Life

| 1778-1803; b. 4 March, at 110 [now 124], St. Stephen’s Green, West, Dublin [prop. Glover’s Lane]; son of Viceroy’s physician, Dr. Robert Emmet, of Molesworth St., Dublin, and Elizabeth [née Mason], being seventeenth child born to them and fourth surviving; ed. at Oswald School, at Bride St., renowned for mathematics; afterwards at Samuel Whyte’s Grafton St. grammar school, and TCD [aetat. 15]; Emmet removed his name from the college books when [John Fitzgibbon] Lord Clare, then Chancellor of the University, made his visitation to search for United Irishmen in April 1798; warrant for his arrest, issued but not enforced while he remained in hiding in a secret chamber beneath the floor of his father’s study; visited his brother Thomas Addis Emmet [vars. Fort William; on the continent], and proceeded to Spain, Holland and Switzerland, then to Paris; joined in Paris by his brother; discussed Irish independence with Tallyrand; |

| returned to Dublin, 1802, intending to synchronise a rising with Napoleon’s invasion of Great Britain; set up a series of five depots, one in Patrick Street, nr. St. Patrick’s Cathedral; the rising, precipitated by explosion in arms factory, 16 July 1803, occurred on 23 July 1803 and failed because Michael Dwyer, Thomas Russell, and others did not join with their contingents; Emmet read out a proclamation: ‘A Band of Patriots, mindful fo their oath, and faithful to their engagement as United Irishmen, have determined to give freedom to their country, and a period to the long career of English oppression [...] We war not against property; we are against no religious sect; we war not against past opinions or prejudices; we war against English dominion’; advanced wearing his uniform of green coat, white breeches, and cocked hat with a small contingent of some hundred undisciplined men to take Dublin Castle, but dispersed on hearing of defensive preparations; |

| fled to Dublin Mts. [var. Wicklow hills] after the killing of Lord Kilwarden [Arthur Wolfe], a Lord Chief Justice and a relative of Wolfe Tone, with his nephew, but not before rescuing Miss Wolfe from the crowd, by report; captured by Major Henry Charles Sirr, 25 Aug., in hiding at Harold’s Cross at Palmer’s House under the assumed name of Hewitt, where he lingered to meet Sarah Curran; prosecuted by Wm. Conyngham Plunket (whom Emmet called ‘that viper my father warmed in his bosom’) before a bench comprising Lord Norbury, Baron George, and Mr. Baron Daly; prosecuted by the Attorney-General, Standish O’Grady, with the Solicitor General, James MacClelland [or Mac Lelland]; defended by Leonard McNally, with Peter Burrowes, Curran abstaining from his defence by reason of his compromised position; indicted for high treason, found guilty and sentence to be hanged, drawn and quartered, 19th Sept.; made stirring speech from the dock which became a classic of Irish political oratory; |

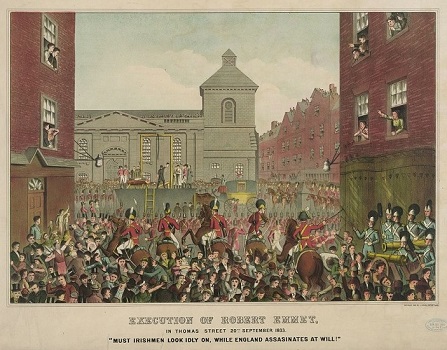

| executed on 20th Sept. outside St. Catherine’s Church in Thomas St.; reputedly declaring, ‘My Friends, I die in peace, and with a sentiment of universal love and kindness to all men’; decapitated while heart still beating; bur. secretly in an unknown grave, probably at the Royal Hospital at Kilmainham [now IMMA]; Emmet’s dock speech was taken down in court by McNally, son of the lawyer, author, and government agent; printed in Dublin Evening Post (20 & 22 Sept. 1803); copied by The Times and in the Morning Post (27th Sept. 1803); an unadorned version by William Ridgeway - a lawyer and for the crown and a printer in his own right, was published shortly after, being reprinted by him with accounts of other trials of Aug., Sept., and Oct. 1803 - including those of Kearney and Kirwan; a similar version printed in Walker’s Hibernian Magazine (Sept. 1803); |

| Emmet was dubbed ‘the Unfortunate Mr Emmet’ by H. B. Code, editor of The Warden, whose contemporary report on events as Insurrection of 23rd July, 1803 (1803) is regarded as a travesty by D. J. O’Donoghue and others; a version issued at the request ‘of his friends’ in 1807 bears Moore’s verse ‘‘Oh, Blame not the Bard’’, downplaying the supposed condemnation of France in the speech; Sarah Curran was expelled from her father’s house and sent to Cork by friends; she married a nephew of the Marquis of Rockingham in 1805, and died of T.B. two years after, at a Mediterranean naval station; Anne Devlin, Emmet’s devoted servant, dg. of a man imprisoned as a United Irishman, was arrested and tortured by the government; there is a modern monument-statue on St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin, by Jerome O’Connor, made in 1923 and finally installed in 1966 to a luke-warm govt. reception in de Valera’s Ireland; his execution is commemorated by a pavement-level plaque at St Catherine’s Church on Thomas St. where he died; another has been placed at the site of his arrest on Harold’s Cross Road, Dublin, erected by the Robert Emmet Assocation in 2003. CAB ODNB PI JMC DIB DIW DIH DIL RAF OCIL FDA |

[ top ]

|

(See further images in album - infra.) |

[ top ]

Note: A transcript of Emmet’s trial can be found in A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemeanours, compiled by T. B. Howell, Esq., FRS, FSA, and continued from the year 1783 to the present time: Thomas Jones Howell, Esq., Vol.X XVIII [being Vol. VII of the continuation] 42-44 George III - 1802-1803 (London: printed by Hansard for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Browne [&c.] 1820), as item 644: ‘Proceedings on the Trial of Robert Emmet, Esq. for High Treason; before the Court holden under Special at Dublin, on Monday, September the 19th: 43 George III a.d. 1803.’ [col.1098ff.] This edition includes annotations commencing with an extract from the Life of J. P. Curran by his Son W. H. Curran explaining ‘the alteration which took place in the appointment of counsel of the misguided subject of the present trial’. In a letter to Curran, Emmet speaks of his relations with his daughter: “I would rather have had the affections of your daughter in the back settlements of America, than the first situation this country could afford without them.” (col.1102) Emmet’s last letter to Richard Emmet immediately follows, including the sentence: “I have deeply injured you - I have injured the happiness of a sister that you love, and who was formed to give happiness to every one about her, instead of having her own mind a prey to affliction. Oh! Richard, I have no excuse to offer, but that I meant the reverse: I intended so much happiness for Sarah as the most ardent love could have given her. I never did tell you how much I idolized her [...] God bless you, my dear Richard, I am obliged to leave off immediately.” (Ibid, 1103.) Further remarks commending the courage of Emmet hours before his execution are likewise extracted from the Life of Curran by his son. The Howell edition has an appendix in the form of a document supposedly written by Emmet called “Account of the late plan of Insurrection in Dublin, and the Causes of its Failure” which is said to have been written by him before being ‘brought out to execution, in order to be forwarded to his brother Thomas Addis Emmet at Paris’ - according to a handwritten memorandum by ‘a gentleman who held a confidential situation in the Irish government’ which was attached to the copy from which the “Account” was described (all this in a footnote ending quoting an explanation made by the younger Curran Jnr. whose life of his father is given at the end as the source, following the initials of Emmet (“R.E.”) - viz., 2 Life of Curran, Appendix 515-522; here (col.1178-1184; end.) The treason trials of Henry Howley, John MacIntosh, Thomas Keenan, Daniel Remmond Lambert, throughout Sept. and October, follow separately. [Available at Google Books online - accessed 16.02.2012.]

[ top ]

Criticism| Monographs |

|

| Articles (sel.) |

|

Bibliographical details

R. R. Madden, Life [and Times] of Robert Emmet (Dublin: James Duffy 1847), xv, viii, 343pp., 12° [front. port.]; Do. [another edn.], with numerous notes and additions and a portrait on steel; also a memoir of Thomas Addis Emmet, with a portrait on steel (NY: P. M. Haverty 1857; rep. 1868), 328pp. [available as .pdf at Internet Archive - online] Do. [another edn.] (Glasgow, London: Washbourne 187-; Glasgow: Cameron, Ferguson & Co. 1902, 1909), 272pp. Also R. R. Madden, The Life and Times of Robert Emmet (Paris 1850) [in French edn.] See also The Life and Times of Robert Emmet, from authoritative sources [Irish Library, No 1.] (London John Ouseley Ltd. 1908), 96pp. [BL].Note: The Haverty edn. is prefaced by a page stating that publisher has deemed it necessary to eliminate some letters from the work written by Madden which are repeated in the adjoined Thomas Addis Emmet memoir of this edition, with other changes deemed necessary ‘in order to render the history more clear and connected’ - and, further, that footnotes have been added as ‘valuable additions’ from ‘recent authorities’, while the TA Emmet memoir has been ‘taken almost verbatim from Madden and Haines.’ (p.[ii].

[ top ]

| Thomas Moore | |

‘Oh! breathe not his name, let it sleep in the shade, But the night-dew that falls, though in silence it weeps, |

|

| —Irish Melodies, No. 1 (Dublin: Wm. Power 1807)] | |

| “The Death of Emmet, A.D. 180” by Brian O’Higgins |

|

|

[...] Go! hide your heads in guilty shame, unending, But come it will - the patriot’s vindication - Some day guilt receives its own red wages, |

| Rep. in Gill’s Irish Reciter: A Selection of Gems from Ireland’s Modern Literature, ed. J. J. O’Kelly (Dublin: M. H. Gill 1905), pp.152-54 [see full text under O’Higgins - as infra]. | |

Robert Southey: Emmet’s dock speech as reported in The Morning Post elicited an admiring paean from the English Romantic Southey: ‘[...] Emmet, No! / No withering curse hath dried my spirit up, / that I should now be silent, … that my soul / Should from the stirring inspiration shrink, / Now when it shakes her, and withhold her voice, / Of that divinest impulse never more / Worthy, if impious I withheld it now, / Hardening my heart. Here, here in this free Isle, / To which in thy young virtue’s erring zeal / Though wert so perilous an enemy, / Here in free England shall an English hand / Build they imperishable monument; / O, … to thine own misfortune and to ours, / By thine own deadly error so beguiled, / Here in free England shall an English voice / Raise up the mourning-song. For thou has paid / The bitter penalty of that misdeed; / Justice hath done her unrelenting part, / if she in truth be Justice who drives on, / Bloody and blind, the chariot of death. [... &c.]’ (See longer extract, attached.)

Thomas Moore - remarks on Emmet, in Life of Lord Edward Fitzgerald (quoted in R. R. Madden, Life of Emmet, 1847; new edn. NY: Haverty, 1857): ‘Mr. Moore, in his Life and Death of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, speaks of his young friend, and fellow student, in the following terms:“Were I to number, indeed, the men among all I have ever known, who appeared to me to combine in the greatest degree pure moral worth, with intellectual power, I should, among the highest of the few, place Robert Emmet. Wholly free from the follies and frailties of youth, - though how capable he was [6] of the most devoted passion, events afterwards proved, - the pursuit of science, in which he eminently distinguished himself, seemed at this time the only object that at all divided his thoughts, with that enthusiasm for Irish freedom, which in him was au hereditary, as well as national feeling; - himself being the second martyr his father had given to the cause. Simple in all his habits, and with a repose of look and manner indica ting but little movement within, it was only when the spring was touched, that set his feelings, and, through them, his intellect in motion, that he at all rose above the level of ordinary men. On no occasion was this more particularly striking than in those displays of oratory with which, both in the Debating and Historical Society, he so often enchaiued the attention and sympathy of his young audience. No two individuals, in deed, could be much more unlike to each other, than was the same youth to himself, before rising to speak and after; - the brow that had appeared inanimate, and almost drooping, at once elevating itself to all the consciousness of power, and the whole countenance and figure of the speaker assuming a change as of oue suddenly inspired. Of his oratory, it must be recol lected, I speak from youthful impressions ; but I have heard little, since that appeared to me, of a loftier, or what is a far more rare quality in Irish eloquence, purer character; and the effects it produced, as well from its own exciting power, as from the susceptibility with which his audience caught up every allusion to passing events, was such as to attract at last the serious attention of the fellows; and, by their desire, one of the scholars, a man of advanced standing and reputation for oratory, came to attend our debates, expressly for the purpose of answering Emmet, and endeavouring to neutralize the im pressions of his fervid eloquence. Such in heart and miud was another of those devoted men, who, with gifts that would have made the ornaments and supports of a well regulated community, were driven to live the lives of conspirators, and die the death of traitors, by a system of government which it would be difficult even to think of with patience, did we not gather a hope, from the present aspect of the whole civilized world that such a system of bigotry and misrule can never exist again.”’ (Madden; Havert Edn., NY 1857, pp.6-7.)

Thomas Moore (Memoir, ed. Lord Russell, 1853): ‘[...] This youth was Robert Emmet, whose brilliant success in his college studies, and more particularly in the scientific portion of them, had crowned his career, as far as he had gone, with all the honours of the course ; while his powers of oratory displayed at a debating society, of which, about this time (1796-7), I became a member, were beginning to excite universal attention, as well from the eloquence as the political boldness of his displays. He was, I rather think, by two classes, my senior, though it might have been only by one. But there was, at all events, such an interval between our standings as, at that time of life, makes a material difference ; and when I became a member of the debating society, I found him in full fame, not only for his scientific attainments but also for the blamelessness of his life and the grave suavity of his manners.’ [Cont.]

Thomas Moore (Memoir, 1853) - cont: Moore recounts his conversation with Emmet following the publication of his [Moore’s] letter “To the Students of Trinity College” on the political issues of the day - viz., Catholic emancipation: ‘A few days after, in the course of one of those strolls into the country which Emmet and I used often to take together, our conversation turned upon this letter, and I gave him to understand it was mine; when, with that almost feminine gentleness of manner which he possessed, and which is so often found in such determined spirits, he owned to me that on reading the letter, though pleased with its contents, he could not help regretting that the public attention had been thus drawn to the politics of the University, as it might have the effect of awakening the vigilance of the college authorities, and frustrate the progress of the good work (as we both considered it) which was going on there so quietly. Even then, boyish as my own mind was, I could not help being struck with the manliness of the view which I saw he took of what men ought to do in such times and circumstances, namely, not to talk or ivrite about their intentions, but to act. He had never before, I think, in conversation with me, alluded to the existence of the United Irish societies in college, nor did he now, or at any subsequent time, make any proposition to me to join in them, a forbearance which I attribute a good deal to his knowledge of the watchful anxiety about me which prevailed at home, and his foreseeing the difficulty which I should experience from being, as the phrase is, constantly “tied to my mother’s apron-strings”; in attending the meetings of the society without being discovered.’ (Quoted in Stephen Gwynn, Thomas Moore, London: Macmillan 1905, pp.10-11.)

| Moore’s Poems on the theme of Robert Emmet and Sarah Curran |

He Who Adores Thee has Left But the Name ... She is Far From the Land .... |

[ top ]

Catherine Wilmot (letter to her brother, March 1802): ‘We have lately become acquainted with Robert Emmett [sic], who, I dare say you have heard of … His face is uncommonly expressive of everything youthful and everything enthusiastic, and his colour comes and goes rapidly, accompanied by such a nervousness of agitated sensibility, that in his society I feel in a perpetual apprehension lest any passing idle word shou[l]d wound the delicacy of his feelings.’ (Quoted in Colm Tóibín, ‘Emmet and the historians [what the epaulets were for]’, in The Dublin Review, Autumn 2003, pp.121-22.)

S. T. Coleridge: In his letter to the Beaumonts, Coleridge compares Emmet to himself at 24, at which age he was retiring from revolutionary politics ‘fully awake to the inconsistency of my practice with the speculative Principles’: ‘Alas! Alas! unlike me, he did not awake! the country, in which he lived, furnished far more plausible arguments for his active Zeal than England could do […] and in this mood the poor young Enthusiast sent forth that unjustifiable Proclamation,one sentence of which clearly permitted unlimited assassination - the only sentence, beyond all doubt, which Emmett [sic] would gladly have blotted out with his Heart’s Blood […] This moment it was a few unweighed words of an impassioned Visionary, in the next it became the foul murder of Lord Kilwarden! […] I was preserved from Crimes that it is almost impossible not to call Guilt!’ (Earl Leslie Griggs, ed., Collected Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 6 vols., Clarendon Press, 1956-71, Vol. 2, pp.998-1,005; quoted in Timothy Webb, ‘Coleridge and Robert Emmet’, in Irish Studies Review, 8, 3 (2000, pp.304-24; p.315.)

John T. Campion, “Emmet’s Death” [‘“He dies to-day”, said the heartless judge, / Whilst he sate him down to the feast, / And a smile was upon his ashy lip / As he uttered a ribald jest [...] “He dies to-day”, said the jailer grim, / Whilst a tear was in his eye; / “But why should I feel so grieved for him? / Sure, I’ve seen so many die!” [...] “He dies to-day”, thought a fair, sweet girl - / She lacked the life to speak, / For sorrow had almost frozen her blood / And white were her lip and cheek [...].’ (In Justin McCarthy, ed., Irish Literature, 1904, Vols. 1-2, p.463.)

| Charles Robert Maturin, Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) contains a footnote on the death of Lord Kilwarden in the Emmet Rising appended to a passage dealing with the dismemberment and assassination of the Supreme [Dominican authority] - see further under Arthur Wolfe - infra. |

[ top ]

Charles G. Duffy, ‘Thomas Moore’ (The Nation 1842), writes: ‘he was in the junior and senior Historical Societies with Emmett [sic] - heard his eloquence, and possessed his intimacy, if not his friendship. Emmett’s mind must have greatly influenced him. He “used sometimes”, said Moore, “sit by me”, when playing the Irish airs from Bunting; “and I remember one day his starting up as from a reverie when I had just finished playing that spirited tune called The Red Fox, and exclaiming, “Oh, that I were at the head of twenty thousand men marching to that air!”’ (Quoted in Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, 1991, Vol. 1, p.1,252.) Note more extensive quotation ascribed to Thomas Moore’s account of his indebtedness to Bunting’s collection: ‘there elapsed no very long time before I was myself the happy proprietor of a copy of the work and, though never regularly instructed in music, could play over the airs with tolerable facility on the pianoforte. Robert Emmett [sic] used sometimes to sit with me when I was thus engaged; and I remember one day his starting up as from a reverie, when I had finished [... &c.]’ (Quoted in Bridget O’Toole, review of A. N. Jeffares & Peter Van der Kemp, ed., Irish Literature: The Eighteenth Century, in Books Ireland, April. 2006, p.78.)

R. R. Madden, ‘The poets of antiquity were his companions, its patriots his models, and its republics his admiration.’ (The United Irishmen: Their Lives and Times, 3rd series, 2nd edn., London 1860, p.287.) Further, Emmet’s mind ‘was so imbued with the finest forms of ancient art and most perfect images of the orator of Greece and Rome, that he seems to have made for himself an ideal existence of their excellencies, and to have lived in the past as if he belonged to it, and in the present as if he were in it but not of it.’ (ibid., 478.) See also Madden’s remarks the concluding sanction in Emmet’s in his dock speech, ‘The time in my opinion has arrived’ (in Emmet, 1840). Madden further notes that Emmet wrote a piece called “Arbor Hill” in invisible ink in 1797.

Note: Life [and Times] of Robert Emmet, with numerous notes and additions and a portrait on steel; also a memoir of Thomas Addis Emmet, with a portrait on steel (NY: P. M. Haverty 1857; rep. 1868), 328pp. is available as a PDF at Internet Archive - online]

W. E. H. Lecky, The History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century (London: Longmans, Green & Co. 1892), Vol. V: ‘The short rebellion of Emmet, in 1803, was merely the last wave of the United Irish movement, and it was wholly unconnected with the Union and with the recent disappointments of the Catholics. It was suppressed without difficulty and without any acts of military outrage, and it a least furnished the Government with a gratifying proof that the Union had not broken the spirit of loyalty in Dublin, for the number of yeomen who enlisted there, was even greater than in 1798 [as stated in a letter of Grattan to Fox]’. (p.466). Lecky’s Table of Contents chapter-summary reads: Emmet’s rebellion - loyalty shown in Dublin - to government - Grattan’s letter.’

Denis Murphy, LLD, MRIA, A Short History of Ireland for Schools (Dublin: Fallon & Co. n.d.) - EMMET’S ATTEMPT: In spite of the failure of the rising of 1798, some who saw that a great struggle was about to take place between England and France, hoped it would turn out to be “Ireland’s Opportunity”. Among those was Robert Emmet, a younger brother of Thomas. He had received encouragement from Bonaparte, who was then meditating an invasion of England. On his return to ireland he sought out those who had taken part in the former rising. Depots of arms were formed. His plan was to surprise Dublin Castle, seize on the authorities, and give the signal for a general rising. July 23 was the day fixed for the outbreak. / FAILURE OF THE ATTEMPT: When the day came, the arrangements for the rising were not completed. The Wicklow men had not come; the Kildare men were told that the rising was deferred. About 300 Wexford men had come, but they were without orders. At 8 o’clock at night only 80 met at the appointed place in Marshalsea Lane, and being told that the troops were on their way to attack them, they marched at once upon the Castle. On their way through Thomas Street they began pillaging the shops. Lord Kilwarden, a humane man, who, with his nephew [sic], was passing by in a coach, was killed. Emmet, seeing that those round him thought only of plunder, gave up all as lost and withdrew. When the military came up, the insurgents fled in different directions. The next day a search was made. Arms and munitions were discovered, printed proclamations too, calling on the people to take up arms for the establishment of a free and independent republic in Ireland. EMMET’S EXECUTION: Emmet fled to Wicklow. A few days after he returned to see for the last time a daughter of Curran, to whom he was betrothed. He was arrested August 25th, and on September 19th he was brought to trial on a charge of high treason. Plunket, counsel for the Crown, who had denounced the Union, spoke with much bitterness against the prisoner. The trial lasted but one day; at midnight the jury brought in the verdict of guilty. Before the sentence was passed, he made the eloquent speech in which he asked that “his memory should be left in oblivion and his tomb remain uninscribed, until other times and other men could do justice to his character. When his country took her place among the nations of the earth, then, and not till then, should his epitaph be written’ He was executed the next morning on Thomas Street. Twenty of those who were arrested were tried at the same time, of whom seventeen were hanged. Of the others who had taken part in the rising, some were imprisoned, and several escaped to France.’ (p.146.)

[ top ]

Patrick Pearse: ‘No failure, judged as the world judges these things, was ever more complete, more pathetic than Emmet’s. And yet he has left us a prouder memory than the memory of Brian victorious at Clontarf or of Owen Roe victorious at Benburb. It is the memory of a sacrifice Christ-like in its perfection.’ (Commem. speech in New York, 1914; Political Writings, Talbot Press [n.d.], p.69; quoted in Joseph Lynch, MA Diss., UU 2003.) ‘And his death was august. In the great space of Thomas Street an immense silent crowd; in front of Saint Catherine ’s Church a gallows upon a platform; a young man climbs to it, quiet, serene, almost smiling, they say - ah, he was very brave; there is no cheer from the crowd, no groan; this man is to die for them, but no man dares to say aloud “God bless you, Robert Emmet”. Dublin must one day wash out in blood the shameful memory of that quiescence. [...] He was saying “Not yet” when the hangman kicked aside the plank and his body was launched into the air. They say it swung for half-an-hour, with terrible contortions, before he died. When he was dead the comely head was severed from the body.’ (Political Writings, 1922, pp.70-71; quoted in Dominic Manganiello, Joyce’s Politics, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980, p.145.)

James Joyce: ‘Unlike Robert Emmet’s foolish uprising or the impassioned movement of Young Ireland in ’45, the Fenianism of ’67 was not one of the usual flashes of Celtic temperament that lighted the shadows for a moment and leave behind a darkness blacker than before.’ (“Fenianism”, 1907 [Piccolo del Sera, Trieste]; rep. in Critical Writings, 1966, p.188; see further under Joyce, Quotations, infra.)

Stephen Gwynn, Robert Emmet: A Historical Romance (1909), ending: ‘Sundered head and body lie today, no man knows where: to trace them has baffled many searchers. But the spirit and the life which moved them are abroad upon the world, and have been for a hundred years, defying the violence of power, the authority of dominion. Not yet can the epitaph be written; but till it be, Robert Emmet the defeated, the deceived, the undismayed and undespairing, animates for ever the hope in which he died: and she, that tender one, crazed and shattered, moves sadly in his orbit, quickening all hearts with an eternal truth for love forgone.’ (‘Reviews’, in The Irish Book Lover , Vol. I, No. 5, Dec. 1909, 58.)

P. W. Joyce, A Child’s History of Ireland (Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son; London: Longmans, Green and Co. 1910): ‘Three years after the Union there was one other attempt at insurrection, which however was confined to Dublin. Several of the leaders of the United Irishmen were at this time in Paris; and as they had some reason to expect aid from Napoleon, they projected a general rising in Ireland. One of their body, Robert Emmet, a gifted, earnest, noble-minded young man, twenty-four years of age, returned to Dublin in 1802, to carry out the arrangements, and expended his whole private fortune in secretly manufacturing pikes and other arms. / His plan was to attack Dublin Castle and the Pigeon House fort; and he had intended that the insurrection should take place in August 1803, by which time he calculated the invasion from France would come off; but an accidental explosion in one of his depots precipitated matters. News came in that the military were approaching; whereupon, in desperation, he sallied form his depot in Marshalsea-lane, into Thomas-street and towards the castle with about 100 men. They city was in an uproar; disorderly crowds gathered in the streets, and some stragglers, bent on mischief and beyond all restrain, began outrages. Meeting the chief justice, Lord Kilwarden, a good man and a humane judge, they dragged him from his coach and murdered him. When the news of this outrage was brought to Emmet, [477] he was filled with horror, and attempted in vain to quell the mob. Seeing that the attempt on the castle was hopeless, he fled to Rathfarnham; and might have escaped, but he insisted on remaining to take leave of Saran Curran, daughter of John Philpot Curran, to whom he was secretly engaged to be married. He was arrested by Major Sirr on the 25th of August at a house in Harold’s Cross; and soon after was tried and convicted, making a short speech of great power in the dock. On the next day, the 20th of September 1803, he was hanged in Thomas-street.’ (pp.477-78).

[ top ]

Seamus MacManus, The Story of the Irish Race: A Popular History of Ireland, by Seamus MacManus, assisted by several Irish scholars (NY: Irish Publishing Co. [2nd edn.] 1921): ‘Saturday, the 23rd of July, was the day arranged for the Rising in Dublin, in which the Wicklow, Kildare and Wexford men were to assist.’ Quotes Emmet’s account of the treacherous information that the rising was ‘off’ which sent the Kildare men back home from Costigans Mills, ‘the grand place of assembly‘. Thomas Addis Emmet, in Paris, is disappointed enough by the French inaction to call Napoleon ‘the worst enemy that Ireland ever had’. ‘As for his brother, Robert, when he say the blood of Lord Kilwarden stain the stones of that Dublin street, he dispersed his followers, and sought out Michael Dwyer in the Wicklow hills. Dwyer and his men (whose failure to present at the rendezvous was due to a gross dereliction of duty on the part of the man charged with the message for them) urged that an attempt should be made on the neighbouring towns, but Emmet determined to do nothing more until the promised French aid had arrived. To expedite its coming he send Myles Byrne with an urgent message to his brother, Thomas Addis. / Before Myles Byrne had arrived in Paris, Robert had been arrested by Major Sirr at Harold’s Cross, to whose dangerous neighbourhood he had been drawn by an overpowering desire to see once more his “bright love” the exquisite Sarah Curran. On the 19th of September, two days after Byrne had delivered his message to Thomas Addis, Robert Emmet stood in the dock in Green Street, uttering that immortal oration which no one who loves great poetry or high passion can ever read without all that is best in him flaming up at the contact of its fire. On the 20th of September the sacrifice was consummated. The brave youth was publicly beheaded on a Dublin street.’ (Authorities: Madden, Lives of the United Irishmen; Myles Byrne’s Memoirs; Thomas Addis Emmet, The Emmet Family; O’Donoghue, Life of Robert Emmet; Mitchel, History of Ireland. (pp.537.)

M. J. MacManus, Irish Cavalcade 1550-1850 (Macmillan 1939): ‘Let No man Write My Epitaph’ (1803), p.220-21, prefaced by a note: ‘Emmet’s speech before execution is as familiar to Irish schoolboys as that of Lincoln at Gettysburg is to the youth of America.’. The excerpt begins ’My lord, you are impatient for the sacrifice’ and ends ’let my epitaph be written.’

Helen Landreth, The Pursuit of Robert Emmet (Dublin: Browne & Nolan, 1949) [Richview Press], 427pp., index; CONTENTS by Chaps. Background [2 sects. incl. Birth of United Irishmen]; Pitt’s Weapons [4 sects. incl. Intimidation; Informers; Orange Order]; Initiation to Warfare [6 sects. incl. Expelled from TCD; Red Harvest of 1798]; Interlude [2 sects., in France]; Emmet Prepares for Another rising [8 sects. incl. Castle Watches; Love and War; Explosion in Patrick St.; Thomas Russell]; July 23, 1803 [4 sects. incl. Prelude; Action; Aftermath; Rising Elsewhere]; The Hunt [4 sects., incl. Mountains; Kildare; Harold’s Cross; Arrests]; Emmet’s Capture and Ordeal [8 sects. incl. Arrest; Plans to Escape; Major Sirr Raids Priory; Russell Helps Emmet; Into the Depths; Myles Byrne Reaches Paris]; The Trial of Robert Emmet [4 sects in. Crown’s Case; Crown Witnesses; Calumny; Emmet Answers]; Execution [2 sect. incl. Scaffold in Thomas St.]; Using the Rising [2 sects. incl. Pitt’s Fight for Office]; Index. The author an American, and dedicated to a young American soldier in World War II (Richard Landreth Parker) because ‘the things they fought for were the same, love of justice, belief in democracy’ and written out of ‘devotion to those same principles’; gallant, tender, and idealistic personality’ of Emmet emerged amid State Papers; ‘I realised I had stumbled on a great mystery; for reason that will become apparent, the true story of Robert Emmet’s insurrection [...] had never been told, and for generations efforts had been made to keep it a secret [...] secret and confidential official letters spoke of hundreds of men having been engaged in the fighting in Dublin, of Emmet’s preparations having been extensive and costly [...] a simultaneous insurrection in the North of Ireland had been frustrated by the craftiness of a spy posing as a rebel leader [...] all knowing to under-secretary Mr Alexander Marsden [...] taken great pains that the rebels should not be frightened into giving up their plans for war [...] Robert Emmet tricked into revolt in 1803 [...; cont.].[ top ]

Helen Landreth (The Pursuit of Robert Emmet, 1949) - cont.: Sir Bernard Burke told Dr. Thomas Emmet that he had read a document in the State Papers from Pitt asking Marsden to foment a rebellion; Emmet tricked by agent to return to Ireland from Paris; a sealed box disappeared; she continues, it was an exciting moment for me when, sitting in the Search Room of the Irish State Paper Office in Dublin I realised that the papers I was then turning over were some of the very ones Dr. Emmet had thought destroyed. She argues that Pitt made use of the fomented rising to return to office in 1804. The narrative is detailed, well-supplied with documentary evidence, and in parts novelistic [‘noose swayed gently in the mild September air’]. There is an astute commentary on the variance of version of the dock speech, in ftn. at p.352. Emmet’s neck was not broken by the fall and he struggled at the end of the rope. His head was severed with a common knife. Further Recounts that a death mask was made by the artist George Petrie on the night of his death (pp.372-73); Petrie removed the head from the thin penal coffin in the entry of Kilmainham, thinking he could work better at home, and when he returned the coffin and body were gone, so he held on to the head. Copies of the death mask in the National Gallery and National Museum. Stephen Gwynn remarks in a dust-jacket review, ‘This work is of real importance. No student of the period, which is crucial for all modern Irish history, can neglect it.’

W. B. Stanford, Ireland and the Classical Tradition (1984), writes: ‘At his maiden speech to the Historical Society, Emmet discoursed on freedom and “proceeded to portray the evil effects of the despotism and tyranny of the governments of antiquity and most eloquently depicted those of Greece and Rome.”’ (Citing R. R. Madden, Life of Robert Emmet, Dublin 1847, p.6; cf. Dagg, History of College Historical Society, Cork 1969, p.95.)

Cathal G. Ó Hainle, ‘“The Inalienable Right of Trifles”: Tradition and Modernity in Gaelic Writing Since the Revival’, in Éire-Ireland (Winter 1984): ‘Pearse’s verse is the first truly modern verse in Gaelic in that the speaker in most of his poems voices concerns which are intensely personal. [... ] Instead of allowing the strict requirements of the traditional form to dominate, he uses freer versions which he could better control and more easily bond with his subject-matter.’ Further: ‘Pearse’s slender output pointed the direction that Irish poetry could have taken. Unfortunately, poetic talent in Gaelic was extremely thin on the ground in the 1920s and 1930s and Pearse can hardly be said to have had a successor in that period.’ (p.62.) Further: ‘As a pioneer in prose fiction he met with some success. He had seen that the early prose writers of the revival had been too heavily influenced by folktale models [...] Pearse urged again and again that the way forward was through the rejection of the folktale model and the adoption of the European short story.’ (Ibid., p.63; all quoted in Joseph Lynch, MA Diss, UU 2003.)

Joep Th. Leerssen, Mere Irish & Fíor Ghael, 1986, p.435, identifying Moore’s biography of Lord Edward as the instrument which established his place in the national hagiology [And note, mis-orthography, Robert Emmett, sic].

[ top ]

Norman Vance, commenting on Moore’s “Oh, Breathe Not His Name”: ‘[Emmet’s name is both] absorbed into and silently eradicated by unvoiced national sentiment, participating in the parody of life-renewing martyrdom that characterises national as well as religious ideologies.’ (Irish Literature: A Social History, Basil Blackwell 1990, p.106; quoted in Naomi Doak, MA Essay, 2002-03.)

Stephen Watt, Joyce, O’Casey, and Irish Popular Theatre (1991), comments on the melodrama, Robert Emmet (Chicago 1884), characterising it as the earliest of the political-melodrama genre in popular Irish drama.

Timothy Webb, ‘Their [the English Romantics’] concern for, and ability to identify with, Emmet may also owe more than a little to the fact that, like them, he was the product of a middle-class background and of a university education. Emmet’s insurrect was the result of political factors which were specifically Irish, yet it was partly inspired by the momentum which had been generated during the French revolutionary period and it was premised on the hope of an intervention of the French themselves. For these English observers it might almost have seemed as if a chapter of the French Revolution had been translated into English.’ (p.311; see notes, infra.)

Colm Tóibín, ‘Emmet and the historians [what the epaulets were for]’: A review-essay published in The Dublin Review, No. 12 (Autumn 2003): ‘[...] Hardly any letters written by Robert Emmet survive; there is no autobiography; there are few contemporary references to him, although there are many to his older brother, Thomas Addis Emmet. Robert Emmet appears, it seems, from nowhere, with fire in his eyes and nothing in his head except abstract ideas of liberty. He is out of Stendhal more than he is out of history. Thus he is fodder not only for songs and stories and patriotic speeches that sanctify his glory, but also for mockery by writers such as James Joyce and Denis Johnston (and indeed Borges) who saw the comic possibilities of such sanctity, and for Irish historians, crudely called ‘revisionist’, who sought to re-examine the shibboleths surrounding Irish nationalism. Laughing at Emmet was one of the best ways available of killing your Irish nationalist father.’ (For full text, see infra.)

[ top ]

Quotations

Dock Speech: ‘[...] My Lords you are impatient for the sacrifice. The blood which you seek is not congealed by the artificial terrors which surround your victim - it circulates warmly and unruffled through the channels which God created for noble purposes, but which you are bent to destroy, for purposes so grievous that they cry to heaven. But yet be patient! I have but a few more words to say - I am going to my cold and silent grave - my lamp of life is nearly extinguished - my race is run - the grave opens to receive me, and I sink into its bosom. I have but one request to make at my departure from this world, it is - the charity of its silence. Let no man write my epitaph; for as no man who knows my motives dare now vindicate them, let not prejudice or ignorance asperse them. Let them and me rest in obscurity and peace; and my tomb remain uninscribed and my memory in oblivion until other times and other men can do justice to my character. When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then, and not till then, let my epitaph be written. I have done.’ [End; see full text - as attached.]

Dear Sarah: ‘My dearest Love, I don’t know how to write to you. I never felt so oppressed in my life as at the cruel injury I have done you. I was seized and searched with a pistol over me before I could destroy your letters. They have been compared with those found before. I was threatened with having them brought forward against me in Court. I offered to plead guilty if they would suppress them. This was refused. My love, can you forgive me? / I wanted to know whether anything had been done respecting the person who wrote the letter, for I feared you might have been arrested. They refused to tell me for a long time. When I found, however, that this was not the case, I began to think that they only meant to alarm me; but their refusal has only come this moment, and my fears are renewed. Not that they can do anything to you even if they would be base enough to attempt it, for they can have no proof who wrote them, nor did I let your name escape me once. But I fear they may suspect from the stile [style], and from the hair, for they took the stock [Emmet’s cravat into which Sarah had sewn a lock of her hair] from me, and I have not been able to get it back from them, and that they may think of bringing you forward. / I have written to your father to come to me tomorrow. Had you not better speak to himself tonight? Destroy my letters that there may be nothing against yourself, and deny having any knowledge of me further than seeing me once or twice. For God’s sake, write to me by the bearer one line to tell me how you are in spirits. I have no anxiety, no care, about myself; but I am terribly oppressed about you. My dearest love, I would with joy lay down my life, but ought I to do more? Do not be alarmed; they may try to frighten you; but they cannot do more. God bless you, my dearest love. I must send this off at once; I have written it in the dark. My dearest Sarah, forgive me.’ (Sept. 1803; see “Remembering Robert Emmet” web site [link].)

| Dock Speech: |

‘[...] God forbid that I should see my country under the hands of a foreign power. [...] If the French come as a foreign enemy, Oh, my countrymen! meet them on the shore with a torach in one hand - a sword in the other - receive them with all the destruction of war - immolate them in their boats before our native soil shall be polluted by a foreign foe. If they succed in landing, fight them on the strand, burn every blade of grass before them, as they advance; raze every house; and if you are driven to the centre of your country, collect your provisions, your property, your wives and your daughters, form a circle around them - fight while two men are left, and when one remains let that man set fire to the pile, and release himself and the families of the his fallen countrymen form the tyranny of France. [...] Deliver my country into the hands of Frances! - Look at the proclamation - Where is it stated? - Is it in that part, where the people of Ireland are called upon to show the world, that they are competent to take their place among the nations? - that they have a right to claim acknowledgement as an independent country, by the satisfactory proof of their capability of maintaining their independence? - by wresting it from England, with their own hands? Is it in that part where it is stated, that the system has been organised witin the last eight months, without the hope of foreign assistance, and whcih the renewal of hostilities accelerated? Is it in that [1173] part, which desires England not to create a deadly national antipathy between the two countries? |

| —See “Trial of Robert Emmet, Esq., for High Treason [... &c.]”, in A Compete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason and Other Crimes and Misdemeanours, compiled by T. B. Howell, [...] continued from the year 1783 [... by] Thomas Jones Howell, Vol. XXVIII (London: printed by Hansard for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Browne [... &c.] 1820) [Available at Google Books online - accessed 16.02.2012.] (See also the received version of Emmet’s dock speech in Irish national tradition as given in T. D. Sullivan, ed., Speeches from the Dock, ed. T. D. Sullivan, et al. (Dublin: M. H. Gill 1909) - attached. |

[ top ]

References

Justin MacCarthy (Irish Literature, 1904), selects Last Speech and Lines Written on Arbor Hill Burying-Ground [of 1798 Insurgents], ‘No rising column marks the spot/Where many a victim lies/But oh! the blood which here has streamed/To Heaven for justice cries. &c.’

Stephen Brown, Ireland in Fiction (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), lists Stephen Gwynn, Robert Emmet (Macmillan 1909) [with maps of Dublin 1803], a narrative with Quigley [Coigly], Russell, Hamilton, Dwyer, all accurately drawn, and prominent place given to the romance of Emmet and Sarah Curran [Brown]. Other fictions listed under Emmet in Brown’s appendix are Mathias Bodkin, True Man and Traitor (Duffy 1910); Robert Thynne, Ravensdale (1873), Unionist viewpoint; George Gilbert [pseud. of Miss Arthur], The Island of Sorrow (Longman 1903), portrait not lacking in sympathy though the theatrical and inconsiderate character of his aims insisted on [Brown]’.

Frank O’Connor, ed., Book of Ireland (London: Collins 1979), gives extract from the Dock Speech.

Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English: The Romantic Period, 1789-1850, 2 vols (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980): Vol. 1, p.135, cites poems on and to Emmet collected by Madden (Literary Remains of the United Irishmen, p.148), including those by Moore, Atkins (in Pilgrims of Erin), Emmet’s sister Mrs Holmes and his niece Mrs. Conyngham, and also an anonymous lament: ‘The joy of life lies here/Robert A Roon/All that my soul held dear/Robert A Roon.’ (Madden, p.250-51; also in Life and Times, 1847).

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 1: p.934, gives Emmet’s dock speech, in Ridgway’s version, and discusses the circumstances in which it was composed and spoken. ‘The version given is free of the rounded periods characteristic of the better-known late nineteenth-century versions’ [ed.] The biog. note speaks of ‘the collapse of his attempted coup d’etat’ [959]. FDA2 has remarks at 77, 267, 277, 292, 339, 683, 694, 799, 833, 834, 841, 854, 932n, 973, 974, 990, 1016n. [See also under C. G. Duffy, infra.]

Kevin Rockett, et al., eds, Cinema & Ireland (1988), Bold Emmet, Ireland’s Martyr (Olcott, 1914); when show at the Rotunda the authorities had with withdrawn claiming it was interfering with recruiting. Bosco Hogan played Emmet in the film, Anne Devlin (1984). [See page index, and Devlin, supra].

UUC Library holds Robert Emmet: The insurrection of July 1803 (Belfast: HMSO. 1976) [facs.]; Nellie Maher, Robert Emmet: his two loves [PR6063.A25R6]; Léon Ó Broin, The Unfortunate Mr. Robert Emmet (Dublin: Clonmore & Reynolds; London; Burns Oates & Washbourne 1958); Helen Landreth, The Pursuit of Robert Emmet (Dublin: Browne & Nolan 1949); Caesar Litton Falkiner, Essays relating to Ireland: Biographical, Historical and Topographical (London; NY: Longmans, Green & Co 1909); Stephen Gwynn, Robert Emmet: A Historical Romance (London: Macmillan 1909); Louise Imogen Guiney, Robert Emmet: A Survey of his Rebellion and of His Romance (London: Nutt 1904); Richard Robert Madden, The Life and Times of Robert Emmet (Glasgow: Cameron, Ferguson & Co. 1902; Glasgow; London: Washbourne 1844); Michael James Whitty, Robert Emmet, I: The Cause of His Rebellion; II: The cause of Its Failure (London: Longmans, Green, 1870); John Finegan, Anne Devlin: Patriot and Heroine: Her Own Story of Her Association with Robert Emmet (Dublin: Elo Publications 1992); Geraldine Hume, Robert Emmet, The Insurrection of 1803 (Belfast: HMSO/PRONI 1976); Micheál Mac Liammóir, I must be Talking to My Friends: Ireland Seen through the Eyes of Her Writers (London: Argo, 1966). audio-disc.

Working Class Movt. Library (51 The Crescent, Salford, U.K. M5 4W) holds Richard R. Madden, The Life and Times of Robert Emmet (Dublin: James Duffy 1846); William Ridgeway, A Report of the Trial of Robert Emmet (1803), in “Scully’s Irish Catholics’ Advice”; Thomas Davis, ed., The Speeches of the Rt. Hon. John Philpot Curran, With Memoir (Dublin: James Duffy 1845); William Henry Curran, Life of Rt. Hon. John Philpot Curran, 2 vols. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable 1822); Charles Phillips, Curran and His Contemporaries (Edinburgh: Wm Blackwood 1851), all as part of the library of T. A. Jackson (1867-1955) [See online.].

Sundry Catalogues: BELFAST CENTRAL LIBRARY holds Trial of Robert Emmet for High Treason (1803) N4717; see also extensive listings in the library’s subject index. HYLAND BOOKS (Oct. 1995), lists The Trial of Edward Kearney for High Treason, Dublin 1803, 47pp. EMERALD ISLE BOOKS (1995) lists Emmet’s Insurrection of 1803, The Opinion of an Impartial Observer, concerning the late Transactions in Ireland [2nd edn.] (Dublin: John Parry 1803), with abstract of trial of John Donnelly on 10 Sept. 1803 appended.

[ top ]

|

Thomas Russell, in his dock-speech after death-sentence was passed, called Emmet “[the] youthful hero, a martyr in the cause of liberty, who has just died for his country. To his death I look back, even in this state, with rapture.” (See Peter Linebaugh, ‘“Is This the Place?”: On the Bicentennial of the Hanging of Thomas Russell’, in Counterpunch, ed. Alexander Cockburn & Jeffrey St. Clair, 21 Oct. 2003 [infra]).

W. H. Maxwell’s Erin Go Bra, or Irish Life Pictures, 2 vols. (London: R Bentley 1859) contains a story devoted to Robert Emmet. (See Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English: The Romantic Period, 1789-1850, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980, Vol. 1, p.136.)

Birthplace: Emmet’s birthplace at 110 St. Stephen’s Green (later 124), was established by David A. Quaid in a pamphlet [brochure] of 1902 Dublin 1902. (See C. L. Falkiner, Papers Relating to Ireland, c.p.40.) Note further: Adjacent to York St., the actual house was destroyed when houses on Glover’s Lane collapsed.

Dock speech: Emmet’s dock speech and its waiving of an patriotic epitaph (‘Let no man write my epitaph [...] ) taken as the basis for the name of the Emmet Monument Association (1857), being the primitive form of the IRB; also parodied in James Joyce’s version of the execution of the patriot in Ulysses.

Death masks: R. R. Madden writes, ‘A death mask of Emmet taken by George Petrie, who also made a sketch at the trial, was sold on Liffey St. and bought by T. A. Emmet’; ‘the other representation of the cast taken after death by Petrie of the notorious Jemmy O’Brien I have had placed in juxtaposition with that of Robert Emmet to show the striking contrast of the two countenances.’ (Robert Emmet, 1840.)

[ top ]

Watercolour portrait after sketch done at his trial, anon., presented to NGI by HB Boyle, C.B.; also Robert Emmet portrayed by Fred O’Donovan in Lennox Robinson’s The Dreamers, painted by James Sleator (1999-1949), belonging to the Abbey Company.

Injured sister: Emmet wrote to Sarah’s brother from Kilmainham Prison, ‘I have injured the happiness of a sister that you love [...] Oh Richard! I have no excuse to offer, but that I meant the reverse; I intended as much happiness for Sarah as the most ardent lover could have given her. I never did tell you how much I idolised her.’ (See “Remembering Robert Emmet” web site [link]

Patrick Maher, one of those executed by the British judicial administration in ireland during 1919-21, spoke these words in the scaffold: ‘My soul goes to God at seven o’clock and my body goes to Balgally when Ireland shall be free.’ Maher, with others incl. Kevin Barry, was re-interred in accordance with his wishes in Nov. 2001.

Commemoration (Dublin, 20 Sept. 2003): “The Republic of Letters”, a recital of poetry, prose and music was given in Kilmainham Gaol at the bi-centenary of the Emmet’s execution. The event was compèred by Kevin Whelan with poems of Florence Wilson, Seamus Heaney, Derek Mahon, Thomas Kinsella and Medbh McGuckian read by Stephen Rea, music played by Neil Martin (West Ocean String Quartet). A version of of Emmet’s Speech from the Dock was also read.

Lost & Found: There is a curious volume of pamphlets - now very rare - by St. John Mason, on Trevor, the prison doctor at Kilmainham, in whose burial place at St. Peter’s Church there was found recently in a prison coffin the headless skeleton of a young man supposed to be Emmet.’ (‘The Collins Collection’ [being a report on the library collection of James Collins], in The Irish Book Lover, June-July 1917, Vol. VIII, Nos. 11-12; p.131.)

[ top ]