Life

| (1896-1974 [Augustine Joseph Clarke]; poet; b. 9 May 1896, Manor St., Dublin, ed. Belvedere College, Mungret College, and UCD, where he was taught by Thomas MacDonagh and Douglas Hyde; appt. university lecturer in English at UCD, succeeding MacDonagh, 1917; suffered a mental breakdown, 1919; entered an unconsummated marriage with Lia Cummins, formalised in registry office, 31 Dec. 1920, the marriage failing soon thereafter; lost his post at UCD, 1921; moved to London, 1922-37; joined protest against O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars in columns of Irish Statesman, (letter of 20 Feb. 1926); met (and ‘married’) Nora Walker, in London, 1930 [‘pleasant, with my Nora, on a May morning to drive ...’] received Tailteann Award, 1932; issued The Bright Temptation (1932), a novel banned up to 1954; treated as an object of contempt among the ‘antiquarians’ in Beckett’s essay on ‘Recent Irish Poetry’ (Bookman, 1934); omitted from Yeats’s Oxford Book of Modern Verse (1936), and much hurt by it; |

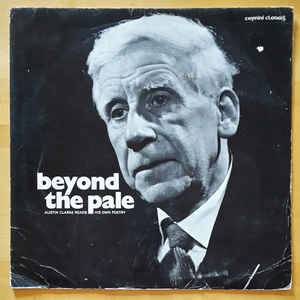

| issued Collected Poems (1936), intro. Padraic Colum; returned to Ireland with Walker, 1937; caricatured as Ticklepenny in Beckett’s Murphy (1938); settled at Bridge House, Templogue, with Walker; suffered second nervous breakdown; est. Dublin Verse-Speaking Soc. with Robert Farren, 1941 [var. 1944]; published under Bridge Press imprint from 1945; issued scathing review of Robert Lowell’s Poems 1938-1949 in The Irish Times (30 Sept. 1950); wrote Poetry in Modern Ireland (1951), in Cultural Relations Committee series - professing that his ‘own recent work’ was ‘inspired by the belief in the immediate needs [sic] for an Irish Welfare State’; reviewed Letters of Ezra Pound in The Bell (18, 2, 1952); after The Moment Next to Nothing (1953) endured 17 years of poetic silence, up to Ancient Lights (1955); established friendship with Liam Miller resulting in the publication of Too Great A Vine (1957) and other works in the Dolmen Press imprint designed by Miller; elected President of PEN; suffered heart attacks in 1959 and 1964; Garech Browne issued a record of Clarke reading his poems, as Beyond the Pale (Claddagh 1964) |

| issues Mnemosyne Lay in Dust (1966) first printed as “Loss of Memory” in Quarterly Review of Literature (1966) - recounting his mental breakdown of 1919 which resulted from the death of his father and his disasterous relationship with Cummins, Clarke himself appearing as Maurice Devane; read with Brendan Kennelly and Eavan Boland at the dedication of the Yeats Memorial, St. Stephen’s Green, 26 Oct. 1967; wrote The Impuritans (1971), ‘freely adapted’ from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Goodman Brown”; laid foundation stone of Lyric Players’ Theatre, Ridgeway St., Belfast; d. 19 March 1974; there is an oil portrait portrait by Estelle Solomons (1934), held in the Municipal Gallery, Dublin; reprint editions of the poems have been issued by W. J. McCormack (1991) and Dardis Clarke, his younger son (2008); Dardis (d.2013), a son, was sometime chairman of Eigse/Poetry Ireland, a life-member of the National Union of Journalists and a champion of his father’s poetry; Aidan Clarke [q.v.], his elder son, is the historian of the ‘Old English’ in Ireland; Clarke’s correspondence and sundry papers are held in the National Library of Ireland [NLI] as Collection List 83 - (MSS 38,651-38,708), compiled my Mary Shine Thompson [see infra]; UCD Library Special Collections holds 5,000 vols. previously in Clarke’s personal library and also hosts the Austen Clarke/Poetry Ireland Collection incorporating a listing and a digitised selection of his reviews [online]. NCBE IF DIB DIW DIH DIL FDA HAM OCIL |

[ top ]

|

Works

| Poetry |

|

| [ top ] |

| Novels |

|

| Plays [verse] |

|

| Plays [prose] |

|

| Autobiography |

|

| [ top ] |

| Miscellaneous [selected] |

|

Note: very many unsigned reviews by Clarke appeared in the Times Literary Supplement while he lived in London [see Gregory A. Schirmer, ed., Reviews and Essays (1995), infra]. |

| [ top ] |

| Collected & selected editions |

|

See also Robin Skelton, ed., Six Irish poets: Austin Clarke, Richard Kell, Thomas Kinsella, John Montague, Richard Murphy, Richard Weber (Dublin: Dolmen Press; London: OUP 1962), 134pp. [22cm.] |

| Discography |

|

|

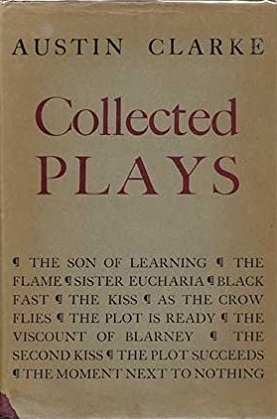

| Dolmen edition of the Collected Plays (1963) |

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Collected Poems (Dublin: Dolmen 1974), taken from Night and Morning (1938, 11pp.; Ancient Lights (1955), 11pp.; Too Great a Vine (1957), 13pp.; The Horse-Eaters (1960), 9pp.; Forget-me-not (1962), 9pp.; Flight to Africa, I, II, III, resp. 45, 16, 5pp.; Mnemosyne Lay in Dust (1966), 28pp.; Old Fashioned Pilgrimage (1967), 31pp.; The Echo at Coole (1968), 26pp.; A Sermon on Swift (1968), 26pp.; Orphide (1970), 24pp.; Tiresias (1971), 24pp.; The Wooing of Becfola (1974), 24pp. [see note.]Beyond the Pale: Austen Clarke Reads His own Poems (Claddagh 1966): Contents [Tracklist]: A Side: The Scholar; Night And Morning; The Envy Of Poor Lovers; The Blackbird Of Derrycairn; Mabel Kelly; Peggy Brown; Breedeen; The Abbey Theatre Fire; Irish-American Dignitary; The Flock At Dawn. B Side: Mount Parnassus; Over Wales; Burial Of An Irish President; Cypress Grove; Marriage; Japanese Print; Beyond The Pale. Notes.

Mary Shine Thompson, ed., Selected Plays of Austin Clarke (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 2001), 329pp. [The son of learning; The Flame; Black Fast; The Kiss; As the Crow Flies; The Viscount of Blarney; The Second Kiss; Liberty Lane; St Patrick’s Purgatory; The Frenzy of Sweeny. Note: incls. 2 unpub. plays].

Note: “The wooing of Becfola” appeared in Poem of the Month Club (1970-77), Third Folio.

|

| Beyond the Pale (Claddagh Records 1964) |

[ top ]

Criticism| 1934-79 |

|

| 1980-89 |

|

| 1990-99 |

|

| 2000- |

|

| See also .. |

|

| Bibliography |

|

| [ top ] |

Bibliographical details

John Montague, et al., A Tribute to Austin Clarke on His Seventieth Birthday (Dublin: Dolmen 1966), 27pp. CONTENTS: Thomas Kinsella, “Magnanimity” [poem] [7-8]; John Montague, untitled essay [8-10] and “Time Out“ [poem] [10-11]; Hugh MacDiarmuid, ‘Three Poems for Austin Clarke’ [poems] [11-12]; Serge Fauchereau, untitled essay in French [13-15]; Padraic Colum, untitled poem [15-16]; Ted Hughes, “Beech Tree” [poem] [16]; Richard Weber, “A Visit to Bridge House” [poem] [16-17]; Christopher Ricks, untitled essay [18-19]; Anthony Kerrigan, “Two Anniversaries” [poem] [20]; Denis Donoghue, ‘One More Brevity’ [20-22]; Charles Tomlinson, “The Poet in Antrim” [22-23]; Liam Miller, ‘The Books of Austin Clarke: A Checklist’ [23-27].

Maurice Harmon, ed., Irish University Review, ‘Austin Clarke Issue’, 4, 1 (Spring 1974). CONTENTS: Introduction [9]; Harmon, ‘Notes Towards a Biography’ [13]; Brendan Kennelly, ‘Austin Clarke and the Epic Poem’ [26]; Robert Welch, ‘Austin Clarke and the Gaelic Poetic Tradition’ [41]; Roger McHugh, ‘The Plays of Austin Clarke’ [52]; Tina Hunt Mahony, ‘The Dublin Verse-Speaking Society and the Lyric Theatre Company’ [65]; Clarke, ‘The Visitation: A Play’ [74]; Vivian Mercier, ‘Mortal Anguish, Mortal Pride: Austin Clarke’s Religious Lyrics’ [91]; Robert Garratt, ‘Austin Clarke in Transition’ [100]; Martin Dodsworth, ‘“Jingle-go-Jangle: Feeling and Expression in Austin Clarke’s Later Poetry’ [117]; Thomas Kinsella, ‘The Poetic Career of Austin Clarke’ [128]; Gerald Lyne, ‘Austin Clarke: A Bibliography’ [137-55].

R. Dardis Clarke, ed., Austin Clarke Remembered: Essays, Poems and Reminiscences to Mark the Centenary of His Birth (Dublin: Bridge House 1996). CONTENTS: R. Dardis Clarke, ‘Editor’s Note’ [7]; Seamus Heaney, ‘Introduction’ [9]; [q.author], review of The Veneance of Fionn, in Times Literary Supplement (17 Jan. 1918), [q.p.], [12]; Patricia Boylan, ‘’Darling Austin’ [18]; Lucy Collins, ‘Music in Mouth: Women and Language in the Poetry of Austin Clarke’ [22]; Aileen Dempsey, ‘The Cremation of an Irish Poet’ [34]; Michael Hartnett, ‘The Devil’s Advocaat’ [46]; Seamus Heaney, ‘The Yellow Bittern (from the Irish of Cathal Buí MacGiolla Gunna, c.1680-1756)’ [49]; Brendan Kennelly, ‘The House is Gone (for Austin Clarke)’ [51]; Thomas Kinsella, ‘Brothers in the Craft’ [52]; Thomas McCarthy, ‘The Poet on his High Bicycle’ [57]; Derek Mahon, ‘Shiver in Your Tenement’ [64]; Gus Martin, ‘ Clarke - A Life and Clarke - His Literary Legacy’ [66]; John Montague and Donncha O Corráin, ‘The Blameless Lecher’ [83]; George A. Schirmer, ‘Clarke as Critic’ [84]; Douglas Sealy, ‘Getting to Know Clarke’ [96]; Mary Thompson, ‘Austin Clarke and the Experience of Modernity 1912-1922’ [107]; Notes on Contributors [132-33].

(Dolmen Press 1983)

[ top ]

| Thomas Kinsella called the later poems ‘wickedly glittering narratives [...] poetry as pure entertainment, serious and successful’. (The Dual Tradition.) |

Samuel Beckett [as pseud. Andrew Belis], ‘Recent Irish Poetry’, in Bookman (Aug. 1934), pp. 235-36: ‘Mr Austin Clarke, having declared himself, in his Cattle-drive in Connaught (1925), a follower of “that most famous juggler, Mannanaun”, continues in The Pilgrimage (1920) to display the “trick of tongue or two” and to remove, by means of ingenious metrical operations, “the clapper from the bell of rhyme” [quotations 1 & 2 taken on Introduction to “Cattledrive” with vars.; quotation 3 taken from Commentary to “Pilgrimage”]. The fully licensed stock-in-trade from Aisling to Red Branch Bundling, is his to command. Here the need for formal justifications, more acute in Mr. Clarke than in Mr. Higgins, serves to screen the deeper need that must not be avowed.’ (rep. in Lace Curtain, No. 4, Summer 1971, pp. 58-63, and Disjecta, ed. Ruby Cohn, London: Calder 1983, pp.70-76; The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, Derry 1991, Vol. 3, p.246.) See also note on Beckett’s caricature of Clarke, infra.

W. R. Rodgers ed., Irish Literary Portraits (London: BBC 1972), p.72, records Clarke’s remark that ‘Yeats was rather like an enormous oak-tree, which, of course, kept us in the shade and of course we always hoped that in the end we could reach the sun, but the shadow of that great oak-tree is still there’.

Padraic Fallon, contemporary review of Collected Poems (Dublin: Dolmen Press 1974), in The Irish Times, ‘Book of the Day’ [q.d.], incls. the remarks: ‘I don’t know if he ever arrived at any kind of personal Deity but there was in him from the very first an almost frantic worship of landscape. … Once, confessing, he told me of the time in St. Albans, in south England, when he used, under the influence of AE’s Candle of Vision, wander the countryside seeking an actual illumination from things, aurae in trees and hedges, nymphs in the air above the streams. The world was alive to him in those times. And it was a life that never really died. I doubt if he would cut down a tree, even those that grew inward and left his study truly a green thought in a green shade. […] so much of his life belongs to this vital activity that it makes me unappreciative of this development as a satirist of modern idosyncrasy [sic]. God knows we need one in this sad scene. But the verse is definitely against the obvious witticism.’ Further: ‘I enumerate this list [of contents and pages] just to show the sudden almost unanticipated flowering of Clarke’s middle and late years. The quality is something which must still be determined, the last verse is delightfully expert, and unashamedly enjoys itself in metrical devices of a kind not usually put into service by any craftsman, even one as jubilant as Clarke. [… &c.]’.

[ top ]

Kate O’Brien, ‘UCD as I Forget It’, in University Review (Summer 1963), pp.6-11: ‘From Austin Clarke, shy, unhappy, I suspect, in his first job - form that rapidly muttering, fresh-minded and always-in-flight young lectuer, the attentive - of which on my own terms I became one - could get light, and direction. He said striking things, when one could hear them. He was amusing and rude about essays - but once he actually said out loud in class that in one of mine he found “the outward sign of inward grace.” I have not forgotten either my pleasure or astonishment.’ (p.10; for further extracts, see under O’Brien, supra .)

Thomas Kinsella on Austin Clarke: ‘his knife-glance curiously among us’ (Quoted by Kevin Kiely, reviewing Kinsella’s Collected Poems, in Books Ireland, March 2002, p.61.)

John Montague, ‘The Impact of International Modern Poetry on Irish Writing’ (1972) [speaks of ‘‘Kinsella’s success’ and the appearance of Irish poets in American-edited anthologies in the 1960s, especially Rosenthal who devoted a section to Irish poetry in his studyThe Poets]: ‘A climate had been created in which the rediscovery of Austin Clarke had almost become inevitable; in July 1959, I wrote in Poetry that his “general subject, Irish Catholicism and its emotional malformations, is no longer a local phenomenon, as modern American and Australian politics surely indicate. Technical interest is not lacking; Clarke’s adaptation of techniques from Gaelic verse to encompass the Irish Catholic subject parallels modern experiment elsewhere. A collected volume of his later work from “Pilgrimage” onwards, would, I think, reveal a talent as considerable as that of Tate, Ransom, or Muir.” / The rest is literary history, but the comedy of Mr Clarke, the most implacable opponent of modernism. in Ireland, being accepted, like Yeats, as a late recruit to international literature should not escape us. The argument was always a false one, since the terms are not exclusive, and the wider an Irishman’s experience, the more likely he is to understand his native country.’ (p.155; see full text, in RICORSO, Library, “Critical Classics”, infra.)

Tom MacIntyre, review of The Bright Temptation, Hibernia (1980), [q.p.]: ‘It’s nothing except Clarke on the subject of love in Ireland. This is a beautiful book. It is tender, witty, savage, sad, technically the author’s control of his material is complete ... published in 1932. Read it, brood on it, look down the 1966 road - and tell me, friend, if you heart is not badly shaken.’

[ top ]

Gregory A. Schirmer: ‘[“Mnemosyne” evolved] out of the same struggle with religious prohibition documented in “Pilgrimage” and “Night and Morning”, and has at its centre the same humanistic vision that informs Clarke’s work from beginning to end’. (The Poetry of Austin Clarke, Dolmen Press 1983, p.162).

Seán Lucy, ‘The Poetry of Austin Clarke’, in The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, 9, 1 (June 1983), pp.5-21: ‘Clarke’s Collected Poems (1974) takes us from romantic cultural nationalism to the synthesis of Irish Tradition and twentieth century modernism. [...] The influence of Yeats, Herbert Trench [Deirdre Wed], the Gaelic models, James Stephen’s Irish Fairy Tales, the Irish Middle Ages, and the pressures of living in a particular society, are discerned. Clarke showed a new generation of Irish poets how a true modern voice could emerge from their own tradition, a voice cabable of profound ironies and satire, as well as a new relaxation and a gentle pleasure of the sensual. Though his work is uneven, Clarke became a poety of wide emotional and technical range, a key figure in the development of Irish poetry in English.’ [Bilingual Summary; the article is available at JSTOR online.]

David Cairns & Shaun Richards, Writing Ireland: Colonialism, Nationalism and Culture (Manchester UP 1988), alludes to ‘Austin Ticklepenny - ‘The Olympian sot’ [in Murphy], where Clarke’s Pilgrimage, p.43, is parodied with further comments on his ‘prosodoturfy’ (Picador edn., p.53), such a specific mockery of Clarke that he was urged [by Gogarty] to bring a libel action against Beckett (p.136). [See further under Oliver St. John Gogarty, infra.)

[ top ]

Maurice Harmon, Austin Clarke, 1896-1974: A Critical Introduction (Dublin: Wolfhound 1989): ‘Assonance, more elaborate in Gaelic than in Spanish poetry, takes the clapper from the bell of rhyme […] by cross-rhymes or vowel rhyming, separately, one or more of the syllables of longer words, on or off accent, the difficulty may be turned: lovely and neglected words are advanced to the tonic place and divide their echoes.’ (p.19.); ‘[Clarke held that Irish poetry was] well in advance of contemporary English poetry both in its technique and its subtle range of consciousness’ (ibid., p.76.) [Cont.]

| Maurice Harmon (Austin Clarke [...] A Critical Introduction, 1989) - cont.: ‘It is Devane’s appalled encounter with mental breakdown [in “Mnemosyne Lay in the Dust”] and with cruel and degrading methods of treatment that the poem seeks to realise.’ (p.206.) Devane is tortured by the attendants, who feature as ‘shadowy figures’ and ‘assailants’; he forces himself to ‘Think!’, but ‘All was void’ until there returns memories of his love-relationship with Margaret, which ended when ‘Nightly restraint’ terminated ‘their romantic dream.’ Catholic guilt is now recognised as the fundamental cause of the character’s breakdown (idem.) [Cont.] |  |

Maurice Harmon (Austin Clarke [...] A Critical Introduction, 1989) - cont.: ‘Had Austin Clarke ceased to write in 1936, when he was forty years of age and had published Collected Poems, his reputation would not have been secure. Instead of becoming a significant modern poet, he would have been remembered as a poet in whose work the aims and emphases of the Irish Literary Revival had been prolonged and extended; he would have been remembered for a few poems which are of interest for their use of assonance and for a couple of poems which have more than ordinary intensity and control’. (p.247). Also: ‘[Clarke’s achievement is based] decisively on the acceptance of himself’ (Irish Poetry After Yeats, Dublin: Wolfhound 1997, p.17). |

[ top ]

John Hobbs, ‘Restoring Austin Clarke for Contemporaries’, review of Selected Poems, ed. Hugh Maxton, in Irish Literary Supplement (Fall 1992), p.24: ‘He had a talent for depicting spiritually desperate characters, yet as with the American poet Edwin Arlington Robinson, his careful art cannot transcend their depressions, so their controlled pathos may not move us as much as we feel it should. Witness even the melancholy tale of Clarke’s own early mental breakdown and hospitalization reflected in the long rambling poem “Mnemosyne Lay in the Dust”, usefully reprinted here in its entirely. Even the fine ironic portrait of “Martha Blake at Fifty-One,” sick until death in soul and body yet ignored by the Catholic Church, somehow lacks the intensity Clarke strives for. // Compared to his contemporary Patrick Kavanagh, for example, Clarke is often seen as a paradigm of the self-conscious artist obsessed with intricate patterns of neo-Celtic assonance. Unfortunately, many of his poems have the appearance of formality without its fierce pressure, because he evades rhyme, rhythm and poetic form more than he uses them. In his own words, his method “takes the clapper out of the bell of rhyme” (21) The contrast with Yeats’s artistry is unfair but inevitable. Who can read Clarke’s “‘The Young Woman of Beare” without recalling Crazy Jane? Yet Jane’s successor defies society in ten-line stanzas with this calm tone: I am the bright temptation / In talk, in wine, in sleep. / Although the clergy pray, / I triumph in a dream […] Maxton sees Clarke as “a taker of risks,” but those risks were less literary than personal and moral - for example, defending sexuality in a puritanical times - and they are bound to seem less consequential today than they were then. […] Maxton’s arrangement of the selections by themes - history, women, politics, theology, literature, and sexuality - rather than chronology has the advantage of drawing Clarke into the contemporary cultural debate in Ireland.’ Further, Hobbs reflects on Maxton’s editorial style, ‘With impressive learning and ingenuity the editor locates ironies and contradictions in the backgrounds rather than within the poems themselves, leaving their foregrounds relatively unexplored.’

Patrick Crotty, ed., Modern Irish Poetry (Belfast: Blackstaff 1995), Introduction: ‘[Clarke’s] increasing dependence on homophonic rhyme and other stylistic eccentricities suggests an almost wilful self-subversion on the part of a writer who knows his complaints will go unheard’; ‘[he] recuperated the intricate assonantal patterning of Gaelic verse in a recognisably modern form … and turned a potentially reactionary regard for the past to the service of a libertarian vision.’ (p.3; and see selection list, infra.)

Robert Greacen, review of Schirmer, Reviews and Essays (1995), in Books Ireland (Feb. 1996), p.19: gives 1929-37 as dates of Clarke’s sojourn in London and 1940 as date of foundation of Dublin Verse-Speaking Society; quotes Clarke on Yeats (‘that enormous oak-tree ... &c., as supra’); ‘the loss of Yeats and all that boundless activity, in a country where the mind is feared and avoided, leaves a silence which it is painful to contemplate’; also, ‘for serious attempts in criticism, we must turn to Cambridge, London, or Yale’; saw MacNeice as ‘an English intellectual’ whose philosophy derived from an ‘ineffectual Fabianism’.

Edna Longley, ‘Postcolonial versus European (and post-Ukanian Frameworks for Irish Literature’, in Irish Review, 25 (1999 / 2000): ‘a plangently isolationist tendency emerges in Clarke’s critical writing in the 1930s. Hence his dismissive reaction to MacNeice’s Autumn Journal: “Mr MacNeice is prepared, apparently, to plunge Europe into a catastrophic war to save the Czechs and other small nations, but becomes the complete moralist when it comes down to his own country and adopts the manner which we usually associate with the typical West Briton.” Even Clarke’s slanted précis decloses that MacNeice does not perceive Ireland’s failings (which include those of the North) as unique but as implicated in the wider questions that the Munich crisis raises about Europe, Britain and western civilisation. There is a naïve idea that, by not entering the war, mainly for complex internal reasons, the Free State left Europe, only to rejoin it in 1945 (here we go again!).’ (p.85; quoting Clarke, Dublin Magazine., 14, 3, July- Sept. 1939, pp.82-84.)

[ top ]

Gerry Smyth, Decolonisation and Criticism: The Construction of Irish Literature (London: Pluto Press 1998), p.187-88, commenting on Poetry in Modern Ireland (1951; rep. 1961): Austin Clarke [187] one of the dominant literary-affiliated intellectuals in the post-revolutionary era […] major poetic voice […] wide-ranging […] implying a readership already familiar with certain developments in Irish cultural and political history. At the same time, it is difficult to discover any informing argument or position in the text. […] the author appears to be playing the “grand old man” of Irish letters (although he was only fifty five, at the time of writing), relating a narrative from which he, as organiser and orchestrator, remains coolly aloof. [187]; It is not amenable to extraction, as there is hardly any passage in which the author sustains a critical point or risks any kind of judgement, subjective or scholarly. […] Refusing to invest subjectively in Irish cultural debate, Clarke the poet-critic attempts to step outside history […] fails to appreciate that such a manoeuvre can only take place in history and that in spite of its bland tone and apparently non-committed stance, Poetry in Modern Ireland in fact constituted a highly political intervention into the debate on decolonisation with which its subject matter - Irish Literary history - was already linked. […] The fact that, as one of Ireland’s more famous modern writers, he has been unproblematically recruited by the state, only compounds this interpretation. (p.188.)

David Wheatley, review of Neil Corcoran, Poets of Modern Ireland (Cardiff: Univ. of Wales Press [1999]), in Times Literary Supplement (25 Feb. 2000): ‘A thoughtful essay explores Austin Clarke’s “Memnosyne Lay in the Dust” , the long poem loosely inspired by Clarke’s experience of mental collapse and institutionalization in 1919. Though sections appeared in the 1930s, it was not until the poem had been morosely ruminated over by Clarke for almost three more decades that it was finally published in 1966. Clarke’s tortured attention to the ills of the priest-ridden Free State have threatened to reduce his reputation to that of a “local complainer” , self-defeatingly introspective and parochial. In one of his less divine caprices, [Paul] Muldoon omitted him entirely from his Faber Book of Contemporary Irish Verse. To ignore Clarke in this way, however, is a terrible mistake. As Corcoran’s sensitive reading helps to bring out, “Mnemosyne” is one of the central achievements in Irish poetry of the post-war period.’ (p.23.)

Maurice Harmon on “Ancient Lights” by Austin Clarke, in Irish University Review: A Journal of Irish Studies [Special Irish Poetry Issue, guest ed. Peter Denman] (Autumn 2009): ‘The publication of Ancient lights: Poems and Satires, First Series (1955), marked the beginning of a remarkable new period in the poetic career of Austin Clarke. Some people may have seen it corning in the poems he published in The Irish Times: “Mother and Child”, June 1954; “An Early Start”, August 1954, followed by two Poems in Irish Writing, “Fashion” and “The envy of poor lovers”, Autumn 1955. But it is unlikely that anyone could have anticipated the poetic surge that ensued: Too Great a Vine: Poems and Satires, Second Series (1957); The Horse-Eaters: Poems and Satires, Third Series (1960), all clearly connected as work in progress, with the same kind of material and the same subject matter dryly critical observations on Irish society, including defiant comments on the Catholic church - and all structured in the same way - a central, autobiographical poem surrounded by short poems, some satirical in manner. All three collections were characterized by a vigorous intelligence, exceptional linguistic energy, and a style packed with specific detail. That the poet was touching sixty in 1955 may not have been generally known, although many people would have associated him with the Irish Literary Revival and would have seen him as an enthusiastic imitator of its aims and methods: these included the use of Irish myth and legend, and writing in a style that was mystical and musical.’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Journals > IUR”, via index, or direct.)

[ top ]

Poetry

“The Lost Heifer”: ‘When the black herds of the rain were grazing / In the gap of the pure cold wind / And the watery hazes of the hazel / Brought her into my mind / I thought of the last honey by the water / That no hive can find [...]’. (Quoted in Robert Welch, ‘Irish Writing in English’, in Introduction English Studies, ed. Richard Bradford, London: Pearson Educ. 1996, p.665.)

| The Austin Clarke page at Poetry Archive containing his recordings of “The Blackbird of Derrycairn” and “Japanese Print” - both from Beyond the Pale (1964). [online] |

“‘Penal Law”: ‘Burn Ovid with the rest. Lovers will find / A hedge-school for themselves and learn by heart / All that the clergy banish from the mind / When hands are joined and heads bow in the dark.’ (Q. source.)

[Catholic Law:] ‘In their government cars, hiding / Around the corner ... ‘Tall hat in hand, dreading / Our Father in English, Better / Not hear that “which” for “who” / And risk eternal doom.’ (Poem on the funeral of Douglas Hyde, which Catholic ministers of state were prevented from attending by the canon law of the time.)

“Pilgrimage”: ‘When the far south glittered / Behind the grey beaded plains / And cloudier ships were bitted / Along the pale waves, / The showery breeze - that plies / A mile rom Ara - stood / And took our boat on sand / There by dim wells the women tied / A wish on thorn, while rainfall / Was quiet as the turning of books / In the holy schools at dawn.’ (From Pilgrimage and Other Poems; rep. Collected Poems, 1974, p.153).

“Mnemosyne Lay in the Dust” (1966): Beyond the rack of thought, he passed / From sleep to sleep. He was unbroken / Yet. Religion could not cast / Its multitudinous torn cloak / About him. Somewhere there was peace / That drew him towards the nothingness / Of all. He gave up, tried to cease / Himself, but delicately clinging / To this and that, life drew him back / To drip of water-torment, rack.’ [no source]; ‘Always in terror of Olympic doom, / He climbed, despite his will, the spiral steps / Outside a building to a cobwebbed upper room. / There bric-a-brac was in a jumble / His forehead was distending, ears were drumming / As in the gastric fevers of his childhood. / Despite his will, he climbed the steps, stumbling Where Mnemosyne lay in dust.’ (Quoted in Maurice Harmon, Austin Clarke, 1896-1974: A Critical Introduction, Dublin: Wolfhound Press 1989, p.74.)

[ top ]

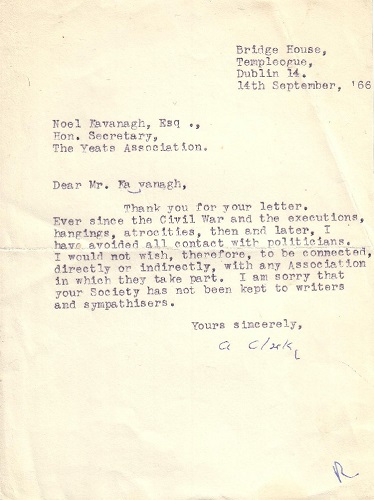

| [ See Austin Clarke’s letter to Noel Kavanagh of the Yeats Association, Sept. 1966 - expressing dislike of politicians - as attached ]. |

‘The Black Church’ [autobiographical essay]: ‘The poet, in fact, is in rather similar position to that of the creative artist who wishes to oppose the bad commercial traditions of ecclesiastical art […]. Harassed by the new religious journalism, which is destroying our imaginative traditions with hoarding and heading, poetry must rely on our earliest fears and intimations of immortality […]. Our novelists and dramatists write in anger but we must write in something like sorrow.’ (In Reviews and Essays of Austin Clarke, ed. Gregory A. Schirmer; quoted in Martin Mooney [review], Fortnight Review, Oct. 1996, p.35).

Twice Around the Black Church: Early Memories of Ireland and England (London: Routlege & Kegan Paul 1962): ‘At seven I made my first confession. I cannot remember how and when I was prepared for the sacrament of penance. No doubt I conned the penny catechism in class and learned the sixth commandment, which forbids all looks, words and actions against the virtue of chastity, speech with bad companions, improper dances, immodest company keeping and indecent conversation. In eager anticipation I set forth, proud of having now attained to the theological age of reason and in awe, knowing that the confessor was the visible representative of Christ. I went up Mountjoy Street that morning on our side of the street, past the Protestant orphanage, Wellington Street corner, and glanced up at the big clock over the public house. / In Berkeley Road chapel, I read the name of Father O’Callaghan over a confessional and, kneeling down, waited till the last penitents had left. Then I opened the side door on the left of the confessional and found myself in the narrow dark recess and, in a minute, the panel was drawn back. I told my little tale of fibs, disobedience and loss of temper and then Father O’Callaghan bent towards the grille and asked me a strange question which puzzled me for I could not understand it. He repeated the question and as I was still puzzled he proceeded to explain in detail and I was disturbed by a sense of evil. I denied everything but he did not believe me and, as I glanced up at the grille, his great hooknose and fierce eyes filled me with fear. Suddenly the panel closed and I heard Father O’Callaghan coming out of the confession box. He opened the side door and told me to follow him to the vestry. I did so, bewildered by what was happening. He sat down, told me to kneel and once more repeated over and over his strange question, asking me if I had ever made myself weak. The examination seemed to take hours though it must have been only a few minutes. At last, in fear and desperation, I admitted to the unknown sin. I left the church, feeling that I had told a lie in my first confession and returned home in tears but, with the instinct of childhood, said nothing about it to my mother.’ (pp.131-32; quoted in Brendan Kennelly, ‘Poetry and Violence’, in Åke Persson, ed., Journey into Joy: Selected Prose, Newcastle: Bloodaxe 1994, pp.36-37.)

Douglas Hyde: In The Young Douglas Hyde (IUP 1974), Dominic Daly quotes Austin Clarke’s remarks on Hyde as a teacher ‘[A]s he unwound an imaginary straw rope at the end of the play, [he] found himself outside the lecture room’ (‘On Learning Irish’, in The Irish Times, 10 April 1943 - and note that the same remark is attributed to Austin Clarke’s Twice Around the Black Church (1962) in P. J. Kavanagh, Voices in Ireland (1994), p.72.

Sean O’Casey: Clarke joined the protest against O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars in columns of Irish Statesman (‘several writers of the new Irish school believe that [his] work is crude exploitation of our poorer people in an Anglo-Irish tradition that is now moribund’ (20 Feb. 1926).

[ top ]

James Joyce (1): ‘ Some weeks later as we were sitting in a cheap café in a side street under the shadow of St Sulpice, drinking Pernod Fils, Joyce afer long silence, mentioned Yeats again. His remark was so surprising that I keep it in Italian: “La poesia de Mangan e de Yeats è quella segatora di chi sela da fa solo”.’ Clarke goes on: ‘He emphasised their obsession with hands, quoting Mangan and pointing to the frequency with which Yeats refers to pearl-pale hands. I realised that he was only acquainted with the early twilight poems. As I glanced at the drooping figure, I wondered if he had been addicted in youth to our national vice.’ (Penny in the Clouds 1968, p.96; quoted in Peter Costello, James Joyce: The Years of Growth, 1992, p.16.)

James Joyce (2): See Edna O’Brien, James Joyce (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1999): ‘Austin Clarke, a Dublin poet, said many years later when they met in Paris, that Joyce was eager to hear the latest smutty stories circulated among Dublin schoolboys. Clarke thought Joyce was afflicted “with a particular kind of Irish pornography”, but that he was also a dreamer.’ (p.102; no ref.)

‘A Centenary Celebration’: Clarke recounts meeting celebrating the centenary of Thomas Davis, scheduled for TCD but held on 20 Nov. 1914 in Antient Concert Rooms, at which Pearse and Yeats were confronted by Thomas Kettle, in uniform, and ‘fortified’ for the encounter [with drink]; quotes with approbation Pearse’s ‘closely reasoned’ words: ‘One loves the freedom of men because one loves men. There is therefore a deep humanism in every true Nationalist. There was a deep humanism in Tone and there was a deep humanism in Davis’. Clarke narrates the heckling of Kettle’s address from the floor by a man who looks like Darrell Figgis, and the speaker’s reply, ‘where was your father when mine was in prison’; Clarke speaks of the illogical fact that ‘a fine poet should come there to speak about Thomas Davis in the uniform of the British’ and felt with the shouters; ‘Captain Kettle gave up the unequal struggle for freedom of speech’; Yeats restored the audience to humour with a reference to the execrated Neitsche; Clarke concludes that ‘my sudden suspicion that Yeats had captured cleverly that small audience of rebels proved right’ when he reads the newspaper placards, ‘Dublin audience cheers Neitszche’. ‘A Centenary Celebration’, in Robin Skelton and David R. Clark, eds., Irish Renaissance [A Gathering of Essays, Memoirs, and Letters from the Massachusetts Review] (Dublin: Dolmen Press 1965), pp.90-93; p.93.

| Clarke’s Letter to the Yeats Association (1966) | |

|

|

|

[ Click her to view in a separate window. ]

[ top ]

References

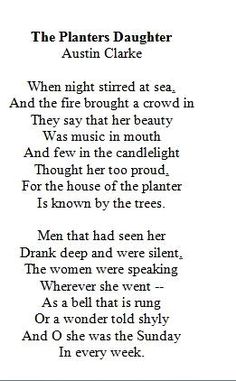

Grattan Freyer, Modern Irish Writing (1979), includes poems by Austin Clarke [‘The Envy of Poor Povers’ ‘The Straying Student’; ‘The Medical Missionaries of Mary’; ‘The Thorn’; ‘Martha Blake’]; Maurice Harmon, ed., Irish Poetry After Yeats: Seven Poets (Wolfhound Press 1979), includes long extract from ‘Mnemosyne Lay in the Dust’ and selection; Patrick Crotty, Modern Irish Poetry (Belfast: Blackstaff 1995), The Lost Heifer; The Young Woman of Beare (extract); The Planter’s Daughter; Celibacy; Martha Blake; The Straying Student; Penal Law; St. Christopher; Early Unfinished Sketch; Martha Blake at Fifty One; Tiresias II (extract).

D. E. S. Maxwell, Modern Irish Drama (1984) lists The Son of Learning, The Flame, The Viscount of Blarney, The Second Kiss, The Plot Succeeds, The Moment Next to Nothing, in Collected Plays (Dublin 1963); also The Son of Learning (London 1927), renamed The Hunger Demon; The Flame (1930); Sister Eucharia (1939); The Viscount of Blarney (1944); Collected Poems (Dolmen 1974). Bibl., S. Halpern , Austin Clarke: His Life and Works (Dublin: Dolmen 1975) [but 1974 in A. C. Patridge, Language & Society in Anglo-Irish Lit, 1984, bibl., p.364)]. NOTE, Maxwell gives the following account of the Clarke’s verse drama (in Modern Irish Drama, 1984), To re-animate the work begun by Yeats, [Austin Clarke] with his fellow-poet Robert Farren founded the DVSS in 1940. Up to 1953 it gave frequent performances of dramatic poems - by Browning, Chesterton, Vachel Lindsay - on Radio Éireann; and between 1941 and 1943 presented three season of verse plays, mainly by Clarke and Bottomley, at the Peacock. In 1944 he founded the Lyric Theatre Company entirely for stage performances. Without its own theatre or regular company, it presented bi-annual evenings at the Abbey until 1951 when the Abbey burnt down. Of 26 plays put on by the Lyric, nine were by Clarke, two repeated. The company also revived Fitzmaurice and gave plays by Yeats - incl. first performances of The Death of Cuchulain and The Herne’s Egg - T. S. Eliot’s Sweeney Agonistes, Laurence Binyon’s Brief Candles, and Donagh MacDonagh’s Happy as Larry. // ... it stimulated no revival beyond itself ... a revivalist fusty air ... with no generative power of its own ... [pp.140-41; plot summaries, ibid., pp.141-45].

Austin Clarke - Papers in the National Library of Ireland - Collection Lists No.83 - (MSS 38,651-38,708; Accession No.5615)

compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson (2003)Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Correspondence- Letters to Clarke: Names known to Ricorso incl. George Russell, J.O. Bartley, John Betjeman, Gordon Bottomly, Nicola Gordon Bowe, Brian Boydell, Garech Brown, George Buchanan, Hubert and Peggy Butler, Joseph Campbell, David H. Charles (sol.), Richard Church, Padraic Colum, Maurice Craig, Leslie Daiken, Aodh de Blacan, Alan Denson, Dolmen Press, Padraic Fallon, Robert Farren, Seamus Heaney, FR Higgins, Lord and Lady Longford, Derek Mahon, Vivian Mercierr, Ewart Milne, John Montague, George Moore, Hugh MacDiarmid, Donagh MacDonagh, Brendan McGann, Sean O’Casey, Sean O’Faolain, Meta O’Flaherty, Joseph O’Neill, Mary Devenport O’Neill, Seumas O’Sullivan, Herbet Palmer, W. R. Rodgers, Blanaid Salked, Philip Sayer, William Kean Seymore, Shiela Steen, R. S. Thomas, Richard Weber, Yeats family and relating to Yeats [and num. al.]. Publishers listed include Arena, Ariel, BBC, British Council, Cahill and Co., Curtis Brown, Decca Record Co., Irish Press, Irish Times, Observer, Oxford Univ. Press, Radio Eireann, Routledge and Kegan Paul, Times and Times Lit. Supp. [TLS], William & Norgate. Letters from Clarke [pp.118-124; recipients unlisted.] Correspondence - Letters from Clarke (pp.118-23) - incl. those addressed to Mr Adams, Mr [?Jeremy] Addis, Seamus Breathnach (with broadcast TS attached), Buckley, Hubert Butler, Garech De Brún, Terence De Vere White, Dublin County Council Grants Department, Mr Figgis, Bob [probably Robert Farren], Robin [Flower], Susan Halpern, Blanaid Irvine, Derry [A Norman Jeffares], Mr Mac an Gille, Mr Kieran McInally Solicitor, Mr David Marcus, Liam Miller, Mr O’Flaherty, Mr O’Neill, Revenue Commissioners [Mr Kerrigan], Michael Smith, various unidentified addressees, c58 pp. —Available at National Library of Ireland - online as .pdf; accessed 27.10.2023.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, selects The Bright Temptation [1148-54], with Notes at 563 [Sons of Learning, play rejected by Abbey in 1927]; 723 [Clarke perhaps best understood, with others, as reacting against fervent pieties of earlier writers], 781 [bibl., Seamus O’Sullivan]; 1025-26 [chose medieval Ireland as site of his 3 hist. novels; [B]y introduction of invented and mythic personages, viz, the Prumpolaun, Sile na gCich, and of nightmare landscapes, viz., Glen Bolcan, enacting shrewd parallel betweeen medieval and modern Ireland [in] social satire similar to Stephens and O’Duffy]. There is no BIOG or cross-reference in Prose Fiction section of FDA2, but see FDA3 168, BIOG,and infra.]

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3, selects poems from The Cattledrive in Connaught; Pilgrimage and Other Poems; Night and Morning; Ancient Lights; Flight to Africa; Mnemosyne Lay in Dust; Orphide and Other Poems; A Penny in the Clouds (1968, Chaps. 1-4, including acquaintance with Thomas MacDonagh, Stephen McKenna and others.] with references and remarks; see especially Terence Brown, ‘The Counter Revival in Poetry’, includes comments on Clarke’s Celticism and his reaction against the Censorship Act [‘Clarke’s version of the Celtic-Romanesque is of a period authenticated by scholarship. where Yeats’s Celticism partakes fully of myth, Clarke’s myth of the Celtic-romanesque is involved significantly with history. Accordingly, the past in Clarke’s work is not a heroic ideal ... but a social norm ... It is the classic society of a Celtic-Romanesque Ireland and its humane attitudes to creativity and the sexual impulse that Clarke especially admired ... however his own psyche had been disturbed by the darker energies of modern Irish Puritanism’ [129-130]; note also, his sources for the high period of Irish Christianity in the Middle Ages were George T Stokes, Ireland and the Celtic Church (1886) and Margaret Stokes, Early Christian Art in Ireland (1887).

Manchester Library holds a cutting inserted as loose material in the front cover of Old-fashioned pilgrimage and other poems (Dolmen 1967) by from Austin Clarke, being an article entitled “Order in Donnybrook Fair” by John Montague about Irish poetry including the work of Clarke, published in Times Literary Supplement (17 March 1972). [See at JISC - online; accessed 27.10.2023].

[ top ]

Anthologies & Booksellers

Patrick Crotty, ed., Modern Irish Poetry: An Anthology (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1995), selects “The Lost Heifer” [13]; from “The Young Woman of Beare” [14]; “The Planter’s Daughter” [16]; “Celibacy” [17]; “Martha Blake” [18]; “The Straying Student” [20]; “Penal Law” [21]; “St Christopher” [21]; “Early Unfinished Sketch” [21]; “Martha Blake at Fifty-one” [22]; from “Tiresias II” [27].

Booksellers: HIBERNIA BOOKS (1996) lists ‘The Wooing of Becfola’, Poem of the Month Club [signed broadsheet] (1973); John Hewitt, ‘Austin Clarke’, in Threshold, No. 25 (Summer 1974); G. Schirmer, Reviews and Essays (Colin Smythe 1995). CATHACH BOOKS (1996-97) lists [[Old-fashioned] Pilgrimage and Other Poems (Allen & Unwin 1929)

[ top ]

Notes

W. B. Yeats: Yeats wrote to Olivia Shakespear, asking for a view of The Bright Temptation: ‘Read it and tell me should I make him an Academician. I find it difficult to see, with impartial eyes, these Irish writers who are as it were part of my propaganda.’ (Wade, ed., Letters, p.795; cited in Robert Garratt, Modern Irish Poetry, Tradition and Continuity from Yeats to Heaney, 1986, p.47.)

W. Yeats: Clarke wrote of Yeats, ‘In England the sheer art of [his] poetry has proved a useful influence and has schooled even the best known of the younger modernists. In Ireland, where the artistic tradition of the literary revival has not been broken, it has an imaginative incitement and great example rather than an influence ...English critics have tried to claim him for their tradition but, heard closely, his later music has that tremulous lyrical undertone which can be found in the Anglo-Irish eloquence of the eighteenth century.’ (‘Poet and Artist’, in The Arrow, Summer 1939; quoted in Roy Foster, ‘When the Newspapers Have Forgotten Me ...’, in Yeats Annual 12, 1996, p.168.)

Further: ‘He spoke to me at length of Donne, Vaugha, Herbert, Dryden and then of Landor, his voice rising and falling as he urged me to study their works and follow their austere example. As I was a lecturer in English literature at the time in University College, Dublin, and still immersed in Gaelic mythology and poetry, his severe lecture chilled me and, like Joyce, I felt that I had met him a generation too late.’ (Reviews and Essays of Austin Clarke, ed. Gregory A. Schirmer; cited by Martin Mooney, Fortnight Review, Oct. 1996, p.35).

Further: ‘[Yeats’s] later poetry celebrate[s] mournfully the passing of greatness. In his ranging themes he sums up an era and for us his language seems to bring to a poetic and glorious end the tradition of Anglo-Irish eloquence, for it has the vibrant timbre which can be heard in Burke’s prose […] and in tht last speech by Grattan in the Irish House of Commons before the Act of Union.’ (Poetry in Modern Ireland, p.49.)

Note: Clarke wrote a comment in The Irish Book Lover’s “Notes and Queries” column (Irish Book Lover, Vol. XXXI, No. 6 (Nov. 1951), suggesting that Yeats’s poem “Down by the Sally Gardens” was a ‘version’ of the rendering of a Leinster folk song made by P. J. McCall. (See further under McCall - infra.)

Out/Not In: Clarke was excluded from Yeats’s ed. of The Oxford Book of Modern Verse althought it was Yeats who first excited his interest in poetry (viz., ‘All the dear mummocks out of Tara / That turned by head at seventeen’: Flight from Africa).

Lady Gregory: verses prompted by a visit to Coole Park, ‘How Lady Gregory would drive twelves miles, / Day after day ... through the seven woods, / To count the Swans for Willie.’ (Cited by Robert Mahony in review of McDiarmid and Waters, eds., Selected Writings of Lady Gregory, 1995; in Irish Literary Supplement, p.23.)

Celtic Twilight: Clarke writes of ‘the shadowy world of subdued speech and nuance’ that was the heyday of the Celtic Twilight (Poetry in Modern Ireland, Dolmen 1951; 2nd edn. 1961, p.16; see Dominic Daly, The Young Douglas Hyde, 1974, p.133.)

[ top ]

Samuel Beckett included a caricature of Clarke as ‘a distinguished indigent drunken Irish bard’ or ‘pot poet’ in Murphy (1938) - ,viz., ‘This view of the matter will not seem strange to anyone familiar with the class of poetaster that Ticklepenny felt it his duty to Erin to compose, as free as a canary in the fifth root (a cruel sacrifice, for Ticklepenny hiccuped in bad rhymes) and at the caesura as hard and fast as his own divine flatus and otherwise bulging with as many minor beauties from the gaelic prosodoturfy as could be sucked out of a mug of Beamish’s porter. No wonder he felt a new man washing the bottles and emptying the slops of the better-class mentally deranged.’ (Murphy, p.53; quoted in Richard Kearney, Myth and Motherland [Field Day pamphlets, No. 5], Derry: Field Day Co. 1984, p.16, and more extensively in Declan Kiberd, Inventing Ireland: the Literature of the Modern Nation, Jonathan Cape 1995, p.532.)

Lyric Theatre Belfast, Programme for the Laying of the Foundation Stone at Ridgeway St., by Austin Clarke, 12 June 1965; includes poems by Padraic Colum, Seamus Heaney, John Hewitt [incl. poem for Mary O’Malley], Thomas Kinsella, Roy McFadden [‘Synge in Paris’].

[ top ]

Mnemosyne: There is a poem “Mnemosyne” by American poet Trumbull Stickney, a Swiss-born classical scholar: ‘It’s autumn in the country I remember. // How warm a wind blew here about the ways! / And shadows on the hillside lay to slumber / During the long sun-sweetened summer-days. / It’s cold abroad the country I remember. / The swallows veering skimmed the golden grain / At midday with a wing aslant and limber; / And yellow cattle browsed upon the plain. [...]’ (See —See “The Poets’ Corner” on The Other Pages - online [accessed 24.09.2010].

| Dardis Clarke - obituary (Irish Times, 13 March 2013) |

|

|

| Austin Clarke [R] with Ernest Blythe [L] and Brendan Kennelly [C] in 1970 |

Namesake: Austin Clarke (1934- ) is a West Indian poet, playwright, story-writer and author of non-fiction, born in the Barbados, and afterwards a Canadian citizen. The British Council’s writers’ page gives details:

‘[...] From 1974-75 he was cultural attaché to the Barbadian Embassy in Washington, after which he was asked to return to Barbados as General Manager of the Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation and adviser to the Prime Minister. He left after one year, returning to Canada, and later wrote Prime Minister, a novel inspired by this experience - an expose about corruption in a developing country. Returning to Canada, he wrote a weekly column for a Barbadian newspaper from 1979-1982, and served on the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada from 1988-1993. / Being a Canadian writer, born and raised in Barbados, allows Clarke to write from a unique perspective. [...]’ (See British Council notice - online; accessed 27.20.2023.)

[ top ]