] Life

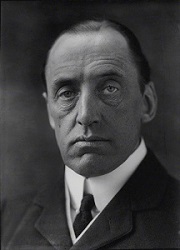

| 1854-1935; b. 4 Harcourt St., Dublin, 9 Feb. 1854 [Edward Henry; afterwards Right Hon. Sir Edward Carson; Lord Carson of Duncairn, Baron Carson]; bapt. at St. Peter’s, Aungier St. at five weeks; 2nd son of namesake, an architect (himself the son of Wm. Carson of Dumfriesshire, chip and straw merchant); Edward Carson Snr. m. Isabella Lambert, dg. of Peter and Eleanor [née Seymour] of Ballymore Castle - making Carson a cousin to the Lamberts of Castle Ellen, Co. Galway where he visited in boyhood and first fell in love with his cousin Katie (who married a soldier); ed. Arlington House (Portarlington School) and TCD, (Classics, BA), 1871-75 [var. 76]; shared membership of Hist. with Bram Stoker [Auditor] and Oscar Wilde whose claims of college friendship he later denied; entered on an Exhibition Scholarship and works for Foundation Schol. in same year as Wilde, but fails to get elected; joined Irish bar, Easter 1877; m. Annette Kirwan [with whom 4 children, d 1913; dg. of an RIC County Inspector], 19 Dec 1879 - without approval of his father who witheld further support; appt. crown counsel by Sir Michael Hicks Beach, Salisbury’s chief secretary prior to arrival of Balfour as chief sec. in 1887; appt. solicitor-gen. for Ireland, 1892, enjoying the patronage of Lord Londonderry; served as MP for Dublin University, 1892-1918 - a seat he held in three successive terms, with D. R. Plunket, W. E. H. Lecky, and J. H. M. Campbell as the second member for the University in each; joined the English bar, 1893; moved to take Marquess of Queensberry’s brief against Oscar Wilde on hearing of exploitation of boys, and destroyed Wilde in cross-examination, 1895; appt. solicitor-general for England [Conservative & Unionist], 7 May 1900, remaining in office until 1905; knighted, 1900; |

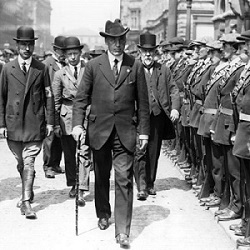

| declared in a university debate of 1907-08 that he would not send a son to TCD if it lost its ‘Protestant atmosphere’; defended Evening Standard in libel case brought by Cadburys, related to their supposed knowledge of slavery in Sao Tomé, 1908; elected leader of Irish Unionist Council, 1910; won the Winslow Boy case concerning unjust expulsion of young Archer-Shee from Naval Academy, 1910; encouraged Ulstermen to resist Home Rule; greeted a demonstration of 50,000 unionists who marched from Belfast centre to Craigavon, to be addressed by him: ‘I now enter a compact with you and every one of you [to] defeat the most nefarious conspiracy that has ever been hatched against a free people’, 23 Sept. 1911; Third Home Rule Bill introduced, Westminster, 11 April 1912; with others, formed the Ulster Volunteer Force [UVF], 1912; following Thomas Agar-Robertes’ (Lib.) amendment to the Irish Home Rule Bill to exclude Armagh, Derry, and Down - sometimes said to have been instigated by Carson with Andrew Bonar Law - proposed his own amendment to exclude the nine Ulster counties; led 237,638 Ulster Unionists [var. 471,414 incl. women] in signing of Solemn League and Covenant not to accept Home Rule government, 28 Sept. 1912; became involved in Ulster Volunteer gun-running, 1913, with Sir George Bull as his London contact; m. Ruby Frewen [aetat. 19; dg. Lt.-Col. Stephen Frewen of Yorkshire], Sept. 1913; told Ulster Covenanters: ‘Don’t be afraid of illegalities’; Bonar Law moves a vote of censure against government deployment of troops and navy, 19 March 1914, with support of Carson (‘Let the government come and try conclusions with us in Ulster [...] Ulster is on the beset terms with the Army’); appt. British attorney-gen. 1914; resigned 1915; |

| Carson was assured by Lloyd George that the 6 Counties would be permanently excluded from Home Rule, April 1916; appt. first lord of admiralty in War Cabinet, 1917; resigned from Cabinet over War strategies of David Lloyd George, Jan. 1918; elected MP for Duncairn, Belfast, 1918; wrote Ireland Under Home Rule (1919); recommended setting up the State of Northern Ireland to Unionists (‘Ulster will be a geographical fact’); the Fourth Home Rule Bill, introduced on 25 Feb. 1920, aimed to exclude Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone from an Irish Republic [Free State]; Home Rule Bill passed into law with the granting of Royal Assent, 23 Dec. 1920; Carson resigned his leadership of Unionist Party in order to take office as Lord of Appeal, 1921; purchased Cleve Court, an Queen Anne house nr. Minster in the Isle of Thanet, Kent; created Baron Carson of Duncairn [Lord Carson of Duncairn], a life peerage; d. 22 Oct. 1935, at his home in Kent; bur. St. Ann’s Cathedral, Belfast; a larger than life-size statue by L. S. Merrifield stands at Stormont, Northern Ireland - dedicated ‘in love and gratitude‘ by ‘the loyalists of Ulster’, unveiled in his presence, July 1932, on his last visit to N. Ireland; not commemorated at his alma mater, Trinity College, Dublin; Edward Majoribanks, who publ. the first volume of an official biography (Vol. 1) committed suicide in 1932; the work was then completed by Ian Colvin (Vols. 2 & 3 1936); Carson’s his personal effects purchased at auction by Ian Paisley in the 1970s (Belfast). ODNB DIB DIH OCIL FDA |

|

|

|

|

[ top ]

Works

|

Criticism

|

See George Dangerfield, ‘The Guns of Larne’ [chap.], in The Strange Death of Liberal England (London: Constable 1932; rev. edn. 1970), and Ronan Fanning, Fatal Path: British Government and Irish Revolution, 1910-1922 (London: Faber & Faber 2013). |

See also Finbarr O’Regan, The Lamberts of Athenry: A Book on the Lambert families of Castle Lambert and Castle Ellen, Co. Galway : a study of the townland associated with them and their Edward Carson connection (Athenry: Finbarr O’Regan 1999), 254pp., ill.p |

Bibliographical details

Geoffrey Lewis, Edward Carson: The Man Who Divided Ireland (London: Bloomsbury 2006), 288pp. CONTENTS: Introduction; 1. Dublin; 2. Home Rule; 3. London; 4. Oscar Wilde; 5. The End of Unionist Government; 6. The Naval Cadet; 7. The House of Lords; 8. The Conservative Leadership; 9. Asquith’s Home Rule Bill; 10. Ulster; 11. Marconi; 12. The Curragh; 13. Craigavon; 14. War and Peace. 15. Opposition; 16. The Fall of Asquith; 17. Final Attempt. Notes; Bibliography; Index. [Billed as 1st edn. at Bloomsbury but note review by Frank Callanan, in The Irish Times (15 June 2005), as infra - and listed there as Hambledon Continuum 2005].

[ top ]

Commentary|

George Bernard Shaw Mary C. Bromage M. J. MacManus A.T.Q. Stewart |

Joseph Lee Frank Callanan Foster & Jackson |

George Bernard Shaw (on Irish Partition): ‘England has gone too far this time. She has done what I thought impossible. She has rallied me to the side of Ulster. Now I suppose I shall be shot; but I cannot help that. Am I not a Protestant to the very marrow of my bonoes? Is not Carson my fellow townsman? Are not the men of Ulster my countrymen?’ [236; …] ‘And yet, could Sir Edward Carson and Lord Birkenhead have been put more completely in the cart if the British Government had made Ireland a present to the PopeP What is Ulster to do with her self-determination? One-eyed people are full of surmises as to what the southern Parliament will do, prophesying, with assumed confidence, that it will declare the Republic. Nobody thinks of poor Ulster, who is in a far more difficult position. For the first act of her Parliament must be to re-unite her with England. That goes without saying. But the difficulty will begin earlier. Can she consistently elect a separate Ulster Parliament at all? Is she not bound by all her vows and covenants to boycott this abomination of a Home Rule Parliament: nay, of two Home Rule Parliaments? And yet if she does, Labor will jump the claim. Is it any wonder that Sir Edward Carson sat glum and refused to give any assurances to the perfidious Welshman [Lord Birkenhead] who, with an air of solving the problem for him, was putting him into the worst hole of his career?’ (Letter to The Irish Statesman, 10 Jan. 1920; rep. in The Matter with Ireland, ed. David Greene & Dan Laurence, Constable, 1962, pp.236-40; pp.236, 239.)

Mary C. Bromage, Eamon de Valera and the March of a Nation (NY: Noonday Press 1956): ‘Up in Belfast only a few hours’ train trip north of Dublin, the advocacy of home rule by a young Englishman connected with the British government, Winston S. Churchill, sounded daring. His own father, Lord Randolph Churchill, had preached the very {34} opposite of home rule, declaring, "Ulster will fight, Ulster will be right," and this remained the motto of Edward Carson, chief among those resisting home rule. The possibility that the North and South of Ireland would be partitioned over the matter of loyalty to the Crown arose by 1912. The Orangemen of the North would sooner part company from the rest of Ireland than from the monarch, and Carson was organizing a force called the Ulster Volunteers to defend union. In this he had the expert advice of an Irishman high up in the British Army, Sir Henry Wilson.’ (pp.34-35.) Further: ‘The Northerners being mustered by Carson in Belfast constituted a focus of belligerent unionism. They were determined to separate themselves if the British Government, in response to the programme of the Irish Party, should move in the direction of home rule for all of Ireland. / England was not so much occupied with this problem as with watching the crisis developing on the continent. [...]

M. J. MacManus, ‘The Last Stage Irishman’, in Adventures of an Irish Bookman [ed. by Francis MacManus] (Dublin: Talbot Press 1952), pp.112-16, being an account of St. John Ervine’s biography of Carson in which Ervine appears to advance the theory that Ulster choose Carson because he was the last stage-Irishman: ‘[…] the starry hero of all the politest young ladies of Belfast, has not done anything to promote the well-being of Ireland, never has done anything, and never will.’ Further: ‘Sir Edward Carson is a stage Irishman […] Sir Edward Carson is the last of the Broths of a Boy. He has a touch of Samuel Lover’s Handy Andy in him. He is the most notable of the small band of Bedadderers and Bejabberers left in the world; the final Comic Irishman, leaping on to the music-hall stage or the political platform, twirling a blackthorn stick and shouting at the top of a thick, broguey voice (carefully preserved and cultivated for the benefit of English audiences) ... “bedad and bejabers and begorra, is there e’er a man in all the town dare tread on the tail of me coat, bedad, bejabers and begorra!” (p.115.) ‘I would have said more [Ervine pleads] if there had been more to say.’ (p.116.). See also ‘The Playboy of the Irish Literary Revival’ [on George Moore] and ref. to ‘Mr St John Ervine’s rollicking Sir Edward Carson’ (ibid., p.122; see further under Ervine, infra.)

[ top ]

A.T.Q. Stewart, Edward Carson [Gill Irish Lives] (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1981): Carson called the Home Rule Bill ‘the most nefarious conspiracy that has ever been hatched against a free people we must be prepared … the morning Home Rule passes ourselves to become responsible for the government of the Protestant Province of Ulster.’ (Craigavon meeting, 23 Sept. 1911). [73] Ulster Day, 28 Sept., 1912, 237,368 men signed Ulster Covenant, based on Scottish Covenant of 1775, and 234,046 women signed a similar ‘declaration’. [78] A. T. Q. Stewart corrects misconceptions about gun-running, Larne, 24,600 of which 20,000 German, April 1914. [ftn, 84.] Carson, relinquishing leadership of the Ulster Unionist Council, 4 Feb. 1921, ‘For the outset let us see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from Protestant majority. let us take care to win all that is best among those who have been opposed to us in the past. While maintaining intact our own religion let us give the same rights to the religion of our neighbours.’ (Hyde, 449) [120] Expressing sense of betrayal in House of Lords, in his maiden speech, following the Anglo-Irish treaty, 1921, he aspersed Chamberlain, Birkenhead (W. E. Smith), Curzon, et al., ‘I was in earnest. What a fool I was! I was only a puppet, and so was Ulster, and so was Ireland, in the political game that was to get the Conservative Party into power…. I could not help thinking that it was very like, after having shot a man in the back, going over to him and patting him on the shoulder, and saying, ‘Old man, die as quickly as you can, and do not make any noise … Why all this attack made on Ulster? What has Ulster done? I will tell you. She has stuck too well to you, and you believe because she is loyal you can kick her as you like.’ (Hyde, 446) [126] [Cont.]

A.T.Q. Stewart (Edward Carson, 1981) - Bibl.: The official biography, Edward Majoribanks[1 vol.] & Ian Colvin [2 vols.] (3 vols., 1932-36); H. Montgomery Hyde, Edward Carson (1953; rep. 1979) [more accurate]. See J. C. Beckett, ‘Carson - Unionist and Rebel’, in F. X. Martin, Leaders and Men of the Easter Rising: Dublin 1916 (London 1967), rep. in Beckett, Confrontations, Studies in Irish History (London 1972); R. B. McDowell, ‘Edward Carson’, in Conor Cruise O’Brien, ed., The Shaping of Modern Ireland (London 1960). Contemp. memoirs incl. F. E. Smith, Lord Birkenhead, Contemporary Personalities (London 1924); Sir Thomas Comyn-Platt, ‘The Ulster Leader’, in National Review (Oct. 1913); Thom. Moles, Lord Carson of Duncairn, with foreword by Sir James Craig (Belfast 1925); Sir Douglas Savory, ‘Lord Carson’, in ODNB. Also Patrick Buckland, Irish Unionism I, The Anglo-Irish and the New Ireland 1885-1922 (Dublin 1972), II, Ulster Unionism and the Origins of Northern Ireland 1886-1922 (Dublin 1973), and Irish Unionism 1885-1923, A Documentary History (Belfast 1973).

Bibliography [commentary & sources] incls. John N. Biggs-Davison, George Wyndham (London 1951); Wilfrid S. Blunt, The Land War in Ireland (London 1912); Frederick H. Crawford, Guns for Ulster (Belfast 1947); F. P. Crozier, Impressions and Recollections (London 1930); St John Ervine, Craigavon, Ulsterman (London 1949); Daniel Farson, The Man who Wrote ‘Dracula’ (London 1975); Sir James Ferguson, The Curragh Incident (London 1964); Denis Gwynn, Life of John Redmond (London 1932); Thomas Jones, Whitehall Diary, Vol. III, ‘Ireland 1918-1925’, ed. Keith Middlemas (London 1971); Ronald McNeill, Ulster’s Stand for Union (London 1922); Lord Peter O’Brien, Reminiscences (London 1916) [‘called Peter the Packer’]; A. P. Ryan, Mutiny at the Curragh (London 1956); A. T. Q. Stewart, The Ulster Crisis (London 1967; rep. 1979).

[ top ]

Joseph Lee, Ireland 1912-1985 (Cambridge 1989); Sir Edward Carson, a Dubliner rather than an Ulster Scot, elected Unionist leader in Feb. 1910, was a ‘sombre, melanchol[ic] man, a man of notable courage and forensic ability, he brought the Orange cause a considerable capacity for organisation, a moral fervour almost fanatical in its intensity and an instinctive feel for high, political drama.’ [5] Further, Carson shared in the widespread illusion that the south of Ireland could not survive without the industrial north. At a monster meeting at Craigavon in Sept. 1911, he told the crowd that ‘we must be prepared the morning Home rule passes, ourselves to become responsible for the government of the Protestant province of Ulster’; ‘… Carson told his Ulster Protestant audience of 200,000 at Balmoral in April 1912 that ‘the government by their Parliament Act has erected a boom against you, a boom to shut you off from the help of the British people.’ [13] Carson resigned Feb. 1921; James Craig abandons political career in London to succeed him. By mid 1922 there was one armed policeman to every two Catholic families in Ulster. [59-60] Bibl., A. T. Q. Stewart, The Ulster Crisis (London 1969); Stewart, Sir Edward Carson (Dublin 1981) See also Joseph Lee, Ireland 1912-1985, Politics and Society (Carmbridge 1989).

David Stevens, ‘Religious Ireland (II)’, in Edna Longley, ed., Culture in Ireland, Diversity or Division [Proceedings of the Cultures of Ireland Group Conference] (QUB: Inst. of Irish Studies 1991), quotes Carson’s maiden speech in House of Lords, calling it ‘a bitter threnody, and requiem for an Irish Unionists tradition’, ‘I speak - I can hardly speak - for all those relying on British honour and British justice, who have in giving their best to the service of the State seem themselves now deserted and cast aside without one single line of recollection or recognition in the whole of what you call peace terms in Ireland.’ [quoted from HM Hyde, Life of Carson, Heinemann, 1953, n.p.] Stevens remarks: ‘Carson’s tragedy was that he was not an Ulster Unionist but an Irish Unionist; and I think he must have been speaking for many.’ (p.145).

Frank Callanan, review of Geoffrey Lewis, Edward Carson: The Man Who Divided Ireland, in The Irish Times (15 June 2005), Weekend, p.10: ‘[…] Carson was bereft of political imagination or reflectiveness. This served him well in his history role if it makes a somewhat forbidding subject for a political biography. He saw himself as a patriotic conscript rather than a politician, obliged in a time of peril to forsakehis professional life to defend the existing constitutional order. His modus operandi was that of a barrister brutally wresting and imposing a settlement. […; &c.]’ (Copied by hand at date; available online - accessed 17.07.2021; see full copy in RICORSO Library > Criticism > Reviews - as attached.)

Roy Foster & Alvin Jackson, ‘Men for All Seasons? Carson, Parnell, and the Limits of Heroism in Modern Ireland’, in European History Quarterly, 39, 3 (2009): ‘Charles Stewart Parnell and Edward Carson both failed in their fundamental political objectives (a socially and geographically united and autonomous Ireland, as against a wholly Unionist Ireland). However, both men were the objects of great reverence during their lifetimes; and each was the focus of careful image building. Their heroic reputations were swiftly defined in regal, mystical and sexual terms: the reputation of each was commodified. / Both were redefined according the needs of later generations: Parnell’s alleged radicalism grew with the passing of the years, and with the establishment of an independent Ireland under bourgeois Catholic domination; the complexities of Carson’s career were masked by the demands of later Unionist generations. Both men have to some extent been superseded by rival heroic reputations within their respective cultures. Parnell’s standing has been challenged by the insurgents of 1916-21, while Carson’s legacy has been sometimes overshadowed by that of his former lieutenant, James Craig.’ (p.414.)

[ top ]

On Covenants & the Union—

| See Allan Blackstock & Frank O’Gorman, eds., Loyalism and the Formation of the British World, 1775-1914 (Woodbridge, Suffolk, Boydell Press 2014) - Introduction: |

‘Loyalism’s role in the amalgamation of a Scottish identity with a larger British identity is undoubted, but it came haltingly. Historically, although the Scottish and English crowns were unified in 160s, no British state existed in the Sixteenth century. England remained a composite (not a unitary) state, and the 1603 union was scarcely a political one. Indeed, to conceive the assertion of a British imperium over Scotland as an alien imposition really ignores reality. A linguistically and culturally united Scottish nation never existed as most Scottish people spoke English. A different kind of Britishness derived from the Scottish church’s [7] Calvinism which promoted a supra-national way of thinking. This model became compelling after 1603 and found numerous advocates, not least James himself. The Solemn Leage and Covenant between England and Scotland in 1643 was interpreted by some Scots as a sort of sacrilised confederation. However, by the later seventeenth century the term “Britain” began to depict the Anglo-Scottish state represented by the monarch. Britannia started to appear on coins and medals in 166 and there was increasing acceptance of “British” in descriptions of the army and the navy. Even before 1688, the idea of a unique British constitution, accessible to all and exhibiting a unique historical and even moral dynamic was commonly circulated. |

| See also Sharon Adams & Julian Goodare, eds., ‘Scotland and its Seventeenth-Century Revolutions’ [being Chap. 1 of], Scotland in the Age of Two Revolutions, ed. Adams & Goodare (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press 2014). |

‘[...] The Covenanters, in fact, left a long-lasting radical tradition. The Galloway Levellers, in 1724, organised popular resistance to agriculture enclosures, agitating and destroying dykes. On several occasions when groups of Levellers were challenged by the Riot Act, they responded by reading the Solemn League and Covenant. [...; here the authors write further of] radical demands for parliamentary reform. This perhaps brought these radicals closer to the political traditions of the 1630s nd the 1640s and the revolutionaries of 1689 than the establishment-minded presbyterian martyrology that became popular through the works of Robert Wodrow and his successors. |

[ top ]

References

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2; all contemporary Irish leaders defeated in their aims, 209; Unionist proclaim readiness to resist Home rule and if necessary to set up their own government; Eoin MacNeill’s lesson drawn from it, in The North Began (1913), 285-288 [passim]; Smith acting as prosecution at the Casement trial reminiscent of Carson at Wilde’s; Smith was Carson’s aide-de-camp in the UVF [Seamus Deane, ed.], 295; (499); Hart, a character in Ervine’s Mixed Marriage (1911), probably modelled on Carson, 713n. Also, Windham Thomas Wyndam-Quin seconded Lord Morley’s motion supporting the Articles of Agreement with the Free State in 1921, and was addressed thus by Carson, ‘The seconder of the Address is a brother Irishman. I have known him for many years. His one great characteristic has always been that he never could agree with anybody on any subject, and I cannot but congratulate him that this evening he has at last found peace and understanding in the knowledge that he will be under that perfect Government which will be evolved out of the murder gang in Ireland. I wish him every success and every happiness in the future of his country and his own life there.’ (14 Dec. 1921).

[ top ]

Quotations| Carson and the the Land League Boycott |

| ‘Do you know what a boycott in Ireland means? Sir Edward Carson was to ask a half-incredulous public meeting in England. Do you know that a mother cannot get milk for her dying babe; and that it will be allowed to die, simply, forsooth, because the father or mother is under a boycott? ... It is a state of savagery.’ (Quoted in Edward Grierson, ’John Bull’s Other Island’, The Imperial Dream: British Commonwealth and Empire 1775-1969 (Newton Abbot: Victorian (and Modern) Book Club 1973) [Chap. 13], p.190.) |

Resistance: ‘What I am anxious about is to satisfy myself that the people really mean to resist. I am not for a mere game of bluff and unless men are prepared to make great sacrifices which they clearly understand the talk of resistance is no use.’ (Letter to James Craig, 29 July 1911, quoted in Ervine, Craigavon: Ulsterman, 1949, p.185; cited in Calton Younger, A State Divided, 1972, p.165.)

Warning: ‘We tell you this - that if, having offered you help, you are yourselves unable to protect us from the machinations of Sinn Féin, and you won’t take our help, well then we will tell you that we will take the matter into our own hands.’ (12 July 1920; quoted in Alan Parkinson, Belfast’s Unholy War: The Troubles of the 1920s (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2004; cited by John Kirkaldy, in review of same, Books Ireland, March 2005, p.54.)

United Ireland?: ‘There is no one in the world who would be more pleased to see an absolute unity in Ireland than I would, and it could be purchased tomorrow, at what does not seem to me a very big price. If the South and West of Ireland came forward tomorrow to Ulster and said - “Look here, we have to run our old island, and we have to run her together, and we will give up all this everlasting teaching of hatred of England, and we will shake hands with you, and you and we together, within the Empire, doing our best for ourselves and the United Kingdom, and for all His Majesty’s Dominion will join together”, I will undertake that we would accept the handshak’.

Speech in Torquay, 30 January 1921

[ top ]

Notes

Harcourt St.: During the attempt to save Carson’s house on Harcourt St., in 1993 [as reported in the Irish Times], Ian Paisley submitted the view that plans to demolish it revealed a total misunderstanding which the Dublin authorities had towards Northern Ireland. Ireland was one country when Carson was born: ‘He was adamant that he was an Irishman and while he led the Ulster Unionists he always maintained that he was an Irish Unionist […] Great men in the country of their birth are honoured in history not only by those who agreed with their political and religious ideals but all who have interest in the heritage of history’.

[ top ]

A Chronology of Home Rule| 1886 - First Irish Home Rule Bill; introduced by Gladstone and defeated in the House of Commons, resulting in the fall of his Liberal government. |

| 1893 - Second Irish Home Rule Bill passed the House of Commons, but defeated in the House of Lords under its power of veto (substituted by a power of delay in the Parliament Act of 1911). |

| 1909 - Lloyd George presents the ‘People’s Budget’ involving wealth tax and death duties to fund an old age pension; vetoed by the House of Lords to protect hereditary property; House of Lords power of suspensory veto removed by Parliament Act of 1911. |

| 1912-14 - Third Irish Home Rule Bill, passed under the terms of the Parliament Act after House of Lords defeats and incorporated as law with Royal Assent as the Government of Ireland Act 1914 but suspended during World War I. |

|

| 1920 - Fourth Irish Home Rule Act, followed by the Government of Ireland Act (1920) which created a separate parliament for Northern Ireland and provided the framework for Home Rule governments in North and South within the United Kingdom. |

| 1922: Irish negotiators including Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins meet Lloyd George, Lord Birkenhead (Smith), and others to agree an Anglo-Irish Treaty, London 1922. With the signing of the Treaty in Dec. 1922, the de facto situation established by British Acts of Parliament was endorsed - i.e., the operation of a Home Rule governments in Northern Ireland and the South - now styled the Irish Free State by analogy with the Congo Free State. |

|

| The above chronology has been compiled from Wikipedia entries and sundry reference works. [Sept. 2014.] |

Oscar Wilde reputedly remarked, on having Carson pointed out to him with comments on his likelihood of his reaching the top in public affairs, ‘Yes, and one who will not hesitate to trample on his friends in getting there.’ Later, on hearing that Carson had taken Lord Queensbury’s brief, Wilde said, ‘No doubt he will perform his task with all the added bitterness of an old friend.’ (Quoted in Merlin Holland, Wilde Album, pp.30, 123).

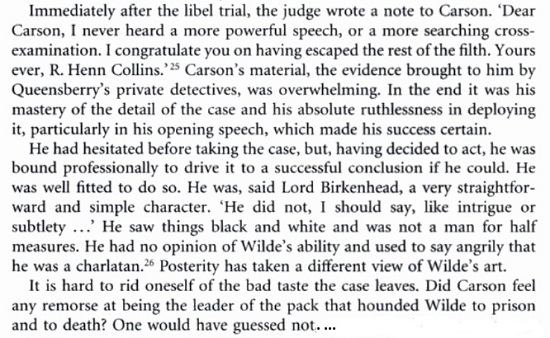

| Carson’s Conduct at the trial of Oscar Wilde |

|

| From Geoffrey Lewis, Edward Carson: The Man Who Divided Ireland (London: Hambledon Continuum [Bloomsbury] 2006), p.45 [available online; accessed 17.07.2021.) |

[ top ]

Frederick H. Crawford (1): Carson’s leading role the Larne gun-running was recounted in his Guns for Ulster (Belfast 1947), cited in George Dangerfield, The Strange Death of Liberal England (London: Constable 1932; rev. edn. 1970), ‘The Guns of Larne’ [chap.].

Frederick H. Crawford (2): Crawford’s widely-credited assertion that he signed the Ulster Covenant of 1912 in his own blood has been put in doubt by scientific evidence following the analysis of the signature by Dr Alastair Ruffell (QUB) using the Luminol test in 2012 - see BBC News (27 Sept. 2012) > online.

Brian Inglis (Downstart, 1990), records that Sir Edward Carson prosecuted Angel Anna, the madam of a brothel, who was sentenced to seven years in prison.’ p.200; see further under Lola Montez, infra.)

Drivel: In his play Saint Oscar (1989), Terry Eagleton makes Carson ask Wilde in court if he is not talking ‘unbelievable amount of utter drivel.’

Portraits: There is a caricature of Carson in full-length profile addressing parliament from the dispatch box by “Lib” [i.e., Liberio Prosperie], in Vanity Fair (3 Nov. 1893).

Play/film: Carson modelled for Sir Robert Morton in Terence Rattigan’s play The Winslow Boy and was played by Robert Donat in the 1948 film.

[ top ]