| Life |

| 1882-1975 [orig. reg. as George De Valero; shortly revised to Edward de Valera]; b. 14 Oct. 1882, in Manhattan, New York; son of Catherine (‘Kate’) Coll [later Mrs Wheelwright], Knockmore, Bruree, and Vivion Juan de Valera, the couple having supposedly been married in St Patrick’s, Greenville, NY [no record existing]; registered as George, and christened as Edward (after a maternal uncle); sent by his mother, [supposedly] widowed, to be raised in Clare; enrolled in Bruree National School as Edward Coll, after the paternal uncle chiefly concerned in raising him; learnt patriotism from Land League priest Fr. Eugene Sheehy; learnt of his mother’s [re]marriage to Charles E. Wheelwright, an Englishman and groom to a Rochester family, NY; ed. CBS, Charleville (Rath Luirc), and Holy Ghost Fathers, Blackrock, Co. Dublin; appt. Professor of Maths, Rockwell, 1903; undistinguished mathematics grad. Royal University, 1904; teaches at Belvedere College, Dublin; appt. Prof. of Maths, Carysfort TTC, 1906; holds part-time app. at Maynooth and various Dublin colleges; experiences third rejection for priesthood (reasons unknown); joins Gaelic League Ard-Craobh, 1908; meets Janie [Sinéad] Flanagan [Ní Fhlannagáin], his Irish teacher, and m. Ní Fhlannagáin, 1910; settles at 23 Morehampton Terrace; |

| attends Volunteer meeting, Rotunda 25 Nov. 1913; captain of Donnybrook Company; Comm. 3rd Batt.; received orders as Captain of Company E of the Dublin Brigade to meet Asgard the, disembarking guns at Howth, July 1914 [var. June; vide Mary C. Bromage, 1956]; Adj. of Dublin Brigade; joins IRB; acted as Commandant of Boland’s Mill garrison in the Rising [‘if the people had only come out, even with knives and forks …’], and the last unit to surrender (now believed to have suffered nervous breakdown); imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol [“Convict 95” of ballad fame] and not tried till 8 May, purportedly in view of his American nationality, and reprieved in view of growing international objections to executions; held in Dartmoor, Maidstone, and Lewes prisons; released June 1917; advocates re-organisation of Sinn Féin on constituency basis; contests and won East Clare against IPP Patrick Lynch; President of new Sinn Féin at convention, Oct. 1917; arrested May 1918 in Sinn Féin anti-conscription campaign; 73 Sinn Féin seats won with 45 candidates in prison at General Election, Dec. 1918; Govt. of Republic established by Dáil Éireann, meeting in Mansion House, 21 Jan 1919; |

| escapes Lincoln Jail, elected President of the Irish Republic, 1 April 1919; appointed Irish government; travels to America, June 1919 returning 29 Dec. 1920 [18 months]; announces at press conference that Ulster Protestants who did not accept the Republic should ‘go back’ to Britain (and heard by St. John Ervine); met Devoy, but selects Edward L. Doheny, millionaire nephew of Michael Doheny, to lead American Committee for Relief in Ireland; made honorary chief by Chippewa tribe; chiefly stayed at the Waldorf Astoria; of purported $5 million collected, much remained in De Valera’s keeping occasioning controversy at home and in America; King George announces policy of conciliation to end Anglo-Irish war, 22 Jan. 1921; visited by Lord Derby, April 1921; meeting with Sir James Craig in Dublin, May 1921; Chancellor of NUI; elected MP, Co. Down under the provisions of the Govt. of Ireland Act, being one of 12 nationalist, of which 6 Sinn Féin, candidates to win seats, all of which were left vacant; deemed to be elected to Co. Down seat in Dáil Éireann in southern elections ensuing 5 days after; Truce between IRA and British forces in Ireland, 11 July 1921; authorises negotiations by plenipotentiaries in London, viz., Griffith, Collins, MacNeill, Childers, et al. - the lastnamed sometimes being considered his particular agent at the talks; sides with Cathal Brugha and Austin Stack against the Treaty; |

| re-elected President of Dáil on reconvening, Aug. 1921; authors an alternative to Treaty (Document No. 2) based on concept of ‘External Association’ with the Commonwealth, developed in an attempt to accommodate separate Irish stateship with monarchical status but without prejudice to Republican unity, proposed at private Dáil session, 14 Dec. 1921; Dáil debate on Treaty, at UCD, 14-22 Dec. 1921, adjourning for Christmas recess, and resuming 4-7th Jan.; de Valera formally gave notice that he would move the Document as an amendment to the Treaty, 4 Jan., 1922; ‘I stand as a symbol for the Republic […] I didn’t go to London because I wished to keep that symbol of the Republic pure even from insinuation, or even a word across the table that would give away the Republic’ (Treaty Debate, 4 Jan.); makes final speech in the debate, 6 Jan. repudiating attacks on his Irishness (‘I was reared in a labourer’s cottage here in Ireland’) and pronouncing the Dáil effectually extinct (‘this body has become completely, irrevocably split’); Treaty terms approved by 7 votes in house of 122 TDs (64 for, 57 against), resulting in majority ratification, 7 Jan. 1922 with de Valera and his followers retiring; Provisional Govt. established with Griffith as President; occupation of Four Courts by Rory O’Connor and others, 13 April 1922; |

| Four Courts bombarded by Free State forces, bombardment inaugurating Civil War, 28 June 1922; speaks out for war (‘… wade through rivers of blood’); de Valera enters election pact with Collins, May 1922; called on by Republicans to form emergency government; announced reorganisation of Sinn Féin, Jan. 1922; wrote to Liam Lynch, ‘we can best serve the nation at this moment by trying to get the constitutional way adopted’, 7 Feb. 1923; arrested at election meeting, Ennis, Co. Clare, amidst gunfire and confusion, 15 August; imprisoned at Arbour Hill, and much strengthened in his political resolve by the experience; returned for [East] Clare, 27 Aug. 1923; issues orders to ‘Rearguard of the Republic’ terminating hostilities (‘Military victory must be allowed to rest for the moment with those who have destroyed the Republic’); seeks to modify abstentionist policy, Dec. 1925; addresses Republicans at Wolfe Tone’s grave, Bodenstown, 25 June 1925; announces preparedness to enter Dáil Eireann if there were no oath, Jan. 1926; forms Fianna Fáil party, April 1926, presiding over the party to 1959; compares Republicans who accept oath to French monarchists who acquiesced in the ‘de facto controlling power’ of their parliamentary opponents through ‘prescription and the lapse of time’; Fianna Fáil wins 44 seats in June 1927, and enters Dáil; de Valera prevaricates over oath, which he signs ‘as a formality’ [var. ‘an empty formula’]; |

| supported the Mayo County Council in their refusal to appoint a Protestant librarian, Miss Dunbar Harrison (TCD), in Castlebar, 1930, arguing that the post concerned Catholic education; fnd. the Irish Press, 1931, ed. Frank Gallagher; won 72 seats in Gen. Election, defeating Cumann na nGaedhael, and forms first Fianna Fail Govt., Feb. 1932; serves as President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State and Min. for External Affairs; sets free republican prisoners and removes Cosgrave’s security legislation; maintains secret contact with IRA army council; officiates at Eucharistic Congress, attended by a million Catholics, effectively healing the rift between Fianna Fáil and the Catholic Church; President of the Council of the League of Nations, Geneva, 1932; conducts Economic War with Britain, withholding land annuities of £5 million in respect from the British Exchequer, 1932-38, causing damaging reprisals at British customs posts; elected RIA, 1933; James MacNeill’s post as Gov. Gen. terminated on his advice, and Domhnall Ua Buchalla appt. ‘Senascal’; becomes MP for South Down when Fianna Fáil wins 77 seats in general election, 24 Jan. 1933; |

| remained in power, 1933-37; establishes voluntary militia; supports with Cardinal McRory and others Fr. Peter Conefrey’s campaign and meeting against Jazz at Mohill, Jan. 1934, and supports Public Dance Halls Act, 1935; declares the IRA illegal, 1936; new Constitution underwriting ‘special position’ of Catholic Church as ‘the guardian of the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens’ (Art. 44), architected by de Valera himself in extensive correspondence with Archbishop McQuaid and Edward Cahill, SJ, and substantially composed by John Hearne, barrister and Legal Adviser to the Dept. of External Affair; institutes the office of President of Ireland, first held by Douglas Hyde; guarantees special position of the Catholic Church; incls. articles claiming island of Ireland as the state territory; also an article (41) on Family effectively militate against women working in official posts or generally outside the home; his Constitution narrowly ratified by the Dáil, 1937; |

| Taoiseach and Min. for External Affairs; Anglo-Irish agreement securing Treaty ports, 1938; 19th President of Assembly of League, Sept. 1938; declares for neutrality in the event of a Second World War, 19 Feb., 1939; made celebrated St Patrick’s Day Radio Éireann broadcast in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Gaelic league while articulating his pastoral version of the national dream; denounced the earliest newspaper reports of Holocaust atrocities by the Nazis in Bergen-Belsen as ‘anti-national propaganda’ on the part of British interests; visited German Ambassador (Herr Edouard Hempel) and signed the book of condolences at Germany Embassy, Dublin, on death of Adolf Hitler; ousted from Government by John A. Costello and Coalition, 1948; went on tour of USA, promoting anti-partition politics; visited India, 1948; out of government when Costello declared the Republic, 1948 (estab. March 1949); reprehends the declaration as an obstacle to unity (viz., ‘external association’); returns to government, 1951; retina trouble occurring from 1930s ending with peripheral vision only in 1952; defeated 1954; |

|

returns to power, Taoiseach, 1957; elected President of Ireland, 17 June 1959; attends premier of Mise Eire (dir. George Morrison, 1959); awarded DSc. by TCD, 11 March 1960, and in 1963 he ‘turned the sod’ to start the building of TCD’s New Library, designed by Paul Koralek; speaks at opening of RTÉ (‘like atomic energy, it can be used for incalculable good but it can also do irreparable harm’), 1962; re-elected 1966, defeating Tom O’Higgins by 10,000; visited by Jacqueline Kennedy, then staying with her children at Woodstown Hse., Co. Waterford, June 1967; received Order of Christ from Pope John XXIII; FRS, 1968; addresses Joint Session of Congress, Washington, 1964; retires, June 1973; d. 11.55 p.m. on 29 Aug. 1975, in Linden Convalescent Home, Blackrock; bur. Glasnevin; bequeathed £2,800 in his will and bestowed ownership of The Irish Press to his descendants; an obituary notice by J. L. Synge (nephew of J.M. Synge) appeared in Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society; his papers were deposited in the Franciscan Library, Killiney; the entry in the RIA Dictionary Irish Biography is by Ronan Fanning. DIB DIH FDA OCIL |

| [ top ] |

|

| President Eamon de Valera (Britannica) |

An extensive gallery of images and portraits of de Valera can be found |

Works

Maurice Moynihan, ed., Speeches and Statements of Eamon de Valera 1917-73 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1980).

[ top ]

| Criticism |

|

|

| [ top ] |

| General studies |

|

Dev on Stage: Tom McIntyre’s burlesque novel The Charollais (1969) figures de Valera as ‘Dee La Veera’; Gerry Gallivan’s play Dev (Dublin: Co-Op Books 1978, 76pp.) was first performed at Project Arts Centre in 1977.

[ top ]

Commentary

Lord Longford & Sir John Wheeler-Bennett, eds., The History Makers, Leaders and Statesmen of the 20th Century; chronologies [by] Christine Nicholls (London: Sidgwick & Jackson 1973), 448pp, ills. [Contents incl. Clemenceau to Nasser, the essay on Lloyd George being by APJ Taylor]. DE VALERA, by Wheeler-Bennett, pp.270-87, ed. b. 14 Oct.; Blackrock Intermediate College; UCD; NUI, and TCD [sic; other errs. incl. Dail Eirann [sic]; fnd. Fianna Fail, 1926; won general election, 1932; establish republic in 1936 [sic err] Constitution, on abdication of King Ed. VIII; author regards his father Vivion de Valera as Spanish from Basque country, or Cuba, or South America; m. Janie Flanagan, among his Gaelic League teachers, 1910; author calls Pearse ‘a mystic, a poet, a schoolmaster - and perhaps almost a saint - with a passionate idealism dedicated to Ireland and her people’ [276]. (Cont.)

Longford & Wheeler-Bennett (The History Makers [.... &c.] 1973) - cont.: Churchill is quoted as saying that the shot at Sarajevo ‘cut through the clamour of the haggard, squalid, tragic Irish quarrel which threatened to divide the British nation into two hostile camps’ [no ref.]; author speaks of rumours of Germany aiming to support ‘the forces of Sinn Féin’ in 1916; de Valera at East Clare election: ‘There are only two courses Irishmen can follow with a certain amount of logic […] the Unionists of the North are consistent in their desire to remain part of the British Empire; the only other position is the Sinn Féin position, completely independent and separate from England. How can they have conciliation?’ (Irish Times, 6 July

de Valera imprisoned in Lincoln Jail, May 1918; escapes; undertakes American tour, not received by President Wilson in USA, but raised £6,000,000 [note that Am. Fed. of Labour recognised Irish Republic on 17 June 1919]; arrested 22 June 1921 during raid by Royal Worcestershire Regt. on Dublin house; [author speaks here of his own ‘sheer intellectual inability as well as space’ in not detailing the treaty handled brilliantly by Longford in Peace by Ordeal].

de Valera did not admit inconsistency of Republic with Monarchy; ‘external association’ versus ‘Hungaria solution’; Dáil session that ratified the Treaty sat in UCD buildings, 14 Dec. to 7 Jan. 1922; 64/57 against; new constitution […] established a Republic of Ireland [sic]; Anglo-Irish Agreement with Chamberlain, 22 April 1938; [note that at the final meeting, Chamberlain handed to de Valera the field-glasses which had been taken from him at his capture by Capt. Hintzer at Boland’s Mill 22 years earlier]; anti-Partition remained ‘an act of faith’ […] to British representatives it was a permanent Banquo’s ghost at every meeting; people of Ireland regarded themselves as automatically neutral in 1939.

Author ends by citing a moderate analysis of de Valera’s his standing as being less an international giant than a great Irishman who has made a unique contribution to the liberty of his fellow-countrymen; ends: ‘a strange amalgam of dark mysticism, real-politik, and statesmanship; when one is in the presence his eyes, though sightless, seem nevertheless to penetrate to one’s very soul and there is the tragedy of all Ireland in his voice.’ [Cont.]

De Valera was entered on the register of births in New York as George, christened as Edward; used Eamon; Kate de Valera [née Coll] remained in USA till her death in 1932; married Charles Wheelwright, and Englishman and a Protestant, in Rochester; two children, a dg. who died, and a son who became a Redemptorist priest; ed. details include Bruree, CBS Rathluirc, and Royal University BA; post-grad. work UCD and TCD; Scottish Borderers involved in Arran Quay shootings, 2 July 1914; in America de Valera responded to queries with, ‘I am an Irish citizen […] I ceased to be an American citizen when I became a soldier of the Irish Republic’; Constitution of 1937 endorsed by plebiscite of 1 July 1937; on the death of an Irish ambassador in Berlin during the War, Ireland could only be represented by a chargé d’affaires due to complications in the royal of the king in the external relations Act.

Bibliography: Lord Longford and Thomas O’Neill, Eamon de Valera (London 1970); Mary C. Bromage, de Valera and the March of a Nation (London 1956); Denis Gwynn, de Valera (NY 1933); David T. Dwane, The Early Life of Eamon de Valera (Dublin 1922); M. J. MacManus, Eamon de Valera (Dublin 1947); Sean O’Faoláin, de Valera (London 1939); also Louis N. Le Roux, Patrick H. Pearse (Dublin n.d.); Hedley McCoy, Patrick Pearse (Cork 1966); Seán Ó Luing, Art Ó Griofa (Dublin 1953); Padraic Colum, Arthur Griffith (1959); Sir James Ferguson, The Curragh Incident (London 1964); A. P. Ryan, Mutiny at the Curragh (London 1956); P S O’Hegarty, The Victory of Sinn Féin (Dublin 1924); C. Desmond Greaves, The Life and Times of James Connolly (London 1961); R. B. McDowell, The Irish Convention 1917-18 (London [line lost]); Documents relative to the Sinn Féin Movement (Cmd. 1108 of 1921); Patrick McCortan [sic], With de Valera in America (NY 1957); Wheeler-Bennett, John Anderson, Viscount Waverley (London 1962); Longford, Peace by Ordeal (Lon; rev. 1962); Bennett-Wheeler, King George VI, his Life and Reign (London 1953).

Additional: Lord Longford & Thomas O’Neill, de Valera (1970): ‘His [de Valera’s] view would be that the Northern Unionists were, at bottom, proud of being Irish; that the history, tradition and culture of the historic Irish nation could not fail to attract them; that the language was a mine of this tradition and culture’ (p.297; quoted in Basil Chubb, The Irish Constitution, 1991, p.30.)

[ top ]

|

Sean O’Casey: ‘He [de Valera] was outside everything except himself. There seemed to be no sound of Irish wind, water, folk chant or birdsong in the dry, dull voice [...] de Valera’s voice was neither cold nor hot - it was simply lukewarm and very dreary.’ (Quoted in J. Ardle McArdle, review of Diarmaid Ferriter, Judging Dev: A Reassessment [...], RIA 2008, in Books Ireland, Oct. 2008, p.226.) |

Denis Johnston, ‘I have always found “Dev” extremely easy to talk to because you never have to act in front of him.’ (See ‘Did you know Yeats? And did you lunch with Shaw?’, in A Paler Shade of Green, ed. Des Hickey & Gus Smith, London: Leslie Frewin 1972, pp.60-72; p.68.)

Richard Kain, Dublin in the Age of William Butler Yeats and James Joyce (Oklahoma UP 1962; Newton Abbot: David Charles 1972): ‘A remarkable feature of modern Irish history is the growing stature of Eamon de Valera during the 1930’s and 1940’s. Few national leaders have survived so much hatred and ridicule. His lean figure and unsmiling face made him a target for cartoonists. His policies have been met with [147] derision. When he attacked the Treaty he was accused of word-splitting, and in the Civil War that followed he seemed guilty of fomenting anarchy. These were the wilderness years. Once hunted by the British, he was now pursued and imprisoned by the Irish of both North Ireland and the Free State. In fact he was a virtual outlaw, rejected by the IRA. and Sinn Fein alike. At this time, as Seán O’Faoláin once observed, he, with his unkempt look, long overcoat, crushed felt hat, and worn brief case, might have been mistaken for any of the thousands of disheveled idealists and misfits who drifted throughout mid-European capitals. But his five and one-half years of political exile, fourteen months of them in prison, were finally ended. In August, 1927, he led his newly formed Fianna Fail party back into the Dail, at the cost of signing the hated oath of allegiance to the English crown. When he explained that he considered a compulsory oath not binding, he was mocked as an opportunist. On his assumption of leadership in 1932, many feared the possibility of a native fascism, and expected that he would retaliate upon his former enemies. His maintenance of neutrality during World War II, popular though it was in Ireland, was cynically attacked in England and America.’ [Cont.]

Richard Kain, Op. Cit. (1972) - cont.: ‘None of the labels has stuck, and few of the fears have materialized. With a dignity that confutes his mockers, de Valera has emerged as a Lincoln who survived the dramatic years of crisis and who has undertaken the drab duties of national recovery. As an obscure mathematics teacher he surprised everyone by becoming one of the most capable commanders in the 1916 Rising. The only leader to survive, he has remained in office ever since, with the exception of his abstention of 1922-27 and the two interludes [148] of 1948-51 and 1954-57. But for millions the world over, de Valera, whether in or out of office, represents the Republic of Ireland. […] As head of the Council of the League of Nations in 1932, de Valera confounded experienced diplomats with his clear demands for disarmament. His opinion of Field Marshal Wilson’s assassination in 1922 had been direct and honest: ”I do not approve, but I must not pretend to misunderstand.” It took courage, or obstinacy if you will, to maintain neutrality in World War II, for it meant closing Irish ports to Americans as well as to British. Yet when Winston Churchill, in his victory broadcast, indulged in self-congratulations on his ”restraint and poise” in not forcing Ireland to concur, and referred to the shamefulness of Irish policy, de Valera made a dignified answer. Knowing, he said, the kind of reply that was expected, indeed the kind of reply that he himself might have made years before, “I shall strive not to be guilty of adding any fuel to the flames of hatred and passion, which, if continued to be fed, promise to burn up whatever is left by the war of decent human feelings in Europe.” In the searing light of Churchill’s rhetoric, these words seem colorless, but they are words of wisdom. Ireland’s tempestuous struggles have ceased, and the dramatic gesture is no longer in fashion, but in the annals of history this clerical idealist will take his place beside his more vivid predecessors. Unlike them, he has not given his countrymen the customary memorable phrases and grand deeds. In fact it might be said that he has brought them little but that rarest of all features of Irish political life-success.’ [150] (pp.147-50; for longer extract [exclusive of this], see under RICORSO Library, “Critics”, attached.)

[ top ]

Robert Kee, The Green Flag (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1972): ‘In a letter to a friend in February 1918, Eamon de Valera wrote that for seven centuries England had held Ireland “as Germany holds Belgium today, by the right of the sword.” This is the classical language of Irish separatism and can be very misleading. [...] Though the sword indeed played its dreadful part there as savagely as in any other country of Europe, to see Irish history in the plain, uncompromisingly nationalistic terms of Mr de Valera’s statement is to miss, together with the truth, much of the poignancy and drama of the strange relationship that persisted between the two islands for so long. It is also the surest way to become bewildered and confused by the very events in which Mr de Valera was then embroiled, as certain obvious facts about these events make plain enough.’

David Thompson, England in the Twentieth Century [2nd ed., rev. by Geoffrey Warner], Pelican History of England 1914-1979 (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1981), Chamberlain accepted de Valera’s Constitution declaring Eire to be a ‘sovereign independent democratic state’ and surrendered ports, April 1938; accepted £10 million in payment of outstanding annuities; de Valera wrote to him, ‘You did more than any former British statesman to make a true friendship between the peoples of our two countries possible’; Warner calls this a testimony from an unexpected source [178], and earlier refers to de Valera’s ‘austere and aloof personally’ which aroused little warmth in the US [71].

John Bowman, de Valera and the Ulster Question, 1917-1973 (Oxford: Clarendon 1982): ‘De Valera believed that the Ulsterman was an Irishman and that partition was a British creation. He also believed that the territorial unity of Ireland took precedence over the wishes and beliefs of the Northern Unionist. De Valera quoted approvingly Mussolini’s speech, ‘There is something about the boundaries that seem to be drawn by the hand of the Almighty which is very different from the boundaries that are drawn by ink upon a map. Frontiers traced by inks on other inks can be modified. It is quite another think when the frontiers were traced by Providence.’ p.302; J. H. Whyte , Interpreting Northern Ireland, OUP 1991, p.131.) Note further, Bowman writes that de Valera ‘sometimes […] went so far as to say that he would abandon the goal of a united Ireland if that necessitated abandoning the language’ (de Valera and the Ulster Question,1982; quoted in Basil Chubb, ‘de Valera and the Constitution’, [chap.] The Irish Constitution, 1991, p.29.)

| John Bowman, ‘When Lloyd George met de Valera: “Why do you insist upon Republic? Saorstat is good enough”’, in The Irish Times (10 July 2021). |

|

| See full-text copy - online or copy - as attached. |

[ top ]

D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland (London: Routledge 1982; new edn. 1991), comments upon the historiography of A. M. Sullivan in The Story of Ireland (1867) and its share in ‘the kind of literature that his, and succeeding generation of Irish nationalists were reared on [of which] Eamon de Valera was perhaps its most celebrated exponent.’ (p.249; see further under Sullivan, supra]; Further, ‘But he had learned much after the harrowing and frustrating years of 1922 to 1926; and now he was prepared to break with Sinn Féin, stop wasting time, and take up the suggestion of one of his ablest lieutenants, Sean Lemass, to found a new party, Fianna Fáil. Lemass’s advice soon proved sound and realistic. In the 1927 general election de Valera’s new party won 44 seats, while Sinn Féin was reduced to five; and the resolutions passed at a Sinn Féin ‘republican government’ meeting in April 1928 must have removed any lingering doubts. In one fell swoop the ‘government’ condemned those deputies who had reneged on the republic in 1922 and 1927, repudiated all acts of the government of Northern Ireland, denied the right of the ‘king of England’ to confer the title ‘earl of Ulster’ on his son, called on the ‘race’ to renew its allegiance to the Government of the republic, and ended with a rhetorical flourish, congratulating the ‘peoples of Egypt, Arabia and India on their determination to assert their absolute independence of the arch-enemy of human liberty’. It was magnificent, but it was also rigidly orthodox, and it was, as de Valera had earlier acknowledged, not politics. (Ibid., p.344.)

Colm Toibín, Walking along the Border (London: Macdonald 1987), writes: ‘There was no sense of habitation anywhere, the population of Leitrim having decreased from 150,000 to 27,000 between 1841 and 1986 because of emigration, famine, and now forestry. I understood why the forests had become an emotional issue. I though of de Valera’s famous St. Patrick’s Day speech broadcast in 1943, when he wished for ‘a land whose countryside would be bright with cosy homesteads, whose fields and villages would be joyous with the soul of industry, with the rompings of sturdy children, the contests of athletic youths and the laughter of comely maidens, whose firesides would be forums for the wisdom of serene old age. It would, in a word, be the home of a people living the life that God desires that man should live.’ / Toibín remarks: ‘Forty later the road between Rossinver and Kiltyclogher, the heart of rural Ireland, was a convincing testament to the failure of de Valera’s vision, which seemed now like a joke from a bitter satirical sketch. He wasn’t a drinking man, but it is likely that even he would have taken a dim view of the plight of the publicans of Kiltyclogher, right there on the border with Fermanagh […]. I drank to de Valera’s poor old ghost.’ (p.67).

Basil Chubb discusses de Valera’s authorship of the 1937 Irish Constitution in The Politics of the Irish Constitution (1991), viz., ’During the Treaty debates and after, Dáil deputies and later IRA members had more interest in the status of the new Ireland [in relation to what de Valera called ‘the big question’ of the Crown] than its size [15]; ”republic” debate, de Valera read out the dictionary definition in answer to a question posed by Deputy Dillon, but said that he had deliberately avoided declaring Ireland a republic in his constitution because he was trying to ‘keep open a bridge over which the Northern Unionists might one day walk.’ He said that this avoidance of the nomenclature ‘puts the question of our international relations in their proper place and that is outside the Constitution’ [24]; de Valera’s] strategy for handing the Northern problem was to relegate it to ‘the back burner’ while he grappled with what he called ‘the big question’ [79]. Further, Chubb notes that Pope Puis XII congratulated de Valera on the fact that the human rights formulations in Bunreacht na hEireann were ‘grounded on the bedrock of the natural law.’ (Ireland: The Weekly Bulletin of the Dept. of External Affairs, No. 421, 13 Oct. 1958; Chubb, op. cit.,p.71]

Joseph Lee, ‘The Irish Constitution of 1937’, in Ireland’s Histories, Aspects of State, Society, and Ideology, ed. Seán Hutton & Paul Stewart (London: Routledge 1991), p.80ff.: Eamon de Valera, under whose close supervision the Constitution was drafted, was a strong believer in the rule of law, and in protecting the rights of the citizens against the intrusive and arbitrary potential of state power. Indeed, had he sought an autocratic state, the Constitution of 1922, which his new Constitution superseded, allowed him immense scope for arbitrary behaviour. [80] de Valera accepted an essentially liberal concept of individual rights […] He was, in this respect, if not a disciple, of Daniel O’Connell. [81] de Valera’s own preferred social order blended Aquinas with Jefferson, his ideal being a democracy of small property owners, with the family as the basic unit of a Christian society which, governed by the precepts of natural law, derived its legitimacy from allegiance to ‘the Most Holy Trinity […] &c., as the preamble portentiously puts it. [81]. Lee goes on to question the meaning of the phrase ”the Irish nation” [88] but generally endorses the constitution as an expression of the political consensus of Irish people, and defends in particular Arts. 2 & 3. [89]

[Cf. Irish Constitution/Bunreacht na hEireann (1937): ‘The State recognises the Family as the natural primary and fundamental unit group of Society (...)’]

T. Ryle Dwyer, de Valera: The Man and The Myths (Swords: Poolbeg 1991), quotes de Valera on his paternity, ‘My father and mother were married in a Catholic church on Sept 9th 1881. I was born in October 1882’; christened George Edward in New York; his Spanish father died and his mother remarried, having sent him home to the half-acre farm in Bruree, Co. Limerick, where he was raised surrounded by lurid speculation about his legitimacy; registered at school under the name of his uncle Pat, as Edward Coll. Quotes, ‘any government that desires to hold power in Ireland should put publicity before all’. ‘[T]hose Unionists who were not willing to accept the 1937 Constitution should be transferred to Britain and replaced by Roman Catholics of Irish extraction from Britain.’ Also, notes that the execution of two men executed in 1940 marked an irrevocable break with the IRA; de Valera came to power with the defeat of W. T. Cosgrave in 1932, and resigned in favour of Seán Lemass in 1959. [cited in review of Dwyer, de Valera: The Man and The Myths in Books Ireland,Oct 1992, q.p.].

T. Ryle Dwyer, Eamon de Valera (1980): ‘[…] de Valera thought, Irishmen living in England should replace intransigent Unionists in Ulster’ (p.112; quoted in J. H. Whyte , Interpreting Northern Ireland, OUP 1991, p.131.) Whyte adds that there was no evidence that Irishmen living in Britain wished to return to Ireland, anymore than that Ulster unionists wished to go to Britain.’ (Quoted in Whyte, op. cit., idem.)

[ top ]

Seán O’Faoláin (1) O’Faoláin remarked: ‘He had no real interest in art. I don’t think he could spell the word. I don’t mean to be critical of him. You see he didn’t need to know anything about art. He only went to the Abbey once. He was from a rural generation. He had no time for art because he didn’t need it.’ (Interview with Brian Kennedy, Cork Review, 1991, p.4-6).

Seán O’Faoláin (2): John Montague, reviewing Julia O’Faolain, Trespassers: A Memoir, in The Irish Times (25 May 2013), tells of the return of the O’Faoláins to Ireland in 1933: ‘[...] the atmosphere had darkened; while Seán’s adoring first book on de Valera extols him as “tall as a spear, commanding, enigmatic”, the second deplores his influence, which has led to “the inhuman treatment of unmarried mothers ... the unimaginative control of juvenile houses of detention ... stupid censorship ... the fanatical ways in which such innocent amusements as dancing ... are controlled.” / No wonder the O’Faoláins became partisan, and no wonder Sean’s wife, Eileen, saved the family bacon with her fairy tales, [..] almost as popular as Patricia Lynch [...] charming, but their popularity at a time when adult books were being suppressed was a bit disturbing, as if southern Ireland wished to be lulled to sleep.’ [Presumably quoting De Valera, 1939.]

Tim Pat Coogan, de Valera: Long Fellow, Long Shadow (London: Hutchinson 1993), Chap. 1: ‘The Harsh Reality of the Nursery’, questions facts about de Valera’s biography as given by himself, arriving that the conclusion that he was probably the son of Aitkinson, his mother’s Clare employer before she left Ireland, rather than the Puerto Rican sculptor. He writes that if de Valera knew or suspected ‘that there was a doubt about his parents marriage, the knowledge must have been a burden to him. It must have had a marked effect on his character, if even a portion of what the psychiatrists tell us about the influences of childhood be true. The death of, or abandonment by, his father, rejection by his mother and growing up in poverty a continent away from her were the sort of experiences which either broke or toughened a man. Did they also dehumanise him? Many would say they did.’ De Valera once told the Dáil that as far as he knew he had no Jewish blood; Coogan also raises the questions of his alleged breakdown under fire at Jacob’s Mill; the financing of the Irish Press; and his refusal to listen to warnings about Arts. 2 & 3.

Tim Pat Coogan, review of T. Ryle Dwyer, Big Fellow, Long Fellow: A Joint Biography of Collins and de Valera (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1998), in Irish Times (19 Dec. 1998), [q.p.]; Coogan dwells considerably on the question of de Valera’s illegitimacy, discounting the rumour that his mother Kate was pregnant when she sailed to New York, but noting that he (Coogan) failed to find a record of marriage at St Patrick’s, Greenville, where Longford and O’Neill state his parents were married; comments that de Valera ‘reinvented himself as having two parents, and, particularily from 1916 onwards, soothed the uncertainties within himself by a singleminded drive for power that would brook no rival for power, either when he was splitting the Irish in America, or the nation back in Ireland’; notes absence of footnotes and damage done by compression.

R. F. Foster, Connections in Irish History and English History (London: Allen Lane/Penguin 1993; rep. 1995): the Manchester Guardian was told by de Valera in 1928 that he hoped ”to free Ireland from the domination of the grosser appetites and induce a mood of spiritual exaltation for a return to Spartan standards” (Round Table report)’. (p.94.) Foster goes on to cite Joseph Lee, ‘if Irish values be deemed spiritual, then spiritualism must be redefined as covetousness tempered by sloth.’ (Idem.)

Fintan O’Toole, ‘Broken Dreams’, Irish Times (26 Aug. 1995), [q.p.] writes on ‘the failures of Dev’; quotes Thomas McCarthy [‘My father recited prayers of memory, of monster meetings, blazing tar-barrells outside Free State homes, the Broy Harriers pushing through the crowd, Blueshirts. And, after the war, de Valera’s words making Churchill’s imperial palette blur’], and poem [‘one decade of darkness. / A mindstifling boredom’]; also a story by Tom MacIntyre (‘Aspects of the Rising’, 1966), in which a prostitute launches stream of invective at Aras an Uachtarain [‘you craw-thumpin’ get of a Spaniard’]; and lines by Paul Durcan [‘I see him in the heat-haze of the day / Blindly stalking us down; / And, levelling his ancient rifle,’ he says, ”Stop Making Love outside Aras an Uachtarain”’; also mentions Rocky de Valera, Ferdia MacAnna’s band in the 1970s , as index of the reduction of de Valera to joke-status.

J. F. Kennedy, Prelude to Leadership: The European Diary of John F. Kennedy (Washington 1995), contains nine typed pages on Ireland incl. remarks on De Valera: ‘I left England yesterday to come to Ireland. World attention has been turned again to Mr de Valera due to his recent remark in the ”Irish Dáil” that Ireland was a Republic.’ Stayed with Ambassador David Gray, and recorded his opinion: ‘Mr Gray’s opinion of de Valera is that he was sincere, incorruptible, also a paranoiac and a lunatic. His premise is that the partition of Ireland is indefensible, and once this thesis is accepted, all else in his policy is consistent. He believed that Germany was going to win. He kept strict neutrality even towards the simplest United States demands.’ Further, ‘He has fought politically in the Dáil the same battle he fought militarily in the field - a battle to end partition, a battle against Britain.’ Doubted agricultural self-sufficiency: ‘not a profitable product for misty, rainy Ireland’. Rebukes Churchill: ‘Churchill’s speech at the end of the war, in which he attacked de Valera, was extraordinarily indiscreet - made things much more difficult for Gray and pulled de Valera out of a hole.’ (See The Irish Times, 20 July 2002, p.8.) See further on Gray, in Notes, infra.

John McDonagh, ‘“Blitzophrenia”: Brendan Kennelly’s Post-Colonial Vision’, in Irish University Review (Autumn/Winter 2003): ‘One of the most enduring “external plastic pictures” of Ireland was portrayed by Eamon de Valera after the end of the Second World War, when in response to Winston Churchill’s thinly veiled criticism of the Free State’s official neutrality, he declared that despite being “clubbed into insensitivity” over “several hundred years” Ireland “stood alone against aggression” and emerged as “a small nation that could never be got to accept defeat and has never surrendered her Soul”. (Quoted in Theodore Hoppen, Ireland Since 1800: Conflict and Conformity, 1989, p.186). This particular interpretation of history is, in K. Theodore Hoppen’s words, “at once the strength and the tragedy of nationalist Ireland’s imprisonment within a special version of the past” and was a reading that could be found in the writings of both Joyce and Yeats (Ibid., p.185). Furthermore, it validates any action taken by the Free State government to define and preserve models of nationhood through its social, cultural, and political policies. Consequently, draconian censorship laws were introduced in the 1920s to [328] protect the cherished, perceived “soul” of the nation from neo-colonial influences. Gradually, a politically dominated image of the nation emerged that equated conservative political policies with strict Catholf social and cultural mores […].’

[ top ]

Quotations

Physical force: ‘Our movement is constitutional in that sense. Constitutional nationalism does not align itself with the British Constitution; it aligns itself with the will of the Irish people.’ (Irish Independent, 29 Oct. 1917; quoted in C. Smyth, Ireland’s Physical Force Tradition Today Lurgan, 1989, p.8; cited in Anthony Alcock, Understanding Ulster, Lurgan 1994, p.29.)

Civil War (order to disarm): ‘Soldiers of Liberty! Legion of the Rearguard! The Republic can no longer be defended successfully by your arms. Further sacrifices on your part would now be in vain, and the continuance of the struggle in arms unwise in the national interest. Military victory must be allowed to rest for the moment with those who have destroyed the Republic.’ (Quoted in Macardle, The Irish Republic, p.371; cited in Peter Costello, The Heart Grown Brutal, 1977, p.238).

|

Assassination of Sir Henry Wilson, 22 June 1922: ‘Anti-Treaty political leader Eamon de Valera, somewhat evasively, said of the shooting, “Killing any human being is an awful act but the life of a humble worker or peasant is the same as the mighty. I do not know who shot Wilson or why, it looks as if it was British soldiers [the two gunmen were Great War veterans] but life has been made hell for the nationalist minority in Belfast especially for the last six months [...] I do not approve, but I must not pretend that I misunderstand.”’ (John Dorney, ‘The Assassion of Sir Henry Wilson’, at The Irish Story online; accessed 26.062020.] |

Clare election (1923): ‘[T]oday the aims of the Irish Republicans, in Ireland and out of Ireland, could be expressed in Wolfe tone’s words, to assert the independence of our country, to unite the whole people of Ireland, to abolish the memory of past dissensions, and to substitute the common name of Irishmen in place of all sectional denominations. That is what Irish Republicans stand for; that is our goal; and our means are every available means by which determined men can win their freedom. / These aims preclude, very definitely, first of all any possible assent by us to the dismemberment of our country. You cannot have a sovereign Ireland if you have Ireland cut in two. […] There are no two Irelands, there are no Northern or Southern Irelands for us. Every Irishman, be he Sir James Craig or the bravest and most extreme man here in the South - they are for us all comprised in the common name of Irishmen, and we will never own that there are two motherlands for us./The sovereignty of Ireland, then, cannot possibly be given away by Irish Republicans.’ (Quoted in Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, 1991, Vol. 3, p.743ff.)

National Territory: ‘We deny that any part of our people can give away the sovereignty or alienate any part of this nation or territory. If this generation should be base enough to consent to give them away, the right to win them back remains unimpaired for those to whom the future will bring the opportunity.’ (10 Dec. 1925; cited in Conor Cruise O’Brien, Ancestral Voices, Religion and Nationalism in Ireland,Poolbeg 1994, p.129.) Further, ‘The only policy for abolishing partition that I can see is for us, in this part of Ireland to use such freedom as we can secure to get for the people in this part of Ireland such conditions as will make the people in the other part of Ireland wish to belong to this part.’ (1 March 1933; O’Brien, op. cit., 1994, p.130.)

Turned backs (on 2nd Reading of Juries Protection Bill, 1st May 1929): ‘Because they [Cosgrave Govt.] turned their backs on what they stood for a few years ago they will not allow their prejudice to let them know that there are men who did not turn their backs on these principles, and who are struggling, rightly or wrongly, either supported by the majority of the Irish people or not supported, to secure this objective. [the Republic]. (Dáil Debates, XXIX, 1576; quoted in Donal O’Sullivan, The Irish Free State and the Senate (London: Faber & Faber 1940, p.258.)

Irish genius: ‘The Irish genius has always sressed spiritual values [...] That is the characteristic that fits the Irish people in a special manner for the task of helping to save western civilisation’ (Radio broadcast of 1933; quoted in Julia O’Faolain, ‘Your mother doesn’t realise that she couldn’t survive without me’, extract from Trespassers, reflecting on her parents marriage. (Irish Times, Weekend Review, 9 March 2013, p.10.)

Radio Éireann (Inaugural broadcast, Athlone; 6th Feb. 1933): ‘Anglo-Irish literature, though far less characteristic of the nation than that produced in the Irish language includes much that is of lasting worth. Ireland has produced in Dean Swift perhaps the greatest satirist in the English language; in Edmund Burke probably the greatest writer in politics; in William Carleton, a novelist of the first rank; in Oliver Goldsmith a poet of rare merit. Henry Grattan was one of the most eloquent oration of his time - the golden age of oratory in the English language. Theobold Wolfe Tone has left us one of the most delightful autobiographies in literature. Several recent, or still living, Irish novelists and poets have produced work which is likely to stand the test of time.’ (Quoted in Anthony Cronin, Heritage Now: Irish Literature in English, 1982, p.[7].)

Telefís Éireann: in his address on the opening of RTÉ, de Valera said: ‘like atomic energy, it can be used for incalculable good but it can also do irreparable harm.’ (See Martin McLoone, Irish Film, London: British Film Inst. 2000, p.207; quoted in Bryan Gaynor, UU Diss., UUC 2009.)

[ top ]

St Patrick’s Day (Broadcast of 17 March 1943: ‘One hundred years ago the Young Irelanders, by holding up the vision of such an Ireland before the people, inspired our nation and moved it spiritually as it had hardly been moved since the golden age of Irish civilisation. Fifty years of the Gaelic League similarly inspired and moved the people of their day, as did the later leaders of the Volunteers. We of this time, if we have the will and the active enthusiasm, have the opportunity to inspire and move our generation in like manner’ [intervening paras. concern Thomas Davis and ’spiritual resources’]; further: ‘… many have got more than is required and are free, if they choose, to devote themselves more completely to cultivating the things of the mind, and in particular those which mark us out as a distinct nation. / The first of these is the national language. It is for us what no other language can be. It is our very own. It is more than a symbol; it is an essential part of our nationhood. It has been moulded by the thought of a hundred generations of our forebears. In it is stored the accumulated experience of a people, our people, who even before Christianity was brought to them were already cultured and living in a well-ordered society. The Irish language spoken in Ireland today is the direct descendant without break of the language our ancestors spoke in those far-off days. / As a vehicle of three thousand years of our history, the language for us is precious beyond measure. As the bearer to us of a philosophy, an outlook on life deeply Christian and rich in practical wisdom, the language today is worth far too much to dream of letting it go. To part with it would be to abandon a great part of ourselves.’ in Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, 1991, Vol. 3, p.749f.) [Cont.]

St Patrick’s Day (Broadcast of 17 March 1943) - cont.: ‘[…] With the language gone we could never aspire again to being more than half a nation. / For my part, I believe that this outstanding mark of our nationhood can be preserved and made forever safe by this generation…it cannot be saved without understanding and co-operation and sacrifice. They are not slight. The task of restoring the language as the everyday speech of our people is a task as great as any nation ever undertook […] The State and public institutions can do much to assist […] The individual citizen must desire actively to restore the language and be prepared to take the pains to learn it and to use it, else real progress cannot be made. […] Let us devote this year to the restoration of the language. […] Time is running against us in this matter of the language. We cannot afford to postpone our effort. We should remember also that the more we preserve and develop our individuality and our characteristics as a distinct nation, the more secure will be our freedom and the more valuable our contribution to humanity when this war is over.’ [Conclusion in Irish: ‘Bail ó Dhia oraibh again bail go gcuire Sé ar an obair atá romhainn / God bless you and bless the work ahead of you.’] (in Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, 1991, Vol. 3, p.749f.) [Cf. Patrick Pearse, on the Irish Language as national ‘essence’ and ‘repository’]

St Patrick’s Day (Broadcast of 17 March 1943) - cont.: ‘The Ireland [which] we dreamed of would be the home of a people who valued material wealth only as a basis of right living, of a people who were satisfied with frugal comfort and devoted their leisure to the things of the spirit; a land whose countryside would be bright with cosy homesteads, whose fields and villages would be joyous with sounds of industry, the romping sturdy children, the contests of athletic youths, the laughter of comely maidens; whose firesides would be the forums of the wisdom of serene old age. [It would, in a word, be the home of a people living the life that God desires men should live.’] (Quoted in Terence Brown, Ireland, A Social and Cultural History, 1981, p.146; also in D. J. Doherty & J. E. Hickey, A Chronology of Irish History Since 1500 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1989), p.125; also C. L. Dallat, ‘The rise of the novel as a critique of de Valera’s Ireland’, in Times Literary Supplement, 27 Sept. 1996, p.21.

St Patrick’s Day (Broadcast of 17 March 1943) - cont.: ‘Since the coming of St. Patrick, fifteen hundred years ago, Ireland has been a Christian and a Catholic nation. All the ruthless attempts made down through the centuries to force her from this allegiance have not shaken her faith. She remains a Catholic nation.’ (Quoted in J. H. Whyte, State and Church, 2nd edn. 1980, p.48; cited in Basil Chubb, The Politics of the Irish Constitution, 1991, p.27.) For commentary see also David Cairns & Shaun Richards, Writing Ireland, colonialism, nationalism and culture, Manchester 1988, p.133).

Dev’s nationality: ‘Go and read the Cork Examiner. The proprietor and editor sent me a letter apologising privately and saying that a certain thing was let through without his knowledge, showing what is happening at some of those meetings where this question of Communism is being discussed. There is not, as far as I know, a single drop of Jewish blood in my veins. I am not one of those who try to attack the Jews or want to make any use of the popular dislike of them. I know that originally they were God’s people; that they turned against Him and that the punishment which their turning against God brought upon them made even Christ Himself weep. In disclaiming that there is no Jewish blood in me I do not want it to be interpreted as an attack upon the Jews. But as there has been, and even from that bench over there, this dirty innuendo and suggestion carded, as I have said, formally to God’s Altar, I say that on both sides of me I come from Catholic stock. My father and mother were married in a Catholic Church, on September 19th, 1881. I was born in October, 1882. I was baptised in a Catholic Church. I was brought up here in a Catholic home. I have lived amongst the Irish people and loved them and loved every blade of grass that grew in this land. I do not care who says, or who tries to pretend that I am not Irish. I say I have been known to be Irish and that I have given everything in me to the Irish nation. (Dáil Debates, 2 March, 1934; quote in Piaras Mac Éinrí, paper on on limits of multiculturalism at ‘Identity and Cultural Diversity in Irish Writing’ Conference, Máirtín Uí Chadhain Th., TCD, 23 Aug. 2003 [hand-out].)

[ top ]

Dev’s Allegiance: ‘I have one allegiance only to the people of Ireland, and that is to do the best we can for the people of Ireland as we conceive it […] I would not like therefore, that anyone should propose me for election as president who would think I had my mind definitely made up on any situation that might arise. I keep myself free to consider each question as it arises - I never bind myself in any other way.’ (Speeches, ed. Moynihan, 1980, p.70.) [See Joseph Lee, Ireland 1912-1985, Politics and Society, Cambridge UP, 1989, p.48].

Statement of principle: ‘[T]he question of going in or remaining out [of Free State Dáil] would be a matter purely of tactics and expediency […] I have always been afraid of our people seeing principles where they really do not exist.’ (Draft letter to Mary MacSwiney; cited in D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland, 1982, p.343.)

National sovereignty (address to the League of Nations): ‘Make no mistake, if on any pretext whatever we were to permit the sovereignty of even the weakest state among us to be unjustly taken away, the whole foundation of the League of Nations would crumble into dust.’ ( Quoted in Conor O’Clery ‘America’ [column], The Irish Times, Sept. 21 2002, p.13.)

Amending the Constitution (Speech of April 1933 at Arbour Hill): ‘Let it be made clar that we yield no willing assent to any form or symbol that is out of keeping with Ireland’sright as a sovereign nation. Let us remove these forms one by one, so that this State that we control may be a Republic in fact and that, when the times comes, the proclaiming of the Republic may involve no more than a ceremony, the form confirmation of a status already attained.’

Draft Articles (corresponding to article 44.1.2. of Bunreacht na hEireann): ‘The State acknowledges that the true religion is that established by our Divine Lord Jesus Christ Himself, which he committed to his Church to protect and propagate, as the guardian and interpreter of true morality. It acknowledges, moreover, that the Church of Christ is the Catholic Church.’ (The Constitution of Ireland, ed. Keogh & Litton, 1988, p.59; quoted in Basil Chubb, The Politics of the Irish Constitution, Dublin: IPA 1991, p.28.)

Irish Language: ‘With the language gone we could never aspire again to being more than half a nation.’ quoted in D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland, London: Routledge 1982, p.22; along with a Republican song: ‘God save the southern part of Ireland / Three quarters of a nation once again.’

Christian Bros.: ‘Ireland owes more than it will probably ever realise to the Christian Brothers. I am an individual who owes practically everything to the Christian Brothers.’ (Quoted in Fintan O’Toole, ‘Blessed Among Brothers’, The Irish Times, Weekend feature, 5 Oct. 1996.)

[ top ]

John Bull: ‘Nothing would please John Bull better than that they should put it into their minds that physical force in any shape or form was morally wrong […]. As to the word “constitutional”, they had no Constitution of Ireland. The English Constitution was not theirs and they were out against it. What he understood as Constitutionalism was that they should act in accordance with the will of the Irish people and the moral law. Their movement was constitutional in that sense.’ (Irish Independent, 29 Oct. 1917; cited in Robert Key, The Green Flag, 1972, p.611.)

Use of arms: ‘There is no way today in which the arms of any section of the people can be used from the point of view of general national defence except under the control of the duly elected government’. (Q. Source; and cf. Michael Collins.)

Garda Siochana: ‘as far as we are able to know […] these officers have loyally served us. We came into office and we got service […] because these men realised that we are not a partisan government.’ (The Way to Peace, Dublin 1934; cited in Boyce, op. cit., 1982, p.345.)

Mayo librarian: the refusal by County Council to appoint Letitia Dunbar-Harrison (BA, TCD) to a librarianship in Co. Mayo in 1930 elicited from De Valera a prevaricating response in the Dail in the course of which he supported the right of the Catholic majority to choose an appointee who shared their culture and religion. The case is dealt with in considerable and somewhat facetious detail, in Joseph Lee, Ireland 1912-1985, Politics and Society (Cambridge UP 1989), pp.161-68; see also Pat Walsh, The Curious Case of the Mayo Librarian (Cork: Mercier Press 2009).

References

Cathach Bks (Catalogue No. 12) lists Peace and War: Speeches on International Affairs [n.d]; Mary C. Dromage, de Valera and the March of a Nation (Lon. 1956); Ireland’s Stand: Being a selection of the speeches of Eamon de Valera during the war 1939-45 (Dublin 1946); David T. Dwane, Early Life of Eamon de Valera (Dublin 1927) [port.]; M. J. MacManus, A Biography [1st ed.] (Dublin 1944). [

Hyland Catalogue, No 220 (Jan. 1996) lists Peace and War: Speeches on International Affairs (1944) [rep.]. Hyland No. 224 notes that there is a portrait of de Valera by Elizabeth Rivers, in London Mercury No. 222.

[ top ]

Notes

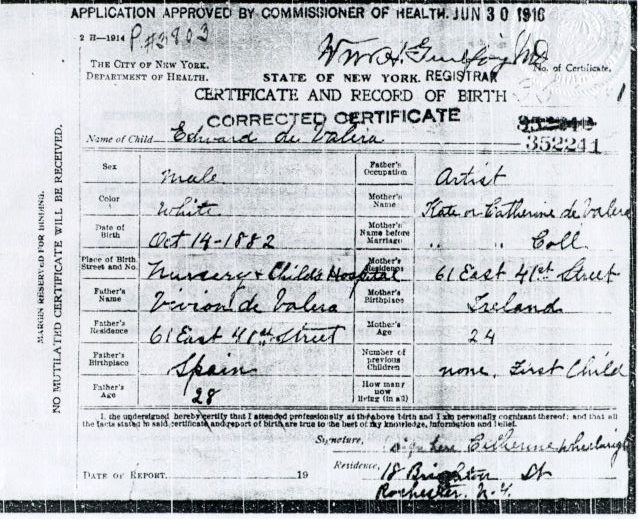

Birth cert. : ‘Eamon de Valera was born in New York City on 14 October 1882. About one month later, Dr. Charles Murray reported the birth to the City’s Health Department. The Doctor recorded de Valera’s first name as George. In 1910, de Valera’s mother Catherine [Coll] applied to the Health Department to amend her son’s birth certificate. She filled-out a new birth certificate indicating her son’s name first name was “Edward”. Her application was approved and a new certificate was pasted over the original certificate. Both are on file in the New York City Municipal Archives.’ (Notable New Yorkers - de Valera page, quoted in Wikipedia, under Eamon de Valera, n.1 [online; accessed 05.11.2009.)

Note: The cancelled certificate gives his father’s name as Vivion de Valero [sic] with profession of ’artist’, while his mother is cited as Kate De Valero - the child’s name being amended to Edward de Valera [sic], the father’s to Vivion de Valera, and the mother’s to Kate (or Catherine) de Valera [née Coll] in the revised cert. (See Notable New Yorkers [online].)

|

[ top ]

W. B. Yeats wrote, ‘Am I a great Lord Chancellor […] Or am I de Valera, / Or the King of Greece, / Or the man that made the motors? / Ach, call me what you please! / Here’s a Monenegrin lute […] [‘The Statesman’s Holiday’, Collected Poems, Macmillan, 1933 / , p.389].

W. B. Yeats voted for de Valera in 1932, and met him to ensure that the Abbey subsidy continued; struck by de Valera’s honesty and simplicity; wrote to Olivia Shakespear that ‘It was a curious experience; each recognised the other’s point of view so completely.’ (27 Feb. [1934]; Wade, ed., Letters, p.820, cited in A. N. Jeffares, W. B. Yeats: A New Biography, 1988, p.314).

Oliver St. John Gogarty: Gogarty described de Valera’s appearance as a ‘cross between a corpse and a cormorant.’ [Q. source.]

Fr. O’Flanagan, brother-in-law of Eamon de Valera, Vice-President of Sinn Féin, attempted negotiation with Lloyd George without consent of the Republican cabinet, and fell out of favour. (See Hilary Pyle, Estella Solomons, Patriot Portraits,1966; incls. a portrait of O’Flanagan.]

Ireland’s reputation: de Valera, as incoming Prime Minister [recte Taoiseach], informed the Dáil in April 1933 that he had told the Abbey directors that certain plays (meaning Synge and O’Casey’s) would damage the good name of Ireland. (See Frank Tuohy, Yeats, 1976, p.194.)

Anthony Cronin begins Heritage Now: Irish Literature in the English Language (Dingle: Brandon 1982) with an essay to which is prefixed a paragraph-length epigraph from a speech of Eamon de Valera according a grudging place to ‘Anglo-Irish Literature’ in 1933.

Republican rear: In ordering the IRA to lay down arms in 1923, de Valera addressed his command to the ‘Rearguard of the Republic’; see also Francis Carty, Legion of the Rearguard (London 1934) [accounts of Collins, Brugha, de Valera, &c.].

Jonathan Bardon, History of Ulster (1992), ‘recounts Sir James Craig’s journey to Dublin to meet de Valera, together with his recollection: ’after half an hour, de Valera ‘had reached the era of Brian Boru. After another half hour he had advanced to the period of some king a century or two later. By this time I was getting tired. … fortunately, a fine Kerry Blue entered the room ..’ [Bardon, 480]. Further, de Valera reported on his side, ‘I must say I liked him’ (Bowman, de Valera and the Ulster Question 1917-1973,Oxford, 1982, p.47; cited in Bardon, op. cit., [q.p.].)

Michael D. Higgins [Senator, Dáil Eireann], The Betrayal, poems (1990), title poem, ded. ‘for my father’, contains lines on de Valera, ‘It was 1964, just after optical benefit / Was rejected by de Valera for the poorer classes / In his Republic, who could not afford, / As he did / to travel to Zurich / For their regular test and their / Rimless glasses.’ Further: ‘you […] debated / Whether de Valera was lucky or brilliant / In getting the British to remember / That he was an American.’ [See also remarks under “Reprieved”, infra.]

[ top ]

Nelson Pillar, O’Connell St., Dublin, blown up by the IRA, reputedly elicited from de Valera the remark that ‘Nelson left Dublin by air.’ (Cited in Thomas Flanagan, ‘Dublin, Ghost and Voices’, in The Sophisticated Traveler (n.d.’; ?Autumn 1995), pp.16-34.

Abbey launch: The Abbey Theatre, designed by Michael Scott, was officially opened in Dublin by Eamon de Valera on 18 July 1966. (See “Highlights of Recent Years”, in The Irish Times, 13 Jan. 2004.)

Special Position: Article 44 of the Irish Constitution [Bunreacht na hEireann], authored by de Valera himself, ‘recognises the special position of the Holy Catholic Apostolic and Roman Church as the guardian of the Faith professed by the great majority of the Citizens’.

Reprieved (1): De Valera’s mother Kate Coll worked as a domestic servant in the Atkinson castle in Co. Clare up to the time of her sudden departure for New York. Her son (born soon afterwards) was sent back to Bruree at a young age. The expenses of his education at Blackrock College were covered by the Atkinsons, who also paid his election costs in 1918. There is a family tradition that John Atkinson, the former Lord Chancellor (to 1905) secured de Valera’s reprieve by personal intercession with the powers that be in 1916. The family was especially offended when ‘Brits Out’ was recently painted on their gateposts. (BS posting to Irish Studies List, Virginia Tech., Monday, 10 Feb 1997.)

Reprieved (2): Lucille Redmond, reviewing Ruán O’Donnelly, ed., The Impact of the 1916 Rising among the Nations, writes: ‘Bernadette Whelan examines how the administration of Woodrow Wilson (himself from a Northern Protestant background) behaved, and finally kills off the legend that de Valera was saved because he was American. It turns out that he was saved because no one really knew who he was.’ (See in Books Ireland, March 2009, p.55.) [See also under Michael D. Higgins, supra.]

[ top ]

Letters sold: A collection of 17 letters from de Valera to his wife between 1911 and 1920, sold by auction at Sale at Tara Towers Hotel; the letters incl. some written while at Mountjoy, with news of the commutation of his sentence. Others date from his time at Tawin Gaelic College, of the Galway shore; ‘I need a kiss urgently … I want to press my wife to my heart, but we are 150 miles apart. Darling, do you think of me at all? - can you sleep without those long limbs wrapped around you? - those same limbs are longing to be wrapped around you again - two weeks - fourteen days - how can I endure it? You do not know how sorrowful I am ..’. The letters includes account of E. R. Dix and Roger Casement visiting Tawin College to judge a cooking prize established by them’ the former ‘wiring into [i.e., eating] a bit of everything’ in the way of food. 6 children with Sinéad. (Report in The Irish Times, 25 Nov. 2000.)

Stolen Letters: Irish Emigrant (Galway) reports that 18 letters written by Eamon de Valera to his young wife Sinéad between 1911 and 1920 and held by a family in England were due to be auctioned in Dublin early in December 2000 when the gardai seized them as having been stolen from the de Valera’s at Cross Ave. (Blackrock) in a burglary about 25 years ago. The unnamed vendors appear to be an innocent party in the matter. (http://www.emigrant.ie; 18th Dec. 2000.)

Dev in America: At the convention for the election of the Republican presidential candidate, De Valera led a torchlit procession of Irish separatists and overshadowed the quieter diplomacy of Judge Cohalan, causing Bishop Gallagher to pass this judgement: ‘if President de Valera had remained away from Chicago and allowed Americans to run their own affairs, the Independence plank would have been in the platforms of both parties, and fear of American public opinion would have stayed the murderous hand of England.’ (Quoted in J. Ardle McArdle, review of Michael Doorley, Irish-American Diaspora Nationalism: The Friends of Irish Freedom 1916-1935, in Books Ireland, Feb. 2006, p.19.)

David Gray, the US minister in Dublin from 1940, was 75 at the time of appointment; husband of Maud, an aunt of Eleanor Roosevelt; sought to prevent long-term Irish reunification; ineptly disrupted theretofore successful relations between Joseph Walshe, the permanent secretary of the Irish Dept. of Foreign Affairs, and the OSS in Ireland; Gray was guided by communications with the Roosevelts and with Alfred Lord Balfour supposedly received through a psychic medium (a lady from Cork); not recalled by FDR to avoid upsetting Eleanor. (See Barry McLoughlin, review of Aengus Nolan, Joseph Walshe: Irish Foreign Policy 1922-1946, Mercier 2007; in Books Ireland, Summer 2008.)

John Hearne (1893-1969): Hearne is the recipient of an inscription made by de Valera on a copy of the Constitution now in the National Library of Ireland, as follows: ‘To Mr John Hearne, Barrister at Law, Legal Adviser to the Department of External Affairs’, Architect in Chief and Draftsman of this Constitution, as a Souvenir of the successful issue of his work and in testimony to the fundamental part he took in framing this first Free Constitution of the Irish People.’ See Brian Kennedy, ‘The Special Position of John Hearne’, in The Irish Times, 8 April 1987; cutting slipped into a copy of Tomás Ó Neill & Pádraig Ó Fiannachta, De Valera (Dublin: Cló Morainn 1968), acquired by BS at Blackrock Market, May 2009. The author asserts and partly demonstrates that Hearne, who attended the Imperial Conference as technical adviser to the delegation led by Kevin O’Higgins, and was, like de Valera, a devout Catholic, with an additional interest in Catholic theology, was indeed the author - subject to the constraint that de Valera wished the Constitution should uphold the rights of the individual and that it should be a popular document that the man in the street could read - here quoting Maurice Moynihan [q. source]. Also cites, inter. al., C. S. Todd and Dermot Keogh; see further under Anthony Cronin, supra.]

Lloyd George: The British PM complained that talking with de Valera was like ‘trying to pick up mercury with a fork’, to which de Valera responded, ‘why didn’t he use a spoon?’ (Cited in Tony Canavan, review of Conor O’Clery, Ireland in Quotations: A History of the Twentieth Century, 1999; in Books Ireland, Dec. 1999, p.358.)

John Dillon: Dillon, in opposition, reputedly declared of de Valera: ‘when my people went into Irish politics, his were still selling budgerigars in Barcelona.’

[ top ]

Herr Hempel: Diarmaid Ferriter notes that de Valera’s condolences to Herr Hempel and - more generally - the Irish lack of contemporary response to the seriousness of the Jewish Holocaust perpetrated by the Nazis was conditioned by the neutrality policy of the day and especially by the news blackout dictated by the government, quoting Clair Wills: ‘the crucial factor which lamed the humanitarian response was the inability to contemplate, let alone comprehend, the true meaning and scale of the Jewish persecution until it was too late [...] a reporting of the war denuded of all commentary, stripped of all specific reference to atrocity, produced its own kind of falsehood.’ (See ‘Complexity of era defined Irish neutrality in war’, in The Irish Times, 4 Feb. 2012, “Opinion” column; a response to Minister Alan Shatter’s speech accusing Ireland of a tarnished legacy that ‘delimits Ireland’s moral authority’ to be critical of the Israel today (i.e., in ts treatment of Palestinians).

Response: see letter by Prof. Geoffrey Roberts (History School, Univ. Coll., Cork [UCC]): argues that Irish neutrality cannot be construed as purely pragmatic, citing a speech of Robert Brennan, Irish ambassador to the USA, in 1942, in which he compared neutral Ireland to the medieval Ireland of saints and scholars who kept the light of civilisation burning during the dark ages, and speculated that after the Second World War, Ireland might be called once again to a mission of enlightenment. Roberts remarks that ‘Brennan’s comments reveal that the Irish political elite - and a good part of the population, too - considered neutrality to be morally superior to the position of all participants in the war, including the anti-fascist Allied coalition. Such was the hubris that led Éamon de Valera to deliver his condolences on the death of Hitler.’ Further argues that Ireland would have entered the war with America if the position had been pragmatic and identifies of the historian’s responsibility ‘to represent past reality in its full complexity.’ (Irish Times, Lettters, 8 Feb. 1012, p.17.)

See also Paul Bew, ‘What did Churchill really think about Ireland?’, in The Irish Times (8 Feb. 2012), citing his willingness to speak before nationalists at the Ulster Hall on 8th Feb. 1912 - apparently spurred by his exasperation at the Unionists’ rejection of reasonable offers, while holding that his support for the Home Rule Bill of 1912 was always qualified by a view that substantial partitionist concession should be made to Ulster unionism. Quotes Churchill’ speech: ‘History and poetry, justive and good sense, alike demand that this race, gifted, virtuous and brave, which has lived so long and endured so much should not, in view of her passionate desire, be shut out of the family of nations and should not be lost forever among indiscriminate multitudes of men’. Paul holds that Churchill viewed a new relationship between Great Britain and Ireland as fostering ‘the federation of English speaking peoples all over the world’ - and that he his hopes were blighted by the electoral rise of de Valera and the dominance of Anglophobic separatism in Irish politics. In April 1940, Churchill told the incoming American ambassador David Gray (Roosevelt’s cousin) that he would not be party to any overriding of the Ulster Unionists’ wishes in an attempt to get Ireland onside in the crisis; as late as 1948, Harold Nicolson and Sir John Maffey (UK Ambassador to Ireland) told Sean MacBride in the Kildare St. Club that Churchill‘ ’s apparent sympathy with Irish unity was based on his expectation of closer links with Britain. (p.16; includes part of undate photo of Churchill and de Valera.)

Terence de Valera (usu. “Terry”), a younger son and the father of Síle de Valera, published a memoir in 2004.

Portraits: Among many others, chiefly photo-ports., there is a portrait by Seán O’Sullivan, 1931 [NGI]; the standard biography, arl of Longford and Thomas P. O’Neill, Eamon de Valera (1970), has been superseded by the more critical account in T. P. Coogan, The Long Fellow (1993).

Namesake: A Full View of Popery, in a satyrical account of the lives of the popes, &c. To this is added, a Confutation of the Mass. By a learned Spanish convert [C. de Valera], now trans [by J. Savage] (1704). The same is author of works on Hertfordshire and Somerset and Romance and classical translations.

[ top ]