicted upon evidence of any error or {4} heresy, is to exercise an exorbitant and arbitrary power, and is really an inquisition.” (pp.1-4) |

| See full-text copy in RICORSO > Library > Criticism > History > Legacy - via index, or as attached. |

[top ]

Charles A. Read,The Cabinet of Irish Literature [1876-78]; erroneously cites place of birth as Coleraine, prob. confusing the town with former Coleraine County (later Co. Londonderry); also mentions the death of [all] his siblings in the Williamite War, here called ‘dissensions’. Reprints extracts fromDiscourses Concerning the Being and Natural Perfection of God (1743) andCollected Tracts [n.d.].

British Library holds: A Sermon preached at Antrim, Nov. 13. 1723, at a fast observed in the Presbyterian Congregations in Ulster [...] on the account of divisions. Belfast: Robert Gardner 1724), 4o., pp. 24; A Sermon recommending the Study of Scripture-Prophecie, etc. (Belfast: James Blow 1716), 4o, 25pp.; Discourses concerning the being and natural perfections of God, &c. (Dublin: for the author 1740), 400pp., 8o.; Discourses concerning the being and natural perfections of God [Fourth edn.], 2 vols. (Aberdeen: J. Boyle 1778), 12o.; Discourses concerning the Being and Natural Perfections of God, etc., 2 vols (London: H. Whitridge 1743), 8o; another edn. [Third Edition], 2 vols. [Dublin] (London rep. for H. Whitridge 1746), 8o.; Another Edn. (London H. Whitridge, D. Browne, etc.1757), 8o.; Discourses concerning the Being and Natural Perfections of God, etc. (Dublin: J. Smith 1742), 8o., 440pp.; Persecution contrary to Christianity. A sermon preached in [...] Dublin on the 23d. of October 1735, being the anniversary of the Irish Rebellion. (Dublin: J. Smith & W. Bruce 1735, 8o., pp. 44; Religious Obedience founded on Personal Persuasion. A sermon, etc.. London: J. Noon: 1720), 8o., 28pp.; Scarce and Valuable Tracts and Sermons, occasionally published by the late [...] John Abernethy [...] now first collected together (London: R. Griffiths 1751). 8o. [7, 288pp.]; Seasonable advice to the Protestant Dissenters in the North of Ireland; being a defence of the late General Synod’s charitable Declarations [i.e., the proceedings of the Synod at Belfast, 27 June 1721]. With a recommendatory preface. By the Reverend Nath[aniel] Weld, J. Boyse and R. Choppin. [by J. Abernethy] (Dublin: George Ewing 1722), 8o, xxii, 57pp.; Sermons on Various Subjects [...] With a large preface [by James Duchal] containing the life of the author.; [another edn. of Vols. 1 and 2.]; another edn. [The Third Edition] 4 vols. (London: D. Browne; C. Davis; A. Millar 1748-51), 8o.; Another edn. (London: D. Browne; T. Osborne; A. Millar 1762). 8o.; The People’s Choice, the Lord’s Anointed. A thanksgiving sermon for [...] King George, his happy accession to the throne, his arrival and coronation. Preach’d at Antrim, etc. (Belfast: R. Gardner [1714]), 4o. 20pp.; The True Terms of Christian and Ministerial Communion founded on Scripture alone. A sermon [...] With a preface: containing a short account of the author, by Mr. Abernethy.. pp. xii. 24. J. Smith: Dublin, 1739. 8o.; The Nature and Consequences of the Sacramental Test considered: with Reasons humbly offered for the repeal of it. [by John Abernethy] (Dublin 1731), 63pp.; another edn. [rep.] (London: J. Roberts 1732), . 8o.. 79pp.; A Sermon [on Matt. xxv. 21] on occasion of the [...] death of the Revd Mr. J. Abernethy, preach’d [...] Dec. 7th, 1740, etc. (Dublin 1741), 8o. Also SERMONS, Eleven Sermons on the Being and Perfections of God [A sermon]; Of Acknowledging God in all our ways [A sermon]; Of Repentance [2 sermons]; Of Self-Denial [A sermon]; The Causes and Danger of Self-Deceit. [A sermon]. Note, BL Cat. also contains theological works of one John Abernethy, Bishop of Caithness [e.g., A Christian and Heavenly Treatise, containing physicke for the soule [...] Newly corrected and inlarged by the author. [Third edition] (London: J. Budge 1622; 1630); trans. as Een Christelick ende Goddelick Tractact, inhoudende de medicine der ziele, etc. (s’ Graven-hage: A. Meuris: 1623), 4o.]; also numerous works by the distinguished medical practitioner and author John Abernethy (fl. 1830) and a biography of same.

Dictionary of National Biography refers to ‘his zeal on behalf of his ignorant and superstitious countrymen [i.e. Catholics]’; Abernethy stood uncompromisingly for religious freedom and disowned sacerdotal assumptions of the ecclesiastical courts; head of non-subscribers to the Presbyterian Synod, which was cut off in 1726. [Note that theDictionary of Irish Biography entry is a distillation of this.]

James S. Donnelly, Jr., et al., eds.,Encyclopedia of Irish History and Culture, 2 vols. (Macmillan Reference USA [Thomson Gale] 2004), commences with an article on Abernethy [Vol. I].

Seamus Deane, gen. ed.,The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, 3 vols. (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3, p.19: [ftn. to William Drennan, ‘The Intended Defence’].

[top ]

Notes

John Larkin,The Trial of William Drennan (1991) includes remarks to the effect that William Drennan wrote in his “Defence”: ‘I glory to be a Protestant Dissenter and proudly recited the names of Abernethy, Bruce, [John] Duchal and [Francis] Hutcheson. Not only were these men all close friends of his father but they were exponents of a particular kind of Presbyterianism - a new liberal attitude which an opponent ironically termed the “New Light”. In the 1720s, this movement was at the centre of a division in the Irish Presbyterian Church on the question of subscription to the Westminster Confession of Faith, and Abernethy and Bruce, together with Samuel Haliday, the elder Drennan’s predecessor as minister of the First Presbyterian Church Belfast, and others were leaders of the liberal ‘non-subscribers.’ (See review by John W. Nelson,The Linen Hall Review, April 1991.) Note that these same men were cited in a sermon preached by James Mackay in the Old Belfast Meeting House on the death of Drennan’s father.

Namesake: George MacIlwain, FRCS, Memoirs of John Abernethy, with a View of His Lectures, His Writings, and Character [...] [3rd Edn.] (London: Hatchard 1856), concerns another person of the name. [See Gutenberg -online; accessed 21.09.2020.]

Query: preached at Ussher’s Quay, Dublin. c.1690?

[top ]