|

| Life |

| 1821-61 [vars. 1818; c.1820; b. pseud. of [Marie Dolores - hence “Lola”] Eliza [Rosanna] Gilbert; Gräfin (Countess) von Landsfeld; known as “Lollita” by Ludwig I; named Mrs Eliza Gilbert on her grave-stone in Greenwood Cem., Brooklyn, NY] b. 7 Feb. 1821, at Grange, Co. Sligo [var. Limerick], dg. of Capt. Gilbert, a penniless Scottish officer, arriving with his regt. in Ireland in Dec. 1818; and a 14-year old milliner, herself the illeg. dg. of Sir Charles Oliver, a High Sheriff of Cork and MP for Kilmallock, last of four with his mistress Mary Green, born in the year of his marriage at 40 and subseq. in receipt of £500 each in his will; the young couple were married at Christ Church, Cork, with family notices, where his regiment had moved; lived at King House, Boyle, Co. Roscommon, and then in Liverpool before going to India, 1823; Gilbert - whom she called Adjutant-General to Lord Auckland, Viceroy - dies of cholera soon after on arrival, 1864; Eliza raised by her mother and Capt. [afterwards Gen.] George Craigie, whom her mother married in India; sent home to Scotland for education with her caring step-father’s Presbyterian grandfather, Patrick Craigie at Montrose, nr. Dundee, 1827, [aetat. 9], and later in Sunderland with his step-aunt Catherine Rae, who moved south to Monkwearmouth, Durham, and established a school there, 1831; next attended the Misses Aldridges’ Ladies’ Boarding Academy, a finishing-school on Cambden Circle [actually a crescent] in Bath; at 16 [var. 17] she was apparently promised a Sir Abraham Lumly to eloped instead Lt. Thomas James, a penniless Irish lieutenant [‘poor ensign’ - acc. Emily Eden, dg. of Lord Auckland in her Indian diary], in 1837 - he being 27 and apparently the friend of her mother from shipboard times; visited Ireland, unmarried, first staying in a Westmoreland St., Dublin, and then at his family home in Ballycrystal House, Co Wexford; greatly bored by Anglo-Irish country-house life - especially the ‘endless cups of tea’ consumed by his female relatives (Do.); afterwards married with her mother’s consent but without her blessing; |

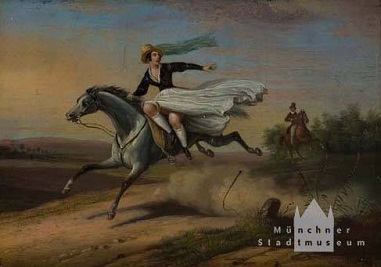

| travelled to India to Thomas, reaching Calcutta on 25 Jan. 1839; stationed at Karnal; contracted malaria in India; vacationed in Simla, Sept. 1839; discovered her husband to be violent and unfaithful [with a Mrs. Lomer]; reunited with her mother in Calcutta and afterwards returned to England, 1840; placed in the care of David Craigie, a family member in Perth, Scotland, but refused to stay with the “blue Calvinist”; remains in London with the £1,000 income settled on her [which ‘disappeared .. by a sort of insensible perspiration’]; learnt stage-craft from Fanny Kelly and trained in Spanish and acquired a Spanish accent; divorce proceedings initiated by James, citing George Lennox, 1842; commenced a stage career in London as Donna Lola Montez, exotic dancer and war-widow at Her Majesty’s Theatre, 3 June 1843, but soon detected as Mrs. James and castigated in the press; travelled to Spain and elsewhere in Europe to study her rôle - purportedly visiting the Montalvos from whom she claimed to be descended; unsuccessful operatic début in Le lazzarone by Halévy, Paris 1844; reputedly had affairs with Franz Liszt, Alexandre Dumas, and newspaper editor Henri Dujarier - who died in a duel with a political opponent Beauvallon, having left a letter to her excuseing his absence from her bed; travelled to Bavaria with an introduction to the royal court; met in Munich King Ludwig I of Bavaria (aetat. 60), in her character as a Spanish dancer, 8 Oct. 1846 - and apocryphally reported to have removed clothing to show how little she needed stays [to support her bosom]; created Countess of Landsfeld by him (25 Aug. 1847), with a substantial life-pension [£2,000 p.a.; afterwards discontinued in at regime-change]; Ludwig commissioned a portrait by Josef Stieler for his Gallery of Beauties [Schönheitsgalerie], now displayed in Nymphenburg Palace (Munich); he commissioned another in oil from Wilhelm von Kaulbach, which the King rejected, 1847; became his mentor in political matters, turning him against ‘the cloven foot of Jesuitism’; instigated his closure of the universities and was condemned by the republican students [‘Down with the concubine!’]; banished ‘hopelessly’ [Autobiography] from Bavaria two weeks before his forced abdication, 1848; |

| vainly awaited Ludwig in Switzerland, and moved to London, where she married an English cavalry officer, George Trafford Heald in Paris, 1849 - though debarred by terms of her divorce with James from remarriage; exchanged letters with Ludwig I, thenat Berchtesgaden, denying that she was ‘in love’ with Heald (‘it is a completely different sentiment’) and offering to renounce the intended marriage; hounded by an outraged aunt of Heald, subjected to satirical cartoons and removed to the continent in face of a bigamy scandal, living in France and Spain; Heald apparently dies by drowning in Europe; Montez travels to America, arriving ; photographed by Meade Bros. in New York, 22 Dec. 1851; a daguerrotype portrait is made by Marcus Root, accompanied by another in which she links arms with Light in the Clouds, an Arapaho Chief in the studio, 2 Feb. 1852; (Harvard. Lib.); successfully toured her stage-show Lola Montez in Bavaria in the USA and Australia, investing profits in gold speculation in Sierra Nevada and Australia; reached San Francisco, on the Northerner, 21 May 1853, and played Lady Teazle in Sheridan’s School for Scandal five days later [27 May]; m. Patrick Purdy Hull, a newspaper man whom she had met on board, 2 July 1853, in a ceremony at San Francisco Mission Church, but separated after two months and settled at Grass Valley (Ca.), late Aug. 1853; a physician who was afterwards murdered was as correspondent in the ensuing divorce; remained some years in Grass Valley, latterly restored as a historical landmark; travelled to Australia as a dancer, Aug. 1855; danced the Spider Dance on stage in Adelaide [Sandhurst (Victoria), and Melbourne], Sept. 1855, incurring the moral wrath of polite society; performed the same before 400 miners to rapturous applause at Castlemaine, but alienated the audience in response to mild heckling, April 1856; later attacked the editor of the Ballarat Times with a whip; |

| returned to San Francisco, May 1956 - suffering the loss of her lover-manager Frank Folland [var. Noel Follin] who went overboard 18 days from the Golden Gate; reached San Francisco, 26 July 1856, writing to Folland’s widow with an offer of support; settled in San Francisco with a house-hold of exotic birds from Australia incl. talking cockatoo, and the lap-dog Gip; returns successfully to the San Francisco stage, Aug. 1856; met Charles Chauncey Burr, a journalist an elocutionist who prepared her for a lecturing career; with him, she encountered the evangelist Thomas Harris who shaped her ultimate religious outlook; moved into the Follin [sic Seymour] home at Stuyvesant Place (NY), with Follin’s step-mother [Susan Dorothy Follin] and his sister Miriam, Jan. 1857; plays Forbes Theatre, Providence with Miriam [“Minnie”] and afterwards in Albany, Buffalo, &c.; inaugurated her lecture career with “Beautiful Women” in Hamilton, then Buffalo, where she introduced her second lecture, “The Origin and Power of Rome” [later published as “Romanism ”], July-Aug. 1857; lectured in Montreal; first steamer trip to England, autumn 1857; deceived by marriage promises of exiled Austrian Prince Sulkowski in Paris; returns to Boston via Liverpool, Jan. 1858; appeared as a character-witness in the debt case of David Wemyss Jobson; |

| wrote up her lectures as a book at the end of season, residing at Yorkville, NY, summer 1858; gave charity lecture to rebuilt Good Shepherd [Episcopalian] Church, Oct. 1858; travelled to Ireland on new New York-Galway steamship Pacific, 8-23 Nov. 1848, with Burr and his father Heman (as tour manager); visited Cork and Limerick; defended herself in the Dublin press against charges of courtesanship and bad faith in her connections with Dujarier, and Ludwig I; lectures on “America and Its People” in the Rotunda, Dublin; 8 Dec 1858; gave “Comic Aspects of Fashion” as her second Rotunda lecture and “English and America Character Compared” as the third; spoke of anarchy in America (e.g., vigilantes) and the superiority of monarchy as a system of government; lectured twice in Cork and once in Limerick (skipping Belfast) before returning to England, 1858; spoke in Edinburgh, and Glasgow; proceeded to Sheffield, Nottingham, Leicester, Wolverhampton, and Worcester and York (16 Feb. 1859); lectured on “Slavery in America”, condemning the Abolitionists but acknowledng the evil of the institutions; also spoke on the topics of “Strongminded Women” and “Women’s Rights in America” - accusing women of imitating the follies of men; resided at Park Lane with dwindling income until the lease was sold; moved for shelter to Derby as country-house guest of an English couple; attended Methodist services; quarrelled with her host and returned to London; took ship to America from Southampton on the Hammonia, logged as Mrs. Heald, Sept. 1859; rebutted charges of anti-Americanism in newspaper letter; gave lecture on “John Bull at Home”, 15 Dec. 1859; |

| Montez issued The Art of Beauty (1858; French trans. 1862) - which exposes the lucrative concoctions of fake cosmetic products and recommends some inexpensive recipes of her own, together with moderation, freedom from alcohol, exercise, and personal hygiene (frequent baths); she turned philantropist on recommendations of a former schoolfriend, and spent last years visiting former prostitutes in Magdalen Society [Asylum], 88th St., NY; a heavy smoker, she reputedly suffered from tertiary syphilis; suffered a stroke in June 1860, and succombed to pneumonia following an outdoors walk in New York during convalescence, 17 Jan. 1861; received unwelcome visit by her mother Eliza Craigie, apparently seeking to inherit her supposed fortune, autumn 1860; nursed in New York by Maria Buchanan and husband; attended inher final illness by her minister Francis Lister Hawks; assigned $300 to the Magdalen Society; d. in Brooklyn [aetat. one month short of 40; 41; vars. 42 &c.]; bur. in Green-wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, under a now-eroded gravestone with an illegimate epigraph bearing the inscription “Mrs. Eliza Gilbert, died 17 January, 1861, AE 42 [sic])” [from a 19th c. photograph]; she was survived by [now] Capt. Thomas who went on permanent leave and then retired in unhappy circumstances, 1856; letters were exchanged between Mrs Buchanan and Ludwig I after her death; much misinformation about her origins and career has been circulated in standard references works, viz., The American Cyclopaedia (1879); she has often been called the most famous Victorian woman after Queen Victoria; the authoritative life is by Bruce Seymour (1996, rep. 2008); subject of numerous biographies and novels incl. Marion Urch, An Invitation to Dance (2009) [as infra]. DIW |

| A Gallery | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| The legacy ... | ||||

|

Montez is remembered as a proto-feminist and a radical exponent of individualism. Her breaches of decorum - real and imagined - which shocked and thrilled contemporaries are taken as tokens of an anti-conventional attitude pointing towards a philosophy of personal liberation. Contradictorily, her involvement in social welfare for prostitutes in New York is sometimes yoked to a confessional narrative of redemption through in evangelical Christianity while her flighty character is seen as a redeeming trait in a secular-liberal context.

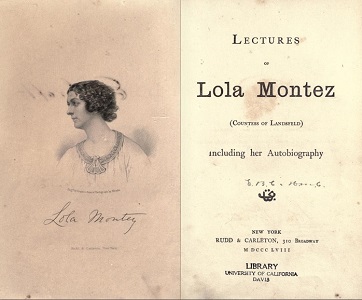

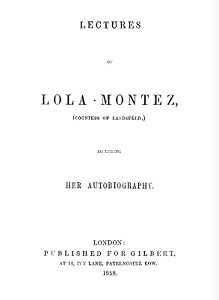

Apparently six lectures - published as Lectures [...] including an Autobiography in New York and in London during 1858 - were planned but only two produced at the first season in Yorkville (NY) during the summer of 1857. These proved enough for the first tour, though others were shortly added. In scope and style, each oration, as the series as a wholedisplays a synoptic knowledge of history and literature which comes as a surprise in a woman with her career but is not untypical of the material available in sundry volumes about woman-heroines and “Female Worthies” published in the Victorian period. (The Anglo-Irishwoman E. Owen Blackburne’s Illustrious Irishwomen of 1877 is a case in point.) Nevertheless, her anti-feminism has a fresh tone which evidently pleased its audience, sometimes to the extent of an ovation, and she cannot have lost friends when she bereated the ‘gentlemen’ present for unfairly judging women by standards which they do not trouble to observe themselves.

- and, still later, she harps on Milton again when she recounts the progress of age in young women - setting the ‘meridian’ of beauty a little earlier than modern taste and morals allow: ‘Mary passes her teens, and approaches her thirtieth year [...] she may then consider her day at the meridian [...] A few short years, and the jocund step, the air habit, the sportive manner, must be all exchanged for the “faltering steps and slow.”’ (p.110.) Here she is slightly misquoting the last lines of Paradise Lost which show us Adam and Eve departing from Eden, ‘hand in hand, with wandering steps and slow”. (Milton does, however, used “faltering” elsewhere where ‘Old Anarch’ addresses Satan as one of his own: ‘with faltering speech, and visage uncomposed / “I know thee, stranger; who thou art [...]”’ In this case, therefore, the erroneous allusion suggests the depth of her familiarity with its classic source. |

||||

|

Note there is a recurrent confusion in the biographical literature about Montez regarding the manner of her first marriage - whether she ‘eloped’ with Lt. Thomas or was given to him by her mother. By her own autobiographical account, her mother planned to marry her off as a teenager to an sixty-year-old man called Sir Abraham Lumly - a suspicious theatrical name too reminiscent, perhaps, of Fielding and Sheridan to be credible - causing her to turn to her mother’s younger friend, Capt. Thomas James, who then took advantage of her distress by eloping with her himself. In that account she makes no mention of improper relations between her married mother and Capt. James, though it she does say that it was he who told her of the intended marriage-pact and hence he was both the instigator of her misery and the beneficiary of it. Probably, her intention was to criminalise Thomas in writing it thus in retrospect. Certainly he comes out of it as a very untrustworthy friend and a very greedy man. In reality it may have been quite different and her love for the twenty-seven-old ensign may have been as sincere, at its moment, as first love often is. And since he was a ‘poor ensign’ - as Emily Eden, a kinswoman of the Viceroy of India Lord Auckland, puts it, he must have considered that he was getting a pretty young wife very cheap on the eve of his posting in India - where the couple found themselves after a shot-gun marriage in a very short time. Whether he thought he was cheating on Mrs. Craigie is another question, but the latter’s epistolary lament at the wasted education which is recorded in the exhaustive biography by Seymour suggests that her indignation was very real for either reason: the defection of a lover or the theft of a daughter. In a general way, it all bespeaks a highly disordered way of life in the home where Lola Montez raised.

|

[ top ]

Works

|

|

Bibliographical details

Lectures and Autobiography (1858)

1.] Lectures of Lola Montez (Countess of Landsfeld): Including her Autobiography (London: Published for Gilbert, 14 Ivy Lane, Paternoster Row 1858), 192 +[6]pp. [incls. A Sketch from Fanny Fern’s Portfolio, viz., “Helen, The Village Rosebud”, as pp.185-92.; copies in Cambridge UL & LSE; another copy in Emory UL - available at Internet Archive, online; see extracts].2.] Lectures of Lola Montez (Countess of Landsfeld) including her Autobiography (NY: Rudd and Carleton, 310 Broadway: MDCCCLVIII [1858]), 292pp., ill. [front.; [8]pp. of publisher’s catalogue at the end - copy at Univ. of California at Davis Liberary available in Internet Archive - online].

New York and London Editions of Lectures of Lola Montez, including her Autobiography (both 1858) Rudd & Carleton, 310 Broadway[, New York] Gilbert [self], Paternoster Row Front plate on London Edn.

Ch. Contents 1st London Edn. American Edn. 2nd London Edn. I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

VIII.Autobiography. Part I., . . . . . . . . . .

” ” II., . . . . . . . . . .

Beautiful Women, . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Gallantry, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Heroines of History, . . . . . . . . . . . .

Comic Aspect of Love, . . . . . . . . . .

Wit and Women of Paris, . . . . . . . . .

Romanism, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

36

79

53

109

131

145

169

55

83

125

171

207

231

2651

33

53

83

116

142

158

183[ Available at Internet Archive, online. ] Note: Both the American edition and the second London edition (Blackwood) prefix a commendatory notice on Lola Montez from The American Law Journal. Note 1: The two parts of the “Autobiography” which begin the text are styled “lectures” when spoken of in the writing itself: - viz., "Don’t misunderstand me - I am not promising in my next lecture to explain that riddle, Lola Montez - that is a thing I have not guessed myself yet - but I shall faithfull go over this wild episode of life (horse-whippings and [34] all without the least disposition to shield my subject from the open eyes of the critical world.’ (pp.34-35.) [For remarks on “whipping”, see under W. H. Russell, infra.]

[ Note 2: The essay on “Gallantry” is actually a well-read account of the history of the Troubadours of Provence: ‘That, ladies, is the way they used to make love in the age of the Troubadours. Love was certainly a very earnest, and sometimes a very fearful thing in those days.’ (p.84.)

[ Note 3: Occasional remarks make it clear that the essays were written for an American audience - viz., ‘I suppose it is not singular in this [my italics] country to find the poorest cobbler, whose little shanty is next to the proud mansion of some millionnaire, a man of really more mental attainments than his rich and haughty neighbour; in which case the millionnaire will do well to look to it, that the cobbler does not make love to his wife; and if he does, nobody need care much, for the millionnaire will be quite sure to reciprocate. / The great statute, “tit-for-tat,” is, I believe, equally the law of all nations.’ (p.136.) Further, ‘Likewise, marital arrangements in Salt Lake City [sic italics] are considered “very funny”’ - though ‘it would no longer be considered a subject of amusement if such practices were brought to our own doors.’ (p.141.)]

§

2.] The Arts of Beauty; or, Secrets of a Lady’s Toilet, with Hints to Gentlemen on the Art of Fascinating (NY: Dick & Fitzgerald [1858]) - available at Internet Archive - online]; Do., [rep. edn.] (NY: Echo Press 1978), xiii, 111pp. [Date added by hand on the copy at Emory Univ. Library; accession date, 15 May 1891, gift of Dr. S. G. Green.]

| Table of Contents [chapter list] |

| I: Female Beauty; II: A Handsome Form; III: How to obtain a Handsome Form; IV: How to acquire a Bright and Smooth Skin; V: Artificial Means; VI: Beauty of Elasticity; VII: A Beautiful Face; VIII: How to obtain a Beautiful Complexion; IX: Habits which destroy the Complexion; X: Paints and Powders; XI: A Beautiful Bosom; XII : Beautiful Eyes; XIII: Beautiful Mouth and Lips; XIV: A Beautiful Hand; XV: A Beautiful Foot and Ankle; XVI: Beauty of the Voice; XVII: Beauty of Deportment; XVIII: Beauty of Dress; XIX: Beauty of Ornaments; XX: Importance of Hair as an Ornament; XXI: How to obtain a good Head of Hair; XXII: To prevent the Hair from falling off; XXIII: To prevent the Hair from Turning Grey; XXIV: How to soften and beautify the Hair; XXV: To remove Superfluous Hair; XXVI: How to color Grey Hair; XXVII: Habits which destroy Beautiful Hair; XXVIII: Blemishes to Beauty. Fifty Rules in the Art of Fascinating [102]. Index [129-32.] |

| Dedication |

| TO / ALL MEN AND WOMEN / OF EVERY LAND, / WHO ARE NOT AFRAID OF THEMSELVES, / WHO TRUST SO MUCH IN THEIR OWN SOULS THAT THEY DARE TO STAND UP / IN THE MIGHT OF THEIR / OWN INDIVIDUALITY, / TO MEET THE TIDAL CURRENTS OF THE WORLD, THIS BOOK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED, BY / THE AUTHOR. |

| [ Available at Internet Archive - online. Note that this copy from the Emory University Library contains marginal tick-marks against the various recipes and prescriptions suggested by the author, indicating that the original reader treated it as a practical manual on the subject.] |

[ top ]

Criticism| Standard biography |

|

| German responses |

|

| Commentary & biography |

|

| Irish commentaries |

|

| Biographical fiction |

|

|

| General studies |

|

| Cinema & media |

|

[ top ]

Commentary

Cork Examiner (13 Dec. 1858) - report on Lola Montez’ 2nd lecture Dublin: ‘Madame Montez, Countess of Landsfelt, delivered her second lecture the Rotundo [sic] last Friday evening, having for the subject “The Comic Aspect of Fashion”. The arrangements were much better than on the former occasion [...]’ [Available at Genes Reunited > Seach British Newspapers > - online; accessed 11.12.2014. Note 30+ newspapers from Dublin, Louth, Belfast, Cheshire, Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cumbria, &c., record this event with similar (copied?) accounts of the ‘warm applause’ which greeted the speaker.]

Bruce Seymour, Lola Montez: A Life (2008):The American Law Journal - Extract prefixed to American edition of Lectures [... &c.] (1858): ‘Let Lola Montez have credit for her talents, intelligence, and her support of popular rights. As a political character, she held, until her retirement from Switzerland, an important position in Bavaria and Germany, besides having agents and correspondents in various parts of Europe. On foreign politics she has clear ideas, and has been treated by the political men of the country as a substantive power. She always kept state secrets, and could be consulted in safety in cases in which her original habits of thought rendered her of service. Acting under her advice, the king had pledged himself to a course of steady improvement to the people. Although she wielded so much power, it is alleged that she never used it for the promotion of unworthy persons, or, as other favorites have done, for corrupt purposes; and there is reason to believe that political feeling influenced her course, not sordid considerations.’ (Prefixed to the American edition, 1858, p.[5].)

|

||||||||

Sample pages: “The Joys of Married Life” [from Chap. 3 & 17]. |

|

|

[...] |

|

|

| —Op. cit., pp.18 & 183; available at Google Books - online. [Chapter 1 of this work is available to view at Amazon Books - online while all chapters except Chaps. 26 & 28 are available to view at Google Books - online - accessed 12.12.2014.] | |

Note: Bruce Seymour has lodged his copious research files on Lola Montez at www.zpub.com > History > &c. - online. These include a Chronology of her life, an account of Persons associated with her, a Bibliography and Critical review of all the major biographical literature, as well as copies of all contemporary Newspaper reports about her. The front page is structured to allow for downloads of each of these in word-processor format.

[ top ]

Helen Meany, ‘¡Hola Lola!’, in The Irish Times (13 June 2009), [Weekend] Magazine [q.p.]: ‘[...] Author Marion Urch loved the Orphüls film as a student, and when she learned that Montez was Irish - born Eliza Gilbert - she was hooked. Her new novel, An Invitation to Dance, explores Eliza’s Irish origins, opening in Cork in 1820 where her mother, a teenage milliner’s apprentice, first met her father, an ensign in the British army. By the time he discovered that she was the illegitimate daughter of an Anglo-Irish lord, she was already pregnant. A shotgun wedding preceded an army posting to India, with their new baby girl in tow./ “The fact that she was Irish was fundamental to my understanding of Lola Montez,” says Urch. “I read everything I could about her, but most of it was quite hostile. I became determined to unlock her character, and rescue her from all the B-movie clichés and the implausible life story. None of the biographies I read really thought about her in the context of what life was like for women in Ireland and England at the time. Even the idea, always repeated, that she was a bad dancer: she did get some good reviews, in fact. It’s just that her dancing seemed raw and unrefined because it was based on flamenco. It came as a shock to audiences used to seeing ballet.” / In Urch’s first-person narrative, the young Eliza Gilbert observes the casual cruelties of her world through sensitive eyes. Hurt by her mother’s indifference, she is passed like a parcel among nurses and servants, and eventually sent back from India to a boarding school in Bath on the death of her father. Exile, displacement and constant movement define her life’s history.’ (Available at Marion Urch’s website > online - or see copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

[ top ]

Quotations

«The Arts of Beauty (1858) - Dedication: ‘To all men and women of every land, who are not afraid of themselves, who trust so much in their own souls that they dare to stand up in the might of their own individuality to meet the tidal currents of the world.’ (Cited by Marion Urch, Facebook - 11.12.2014; also given a concluding summary phrase in the Epilogue of Bruce Seymour, Lola Montez: A Life, 1996, 2008, p.401.)

Women’s vanity?: ‘The Baroness de Stael confessed that she would exchange half her knowledge for personal charms, and there is not much doubt that most women of genius, to whom nature has denied the talismanic power of beauty, would consider it cheaply bought at that price. And let not man deride her sacrifice, and call it vanity, until he becomes himself so morally purified and intellectually elevated, that he would prefer the society of [xiv] an agly woman of genius to that of a great and matchless beauty of less intellectual acquirements. All women know that it is beauty rather than genius, which all generations of men have worshipped in our sex. Can it be wondered at, then, that so much of our attention should be directed to the means of developing and preserving our charms? When men speak of the intellect of woman, they speak critically, tamely, coldly; but when they come to speak of the charms of a beautiful woman, both their language and their eyes kindle with the glow of an enthusiasm, which shows them to be profoundly, if not, indeed, ridiculously in earnest. It is a part of our natural sagacity to perceive all this, and we should be enemies to ourselves if we did not employ every allowable art to become the goddesses of that adoration. Preach to the contrary as you may, there still stands the eternal fact, that the world has yet allowed no higher “mission” to woman, than to be beautiful. Taken in the best meaning of that word, it may be fairly questioned if there is any higher mission for woman on earth. But, whether there is, or is not, there is no such thing as making female beauty play a less part than it already does, in the admiration of man and in the ambition of woman. With great propriety, if it did not spoil the poetry, might we alter [xv] Mr. Pope’s famous line on happiness, so as to make it read —

“beauty! our being’s end and aim.”

My design in this volume is to discuss the various Arts employed by my sex in the pursuit of this paramount object of woman’s life. I have aimed to make a useful as well as an entertaining and amusing book. The fortunes of life have given to my own experience, or observation, nearly all the materials of which it is composed. So, if the volume is of less importance than I have estimated, it must be charged to my want of capacity and not to any lack of information on the subject of which it treats.

The HINTS TO GENTLEMEN ON THE ART OF FASCINATING, I am sure, will prove amusing to the ladies. And I shall be disappointed if it fails to be a useful and instructive lesson to the other gender. The men have been laughing, I know not how many thousands of years, at the vanity of women, and if the women have not been able to return the compliment, and laugh at the vanity on the other side of the house, it is only because they have been wanting in a proper knowledge of the bearded gender. If my “Hints” shall prove to be a looking- glass in which the men can “see themselves as others [xvi] see them” they will, I hope, not be unthankful for the favor I have done them. And if my own sex receiyes this book in the same spirit with which I have addressed myself to its subject, I shall be happy in the conviction that I have rendered my experience serviceable to them and honorable to myself.’ / Lola Montez. (pp.xiv-xvi.)Note that all of the hints are ironic, describing behaviours in men which are the least likely to win the admiration of a sensible woman. These include professing that his object is to please all their sex and not one particular member of it, pronouncing himself an atheist, take his ease and throw his arm over the their chairs in a proprietary fashion, recounting their triumphs overother men, ‘dance with all the might of your body’, ordering three times too much food in expensive restaurants, ‘gassing’ (talking about meetings with important peoplesporting jewelry in abundance, ), join the ‘danglers’ (willing objects of mock flirtations), and so on ... In order words - madly competitive or foolishly effeminate. [BS]

Another Hint: ‘Gentlemen, if you please, if you would have your homes hold no hearts but yours, see to it that your own hearts are always found at home.’ (“Beautiful Women”, in Lectures [... &c.] (1858, p.63.)

[ top ]

| Autobiography (i.e., Lectures .. including Autobiography, London: Gilbert 1858) |

|

[Introductory remarks ...] [Account of family and birth...] [The first marriage ...] [Note: The orig. vol. here erroneously prints pp.13 & 14 - both number and contents - as 14 then 13; see online.] [...] ‘Of Lola Montez’ career in the United States there is not much to be said. On arriving in this country she found that the same terrible power which had pursued her in Europe, after the blows she had given it in Germany, held even here the means to fill the American press with a thousand anecdotes and rumours, which were entirely unjust and false in relation to her. Among other things, she had had the honor [49] of horse-whipping hundreds of men whom she never knew, and never saw. But there is one comfort in all these falsehoods, which is, that these men very likely would have deserved horse-whipping, if she had only known them. As a specimen of the pleasant things said of Lola Montez, I am going to quote you from a book, entitled the Adventures of Mrs. Seacole, published last year [viz., 1857] in London, and edited by no less of a literary man than the gifted correspondent of the London Times, W. H. Russell, Esq. Mrs. Seacole is giving her adventures at Cruces, between here and California. She says: “Occasionally, some distinguished passengers passed on the upward and downward tides of rascality and ruffianism, that swept periodically through Cruces. Came one day, Lola Montez, in the full zenith of her evil fame, bound for California, with a strange suite. A good-looking, bold woman, with fine, bad eyes, and a determined bearing, dressed ostentatiously in perfect male attire, With shirt-collar turned down over a velvet lappelled coat, richly worked shirt-front, black hat, French unmentionables, and natty polished boots with spurs. She carried in her hand a handsome riding-whip, which she could use as well in the streets of Cruces as in the towns of Europe; for an impertinent American, presuming, perhaps not unnaturally, upon her reputation, laid hold jestingly of the tails of her long coat, and, as a lesson, received a cut across his face that must have marked him for some days. I did not wait to see the row that followed, and was glad when the wretched woman rode off on the following morning.”’ (Ibid., pp.49-50.)

[ top ] [Lecture:] “Beautiful Women” ‘In Turkey I saw very few beautiful women. The style of beauty there is universally fat. Their criterion for a beautiful woman is that she ought to be a load for a camel. They are, however, quite handsome when young, but the habit of feeding them on such things as pounded rose leaves and butter, to make them plumb, soon destroys it. The lords of creation in that part of the world treat women as you would geese - stuff them to make them fat.’ (Ibid., p.61.)

[Fashion-history:]

Quotes a ‘shameless confession’ of Lord Chesterfield: ‘I will own to you, under secrecy of confession, that my vanity has very often made me take great pains to make many a woman in love with me if I could for whose person I would not have given a pinch of snuff.’ (Ibid., p.98.) This dictum comes under the heading of ‘a modern gallant, or flirt, [...] a poor imitation of [...] the genuine gallant of the days of chivalry.’ (Ibid., p.96.) [On tepid baths:]

[Love in America:]

[ top ] [Lecture:] “Heroines in History” [See also her remarks on Burke’s ‘violence of women’ - under Edmund Burke, supra.] ‘No, the wise and cunning of my sex all know that, in politics, they must not even let the right hand know what the left hand doeth. And what do I care who carries the votes to the box, if I am allowed to say how the voting shall be done? The will of every intellectual and adroit woman does go to the ballot-box, with a voice a hundred fold more potential than if she rushed into the coarse crowd to carry it there herself. In such a contact the mass of women would only lose the delicacy and refinement which now constitute their only charm, without getting any benefit for the terrible sacrifice. The kitchen and the parlour, and all the sacred precincts of home, would be immeasurably impaired, while there would be no gain whatever to the councils of the state. If a woman is qualified to be a happy wife and a good mother, she need never look with envy upon the more gifted woman of genius, whose mental powers, unfitting her for the stormy arena of politics, may have unfitted her for the quiet walks of domestic life. In the woman of rare mental endowments, there may be a necessity in her own nature, forcing her into a field of action altogether different in its sphere from the duties usually allotted to woman. Where this is the case, she must [127] obey her destiny; but the woman who has only those humbler charms which fit her to be the light and the presiding goddess of the beautiful circle of “home,” is really to be envied by her more gifted sister whose powers tempt her out upon the turbulent sea of politics and diplomacy. ‘What do men mean when they call woman the weaker sex? Not, surely, that she is less strong and brave of heart and purpose to meet the tidal shocks of life! Not that she is not every whit the peer of man in all the elements of heroism and genuine nobility of soul! That masculine philosophy which regards and would treat woman as an inferior beings, is not only an insult to that God who created her as the equal companion of man, but it is contradicted by every stage of history and experience. Her excellence may be generally displayed in a less ostentatious field than man’s, but still the idea of perfect equality is not impaired on that account. [ top ] [Lecture:] “The Comic Aspect of Love” [ top ] [Lecture:] “Romanism” |

[ top ]

References

Encylopaedia Britannica (1911) describes Montez as ‘dancer and adventuress, the daughter of a British army officer, [...] born at Limerick, Ireland, in 1818 [...]’ and later: ‘She soon proved herself the real ruler of Bavaria, adopting a liberal and anti-Jesuit policy’.(Available online; accessed 11.12.2014.)

The American Cyclopaedia (1879): ‘[..] a favorite of Louis I. of Bavaria, born in 1824, died at Astoria, N. Y., June 30, 1861. According to some authorities she was a native of Montrose, Scotland, and the illegitimate daughter of a Scottish officer named Gilbert, and according to others she was born in Limerick of an Irish father. Her mother was a Creole who successively lived with or was married to natives of Spain and Great Britain, whence the conflicting accounts of Lola’s origin. She received a good education in England, and married an officer named James, whom she accompanied to India. She left him after several years and led an adventurous life in Paris and other capitals. In 1846 she appeared in Munich as a Spanish ballet dancer, and captivated the heart of the Bavarian king by her beauty and accomplishments. Her influence became so great that the ultramontane administration of Abel was dismissed because that minister objected to her being made Countess Landsfeld. The students of the university were divided in their sympathies, and conflicts arose shortly before the outbreak of the revolution of 1848, which led the king at Lola’s instigation to close the university. But a more violent outbreak early in March obliged the king to reopen that institution, and to discard Lola, who fled. Although her first husband was still alive, she contracted in 1849 a second marriage with an English officer named Heald. Prosecuted for bigamy, she went with him to Madrid, but soon deserted him. The two husbands died not long afterward. In 1852 she gave performances in New York, New Orleans, and San Francisco, and succeeded best in dramatic entertainments setting forth her own adventures. In California she married a Mr. Hull, but he did not live with her long. In 1855 she appeared at Melbourne, Australia, and subsequently lectured in the United States and England. She returned to New York in 1859, reformed her life, and died in poverty in a sanitary asylum. [Bibl. The Story of a Penitent (24mo, New York, 1867).]

[ top ]

Notes

Brian Inglis (Downstart, 1990), quotes an account given in Wilson Harris’s Life So Far [q.d.] of the Spectator office at 99, Gower St. [London], formerly a brothel run by ‘an adventuress of dubious, but mainly American, origin (for all that she claimed to be the extra-matrimonial offspring of the mad King Ludwig of Bavaria and the Spanish dancer Lola Montez [...]’. The madam, Angel Anna, was prosecuted by Sir Edward Carson and sentenced to seven years in prison. (Inglis, op. cit., p.200.)

Harriet Steel, Becoming Lola ([Ilford]: YouWriteOn Publications 2010), 315pp. - Summary: ‘“A woman who has sufficient intellect to render herself of independent mind ought also to be able to assume the quills of a porcupine in self-defence.” Wildcat and temptress with a mind as sharp as her tongue, the nineteenth-century adventuress, Lola Montez, followed her own advice and became, after Queen Victoria, the most famous woman in the Western world. Born Eliza Gilbert in 1821 to an Ensign in the British Army and his cold Irish wife, she faced a life of misery when her mother arranged a marriage to an elderly man whom she had never met. She fled and became notorious in London society. When it turned against her, she used her looks and the craze for Spanish dancing to re-invent herself as Lola, the widow of a Spanish hero killed in the Civil War. She set out to conquer Europe. Then the King of Bavaria fell for her charms and the stage was set for a scandal that would change the course of history.’ [See COPAC - online.]

Marion Urch, author of An Invitation to Dance (Dingle: Brandon Press 2009), a novel on Montez, is a novelist and short-story writer whose first novel Violent Shadows - ‘where the entanglements of the past erupt into the present in dangerous and unexpected ways’ - appeared in 1996. Invitation was recommended in Books Ireland (Feb. 2009, p.5) and elsewhere. There is a German translation by Christine Pavesicz as Die Tänzerin: Ein Lola-Montez-Roman (Aufbau taschenbuch [digital] 2010). Both the English and the German editions are available as Kindle books at Amazon - online.

Norman Holland, who wrote Lola Montez: Der König und die Tänzerin (Munich: Ehrinwirth 1988), apparently published in German only, also wrote The Green Bottle (1950); The Militants (1970); Watcher in the Shadow: A Play (1973); My Name is Oscar Wilde (1975) Miss Nightingale’s Mission (q.d.); To Meet Oscar Wilde (1999); Three Costume Plays for Women (q.d.); Princess Ascending: A Royal Progress in Two Acts (1976). See also with Michael Adams, Student Workbook and Resources Guide for Core Concepts in Pharmacology (2014) and Textbook Resources for Core Concepts in Pharmacology: Access Code Card (also 2014). [All listed at Goodreads - online; accessed 12.12.2014.]

Namesakes: A namesake (Norman N. Holland, b.1927) is the distinguished literary critic associated with Reader Response Theory, now emeritus from Florida University, who first graduated in electronic engineering and migrated via Law to English literature (PhD) before taking a teaching post at Buffalo Univ., NY in 1966. A gospel singer of the same name died in Nashville in 2014. Another namesake teaches Hispanic literature at Hampshire College, Amherst, MA.

Lola/Estaban: Norman N. Holland has written about the 1999 film Todo Sobre Mi Madre [All About My Mother] by Pedro Almodóvar: ‘The transgendered characters change their names: Agrado (Antonia San Juan) and Lola, formerly Esteban (Toni Cantó). Then there are the confusions of several Estebans. “Esteban” refers to Manuela’s and Lola’s son (Eloy Azorin) who dies early in the film, hit by a car. He is Esteban Two, the middle generation. But “Esteban” also names Rosa and Lola’s child (Esteban Three), and it names “Lola” before her sex change (Esteban One). Esteban One is the father of Estabans Two and Three. There are also two Rosas, the young nun played by the 22-year-old Penélope Cruz, and her cranky mother (Rosa Maria Sardá), a painter of fake masterpieces. [...] none of the traditional markers for the identity of humans or art works in this movie. What Almodóvar offers instead is performance (or, to use current critical jargon, performativity). You are the way you perform yourself. [... &c.]’ (See A Sharper Focus: Essays on Film by Norman Holland [website] - online.)

Lola Montès - (dir. Max Orphüls, 1955) - variously sub-titled “The Sins of Lola Montez” and “The Fall of Lola Montez”: ‘Max Orphüls’ final film (and his only movie in color) is a cinematic tour-de-force masquerading as a biography, in this case a dazzling fictionalized life of the notorious 19th century dancer, actress, and courtesan. A still beautiful, but weary and disillusioned (and, as we later discover, ailing) Lola Montes (Martine Carol) is first seen as the featured attraction at a seedy American circus, appearing at the center of a series of various tableaux depicting the scandalous events for which she is known. With a strangely sincere yet sinister and manipulative ringmaster (Peter Ustinov) providing color commentary, some of it very ironic on two or more levels, the movie flows between these staged recreations in the circus and the events as recalled by the subject. In a series of dissolves, the film takes us through her girlhood with her mother, interrupted when her mother’s lover (Ivan Desni) becomes attached to the daughter; her unhappy marriage and its aftermath; romances with composer Franz Liszt (Will Quadflieg), abduction by a Russian general (in the arms of Cossacks, no less); her affairs across the landscape of Europe with men great and notable; her thwarted aspirations as a dancer; and her romance with King Ludwig I (Anton Walbrook) of Bavaria, which led to her being made Countess of Landsfeld, and, later, to his abdication. The gracefulness of Ophuls’ cyclical narrative, and the transitions between the recalled elegance of the locales, and the people with whom her romances and affairs took place, and the seediness of the circus - where she is also compelled, in the course of performing, to perform as an aerialist - were lost on viewers in 1955. And for many years the movie only existed in a version re-cut without the director’s approval, in which the story was presented in linear fashion. It was only in the 1960’s, long after Orphüls’ death, that efforts were made to restore the original structure, and in 2008 the movie’s original Technicolor luster was restored to its full depth and richness.’ (Bruce Eder, Rovi; see Rottentomatoes - online.) NB: The restored version lasts 1:55 hrs.

[ top ]