Life

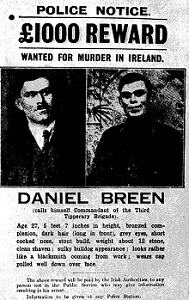

| 1894-1969; b. 11 Aug., 1894, Donohill, Co. Tipperary; joined the IRB in 1912 and the Irish Volunteers 1914; participated with Seán Tracy and Sean Hogan in the ambush at Soloheadbeg, nr. Monard, Co. Tipperary, 21 Jan. 1919 - being the opening day of Dail Eireann - in which attack Tracy fired the revolver rounds that killed two RIC-men (Constables McDonell and O’Connell) escorting a load of dynamite, thus initiating the Anglo-Irish War, 1919-21; Breen led the 3rd Tipperary Brigade of IRA, attracting an award of £1,000 for his arrest; rescued Seán Hogan - who was captured by the RIC while visiting a girl-friend - from guarded train at Knocklong Station, and later shot himself free from a house in Drumcondra with Tracy, though badly wounded; cross St Patrick Training College and the Tolka, and sought refuge in an unknown house before collapsing; |

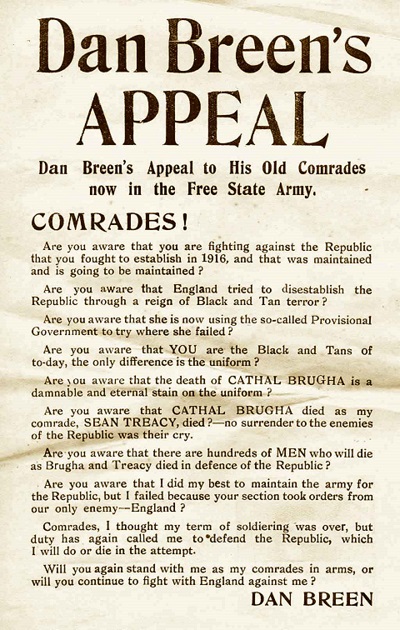

| travelled went to America but returned on request of Liam Lynch to counter the Treaty; called for former Volunteers to resist the Treaty, 1922 [‘I would never have handled a gun or fired a shot ... to obtain this Treaty’]; arrested and held in Limerick Gaol and then transferred to Mountjoy Prison in Dublin; endured 12 days of hunger-strike and was elected TD for Tipperary while in prison, 1923; member of Clann Éireann and anti-Treaty deputy, Jan. 1927, being the first Republican to take the Oath of Allegiance; spent some years in Chicago [USA], where he managed a speak-easy and is thought to have come into conflict with Al Capone; elected Tipperary TD, 1932-65 - during which he was noted for his finger-snapping method of attracting the attention of the Ceann Comhairle; promoted early film industry in Ireland as TD; |

| his record of guerrilla war, My Fight for Irish Freedom (1924), was brought to print with much assistance from Katherine O’Doherty (wife of Seumas O’Doherty) to whom he refused to pay the agreed sum of £20 due to her as ghost-writer in spite of the book’s success; disparaged the role of Seamus Robinson in the actions of the Tipperary 3rd Brigade; a later edition deletes the admission that the Soloheadbeg attack had been intended to break the stale-mate, openly stated in the first and reiterated in subsequent interviews; Breen was a pall-bearer at the funeral of Hermann Gortz in 1947, and he displayed pictures of Hitler prominently in his house until 1948; commended his enemies in the Civil War and called for reconciliation with the Northern Ulstermen in Dáil farewell speech, 1961; spoke out against the Vietnam War; gave RT&E interview to Jack White, 1967; d. 27 Dec. 1969; 10,000 people attended his funeral at Donohill, Co. Tipperary; an RTE documentary called ‘Dan Breen Remembered’, with Pádraig O‘Neill reporting, was broadcast on 30 Dec. 1969. DIB DIH |

|

|

Works

My Fight for Irish Freedom, [intro. by Joseph McGarrity] (Dublin: Talbot 1924; + 3 imps.), xii, 258pp. [cover bears imbossed title “Dan Breen’s Book’ in faint green cloth in circle-frame with rays extending to the edge; Do. [2nd edn.] with an introduction by Joseph McGarrity (Dublin: Talbot Press 1924), xii, 258pp., 12 pls.; Do. (Dublin: Anvil Books 1964, 1974), 192pp.; and Do. [new edn.], incl. letter to Dan Breen from G. Bernard Shaw and introduction by the editor of Anvil Books (Dublin: Anvil Books 1981), 208pp., 16 pls.; also Do., in an Irish trans. by Séamas Daltún as Ag troid ar son na saoirse (Tralee: Anvil 1964).

[ top ]

Criticism

Joseph [Joe] G. Ambrose, The Dan Breen Story (Cork: Mercier 1981), 119pp., and Do. [rev. edn.], as Dan Breen and the IRA (Cork: Mercier 2006), 224pp., ill. [8pp. photos]; also Oliver Snoddy, ‘Notes on Literature in Irish Dealing with the Fight for Freedom’, in Éire-Ireland, 3, 2 (Summer 1968), pp. 138-48.

[ top ]

Commentary

Denis Ireland (From an Irish Shore, 1939), is ‘still wondering if Mr. Breen wrote it [My Fight] himself’ [145]; gives long account with quotations from Dan Breen’s My Fight for Irish Freedom; called the narrative ‘something Homeric in the full sense of that overworked epithet’ [146]; his ‘escape from the house in Drumcondra one of the most extraordinary incidents of the Black and Tan War in Ireland.’ [152].

St. John Ervine, Craigavon (1949), calls My Fight for Irish Freedom ‘a work writen in the worst style of journalistic clap-trap’, citing Michael Collins’s repudiation of the Soloheadbeg in the Dáil (p.336).

Peter Costello, The Heart Grown Brutal: The Irish Revolution in Literature from Parnell to the Death of W. B. Yeats, 1891-1939 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1977), quotes Charles Townsend to the effect that there can be no doubt from the account written by Sean Tracy’s companion-in-arms Dan Breen that the attack at Soloheadbeg that the attack was a self-conscious assertion of the ‘physical force’ wing. (Townsend, The British Campaign in Ireland, 1919-21, Oxford 1975, p.16, citing Breen, 1924, new edn. 1964, p.38; Costello, op. cit., p.117.)

Robert Kee, The Green Flag (1972), writes: ‘When Ernie O’Malley captured three British Officers and felt obliged to execute them in the period of retaliations, Summer 1921, Dan Breen finished them off with revolver shots as they lay twitching on the ground.’ (pp.707-08, citing O’Malley, On Another Man’s Wounds, pp.328-32.)

Brian Inglis, Downstart: Autobiography of Brian Inglis (London: Chatto & Windus 1990): ‘When West Briton [his earlier autobiographical work] was published in 1962, I had another indication of the way things were changing in Ireland, in the form of a letter from Dan Breen. In 1919 Breen had led a group of Volunteers in Tipperary in the ambush which triggered off the War of Independence; “one of the great berserkers of the war”, Tim. Pat Coogan had described him in Ireland since the Rising, who had eventually become “in many ways the most colourful figure in the Dail”. I had thought Breen an incorrigible Republican hardliner, but in his farewell speech to the Dail in 1961 he had included tributes to some of the men he had fought against in the Civil War, and had actually urged reconciliation with the Ulster Orangemen, in place of the anti-Partition campaign. Now, “You will I know be surprised” he wrote, “to get a letter from me. Your grandmother would not like it - in fact she may now turn in her grave at you reading it. I only want to congratulate you on your book “West Briton”. You surely got to grips with the real position. It’s sad for Ireland to lose men like you - you are needed back here to build up an Ireland not rich, but with a culture.” The handwriting was at times barely legible; he had been ill for some time, he explained, and found it hard to write, “so excuse my effort”. As I wrote back to tell him, I could think of no letter which had given me more pleasure.’ (p.273.)

Benedict Kiely, Drink to the Bird (London: Methuen 1991): ‘[My Fight for Irish Freedom] was, about that time, almost compulsory Irish nationalist reading. But even though Dan Breen had to be accepted as a Tipperary hero battling in the 1920s against the pretty atrocious Black-and-Tans, my sophisticated secondary-school taste did not give a high rating to his book, not for political but for literary reasons. Don’t remember now, if I ever did know, whether Dan Breen wrote the book himself or had somebody do it for him. But it was a crude enough story and not too well told. / M. J.’s [Kiely’s school-teacher] objections were more and other than literary. He held it no heroic thing to hide behind a hedge and shoot men in the back. His was an outdated standard of behaviour even then and one that would have imposed an over-rigorous discipline on the devoted guerrilla. Yet when, in later years, I met Dan Breen and found him to be a charming, humorous and human man, it occurred to me, from the hints I gathered from his talk, that his standards did not much differ from those of M. J. Curry. Deeds done in the heat of youth, and not only deeds of blood, seem different to the backward view of age. Naturally I did not raise the delicate topic with Dan Breen, to whom I was introduced by a celebrated Capuchin friar. But in the conversation that followed our introduction, he spoke broodingly of bad times and of things then done [146] that in the time and place he was talking in (Dublin in the late 1940s) would be difficult to justify. He was not speaking only of or for himself. / We have lived, some of us, to see better times and more abominable deeds.’ (pp.145-46; and note: Kiely goes on to explain the inspiration for his own novel Proxopera - see longer extract, infra.)

Roy Foster, Paddy and Mr Punch (1993), remarks that Breen’s admission to having detonated the Anglo-Irish war was inspired by suspicions that the Sinn Féin politicians were going to adopt a constitutional rather than a ‘physical force’ approach; this admission was deleted in the second edn. and edns. thereafter. (Foster, p.97.)

Jer O’Leary, letter in History Ireland (Winter 1997), claims that the ambush of a party of the RIC by men of ‘D’ Company of the Volunteers resulted in the capture of two magazine Lee-Metfor carbines and two slings of .303 ammunition with 50 rounds occurring nr. Beala Ghleanna, between Ballyvourney and Balingary in West Cork on 8 July 1918, six months before Soloheadbeg. (p.11.)

[ top ]

Quotations

God of mercy: ‘They talk about a God of mercy. No God of mercy could allow the pain I’m suffering now.’ (Reputedly said in interview on RTÉ when he was dying of cancer; quoted in Pearse Hutchinson, contrib. to Dermot Bolger, ed., short contrib. to Letters from the New Island: 16 on 16, 1988, p.14.)

Breen reputedly said on RTÉ television, ‘We got our freedom too late - we should have got it in 1798’ - and expressed no regrets for Soloheadbeg on the grounds that he would ‘do it again’ if his country were invaded. (Quoted by Pearse Hutchinson [no ref.] in ‘A Beautiful Thing Wronged’, Scotland and the Easter Rising: Fresh Perspectives on 1916, ed. Kirsty Lusk & Willy Maley, [Scotland:] Luath Press 2016) - available online; accessed 22.01.2022.)

| On Soloheadbeg |

|

| Quoted in Remembering Seán Tracy, in

‘Come Here To Me!’, Dublin Life & Culture (17 Aug. 2019) - online; posted by Basil Miller on Facebook, 17.08.2019. |

|

[ top ]

Notes

Dorothy Macardle the historian Macardle offers an account of Soloheadbeg in Irish Republic with remarks on Breen which De Valera called ‘an exhaustive chronicle of fact’.

Seumas [var. Séamus] Robinson: Robinson was Officer Commanding the Tipperary 3rd Brigade at the time of the Soloheadbeg attack but was apparently unaware of it until news of the dead policemen emerged. His role as O/C was treated by Breen and Tracy as incidental insofar as they claimed to have selected him for a nominal role only rather than take the position themselves. Much of the commentary on the event turns on the question of his slighted seniority and his real abilities which were proven in prison when he refused repeatedly to cooperate with the British authorities. According to Joe Gannon: ‘Breen and Robinson had a very contentious post-war relationship and far different memories of many aspects of the period. The planning of Soloheadbeg was one of them, and since Treacy didn’t survive the war, and the teenage Hogan was never a leader of their actions, there was no one left to say where the truth might lie. Breen’s story was that he and Treacy planned the ambush and that Treacy had gotten Robinson installed as commander of the 3rd Brigade because he would be an easily manipulated stooge. Robinson’s version was that Treacy had discussed the action with him in December, asking his permission to do it, which he had granted. Whichever of those different versions was correct, there was no question [viz., no doubt] that none of them had asked permission from their superiors in the Volunteers.’ Robinson acted as best man at Breen’s wedding but the publication of My Fight for Irish Freedom (1924), in which Breen played down Robinson’s role so conspicuously, irreparably damaged their friendship. (Joe Gannon, ‘Tipperary’s Dan Breen: The Hardest Hard Man’, at Wild Geese - online; accessed 13.08.2021.

Error record: Ricorso previously cited on this page a quotation from Frank O’Connor, An Only Child (1961) in which he writes ‘I did not like Breen. [...]’ (Chap. 15; pp.192-93; rep. in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, gen. ed. Seamus Deane, Derry: Field Day 1991, Vol. 3.) This was actually a reference to the school-teacher Denis Breen and not Dan Breen as previously suggested here. I have been corrected in this matter by Brendan Lyons, following his contact with RICORSO. He further remarks that Denis Breen was a friend of Daniel Corkery [q.v.]. (15.04.2022.)

[ top ]