|

John Banville

Life

| 1945- [William John Banville; pseud. “Benjamin Black”, for Quirke mystery series; occas. as “B. W. Black”, and ‘John Banville writing as Benjamin Black’]; b. 8 Dec., Wexford, son of office worker in garage-supply business; ed. Christian Brothers, and St. Peter’s College, Summerhill, Wexford, where he was taught by Fr. Larkin; bought copy of Ulysses in Liverpool at 17; intended for architect by parents; working as Aer Lingus clerk, 1968; m. an American, 1968; joined Irish Press, 1980; literary editor of The Irish Times, 1988-98 [var. 1999]; wins Allied Irish Banks and Irish-America Found. Lit. Awards, 1967; Macaulay Fellowship of Irish Arts Council, 1973; short stories, Long Lankin (1970), all involving an outsider and his effect on other characters and based on the Scottish ballad of that name dealing with the death of a child; Nightspawn (1971), a psychological thriller and anti-novel set in Greece on the eve of a military coup and narrated by Irish writer Ben White, who becomes involved; |

| |

| issued Birchwood (1973), set in an Irish ‘big house’ combining features of different historical periods, and centred on the narrator Gabriel Godkin’s discovery that his ‘cousin’ Michael is actually his brother from an incestuous relationship between his father and his aunt - with jealousies, violence and deceits arising from these circumstances; compared in reviews with Jennifer Johnston to the disappointment of the author; issued Doctor Copernicus (1976), based on the life of the astronomer Copernicus [Koppernigk], and winner of James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction; issued Kepler (1981), in the same vein and likewise grounded in Koestler’s study of scientific paradigms in The Sleepwalkers (1959); |

| |

| completed ‘scientific’ trilogy with The Newton Letter (1982), set in Ferns, where the scientist’s biographer takes accommodation with the Lawlesses and becomes involved with the daughter of the house; reputed to be Banville’s favorite and filmed for Channel 4; issued Mefisto (1986), a Faustian tale narrated by Gabriel Swan in two parts, before and after his own part-immolation in a burning ‘big house’ and ultimately concerned with matematical models of reality - a theme and treatment oddly in the manner of Flann O’Briens “De De Selby” character in The Third Policeman; author’s expectations of popular success disappointed by unfortunate timing of British reviews of the novel; |

| |

| issued The Book of Evidence (1989), dealing with Freddie Montgomery’s killing of Josie Bell in circumstances not unlike those in the 1982 Macarthur murder case (‘all just drift, like everything else’), with an obsession with a Dutch painting lost to the character’s Anglo-Irish family as the immediate cause of the criminal events; shortlisted for Booker Prize and winner of 1989 Guinness Peat Aviation [GPA] Award - but only after a fracas involving the adjudicator Graham Greene and the unlisted entrant [Vincent McDonnell]; brought Banville his first popular success; issued Ghosts (1993), a novel about film-crew arriving on an island, with Montgomery under alias; wrote The Broken Jug (Peacock, 1 June, 1994; dir. by Ben Barnes), a stage-farce in verse adapted from Heinrich von Kleist’s Der Zebrochene Krug [1807], and dealing obliquely with the Famine; |

| |

| wrote Seachange (Autumn 1994), his first TV drama, appeared in RTÉ “Two Lives” series, produced by Focus Th. along with Michael Harding’s play Kiss; issued Athena (1995), the third in a trilogy centred on Freddie Montgomery, now alias Morrow; issued The Untouchable (1997), a novel centred in career of Victor Maskell and based on story of the aesthete-spy Anthony Blunt (d.1983); it incls. the character Querell, widely held to be based on Graham Greene; rebuked journalists’ for ‘intrusive and inaccurate’ stories about his private life (Hot Press, 9 July 1997); winner Lannan Literary Award, 1997 ($75,000); mbr. of Irish Arts Council under Colm Ó Briain’s directorship in the 1980s; succeeded by Caroline Walshe in literary-editorship of Irish Times and becomes Chief Critic in succession to Brian Fallon, 1999; |

| |

| issued Eclipse (2000), in which Alexander Cleave, an actor, narrates his retreat into himself after a humiliation on the stage but has to come to terms with his family and especially his troubled dg. Cass - followed by Shroud (2002) and Ancient Light (2012) to for a trilogy; God’s Gift, based on von Kleist’s version of the tale of Amphitryon’s wife (Barabbas, Dec. 2000); contrib. essay to first issue of the new-series Dublin Review; resigned from Aosdána following non-election of his candidate Mary Morrissey, 2001; isued Shroud (2002), a sequel to Eclipse; issued Prague Pictures (2003); strenuously criticises Ian MacEwan’s novel Saturday, in The New York Review of Books (26 May 2005); |

| |

| issues The Sea (2005), in which Max Morden remembers an summer with the Graces, a family of twin children Chloe and Myles with their parents Carlo and Constance; winner of Man Booker Prize (‘it’s the biggest toy in the shop’); issued, as Benjamin Black [pseud.], prepared tv mini-series set in 1950s Ireland in the early 2000s, which however remained unproduced - but was later turned into Christine Falls (2006), first of the Benjamin Black novels featuring the Dublin pathologist and crime-novel anti-hero Quirke - and written at Santa Maddalena, south-east of Florence (Tuscany), hosted by Beatrice von Rezzori, widow of Gregor von Rezzori; |

| |

| issued The Silver Swan (2007), also as Bejamin Black, in which Garret Quirke, a pathologist, investigates the supposed suicide of a friend’s wife, bringing on a tale of blackmail, prostition, pornography and drugs; issued Conversations in a Mountains (2008), a play in which Jewish poet Paul Celan visits Martin Heidegger, hoping to hear his apology for complicity in the Holocaust; issued The Lemur (2008), as Benjamin Black, a murder tale set in New York introducing a new protagonist, John Glass; gave the keynote lecture at the Kate O’Brien Weekend in Limerick Courthouse, 2009; |

| |

| issued The Infinities (2010), a novel which imagines the Greek gods living through contemporary beings in the form of a mathematician Adam, now dying of a stroke, and his family gathering about him in a latter-day big-house setting - with a deeply counterfactual historical plot-line as regards events in Ireland and the world - an excerpt appearing in the New York Times on 5 March 2010; issued Elegy for April (2010), another Benjamin Black novel, and A Death in Summer (2011), in which Diamond Dick [Richard Jewell] owner of the Clarion newspaper, is found decapitated by a gunshot; winner of 2011 Kafka Prize; |

| |

| issued Vengeance (2012), as Benjamin Black; as Banville, issued Ancient Lights (2012), in which Alex Cleave falls in love with a friend’s mother in teenage; winner of Bórd Gáis Energy Irish Book Awards Novel of the Year; four Benjamin Black novels filmed in BBC with Gabriel Black as Quirk, 2014; issued The Blue Guitar (2015), narrated by Oliver Otway Orme, a self-aggrandising and self-deprecatory painter of some renown and a petty thief who has never before been caught; issued Mrs Osmond: A Novel (2017) - a continuation of Henry James’s the Portrait of a Lady and written while visiting professor at the University of Chicago; in 2020 the Brazilian Assoc. of Irish Studies published a special issue celebrating fifty years of the publication of Long Lankin (ABEI, 22:1 Sao Paolo 2020); in July 2022 Banville joined others including Noam Chomsky, Margaret Atwood, and J. K. Rowling in signing an international authors’ letter calling for an end to ‘cancel culture’, the anti-liberal campaign of ‘progressive’ cultural activists to silence alternative voices particularly in relation to historical issues of race and gender. DIW FDA AOS DIL OCIL |

| [ top ] |

|

|

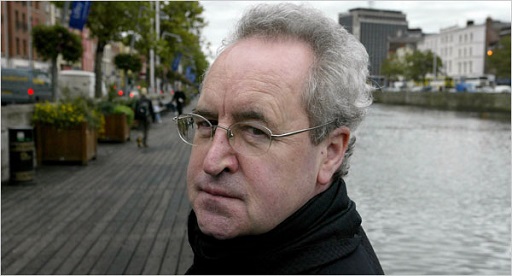

| Photo-ports by various photo-journalists; top left by Derek Speirs (NY Times); top right by Gerry Mooney (Irish Independent, 2020). |

[ See Translating Banville - infra ]

Works

| Fiction |

- Long Lankin (London: Martin Secker & Warburg 1970), 189pp. [“Wild Wood”; “Lovers”; “A Death; “The Visit”; “Sanctuary”; “Nightwind”; “Summer Voices”; “Island”; “De rerum natura”], and Do. [1st rev. edn.] (Dublin: Gallery Press 1984), 91pp. [without “Persona” and “The Possessed” but incl. “De Rerum Natura”].

- Nightspawn (London: Martin Secker & Warburg; NY: Norton 1971; Oldcastle: Gallery 1993).

- Birchwood (London: Martin Secker & Warburg 1973; London: Panther 1984; London Minerva 1992; NY: Norton 1994; London: Picador 1998; 1999, Picador 2011), 176pp.

- Doctor Copernicus (London: Martin Secker & Warburg/NY: Norton 1976), 242pp.; Do. [other edns.] (London: Panther 1980; London: Granada 1983; Paladin 1987; London: Minerva/Mandarin 1990; NY: Vintage 1993; London: Picador 1999). [Note: 1st edn. incl. map drawn by Cartographic Enterprises from an original drawing by Seamus McGonagle.]

- Kepler (London: Martin Secker & Warburg 1981; London: Panther/Boston: Godine 1983).

- The Newton Letter: An Interlude (London: Martin Secker & Warburg 1982; London: Panther 1984; Boston: Godine 1987).

- Mefisto (London: Martin Secker & Warburg 1986; Boston: Godine 1989; Minerva 1993).

- The Book of Evidence (London: Martin Secker & Warburg 1989; NY: Scribner 1990; Minerva 1990; Mandarin 1990; London: Picador 1998; NY: Vintage 2001) [220pp.]; Do., 25th Anniversary Edition, with intro. by Colm Tóibín, and supplementary material compiled and edited by Raymond Bell (Picador 2025).

- Ghosts (London: Martin Secker & Warburg/NY: Knopf 1993), 244pp.

- Athena (London: Martin Secker & Warburg 1995; London: Picador 1998, rep. 2011), 246pp.

- The Untouchable (London: Picador 1997; 1998).

- Eclipse (London: Picador 2000), 214pp. [ded. ‘in mem. Laurence Roche’].

- Shroud (London: Picador 2003), 408pp.[unnum. pages]; Do. [rep.] (Picador 2011), 416pp. [detective & mystery stories; savants; Turin; reminiscing ...]

- The Sea (London: Picador 2005), 264pp.

- The Infinities (NY: Alfred A. Knopf 2010), 273pp.

- Ancient Light (Viking Penguin 2012), 304pp. [loss, memory, older men, actors ...]

- The Blue Guitar: A Novel (NY: Alfred Knopf 2015), 272pp.

- Mrs Osmond: A Novel (NY: Alfred Knopf 2017; London: Penguin 2018), 384pp.

- Snow (London: Faber & Faber 2020) [detective & mystery stories]

- The Secret Guests (NY: Henry Holt & Co. 2020), 291pp.; Do. [rep.] (London: Penguin Books 2020), 388pp. Do. [rep.] (London: Picador 2021), 304pp.; Do. [rep] (Thorndike Press [Gale/Cengage] 2021), 275pp.

- The Singularities (NY: Alfred A. Knopf 2022; London: Swift Press 2023), 307pp.

- The Lock-up (Faber & Faber 2023), 352pp.

- The Drowned: A Stafford and Quirke Murder Mystery by John Banville (London: Faber & Faber 2024), 352pp.

|

| [ top ] |

| As Benjamin Black [the Quirke Dublin Mysteries] |

- Christine Falls: A Quirke Dublin Mystery (London: Hodder & Stoughton 2006), 310pp.; Do. [rep.] (London: Picador 2013), 405pp.

- The Silver Swan: A Novel (London: Picador 2007), 344pp.

- The Lemur (London: Picador 2009), 200pp.

- Elegy for April (London: Mantle 2010; rep. Picador 2011), 310pp. ; Do. [large type] (Oxford: Isis 2011), 332pp.

- A Death in Summer ([Mantle] 2011), 256pp. [Quirke Dublin Mysteries].

- Vengeance (London: Mantle 2012), 313pp.

- Holy Orders (London: Mantle 2013), 256pp.; Do. [rep.] (London: Picador 2014).

- The Black-Eyed Blonde: A Philip Marlowe Novel (London: Mantle 2014), 256pp.

- Even the Dead (London: Penguin; Henry Holt & Co. 2016), 304pp. [cover sub-title: ‘No crime is ever truly buried ...’.

- Prague Nights (London: Viking [Penguin Books] 2017), q.pp. [set in Prague, 1599]; iss. in USA as Wolf on a String (Henry Holt & Co. 2017), 320pp. [reviewed by Clare Clark, in The Guardian, 7 June 2017 - available online.]

|

| [ top ] |

| Poetry & Drama |

- God’s Gift [after Kleist] ([Oldcastle: Gallery Press] 2000), q.pp.

- Love in the Wars: A Version of “Penthesilea” by Heinrich von Kleist] (Oldcastle: Gallery Press 2005), 78pp.

- Conversations in a Mountains (Oldcastle: Gallery Press 2008), 64pp., ill. [by Donald Teskey].

|

| Miscellaneous |

- Prague Pictures: Portraits of a City (London: Bloomsbury 2003), 256pp.

- Preface to The Snows of Yesteryear: Portraits for an Autobiography, by Gregor von Rezzori, translated by H.F. Broch De Rothermann [NY Review of Books Classics] (NY 2009) [rep. in Irish Times, 25 April 2005, Weekend].

- Time Pieces: A Dublin Memoir (London: Faber 2016), 224pp., ill. [photos by Paul Joyce].

|

| Articles (selected) |

- ‘Act of Faith’, in Hibernia, September 2 (1977), p.8.

- ‘A Talk’, in Irish University Review [John Banville Special Issue] (Spring 1981), p.16.

- ‘Physics and Fiction: Order from Chaos’, in The New York Book Review (21 April 1985), p.41 [see contributions to New York Review of Books, 1990-2007 [as infra].

- ‘Birchwood: Extracts from the Screenplay’, John Banville & Thaddeus O’Sullivan with Andrew Patmann, in Irish Review, 1 (1986), pp.65-73.

- ‘Thou Shalt not Kill’, in Arguing at the Crossroads: Essays on a Changing Ireland, ed. Paul Brennan & Catherine de Saint Phalle (Dublin: New Island Books 1997), pp.133-142.

- ‘Bloomsday, Bloody Bloomsday’, in New York Books Review (16 June 2004) [“Essay”], p.31 [see extract].

- John Banville, ‘Fiction and the Dream’, in Irish Studies in Brazil, ed. Munira H. Mutran & Laura P. Z. Izarra [Pesquisa e Crítica, 1] (Associação Editorial Humanitas 2005), 21-28 [see extract].

|

|

[ top ] |

| Journalism (selected) |

- ‘Joyce and Neitszche’ [lecture & essay], in Augustine Martin, James Joyce, The Artist and the Labyrinth (London: Ryan Publishing 1990) [q.pp.]; also ‘Survivors of Joyce, ’ in Ibid., pp.73-81.

- ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem’, review of Derek Mahon, Selected Poems, and Paul Muldoon, Madoc: A Mystery, in NY Review of Books (30 May 1991), pp.37-39.

- The Broken Jug (Dublin: Gallery 1994); ‘Introduction’ to George Steiner, The Deeps of the Sea (London: Faber 1995) [q.pp.].

- ‘The Writing Life’, in Washington Post [Book World section] (9 Sept 1999), p.8.

- John Banville, ‘The Tragicomic Dubliner’, review of No Laughing Matter: The Life and Times of Flann O’Brien by Anthony Cronin, and At Swim-Two-Birds, in The New York Review of Books (18 Nov. 1999) [available online]

- ‘Fate of the Fourth Man’, review of Miranda Carter, Anthony Blunt: His Lives, in The Irish Times ( 24 Nov. 2001).

- ‘Lucia Joyce: [review of] To Dance in the Wake by Carol Loeb Shloss’, in ABEI Journal: The Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies, 6 (June 2004), pp.11-18.

- ‘Bloomsday, Bloody Bloomsday’, in New York Times Book Review (13 June 2004), p.31.

- ‘A Quantum Leap to Clontarf’, review of Neil Belton, ‘A Game with Sharpened Knives’, in The Irish Times, 11 June 2005, Weekend [infra].

- [...]

- ‘Translating Rilke: An Exchange - Richard Stern and John Friedmann, reply by John Banville’, in The NY Review (29 March 2007) [response to Banville’s review of Letters from the Heights (NYR, 21 Dec. 2006) - available online; accessed 29.12.2024

- ‘Making Marilyn’, review of MM - Personal, by Lois Banner & Mark Anderson, and Fragments, ed. Stanley Buchthal & Bernard Comment, in The Irish Times (9 July 2011), Weekend Review, p.11 [full-page].

- Review of Arguably, by Christopher Hitchens, in The Irish Times (1 Oct. 2011), Weekend, p.10.

- Introduction to The Eggman and the Fairies, by Hubert Butler, rep. in The Irish Times (1 Dec. 2012), Weekend, p.10 [see extract under Butler, supra].

- [...]

- ‘John Banville celebrates Richard Ford’s Bascombe books: the story of an American Everyman’, in The Guardian (8 Nov. 2014) [available online].

- ‘My Hero: Flann O’Brien by John Banville’, in The Guardian (1 April 2016) - available online.

- ‘Ending at the Beginning’, review of Kafka: The Early Years by Reiner Stach, trans. Shelley Frisch (Princeton UP), in New York Review of Books (17 Aug. 2017) - available online or as attached.]

|

| The Wikipedia entry on Banville incls. extensive listings of his reviews and prefaces & introductions - online. |

|

| Selected edn. |

- Raymond Bell, sel., Possessed of a Past: A John Banville Reader (London: Picador 2012), xvii, 501pp. [essays]

|

|

| |

| See also sundry journalism in Quotations, infra. |

| [ top ] |

| TV drama |

- Seachange, appeared in RTÉ “Two Lives” series (Autumn 1994).

|

| Radio |

- “Stardust: Three Monologues of the Dead” [Copernicus, Kepler, Newton], read by Gordon Read, BBC2, 11 May 2002.

- [...]

- ‘John Banville and 1950s Dublin’ [“Open Book prog.”; Literary Landscape ser.; walking interview], BBC4 (14 Aug. 2014) [28 mins.; a tour of foggy streets and shabby, smoke-filled bars and writers such as J. P. Donleavy; with Mariella Frostrup; available for 1 year - online].

|

| |

| Miscellaneous (Prefaces & Introductions) |

- John Blakemore, The Stilled Gaze (London: Zelda Cheatle Press 1994), 65pp., ill. [ [introductory essays by Banville and Judith Bumpus; ed. by Michael Mack; designed by Howard Brown].

- Magnum Ireland, ed. Brigitte Lardinois & Val Williams; essays by Anthony Cronin [et al.]; preface by Enrique Juncosa; introduction by John Banville (London: Thames & Hudson in assoc. with IMMA 2006, 256pp. [chiefly ills., some col.; Contents: ’50s; ’60s; ’70s; ’80s; ’90s; ’00s; Ireland and Photography: Partial Histories Brigitte Lardinois, Val Williams p248ff.]

- Intro., Dracula, by Bram Stoker; ill. by Abigail Rorer (London: Folio Society 2008), xv, 1lf., 355pp.; ill. [9 unnum lvs. of pls.; 1 color), 20cm.

- Foreword, First We Read, Then We Write: Emerson on the Creative Process. [Muse Books] (Iowa UP 2009), 118pp. [Contents: Introduction; Foreword by John Banville; Introduction; Reading; Keeping a Journal; Practical Hints; Nature; More Practical Hints; The Language of the Street; Words; Sentences; Emblem, Symbol, Metaphor; Audience; Art Is the Path; The Writer; Epilogue; Acknowledgments; Notes; Index.

- Intro., All Souls [novel] by Xavier Marías; trans. by Margaret Jull Costa, with an introduction by John Banville [Penguin Modern Classics] (London: Harvill 1992; rep. London: Penguin Books 2012), xv, 209pp. [being and English translation of Todas las almas [Spanish]; Intro. bears copyright date of 2012.]

- ed. The Invader Wore Slippers: European Essays, by Hubert Butler, (London: Notting Hill Editions 2012), 271pp.

- Intro., Rogue male, by Geoffrey Household; ill. by David Rooney (London: The Folio Society 2013), x, 147pp., il. [6 unnum lvs. of b&w pls., 23 cm [text of first edn., London: Chatto & Windus 1939].

- The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Chapters in the History of Ideas, by Isaiah Berlin; ed. Henry Hardy; foreword by John Banville (London: Pimlico, 2013), xxv, 351pp. [Contents: The pursuit of the ideal; The decline of utopian ideas in the west; Giambattista Vico and cultural history; Alleged relativism in eighteenth-century European thought; Joseph de Maistre and the origins of fascism; European unity and its vicissitudes; The apotheosis of the romantic will: the revolt against the myth of an ideal world; The bent twig: on the rise of nationalism.

- Preface to Best European fiction 2013, ed. & intro. by Aleksandar Hemon; preface by Banville (Champaign, Ill.; London: Dalkey Archive Press 2012), xxiii, 463pp. [contents]

- Ed. & Intro., Elizabeth Bowen, Short Stories (NY: Everyman’s Library, 2019), xlvii, 860pp.

|

| The Wikipedia entry on Banville [online] incls. extensive listings of his reviews and prefaces & introductions - online.; see also numerous prefaces & introductions listed at Library Discover Hub [COPAC] - online; espec. p.3ff; [online]. |

|

| — |

| Banville’s reviews in The New York Review of Books - to April 2007 |

- [...]

- 1 March 2007: Executioner Songs, review of House of Meetings by Martin Amis .

- 21 Dec. 2006: Rainer Maria Rilke and Lou Andreas-Salomé: The Correspondence translated from the German by Edward Snow and Michael Winkler Letters from the Heights; see also replies from John Friedmann and Richard Stern, each taking Banville to task for using the J.B. Leishman trans. of the poems of Rilke (29 March 2007).

- 13 July 2006: In the Luminous Deep - review of Swithering, Slow Air, and A Painted Field by all Robin Robertson.

- 23 Feb. 2006: Homage to Philip Larkin, review of Collected Poems (2003) by Philip Larkin, edited and with an introduction by Anthony Thwaite; First Boredom, Then Fear: The Life of Philip Larkin by Richard Bradford; Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life by Andrew Motion; Collected Poems (1988) by Philip Larkin, edited and with an introduction by Anthony Thwaite; Selected Letters of Philip Larkin, 1940-1985 edited by Anthony Thwaite; Required Writing: Miscellaneous Pieces, 1955-1982 by Philip Larkin.

- 22 Sept. 2005: The Furies, review of Beyond Black by Hilary Mantel.

- 26 May 2005: A Day in the Life, review of Saturday by Ian McEwan; see also John Sutherland, ‘Squash’ [‘I don’t agree with John Banville’s judgment that “Saturday is a dismayingly bad book”] (23 June 2005) [but see also note].

- 16 Dec. 2004: Sentimental Education, review of Villages by John Updike.

- 2 Dec. 2004: The Missing Link, review of Langrishe, Go Down; A Bestiary, and Flotsam & Jetsam, all by Aidan Higgins.

- 8 April 2004: The Sacrifice, review of Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake by Carol Loeb Shloss.

- 11 March 2004: A Double Life, review of Judge Savage by Tim Parks.

- 26 Feb. 2004: The Rescue of W.B. Yeats, review of W. B. Yeats: A Life II: The Arch-Poet 1915-1939 by R.F. Foster.

- 6 Nov. 2003: Good Man, Bad World, review of Orwell: The Life by D. J. Taylor and Inside George Orwell by Gordon Bowker.

- 3 July 2003: Secret Geometry, review of Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Man, the Image and the World with essays by Philippe Arbaïzar, Jean Clair, Claude Cookman, Robert Delpire, Peter Galassi, Jean-Noël Jeanneney, Jean Leymarie, and Serge Toubiana, and with translations from the French by Jane Brenton.

- 15 May 2003: Keeping Busy, review of The Kick: A Memoir by Richard Murphy.

- 10 April 2003: By George, review of Becoming George: The Life of Mrs. W. B. Yeats by Ann Saddlemyer.

- 26 Sept. 2002: On the Fatal Shore, review of Gould’s Book of Fish: A Novel in Twelve Fish by Richard Flanagan.

- 9 May 2002: In the Puddles of the Past, review of Irish Classics by Declan Kiberd and Poetry & Posterity by Edna Longley.

- 14 Feb. 2002: Cowboys and Indians, review of Anthony Blunt: His Lives by Miranda Carter; see also reply by Floyd Abrams [accusing him of exonerating Blunt], with an answer to same (March 14, 2002).

- 4 Oct. 2001: Fathers and Sons, review of The Crisis of Reason: European Thought, 1848-1914 by J.W. Burrow.

- 29 March 2001: The Wild Colonial Boy, review of True History of the Kelly Gang by Peter Carey.

- 8 Feb. 2001: Joyce in Bloom, review of The Years of Bloom: James Joyce in Trieste, 1904-1920 by John McCourt.

- 10 August 2000: Coupling, review of The Married Man by Edmund White; Edmund White: The Burning World by Stephen Barber, and The Boy with the Thorn in His Side: A Memoir by Keith Fleming.

- 27 April 2000: Landscape Artist, review of Microcosms by Claudio Magris, Translated from the Italian by Iain Halliday.

- 13 April 2000: A Rare Species, review of Being Dead by Jim Crace.

- 20 Jan. 2000: Endgame, review of Disgrace by J.M. Coetzee.

- 16 Dec. 1999: The Motherless Child, review James Joyce by Edna O’Brien.

- 18 Nov. 1999: The Tragicomic Dubliner, review No Laughing Matter: The Life and Times of Flann O’Brien by Anthony Cronin, and At Swim-Two-Birds by Flann O’Brien.

- 24 June 1999: The Friend of Promise, review of Cyril Connolly: A Life by Jeremy Lewis.

- 14 Jan. 1999: The Dawn of the Gods, review of Ka: Stories of the Mind and Gods of India by Roberto Calasso, translated by Tim Parks.

- 13 Aug. 1998: The Last Days of Nietzsche, review of Nietzsche in Turin: An Intimate Biography by Lesley Chamberlain; and see also and his own response to several letters, 5 Nov. 1998 [‘ widely accepted-by Thomas Mann, among others-that Nietzsche was syphilitic, in the same sense that while it is not proved that Jesus Christ was crucified, it is generally accepted that he was.’] .

- 20 Nov. 1997: A Life Elsewhere, review of Boyhood: Scenes from Provincial Life by J. M. Coetzee.

- 12 June 1997: The European Irishman, review of Independent Spirit by Hubert Butler.

- 20 Feb. 1997: Revelations, review of Selected Stories by Alice Munro and After Rain by William Trevor.

- 14 Nov. 1996: The Painful Comedy of Samuel Beckett, review of Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett by James Knowlson; Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist by Anthony Cronin; The World of Samuel Beckett, 1906-1946 by Lois Gordon; The Complete Short Prose, 1929-1989 edited by S.E. Gontarski; Eleutheria by Samuel Beckett, translated by Michael Brodsky, and Nohow On: Company, Ill Seen Ill Said, Worstward Ho by Samuel Beckett.

- 4 April 1996: That’s Life!, review of Last Orders by Graham Swift.

- 5 Oct. 1995: Nabokov’s Dark Treasures, review of The Magician’s Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction by Michael Wood.

- 10 Aug. 1995: Nice Work, review of Therapy, and Small World: An Academic Romance both by David Lodge, .

- 6 April 1995: Fish and Roses, review of The Monkey Link: A Pilgrimage Novel by Andrei Bitov, translated by Susan Brownsberger.

- 2 Feb. 1995: The Un-Heimlich Maneuver, review of The Norton Book of Ghost Stories edited by Brad Leithauser, and Women and Ghosts by Alison Lurie.

- 3 Nov. 1994: War Without Peace, review of Generations of Winter by Vassily Aksyonov, translated by John Glad, translated by Christopher Morris [sic] .

- 9 June 1994: A Real Funny Guy, review of The Russian Girl by Kingsley Amis.

- 3 March 1994: Fatal Attraction, review of Cigarettes Are Sublime by Richard Klein.

- 16 Dec. 1993: Writing on Life Support, review of Beckett’s Dying Words by Christopher Ricks, and Dream of Fair to Middling Women by Samuel Beckett.

- 15 July 1993: Living in the Shadows, review of Judge on Trial by Ivan Klíma, translated by A.G. Brain.

- 8 April 1993: Big News from Small Worlds, review of The Collected Stories by John McGahern, and Ulverton by Adam Thorpe.

- 4 March 1993: An Interview with Salman Rushdie.

- 13 Aug. 1992: The Last Word, review of Nohow On: Company, Ill Seen Ill Said, and Worstward Ho all by Samuel Beckett; see also response by Everett C. Frost (5. Nov. 1992).

- 14 May 1992: Playing House, review of A Landing on the Sun by Michael Frayn, and Daughters of Albion by A. N. Wilson.

- 21 Nov. 1991: Winners, review of Jump and Other Stories by Nadine Gordimer, Playing the Game by Ian Buruma, and Asya by Michael Ignatieff.

- 26 Sept. 1991: Relics, review of Two Lives: Reading Turgenev and My House in Umbria by William Trevor.

- 30 May 1991: Slouching Toward Bethlehem, review of Selected Poems by Derek Mahon, and Madoc: A Mystery by Paul Muldoon.

- 14 Feb. 1991: Laughter in the Dark, review of New World Avenue, Vicinity by Tadeusz Konwicki, translated by Walter Arndt, Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal, translated by Michael Henry Heim, and Helping Verbs of the Heart by Péter Esterházy, translated by Michael Henry Heim.

- 6 Dec. 1990: In Violent Times, review of Amongst Women by John McGahern, Lies of Silence by Brian Moore, and The Innocent by Ian McEwan.

- 25 Oct. 1990: Portrait of the Critic as a Young Man, review of Warrenpoint by Denis Donoghue.

- 12 April 1990: Help Salman Rushdie [letter, with others, opposing Iranian fatwa against Salman Rushdie].

|

| Note: In a review of Martin Amis, The House of Meetings (NYRB, 1 March 2007), Banville writes of the ‘ridiculous charges of plagiarism leveled against Ian McEwan for his novel Atonement’. |

| |

| Source: New York Review of Books [online] - Searching <Banville> - Author - 125 [string] - accessed 10.04.2007. |

| Banville’s reviews in the Literary Review (London) - to Sept. 2021 |

| |

|

Sept. 2021 - A Book is Born [diary piece; incls. tribute to Christopher Robbins, The Empress of Ireland, on Brian Desmond Hurst, (film dir.).

July 2020 - The Pragmatist’s Progress - Sick Souls, Healthy Minds: How William James Can Save Your Life.

Dec. 2018 - Quite the Père: Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know: The Fathers of Wilde, Yeats and Joyce, Colm Tóibín.

Sept. 1998 - A Selfish Man Condemned to Live in Ireland: Jonathan Swift, by Victoria Glendinning [see attached].

June 1998 - Secrets of the Oxford English Dictionary: The Surgeon of Crowthorne, by Simon Winchester.

Oct. 1997 - He Discovered the True Philosopher’s Stone: Isaac Newton: The Last Sorcerer, by Michael White.

Feb. 2000 - Scoundrel Manages to Keep his Secrets: Wainewright The Poisoner, by Andrew Motion.

March 2017 - The Master by the Arno [on his relation to Henry James and his new novel - online.]

March 2016 - Sympathy for the Bedevilled: The Astronomer and the Witch, Johannes Kepler’s Fight for His Mother, by Ulinka Rublack.

May 2013 - An Ordinary Rendition: A Delicate Truth, by John le Carré.

Dec. 2013 - An Inspector Calls: Pietr the Latvian, by Georges Simenon (trans. David Bellos); The Late Monsieur Gallet, by Georges Simenon (trans. Anthea Bell); The Hanged Man of Saint-Pholien, by Georges Simenon (trans. Linda Coverdale). |

| —Available at Literary Review - online; accessed 29.01.2024. |

| Best European Fiction 2013, ed. & intro. by Aleksandar Hemon; preface by Banville (Champaign, Ill.; London: Dalkey Archive Press 2012), xxiii, 463pp. CONTENTS [short stories]: ‘Slovakia: Before the breakup’, by Balla; ‘Macedonia. When the glasses are lost’, by Žarko Kujundžiski; ‘Montenegro. The face’, by Dragan Radulović; ‘Georgia. The sins of the wolf/ Lasha Bugadze; ‘Belgium: French. Grand froid’, by Paul Emond --Armenia. The name under my tongue’, by Krikor Beledian; ‘Russia. Last summer in Marienbad’, by Kirill Kobrin; ‘Moldova. Orchestra rehearsal’, by Vitalie Ciobanu; ‘Ireland: Irish. Music in the bone’, by Tomás Mac Síomóin; ‘Finland. My creator, my creation’, by Tiina Raevaara; ‘Hungary. Portrait of a mother in an American frame’, by Miklós Vajda; ‘Turkey: German. Memory cultivation salon’, by Zehra Çirak; ‘Portugal. Angels on the inside /Dulce Maria Cardosa; ‘Latvia.How important is it to be Ernest?’, by Gundega Repše; ‘Ukraine. Me and my sacred cow’, by Tania Malyarchuk; ‘Spain: Castilian. The mercury in the thermometers’, by Eloy Tizón; ‘Boznia and Herzegovina. My heart’, by Semedin Mehmedinović; ‘Austria. A protagonist’s nemesis’, by Lydia Mischkulnig; ‘France. Madame Zabée’s guesthouse’, by Marie Redonnet; ‘Lithuania. The eye of the maples’, by Ieva Toleikytė; ‘Bulgaria. The ragiad’, by Rumen Balabanov; ‘United Kingdom: England. Dolls’ eyes’, by A. S. Byatt; ‘Estonia. The surrealist’s daughter’, by Kristiina Ehin; ‘Poland. It’s all up to you’, by Sylwia Chutnik; ‘Lichtenstein. Malcontent’s monologue’, by Daniel Batliner; ‘Spain: Basque. Pirpo and Chanberlán, murderers’, by Bernardo Atxaga; ‘Serbia. For a foreign master’, by Borivoje Adašević; ‘Slovenia. Nada’s tablecloth’, by Mirana Likar Bajželj; ‘Denmark. Camilla and the horse’, by Christina Hesselholdt; ‘Romania. 7 p.m. wife’, by Dan Lungu; ‘Switzerland. A son’, by Bernard Comment; ‘United Kingdom: Wales. Migration’, by Ray French; ‘Ireland: English. Of one mind’, by Mike McCormack; ‘Iceland. The music shop’, by Gyrðir Elíasson --Norway. Thunder snow and When a dollar was a big deal /Ari Behn. |

| See Discovery Hub Record - online; accessed 29.12.2024. |

[ top ]

Criticism

| Books |

- Rüdiger Imhof, John Banville: A Critical Introduction (Dublin: Wolfhound 1989; rev. edn. 1997) [incl. bibl. of minor writings and novel-extracts].

- Joseph McMinn, John Banville: A Critical Study (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1991) [see extract].

- Laura P. Zuntini de Izarra, Mirrors and Holographic Labyrinths. The Process of a “New” Aesthetic Synthesis in the Novels of John Banville. Lanham, NY & Oxford: International Scholars Publications 1999), 324pp.

- Ingo Berensmeyer, John Banville: Fictions of Order: Authority, Authorship, Authenticity (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter, 2000).

- Derek Hand, John Banville: Exploring Fictions (Dublin: Liffey Press 2002), 188pp.

- John Kenny, ed., John Banville [Irish Writers in Their Time Ser.] (Dublin: IAP 2008), 256pp.

- Neil Murphy, John Banville [Contemporary Writers Ser.] (Bucknell UP 2018), 238pp. [see contents].

|

| Special Issues [IUR] |

- Irish University Review: A Journal of Irish Studies, 11, 1 [‘John Banville Special Issue’, ed. Rüdiger Imhof] (Spring 1981), incls. Imhof, ‘“My Readers, That Small Band, Deserve a Rest”: An Interview with John Banville’, pp.5-12; Banville, ‘A Talk’, pp.13-17; Francis C. Molloy, ‘The Search for Truth’, pp.29-51, et. al.]

- Irish University Review: A Journal of Irish Studies, 36, 1 [‘John Banville Special Issue’, ed. Derek Hand] (Spring/Summer 2006), 256pp. [see contents].

|

| Articles, interviews & reviews |

- Thomas Kilroy, ‘Teller of Tales’, in Times Literary Supplement (17 March 1972), pp.301-02.

- Brian Donnelly, ‘The Big House in the Recent Novel’, in Studies 64 (1975), pp.133-42.

- Seamus Deane, ‘“Be Assured I am Inventing”: The Fiction of John Banville’, in Patrick Rafroidi & Maurice Harmon eds., The Irish Novel in Our Time: Cahiers Irlandaises 4-5 (l’Université de Lille 1976), pp.329-38 [see extract].

- Ronan Sheehan, ‘Novelists on the Novel: Ronan Sheehan Talks to John Banville and Francis Stuart’, in The Crane Bag 3, 1 (1979), pp.76-84.

- Imhof, ‘John Banville’s Supreme Fiction’, pp.52-86; also Imhof, ‘John Banville, A Checklist’, pp.87-95].

- Rüdiger Imhof, ‘The Newton Letter by John Banville: An Exercise in Literary Derivation’, Irish University Review 13, No. 2 (1983), pp.162-67.

- Seamus Deane, Short History of Irish Literature (London: Hutchinson 1986) [see extract].

- Ciaran Carty, ‘Out of Chaos Comes Order’, in The Sunday Tribune (1 Sept. 1986), p.18.

- Geert Lernout, ‘Looking for Pure Visions’, in Graph 1 (Oct. 1986), pp.12-16.

- Joseph McMinn, ‘Reality Refuses to Fall into Place’, in Fortnight (Oct. 1986), p.24.

- David McCormick, ‘John Banville, Literature as Criticism, in Irish Review 2 (1987), pp.95-99.

- Rüdiger Imhof, ‘German Influences on John Banville and Aidan Higgins’, in Wolfgang Zach & Heinz Kosok eds., Literary Interrelations: Ireland, England and the World, II: Comparison and Impact (Tubingen: Gunter Narr, 1987), pp.335-47.

- Rüdiger Imhof, ‘Swan’s Way, or Goethe, Einstein, Banville: The Eternal Recurrence’, Études Irlandaises 12, 2 (Dec. 1987), pp.113-29.

- Rüdiger Imhof, ‘Q & A with John Banville’, in Irish Literary Supplement (Spring 1987), p.13.

- Richard Kearney, ‘John Banville’, Transitions (Dublin: Wolfhound 1987), pp.91-100.

- Joseph McMinn, ‘An Exalted Naming: The Poetical Fictions of John Banville’, in Canadian Journal of Irish Literature 14, 1 (July 1988), pp.17-27.

- Geert Lernout, ‘Banville and Being: The Newton Letter and History’, in Joris Duytschaever and Lernout, eds., History and Violence in Anglo-Irish Literature (Amsterdam: Rodopi 1988), pp.67-77.

- Richard Kearney, ‘A Crisis of Fiction: Flann O’Brien, Francis Stuart, John Banville’ [chap.], in Transitions: Narrative of Modern Irish Culture (Manchester UP 1988), [q.pp.]

- James M. Cahalan, The Irish Novel: A Critical History (Boston: Twayne 1988), pp.277-78.

- Dorinda Outram, ‘Heavenly Bodies and Logical Minds’, in Graph [4] (Spring 1988), pp.9-11.

- Joseph McMinn, ‘Stereotypical Images of Ireland in John Banville’s Fiction’, in Éire-Ireland 23, 3 (Fall 1988), pp.94-102.

- Rüdiger Imhof, John Banville: A Critical Introduction (Dublin: Wolfhound Press 1989).

- Fintan O’Toole, ‘Stepping into the Limelight - and the Chaos’, Irish Times (21 Oct. 1989) [q.p.].

- Anthony McGonagle, ‘The Big House in John Banville’s Fiction’ (M.A. thesis, UUC Jordanstown 1989).

- Neil Cornwell, The Literary Fantastic: From Gothic to Postmodernism (New York: Harvester/London: Wheatsheaf 1990), pp.172-84.

- Terence Brown, ‘Redeeming the Time, the Novels of John McGahern and John Banville’, in James Acheson ed., The British and Irish Novel Since 1960 (London: Macmillan 1991), pp.159-73.

- Gearóid Cronin, ‘John Banville and the Subversion of the Big House Novel’, in J. Genet, ed., The Big House in Ireland (Dingle: Brandon 1991), pp.251-60.

- Sean Lysaght, ‘Banville’s Tetralogy: The Limits of Mimesis’, in Irish University Review 21 (Spring/Summer 1991), pp. 82-100.

- Joseph McMinn, ‘“Naming the World: Language and Experience in John Banville’s Fiction’, in Irish University Review 23 (Autumn/Winter 1993), pp. 183-96.

- Joseph Swann: “Banville’s Faust”, in onald .E. Morse, Csilla Bertha & I. Palffy, eds., A Small Nation’s Contribution to the World: Essays on Anglo-Irish Literature and Language (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe; Debrecen: Lajos University 1993), pp.148-60.

- John Devitt, ‘Early Banville’, review of Nightspawn, The Book of Evidence and Ghosts , in Irish Literary Supplement 13, 1 (Spring 1994), p.36.

- John Dunne, ‘Fiction’s Own Laws,’ review of Nightspawn (1971), in Books Ireland (Sept. 1994), pp.201-02.

- Mark Wormald, review of Athena, in Times Literary Supplement (10 Feb 1995), p.19.

- Amanda Craig review of Athena, Times (16 Feb 1995).

- Patricia Craig, ‘This is Such Stuff as Dreams are Made On’, review of Athena, in Spectator (18 Feb. 1995), p.30 [see extract].

- John Dunne, ‘Weird or What?’, review of Athena [with novels by John McKenna and Gaye Shortland], in Books Ireland (April 1995), pp.81-83 [see extract].

| Reviews of Athena (1995) |

Boston Globe (23 May 1995), p.76.

Los Angeles Times / Book Reviews (2 July 1995), p.11.

New Statesman and Society, VIII (17 Feb 1995), p.38.

New York Times / Book Reviews, C (21 May 1995), p.15.

The New Yorker, LXXI (31 July 1995), p.79.

The Observer (19 Feb 1995), p.18.

The Spectator, CCLXXIV (18 Feb. 18 1995), p.30.

Times Literary Supplement(10 Feb. 1995), p.19.

Washington Post / Book World, XXV (9 July 1995), p.1.

|

| —Noticed in Endnotes.com online; accessed 24.07.2011. |

|

- Robert Tracy, ‘The Broken Lights of Irish Myth’, review of The Broken Jug, in Irish Literary Studies (Fall 1995), p.18 [see extract].

- Hedwig Schall, ‘An Interview with John Banville’ [Shelbourne Hotel, Sat. 18th Dec. 1996], in The European English Messenger [ESSE], VI, No.1 (Spring 1997), pp.13-19.

- Vera Kreilkamp, ‘Reinventing a Form: Aidan Higgins and John Banville’, in The Anglo-Irish Novel and the Big House (NY: Syracuse UP 1998), pp.234-60 [Chap. 9].

- William Trevor, ‘Surfaces Beneath Surfaces’, review of The Untouchable, in Irish Times (26 April 1997) [see extract].

- Frederick Raphael, ‘The Sensitive Plant’, review of The Untouchable, in Independent [UK] (26 April 1997).

- Maggie Gee, review of The Untouchable, in Times Literary Supplement (9 May 1997), p.20 [see extract].

- Chris Petit, ‘Autopsy of Englishness’, review of The Untouchable, Guardian Weekly (18 May 1997) [see extract].

- John Bayley, ‘The Double Life’, review of The Untouchable, in NY Review of Books (29 May 1997), pp.17-18.

- Frank Kermode, ‘Gossip’, review of The Untouchables [sic], in London Review of Books (5 June 1997), p.23 [see extract].

- Liam Fay, ‘The Touchable’ [interview with Banville], Hot Press, 21, 13 (9 July 1997), pp.44-46.

- Hedwig Schwall, ‘An Interview with John Banville’, in The European English Messenger, VI, 1 (Spring 1997), pp.13-19.

- M. Keith Booker, ‘Cultural Crisis Then and Now: Science, Literature, and Religion in John Banville’s Doctor Copernicus and Kepler’, in Critique, 39, 2 (1998), pp.176-92.

- Joseph McMinn, The Supreme Fictions of John Banville (Manchester UP 1999), 220pp. [reviewed by Kevin Keily in Books Ireland (Feb. 2000), p.19].

- Ruth Frehner, The Colonizers’ Daughters: Gender in The Anglo-Irish Big House Novel (Tubingen: Franacke 1999), x, 256pp.

- Christopher Taylor, reviewing John Banville, Eclipse, in Times Literary Supplement, 29 Sept. 2000) [see extract].

- John Kenny, ‘The Ideal Elegies’, review of The Revolutions Trilogy: Doctor Copernicus, Kepler, The Newton Letter [rep. edns.], in The Irish Times, 6 Jan. 2001 [see extract].

- Laura P. Zuntini di Izarra, Mirrors and Holographic Labyrinths: The Process of a New Synthesis in the Novels of John Banville (SF: Internat. Scholars Publ. 1999), 181pp. [see review by Hedwig Schwall, in Irish Studies in Brazil (SP: Assoc. Editorial Humanitas 2005), p.253ff.]

- Conor McCarthy, ‘Irish Metahistories: John Banville and the Revisionist Debate’ [Chap. 2], in Modernisation: Crisis and Culture in Ireland 1969-1992 (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2000), pp.80-134.

- Carlo Gébler, review of The Untouchable, in Fortnight [q.d.], p.31 [see extract]. James Wood, reviewing Eclipse, in The Irish Times [Weekend] (16 Sept. 2000) [see extract].

- Declan Kiberd, ‘The Art of Science: Banville’s Doctor Copernicus’, in Irish Fiction since the 1960s: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Elmer Kennedy-Andrews (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2002) [Chap. 8].

- Joseph McMinn, ‘Ekphrasis and the Novel: The Presence of Paintings in John Banville’s Fiction.’, in Word and Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry, 18, 2 (2002), pp.137-45.

- Ib Johansen, ‘Shadows in a Black Mirror: Reflections on the Irish Fantastic from Sheridan Le Fanu to John Banville’, in Nordic Irish Studies, ed. Michael Böss & Irene Gilsenan Nordin, 1, 1 (2002), pp.51-62 [see copy - as attached].

- Victoria Stewart, ‘;“;I May Have Misrecalled Everything”;. John Banville’s The Untouchable’, in English, 52 (Autumn 2003), pp237-25.

- Robin Wilkinson, ‘Echo and Coincidence in John Banville’s Eclipse’, in Irish University Review, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Autumn/Winter 2003), pp.356-70.

- Brendan MacNamee, ‘A Rosy Crucifixion: Imagination and Time in John Banville’s Birchwood’, in Studies (Spring 2003) [q.p.; extract].

- Monica Facchinello. ‘Sceptical Representations of Home: John Banville’s Doctor Copernicus& Kepler, in Global Ireland: Irish Literatures for the New Millenium, ed. Ondrej Pilny & Clare Wallace [IASIL Conference 2004] (Prague: Litteraria Pragensia 2005), pp.109-21.

- Neil Murphy, Irish Fiction and Postmodern Doubt - An Analysis of the Epistemological Crisis in Modern Irish Fiction (Edwin Mellen Press 2004), 286pp. [Chap. 3: John Banville - Out of the Postmodern Abyss].

- Anja Müller, ‘“You Have Been Framed’: The Function of Ekphrasis for the Representation of Women in John Banville’s Trilogy (The Book of Evidence, Ghosts, Athena)’, in Studies in the Novel, 36, 2 (Summer 2004), pp.185-205.

- John Kenny, ‘What Lies Beneath’, review The Sea, in The Irish Times (28 May 2005) [see extract].

- [...]

- Joanne Watkiss, ‘Ghosts in the Head: Mourning, Memory and Derridean “Trace” in John Banville’s The Sea’, in The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies, 2 (March 2007) [see extract].

- John Kenny, ‘;John Banville’, in Visions and Revisions: Irish Writers in their Time, ed. Stan Smith (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2009) [q.pp.; Chap. 3.]

- Laura Miller, ‘Oh Gods’, review of The Infinities by John Banville, in The New York Times, Sunday Book Review (7 March 2010) [see extract]

- Janet Maslin, ‘Gods Are in Their Heaven, but All’s Not Right With World’, review of The Infinities by John Banville, with Elegy for April by Benjamin Black [John Banville], in The New York Times, Books of the Times (4 April 2010) [see extract]

- John Boyne, ‘The World and Its Wicked Ways’, review of A Death in Summer, in The Irish Times(4 June 2010), Weekend Review, p.10 [see extract].

- Sara Keating, ‘All artists think they are gods,[...].’ [interview with John Banville], in The Irish Times (4 June 2011), [see extract].

- Declan Burke, interview with Banville, in Down These Green Streets: Irish Crime Writing in the 21st Century, ed. Burke (Dublin: Liberties Press 2011) [see extract].

- Arminta Wallace, ‘I’m at last beginning to learn how to write, and I can let the writing mind dream’: interview with Banville, in The Irish Times (30 June 2012), Weekend Review, p.7 [see extract].

- Karl Miller, “So Here’s To You, Mrs. Gray”, review of Ancient Light, by John Banville, in The Irish Times (7 July 2012), Weekend Review, p.11 [see extract].

- Christopher Benfey, “Doubling Back”, review of Ancient Light, by John Banville, in The New York Times (9 Nov. 2012), “Books” [see extract].

- Jon Wiener, ‘I Hate Genre: Q & A - an Interview with John Banville / Benjamin Black’, in Los Angeles Review of Books (14 March 2014), 3/15 [available online].

- Bevin Doyle, Indestructible Treasures: Art and the Ekphrastic Encounter in selected novels by John Banville [PhD Diss.] (Dublin City University [DCU] 2015) - available online [accessed 12.10.2025].

- Neil Murphy, ‘John Banville: The City as Illuminated Image’, in Irish Urban Fictions, ed., Maria Beville & Deirdre Flynn [Lit. Urban Studies Ser.] (London: Palgrave 2018), pp.167-82.

- Alvaro Costa e Silva, ‘Personagens de John Banville são monstros admiráveis’, review of Book of Evidence as O livro de Evidencias, in Folha de São Paulo (21 July 2018)- online.

- Pietra Palazzolo, Michael Springer & Stephen Butler, eds., John Banville and His Precursors (London: Bloomsbury Publishing 2019), 256pp. [see contents].

- Alisa Hemphill, ‘I Am, Therefore I Think: Being and Thinking Inside the World of John Banville’s Fiction’, in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Contemporary British and Irish Literature, ed. Richard Bradford, et al. (Oxford; John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 2020), pp.139-48 [Chap. 14].

|

| |

See also Rüdiger Imhof, ed., Contemporary Irish Novelists (Tübingen: Gunther Narr 1990); Vera Kreilkamp, Anglo-Irish Novel and the Big House (Syracuse UP 1998; Eurospan 1999) [as supra], and Eve Patten on the British Council’s Contemporary Writers website [link; defunct in 2024]. |

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Neil Murphy, John Banville [Contemporary Irish Writers] ([Lexington:] Bucknell UP 2018), xiv; Introduction [1-26]; 1. The Early Evolution of an Aesthetic: From Long Lankin to Mefisto [27-62]; 52. The Frames Trilogy: The Book of Evidence, Ghosts, and Athena [63-92]; 3. Brushstrokes of Memory: The Sea [93-118]; 4. The Art of Self-Reflexivity: The Cleave Novels [119-38]; 5. John Banville and Heinrich von Kleist - The Art of Confusion: The Broken Jug, God’s Gift, Love in the Wars, and The Infinities [139-58]; 6. Art and Crime: Benjamin Black’s Quirke Novels [159-86]; Conclusion [187-200]; Bibliography [201-10]. Index [211-214] About the Author [215-216].

| Irish University Review: A Journal of Irish Studies, 36, 1 [‘John Banville Special Issue’, ed. Derek Hand] (Spring/Summer 2006), 256pp. CONTENTS: Derek Hand, Introduction: ‘John Banville’s Quixotic Humanity’ [viii-xii]; John Banville, ‘A World Too Wide ’ [1-8]; Neil Murphy, ‘From Long Lankin to Birchwood: The Genesis of John Banville’s Architectural Space’ [9]; Brian McIlroy, ‘Theory, Science, and Negotiation: John Banville’s Doctor Copernicus’ [25]; Kersti Tarien Powell, ‘The Lighted Windows: Place in John Banville’s Novels’ [39]; John Kenny, ‘Well Said Well Seen: The Pictorial Paradigm in John Banville’s Fiction’ [52]; Elke D’hoker, ‘Self-Consciousness, Solipsism, and Storytelling: John Banville’s Debt to Samuel Beckett [68]; Patricia Coughlan, ‘Banville, the Feminine, and the Scenes of Eros’ [81]; Eibhear Walshe, ‘“A Lout’s Game”: Espionage, Irishness, and Sexuality in The Untouchable’ [102]; Hedwig Schwall, ‘“Mirror on Mirror Mirrored Is All the Show”: Aspects of the Uncanny in Banville’s Work with a Focus on Eclipse’ [116]; Joseph McMinn, ‘“Ah, This Plethora of Metaphors! I Am like Everything Except Myself”: The Art of Analogy in Banville’s Fiction’ [134]; Hedda Friberg, ‘“[P]assing through Ourselves and Finding Ourselves in the Beyond”: The Rites of Passage of Cass Cleave in John Banville’s Eclipse and Shroud’ [151; Rüdiger Imhof, ‘The Sea: “Was’t Well Done?”’ [165]; Laura P. Z. Izarra, ‘Disrupting Social and Cultural Identities: A Critique of the Ever-Changing Self’ [182]; Hedda Friberg, ‘John Banville and Derek Hand in Conversation’ [200]; Rüdiger Imhof, ‘John Banville: A Select Bibliography’ [216-36]. Book Reviews: Christopher Murray, review of Diarmuid and Grania: Manuscript Materials by W. B. Yeats, George Moore, b J. C. C. Mays [238]; Mária Kurdi, review of Identities in Irish Literature, by Anne MacCarthy [241]; Graham Price, review of The Faiths of Oscar Wilde: Catholicism, Folklore and Ireland, by Jarlath Killeen [244]; Helen O’Connell, review of Victoria’s Ireland? Irishness and Britishness, 1837-1901, by Peter Gray [248]; Claudia Calavetta, review of Studi Irlandesi by Carlo Bigazzi [251-53]. |

| Associação Brasileira de Estudos Irlandeses, USP [Univ. de Sao Paolo / USP ) |

| ABEI Journal, 22:1 [Special Issue: “Word Upon World: Half a Century of John Banville’s Universes”, guest eds., Laura P.Z. Izarra, Hedwig Schwall, Nicholas Taylor-Collins; (São Paolo 2020) - CONTENTS: Izarra, Schwall, Taylor-Collins, Introduction, pp.15-17; Juan José Delaney, ‘The Crafting of Art – Translating Worlds: The Short Story Narrative Form According to John Banville’ [23]; Alan Gilsenan, ‘John Banville: “The Weightless Density of a Dream”’ [27]; Neil Hegarty, ‘Plate Tectonics' [31]; Patrick Holloway, ‘How Banville Makes the Banal Beautiful’ [33]; Rosemary Jenkinson, ‘Alive and Tricking – John Banville and Paul Auster’ [35]; Colum McCann, “John Banville” [39]; Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, “Banville and Black” [41]; Annemarie Ní Churreáin, “Time Pieces: A Dublin Memoir: An Ode To the Act of Dreaming’ [43]; Billy O’Callaghan, ‘Reflecting on discovering John Banville as a young reader’ [45]; John O’Donnell, ‘Unsworn Statement – The Artful Testimony of The Book of Evidence’ [49]; Jessica Traynor, ‘The Cage Door Open: Depictions of Monstrosity in Banville and Shakespeare’ [53]; Adel Cheong, ‘Critical Dialogues Familiar/Familial Strangeness: The Place of Narration in John Banville’s Eclipse and The Sea and Mike McCormack’s Solar Bones’ [61]; Hedda Friberg-Harnesk, ‘“High Stakes” in the Symbolic Order: John Banville’s Love in the Wars Read through Jean Baudrillard’ [75]; Cody D. Jarman, ‘Famine Roads and Big House Ghosts: History and Form in John Banville’s The Infinities’ [85]; Lianghui Li, ‘Simultaneous Past and Present in The Sea' [97]; Neil Murphy, ‘The Poetics of “Pure Invention”: John Banville’s Ghosts’ [109]; Aurora Piñeiro, ‘Postmodern Pastiche: The Case of Mrs Osmond by John Banville’ [121]; Kersti Tarien Powell, ‘“Cancel, yes, cancel, and begin again”: John Banville’s Path from ‘Einstein” to Mefisto’ [135]; Hedwig Schwall, ‘Banville and Lacan: The Matter of Emotions in The Infinities’ [147]; Nicholas Taylor-Collins, ‘Ageing John Banville: from Einstein to Bergson’ [159]; Catherine Toal, ‘Misanthropy of Form: John Banville’s Henry James’ [173]; Joakim Wrethed, ‘“Cloud’s red, earth feeling, sky that thinks”: John Banville’s Aesth/ethics’ [183]; Jorge Schwartz, ‘Voices from South America: Let The Stars Compose Syllables Xul and Neo-Creole’ [199-228]. Book Reviews: David Clark on The Secret Guests [229]; Adel Cheong on Neil Murphy, John Banville [233]; Mehdi Ghassemi on Hedda Friberg-Harnesk, Reading John Banville through Jean Baudrillard [237-38]. |

| —Available online; accessed 30.12.2024. |

Pietra Palazzolo, Michael Springer & Stephen Butler (London: Bloomsbury Publishing 2019), 256pp. CONTENTS: Pietra Palazzolo, Michael Springer & Stephen Butler (London: Bloomsbury Publishing 2019), 256pp. CONTENTS: Michael Springer, Introduction. Part I - National and transnational currents: 1. Derek Hand, ‘John Banville and the idea of the precursor: some meditations’; 2. Peter Boxall, ‘Unknown unity: Ireland and Europe in Beckett and Banville’. Part II - Literary Engagements: 3. Darren Borg, ‘“The vain thing menaced by the touch of the real”: John Banville as a precursor to Henry James’; 4. Elke D’hoker, ‘From Isabel Archer to Mrs Osmond: John Banville reinterprets Henry James’; 5. Pietra Palazzolo, ‘Afterlives of a supreme fiction: John Banville’s dialogue with Wallace Stevens’; 6. Rebecca Downes, ‘Effacing the subject: Banville, Kleist and a world without people’; 7. Michael Springer, ‘The limits of simile: Rilke, Stevens, and Banville’s scepticism’; 8. Joakim Wrethed, ‘John Banville and Hugo von Hofmannsthal: language, mundane revelation, and profane sacrality’. Part III - Philosophical, theoretical, and artistic forebears. 9. Karen McCarthy, ‘“A fool’s errand”: Blanchot, mourning, and The Sea’; 10. Mehdi Ghassemi, ‘Reading Banville with Lacan: hysteric aesthetics in The Book of Evidence’; 11. Stephen Butler, ‘Existential precursors and contemporaries in Banville’s Alex Cleave trilogy’; 12. Michael Springer, ‘“An earthly glow”: Heidegger and the uncanny in Eclipse and The Sea’; 13. Neil Murphy, ‘John Banville’s ekphrastic experiments’.

[ See EFACIS “John Banville Bibliography ”- online, or open copy as attached.]

| A Banville Bibliography extracted from Christopher James Thomson, “Powers of misrecognition”: Masculinity and the Politics of the Aesthetic in the Fiction of John Banville [PhD thesis] (Canterbury Univ. 2008). |

- Ingo Berensmeyer, John Banville: Fictions of Order: Authority, Authorship, Authenticity (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter, 2000).

- Anja Muller, ‘“You Have Been Framed֨: The Function of Ekphrasis for the Representation of Women in John Banville’s Trilogy (The Book of Evidence, Ghosts, Athena)’, in Studies in the Novel, 36, 2 (2004), pp.185-205.

- M. Keith Booker, ‘Cultural Crisis Then and Now: Science, Literature, and Religion in John Banville’s Doctor Copernicus and Kepler’, in Critique, 39, 2 (1998), pp.176-92.

- Françoise Canon-Roger, ‘John Banville’s Imagines in The Book of Evidence’’, in European Journal of English Studies, 4, 1 (2000), pp.25-38.

- Patricia Coughlan, ‘Banville, the Feminine, and the Scenes of Eros.’ Irish University Review, 36, 1 (2006), pp.81-101.

- Elke D’hoker, ‘Books of Revelation. Epiphany in John Banville’s Science Tetralogy and Birchwood’, in Irish University Review (2000), pp.32-50.

- —, ‘Negative Aesthetics in Hugo Von Hofmannsthal’s Ein Brief and John Banville’s the Newton Letter, in New Voices in Irish Criticism: 3, ed. Karen Vandevelde (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2002), pp.36-43.

- —, Visions of Alterity: Representation in the Works of John Banville [Costerus New Series 151], ed. C.C. Barfoot, Theo D’haen and Erik Kooper (Amsterdam: Rodopi 2004).

- —, ‘“What Then Would Life Be but Despair?”: Skepticism and Romanticism in John Banville’s Doctor Copernicus’, in Contemporary Literature, 45, 1 (2004), pp.49-78.

- De Schutter, Dirk. ‘Revolting Revolution: On John Banville’s Doctor Copernicus’, in Sense and Transcendence: Essays in Honour of Herman Servotte, ed. Ortwin de Graef, et al. (Leuven [Louvain] UP 1995), pp.141-61.

- Derek Hand, John Banville: Exploring Fictions (Dublin: Liffey Press 2002).

- Joseph McMinn, ‘Ekphrasis and the Novel: The Presence of Paintings in John Banville’s Fiction.’, in Word and Image, 18, 2 (2002), pp.137-45.

- Liam Heaney, ‘Science in Literature: John Banville’s Extended Narrative’, in Studies: an Irish Quarterly Review, 85, 340 (1996), pp.362-69.

- Rudiger Imhof, ‘German Influences on John Banville and Aidan Higgins’, in Literary Interrelations: Ireland, England and the World, Vol. 2: Comparison and Impact, ed. Wolfgang Zach & Heinz Kosok (Tübingen: Narr 1987), pp.335-47.

- —. ‘John Banville’s Supreme Fiction’, in Irish University Review, 11, 1 (1981), pp.52-86.

- —. John Banville: A Critical Introduction (Dublin: Wolfound Press 1989).

- —. ‘Swan’s Way; or, Goethe, Einstein, Banville: the Eternal Recurrence’, in Études Irlandaises: Revue Française d’Histoire, Civilisation et Littérature de l’Irlande, 12.2 (1987b), pp.113-29.

- Vera Kreilkamp, ‘Reinventing a Form: Aidan Higgins and John Banville.’, in The Anglo-Irish Novel and the Big House [Irish Studies] (NY: Syracuse UP 1998), pp.234-60.

- —. The Supreme Fictions of John Banville (Manchester: Manchester UP 1999.

- Joseph McMinn, ‘Ekphrasis and the Novel: The Presence of Paintings in John Banville’s Fiction’, in Word and Image, 18, 2 (2002), pp.137-45.

- Neil Murphy, ‘From Long Lankinto Birchwood: The Genesis of John Banville’s Architectural Space’, in Irish University Review, 36, 1 (2006), pp.9-24.

- Hedwig Schwall, ‘An Interview with John Banville.’, in European English Messenger, 6, 1 (1997), pp.13-19.

- Joanne Watkiss, ‘Ghosts in the Head: Mourning, Memory and Derridean “Trace” in John Banville’s The Sea’, in Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies, 2 (2007) [q.pp.]

- Kim L. Worthington, ‘A Deviant Narrative: John Banville’s Book of Evidence’, in Self as Narrative: Subjectivity and Community in Contemporary Fiction, ed. Christopher Butler, et al. [Oxford English Monographs] (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1996), q.pp..

|

| Available at Canterbur University - online. |

[ See also num. reviews not listed above but given as extracts under Commentary - as infra. ]

[ top ]

References

| Try these .... |

- Tim Conley on Banville at Modern Word Scriptorium - online; accessed in 2007]

- Eve Patten on Banville at Contemporary Writers - online; accessed in 2007]

|

| —Ah, Mortality! ... both defunct by 2024. |

|

Kate O’Brien Weekend (2009) - notice on Banville [adapted]: Literary Editor of the Irish Times, 1988-99, he first issued Long Lankin (1970), short stories, followed by Nightspawn (1971) and Birchwood (1973), both novels, and next published a series of fictional portraits of eminent scientists beginning with the 15th-century Polish astronomer Dr Copernicus (1976), winner of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction, followed by a novel about the 16th-century German astronomer Kepler (1981), which took the Guardian Fiction Prize, and -finally - The Newton Letter: An Interlude (1982), the story of an academic writing a book on Sir Isaac Newton which was was adapted as a C4 TV film. His next novel, Mefisto (1986), is a reworking of Dr Faustus and an exploration of the world of numbers. His next novel, The Book of Evidence (1989), which is narrated by Freddie Montgomery, a character based on the contemporary case of Malcolm Macarthur, won the Guinness Peat Aviation Book Award and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Fiction. Ghosts (1993) and Athena (1995) are sequels dealing with the same character after release. Victor Maskell, the central character of his next novel, The Untouchable (1997), is based on the upper-crust Engliah art-historian and Soviet spy Anthony Blunt - the eponymous ‘third man’. Eclipse (2000) is narrated by Alexander Cleave, an actor who has withdrawn to the house where he passed his childhood; Shroud (2002), continues his story. The Sea (2005), beingthe narrative of an elderly art historian who loses his wife to cancer and feels compelled to revisit the seaside villa where he spent family holidays in childhood, took the 2005 Man Booker Prize for Fiction. Prague Pictures: Portrait of a City (2003), is a personal evocation of that city.

[ top ]

Anthologies

Peter Fallon & Seán Golden, eds., Soft Day: A Miscellany of Contemporary Irish Writing (Dublin: Wolfhound Press; US: Notre Dame 1980), contains ‘Fragment from a Novel in Progress [Kepler ]’, pp.170-76.

Andrew Carpenter & Peter Fallon, eds., The Writers: A Sense of Place (Dublin: O’Brien Press 1980), contains extract from Kepler ; incls. photo-portrait.

Booksellers

Peter Ellis (Cat. 20) lists Long Lankin (London: Martin Secker & Warburg 1970), 189pp., first novel; £450 [in 2004]; Eclipse (2000) [£20].

[ top ]

Notes

Birchwood (1873); the novel centres around Gabriel Godkin and his return to the dilapidated family estate after years of absence. Delving deep into a family legacy of memories and despair embodied by the house itself, he reveals to the reader the tortuous experience of Irish history - strangely delivered in an anachronistic tale of conquest and plantation, famine and Land War, all embodied in the interlocking characters of a cold father, a tortured mother and an insane grandmother. Gabriel personal progress from innocence to experience, involving a hallucinatory journey with a troupe of circus players, matches sexual intimacies with political violence in a plot the ends cataclysmically with the burning of the house itself. The whole is conveyed in an intensely stylised prose whcih suggests the manner of magic realism, reaching beyond the naturalistic into the domain of symbol and correspondence without lapsing into mere fantasy or pastiche. (See www.goodreads.com online - accessed 24.07.2011.)

Copernicus (1976): The novel, which is filled with a sense of the historical reality of the period, follows the astronomer’s life from childhood to death in four distinct parts. The first part, “Orbitas lumenque” is a narrative of childhood and education in Prussia and Italy. The second part deals with Copernicus’s traumatic relationship with his brother; the third part, using Banville’s technique of mixing time and characters, gives us version of events by his disciple Rheticus who finally secured publication of Copernicus’s work but became completely cynical and morally exhausted in the process; the final part, “Magnum miraculum”, hands the novel back to the narrator andf gives us Banville’s interpretation of Faustian myth in relating the mental and physical decline of the astronomer. (See Nataliya Stokes, ‘The Concept of Harmony in Selected Works of John Banville’, BA Hons. Dissertation, UUC 2005.)

Athena (1995): third in a trilogy which follows the protagonist, Mr. Morrow, a man of contradictory sensibility yearning equally for gothic monsters and pristine world of artistic perfection as he wanders through the realm of art and the criminal underworld. The novel opens with a homage to his love, A. and an account of the ominous house where he meets a sinister pair one of whom (Morden) proposes that he catalogue eight Flemish paintings in his possession. For the rest of the novel, the narrative chapters are interspliced with others analysing the eight paintings. On his second trip through the neighborhood, Morrow is invited by striking woman into her room at the same house and begins a steamy romance with her. Later, Morden takes him to meet a man called “the Da”, a master-criminal and the major force behind the theft and the cataloging of the paintings. In a minor plot, Morrow’s elderly cousin Aunt Corky leaves her her estate to him after long illness. When Detective Hackett, a police inspector, arrives in quest of the stolen paintings Morrow confesses that they are hidden in the house, and later it is discovered that all but one are forgeries. When the Da, Morden, and A. all disappear, Detective Hackett informs Morrow that Morden and A. are the Da’s children, leading Morrow to understand that his involvement with A was contrived to draw him into the crime. Morrow embarks on a search for A and an examination of his experiences related in the novel. The whole revisits and develops the themes of identity and authenticity, order, intelligibility and mythology in the modern life. (BS: see www.endnotes.com online; accessed 24.07.2011.)

God’s Gift (2000) is a bawdy tale based on Heinreich Von Kleist’s 1807 version of the myth of Prince Amphitryon whose wife is seduced by Jupiter, now set in Ireland following the 1798 Rebellion with General Ashburningham’s Minna, with a subplot concern Jupiter’s interference with the General’s servant Souse and his wife Kitty; produced by Barabbas (dir. Veronica Coburn). See Irish Emigrant Arts Review (Dec. 2000).

Seachange (Autumn 1994), his first TV drama, appeared in RTÉ “Two Lives” series; produced by Focus Th. along with Michael Harding, Kiss [see Irish Times, 19 Nov. 1994].

The Sea (2005): a man who has recently lost his wife returns to the seaside village of his childhood, mixing memories of marriage with those of a childhood infatuation; a novel of love and time, and the influence of the past. It begins: ‘They depart, the gods, on the day of the strange tide.’

Christine Black (2006): In the Pathology Department it was always night. This was one of the things Quirke liked about his job ... it was restful, cosy, one might almost say, down in these depths nearly two floors beneath the city’s busy pavements. There was too a sense here of being part of the continuance of ancient practices, secret skills, of work too dark to be carried on up in the light. But one night, late after a party, Quirke stumbles across a body that shouldn’t have been there...and his brother-in-law, eminent paediatrician Malachy Griffin - a rare sight in Quirke’s gloomy domain - altering a file to cover up the corpse’s cause of death. It is the first time Quirke encounters Christine Falls, but the investigation he decides to lead into the way she lived - and the reason she died - disturbs a dark secret that has been festering at the core of Dublin’s high Catholic society, a secret ready to destabilize the very heart and soul of Quirke’s own family ... [see COPAC online; accessed 31.07.08]

[ top ]

The Silver Swan (2007): Time has moved on for Quirke, the world-weary Dublin pathologist first encountered in Christine Falls. It is the middle of the 1950s, that low, dishonourable decade; a woman he loved has died, a man whom he once admired is dying, while the daughter he for so long denied is still finding it hard to accept him as her father. When Billy Hunt, an acquaintance from college days, approaches him about his wife’s apparent suicide, Quirke recognises trouble but, as always, trouble is something he cannot resist. Slowly he is drawn into a twilight world of drug addiction, sexual obsession, blackmail and murder, a world in which even the redoubtable Inspector Hackett can offer him few directions. [See COPAC online; accessed 31.07.08]

Elegy for April (2010): set in 1950s Ireland; newly returned from a drying-out hospital, is set to investigate the disappearance of the young woman in the title whose friend Phoebe Griffin, haunted by the horrors of her past, calls on Quirke’s daughter’s help. Assisted by Inspector Hackett, Quirke discovers that the missing girl’s family is anxious to suppress the scandal associated with her disappearance. More seems to lie behind the missing girl’s habitual secrecy than meets the eye. Quirke is led astray - and back to drinking - by a beautiful young actress while Phoebe watches on helplessly as April’s family hush up her disappearance. Only the unthinkable seems to explain her disappearance; and when Quirke makes a disturbing discovery he begins to unravel the complex web of love, lies, jealousy and dark secrets out of which April’s life was spun. (See COPAC online; accessed 30.07.2011.)

Elegy for April (2010) [cont.:] features Dublin pathologist Dr Quirke, Banville’s uncompromising sleuth; opens in 1950s Dublin with the city shrouded in a “muffled silence” of fog where it “seemed bewildered, like a man whose sight has suddenly failed”, and sustains the imagery of inclement weather throughout the novel in the form of an acutely apposite metaphor for a society held tightly in the grip of reactionary individuals and cabals hiding behind self-serving facades of respectability. We first meet Quirke drying out in St John of God’s; struggling with “the daily unblurred confrontation with a self he heartily wished to avoid”; when he lapses the whiskey gives him “the feeling of it spreading through his chest made him think of a small, many-branched tree bursting slowly into hot, bright flames”; obliged by the programme to expose his failures to a “designated fellow-sufferer”, one Harkness, a Christian Brother who represents the institutionalised world in which Quirke spent his maimed childhood, but Harkness is only able to “release reluctant resistant nuggets of information, as if he were spitting out the seeds of a sour fruit”. Quirke is visited by his daughter Phoebe who whom he previously gave away after the death of her mother; she confides her concerns about a missing friend April Latimer, the estranged daughter of the powerful Latimer family who do their best to frustrate his search by means of “the velvet word, the silken threat”. Other characters incl. the thin lipped (warm-hearted) Inspector Hackett, and Isabel Galloway, an actress and Quirke’s love interest whose “vivid lips, sharply curved and glistening, [...] looked as if a rare and exotic butterfly had settled on her mouth and clung there, twitching and throbbing”. David Park, reviewing, remarks on the numerous Dickensian echoes and allusions, and concludes: “Ultimately, Elegy for April is a novel that transcends any limitation of genre or categorisation, stands supremely confident in its achievement and, to this reader at least, reveals itself as good enough to take its place with anything John Banville has ever written.”’ (The Irish Times, 16 Oct. 2010, Weekend, p.10.)

The Lemur (2008) John Glass, an Irishman in New York who is married to the daughter of Big Bill Muholland, a successful businessman in the cable business and former CIA agent, is required to undertake the biography of his father-in-law. He recruits a young researcher called Dylan Reilly [var. Riley], whom he nicknames “The Lemur”, and who is subsequently murdered - but not before he rings Glass with news of a secret which he claims entitles him to half the fee that Mulholland is paying Glass. Glass fears that Riley has turned up the secret of his own affair with the painter Alison O’Keeffe. In reality he’s discovered the secret of the Mulholland family which puts Glass’s pecadillo in the shade. Meanwhile, Captain Ambrose of the NYPD has identified Glass as the last man Riley rang before he was shot. (See COPAC > Kirkus Review - online; accessed 30.07.2011.)

Juggery-pokery: There is another version of von Kleist’s De Zerbrochen Krug trans. by Blake Morrison as The Cracked Pot played at Skipton Auction Mart using copious amounts of recorded Yorkshire dialect of 1911 (see Times Literary Supplement, 22 March 1996, p.20.)

What the Dickens!: In Birchwood (1973) Banville introduces a travelling circus, much as Dickens does in Hard Times while the term “whelp” is shared by both texts. If intentional, the borrowed trope and term are among very many intertextual elements in the novel including an echo of Joyce’s Dubliners in the naming of the protagonists Gabriel and Michael. (Note on Dickens and Joyce provided by Ryan Horner, UG Essay, UUC 2003.)

[ top ]

Aosdána (1): Anthony Cronin, “John Banville and Aosdana”, letter to The Irish Times (20 Dec. 2001), argues that Banville is mistaken about ‘the nature and purposes of Aosdána’ in supposing that it is for the support of ‘what he calls “hungry” people’. Cronin goes on to express surprise at his [Banville’s] ‘crusading zeal’, arguing that the most members of Aosdána [do not] ‘enjoy, like him, a degree of financial success [and enjoins him to] understand that membership is also an expression of identity of interest with others who have made the same difficult and often dangerous vocational choice as they have themselves but may not have the same good fortune.’

Aosdána (2): John Banville, letter to The Irish Times (10 Jan. 2002), answers Cronin’s letter on his ‘crusading zeal’. Banville explains: ‘The reason for my resignation was simple. I had for some years taken no active part in the proceedings of Aosdána, not because I disapproved of those proceedings, but because I was busy elsewhere, frequently out of the country, &c. It seemed, therefore, that the right and mannerly thing to do would be to resign.’ He also speaks of his proposal that emeritus status be created to facilitate new entrants and makes it clear that he has not received the cnuas since the mid-1980s.

Alan Gilsenan, dir., stage-version of Banville’s Book of Evidence as a dramatic monologue for the Royal Shakespeare Company [RSC], 2000.

QUB/English Society hosts reading and discussion by John Banville on 4 Dec. 2003 (Lanyon North, QUB, Belfast).

The play’s the thing: Fiach Mac Conghail, appt. Director of the Abbey Theatre in Feb. 2005, previously produced films for Paul Mercier, Marina Carr’s Ariel at the Abbey, and The Book of Evidence, a play about Malcolm Macarthur, with Kilkenny Arts Festival, as well as Dorothy & Tom Cross’s Medusa and The Silver Bridge by Jaki Irvine. (Irish Times, 2 Feb. 2005.)

“A Novel Choice” [Irish Times /James Joyce Centre lect. series]: John Banville selects Ulysses by James Joyce [‘First, and obviously, Ulysses, even though it may not be exactly what Tolstoy or George Eliot would have recognised as a proper novel’]; Molloy by Samuel Beckett [‘Molloy is Samuel Beckett’s prose masterpiece - although if the list were longer I would want to include Ill Seen Ill Said, a masterpiece of his old age’]; The Last September by Elizabeth Bowen [‘Elizabeth Bowen wrote The Last September when she was still in her 20s, but it is her finest achievement - and, incidentally, her own favourite among her novels’]. (See The Irish Times, 27 Sept. 2003, announcing a lecture series based on the 10 most voted for novels on a list provided by the commissioned lecturers to be hosted by the James Joyce Centre, 23 Oct. - 27 Nov. 2003.)

Malcolm Macarthur [often err. MacArthur; occas. McArthur] (1): b. 17 April 1945 [var. 1946]; arrested 4 Aug. 1982 and convicted of murdering Bridie Gargan - though not tried for the killing of Co. Offaly farmer Donal [var. Noel] Dunne, widely assumed to be his doing also - was sentenced to a life term of imprisonment and served as the model for the character Freddie Montgomery in The Book of Evidence . He was moved from Mountjoy to an Shelton Abbey, an open prison, on 6 May 2003 [with a view to assessing his suitability for early release]. In January 2005 Macarthur challenged his further detention as one of the the longest held prisoner in the state, and sought a High Court declaration that it is in contravention of the the Constitution and the European Human Rights Convention on the basis that a minister cannot perform a judicial function in over-riding the recommendation of the parole board, as well as damages from the Irish State. (see The Irish Times, 27 Jan 2005.)

Malcolm Macarthur - (2): Note that Macarthur’s son, a PhD student at TCD in 2005, was offered as an example of journalists’ intrusions of privacy in an Irish Times article by Fintan O’Toole (“Private lives, public eyes”, 5 Feb. 2005).

[ top ]

Malcolm Macarthur - (3): A full account of events leading up to and following on Macarthur’s murder of Bridie Gargan, a nurse who was sun-batheing in the Phoenix Park when he crossed her path, is given in an Irish Times article by Conor Lally of 18 June 2011 [online - and conserved at the Irish Free Press website [online - accessed 20.07.2011]. The article relates his killing of Gargan with a lump hammer and Donal Dunne with a shotgun in Co. Offaly days later, before hiding up in Pilot View, Dalkey - the home of Peter Connolly, then chief govt. legal adviser [Attorney General] - giving rise to Conor Cruise O’Brien’s coinage “gubu” to reflect the Taoiseach Charles Haughey’s explanatory phrase, “grotesque, unprecedented, bizarre and unbelievable”. It concludes by reflectig on the unlikelihood of Macarthur’s being released from prison ‘any time soon’.

Malcolm Macarthur (4): The Sunday Independent (1 Sept 2002) carried a banner, “Was Macarthur [sic] about to reveal child sex ring? - Garda believe killer had ‘sensational’ information.” See also earlier article by Ralph Riegel in the Irish Independent (26 April 2002), covering allegations made by Phil Hogan (Fine Gael TD for Carlow/Kilkenny) that McArthur [sic] is a paedophile associated with another paedophile in a position of authority in the SE Health Board and that he had sex with an unnamed inmate of an Irish care facility in the bailiwick of the Ministry of Education. The relevant article from the Independent is conserved on the Free Speech website [online] - a website edited by Jim Cairns, author of a work on ‘disappeared’ young persons. The site page referring to Macarthur is titled “SRA Missing Persons and Satanism” and reflects an obsession with the idea of a ‘Jesuit-Vatican’ plot to rule the world. The report concerning Macarthur reports actual exchanges in Dail Eireann involving Michael Woods, Minister of Education (Fianna Fáil) in which the latter undertakes to investigate the allegations.

Malcolm Macarthur (5): As the District judge before whom Malcolm Macarthur was arraigned, Mary Kotsonouris [...] provides a disturbing personal observation on the Macarthur case, writing: ‘There was no way that anyone standing as far away as the road could see him in the gap, but through the barred windows, I heard a sound that was neither human nor animal, a low but thunderous swelling of noise that was as inchoate as it was meaningless. It is a sound I hope never to hear again – the baying of the crowd. Five minutes later, [Macarthur] was charged with two murders.’ In her book she refers to “McArthur”; the rather than Macarthur - an error pointed out by the reviewer. (See John McBratney, review of Kotsonouris, “ ‘tis All Lies, Your Worship”, Tales from the District Court, in Irish Times, 23 July 2011, Weekend, p.11.)

“Beckett’s Last Words”: Banville delivered a public lecture with this title in Theatre P, Newman [Arts] Building, Belfield, on on 20 Feb. 2008, at 7pm.

Valuations of Banville’s first book in the first edition: Long Lankin (Martin Secker & Warburg 1970): Peter Ellis (London) - £450; Simon Finch Rare Books (London, UK) - US$1562.62; Hemingway’s Books (Sumas, WA, USA.) - US$800 [all in 2004].