Life

| [Anthony Gerard Richard Cronin; fam. Tony] b. Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, 28 Dec 1923; son of a reporter on the Enniscorthy Echo and small-shop keeper, managed by his mother Hannah (née Barrron); ed. Blackrock College, were he wrote his first poems, and UCD; afterwards at King’s Inns (BL); ass. ed., and later ed., The Bell, 1952-55, before moving to to London; participated in the 1954 Bloomsday tour with John Ryan, Patrick Kavanagh, Brian O’Nolan [Flann O’Brien], and Thomas Joyce; active member of S.E. Dublin Branch of Labour Party; wrote introduction to a selection of new poems by Patrick Kavanagh which appeared in Nimbus, ed. David Wright (London; April 1956) - emphasising the ‘poetic repose and contemplation which is at the heart of the satire’ [presum. The Great Hunger]; served as lit. editor Time and Tide, 1956-58; issued “RMS Titanic” (1960), arising from his fascination with the film, Night to Remember; rep. in the Penguin anthology of Longer Contemporary Poems (ed., Wright); issued Life of Riley (1964), an autobiographical novel in which sundry contemporary persons appear including Louis McNiece, Cecil Salkeld and Francis Stuart as well as, most prominently, Peadar O’Donnell [as Prunshios [var. Proinnsías] McGonaghy who is ‘wurred [i.e., wired] into the diolectic’], acted as lit. ed. of The Bell [here The Trumpet]; m. Thérèse Campbell, with whom he had two daughters, Iseult (d.1976, and Sarah); |

| issued A Question of Modernity (1966), essays, the chief of which deals with Joyce in a post-colonial vein that anticipates Declan Kiberd and others; appt. visiting lecturer, Univ. of Montana, 1966-68; wrote a play, The Shame of It (Peacock 1974); appt. Poet in Residence, Drake Univ., 1968-70; issued Collected Poems 1950-73 (1973); issued Dead as Doornails (1976), a prose narrative of the Irish literary ’fifties and centrally about Kavanagh, Behan and Flann O’Brien; issued Reductionist Poem (1980); appt. Cultural and Artistic Adviser to the Taoiseach [Charles Haughey], 1980-83, and again in 1987-92; served as Irish Times columnist (“Viewpoint”, 1974-80 - later issued as An Irish Eye (1985); issued Identity Papers (1980), a novel about Richard Pigott’s grand-son - the forger in the Parnell Commission case - as he supposes; issued 41 Sonnet Poems (1982) and New and Selected Poems (1982); appt. founding Chairman of Aosdana, 1983, and a member of its governing body, the Toscaireacht, until his death; |

| issued Heritage Now: Irish Literature in the English Language (1982), essays; organised a state reception at Dublin Castle for the Joyce Centenary, attended by Juan Luis Borges, Francis Stuart, and others; received the Marten Toonder Award for contrib. to Irish Literature, 1983; contrib. to innumerable journals[orig. Irish Times column essays]; separated from his wife Thérèse (d. 1998) 1985, and afterwards married Anne Haverty [q.v.]; issued The End of the Modern World (1989), a sonnet sequence - though the preface denies that they are a suite; produced television programmes incl. “Between Two Canals” and “Flann O’Brien - Man of Parts”; contributed ‘Anthony Cronin’s Private Anthology’ to Sunday Independent; issued The Last Modernist (1996), a ‘slightly authorised’ biography of Samuel Beckett, launched in Shelbourne Hotel, 15th Oct. 1997; m. Anne Haverty, 2003 and settled at 30 Oakley Rd., in Ranelagh, Dublin; faced criticism for supposed plagiarism from recently published life of Beckett by James Knowlson, detected by Bruce Arnold from examination of the publisher’s proof; issued Collected Poems (2004); |

| awarded DLitt. by UCD, 2006; travelled to New Delhi with Derek Mahon and Anne Haverty to read poetry for the Irish Literature Exchange, Jan. 2008; elected Saoi of Aosdána; issued The Fall (2010), a new collection; his RMS Titanic was set to music and song by Donal Lunny, with Allison Sleator and Feargal Murray accompanying Cronin (as reader), being premiered at Kilkenny Arts Festival, 2012 where he appeared in conversation with Colm Tóibín at the Ormonde Hotel [Kilkenny], 12 Aug. 2012; later toured in Ireland - Pavilion Th., Dun Laoghaire, 3 Oct. 2013; Tinahely, Co. Wicklow; Belfast, &c., April 2014; issued Body and Soul (2014), a poetry collection; d. 27 Dec. 2016; funeral service held at Church of the Sacred Heart, Donnybrook, 31 Dec. 2016 - attended by President Michael D. Higgins who called him the ‘complete, consummate man’; credited by Colm Tóibín with giving ‘dignity and stability to the creative life’ in Ireland through his role in the formation of Aosdána; cremated in a wicker coffin at the Victorian Church in Harold’s Cross, there is a pencil portrait by Brian Maguire; the Guardian obituary is by Tóibín. DIW DIL OCIL FDA |

| Bio-dates: Irish Times obituary notice gives his age at death as 88; The Guardian gives his dates as 28 Dec. 1923-27 Dec. 2016; the birth-date 1926 is given in The Oxford Companion to Irish Literature (ed. Robert Welch, 1996), while the year 1928 is given in Cronin’s response to the Writer’s Questionnaire compiled at the Coleraine Centre for Irish Literature & Bibliography in 1997. Further details in this last source: |

|

| Also cites published works and journalism incl. Viewpoint (weekly, later fortnightly column on art, literature, politics, philosophy for Irish Times 1974-1986. |

|

| Anthony Cronin (photograph by Brenda Fitzsimons) |

| See the 1954 Bloomsday video - infra. |

|

|

[ top ]

Works| Poetry collections |

|

See trans., La fin du monde moderne [extraits], trad. de l’anglais, trad. collective, Royaumont, relue et complétée par Pascale Guibert [Les cahiers de Royaumont; n.s., 3] (Paris: Créaphis 1994), 45pp. [22cm.] |

| Fiction (novels) |

|

| Drama |

|

| [ top ] |

| Biography |

|

| Criticism & Commentary |

|

|

| [ top ] |

| Miscellaneous |

|

| Art & Artists |

|

|

| [ top ] |

| Discography |

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Collected Poems (Dublin: New Island [2004), 333pp. ded. ‘For Anne, Without Whom ...’ CONTENTS: Epitaph [1]; For a Father [2]; Liking Corners [3]; Writing [4]; Prophet [5]; Apology [6]; Lines for a Painter [7]; Presuming to Advise [9]; The Futility of Trying to Explain [10]; Odd Number [11]; Humiliation [12]; The Lover [13]; Encounter [14]; Elegy for the Nightbound [15]; Baudelaire in Brussels [17]; Inheritors [18]; Consolation [19]; Balance Sheet [20]; Dualities of Destiny [2[1]; Surprise [2[2 Examination of Conscience [23]; Fairways’ Faraway [24]; Outside [25]; Others than Us [26]; Small Hours [27]; Reflections on Fear and Courage [28]; Experience [29]; Anarchist [30]; Realities [31]; Distances [32]; The Risk [33]; Moscow in Winter [34]; R.M.S. Titanic [35]; Responsibilities [51]; The Persuaders [53]; Dualities of Pride [55]; Elysium [57]; Narcissus [58]; On a Change in Literary Fashion [59]; Character [61]; Blessed Are the Poor in Spirit [66]; War Poem [68]; The Elephant to the Girl in Bertram Mills’ Circus [71]; Obligations [73]; Enquirers [74]; Summer Poem: Ireland [75]; At the Zoo [77]; To Certain Authors [79]; To Silence the Envy in My Thought [80]; Lunchtime Table, Davy Byrne’s [82]; Letter to an Englishman [84]; Return Thoughts [96]; On Compiling Entries for an Encyclopedia [98]; Familiar [99]; Another Version [100]; The Man Who Went Absent from the Native Literature [102]; Homage to the Rural Writers, Past and Present, at Home and Abroad [106]; For the Damned Part [108]; A Form of Elegy for the Poet Brian Higgins (1930-1965) [109]; Reductionist Poem [111]; Not Easy [131]; The General [133]; The Decadents of the 1890s [134]; Soho, Forty Eighth Street and Points West [136]; The Middle Years [138]; Mortal Conflicts [139]; No Longer True about Tyrants [141]; La Difference [143]; Sine Qua Non [145]; Returned Yank [146]; Completion [147]; Concord [148]; Last Rites [149]; In Praise of Constriction [151]; The End of the Modern World [159]; Strange [259]; Agnostic’s Prayer [260]; Reminder [262]; 1989 [263]; Athene’s Shield [265]; Poem Which Accompanied the Planting of a Tree of Liberty on Vinegar Hill, 14 July 1989 [267]; Admirable [268]; Shadows [269]; Sorry [270]; Encounter [271]; Relationships [272]; Funeral [274]; The Intelligent Mr O’Hare [275]; In Praise of Hestia, Goddess of the Hearth Fire [277]; Aubade [279]; No Promise [280]; On Seeing Lord Tennyson’s Nightcap at Westport House [281]; Without Us [282]; Thoughts about Women’s Beauty [283]; How They Are Attracted [284]; Ovid [285]; Living on an Island [286]; An Interruption [287]; The Need of Words [289]; Happiness [290]; Sex-war Veteran [29[1]; Pity the Poor Mothers of This Sad World [293]; The Manifestation [296]; 1798 [297]; The Lovers [298]; The Minotaur [301]; Why? [317]; Boys Playing Football [318]; And That Day in El Divino Salvador [320]; The Incarnation [321]; Our Pup Butler [323]; Guardians [324]; William, Conor’s “The Riveters” [325]; The Trouble with Alpho Queally [326]; Art [328]; Meditation on a Clare Cliff-top [330].

Heritage Now: Irish Literature in English (Dingle: Brandon 1982), 255pp. CONTENTS: ‘Maria Edgeworth: The Unlikely Precursor’, pp.17-30; ‘Thomas Moore: The Necessary Bard’, pp.37-46; ‘James Clarence Mangan: The Necessary Maudit’, pp.47-50 ‘William Allingham: The Lure of London’, pp.61-68 ‘George Moore: The Self-Made Modern’, pp.69-74; ‘Somerville & Ross: Women Fighting Back’, pp.75-86; ‘John Millington Synge: Apart from Anthropology’, pp.95-104 ‘The Advent of Bloom’, pp.105-42, also ‘Footnote for a Poet’, pp.143-46; ‘James Stephens: The Gift of the Gab’, pp.147-55; ‘Thomas MacGreevy: Modernism Not Triumphant,’ pp.155-60; ‘Francis Stuart: Religion without Revelation’, pp.161-67; ‘Samuel Beckett: Murphy Becomes Unnamable’, pp.169-85 ‘Patrick Kavanagh: Alive and Well in Dublin’, pp.185-96; ‘Louis MacNeice: London and Lost Irishness’, pp.197-202; ‘Flann O’Brien: The Flawed Achievement’, pp.203-14. [Note that critical comments in these essays are copied to RICORSO pages on sundry writers.]

Heritage Now (1982): “Bibliographical Note” cites Speeches of Eamon de Valera, ed Moynihan; Thomas MacDonagh, Literature in Ireland [Kenniket Edn.]; P. H. Newby, Maria Edgeworth; T. de Vere White, Thomas Moore; Patrick Buckland, Irish Unionism: the Anglo-Irish and the New Ireland 1885-1922; C. C. O’Brien, Writers and Politics; Daniel Corkery, Synge and Anglo-Irish Literature; Robin Skelton, J.M Synge and his World; Frank Budgen, James Joyce ad the Making of Ulysses; Stanislaus Joyce, My Brother’s Keeper; Stanislaus Joyce, The Complete Diary, ed. George M. Healey; W. Y. Tindall, James Joyce: His Way of Interpreting the Contemporary World; J. Mitchell Morse, The Sympathetic Alien: Joyce and Catholicism; A. Walton Litz, The Art of James Joyce; Augustine Martin, James Stephens: A Critical Study; Anthony Cronin, Dead as Doornails.] (See also under “Quotations”, infra.)

X: A Quaterly Review - Issue No. 1

ed. Patrick Swift

- E-bay Auction; starting bid £12.50

no bids; ended 26 April 2013. ]

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

[ top ]

Commentary

Brian Kennedy, ‘The Special Position of John Hearne’, in The Irish Times (8 April 1987) - comments on Cronin’s characterisation of Eamon de Valera as putative author of the 1937 Constitution: ‘Anthony Cronin, in an article titled “Matters Constitutional” (Irish Times, 18 Nov. 1986), has presented de Valera as a pseudo-chef masquerading as a lawyer, spicing up his constitution with “a dash of Maritain”, “a glimpse of corporatism”, and “a good strong dash of the Papal Encyclical Quadragesimo Anno.” Mr. Cronin has overstated his case, although he does so in a most entertaining fashion. He finds the Constitution to be a “Catholic document” full of “hedging statements” and noteworthy for “Dev’s ghostly presence”. / “Besides being a metaphysician with a reactionary cast of mind, Dev was also a hob lawyer whose ability to split hairs and evidence [sic for evident] delight in doing so was far, far greater than that of his Belevedere and Bar Library opponents.” / While debating with de Valera has been compared to trying to pick up mercury with a fork, he was not a lawyer, not even a hob lawyer. The responsibility for the legal framework of the Constitution lay with John Hearne and he was not a hob lawyer either. He was an internationally regarded legal expert. / As for the “dash of Maritain”, the “glimpse of corporatism”, the Papal Encyclical of 1931, Hearne may well have contributed to their influence. Both he and de Valera were daily communcants, but unlike de Valera, he had a personal interest in in philosophy and theology which had been nurtured during his years at Maynooth. [...; &c.; see further under de Valera, infra.]

Seamus Heaney, The Government of the Tongue (London: Faber 1988), ‘[…] I am aware of a certain partisan strain in the criticism of Irish poetry, deriving from remarks by Samuel Beckett in the 1930s and developed most notably by Anthony Cronin. This criticism regards the vogue for poetry based on images from a country background as a derogation of literary responsibility and some sort of negative Irish feedback. It was deliberately polemical and might be worth taking up in another context’. (p.8.)

James Cahalan, The Irish Novel (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1988), p.300f.: quotes Cronin’s remarks on Flann O’Brien: ‘He deconstructed his own text long before deconstruction was ever heard of ... Here we have an author who pre-empts the methodology of contempurary criticism and confuses its established categories, misplacing himself in date to such an extent as to cast doubt on whether such a phenomenon as post-modernism can be said to exist, and deconstructing his own text before anybody else can get their hands on it. What, in such a case, is criticism to do?’ Cahalan summarises Life of Riley in these terms: ‘Patrick Riley’s downward progression from itinerant jobs in Dublin to total lethargy in England; serving as assistant editor to the Trumpet, ill-advised by Marxist editor Prunshios McGonaghy [Peadar O’Donnell] to visit a dosshouse in England to fully understand “the dioloctic [for dialectic] process”.’ (Riley, p.110; Cahalan, p.300.)

Further: Cahalan quotes Cronin as referring to the ‘curious stancelessness’ of Ulysses and its ‘absence of plot’, with further remarks to the effect that some Irish novelists ‘may have been simply incapable of constructing an ordinary machinery of dramatic causation. It may be that, like Joyce, some of them were uninterested in doing so.’ (Heritage Now, p.25, 26.) Further quotes the comment: ‘Does anyone read Carleton’s novels nowadays, barring Mr Benedict Kiely and a few students and academics?’ (Irish Times, 1974; quoted in James O’Brien [ed.], Carleton Newsletter, 5, 1974).

Further: Cahalan cites Cronin’s view that Somerville & Ross created the ‘stage Anglo-Irishman’ (see chap. on Somerville and Ross in Heritage Now, 1982, p.60), and his calling the “Cruiskeen Lawn” a column that ‘deservedly attained a local celebrity far surpassing that of any individual piece of journalism that twentieth century Ireland has known’ (quoted in de Bréadún, Irish Times, 3 April 1986, p.8).

Gerard Keenan, ‘Anthony Cronin’, The Professional, the Amateur, and the Other Thing: Essays from ‘The Honest Ulsterman’ (Honest Ulsterman Publ. 1995), pp.1-12: ‘... [T]he pages on Behan are among the most sensitive and stirring in modern Irish literature. Indeed, they are a new dimension in Irish literature, as tenderness and compassion are singularly absent from the literature – we are an island of smart-alecs and hard men, the emotionally scarred ... Cronin writes with admirable candour about Behan’s homosexuality (p.8); ‘A Characteristic of Behan, overlooked by Cronin, but which seems plain to the [8] reader, is that one of the most driving motivations in all Behan’s actions was social climbing. Cronin was a barrister. To an amusing degree, he appears to hate all reference to this. Yet it meant an awful lot to Behan’ (p.9). ‘Cronin exhibits much art in writing of Doornails. First he establishes the three main characters, Behan, Kavanagh, and Myles; then he begins to reveal the interplay between them, the almost absurd intensity of their relationships. Then he abandons them, shifts the scene to London, relates with equal sensitivity his experiences with the old guard of the 1940s bohemia of Fitzrovia, of the Fitzroy Tavern and the Wheatsheaf in north Soho. By the time he returns to Dublin the characters there have been broken, they are close to death, their talent already dead [9] and recognised by themselves to be dead. Proust must be evoked. ... Dead as Doornails is not a collection of anecdote. Scenes ... always [serve] to develop one’s understanding of [Kavanagh, O’Brien, Behan] (p.10).

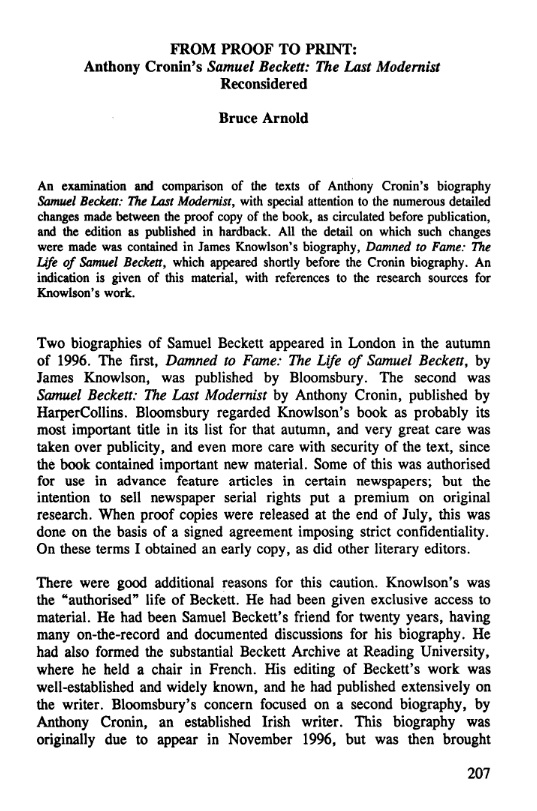

Bruce Arnold, ‘From Proof to Print: Anthony Cronin’s Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist Reconsidered’, in Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui, Vol. 8 [Poetry and Prose / Poésies et autres proses] ([Leiden: Brill] 1999), pp. 207-19 - Summary: ‘An examination and comparison of the texts of Anthony Cronin’s biography Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist, wth special attention to the numerous detailed changes made between the proof copy of the book, circulated before its publication, and the edition as published in hardback. All the details on which such changes were made was contained in James Knowlson’s biography, Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett, which appeared shortly before the Cronin biography. An indication is given of this material, with references to the research sources for Knowlson’s book’.

|

TEXT [Bruce Arnold, ‘From Proof to Print: Anthony Cronin’s Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist Reconsidered’] - cont.: ‘Two biographies of Samuel Beckett appeared in London in the autumn of 1996. The first, Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett, by James Knowlson, was published by Bloomsbury. The second was Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist by Anthony Cronin, published by HarperCollins. Bloomsbury regarded Knowlson’s book as probably its most important title in its list for that autumn, and very great care was taken over publicity, and even more care with the security of the text, since the book contained important new material. Some of this was authorised for use in advance feature articles in certain newspapers; but the intention to sell newspaper serial rights put a premium on original research. When proof copies were released at the end of July, this was done on the basis of a signed agreement imposing strict confidentiality. On these terms I obtained an early copy, as did other literary editors. / There were good reasons for this caution. Knowlson’s was the “authorised” life of Beckett. He had been given access to material. He had been Samuel Beckett’s friend for twenty years, having many on-the-record and documented discussions for his biography. He has also formed the substantial Beckett Archive at Reading University, where he held a chair in French. His editing of Beckett’s work was well-established and widely known, and he had published extensively on the writer. Bloomsbury’s concern was focused on a second biography, by Anthony Cronin, an established Irish writer. This biography was originally due to appear in November 1996, but was then brought [207] forward [...]’. (Available at JSTOR - online; first page accessed 29.12.2016; noticed by David Wheatley on Facebook, 28.12.2016.)

Rita Kelly, ‘The Sinew of Memory’, review of The Minotaur and Other Poems, in Books Ireland (March 2000), p.65: ‘There is no question about it, Anthony Cronin is both a major writer and a major thinker in our times in this country. [...] His poetry is one aspect of expression, there are many, and they all overlap into one large intelligent nebula. Always at ease with the longer poem, unlike Carson, his tone is steady, structured and constant. There is no mad and breathless spill of things. // He may reach moments of great humour when he takes on that ebullience and boyish spills and thrills, there is a serious underlying truth of course, but Cronin holds the position of observer and commentator not voyeur. He takes no prisoners as in “Boys playing football”: ‘Three little boys are playing / with a football / Outside my window [...] / They have now been joined / By what seems to be a fond parent. / Head empty as the ball, / Like all inadequate personalities / He delights in being the instructor. / A very modern Sweet Auburn, a very different Goldsmith.’

Brian Fallon, Anthony Cronin: Man of Letters (Cranagh Press [Univ. of Ulster 2003): ‘[...] Cronin’s era shone at a kind of high-grade literary journalism and polemical writing which today seems almost extinct. This was particularly suited to the style and spaces of the literary magazine and, in fact, did a good deal to dictate its format [...] Cronin’s often excellent literary criticism goes back to his days on The Bell and to his years in literary London - including anonymous long reviews for the Times Literary Supplement, and no doubt much besides. His “Viewpoint” column in The Irish Times contained many excellent, encapsulated critical essays, but when he came to publish a selection in book form, he chose to concentrate on the pieces of political and social comment. Heritage Now, one of his vintage publications, contains excellent thinkpieces on Joyce, George Moore, Somerville and Ross, even a reconsideration of Thomas Moore which is a model of level-headedness. But a genre which he has virtually made his own is the literary portrait - especially those of Brendan Behan, Kavanagh and Brian O’Nolan in Dead as Doornails. One of the reasons why I found his biography of O’Nolan anticlimactic was that he had set down the core of it, and more memorably too, in the preceeding work - in fact, the original pen-portrait really left nothing further to say either on the man or on his work. One the other hand his biography of Beckett is a classic of its kind, which gives the lie to hostile critics who hold [11] that he is excellent in the short critical article or the personal snapshot, but lacks the scholarly stamina to tackle a work of sustained, accurate research. Beckett is an author with whom he can identify fully, and in fact Waiting for Godot is quintessentially as much a testament of the Nineteen-fifties as Maeterlinck’s Pelléas and Melisande is of the Nineties. / Dead as Doornails remains my favourite of all Cronin’s prose books and is now a recognised classic, though The Life of Riley is a comic novel with verve and a genuine satiric sting (it is no secret that the magazine editor portrayed, or caricatured, is based on Peadar O’Donnell, editor of The Bell after O’Faolain). Yet Cronin, after all, might claim that he is primarily a poet, though my own feeling is that he is essentially an all-rounder - neither a poet who writes prose, like the late Robert Graves, nor a prose-writer who publishes occasional books of verse. Both activities seem equally essential to him, and he does not rob one to pay the other. His place in Irish postwar poetry has never been quite staked out by critics and anthologists, and as has been mentioned already, he emerged at a time when Auden was the dominant influence on the younger Irish poets. Some of these early poems, particularly the sonnet “Baudelaire in Brussels”, quickly became anthology pieces and should still rank as such; but much of the later verse has had no more than a coterie readership and his poetic development has been rather overshadowed in the eyes of the public and the critics by Thomas Kinsella, generally regarded as the laureate of that particular generation. / I do not doubt, personally, that his departure to London at a crucial period of his life and career partially shut him out of the eyes and memories of literary Dublin. [...; 13]The Carcanet Press Collected Poems of 1982 was rather a mixed bag, which was also hampered by an unattractive format; nevertheless it has been badly neglected by critics, and even by fellow-poets. (For example, Thomas Kinsella, normally a sensible and open-minded critic, excluded Cronin entirely from his Oxford Book of Modern Irish Verse in 1986.) In particular, his long poem “R.M.S. Titanic” shows a real ability to experiment expressively with free verse and to develop a theme contrapuntally over a long distance [...] the early verse, by contrast, had mostly been written in rather tight, almost neo-classical formats, which at least rules our discursiveness but also makes for short-windedness. Taken as a whole, Cronin’s verse is in a wide range of tone and modes, though often deliberately angular and unmelodic: sometimes ultra-personal and autobiographical, at other times consciously detached and ironic, at other times again narrative and objective, or with an epigrammatic dryness which looks back to the 18th century.’ (pp.11-13.) Fallon reminds us that in London ‘both Cronin and Patrick Swift moved in a milieu which included Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, Robert Colquhoun among the painters, and George Barker, David Wright and many others.’ (p.12.)

Fintan O’Toole, ‘Unfairly neglected? Not now’, in The Irish Times (Thurs, 26 Nov. 2004): ‘[...] With the publication of Cronin’s Collected Poems, bringing together a body of work written over the past half-century, it does not seem at all absurd to suggest that his poetry has not received the attention it deserves. Cronin’s long poems in particular - RMS Titanic, first published in 1961, Letter To An Englishman, written in 1975, and the sonnet sequence The End Of The Modern World, published in 1989 - stand out as a distinctive achievement. Their lucid arguments, muscular but accessible language, technical skill and wry engagement with the contemporary world may stand at an angle to the typical Irish lyric of recent times, but they occupy their own space with an impressive confidence. / If this body of work has tended to drop off the radar of critics and literary historians, however, it is partly because Cronin himself has generated so much interference. His public profile as a combative literary journalist who also wrote about horse racing, as the biographer of Samuel Beckett and Flann O’Brien and as the cultural politician who helped to create, through his relationship with Haughey, Aosdána, the Heritage Council and the Irish Museum of Modern Art has been at odds with the common view of the contemplative poet. [...]’ (See also Quotations, infra.)

Fred Johnston, ‘No Intellectual Tradition’, review of Collected Poems [omnibus review], in Books Ireland, March 2005): Johnston suggests that Cronin’s engagement with ‘Great Themes’ and ‘well-intentioned intellectualism’ are in contrast with his ease in a ‘literary world not much larger, if somewhat cosier, than the [one] which he documented so well in Dead as Doornails.’ His account of the poems weighs the ironies of Cronin’s position in regard to his ideas also: ‘His thinking is astute, sharp, concise and worth interrogating even if to question it. It strives towards a world-view, at least a European view, and speaks out of an English sceptical literary tradition.’ (pp.52-53.)

Further (Fred Johnston, ‘No Intellectual Tradition’, in Books Ireland, March 2005) - quotes “The Man Who Went Absent from his Native Literature”: ‘Nevertheless: / He did not bang a local drum. / He did not give a hoot who won the tribal conflicts’ - and comments: ‘This is not merely anti-Yeatsian, it’s anti-Kavanagh, with his heroic local [?warriors]. The poem rather brusquely rejects most things traditionally considered as accessories in any modern poet’s work-bag; it expresses the paradoxical - and perhaps impossible to filful yet arguably central wish of any thinking rejectionist: to be forward-looking without being utterly Utopian or silly. [...] but the poem is caught up in its own posed dilemma. Rejection of myth is, by most new thinkers, considered to be not really very positive in the long-run. [...]’ Johnston ends by quoting the conclusion from the ‘poignant poem’ “Why?” (‘Why am I always apart and thinking? / Why is my heart so often sinking?’): ‘O let me be one of them sometime soon’.

George Szirtes, ‘Passionate in public’, review of Anthony Cronin, Collected Poems, in The Irish Times (18 Dec. 2004), Weekend: ‘[...] Anthony Cronin is of the first kind, a thinking man who happens to be a poet and a remarkably fine one at that. The late C.H. Sisson is quoted on the back flap of these Collected Poems to the effect that it is the best of Irish prose that has entered Cronin’s poetry. He is right. Cronin’s gift is for the memorable articulation of experience that might have been rendered less memorably in prose. This makes for a passionate and public kind of poetry. Cronin’s engagement is with the ordinary intelligent man in the city street, not with gods, ghosts, the muse, the unknown or the Other. He is aware of these entities, and in his longest and most important poem, the cycle of sonnets titled “The End of the Modern World” he does fleetingly address the muse in the guise of Diana, the moon goddess, but she is not his main concern. Far from it! In the same poem, which is in effect a spectacular lecture on the history of capitalism, the character Childe Roland appears as a modern man in the world of the market’s Dark Tower. [...] The Dark Tower, it should be added, is in Manhattan, and has been the dark tower to others since Cronin’s poem was first published in the key year of 1989, the year when Reagan’s “evil empire” fell apart, leaving the tower in sole charge. In this respect, The End of the Modern World is a tortured meditation on the loss of an ideal that was never fully embodied, and anticipates an argument with Fukuyama’s The End of History.’ Further: ‘Argument is at the core of Cronin’s poetry. [...] Cronin has written beautiful love poems, and some imperious political verse. It was his bad luck that his poem on the Titanic was overshadowed by Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s greater work. But Cronin’s is a major voice: he is Ireland’s modern Dryden, a master of the public word in the public place.’ (See full text and quotation, as infra.)

Paddy Woodworth, ‘Vita brevis, ars longa’, “Charles J. Haughey” [special supplement], in The Irish Times (14 June 2006): ‘A controversy about the genesis of Aosdána, however, ultimately revealed that events of a GUBU nature occurred even in this relatively benigh area of Mr Haughey’s activities. In 1991, a history of the relationship between the State and the arts in Ireland, Dreams and Responsibilities, was published by the Arts Council. The author, Dr Brian Kennedy, inclined to the view that the credit for initiating Aosdána belonged with a former director of the Arts Council, Mr Colm Ó Briain, rather than with Mr Cronin. / After initially publicising the book with great enthusiasm, the council’s then director, Mr Adrian Munnelly, told his officers that he had given Mr Cronin an assurance that he would no longer actively promote it. Mr Cronin has always denied seeking or getting such an assurance, but Mr Munnelly subsequently had the book displayed for sale with Mr Cronin’s version of events attached to it by a rubber band, a device which was christened “the intellectual condom”. / Mr Munnelly shredded some 200 copies of the book, without informing the author. This was an unprecedented action by a director whose personal integrity was highly respected. Mr Munnelly reaffirmed his belief in the book’s value and accuracy when challenged to account for his action by the resignation of one of his officers, Ms Emer McNamara, but it wasn’t republished under his directorship. That the book also recorded the less-than-happy relationship between Mr, Haughey and the council in the early 1980s inevitably created speculation that the Taoiseach himself would not have been displeased to see the book drop from view. / Knowing what we know about his highhanded actions in other areas has made it harder to give him the benefit of the doubt, and assume that he really was as distant from this unsavoury little episode as he claimed in the Dáil. [...].’

| Michael O’Loughlin, in Poetry Ireland Review, 102 (Dec. 2010), pp.26-37: |

|

[ top ]

Colm Tóibín, ‘Anthony Cronin’ [obituary], in The Guardian (24 Jan. 2017) ‘[...] Cronin was, for more than half a century, Ireland’s most prominent man of letters. Although he was called to the bar, he never practised. A true bohemian, he moved easily and effortlessly between Dublin and London and Spain. In the 1950s, he was editor of the influential journal the Bell in Dublin and was later the literary editor of Time and Tide in London. He wrote regularly for the Times Literary Supplement and was one of the first to recognise the importance of Samuel Beckett as a writer of prose. / As an Irish poet, Cronin was unusual in not writing about landscape or childhood or large questions of Irish identity. His poems were often formal in their structure and wry in their tone. He liked clear statement and paradox. He was concerned with fragility and human frailty, but also with public events. He wrote a long poem, RMS Titanic (1961); his interest in modernity and history culminated in an extended sonnet sequence The End of the Modern World (1989). / When the chance came to become involved in government, Cronin, as a socialist working for a conservative prime minister, understood the dangers, but saw that they were outshone by what could be gained. He served as cultural and artistic adviser from 1980 to 1983, and again in Haughey’s third term in office, from 1987 to 1992. [...;]’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library > Criticism > Reviews - via Index or as attached.)

Bruce Stewart, ‘In Memoriam Anthony Cronin (1928-2016)’, in Parish Review: Journal of Flann O’Brien Studies, (Spring 2018), pp.102-07. The passing of Anthony Cronin on 27 December 2016, just one day short of his 88th birthday, brings an end to our living connection with the literary scene in Dublin of the 1950s, a scene dominated by the larger-than-life figures of Patrick Kavanagh, Brian O’Nolan, and Brendan Behan. Tony was a poet, a novelist, a critic, and a cultural activist. He was a lovely man, kind, pensive and amusing yet our loss seems less because he succeeded so well in recording all he knew and understood about those others both as writers and as mortals in Dead as Doornails (1976) and No Laughing Matter (1989) - books which, together with essay-collections such as A Question of Modernity (1960) and Heritage Now (1982) comprise an indispensable guide to modern Irish writing. His longer poem RMS Titanic (1961), which was anthologised for Penguin Poems in 1966 along with others by Auden, W. S. Graham, Hugh MacDiarmid, George Barker and Kavanagh secured him a permanent place in the English tradition of longer verse writing. Among a dozen poetry collections, his sonnet series The End of the Modern World (1989) exhibits a glittering knowledge on the global history of modern times. His Collected Poems, published by New Island Press in 2004, garnered wide plaudits though his reputation for good work never gelled into that of a major Irish poet. His debut novel The Life of Riley (1964) supplies a sardonic account of the exiguous lives of Irish men of letters in the era of The Bell and Envoy journals, as well as glimpses of literary London at the end of the age of ‘little magazines’ - on one of which (Time and Tide) he served as literary editor in the late 1950s. Spells as writer in residence and visiting professor on American campuses in the 1960s reinforced an overseas perspective which accounts in some measure for the cosmopolitan turn of mind so pervasively evident in his way of viewing Irish society and culture, like Seán O’Faolain before him.

Anthony Cronin will be remembered as the owner of an incisive style charged with clarity and a certain wryness which he lustily employed to express an immense capacity for sound literary judgement, but also as a biographer whose manner was informed by a critical intelligence that stripped away the inessentials and set down the reality in terms of social causation and the individual character of the portrait subject. It might be added that he was the product of an educational regime in which the vaunted ‘methodology’ of university research was less rara avis than res ignotum and there is no -ism in his writings. Human memory was still the central resource and, where it failed, the imagination was always ready to supply the deficit. While many Irish academics today actually attain to the standard of literary writing, the biographer who is a writer first and foremost is now a rarity indeed. Anthony Cronin was both the finest and the last example of that breed to have lived in Ireland in our time. In poetry and fiction, criticism, biography and journalism, but also cultural administration, he showed himself to be an eminent member of the profession whose title which Joyce chose to adopt for his own passport, ‘Man of Letters.’ It is no cliché in this case to evoke Tomás Ó Croímtháin’s eulogistic phrase, we shall not see his like again. [End]

See full-text copy in RICORSO Library > Criticism > Reviews - as infra; also available as .pdf at The Parish Review - online; accessed 05.08.2021.

[ top ]

| RMS Titanic |

|

|

|

| —Extract given in The Independent [IE] (01.01.2017) - available online; posted on Facebook by Annie Rose 16.04.2019. |

[ top ]

| “Liking Corners” (1960) |

|

| “Poem of the Week”, in Times Literary Supplement (3 Jan. 2017) - available online; accessed 16.04.2019. |

| “Poem Which Accompanied The Planting of a Tree of Liberty on Vinegar Hill, July 2nd, 1989” | |

|

Saw it enhaloed for a moment, lost it On Vinegar Hill above the pleasant Slaney |

| In Poetry Ireland Iss. 27 [1989]- available online; accessed 05.06.2023. | |

[ top ]

“The End of the Modern World”: ‘[the poet hears above] the murmur of the traffic / A voice ask what it profited to save / One’s solipsistic, self-regarding soul / If one should lose the real world in that saving?’ (Quoted in George Szirtes, ‘Passionate in public’, review of Collected Poems, in The Irish Times, 18 Dec. 2004; as supra.)

“The Manifestation”, a poem printed in Books Ireland (March 1997), ends: ‘[W]hy should the goddess / Ever deign to split / Our imprisoning reality again?’ (Rep. Minotaur 1996.)

Our Gaelic poets: ‘Our Gaelic poets, going about the West, / Blinded with rage and sorrow / Among the sodden green hills, and feeling / The destruction of the wind, / Knowing that poor men’s pride / Was only a drunkard’s boast / And wanting a firelit hall / And a prince’s head to be bowed / In acquiescence to the word [...]’ (Quoted in Fred Johnston, ‘No Intellectual Tradition’, omnibus review in Books Ireland, March 2005, p.53.)

from “Revenant” What is the meaning of this,

That the heart is stabbed with grief,

At the onset of autumn evenings,

At memory’s twitch on the leaf?

The meaning is summer going,

Ridiculous ecstasy, pain,

And the heart agreeing with something

Which was, and which ought to be, plain.—Quoted by Colm Tóibín, obituary, in The Guardian (24 Jan. 2017) - as attached.

[ top ]

‘The Master’s Poetry’ [on James Joyce], in Viewpoint (Irish Times [column], 15 June 1979); discusses the poetry of Joyce: ‘When Stanislaus said that “a poet ... was lost to the world in Dublin in 1902”, he was wrong. Ulysses, more than any other prose work in the English language, has the texture, the intensity, the visual and aural qualities of poetry and could only have been written by a poet. Also writes about ‘The Church Triumphant’ in anticipation of the papal visit (Viewpoint, 24 Aug. 1979), and follows up with ‘What Next?’ (Irish Times, 23 Nov. 1979): ‘[...] those nutty ... enough to hope for a Christian transformation of society were bound to be disappointed’; goes on to argue that Christ was ‘a classical anarchist’, and that a Christian society would be one without pensionable jobs.

The Life of Riley (1964); Patrick Riley is Assistant to the Secretary of to Irish Grocers’ Association; he inhabits “The Warrens” [i.e., the Catacombs of Dublin memory], run by Sir Mortlake; O’Turks [McDaids], The pub population is made up of beggars, steamers, and occasionally an artistic women (foreign) on a Lawrentian mission to the Irish (e.g. Eunice). ‘[...] as has often been remarked, nature has blessed the island of the Gael with a pleniful supply of rainfall and a plentitude of personable females. The shortage lay rather in the circles in which most of those present spent their leisured, in fact their waking hours. ... the Celto-Iberian order of things prevailed, the women closeted in an atmosphere of domestic fecundity ... [O]n this part of the sea-coast of Bohemia, if Bohemia it was, a heterogeneous collection of males had been washed up with an insufficient supply of women. That there was difficulty in recruitment from the outside may be attributed not only to the innate respectability or chastity of the females of the race, but to their fastidiousness as well. [33] Such females as were available to the unattached could no longer gratify the aesthetic sense of possession after difficulty, to say nothing of the Herod complex, with its preference for youth.’ [34] ‘... a girl called Bridget, a student nurse [34], she herself lived in a sort of hostel with fifty or sixty of her fellows, a sort of virginal beehive ... [35]; She had no objection to those occasions to what passions I was shaken or taken by, not to their rudimentary consummation. She was a good girl in that respect. But in spite of my descriptions of the bliss that lay in store for her also, if only she would allow me to finish the matter off properly, she was adamant in her refusal to enter unknown territory where putative social as well as certain moral disaster might lurk.’ [36]; “The Gurriers” become the name of his alternate dwelling; ‘Gurrier is a word I find it rather difficult to define. Not that its not a word of precise application, in the sense that the justness or otherwise of that application is not immediately apparent, but that gurrier elements in a personality can crop up in widely different contexts. Thus, for instance, a Cabinet Minister can be, and frequently is, justly described as a gurrier ... An element of shiftiness is implied, and perhaps an element of braggadacio. A certain lack of respectability is almost certainly imputed, ... An element of shabbiness of style’ [?] Marxist Prunshios McGonaghy and The Trumpet ‘wurred in’; Radio Eireann; Seumas McMurkagaun, the religious novelist, he looked like several common men rolled into one, cattle jobber, schoolmaster, politician, publican, Knight of Columbanus, member of the Gaelic League. Cambden Town dosshouse. ‘Ashtowk, Paddy!’; BBC [personnel], Coosins, the fake Irishman, former Belfast barrister, Boddells, and former business, McLoosh, all at the Stork [pub]; ‘Unemployment had risen sharply during the years of the Labour adminstration. You couldn’t even get a job shouting ‘mind the doors’ on the underground – this I remember particularly because it seemed to me to be a very creative and satisfying job and represented in a quiet secretive dreamy sort of way, an ideal.’ [169]; Interviews with Labour Exchange and National Assistance Board in Southwark. [172] Coosins takes him to a lady with a cotton plantation in Sierra Leone, called Amelia [188]

The Shame of It (1971): Y: ‘I decided to choose a different kind of segregation. To avoid cross-infection. ... I used to go drinking with the boys, the hard men. (Sings, badly.) “And she’ll put it in, and I’ll put it in, and we’ll both put it in together.” One of these days a thought will strike me in the street and I’ll collapse. A prominent citizen collapsed and died of shame while waiting for a number eleven bus last night.’ X: ‘For fuck’s sake be quiet. I can hear them tramplin’ round overhead.’ (Dublin Magazine, Autumn 1921, p.65.)

[ top ]

Heritage Now - Irish Literature in the English Language (Dingle: Brandon 1982) opens with an epigraph framing remarks taken from a speech of Eamon de Valera given at the opening the Radio Eireann in 1933 according a grudging place to the ‘Anglo-Irish writers’ [see De Valera, infra]. Cronin’s “Introduction” sets out from remarks of Samuel Beckett’s “Recent Irish Poetry” reproving the tendency to impose “Irishness” on Irish literature in English and to make it the express subject of that literature. Cronin continues: ‘The present writer does, as it happens, believe that it is important for Irish people anyway to recognise the “Irishness” of their literature. The reflection any country or people obtains from its literature is at least as important a means of strengthening [13] and exploring identity as is anything else. The possession of a literature is as important as is the possession of a language. Again, the establishment of an independent literature is at least as important as the establishment of an independent state; and it could be argued that in many matters the authors have so far shown more signs of independence than the state has.’ He goes on to offer a provisional account if Irish literary qualities: ‘The principal characteristics of the best of our literature in English have been its daring, its humours, its humanity, its true internationalism, its willingness to face ultimates and go to extremes.’ Further: ‘But there are equally those, of whom Synge, and to a degree, Kavanagh, may stand as example, where the Irishness or otherwise has been a source of confusion to criticism and where I have believed it important to put it in its place.’ [14]. In his essay on Beckett, Cronin writes: ‘Murphy ... gives expression to an attitude which is at the core of all Beckett’s work: not of renunciation, for there is nothing but filth to renounce, but rather of desire, of yearning for selfhood, true selfhood at last.’ (p.176.) This collection reprints his essay on Bloom in Ulysses from A Question of Modernity. (Note that Cronin does not treat O’Casey.)

Lord Mountbatten (assassinated): ‘Every time something like this happens, we retreat into the shock of self-abasement and fail to face the difficulties of urging on each other the only way forward that the country can take. [i.e., unity under nationalist banner].’ (An Irish Eye: Viewpoints, 1985; q.p.).

Irish Literary Revival: ‘Once upon a time there was a thing called The Irish Literary Revival, which was connected with another thing called The Celtic Twilight, which was more like a fog. It descended (if that be the word) a long time ago, but it hasn’t cleared away yet and the smell continues to pollute the air [.../]. Now, such as it was, the Irish Literary Revival was an offshoot of British needs. Materialistic, moneyed, torpid late Victorian society wanted an anti-materialist Land of Heart’s Desire whose existence could be checked on the map and whose literary representatives could be produced in drawing rooms once their boots had been cleaned to prove how charming and delightful it all was. Yeats and his friends elected to supply such a never-never land.’ (Irish Times, 3 Nov. 1976; quoted in Alan Warner, A Guide to Anglo-Irish Literature, Dublin, 1981, p.8.)

[ top ]

No Laughing Matter: The Life and Times of Flann O’Brien (1989)|

The hold of Catholicism in Ireland in those years was partly parental. To disavow the faith, whether in public or in private, was a gesture so extreme that most people who had doubts or reservations suppressed them on the grounds that it would cause their parents too much suffering, might indeed even ‘break their hearts’. True, Joyce had managed the business a quarter of a century or so before, but the extreme song and dance he had made of it showed how difficult he found it; and he had, after all, to refuse to kneel at his mother’s bedside, to go into exile and to render himself both déraciné and déclassé to do it. |

| [For longer extracts, see under Flann O’Brien, infra.] |

| The following extract is quoted by John Banville from No Laughing Matter, in his review-article of same, in New York Review of Books (Nov. 1999): |

|

| See John Banville, ‘The Tragicomic Dubliner’, review of No Laughing Matter: The Life and Times of Flann O’Brien by Anthony Cronin, and At Swim-Two-Birds, in The New York Review of Books (18 Nov. 1999) [available online]. Banville comments: "[...] |

|

| See also ‘My Hero: Flann O’Brien by John Banville’, in The Guardian (1 April 2016): |

|

[ top ]

Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist (London: Flamingo 1997): ‘To those associated with an Irish literary monthly, Envoy, of whom the present writer was one, had been shown Watt by Con Leventhal and, immediately struck by the dissolving beauty of its prose, had offered to publish an extract. / Except to people like Leventhal who had been his contemporaries and boon companions in the thirties, and who now seemed to most of [403] us to belong to a different era than ourselves, the name Beckett had only very vague connotations for the post-war generation in Ireland. It was known that he had published a comic novel of some sort in the thirties and that he lived in Paris, but he had very little identity otherwise. However, his composer cousin, John Beckett, belonged to the same group as the editors of the magazine. When he produced a copy of Murphy, I had rather disliked its knowing tone and thought the first sentence falsely sophisticated and untrue. Watt suggested a different order of things. Perhaps Irish modernism had not after all come to an end with James Joyce and Flann O’Brien.’ (pp.403-04). [For the first chapter, see RICORSO Library, “Criticism - Classics > Anglo-Irish Literature”, Cronin, as infra. See further under Beckett, as supra.]

[ top ]

Sundry Remarks

1916 Rising: ‘[...] One supposes that 1916 was in some sense necessary. It was certainly inevitable, given that “once in every generation” &c. and that the British ruling class, having its own form of death wish, had embarked on a suicidal war. The years of nationalist and Catholic triumphalism that followed left us a craven people; but at least we were craven before our own gods.’ (Contribution to Dermot Bolger, ed., Letters from the New Island, 16 on 16: Irish Writers on the Easter Rising (Raven Arts Press 1988), 47pp., pp.16; also cited in Edna Longley, The Living Stream: Literature and Revisionism in Ireland, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: Bloodaxe 1994, pp.84-85).

[ top ]

Typecasting: ‘In Ireland for some reason [...] people want the poet to seem poetic, whereas in other countries poets spend a lot of their time avoiding seeming poetic. And there is a serious disapproval of poets’ complicating matters by doing other things. Right from the beginning, as a young fella writing controversial articles, in the Bell - attacking Sean MacBride’s pretensions, for example - people couldn’t quite believe that someone who was up that sort of thing was a proper poet. Academia is all right, because it’s quiet and separated and never makes waves, but what I was doing typecast me. Involvement with Charlie [Haughey] was only a larger piece of typecasting.’ (Quoted [verbatim] in Fintan O’Toole, ‘Unfairly neglected? Not now’, in The Irish Times, 26 Nov. 2004, p.14.)

Patrick Kavanagh, ‘In the case of the relationship with nature the critic soon enough comes to another easily discernible full stop, for over and over again the poet says about nature and the visible world that to name it and advert to it and declare one’s consciounsess of it with love and passion is enough, and not infrequently declares further ... that this is all you can do.’ (‘Kavanagh Assessed’, in The Irish Times, 1977; q.d.).

‘The Great Humour’ [article on Patrick Kavanagh], Magill (Oct. 1997), incls. the sentence: ‘Few things would have provoked him more than the humourless solemnity with which the new liberal Ireland conducts it self-congratulatory discussions, but it would have provoked him to laughter.’ (p.51; see further under Kavanagh, q.v..)

The First Bloomsday: ‘The first “Bloomsday” celebration, which took place in 1954 was largely Myles na Gopaleen’s idea. It would be wrong to say that in 1954 Joyce was a neglected figure in Ireland. He was, in many quarters, seriously disapproved of, hated might not be too strong a word to describe the attitude. Not only the Church and the devout disapproved of him. Politicians feared to make any reference to a notorious blasphemer and in that very year Sean MacBride, the Minister for External Affairs, had pointedly refused to open a James Joyce exhibition in Paris. Though public rosary recitals had formed part of the attractions on offer in a big tourist drive the previous year, there had been no mention of the sinful Shem the Penman. Even the literary establishment disapproved - most of O’Connor and O’Faolain’s references were in one way or another denigratory, partly, no doubt, because Joyce seemed to have abolished the narrative forms which were their stock-in-trade. And Irish academia was remarkably reticent on the subject of the work that now preoccupies it so greatly.

Further: So our gesture was partly an assertion of his importance to us as well as a rebellion against dullness, hypocrisy and ignorance but it was also a celebration. All those who too part knew the book more or less by heart. Even Kavanagh, who, in accordance with his general policy of running down any Irish writer, young or old, living or dead, who was the object of any praise, here or elsewhere, sometimes expressed reservations, would frequently and for the most part gleefully quote it. And Myles, though fed up with being described by those who knew no better as a “Joycean” writer and therefore occasionally impelled to snarl at the mention of the name, fully understood the greatness of the master and his achievement. And as for my younger self, 1 believed - and, incidentally, still believe - that Joyce was not only the greatest European novelist of the twentieth century, but one of the greatest writers who ever lived, worthy to be mentioned with Shakespeare, Tolstoy and Homer’.

(Source: Blackrock Society Proceedings 2004, pp.66-67, with port. [detail] and photo. of Cronin in white cap launching Blackrock’s Bloomsday Centenary Celebrations. Another photo shows Cronic outside Goggins of Monkstown, with a horse-drawn cab bearing Myles na gCopaleen [Flann O’Brien], with caption ‘[...] Cronin is helping Myles whose hat can be seen emerging from the second cab.)

[ top ]

References

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3: selects Dead as Doornails [523-35]; from New and Selected Poems, ‘Concord’, ‘Plentitude’, ‘Baudelaire in Brussels’, ‘For a Father’, ‘Prophet’; BIOG, 559 [as above], REMS, 1309 [Others like Cronin found in the squalor of bohemian Dublin vague intimations of the dire poverty that surrounded it, and sought uneasily for analogies in Baudelaire and the writers of the French decadence]University of Ulster Library holds [b. 1928]; The Life of Riley (Secker & Warburg 1964 & reps.); Identity Paper (Co-op Books 1980); Poems (Cresset Press 1958); Collected Poems 1950-73 (New Writers 1973); Reductionist Poem (Raven Arts 1980); 41 Sonnets, Poems 1992 (Raven Arts 1992, rep. 1989); New & Selected Poems (Carcanet Press 1992); The End of The Modern World (Raven Arts 1989); A Question of Modernity ([Secker] 1966); Heritage Now (Brandon 1982); An Irish Eye (Brandon 1985); Art for the People (Raven Arts 1988); No Laughing Matter, The Life and Times of Flann O’Brien (Grafton 1989, rep. 1990); also “Viewpoint” [weekly, Later fortnightly column on art, literature, politics, philosophy for Irish Times 1974-1986]; contribution to many other journals, television and radio features.

The Belfast Linen Hall Library holds An Irish Eye: Viewpoints, by A. Cronin [from The Irish Times] (1985).

[ top ]

Notes

The Life of Riley (1964) incls. among its characters to whom Riley turns in his attempts to make a living or regain his poise after another alcoholic collapse: Prionnsías, the lit. ed. of The Trumpet; the Secretary of the Grocer’s Assocation, for whom he acts as secretary to the Secretary; the girlfriend Bridget, how tires of supporting him; Sir George Dermot, owner of Ardash in the Dublin Mountains where he hosts Obe Jasus, a Nigerian intellectual, plays Mahler’s “Song of the Earth” to his guests and is assisted by Uncle Aspey as chef; Sir Mortlake, major domo in the windowless basement on a Georgian square [the Catacombs, on Fitzwilliam Pl., off Merrion Sq.]. The novel includes a sojourn as a literary Irishman in London under the wing of F. R. Higgins. For extended remarks see Catríona MacKernan, in Books Ireland (Dec. 2010), in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index or as attached.

Time and Tide, sometimes called a women’s magazine, published E. M. Delafield’s Diary of A Provincial Lady (1930) in serial form during the 1930s; it was illustrated by Arthur Watts.

Credit due: Cronin writes about Brian O’Nolan’s [aka Flann O’Brien] uncompleted “Slat[t]ery’s Sago Saga”, ‘the basic joke was suggested by the enthusiastic schemes of a character in a novel of my own, The Life of Riley, who envisages the extraction of electricity from potatoes, the paving of the streets of Dublin with sods of turf ... &c.’ (See No Laughing Matter: The Life and Times of Flann O’Brien, London: Grafton 1989, p.264.)

| Cronin’s Birthdate is given as 1926 in Hogan, ed., Dictionary of Irish Literature (1979) and also in Cleeve, Dictionary of Irish Writers (1988), but as 1928 in his own submission to Coleraine Dataset (1996). |

To Russia with ...?: The release of State Paper under the 30 years rule, The Irish Times (1&2/1/1993) prints Dublin Castle contains notes on the journey of Anthony Cronin with James Plunkett and others to Russia by sea; Plunkett is described as ‘very religious’ and Liam Mac Gabhann (called McGowan) as a socialist; the whole group described as liberals or left-wing intellectuals’; Irish Times also prints an extract from Cronin’s article following the visit, entitled ‘Behind the Iron Curtain.’ Further, ‘It seemed to me a terribly depressing country [...] We all, I think, went out of curiosity and we are a curious (in both senses of the word) lot of people. Nobody tried to convert us to communism, and our host did go to great lengths to ensure that we saw what we wanted to see and met the sort of people we wanted to meet’; but ‘at least for one western intellectual there was no place like home.’ The party which travelled by air met with demands of money from the Soviet representatives in London; the sea-travellers paid £21 for their fare.

‘Aosdana: A Comment’, in The Crane Bag [ Minorities in Ireland [with The Church-State Debate; Special Issue], ed. Timothy Kearney, Vol. 5 No. 1 (1981), pp.783-84, contains a commentary on Cronin’s decision to serve Charles Haughey as Cultural and Artistic Adviser:: ‘Mr Cronin’s decision to join the Civil Service so late in life came as a surprise to some. After all, here was a man who, throughout seventies, had emerged in the columns of the Irish times as one of the few critical commentators in the land, a fearless intellectual whose integrity was uncompromised by an academic posting or a party political affiliation. The news of his appointment came a mater of days after he had shared a platform with the revolutionary Pierre Frank and was something of a blow to his many admirers. But then in Ireland the classical way of silencing a rebel has been to give him a seat next to the boss. / Nevertheless, half a loaf is better than no bread, and few would now question the wisdom of Mr Cronin in taking the job. [… &c.]’ (p.782).

Aosdana defended: “John Banville and Aosdana”, a letter by Cronin to The Irish Times, argues that Banville is mistaken about ‘the nature and purposes of Aosdána’ in supposing that it is for the support of ‘what he calls “hungry” people’; further expresses surprise at his ‘crusading zeal’, arguing that the most members of Aosdána ‘enjoy, like him, a degree of financial success understand that membership is also an expression of identity of interest with others who have made the same difficult and often dangerous vocational choice as they have themselves but may not have the same good fortune.’ (20 Dec. 2001.)

Rude awakening: 200 copies of Brian Kennedy, Dreams and Responsibilities, The State and the Arts in Independent Ireland (Arts Council 1992), were sent to the shredder and reissued with an appended pamphlet by Anthony Cronin responding to the account of the foundation of Aosdana therein. (See Irish Literary Supplement, Winter 1993.)

Income stated: In 1992, Anthony Cronin’s income from the Taoiseach’s office became a matter of public record. In answer to a Dáil question it was stated that he received £134 per day five days a week during the Irish EC presidency and the same for four days each week thereafter.

Whiteboys & Defenders: James Smyth, ed. The Men of No Property: Irish Radicals and Popular politics in the late eighteenth century (Gill & Macmillan 1992) 263pp., on Whiteboys and Defenders; ends by quoting Anthony Cronin’s opinion that Defenderism survives as ‘gut atholic nationalism’; a book by revisionist for revisionists.

Hugh Kenner quotes Cronin’s earlier view of the prose descriptions of nature in The Third Policeman as being ‘full of oddly generalised and amorphous description, that of landscape, which occupies such a large part of it, being composed in the most laborious way out of mere landscape-elements, like a child’s picture.’ (Irish Times, 12 Dec. 1975; rep. Imhof, ed., Alive-alive O!, 1985, p.115; cited in Kenner, ‘The Fourth Policeman’, in Anne Clune and Tess Hurson, eds., Conjuring Complexities, 1997, p.64.)

C. H. Peake (James Joyce: The Artist and the Citizen, London: Arnold 1977), quotes Cronin’s observation that Stephen Dedalus ‘specifically rejects in so many words any aesthetic based on symbolism’ (A Question of Modernity, 1966, p.66; Peake, p.9.)

Zinovy Zinik, ‘Dublin dragomans’, in Times Literary Supplement (25 June 2004), a memoir of Anthony Burgess, recalls a meeting with Burgess and ‘Dublin senator and memoirist Anthony Cronin’: ‘Cronin had also gone down the classic route of a Dublin pilgrim in his day: he left with Brendan Behan for Paris - for the legendary Paris of Joce and beckett - only to return a few years later, disillusioned, to his Dublin, and the Dublin legends of the same genii loci. It was Cronin who told Burgess about my presence in Dublin, on that memorable day in June.’ (q.p.)

Colm Toibin cites Cronin’s Collected Poems in ‘Who Read What in 2004’ (Irish Times, Dec. 2004): ‘The tone and range, from the lyrical to the comic, from the complex and hard to the strangely reverential, are genuinely astonishing and make this an essential book for all tose who care about Irish poetry and all those who don ‘t.’

Portraits: Cronin features in the series of photographs relating to the first Bloomsday trip of 1954 [see supra], including one of Cronin at the reins of a horse-drawn carriage [i.e, cab] standing in Duke St., with Davy Byrne’s in the near background, and with Patrick Kavanagh seated beside him, which is printed with a review by Anne Haverty of The Writers and Artists of Dublin’s Baggotonia, by Brendan Lynch, in The Irish Times (26 Nov. 2011, Weekend, p.26). Not having been seen previously, the photo is possibly in Cronin’s own possession, given his relation to the reviewer.

|

| John Ryan, Cronin, Brian O’Nolan, Patrick Kavanagh & Tom Joyce

at the Sandymount Martello, 16 June 1954. (The 1st Bloomsday) |

| [See original and enlarged copy - as attached.] |

|

John Ryan’s 1954 Bloomsday Film |

| [ View Youtube Version - online. ] |

Delhi Djunket: A report on progress at the Ireland Literature Exchange and its collaboration with other languages through embassy connections is given by its director Sinéad Mac Aodha in Poetry Ireland (March/April 2008). The report includes an account of a trip to New Delhi made by three poets, Derek Mahon, Anthony Cronin and Anne Haverty, in Jan. 2008: ‘Three poets, Derek Mahon, Anthony Cronin and Anne Haverty, all read from their work to audiences who were both engaged and enchanted by their poems.Derek Mahon enthralled his listeners by reading some new poems which had been inspired by his recent visit to Goa and read from the works of other Irish poets, such as Louis MacNeice, Harry Clifton and John Montague. It is hoped that further invitations for Irish writers to India will follow in the wake of this success.’ (Mac Aodha, ‘Promoting Irish Literature Abroad’, in Poetry Ireland, March/April 2008 - available online; accessed 29.12.2024.)

John Banville: Cronin wrote to The Irish Times (20 Dec. 2001) arguing that Banville was mistaken about the nature Aosdána in supposing it is intended to support of “hungry” writers of members who do not ‘enjoy, like him, financial success and bidding him share his zeal with ‘those who have made same difficult and often dangerous vocational choice.’ In reply, John Banville wrote that ‘[t]he reason for [his]resignation was simple. I had for some years taken no active part in the proceedings of Aosdána, not because I disapproved of those proceedings, but because I was busy elsewhere, frequently out of the country, &c. It seemed, therefore, that the right and mannerly thing to do would be to resign.’ (See further under Banville - as supra.)

Justified winner: In a notice on the death of Anthony Cronin in The Irish Times (Sat., 31 Dec. 2017), Ronan McGreevy writes that, shortly before he died, Cronin had turned to Ms Haverty and said: “Have I done enough to justify?” He never finished the sentence, but she believed that he meant to ask if he had justified himself in his work. (Irish Times - online; accessed 31.01.2017.)

[ top ]