Life

| 1856-1917; b. 17 Oct., Clontarf, Co. Dublin; eldest dg. and second of seven children of Rev. James William Barlow [q.v.] and his cousin Mary Louisa Barlow (1832-94); educated at home; well-read in French and German and travelled widely in Europe, and visited Greece and Turkey in her twenties; lived most of her life in “The Cottage”, a substantial thatched house in Raheny, Co. Dublin [now an OP home]; wrote ballads and tales of peasant life in the west of Ireland, chiefly about Lisconnel and Ballyhoy [now Dollymount]; first published fiction in Dublin University Review [TCD], ed. by T. W. Rolleston [q.v.] who compared her with William Carleton; her poetry collections include Bog-land Studies (1892); The End of Elfintown (1894) - a fairy-tale extravaganza; Ghost-Bereft (1901), a narrative poem; The Mockers and Other Verses (1908); Doings and Dealings (1913); Between Doubting and Daring (1916) - reputedly admired by Swinburne; issued Irish Idylls (1892), being short-story sketches in which Lisconnel is said to stand ‘in the common light of day, a hard fact with no fantastic myths to embellish or disprove it’ and ran into 9 editions; |

| a second series appeared as Strangers at Lisconnel (1895), to be followed by Maureen’s Fairing and Other Stories (1895); Mrs Martin’s Company and Other Stories (1896); A Creel of Irish Stories (1897); From the East unto the West (1898); From the Land of the Shamrock (1900); By Beach and Bog Land (1905); Irish Neighbours (1907), and Irish Ways (1909); her novels in the same vein were Kerrigan’s Quality (1894) and The Founding of Fortunes (1902), the tale of an impoverished youth from a bog-cabin home who gets rich by devious means; became an associate-member of the English Society for Psychical Research, April 1895; her father joined in 1901 and helped establish a Dublin Section in 1908 (ceasing to exist in 1915); Jane joined with Lady Gregory, Hyde, “AE” [George Russell], W. B. Yeats, and others in ‘An Appeal from Irish Authors’ (Freeman’s Journal, 13 Dec. 1904; in The Irish Times, 5 Jan. 1905), protesting the Dublin Corporation’s decision about the Hugh Lane Gallery; |

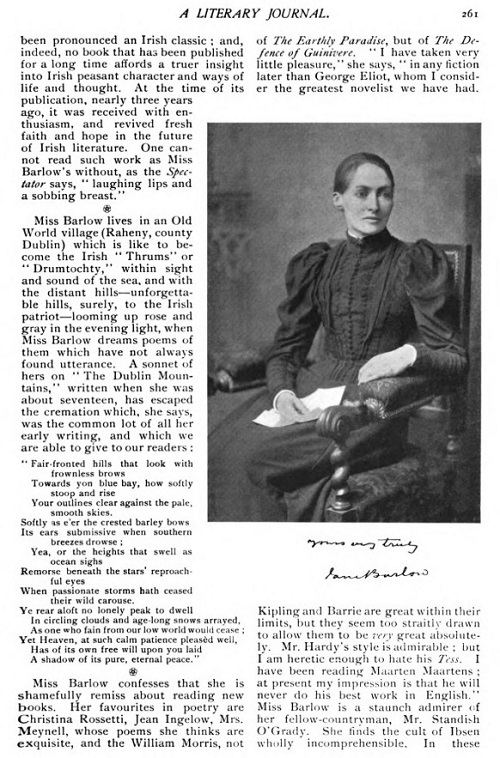

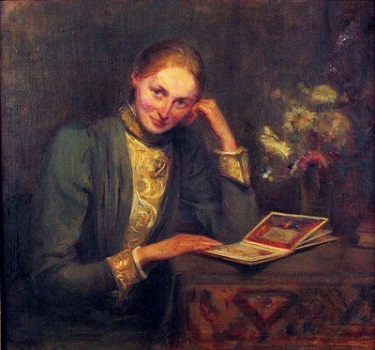

| received D.Litt from TCD - the first woman to do so - and contrib. to National Literary Society; elected vice-pres. of the Society in 1897; much read in England and America but was increasingly scorned by the literary revivalists in Ireland for her supposedly ‘stage-Irish’ portraits of the people; both George Birmingham and Yeats (only writes about ‘old women and hens’) excluded her from story-collections; suffered from depression in later life; d. 17 April, at St Valerie [a substantial early Victorian house], on the Dargle nr Bray - where she moved with her siblings after their father’s death in 1913 (‘after her father’s death she just stopped living’, acc. to Katherine Tynan); Barlow was a correspondent of Alfred Russel Wallace, the evolutionary scientist [see note]; an obituary appeared in The Irish Times (18 April 1917); a sister Katharine also became a member of English Society for Pyschical Research in 1918, while James Arthur (d.1932) did likewise in 1929; there is a portrait by Sarah Purser and a photo-port. in was printed in The Monthly (March 1897). ODNB JMC CAB DIW DIB DIL KUN DIH SUTH FDA OCIL [RIA DIB] |

|

|

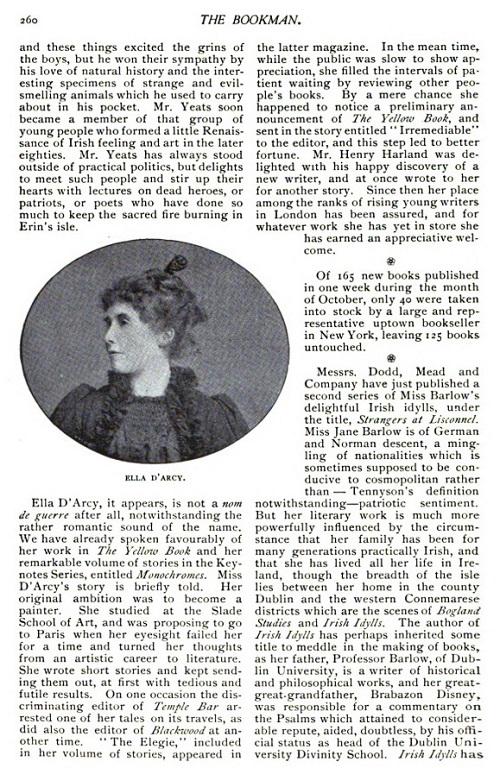

| Port. by Sarah Purser (1894) | Unattrib. port - Wikipedia] |

[ Click each portrait for larger images in separate windows. ]

[ top ]

Works| Poetry | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Short fiction | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Novels | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Anthologised (sel.) | |||

|

|||

| Discography | |||

|

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

|

Irish Idylls (London 1892; NY 1894) |

Doings & Dealings (1913) | |

[ top ]

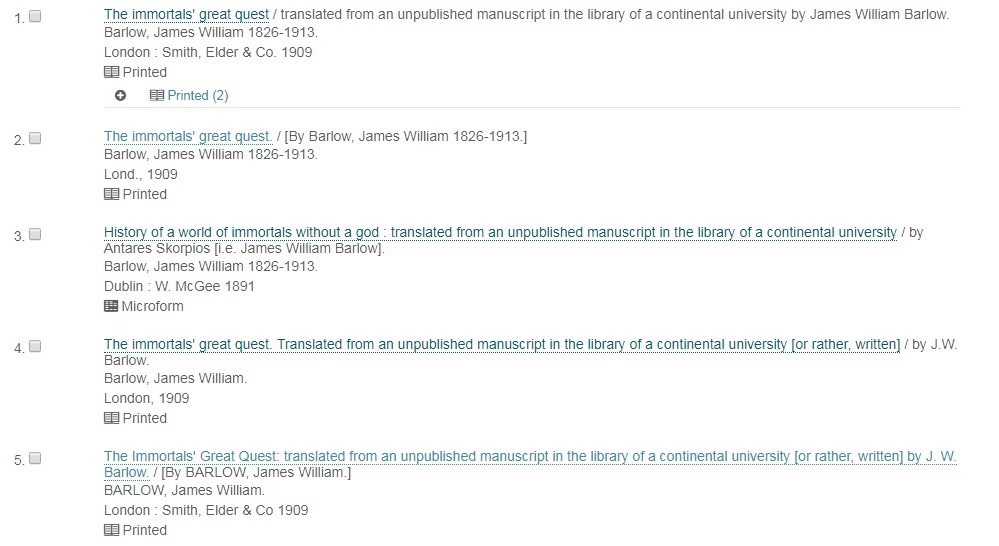

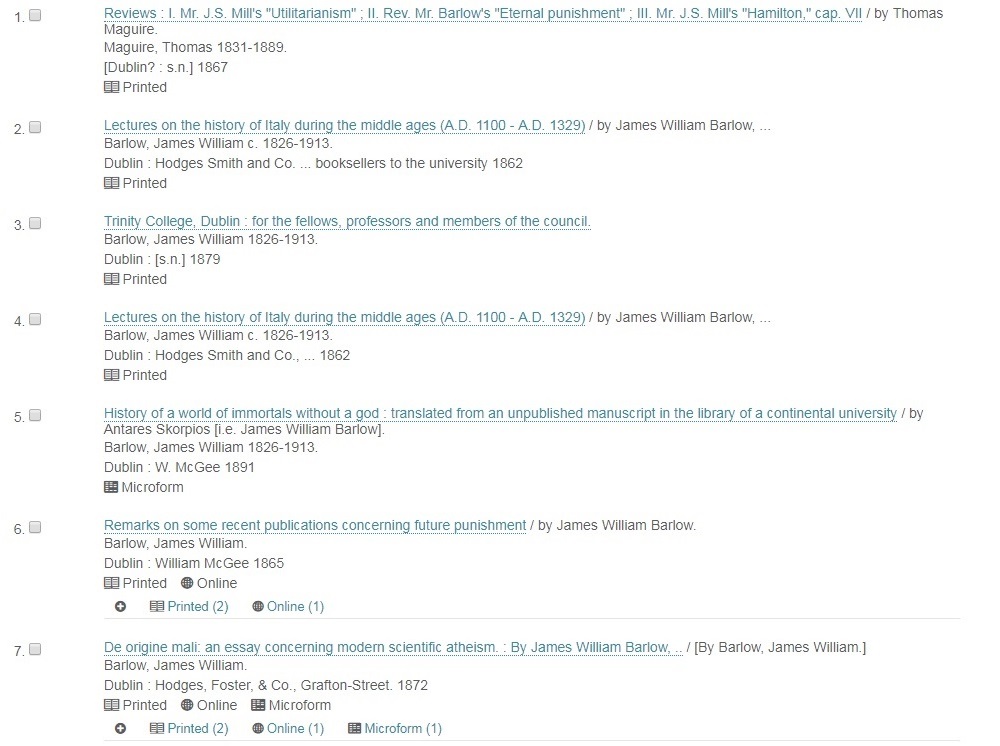

| Worldcat lists: |

|

| —See Worldcat online; accessed 31.10.2011. |

[ Note: A work entitled The Peacock, the Baboon, and the Money-Spinners which is ascribed to Thomas Moore and pronounced to be ‘a newly discovered, unedited poem’ on its title page has been found in the Biblioteca National del Patrimonio Ibero-americano (Mexico City). [See extracts as attached. ]

[ top ]

Criticism| Older notices |

|

|

| Recent notices |

|

|

[ See also the entry in Wikipedia. ]

[ top ]

|

|

[ top ]

W. P. Ryan, The Irish Literary Revival: Its History, Pioneers and Possibilities (London: Paternoster Steam Press 1894), remarks: ‘Jane Barlow’s Irish Idylls are a luminous index to young Irish authors of that world of appealing humanity which is still to be found by observant eyes in Irish local life ... When Rolleston was editing the Dublin University Review her first poem came to him anonymously. He was at once struck with its power, but the “brogue” did not wholly pass muster. Several such pieces were afterwards given to the world in Bogland Studies (1892). Irish writers whose early attempts are scorned of some critics may take courage from the example and fate of this first offering. United Ireland welcomed it, and saw its promise; but several critics could make nothing of it. They shrugged their shoulders over the ‘brogue’ and the whole form, confessed their inability to read it, and cast it away. Afterwards when Irish Idylls made a stir, and the ‘studies’ were brought up again on the strength of it they found less frosty audience. Miss Barlow now finds herself amongst our foremost writers, with every encouragement to go on and prosper. She lives at Raheny, Co. Dublin, where her father (a TCD man) is vicar. (Ryan, p.146). [Incl. note to the effect that Barlow disparages the brogue in Irish literature as unnatural in her Preface to Lisconell [sic] and is praised by others for avoiding it.]

W. J. Paul, Modern Irish Poetry (Belfast Steam Printing Co. Ltd. 1897), Vol. II, contains a biographical sketch in which her home in Raheny is described as ‘a cottage with a thatched roof and quaint little windows peeping out amnong the climbing roses that cover it. Its antiquity is attested by its mud walls - a genuine bit of Irish architecture.’ Further: ‘Miss Barlow herself is a slender young woman, with somewhat of humility and shyness in her manner. For society she has no inclination; hers is one of those natures that strikes its deepest roots at home’. Paul relates that she sent “Walled Out; or, Eschatology in a Bog” to the Dublin University Magazine, and that the editor was obliged to advertise for the author. Paul remarks, ‘No one, since Carleton, has depicted the Irish peasant with his manysided character, so natural and so real as she. It is surprising how attractive and fascinating this homely and unpretentious class of Irishman becomes when described by the hand of genius. He rises before us and relates the story of his joys and sorrows. As he does so, one can almost fancy they hear the tone of his voice. She is full of sympathy for her subject. She writes of Ireland animated by a desire to show the actual life of the people in its mingled humour and pathos. That she has done so with success every reader of her character-sketches, with any knowledge of the subject, will readily admit.’ (p.108).

W. B. Yeats: Yeats wrote: ‘... I have regretfully excluded Miss Barlow’s Irish Idylls because, despite her genius for recording the externals of Irish peasant life, I do not feel that she has got deep into the heart of things.’ (Commentary on his list of thirty Irish best books, in Dublin Daily Express, 27 Feb. 1895; Letters, ed., Wade, pp.246-51; p.248; see further under Emily Lawless and W. B. Yeats). George Birmingham also excluded Barlow’s Irish Idylls from a collection he edited.

| Hannah Lynch [q.v.], lecturing on Irish writers in Paris, 1896, singled out Emily Lawless’s novels Grania and Hurrish, and Jane Barlow’s Irish Idylls. These, she informed her audience, were “undoubtedly the best stories the young school of Irish Celts has produced”. (See Faith Binckes and Kathryn Laing on Lynch in The Irish Times, 26 July 2019 - online. |

J. M. Synge “The Old and New in Ireland”, in The Academy and Literature (6 Sept. 1902), rep. Collected Works, ed. Alan Price (London: OUP, 1966), [Vol. II: Prose], pp.383-86: ‘Ten years ago, in the summer of 1892, an article on Literary Dublin, by Miss Barlow, author of Bogland Studies and some other charming work, appeared in a leading English weekly. After dealing with Professor Mahaffy, some other Irish writers, and the periodicals of Dublin, she summed up in these words: “This bird’s eye view has revealed no brilliant prospect, and the causes of dimness considered, it is difficult to point out any quarter of the horizon as a probable source of rising light.” / No one who knows Ireland and Irish life will be likely to charge Miss Barlow with lack of insight, although when she wrote the literary movement which is now so apparent was beginning everywhere through the country’ (p.383).

A literary assassination ... ?| Ernest A. Boyd, Ireland’s Literary Revival (Dublin: Maunsel & Co. MCMXVI [1916; NY: Alfred A. Knopf 1922), pp.209-11. |

|

Dominic Daly, The Young Douglas Hyde: The Dawn Of The Irish Revolution And Renaissance, 1874-1893 (Dublin: Irish University Press 1974), cites Hyde’s diary entry of 8 Feb. 1893, in which Hyde meets Jane Barlow, the self-effacing ‘incognita’ and friend of Sarah Purser. (p.160.) In a footnote, Daly quotes W. B. Yeats’s account of Barlow in The Bookman (Aug. 1895): ‘She is master over the circumstances of peasant life, and has observed with a delightful care no Irish writer has equalled, the coming and going of hens and chickens on the doorstep, the gossiping of old women over their tea, the hiding of children under the shadows of the thorn trees, the broken and decaying thatch of the cabins, and the great brown stretches of bogland; but seems to know nothing of the exultant and passionate life Carleton celebrated, or to shrink from its roughness and its tumult’ (Daly, op. cit., p.221).

Stephen Brown, S.J., Ireland in Fiction (Maunsel 1919) - Remarks on Flaws (1912): exceptionally involved plot; four whole new sets of characters; minute observtion [..] of character; picturesque conversations; .. caste [of] spiteful, petty, small-minded and generally disagreeable personag, es. The are nearly all drawn from the middle and pper classes in the South of Ireland, Protestant and Anglicised. The snobbishmess, petty jealousies, selfishness of some of these people is set forth in a vein of satire. The incidents include an unusually tragic suicide. (Stephen Brown, S. J., Ireland in Fiction (1919). pp.21-22. For sundry remarks on her stories and novels See Brown - as attached.)

[ top ]

Benedict Kiely, Poor Scholar: A Study Of The Works And Days Of William Carleton, 1794-1869 (London: Sheed & Ward 1947; rep. Dublin: Talbot Press, 1972): ‘The black shadow spreads out over the century and over the writers of the century. Jane Barlow who, according to T. W. Rolleston, closely resembled Carleton, and who, as far as Irish fiction was concerned, helped at the deathbed of the nineteenth century, found for her imagination and her art a small village of poor people in a western bog. The bogland around Lisconnel was lonely, but it was, in a sombre fashion, colourful. “Heath, rushes, furze, ling, and the like have woven it thickly, their various tints merging, for the most part, into one uniform brown, with a few rusty streaks in it, as if the weather-beaten fell of some huge primaeval beast were stretched smoothly over the flat plain. Here and there, however, the monochrome will be broken: a white gleam comes from a tract where the breeze is deftly unfurling the silky bog-cotton tufts on a thousand elfin distaffs; or a rich glow, crimson and dusky purple dashed with gold, betokens the profuse mingling of furze and heather blooms; or a sunbeam, glinting across some little grassy esker, strikes out a strangely jewel-like flash of transparent green.”’ [Cont.]

Benedict Kiely, Poor Scholar [...] (rep. edn. 1972): ‘Jane Barlow called that book of stories about Lisconnel by the name Irish Idylls (Hodder & Stoughton, 1892) and Ireland is one of those odd countries in which it is almost always possible to uncover something of the idyllic. But even in Jane Barlow’s coloured land the bog could turn grey and stiffen with frost, the cut wind could blow blighting, corrupting blackness into the seed-potatoes on which life in Lisconnel depended. Faces could lengthen and heads shake, superurtious minds draw omens from the flickering white flights of sea-grills over the bog, from the gloomy croaking and flapping of passing herons, from “the long trains of wild duck, scudding by like trails of smoke.” A man, distraught with famine-fever, could bolt himself and his children into the cabin while the woman of the house went searching for food; and when she returned her husband was too weak to answer her battering at the door. In the morning he and his children were dead in the cabin, the mother dead outside on the ground, and in Lisconnel they said her tormented spirit battered night after night on the closed and bolted door. (Irish Idylls, n.p.; Kiely, op. cit., p.136.)

Patricia Boylan, All Cultivated People: A History of The United Arts Club, Dublin (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1988), makes reference to her support for the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery in 1905 (p.7). Also notes that she was published by Rolleston as editor of Dublin University Review (p.10), and quotes Winifred Letts’s sketch of her: ‘I see Jane Barlow, in a wind-blown cloak; a spirit just made tangible in slender form and pale colouring, austere, shy, delicately strong; an exquisite poet ...’ [from Knockmaroon] (pp.108-09). [Note: it was at a party given by Winifred Letts that Jane Barlow broke off her friendship with Katharine Tynan; information given by Anne van Weerden (Utrecht).]

J. W. Foster, Irish Novels 1890-1940: New Bearings in Culture and Fiction (Oxford UP 2008): ‘One can see a tentative departure in this direct [i.e., a newly inaugurated Irish fiction that avoids the revival’s project of ‘recovery of the Irish peasants as real human beings’] in Irish Idylls (1892) by Jane Barlow, daughter of a Reverend Vice-Provosts of Trinity [2] College Dublin. This was a very popular set of stories in which the Connemara peasant is portrayed respectfully and fairly knowledgeably (the speech pattersn and idioms are there, even if rather unlocalised), though the note of condescension is impossible to miss, likewise the feeling that the Victorian eloquence of the storyteller is itself civilising, as it were, her quaint subjects, despite a textural density of prose that confers its own respect on its subjects.’ (pp.2-3.) [Cont.]

J. W. Foster (Irish Novels 1890-1940, 2008) - cont. ‘Rehearsal did not deepen her fiction into a pervasive sense of social malaise of some remediable kind. IN the opening sketch of Irish Ways (1909), Barlow identified three popular Irelands she was eschewing: pitiable Ireland, sentimental Ireland, and glamorously Celtic Ireland. She offered instead a fourth Ireland, what we might call uniquely ineffable Ireland, its “atmosphere, elusive, impalpable, with the property of lending aspects bewilderingly various to the same things seen from different points of view” (Irish Ways, 1911 Edn., p.3.), an Ireland essentially beyond the range of real reform, even if desirable.’ In Irish Ways only one practical step might be taken toward alleviate the penury of the west of Ireland: mobile lending libraries, around which she builds one story, “An Unseen Romance”. Barlow turned - I almost said “reverted” - to what she knew thoroughly, life in the country house, in such a novel as Flaws (1911).’

Obiter dicta: Foster speaks of the ‘all too realistic minor gentry’ in this ‘dull and interminable novel’ which proves that ‘Barlow was at home solely at the precise distance from her characters she maintained in her peasant stories.’ (p.3.)

| James E. Carson on Barlow’s Irish Idylls & Strangers at Lisconnel (Librivox 2013) |

Remarks are quoted in the publisher’s note to Irish Idylls (1892) [quoted]: ‘So, by hook or by crook, Lisconnel holds together from year to year, with no particular prospect of changes; though it would be safe enough to prophesy that should any occur, they will tend towards the falling in of derelict roofs, and the growth of weeds round deserted hearthstones and crumbling walls.’ Carson writes: ‘Although of high social standing, I suspect she might have been a “left-footer” but maybe not, her sympathies lying so dramatically with local Irish peasants of her acquaintance. She portrays a decided antipathy toward English rule/subjection of these peasants along with a rather stark anti-clerical and anti-religious leaning, which I find somewhat unusual for the time.’

|

Jack Fennell, ‘10 Irish Fiction Authors’, in The Guardian (19 Dec. 2018) - on Jane Barlow: ‘Sometimes under her own name, and sometimes as “Felix Ryark,” Barlow wrote across a variety of genres, from Oriental fantasies to quaint tales of Irish country life, but her sci-fi always has an uncomfortable existential edge: the novel History of a World of Immortals Without a God - has a misanthropist from Earth plunging the immortal inhabitants of Venus into never-ending despair, while her short story “An Advance Sheet” marries predestination and a Nietzschean “eternal return” to create a horrifying universe without variety or freedom.’ (Fennell, ‘James William Barlow (1826-1913)’, in The Green Book: Writings on Irish Gothic, Supernatural and Fantastic Literature, 18 [Swan River Press] (Samhain 2021), pp.29-36 [available at JSTOR - online; accessed 15.11.2021. Note: Fennell cites the Internet Archive copy of the novel; see also under James William Barlow [q.v. - as supra].)

| Jack Fennell, ‘10 Irish Fiction Authors’, in The Guardian (19 Dec. 2018). |

|

| -Available online; accessed 23.06.2019; see further infra. |

[ top ]

| Extracts from texts by Jane Barlow | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| [ Note: Full text versions of many of Barlow’s works are available in Internet Archive - as supra. |

[ top ]

References

Anthologies: Daniel Karlin, ed., The Penguin Book of Victorian Verse (London: Penguin 1997), incls. Jane Barlow - with 8 other Irish poets: William Allingham, Edward Dowden, William Larminie, James Clarence Mangan, George William Russell [AE], John Todhunter, Oscar Wilde, W. B. Yeats ... amidst tens of English poets.

| See Stephen Brown, S. J., Ireland in Fiction (1919) - remarks on her stories and novels, as attached; also his remarks on Flaws (1912) - as supra and Bio-dates - as infra. |

Belfast Public Library holds 15 titles including Mrs Martin’s Company; The Mockers and Other Verses; Maureen’s Fairing; Irish Ways; Irish Idylls; Doings and Dealings; Kerrigan’s Quality; Mac’s Adventures; The Ghost Bereft; The Founding of Fortunes; A Creel of Irish Stories; From the East to the West.

[ See also the Wikipedia entry on Jane Barlow - online; accessed 09.02.2018. ]

Dictionary of Irish Biography (RIA 2009; rev. entry Oct. 2021) “Jane Barlow”, by Frances Clarke [...]

Despite her family’s unionist background, she considered herself a nationalist from childhood. Inspired by the Young Ireland and Fenian movements, she contributed romantic nationalist verse to the United Irishman of Arthur Griffith, though this was published anonymously, to avoid embarrassing her father. Similarly influenced by the Gaelic revival, she attempted to learn Irish and in 1900 was elected as an honorary member of the St Columba branch of the Gaelic League. Her lengthy correspondence with Katherine Tynan and Sarah Purser (who painted her portrait in 1894) testifies to these influences, and she often signed herself Sinéad. However, she later became alienated by the radical turn of Irish nationalism, and responded critically to the 1916 rising in verse.

[...]

Her poetry was included in many contemporary anthologies of Irish writing, but interest in her work was not sustained, and her characterisations of the native Irish subsequently appeared stereotyped.Dictionary of Irish Biography (RIA 2009; rev. 2021) - available online; accessed 27.03.2022.

[ top ]

Notes

Hugh Lane Gallery (1): Barlow joined with S. H. Butcher, Augusta Gregory, Douglas Hyde, Somerville & Ross, Emily Lawless, George Russell, and W. B. Yeats in ‘An Appeal from Irish Authors’ (Freeman’s Journal, 13 Dec. 1904), protesting against the corporation judgement on Hugh Lane’s [Municipal] gallery.’ (See Adrian Frazier, ‘Paris, Dublin: Looking at George Moore Looking at Manet’, in New Hibernia Review, 1, 1, Spring 1997, pp.19-30.)

Hugh Lane Gallery (2): See Alan Denson, Letters from AE (London: Abelard-Schuman 1961), p.54, giving details of the same letter in the papers of George Russell (Dec. 1904), printed in The Irish Times (5 Jan. 1905), appealing for donations to the value of £30,000 or £40,000 to purchase a collection of paintings ‘chosen by experts from the Staats-Froves and Durand-ruel Collections, and admitted to be the finest representation of modern French art outside Paris’, currently showing at the Royal Hibernian Academy; signed by Barlow, with Gregory, Butcher, Hyde, Somerville, Martin Ross, Lawless, Yeats and Russell (“AE”).

Bio-dates: Anne van Weerden (Utrecht Univ., NL) notes that the Church of Ireland attests to Jane Barlow’s birth-date in 1856 (formerly 1857 on this website) and has emended the Wikipedia entry to that effect.

Felix Ryark [pseud.]: Anne van Weerden remarks that A History of the World of Immortals Without God (1891), a sci-fi novel set on the planet Venus ascribed to Felix Ryard [pseud.] on the t.p. was written by her father - in spite of frequent erroneous attributions to her and suggests that A Strange Land (1908) was by him also. (Email correspondence, Dec. 2017-Feb. 2018.) She also mentions that Jack Fennell derives “Felix Ryark” from the Irish radhairc “a view” prefixed by felix, Latin for “happy”. [See bibliographical details - supra.]

| Additional notes: |

1] Anne van Weerden writes to RICORSO that Mac is a character in “The Field of the Frightful Beasts”, a story in From the East to the West (1898) and that The Battle of the Frogs and Mice was translated [viz., ‘rendered into English’] by Jane Barlow. (The online links above have also been supplied by Anne van Weerden.) |

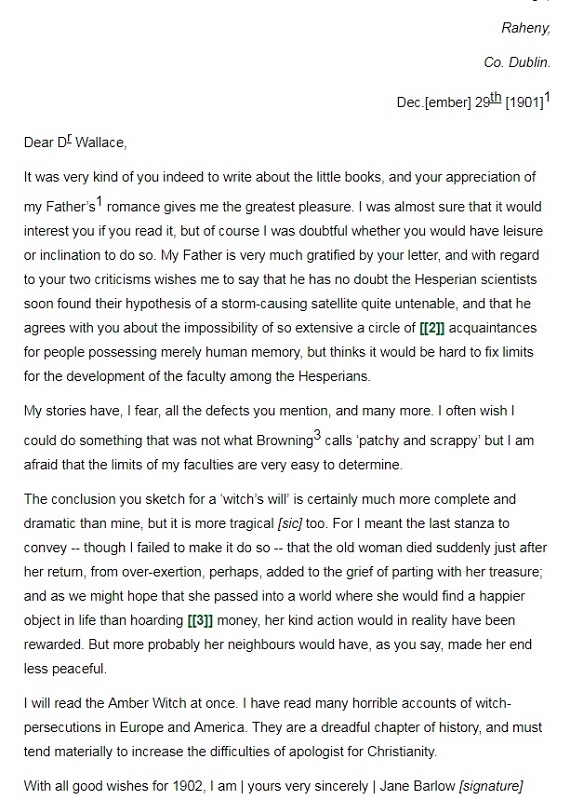

2] Van Weerden also cites a letter of Jane Barlow to Alfred Russel Wallace, now held in the British Natural History) Museum, which definitely confirms that A History of Immortals Without God is by Barlow Snr and not by Jane Barlow. See infra. |

|

[ top ]

Research notice: Jane Barlow died in October 1917; her siblings William Ruxton Barlow in 1922, Maurice Barlow in 1923, and Katharine Barlow in 1929. No date has been found for John’s Barlow’s death but in March 1930 he was mentioned as copyright holder of some of his sister’s books and he may have died soon thereafter. Jane Barlow had become an associated of the English Society for Psychical Research in 1895. Her father had become a member in 1901, and in 1908 he had helped to establish the Dublin Section. In January 1918, only some months after Jane’s death, Katharine also became a member of English Society, the Dublin section having ceased to exist before 1915. [...]. (See Researchgate - online; link supplied by Anne van Weerden.)

[ top ]

|

||

|

||

| —Available at HathiTrust - online; accessed 22.10.2018. |

[ top ]

A Strange Land (2908): The novel, whose authorship is disputed between Jane Barlow and her father Rev. James Barlow, was received in an Australian newspaper in The Advertiser [Adelaide] Sat., 6 June 1908):

|

||

| —Trove (National Library of Australia) - online; accessed 24.03.2019; noticed by Anne van Weerden. See bibliographical remarks, supra. |

[ top ]

| COPAC listings for A History of a World of Immortals Without God (1891; rep. 1908) by Rev. James William Barlow |

|

| Note: Holding libraries omitted from this copy can be viewed by double-clicking the page images; |

| James William Barlow - Full list (COPAC): |

|

| Note: Holding libraries omitted from this copy can be viewed by double-clicking the page images; for active links, go to COPAC - online; accessed 25.06.2019]. |

Alfred Russel Wallace - Jane Barlow’s correspondence with Wallace is available in transcriptions at the Natural History Museum website (UK). A search of the collection made by Anne van Weerden returned the following list of seven letters: 11 Feb. 1895*, 29 Dec. 1901*, 14 July 1904, 15 Sept. 1912, 23 Oct. 1913*, 13 Feb. 1913*, 12 March 1913 [addressed to Annie Wallace [née Midden]. Those marked * are available as transcriptions online. On 23 Oct. 1913 she wrote: ‘My beloved Father passed away in July, and I am so lonely without him that were it not for the hope of reunion beyond this world, I should quite despair.’ (See transcript.)

Note: Wallace has been identified as the the founder of the Society of Psychical Research but was primarily known as the discoverer of Evolutionary theory independently of and similtaneously with Darwin - i.e., evolution through natural selection. In the Dictionary of Irish Biography (2009; rev. entry 2021) he is erroneously identified as the founder of the Irish branch of the Psychical Research Society.

| Letter from Jane Barlow to Alfred Russel Wallace of 29 Dec. 1901 |

`` `` |

| Source: Wallace Letters at the Natural History Museum - transcript [search conducted by Anne van Weerden; notified to Ricorso 15.11.2021]. |

The Immortals’ Great Quest (1909) - An immortal race of inhabitants on “Hesperos” (Venus) live cyclical lives: they grow old, grow young, then grow old again - with no reproduction, and no disease or death from natural causes. The planet’s hundred million inhabitants arrived all at once on the planet from somewhere else; if an individual’s suffering reaches a certain level he simply vanishes and reappears at the planet’s temperate South Pole; the northern and southern hemispheres of the planet are separated by a permanent wide belt of hurricane at the equator, impassable except by submarine. World Cat. Synopsis - online; accessed 19.11.2021.)

Namesake: West Coast Rare Books [James Street, Westport, Co. Mayo] lists Stephen Barlow, The History of Ireland. From the Earliest Period to the Present Time; embracing also A Statistical and Geographical Account of that Kingdom; forming together a Complete View of its Past and Present State, under its Political, Civil, Literary, and Commercial Relations. First Edition. Two Volumes. London, Printed for Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, 1814. 20.5 x 12.5 cm. Vol.1: xvi, 476 pages. / Vol.2: xii, 524 pages. Complete with all Illustrations incl. a folding map of Ireland and a folding view of Dublin. One plate bound in wrong position (Vol.1 vs. Vol.2) New (2019) green cloth with gilt title on spine. New end papers. Original marbled edges. Very good condition. 2019 Bindings by Kenny’s Bindery, Galway. Internally slightly age darkened / browned. Edges dust dulled. Minor wear to some pages, not affecting text. A very nice set; rebound in 2019. (See West Coast Rare Books Cat. - onlline & this title; [Vol. 2 also available with page-views in Google Books - online; accessed 19.11.2021.]

[ top ]