Life

| ?1820-90 [Dionysius Lardner mat. Boursiquot; Bourcicault]; b. 26 [but vars. 20, 27 Dec. 1820; also 1822], at 28 Middle Gardiner St. [vars. 47 Lwr. Gardiner St.; 28 Mid. Gardner St.], Dublin, the son of Anne Boursiquot (dg. of Rev Charles Darley, first Prof. of English Lit. at Queen’s College, Cork, and niece of George Darley of Nepenthe; the Darley’s being related the Guinness family by marriage and residence of Wicklow nr. the Scalp - with memories of the 1798 Rebellion), and Dionysius Lardner, rather than her wine-merchant husband, 26 years her senior; ed. Univ. College School, where he met Charles Lamb Kenney, a life-long friend, and son of the dramatist James Kenney; returned to Dublin with his mother in 1836, and completed his education at Dr Geoghegan Academy, St. Stephen’s Green (where he was a classmate of William Howard Russell); he left Dublin in 1837 to work with his father as a civil engineer on the London-Harrow line; quit engineering for provincial acting under the name Lee Moreton in 1838; and appeared at Cheltenham and Brighton in the stage version of Lover’s Rory O’More, which influenced his own Arrah-na-Pogue; produced London Assurance at Covent Garden in 1841, aged 21 (or 18 by his own account); Old Heads and Young Hearts (Haymarket Th., 1844), produced 24 plays in the first five years, among them considered ‘the most amusing five-act production that has been seen for years’ by the Times critic; |

| produced The Corsican Brothers (1851), in which Louis dei Franchi dies for the honour of a woman he loved but could not have; also Marguerite and Faustus (1852) and La Dame de Picque, or The Vampire (1852), The Phantom, melodrama, regarded as ‘extreme point of inanity’ by Examiner critic (19 June 1852); seduced Agnes Robertson, the ward of Charles Kean, and eloped and married, moving to America, in 1853 - having a son [his third] and namesake, Dion George Boucicault (Jnr.; 1859-1929), who became a successful life-long actor who spent much time in Australia; produced The Octoroon (1859), dealing with slavery, and based on Mayne Reid’s Louisiana novel Quadroon (1856); wrote and produced The Poor of New York (1857), later repeated successfully in in London, Birmingham, Liverpool, &c., on variant title and with variant local details; encouraged by Augustin Daly to write comedies on Irish themes; produced The Colleen Bawn; or, The Brides of Garryowen (New York 1860; Adelphi, Sept. 1860) based on Griffin’s The Collegians (1829) - premiered at Miss Laura Keene’s Theatre, NY, 27 March 1860, with Keene as Anne Chute and Boucicault as Myles na Coppaleen [Ir. gCopalín/Copaleen]; the same rendered as an opera by Sir Julius Benedict, with Boucicault’s word, emended by John Oxenford (Boosey, 1861); |

| Boucicault became the first dramatist in England to received a royalty with a production of The Octoroon (Adelphi 1861); wrote Arrah-na-Pogue (Dublin 1864; London 1865), for which he devised the part of “Myles na Gopaleen” to be played by himself; regarded the role as an antidote to ‘the clowning character, known as “the stage Irishman”, which it has been [his] vocation, as an artist and as a dramatist, to abolish’; wrote The Long Strike (NY 1866), produced After Dark, A Tale of London Life (NY 1868), involving the rescue of its heroine from the path of a train; The Rapparee (1870), set after the Battle of the Boyne, is a political melodrama of the Wild Geese, in which an Irish traitor (Ulick MacMurragh) is finally dispensed in single combat by an Irish hero (Roderick O’Malley), who is ultimately pardoned by King William, while de Ginckel honourably distains the traitor’s aid; produced The Shaughraun (Wallack’s Theatre, 14 Nov., NY 1874), the latter two especially being enormously successful; returned to America, 1872; petitioned Disraeli by letter for release of Irish political prisoners, 1 Jan. 1876; wrote The O’Dowd, or Life in Galway (1880), a piece supporting Parnell and the Land League agitation; |

|

a munificent spender, Boucicault spent his latter years teaching acting, with nothing of his former fortune; in 1881 he was to ready to produce Wilde’s Vera in London with Mrs. Beere in the lead, but it was halted by official pressure following the assassination of Alexander II in March; fell under suspicion following sudden death of his first wife, a wealthy Frenchwoman who died in a fall in the Alps; m. actress Louise Thorndyke, 1888, repudiating his common-law wife Robertson by whom he had had four children, all of whom were on the stage; spoke in defence of Oscar Wilde at his trial; d. 18 Sept., USA; to the question, was he Irish?, Boucicault reputedly answered, ‘Nature did me that honour’; there is a caricature by Harry Furniss; The Shaughraun revived at the Abbey with Cyril Cusack in the lead, 31 Jan. 1967 and again in 2004 with Adrian Dunbar; The Colleen Bawn revived at the Abbey in 1998 under the direction of Conall Morrison, and again at at the Project Arts Centre, Dublin (July-August 2010); Arrah-na-Pogue was revived at the Abbey with Aaron Monaghue as Shaun the Post, Jan. 2011, in conjunction with a children’s workshop; The Octaroon (1859)was adapted [curated] for “Drama on Three”, BBC3 by Mark Ravenhill (29 April 2012). ODNB NCBE DIB DIW OCEL OCAL RAF FDA MKA OCIL WJM

|

|

|

|

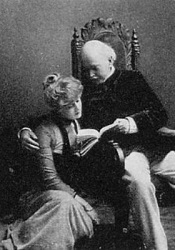

| Centre photo: Boucicault with Louise Thorndyke | ||

| Marriage lines: |

[Boucicault] married a wealthy widow and returned from his honeymoon a wealthy widower, and in 1885, while on tour in Australia, he married a young member of his company while maintaining that he never legally married his second wife and leading lady Agnes Robertson (Hogan 21-23, 44-45). |

| See Maureen Murphy, ‘Dion Boucicault: Showman and Shaughraun’, in Ilha do Desterro, 73, 2 (May-Aug. 2020), pp.137-44 - online. |

[ top ]

Works| First performances* | ||||

|

||||

| Published Edns | ||||

|

||||

|

||||

| Collected Editions | ||||

|

||||

| Prompt books | ||||

|

||||

| Miscellaneous | ||||

|

||||

See also Sir Julius Benedict, The Lily of Killarney: Opera in Three Acts. The Words by Dion Boucicault and John Oxenford, ed. J. Pitman (London & New York: Boosey & Co. 1861) - cited in Seamus Deane, Strange Country: Modernity and Nationhood in Irish Writing Since 1790 (Oxford 1997), p.63 [& n.]

| See list of Boucicault’s works on Victorian Web - online, or as copy - attached. |

[ top ]

Criticism| Monographs |

|

| Articles, &c. |

|

|

| General reading |

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Deirdre McFeely, Dion Boucicault: Irish Identity on Stage (Cambridge UP 2012) - Contents: Introduction [1]; 1. Becoming Boucicault; 2. Nationalism Race and Class in The Colleen Bawn [13]; 3. Music, Myth and Censorship in Arrah-na-Pogue [29]; 4. Alternative Readings: The Rapparee and Daddy O’Dowd [59]; 5. The Politics of Exile: The Shaughran in New York [77]; 6. “Audiences are not political assemblies”: The Shaughran in London [107]; 7. Supporting the Land League: The O’Dowd [139]; 8. Towards an Irish National Drama [173]; Appendix [184]; Notes [187]; Bibliography [207].Ills. include Playbill for Arrah-na-Pogue (Dublin, 10 November 1864) [TCD Lib.]; Front cover of ‘Wearing of the Green’ (Philadelphia, 1865) [Pierpont Morgan Lib.]; Dion Boucicault statuette by John Rogers [NGI]; Alfred Bryan cartoon of Dion Boucicault and Benjamin Disraeli from Entr’acte and Limelight: Theatrical and Musical Critic and Advertiser (15 January 1876); Vanity Fair ‘Spy’ print of Dion Boucicault (16 December 1882).

(Available at Google Books - online; accessed 23.09.2012; see also front-matter PDF at Cambridge Univ. Press - online; accessed 23.09.2012.)

[ top ]

Commentary

Allardyce Nicoll, A History of Late 19th-century Drama, 1850-1900 [q.d.], Vol. 1: ‘All of this was before the startling revolution introduced by Boucicault. In the year 1859, when he took his Colleen Bawn (Adel. 1860) to Webster, he made a novel proposal; instead of asking for a lump sum, he suggested sharing terms - and found himself eventually richer by £10,000 [...] the practice did not become universal till the eighties.’ Nicoll cites Townsend Walsh, The Career of Dion Boucicault (NY 1915). The Shaugraun was particularily interesting as an example of new scene change techniques with - according to the directions - the prison ‘mov[ing] off [to] show the exterior of tower, with Conn clinging to the walls and Robert creeping through the orifice’, an effect depending on a man ‘inside boxed wall’ which moves on a pivot. (p.69.)

Joseph Holloway writes that Dion Boucicault’s Irish dramas were ‘nowadays used simply to show off the Irish comedian or the Irish character actor’ (Journals, May 1900).

Richard Fawkes, Dion Boucicault: A Biography, with foreword by Donald Sinden (Quartet 1979), 274pp., with 8 pages of plates: ‘Boucicault and Arrah-na-Pogue’: ‘After the first night of Omoo [24 Oct 1864], Boucicault crossed the Irish Channel to Dublin for the staging of his next new piece, Arrah-na-Pogue, at the Theatre Royal. When the played opened on 7 November, he appeared as Shaun the Post and Agnes playes Meelish (“Arrah-no-Pogue, or Arrah of the Kiss”). It was received with wild enthusiasm, and Boucicault became the idol of the Dublin public, cheered in the streets and visited in his hotel by well-wishers and people who just wanted to look at him. Two other Dublin theatres mounted simultaneous productions of The Colleen Bawn in his honour.’ [Cont.]

Richard Fawkes (Dion Boucicault: A Biography, 1979) - cont.: ‘In Arrah-na-Pogue, Boucicault turned for the second time to his homeland for inspiration. Although there are definite affinities with Samuel Lover’s novel Rory O’More (a dramatization of which Boucicault had played in as a young actor in Cheltenham and Brighton) Arrah-na-Pogue is, in almost every respect, that rarity, an original Boucicault play. Based on historical events which took place during the Fenian rebellion of 1798, its incidents and characters are an obvious attempt to cash in on the popularity of The Colleen Bawn, but, popular though it was, the result is in many ways inferior. The hero, Beamish MacCoul, is a dashing but stereotypical rebel; Arrah and Fanny, the two women, possess little of the vitality of Eily O’Connor or Anne Chute; and Shaun the Post (the Myles character, again played by Boucicault) has little of Lyles’s interest until later in the play, when he is captured and forced to become the rogue everyone expects him to be. However the play possesses some clever and effective dialogue and is well-constructed with notable scenes - particularly Shaun’s escape from prison (which was added after the Dublin production) and the trial, in which Shaun mocks British justice. G. B. Shaw, who knew Boucicault’s plays well, paid him the compliment of basing the trial scene in The Devil’s Disciple on Shaun’s trial, and there are many parallels between the two, even down to the dialogue. General Burgoyne is the counterpart of Boucicault’s Irish gentleman Colonel O’Grady; Major Coffin is very similar in attitude and ineptitude to Shaw’s Major Swindon; and several other incidents in the Boucicault play found their way into Shaw’s.’ [Cont.]

Richard Fawkes (Dion Boucicault: A Biography, 1979) - cont.: ‘The Dublin verson of the play was not the version Shaw came to know, for much of it was rewritten after the Dublin performances. [Quotes:] “I was present at the first performance”, recalled Percy Fitzgerald. “It was an altogether different piece from what it afterwards became [...] in the last act [...] there was an Irish duel [...] meeting Boucicault on the next day [... t]o my surprise he quietly pointed out that the last act would never do and must come out altogether. The rest must be rewritten, the interest concentrated. He was glad he had made the experiment [...] an instructive lesson in the craft [...] when it was reproduced in London, I could scarcely recognise it.” John Brougham, who played The O’Grady in both the original and the London productions, could not understand, after the reception in Dublin, why Boucicault should want to alter such an obvious success [but] was forced to admit [at a reading of the revised play to the cast] that it was a much better play, demonstrating Boucicault’s assertion that ‘plays are not written they are rewritten’. [...] Arrah-na-Pogue, revised and tightened, opened at the Princess’s in March and became the hit of the season, running for 164 nights [155-58]. Fawkes further discusses the element of co-authorship with Edward Howard House, whom Boucicault named as co-plaintiff in his suit against John Berger, who had serialised the Arrah story in his London Herald. When the play was registered in America, he was given as co-proprietor, and Boucicault later assigned him all the American rights in the play. A copy of the song “The Wearing of the Green” was published in America with both their names attached as authors [157-58].’ [Cont.]

Richard Fawkes (Dion Boucicault: A Biography, 1979) - cont.: ‘“The Wearing of the Green”, a traditional Dublin ballad; Boucicault updated it to produce an anti-English lyric and the song became the unofficial anthem of the Irish freedom movement; after a revival of the play two years later, in which Agnes and Boucicault repeted their roles, the Clerkenwell explosion, which killed 12 and injured 120, led to its being banned throughout the British empire and when Boucicault returned to Dublin with the play he was asked to drop the song on the grounds of expediency. [158]. Fawkes writes of Arrah-na-Pogue’s Dublin premier: ‘After the first night of Omoo [in October 1864].. Boucicault cross the Irish Channel to Dublin for the staging of his next new piece, Arrah-na-Pogue at the Theatre Royal [...] opened 7 Nov. [...] [Boucicault] appeared as Shaun and Agnes played Arrah Meelish [...] it was received with wild enthusiasm, and Boucicault became the idol of the Dublin public, cheered in the streets and visited in his hotel [...] Two other Dublin theatres mounted simultaneous productions of The Colleen Bawn in his honour. [...] Although definite affinities with [...] [Lover’s] Rory O’More [...] it is that rarity, an original Boucicault play. [...] The Dublin version was not the version Shaw came to know, for much of it was rewritten after the Dublin performances. [...] dropping the last-act duel and condensing the plot [and adding] a ‘sensation’ scene in which Shaun escapes by climbing the ivy-covered tower wall. [Note, this piece of stage-craft is illustrated by a diagram and an engraving in the Revells History. Shortly after the play’s London opening on 22 March 1865, Boucicault sued John Berger, ed. of London Herald, for serializing the Arrah story &c.’ (Dion Boucicault, pp.154-56). Bibl., incls. 18 journalistic pieces including interviews by Boucicault, commencing with ‘The Art of Dramatic Composition’ in North American Review, Vol. 126 (Jan. 1878). 14 articles on Boucicault cited include Bryan MacMahon, ‘The Colleen Bawn’, in Ireland of the Welcomes, vol. 24 (1975), and 4 pieces by Albert E. Johnson including ‘The Birth of Dion Boucicault’, in Modern Drama (Sept. 1968), and ‘Dion Boucicault learns to act’, in Players, Vol. 47 (Dec-Jan. 1973). Full-length studies specifically on Boucicault are, David Krause, ed., The Dolmen Boucicault (Dublin 1964); Robert Hogan, Dion Boucicault (NY 1969); Charles Lamb Kenney, The Life and Career of Dion Boucicault (NY 1883), written in fact by Boucicault himself; Townsend Walsh, The Career of Dion Boucicault (NY 1915). Other sources include Joseph Francis Daly , The Life of Augustin Daly (NY 1917); George Rowell, Victorian Dramatic Criticism (London 1971), and The Victorian Theatre, A Survey (London 1956); Oscar Wilde, Letters, ed. Rupert Hart-Davies (London 1962); and Charles Dickens, Letters (London 1893). There is no dramatic bibliography of his works.

[ top ]

Kevin Rockett, et al., eds, Cinema & Ireland (1988), makes extensive reference to his melodramatic style and its consequences for Irish movies; Arrah-na-Pogue, a Kalem production of 1911, was regarded as a controversial drama of 1798. Aspects of the play are fully discussed at pp.213-220. Also notes that filming of the Colleen Bawn (Kalem 1911) was interrupted by pulpit threats against ‘tramp photographers’ from the local parish priest, who was subsequently transferred to another parish by his bishop, making filming possible; Boucicault supposedly metaphorosed ‘begorrah’ into authentic social being; notes popularity of the play and the use of a sensational drowning scene in stage versions; remarks on intimate relation between language and politics in it; discusses the unreconstructed brogue of Eily and embarrassment to Hardress; contemporary review of Kalem film praises the educative value of their on-site filming of ‘the great dramatist’ [i.e. Boucicault]; attempted drowning; London poster for Boucicault’s Colleen Bawn listed in bold face the beauty spots Lake of Killarney and Gap of Dunloe &c as components of the story; original play in that ‘peasant character develops as personality in the course of the action’; further, ‘psychological rather than external characterisation [was] taken up and brought to perfection by Boucicault’, according to Frank Rahill, in The World of Melodrama (Penn UP 1967), p.189] (See Index, Rockett, op. cit.). Note also The Lily of Killarney (1934). [See also remarks by Luke Gibbons, in Cinema & Ireland, under Quotations, infra.)

Cheryl Herr, For the Land They Loved (Syracuse UP 1991): ‘By the time that Dion Boucicault, Ireland’s greatest writer in this [melodramatic] genre, wrote The Fireside Story of Ireland (1881), it was perhaps unsurprising to readers of history that [he] divided the story into four sections - four acts, really - each with its own high conflicts and stylised denouements. What we find here are tableaux from Irish history, moments in themselves so hortatory that they need little or no language, merely histrionic gesture, to communicate the depth of injustices committed against the beleaguered heroine, Cathleen ni Houlihan.’ (p.48.)

Stephen Watt, on Robert Emmet, in Joyce, O’Casey, and the Irish Popular Theater (1991): ‘To begin, both Boucicault’s Robert Emmet and [J. B.] Whitbread’s plays [...] about heroes of Ireland’s past contain nationalist and tragic sentiments common to their antecedents in other eras and cultures when historical drama thrived. [...] Plays like Robert Emmet provided all of these theatrical and ideological attractions [...] relies heavily on melodramatic opposition between Irish nationalism and its typical opponents (traitors and tyrants) [...] Robert Emmet is a heroical tragedy [...] in Emmet, the informer Quigley, the nobel Lord Kilwarden, Emmet’s loyal friend Andy Devlin, and Emmet himself are killed. To provide a comic ending for any of his characters, Boucicault is forced to alter well-known historical fact which he does in the case of Michael Dwyer and Anne Devlin, who escape to America [..] before Emmet is executed - but only after Anne has suffered brutal treatment by the villainous Major Sirr and helped Dwyer kill Quigley. [...] Blarney becomes eloquence [...] One such instance is Emmet’s comparison of the present rebellion with Ireland’s heroical past; “If you [his men] stand by me you must march as children of Erin, as United Irishmen, whose one hope is freedom; not as banditti, whose sole object is plunder. The green flag that led our countrymen at Fontenoy under Sarsfield has never been dishonored, and its shall not be so under Robert emmet, so help me God.” [...] locates the rebellion within the chronicles of a glorious national past [...] Emmet compares Irish rebellion to French revolution, to America’s struggle for independence, and other appropriately honorable risings. [...] a Christ-figure betrayed by his own men, a Napoleon, Brutus, Washington. The central focus is on Emmet [but] Anne Devlin and Tiney Wolfe display their courage [...] the stage villains originate in Boucicault’s earlier plays [...] their success in bringing Emmet to the firing squad [sic; [...] ] their Judas-like betrayal [...] Major Sirr, opposed to the noble British officer (Norman Claverhouse) is the darkest of all Boucicault’s villains [...’; 77-80]. Further, ‘[On] 1 Jan. 1876, in what may have been partly a publicity stunt, Boucicault wrote an open letter to PM Benjamin Disraeli demanding the release of Irish political prisoners from British prisons’ (p.72). Watt also notes that The Octaroon and The Shaughraun ran for a dozen performances each in 1923 (p.87).

Grevep Lindop, ‘Marriage of expedience’, review of Dion Boucicault, London Assurance (Royal Exchange Th., Manchester, in Times Literary Supplement (17 Dec. 2004): ‘[...] London Assurance belongs to an earlier, very different phase of his work [that The Colleen Bawn, 1860]. It was written in 1841, when Boucicault was a penniless, twenty-one-year-old adventurer newly arrived in England and determined to impose himself on the London stage. While The Colleen Bawn looks forward to Synge and O’Casey, London Assurance commandeers the comic conventions of Sheridan and Goldsmith, pushing them to extravagant lengths surreally within earshot of The Importance of Being Earnest. Opportunities to see this odd, exuberant play are rare, so it is good to find Jacob Murray directing a full-blooded, fast-paced production, which communicates the play’s youthful impudence (the “assurance” of the title) and leads its cast of grotesques a lively dance. / London Assurance gives us the outsider’s view of English society. [...] As Dazzle cons and improvises his way from Belgravia to Gloucestershire, it is tempting to see him as Boucicault’s wry self-portrait, the more so when he acts incidentally as deus ex machina, resolving other characters’ problems without finding a niche for himself. Langtree gives him immense panache, but adds a tinge of desperation. His final confession that he has “not the remotest idea” who he is, beyond being a liver on credit, a backer of winners and “an epidemic on the trade of tailor”, adds a concluding touch of metaphysical strangeness.’ (See full text; gives synopsis of plot and characters.)

Maureen Murphy, ‘Dion Boucicault: Showman and Shaughraun’, in Ilha Desterro, 73, 2 (May-Aug. 2020): ‘[...] Boucicault developed a successful formula for dramatizing his romantic portrayal of Ireland with blushing colleens, broth of boys, genial parish priests, neat thatched cottages and songs and dances-all laced with a bit of poitin and patriotism. It was such a successful approach that Lennox Robinson felt that the distance between Boucicault’s Ireland and John Millington Synge’s Ireland created the riots that greeted The Playboy of the Western World during the Abbey’s 1911-1912 American tour (Robinson 1968, 95-96). / While Boucicault as showman exploited Irish nationalism and romanticism in The Colleen Bawn, Arrah-na-Pogue and The Shaughraun, plays more successful than Boucicault’s more polished Regency comedies like London Assurance (1841), it was Boucicault as creator of the characters of Myles na gCopaleen, Shaun the Post and Conn the Shaughraun who ensured the continued success of his Irish plays. Boucicault not only created the characters, but he also played the role of Conn the Shaughraun with great success. / Critics like David Krause (1964) and Robert Hogan (1969) have identified the origin of Boucicault’s Irish characters in the parasite-slave characters in Roman comedy; however, there were more recent antecedents in certain native Irish characters who appear in Irish pre-famine fiction and in the heroes of nineteenth-century American drama who appeared on the stage to dramatize American romantic nationalism. / [...]

Maureen Murphy (‘Dion Boucicault: Showman and Shaughraun’, 2020) - cont.: ‘Gerald Griffin’s Myles Murphy or Myles na gCopaleen, the shrew pony trader in The Collegians (1829) which was adapted by Boucicault as The Colleen Bawn in 1860, is a particularly good example of the native Irish hero. From his first appearance in the novel, Myles is the most attractive character in The Collegians. [...] Arguing that Myles is the first of a series of rogue heroes that is fully developed in Synge’s Christy Mahon, David Krause has described Myles as “a lazy, lying tramp, beyond any hope of reform, a horse-thief and ex-convict, poacher and poitin-maker who thumbs his nose at authority-in short, an irresponsible rogue who is the complete antithesis of Victorian respectability”. True for Conn but not for Myles. Myles is not a loafer. He is a shrewd horse-dealer who abandons his ponies to watch over his beloved Eily while she waits to be recognized as Creegan’s wife. He does this not out of laziness but out of loyalty.’ [Cont.]

Maureen Murphy (‘Dion Boucicault: Showman and Shaughraun’, 2020) - cont. [next para]: ‘Boucicault found the character of Myles in The Collegians and borrowed more from Griffin than his admirers admit; he found his model for Myles as hero in the popular American theatre. Familiar with the Myles type in Irish fiction, Boucicault found an American native hero in the Yankee, in Sam Patch, in Davy Crockett and in Mose the Bowery B’hoy, the protagonists of plays full of social idealism. American patriotism and Jacksonian democracy influenced Boucicault’s Andy Blake (1854), first play for the American stage and later his very successful adaptation of Les Pauvres de Paris, The Poor of New York (1857) where the character of Dan the Fireman was based on Mose. (Pure showman Boucicault had a fire engine arrive on stage at the last minute to extinguish the fire from which Dan emerged.) / A clear line can be drawn between the American Yankee hero and Boucicault’s Myles, Shaun/Conn characters.’ (See full-text copy - as attached.)

[ top ]

A Fireside Story of Ireland (London & Boston 1881) [pamphlet - beginning:] ‘Let me tell you the story of Ireland. It is not a history. When we speak of the history of a nation, we mean the biographies of its kings: the line of monarchs forming a spinal column from whcih historical events seem to spring laterally. The history of Ireland is invertebrake. It has no such royal backbone [...] The efforts of the Irish race to regain their country present a monotonous record of bloodshed extending over seven centuries, even to our own day: the last of these massacres occurred only eighty-three years ago. These convulsions are the only reigns into which the story of Ireland can be perspicaciously divided. They might be called Reigns of Terror.’ (Ibid.], quoted by Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representations of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century, Cork UP/Field Day 1996, p.155; op. cit., 2nd edn. 1881, [n.p.].) [Leerssen remarks: ‘This is almost worthy of Michelet. The clever and highly apposite use of the vertebrate metaphor makes it possible to link the chaos of Irish history to the [156] country’s oppression under foreign rule and loss of nationhood [...’ see long extract under Leerssen - infra.]

Further: ‘While other nations were thus advancing, by experiment and experience, towards a higher state of civilization [...] Ireland was not permitted to share in the progress. Her elder sisters of the British family seemed to regard her with indifference and contempt, as one fitted or a sordid life of servitude. / thus, like an untutored, neglected Cinderella, she has been confined in the out-house of Great Britain.’ (Quoted in Stephen Watt, Joyce, O’Casey, and the Popular Irish Theater, Syracuse UP 1991).

Abolish Stage Irishmen: ‘The fire and energy that consists of dancing around the stage in an expletive manner, and indulging in ridiculous capers and extravagancies of language and gesture, form the materials of a clowning character known as the “Stage Irishman” which it has been my invocation, as an artist and a dramatist, to abolish.’ (Quoted [in part] in Robert Hogan, Dion Boucicault, Twayne 1969; cited by Cheryl Herr, For The Land They Loved, Syracuse Press 1991 [q.p.].) Note: The foregoing quoted [more fully] in Luke Gibbons, ‘Romanticism, Realism and Irish Cinema’, Cinema and Ireland (Kent: Croom Helm 1987) [Chap. 7], p.212 - with the remark: ‘It must certainly come as news to a modern audience that Boucicault set out to abolish the stage Irishman! Yet his declaration is highly revealing in that it demonstrates clearly the cyclical (and self-defeating) nature of “realist breakthroughs” from the enclosing myths and “distortions” of romanticism in Ireland. For it was precisely Boucicault’s “realism” which the Abbey Theatre was later to dismiss as “the home of buffoonery and easy sentiment”, and of course it is now the Abbey and the general legacy of the Literary Revival which is seen, with revisionist hindsight, as the repository of “ancient idealism” and other forms of romantic self-deception.’ (idem.)

Beamish Mac Coul (the young Irish hero in Arrah-na-Pogue who has returned from America to lead his countrymen against the English, provides the model for the eloquent patriot of the later melodramas): ‘Oh my land! My own land! Bless every blade of grass upon your green cheeks! The clouds that hang over ye are the sighs of your exiled children, and your face is always wet with their tears’ (Quoted in Stephen Watt, Joyce, O’Casey, and the Popular Irish Theater, 1991, p.69; with discussion of The Colleen Bawn and Arrah-na-Pogue as linguistic drama; pp.66-67.)

Oscar Wilde: ‘He is a gentleman of refinement and a scholar ... Those who have known him as I have known him since he was a child at my knee know that beneath the fantastic envelope in which his managers are circulating him, there is a noble, earnest, kind and lovable man.’ (Quoted by Seán Ó hUiginn, Irish Ambassador, at dinner at unveiling of head of Wilde by Melanie le Brocquy, in Irish Chancery, Washington, 30 Nov. 2000.)

[ top ]

References

Dictionary of National Biography notes that his plays [are] invariably adapted from previous play or novel by another hand (viz, Octoroon taken from Reid’s Quadroon); also lists Dion Boucicault the Younger (1859-1929).

D. J. O’Donoghue, ed., Humour of Ireland (1894) lists Dion Boucicault/Dionysius Lardner Bourcicault; b. 26 Dec. 1822; ‘his Irish dramas are well known, and still considered the best of their kind. He was an admirable comedian, as well as a dramatic writer [...]’

W. S. Gilbert [of Gilbert & Sullivan] referred to Boucicault’s Shaughraun (DL 1875), in Patience (1881) as ‘the pathos of Paddy, as rendered by Boucicault.’ (Revell’s History of the Stage, Vol. vi., 261).

John Parker, ed., Who’s Who in the Theatre (1930): his daughter Nina Boucicault (1867-1950) was a successful actress, noted in she was the first to play Peter in Barrie’s Peter Pan (1904), and first appeared on stage as Eily in The Colleen Bawn; her brother Darley George (1859-1929, called ‘Dot’), son of Boucicault and Agnes Robertson, who married Irene Vanbrugh, appeared in plays by Pinero and A. A, Milne.

Peter Kavanagh, The Irish Theatre (Tralee: The Kerryman 1946), Dion Boucicault; b. 20 Dec., Lr. Gardiner St.; Boursiqnot [sic]; Dr Lardner took a parental interest in him; first play, London Assurance (Covent Garden 4 March 1841), as Lee Morton; The Irish Heiress (Feb. 1842); Alma Mater, or A Cure of Coquettes (19 Sept. 1843); Woman (Covent Garden, 2 Oct. 1843); Old Heads and Young Hearts (Haymarket Th., 18 Nov. 1844) [which the Times called ‘the most amusing five-act production that has been seen for years’]; A School for Scheming (Haymarket Th., 4 Feb. 1847); Confidence (Haymarket Th., 2 May 1848); The Knight of Arva (Haymarket Th., 22 Nov. 1848); The Broken Vow (Olympia, 1 Feb. 1851); The Corsican Brothers (Princess Theatre, 1851), adapt.; The Queen of Spades (Drury Lane, [?] April 1851), adapt. libretto; La Dame de Pique [, ]or The Vampire (Princess Th., 14 June 1852), afterwards The Phantom, melodrama, regarded as ‘extreme point of inanity’ by Examiner of 19 June 1852; The Prima Donna (Princess Th., 18 Sept. 1852); Genevieve or The Reign of Terror (Adelphi Th., June 1853), after Dumas; The Fox-Hunt, or Don Quixot the Second (Burtons NY, 23 Nov. 1853; afterwards The Fox-chase); Andy Blake (NY, n.d., afterwards The Dublin Boy); Louis Onze (NY, n.d.); Eugenie (Drury Lane, 1 Jan. 1855); Janet Pride (Adelphi 5 Feb. 1855 - prev. in US); Blue Belle (?, 1856); George Darville (Adelphi Th., 3 June 1857); The Colleen Bawn (Adelphi 16 Sept. 1860); The Octoroon (NY Winter Gdn, Dec. 1859; London Adelphi, 18 Nov. 1861); The Life of an Actress (Adelphi Th., 1 March 1862); Dot (Adelphi Th., 14 April 1862), adapt. Dickens; The Relief of Lucknow (Astley’s Th., 1862); The Trial of Effie Deans (Westminster Th., 26 Jan. 1863); The Streets of London (St. James Th., 5 Aug. 1864), adpt. from French; Arra[h] -na-Pogue or The Wicklow Wedding (Dublin Theatre Royal, 5 Nov. 1864); The Parish Clerk (Manchester, May 1866); The Long Strike (London Lyceum, Sept. 1866); The Flying Scud, or A Four-Legged Fortune (Holborn Th., 6 Oct. 1866); Hunted Down (St. James Th., Nov. 1866); After Dark, A Tale of London Life (Princess Th., 12 Aug 1868); Presumptive Evidence (Princess Th., May 1869); Formosa (Drury Lane, Aug. 1869); Paul Lafarge, A Dark Night’s Work, and the Ra[p]aree (Princess Th., 1870); Jezebel or the Dead Reckoning (Holborn Th., Dec. 1870), adapt. from Masson and Bourgeois’ Le Pendu; Night and Morning (Gaiety 1872); Led Astray (Gaiety, June 1874), from La Tentation by Octave Feuillet; The Shaughraun (Drury Lane, 4 Sept. 1875). OTHER PIECES are, Love in a Maze (1850-51); Pierre The Foundling (1854), adpt.; The Willow Copse (1859); To Parents and Guardians (Astlet’s 22 Dec. 1862); A Lover by Proxy (1865); Rip Van Winkle (1865); How She Loves Him (1867); Elsie (1871); A Man of Honour (1874); Forbidden Fruit (1877); Norah’s Vow (1878); Rescued (1879); The O’Dowd ([Adelphi] 1880); A Bridal Tour (Hay., 2 Aug 1880); Mimi (1881); The Amadan (1886); Robert Emmet (1884 ); The Jilt (1886); The Spae Wife (1886); Cuish-ma-Chree (1887); Phyrne (1887); Fin MacCoul (1887); Jimmy Watt (1890); Ninety-Nine (1891. Collaborations, Used Up, with CJ Mathews (1844); Foul Play, with Charles Reade (1868); Foul Play (new. ed. [1890]) [incl. map, folding plate]; Lost at Sea, with HJ Byron (1869), and Bibil and Bijou, with Planché (COVENT GARDEN 29 Aug 1872). ADD, Omoo, or The Sea of Ice (1864).

Micheál Ó hAodha, ‘Dion Boucicault, A note by Micheál Ó hAodha’ [mbr. of Board of Directors], in programme of The Shaughraun, Abbey Th. revival (31 Jan. 1967), with Cyril Cusack (Conn, the Shaughraun, the soul of every fair, the life of every funeral, the first fiddle at all weddings and pattterns’), Desmond Cave (Robert ffolliott, a young Irish gentleman under sentence as a Fenian), Donal McCann (Captain Molineux, a young English officer), Patrick Layde (Fr. Dolan, parish priest of Suil-a-beag), Geoffrey Godlen (Corry Kinchela, a squireen), Peadar Lamb (Harvey Duff, a police agent [informer] in the disguise of a peasant), Edward Golden (Sargeant Jones, of the 41st), Aideen O’Kelly (Claire ffolliott (a sligo lady, sister to Robert), Maire O’Neill (Moya, Fr. Dolan’s niece in love with Conn), Kathleen Barrington (Arte O’Neal, in love with Robert), Harry Brogan et al. (Smugglers), Joan O’Hara (Bridget Madigan and Eileen Lemass (keeners), and Tatters (as ‘Himself’) as well as Niall Buggy, Chris O’Neill, Bernadetta McKenna, Frank Lennon, et al. as peasants, soldiers, constabulary); directed by Hugh Hunt; settings by Alan Barlow; music arranged by Eamon O’Gallagher; Stage manager, Joe Ellis; Scenes, The cottage of Arte O’Neal at Suil-a-beag: sunset; Rathgarron Head; Father Dolan’s cottage: night; A room in Father Dolan’s cottage; Ballyragget House; Father Dolan’s Cottage; Interval; A room in the Barracks; Mrs O’Kelly’s cabin: evening; The prison: night; Rathgarron Head: night; The Ruins of St. Bridget’s Abbey; Outside Mrs O’Kelly’s cabin; Inside Mrs O’Kelly’s cabin; Rathgarron Head: Break of Day; St Bridget’s Abbey.

[ top ]

Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English: The Romantic Period, 1789-1850 (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980), Vol. I; notes that it was W. J. Lawrence who established that Boucicault was the son of Dionysius Lardner, in his article in Ireland Saturday Night (Oct. 28 1922).

Robert Hogan, ed., Dictionary of Irish Literature (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1979), notes that Molin’s bibliography is fairly complete; that many appeared in cheap, ephemeral, and undated copies; that most of his plays were never printed, and that some bibliographical problems will never be solved.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2 selects Boucicault’s version of “The Wearing of the Green”, sung by Shaun the post in Act 1, Sc. IV, [108-09]; Arrah-na-Pogue [234-38]; (err. 1022); 366-67, BIOG, worked for a short time at Guinness’s brewery before emigrating to London to pursue a stage career [...] nominated for a parliamentary seat in Co. Clare and even moved to write a popular nationalist history in 1881 [...] made and lost three fortunes [...] died New York.

Phillis Hartnoll, ed., Oxford Companion to the Theatre (Oxford: Clarendon 1988), notes that London Assurance (1841) was constantly revived, and highly successful for the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1970 thus proving the continuing vitality of the playwright who bridges the gap between earlier Irish writers, Congreve, Farquhar, Goldsmith, Sheridan, to whom Boucicault owed so much, and the later Irishmen Shaw, Wilde, Synge and O’Casey - who all acknowledged their debt to him.

Bibl., London Assurance (1841); Don Cesar de Bazan (1844); Old Heads and Young Hearts (1844); The Corsican Brothers (1852); Louis XI (1855); The Poor of New York (1857), later produced as The Poor [or The Streets] of Liverpool, London, The Streets of Dublin, etc.; Jessie Brown, or The Relief of Lucknow (1858), in which Agnes Robertson appeared; The Octoroon, or Life in Louisiana (1859); Dot, adapt. from Dicken’s The Cricket on the Heart (n.d.); the Colleen Bawn, or the Brides of Garryowen (1860); Arrah-na-Pogue; or the Wicklow Wedding (1864); The Shaughraun (1874); Rip Van Winkle, adapt. from Washington Irving (1865); Hunted Down (1866; originally The Lives of Mary Leigh); The Flying Scud, or Four-Legged Fortune (1866); Babil and Bijou, or The Lost Regalia (1872); Mimi (1772); Belle Lamar (1874).

Oxford Companion to American Literature: Irish-born dramatist and actor, achieved some success with adaptations of French drama, turned to musical interludes and melodramas, and adaptations from Dickens; The Poor of New York, a ‘superficial but graphic picture’ of the panic of 1857; his melodram. about slavery, The Octoroon (1859), from Mayne Reid’s Quadroon, caused a sensation; The Colleen Bawn (1860) inaugurated long series of Irish melodramas which brought his greatest fame; collab. with Joseph Jefferson on Rip Van Winkle (1865); a decade in London, 1862-72, and shorter journeys abroad; declining dramatic career in New York where most of his 132 plays were produced.

Anthony Slide, The Cinema and Ireland (1988), p.17, The Colleen Bawn filmed in 1923 by Stoll, released as a seven-reel feature in May 1924, dir. WP Kellino, with Henry Victor, Stewart Rome, and Marie Ault; and filmed again by Twickenham Studios in 1934 under the title Lily of Killarney, dir. Maurice Elvey, with Stanley Holloway, Dorothy Boyd, John Garrick, and Gina Malo; shot entirely in England apart from prologue views of Killarney.

Hyland Books (1997) lists Charles Reade [&] Dion Boucicault, Foul Play, new ed., [c.1890] with folding map.

[ top ]

Notes

London Assurance (1841): characters incl. Sir Harcourt Courtly, the fossilized Regency beau convinced that he can pay his debts by marrying eighteen-year-old Grace Harkaway; his son Charles, the romantic hero; Lady Gay Spanker, a cigar-smoking foxhunting virago who summons her husband with a dog-whistle while seducing Sir Harcourt; and Dazzle, a raffish character who acts as deus ex machina for the young couple but fails in his own personal designs. (See Grevep Lindop, supra.)

Birthdates: Boucicault gave 1822 as the year of his birth; but Fawkes (op. cit.) gives 27 Dec. 1820, a date arrived at on ‘circumstantial evidence’ but mentions that at least four other dates have been mooted; an estimated $25 million had been paid to see him plays by 1875 (Fawkes, op. cit., p.223, citing Laurence Hutton and Montrose J. Moses, American Dramatist.)

Paternity: Boucicault was the son of Dionysius Lardner [ODNB] and Anne Darley Boursiquot, sister of George Darley [O’hAodha, Theatre in Ireland.]; Lardner’s praternity was established by W. J. Lawrence in his article in Ireland Saturday Night (Oct. 28 1922) [Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, 1980].

Sensation[alism]: The word ‘sensation’ was first applied to Boucicault’s Colleen Bawn among all stage-productions. (See Jean Ruer, ‘Plaidoyer pour la Litterature à Sensation’, in Bulletin de la Faculté des Lettres de Strasbourg, 47th year, No. 4 (Jan. 1969).

Boer War: Benefit Performance of Colleen Bawn, for ‘benefit of families of Irish soldiers killed in South Africa’ (Theatre Royal, Dublin; 14 Dec. 1899), before Lord Lieutenant Cadogan and Countess Cadogan.; also The Corsican Brothers, with Martin Harvey, supported by his London Company (Theatre Royal, Dublin; 5 Nov. 1906).

Oscar Wilde: Boucicault’s widow was a recipient of tickets sent by Oscar Wilde in 1883. See Ian Small, Oscar Wilde Revalued: An Essay on New Materials and Methods of Research (Greensboro N. Carolina, ELT Press; Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1993), p.35.

Namesake: Joshua Edkins, A collection of Poems by Different Hands (Dublin 1801) contains work by William Drennan, Fighting Fitzgerald et al., incl. also W. O’Brien Lardner.

Gerald Griffin: Griffith was the creator of the original Myles as a character in The Collegians (1829), Chap. 7: ‘“Myles Murphy! Myles-na-coppuleen? - Myles of the ponies, is it?” said Lowry Looby, who just then led Kyrle Daly’s horse to the door. “Is he in these parts now?” / “Do you know Myles, eroo?” was the truly Irish reply. / “Know Myles-na-coppuleen? Wisha, an’ ‘tis I that do, an’ that well! O murther, an’ are them poor Myles’s ponies I see in the pound over? Poor boy! I declare it I’m sorry for his trouble.” / “If you be as you say,” the old innkeeper muttered with a distrustful smile, “put a hand in your pocket an’ give me four and eightpence. an’ you may take the fourteen of em ’after him.” (See full text of The Collegians in RICORSO > Library > “Irish Literary Classics” - as attached.)

[ top ]