Notes on Sir Thomas Browne and Maria Edgeworth

as sources of epigraphs in The Secret Scripture (2008)

| Sir Thomas Browne | Maria Edgeworth |

| [ To view in separate window, click here. ] | |

| Census of Recurrent Words in The Secret Scripture - as attached. |

| The Engine of Owl-light (1987) | The Secret Scripture (2008) |

The Engine of Owl-light (1987): Barry chose as his epigraph a passage from Browne’s Urn Burial - viz., Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial, or a Brief Discourse of the Sepulchral Urns lately found in Norfolk (1658).

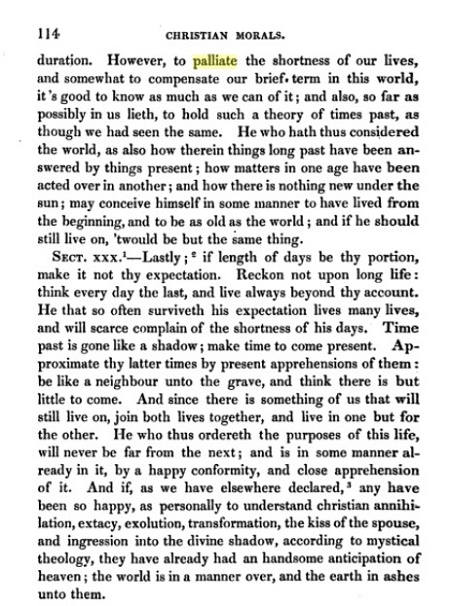

‘However, to palliate the shortness of our Lives, and somewhat to compensate our brief term in this World, it’s good to know as much as we can of it, and also so far as possibly in us lieth to hold a Theory of times past, as though we had seen the same. He who hath thus considered the World, as also how therein things long past have been answered by things present, how matters in one age have been acted, over in another, and how there is nothing new under the sun, may conceive himself in some manner to have lived from the beginning, and to be as old as the World; and if he should still live on, ‘twould be but the same thing.’ (Cf. ‘No new thing ... &c.’ is from Ecclesiastes the Preacher/OT.)

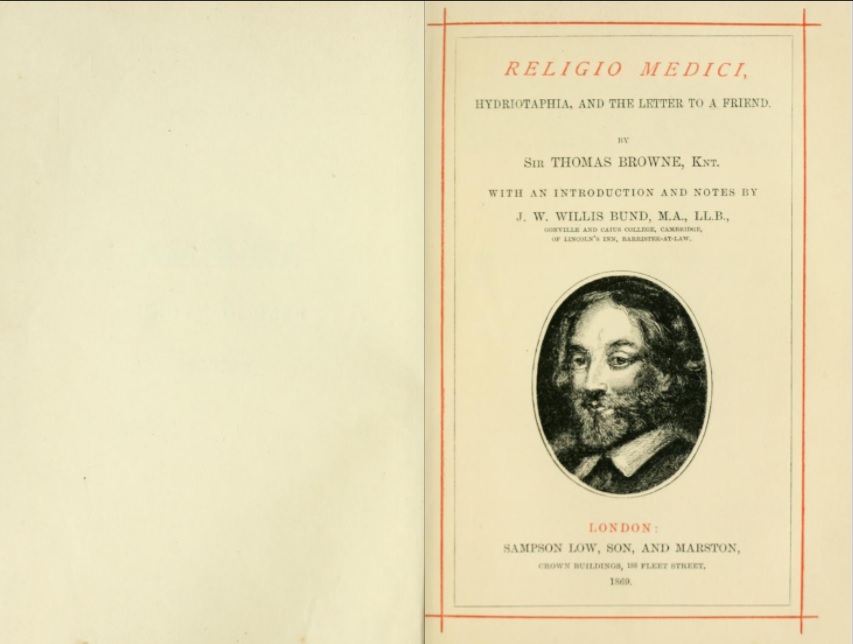

Note: Contrary to the attribution, the above epigraph is actually from ‘Christian Morals’ - first published in Posthum. Works, 1712 and reprinted with a commissioned preface by Dr. Johnson in the Dodsley Edn. of 1756], Pt. II, Sect. XXIX. A copy of that text is to be found in editions of Browne’s writings by Jeffreys (1825) and Wilkins (1835) but not in the edition of Religio Medici cited at some length in the text of The Sacred Scripture (2008) - as infra - where a volume of Religio Medici in that edition plays a significant part in the plot. Similarly, the epigraph from Browne on the front paper of The Sacred Scripture is likewise taken from Christian Morals - notwithstanding the fact that it is not included in the Sampson edition edited by Willis Bund in 1869 which is so copiously described there, and which can readily be identified with the title in the Colbeck Bibliography [infra]. And finally, Dr. Grene in the later novel quotes the from the epigraph to The Engine of Owl-light - ”to palliate the shortness of our lives” - and clearly attributes it to the Religio Medici where he purports to have read it while flicking through the opening pages. (The 1869 can be viewed at Internet Archive - online.)

Hence the ‘veritable gospel’ to which Roseanne refers in The Secret Scripture is not the only text by Browne within Barry’s grasp or possession, though the passage quoted by Dr Grene in that novel is indeed to be found at the opening of the 1869 edition Religio Medici edition so materially cited so materially there. One clue to the alternative source is the use of capital letters for substantives in the epigraph in The Engine of Owl-light since but same typographical rule has not been followed elsewhere - suggesting that it might have been introduced by Barry to confer an appearance of antiquity on the epigraph of that novel. The bibiographical question of sources - as distinct from the literary-textual one - cnnot be resolved without speaking with the author. [BS: 14.05.2017].

’Christian Morals’, in Sir Thomas Browne’s Works, ed. S. Wilkin (London 1825), Christian Morals, Pt. III [Part the Third]

[...]

Available at Google Books - online; accessed 24.05.2017.

“Christian Morals” [1712] , in Sir Thomas Browne’s Works Including His Life And Correspondence, ed. by Simon Wilkin F.L.S., Vol. IV (London: William Pickering; Norwich: Josiah Fletcher 1835) - Sects. xxviii-xxxx. Sect xxviii - That a greater number of angels remained in heaven, than fell from it, the school men will tell us; that the number of blessed souls will not come short of that vast number of fallen spirits, we have the favourable calculation of others. What age or century hath sent most souls unto heaven, he can tell who vouchsafeth that honour unto them. Though the number of the blessed must be complete before the world can pass away; yet since the world itself seems in the wane, and we have no such comfortable prognosticks of latter times; since a greater part of time is spun than is to come, and the blessed roll already much replenished; happy are those pieties, which solicitously look about, and hasten to make one of that already much filled and abbreviated list to come. (CM, Wilkins, 1835, Part III, p.13.) Sect. xxix - Think not the time short in this world, the world itself not being long. The created world is but a small parenthesis in eternity, and a short interposition, for a time, between such a state of duration as was before it and may be after it. And if we should allow of the old tradition that the world should last six thousand years, it could scarce have the name of old, since the first man lived near a sixth part thereof, and seven Methuselahs would exceed its whole [113] duration. However to palliate the shortness of our lives and somewhat to compensate our brief term in this world, it’s good to know as much as we can of it; and also so far as possibly in us lieth to hold such a theory of times past, as though we had seen the same. He who hath thus considered the world, as also how therein things long past have been answered by things present; how matters in one age have been acted over in another and how there is nothing new under the sun; may conceive himself in some manner to have lived from the beginning and to be as old as the world; and if he should still live on ‘twould be but the same thing. (Ibid., pp.113-14; my italics - BS.) Sect xxx - Lastly; if length of days be thy portion make it not thy expectation. Reckon not upon long life; think every day the last, and live always beyond thy account. He that so often surviveth his expectation lives many lives, and will scarce complain of the shortness of his days. Time past is gone like a shadow; make time to come present. Approximate thy latter times by present apprehensions of them: be like a neighbour unto the grave, and think there is but little to come. And since there is something of us that will still live on, join both lives together and live in one but for the other. He who thus ordereth the purposes of this life, will never be far from the next; and is in some manner already in it, by a happy conformity, and close apprehension of it. And if as we have elsewhere declared,* any have been so happy, as personally to understand christian annihilation, extacy, exolution, transformation, the kiss of the spouse, and ingression into the divine shadow, according to mystical theology, they have already had an handsome anticipation of heaven; the world is in a manner over, and the earth in ashes unto them. (Idem.) Notes: *[3] In his treatise of Urn burial. Some other parts of these essays are printed in a letter among Browne’s Posthumous Works. Those references to his own books prove these essays to be genuine Dr J[ohnson]. (p.114.) [End of Christian Morals]

Editor’s note (Simon Wilkin - 1835 Edn.): ‘The original edition of the Christian Morals by Archdeacon Jeffery [i.e., edited by] was printed at Cambridge in 1716 and is one of the rarer of Sir Thomas’s detached works Dodsley in 1756 brought out a new edition with additional notes and a life by Dr Johnson It has been said that Dr Johnson inserted in the Literary Magazine a review of the work but I have not been able to find it. The Sixth Volume of Memoirs of Literature contains a meagre account of the Posthumous Works but no notice of the Christian Morals. / The latter portion of the Letter to a Friend is incorporated in various parts of the Christian Morals except some passages which are given in notes to the present edition together with some various readings from MSS in the British Museum.’ (From Sir Thomas Browne’s Works Including His Life And Correspondence[,] Edited by Simon Wilkin FLS, Volume IV, London: William Pickering; Norwich: Josiah Fletcher 1835 - copy available at Google Books - online.)

—copy available at Google Books - online. See also Christian Morals Published from the Original and Correct Manuscript of the Author by John Jeffery, DD, Arch Deacon of Norwich, With Notes Added to the Second Edition by Dr Johnson / Third Edition Originally Published in 1716 (1845) - available online [search > shortness.]

[ top ]

| The Engine of Owl-light (1987) | The Secret Scripture (2008) |

| Epigraph | Text |

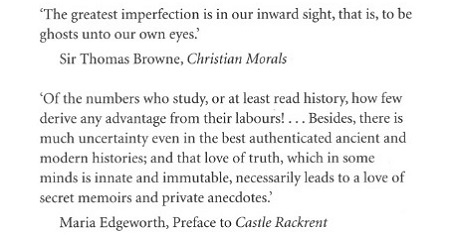

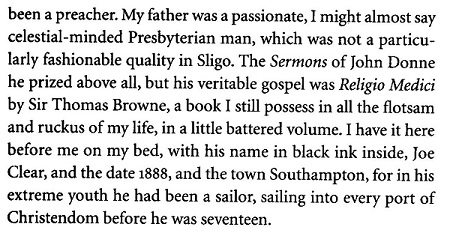

The Secret Scripture (2008) also has an epigraph from Sir Thomas Browne (Christian Morals, written in the 1670s; pub. 1716) - together with another from Maria Edgeworth (Preface to Castle Rackrent, 1800). Roseanne, the central character of Scripture, owns a copy of Religio Medici [1643; 1645] and quotes from it explicitly - explaining that it was a ‘veritable gospel’ to her father.

Note that the epigraph from Christian Morals is correctly ascribed in the front papers to in The Secret Scripture [as above], although that work [Christian Morals] is not included in the edition issued by Sampson & Low (London 1869) which is copiously cited in the text of the novel - a

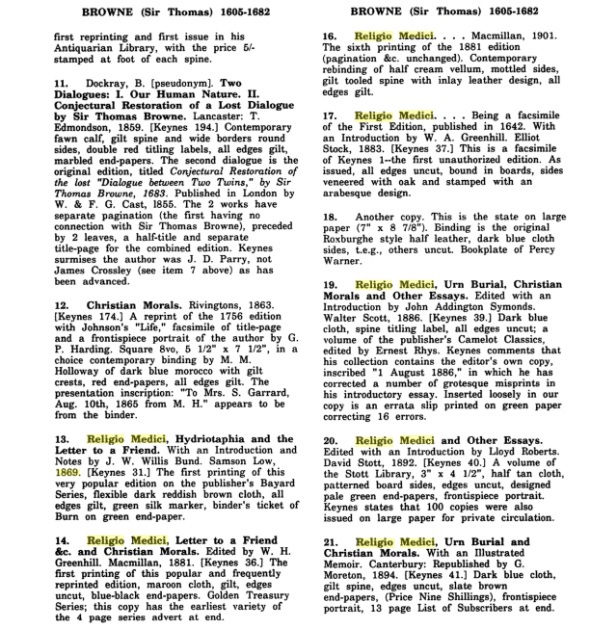

Note: The epigraph does indeed come from Christian Morals (1712; rep. with Life by Dr Johnson, 1756) - but note that Christian Morals is not included in the London edition of the works edited J. W. Willis Bund (London: Sampson & Low 1869) which is cited at some length as the volume which Roseanne McNulty has inherited from her father whose ’veritable gospel’ it was. A copy of that edition ‘the little volume’) is handed over to Dr. Grene and becomes, in that way, a crucial prop in the novel. See Dr. Grene’s description of the edition and its contents under “Allusions to Thomas Browne in The Secret Scripture” - as infra > Item 5].

It seems to follow that Barry has had access to more than one printed source of the works of Browne. It is also to case, however, that the epigraph for The Engine of Owl-light which is said there to come from Browne’s Hydrotaphia or Unr-buriall comes, in fact, from Christian Morals - and hence the same source as the epigraph to The Secret Scripture. On that basis it might be possible to infer that Barry has only seen Christian Morals in some edition of the works of Sir Thomas Browne other than the one published by Sampson in 1869. However, the extract from the first page of Medici Religio quoted by Dr. Grene in his perusal of the Sampson edition - as infra - makes it clear that this is indeed a work in the possession of the author.

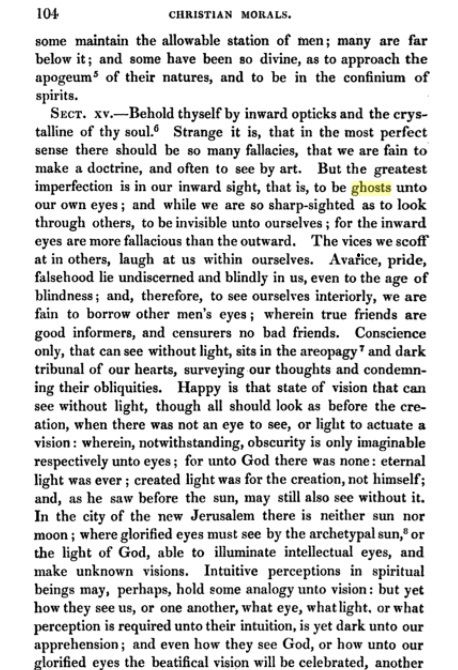

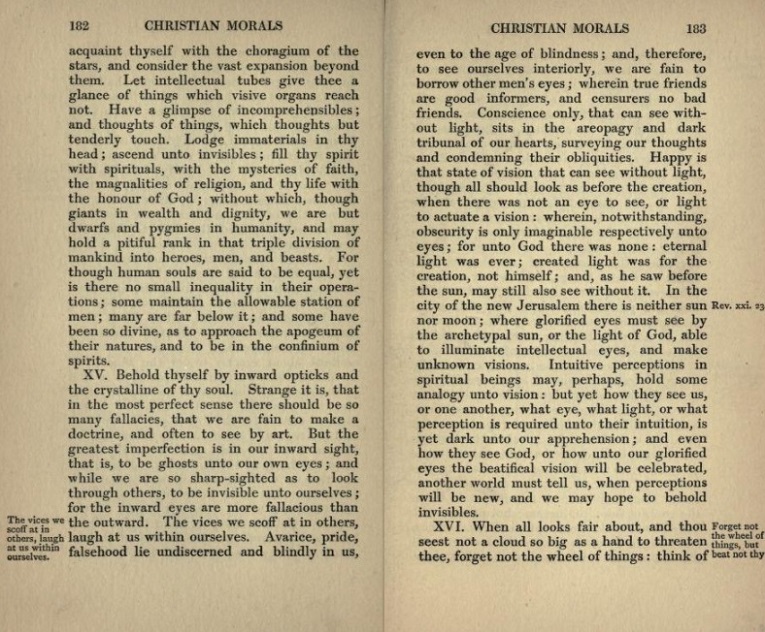

Page images from Sir Thomas Browne’s Works, ed. S. Wilkin (London 1835), Christian Morals, Pt. III [Part the Third] Transcription: Behold thyself with inward opticks and crystalline of they soul. Strange it is, that in the most perfect sense there should be so many fallacies, that we are fain to make a doctrine, and often to see by art. But the greatest imperfection is in our inward sight, that is, to be ghosts unto our own eyes and while we are sharp-sighted as to look through others, to be invisible unto ourselves; for the inward eyes are more fallacious than the outward.

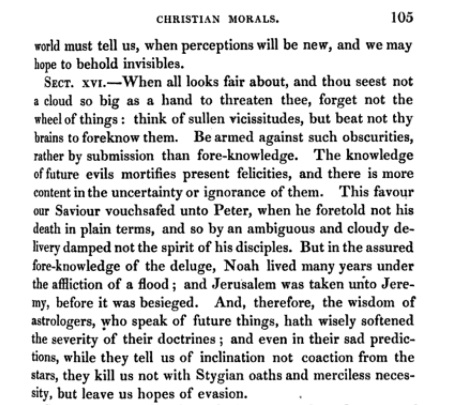

Available at Google Books - online; accessed 24.05.2017. Sect xiv: Live unto the dignity of thy nature, and leave it not disputable at last, whether thou hast been a man; or since thou art a composition of man and beast, how thou hast predominantly passed thy days, to state the denomination. Unman not, therefore, thyself by a bestial transformation, nor realize old fables. Expose not thyself by four footed manners unto monstrous draughts, and caricature representations. Think not after the old Pythagorean conceit, what beast thou mayst be after death. Be not under any brutal metempsychosis, while thou livest and walkest about erectly under the scheme of man. In thine own circumference, as in that of the earth, let the rational horizon be larger than the sensible, and the circle of reason than of sense: let the divine part be upward and the region of beast below; otherwise ‘tis but to live invertedly, and with thy head unto the heels of thy antipodes. Desert not thy title to a divine particle and union with invisibles. Let true knowledge and virtue tell the lower world thou art a part of the higher. Let thy thoughts be of things which have not entered into the hearts of beasts; think of things long past and long to come: acquaint thyself with the choragium of the stars and consider the vast expansion beyond them. Let intellectual tubes give thee a glance of things which visive organs reach not. Have a glimpse of incomprehensibles; and thoughts of things, which thoughts but tenderly touch. Lodge immaterials in thy head; ascend unto invisibles; fill thy spirit with spirituals, with the mysteries of faith, the magnalities of religion, and thy life with the honour of God; without which, though giants in wealth and dignity, we are but dwarfs and pygmies in humanity, and may hold a pitiful rank in that triple division of mankind into heroes, men and beasts. For though human souls are said to be equal, yet is there no small inequality in their operations; some maintain the allowable station of men; many are far below it; and some have been so divine, as to approach the apogeum of their natures, and to be in the confinium of spirits. (p.104.)

Sect xv: Behold thyself by inward opticks and the crystalline of thy soul. Strange it is, that in the most perfect sense there should be so many fallacies that we are fain to make a doctrine, and often to see by art. But the greatest imperfection is in our inward sight, that is to be ghosts unto our own eyes; and while we are so sharp-sighted as to look through others, to be invisible unto ourselves; for the inward eyes are more fallacious than the outward. The vices we scoff at in other, laugh at us within ourselves. Avarice, pride, falsehood lie undiscerned and blindly in us, even to the age of blindness and therefore to see ourselves interiorly we are fain to borrow other men’s eyes wherein true friends are good informers and censurers no bad friends. Conscience only, that can see without light sits in the areopagy and dark tribunal of our hearts, surveying our thoughts and condemning their obliquities. Happy is that state of vision that can see without light, though all should look as before the creation, when there was not an eye to see or light, to actuate a vision: wherein, notwithstanding, obscurity is only imaginable respectively unto eyes; for unto God there was none: eternal light was ever; created light was for the creation, not himself; and as he saw before the sun, may still also see without it. In the city of the new Jerusalem there is neither sun nor moon; where glorified eyes must see by the archetypal sun [n8] or the light of God able to illuminate intellectual eyes and make unknown visions. Intuitive perceptions in spiritual beings, may, perhaps hold some analogy unto vision: but yet how they see us, or one another, what eye, what light, or what perception is required unto their intuition, is yet dark unto our apprehension; and even how they see God, or how unto our glorified eyes the beatifical vision will be celebrated, another world must tell us, when perception will be new, and we may hope to view invisibles. (pp.103-05; my italics - BS.)

See another edition as Sir Thomas Browne’s Works, ed. S. Wilkin, Vol. IV (London: Henry G. Bohn MDCCCLVII [1837]) - Christian Morals, Pt. III [Part the Third]; available at Internet Archive - online.]

[ top ]

| Page images from Religio Medici and Other Essays, ed. by D. Lloyd Roberts, MD, FRCP (Manchester: Sherratt & Hughes 1902) | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Available at Internet Archive - online; accessed 24.05.2017. |

| [ See another edition as Sir Thomas Browne’s Works, Vol IV: Repertorium - letter to a Friend - Christian Morals - Miscellaneous Tracts - and Unpublished Papers (London: William Pickering 1835 - online; accessed 08.06.2017. ] |

[ top ]

| Epigraph | Text |

| In-text allusions to Religio Medici in The Secret Scripture (2008) | |||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| [ See page-images of Religio Medici [... &c.] (London: Sampson Son & Marston 1869) - as infra. ] | |||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

[ top ]

|

|

|

| —Available in Internet Archive - online. |

| Text version |

| Religio Medici and Other Essays by Sir Thomas Browne, ed. D. Lloyd Roberts (Manchester: Sherratt & Hughes 1902) |

| CERTAINLY that man were greedy of life who should desire to live when all the world were at an end; and he must needs be very im- patient who would repine at death in the society of all things that suffer under it. Had not almost every man suffered by the press, or were not the tyranny thereof become universal, I had not wanted reason for complaint: but in times wherein I have lived to behold the highest perversion of that excellent invention, the name of His Majesty defamed, the honour of Parliament depraved, the writings of both depravedly, anticipatively, counterfeitly imprinted: complaints may seem ridiculous in private persons; and men of my condition may be as incapable of affronts,, as hopeless of their reparations. And truly had not the duty I owe unto the importunity of friends, and the allegiance I must ever acknowledge unto truth, prevailed with me; the inactivity of my disposition might have made these sufferings continual, and time, that brings other things to light, should have satisfied me in the remedy of its oblivion. [xxxviii] But because things evidently false are not only printed, but many things of truth most falsely set forth; in this latter I could not but think myself engaged. For though we have no power to redress the former, yet in the other the reparation being within ourselves, I have at present represented unto the world a full and intended copy of that piece, which was most imperfectly and surreptitiously published before. |

| Available at Internet Archive - online. |

|

|

|

|

Browne Bibliography: Colbeck Special Collections at the Library of the University of British Columbia:

[ top ]

| Benedict Anderson (Imagined Communities, 1983): Anderson quotes a passage from Browne’s Urn-Buriall, viz., - ‘Even the old ambitions had the advantage of ours, in the attempt of their vainglories [...] whereby the ancient Heroes have already out-lasted their Monuments and Mechanicall preservations [..., &c.]’, in Imagined Communities (1983; Verso 1991). |

|

|

|

[ top ]

| A Selection of Sentences and Aphorisms by Sir Thomas Browne |

|

| —Sundry sources. |

[ top ]

| Sir Thomas Browne | Maria Edgeworth |

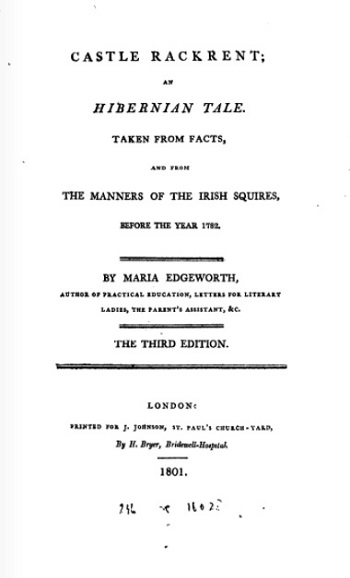

Maria Edgeworth: Barry employs an excerpt from the Preface to Castle Rackrent (1800) as an epigraph for The Secret Scripture (2008), along with another from Sir Thomas Browne [as supra].

[ top ]

[ Maria Edgeworth, Castle Rackrent: An Hibernian Tale, taken from the facts and from the Manners of the Irish Squires before the Year 1782 [Third Edition] (London: J. Johnson, St. Paul’s Church-yard 1801), t.p. & pp.[iii]-iv]

[ Available at Internet Archive - online; accessed 05.06.2107. ] [ Available at Internet Archive - online; accessed 05.06.2107; for full-text copy of the Preface to Castle Rackrent, see under Maria Edgeworth > Quotations - as attached. ]

[ . ]

| [ See further pages-images from the Preface to Castle Rackrent (1801 Edn.) - as attached. For full-text copy of the Preface, along with page images, see under Maria Edgeworth > Quotations - infra; or as attached. ] |

| [ top ] |