|

Aidan Higgins

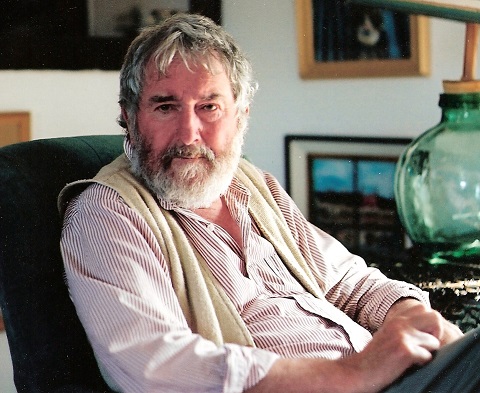

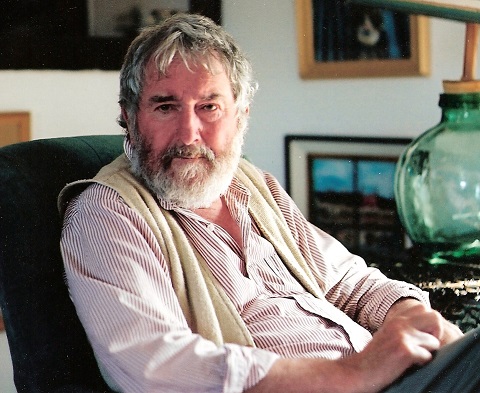

Life

| 1927-2015 [Aidan Charles Higgins]; b. 3 March, Springfield [Hse.], Celbridge, Co. Kildare, to a family which had made money in copper mined in Tombstone, Arizona; ed. elbridge Convent; Killashee Preparatory School, and Clongowes Wood College [SJ]; met Samuel Beckett in London - and threw up out of awe by his own account, 1955; introduced to John Calder by Samuel Beckett, 1956; m. Jill Damaris Anders, London 25 Nov 1955 - with whom three children (Carl, Julien and Elwin - ‘the lads’); travelled in S. Africa as member of marionette team with his wife Anders, 1958-60; worked as copywriter for Dublin advertising firm; Felo de Se (1960), issued by Calder with an epigraph from von Hofmannsthal [‘Wenn die Sonne tief, leben wir mehr in unserem Schatten als in uns selbst’], in which the first story, “Killachter Meadow”, concerns the death of Emily Norton Kervick, one of four unmarriageable Anglo-Irish sisters; contrib. “Sign and Ground” to Evergreen Review (NY May-June 1963), sharing the issue with Samuel Beckett [“Cascando”]; translated in several languages incl. Finnish and Romanian; issued Felo de Se from John Calder (1960), with Beckett’s encouragement - from whom he also received money-gifts; |

| |

| issued Langrishe, Go Down (1966), set in 1932, the year of the Eucharistic Congress, and concerning the three surviving sisters under different names, and especially the love affair of Helen Langrishe with Otto Beck, and later affirmed by Higgins to be an episode of family autobiography [‘my brothers and myself in drag’]; winner of the James Tait Memorial Prize; received the award of the IAL - but sadly called ‘literary shit’ by Beckett, who had previously said, ‘in you together with the beginner we see the old hand’; winner of Berlin Residential Scholarship; Langrishe successfully filmed by BBC TV with Judi Dench and Jeremy Irons playing to script by Harold Pinter, 1978; issued Images of Africa (1971), using epiphanic sections and centred on an unhappy love affair in S. Africa - where he worked in advertising, Johannsberg 1960-61; issued Balcony of Europe (1972), the narrative of Anglo-Irish painter Dan Ruttle’s love-affair with a Charlotte Bayless, an American, in an Andalusian coastal village, and also the final period of his marriage to Olivia [i.e., Jill]; short-listed for the Booker Prize; issued Scenes from a Receding Past (1977), recreating his Sligo childhood up to his marriage; ed. & intro., A Century of Short Stories (1977), for Jonathan Cape; |

| |

| issued Bornholm Night-Ferry (1983), the epistolary narrative of an affair between Finn Fitzgerald (Fitzy), a novelist, and Elin (Marstrander), a Swedish poet; purportedly founded on actual letters to the author; became a founding-member of Aosdána; Irish Academy Award; American-Irish Foundation Award, 1977; Irish Arts Council Grant (1980); also British Arts Council bursaries and the Deutsch. Akademischer Austauschdienst (Berlin); issued Lions of the Grunewald (1993), a novel set around Europe; issued Donkey Years: Memories of a Life as Story Told (1995), and a sequel Dog Days: A Sequel to Donkey Years (1998), followed by The Whole Hog (2000), shortlisted for Irish Non-Fiction Award, Dec. 2001; suffered catastrophic lost of sight after botched operation, c.2002; his autobiographical trilogy was issued in an omnibus edition by John O’Brien’s Dalkey Archive Press as A Bestiary (2004); issued Windy Arbours: Selected Criticism (2005), with Dalkey Archive Press [dir. John O’Brien]; his 80th birthday was marked by a literary symposium at Celbridge, March 2007, and a reissue of Langrishe Go Down by Dalkey Archive; issued Flotsam and Jetsam (1997), versions of fiction; issued As I was Riding Down Duval Boulevard with Pete La Salle (2002), a short piece on his time at University of Texas, ‘adapted from the earplay Boomtown’; |

| |

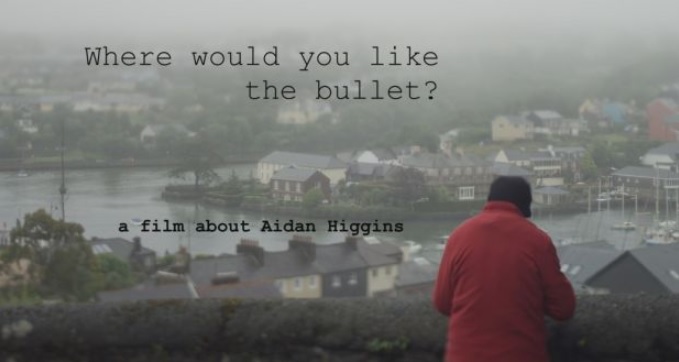

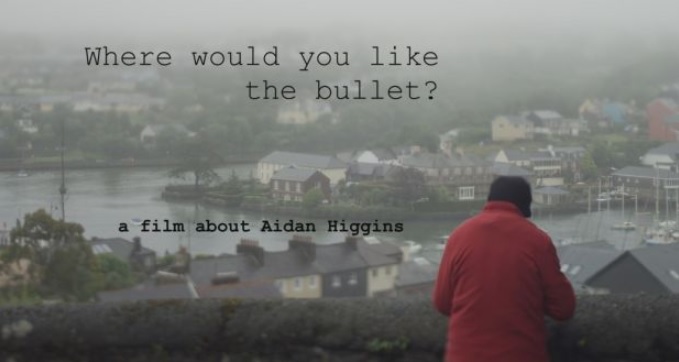

| Balcony of Europe and Darkling Plain [radio plays] were reissued in 2010, together with a Festschrift edited by Neil Murphy; latterly lived in Kinsale; widely regarded as the most talented modern Irish writer not to achieve greatness; Higgins, who invariably trod a fine line between fiction and autobiography, was praised by Samuel Beckett and Claude Simon among others - the latter noting painterly elements of his work; Jeremy agus Judi ar Bhruach Na Siúire, a documentary about the filming of Langrishe, Go Down was broadcast TG4 (Oct. 2014); Higgins met Alannah Hopkin (q.v.) in company with Derek in 1986 when their ages were respectively 59 and 37; lived with together in Kinsale from 1987, together with his children Carl, Julien and Elwin; m. in Dublin, Nov. 1997 [var. 1999]; d. 27 Dec. 2015, in Cramers Court Nursing Home, Ballintobber Lodge; crem. Ringaskiddy; posthum collection March Hares (2017), from Dalkey Archive Press, contains 30 years of essays and introductions; a new documentary, “Where Would You Like the Bullet?”, was screened at the IFT on 3 March 2019. DIW DIL OCIL FDA |

| “I am consumed by memories and they form the life of me.” (Quoted by Brian Lynch in obituary, Irish Independent, 3 Jan. 2016) [available online, or see extract]. |

| Emily Hourican, ‘Novelist Alannah Hopkin: “It was so good when it was good”’ [interview-article] in Irish Independent, 12 June 2017) [see full text - as attached]. |

| Higgins was admired by Annie Proulx for his ferocious and dazzling prose’. (Quoted in Rosita Sweetman, ‘Aidan Higgins: caught on camera in Where Would You Like the Bullet?’, in The Irish Times, 10.05.2019) [see infra]. |

|

|

March 3rd 2019

Sunday morning at 11.am

The IFI Cinema 2, Eustace, Street, Dublin.

A private screening of the 94 min. Film Documentary

on the life and career of Kildare-born writer

Aidan Higgins (1927 - 2015) |

[ Also to be shown at Hugh Lane Gallery, Parnell Sq.,

on 19th May 2019. ] |

|

|

| “Where Would You Like the Bullet?” |

|

| WWYLTB MASTER JANUARY 2019https://vimeo.com/312168891 |

|

| See also ... |

Fund-Raiser organised by

Caroline Smith & Neil Donnelly

at Go Fund - online.

|

|

|

[ top ]

Works

| Fiction |

- Felo de Se (London: John Calder 1960) [“Killachter Meadow”; “Lebensraum”; “Asylum”; “Winter Offensive”; “Tower and Angels”; “Nightfall on Cape Piscator”]; Do., in America as Killachter Meadow (NY: Grove 1961); Do., reissued as Asylum and Other Stories [rev. edn.] (London: Calder & Boyars 1978), 191pp., and Do . (Dallas: Riverrun Press 1978).

- Langrishe, Go Down (London: Calder & Boyars 1966, 1968), 272pp.; Do ., [pbk. rep. edn.] (London: Minerva 1993), 272pp.; Do. (London: Vintage 2000), and Do . (Dublin: New Island Books 2007), 261pp.; Do., in French as Naufrage, trans. by Edith Fournier (Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1968), 372pp.[ltd. edn. of 117].

- Images of Africa: A Diary 1956-60 [Signatures Ser., 11] (London: Calder & Boyars 1971), 71pp.; Do., reissued as Ronda Gorge and Other Precipices: Travel Writing 1956-1989 (London: Secker & Warburg 1989), 229pp.

- Balcony of Europe (London: Calder & Boyars 1972), 463pp. [with 2pp. epigraphs; & 4pp. “Rejected Epigraphs”]; Do. [rev. edn.], ed. Neil Murphy (Dalkey Archive Press 2010).

- Scenes from a Receding Past (London: John Calder 1977), 204pp.; Do . (London: Dalkey Archive Press, 2005), 204pp.

- Bornholm Night Ferry (London: Allison & Busby 1983), 175pp.; Do . [another edn.] (London: Abacus 1985), 175pp.

- Helsingor Station & Other Departures (London: Secker & Warburg 1987), 240pp.

- Weaver’s Women (London: Secker & Warburg 1993), 224pp.

- Lions of the Grunewald (London: Secker & Warburg 1993; London: Minerva 1995), xi, 301pp.

- Flotsam and Jetsam (London: Minerva 1997), 470pp., pb.; Do. [rep. edn.] (Chicago: Dalkey Archive Press 2002), 470pp. [incl. “Berlin After Dark”; “North Salt Holdings” - formerly “Killachter Meadow”; “Asylum”, “Helsingör Station”, “Black September”, et al.].

|

| Translations |

- Naufrage, [Langrishe, go down], traduit [...] par Edith Fournier (Paris: Éditions de Minuit 1968),

372pp. [ltd. edn. 117 copies]

|

| Autobiography |

- Donkey’s Years: Memories of a Life as Story Told [by Aidan Higgins] (London: Secker & Warburg 1995; Minerva 1996), 366pp.

- Dog Days: A Sequel to Donkey Years (London: Secker & Warburg 1998;

Vintage 1999), 286pp.

- The Whole Hog: A Sequel to Donkey’s Years and Dog Days (London: Secker & Warburg 2000), xiv, 400pp. [var. 2001].

- As I was Riding Down Duval Boulevard with Pete La Salle (Kinsale: Anam Press 2002), 25pp. [on his time at Univ. of Texas; adapted from the earplay Boomtown ; ltd. edn. of 400].

- A Bestiary: An Autobiograpy (Dalkey Archive Press 2004), 742pp. [comprising autobiographical volumes of 1995, 1998 & 2000; for contents table, see Amazon Books - online]

|

| Criticism |

- Windy Arbours: Collected Criticism [Irish Literature Ser.] (Normal [Ill.]; London: Dalkey Archive Press 2005), 308pp. [incls. essays on William Faulkner, Djuna Barnes, and Jorge Luis Borges, Ralph Cusack, and Dorothy Nelson].

- March Hares (Columbia UP 2015; rep. Dalkey Archive Press 2017), 286pp. [essays and introductions incl. writings on Melville, Flaubert, Joyce, Beckett - in an essay on John Minahan’s portraits - Flann O’Brien, John McGahern, and Charles Olson.

|

| Miscellaneous |

- “Sign and Ground”, in Evergreen Review, 30 [NY] (May-June 1963), 127pp., ill. [with “Cascando”, by Samuel Beckett]

- Extract from Langrishe Go Down, in Dolmen Miscellany of Irish Writing, eds., J. Montague & T. Kinsella (Dolmen Press 1962), pp.12-26.

- “Sign and Ground” [story], in Evergreen Review, 30 (May-June 1963) [also incls. "Cascando" by Samuel Beckett].

Ed. & intro., A Century of Short Stories (London: Jonathan Cape 1977), 414pp. [also publ. by London : Book Club Associates].

- Ed. & Intro., Carl, Julien & Elwin Higgins, Colossal Congorr & the Turkes of Mars: A Century of Short Stories (London: Jonathan Cape 1979), 96pp., ill. [‘written ... by my three sons at ages varying from five to fifteen, covering a period of perhaps ten years’; ills. by the authors.]

- contrib. ‘Paddy’ [an appreciation], to Frances Ruane, Patrick Collins, with a foreword by James White (Dublin: Arts Council/An Chomairle Ealaion 1982), 118pp.

- ‘Paradiddle and Paradigm’ [review of works by Bernard MacLaverty and John Montague], in Irish Review (Autumn 1988), pp.116-18.

- Introduction to John Minihan, Samuel Beckett (London: Secker & Warburg 1995), 92pp. [photo-tribute]; Do. ([Paris]: Le Petit Libraire] Anatolia 1995), 49pp. [51 ills.].and Do. ([NY: George Braziller 1996), 4, 92pp., ills.

- ‘The Faceless Creator’, in Ireland of the Welcomes: ‘New Irish Writing’ [Special Issue], ed. Derek Mahon (Sept.-Oct. 1996), pp.16-19.

- Blind Man’s Bluff (NY: Columbia UP 2012), 88pp.

|

| Screen plays |

- Harold Pinter, The French Lieutenant’s Woman and Other Screenplays (London: London : Methuen, 1982; Faber & Faber 1991), 277pp. [incls. The French Lieutenant’s Woman of John Fowles; Langrishe, Go Down by Higgins; The Last Tycoon by F. Scott Fitzgerald.]s

|

| Radio drama |

- [For BBC] Assassination in Sarajevo; Imperfect Sympathies; Discords of Good Humour; Vanishing Heroes [BBC entry for Prix Futura, 1885]; Texts for the Air; An Elegy for England; Winter is Coming; Zoo Station, Boomtown, Texas US (1987). For RTÉ1: The Tomb of Dreams.

|

| |

| [ See Hedwig Gorski, “Aidan Higgins Bibliography” - online; accessed 09.01.2016; incls. summaries of major texts.] |

| Reprint series - Normal, Ill.; London: Dalkey Archive Press 2010 - prop. John O’Brien |

- Balcony of Europe [rev. edn.], ed. Neil Murphy (Dalkey Archive Press 2010), 425pp.

- Darkling Plain: Texts for the Air, ed. by Daniel Jernigan (Dalkey Archive Press 2010), 509pp.

- Neil Murphy, ed., Aidan Higgins: The Fragility of Form (Dalkey Archive Press 2010), 300pp. [Festschrift].

|

| Note: A letter to Higgins from Samuel Beckett, dated 17 May 1965, is held in Trinity College as MS10402/222 - see Lois More Overbeck, ‘Letters’, in Samuel Beckett in Context, ed. Anthony Uhlmann (Cambridge UP 2013) [Notes], p.438. |

[ top ]

Criticism

| Studies |

- Neil Murphy, ed., Aidan Higgins: The Fragility of Form [Dalkey Archive Scholarly Ser.] (

Champaign, Ill.; London: Dalkey Archive Press 2010),

358pp.; contribs. by writers Annie Proulx, John Banville, Derek Mahon & Dermot Healy; scholars Keith Hopper, Peter van de Kamp, George O’Brien, and Gerry Dukes.]

- Alannah Hopkin, A Very Strange Man: A Memoir of Aidan Higgins (Dublin: New Island Press 2021),

368pp.

|

- Morris Beja, ‘Felons of Our Selves: The Fiction of Aidan Higgins,’ in Irish University Review, 3, 2 (Autumn 1973), pp.163-78

- John Hall, interview with Higgins in Manchester Guardian (11 Oct. 1971), p.8

- Roger Garfitt, ‘Constants in Contemporary Irish Fiction’, in Douglas Dunn, ed., Two Decades of Irish Writing (Cheadle: Carcanet; Chester Springs: Dufour 1975).

- Robin Skelton, ‘Aidan Higgins and the Total Book’, in Mosaic, 19 (1976), pp.27-37 [rep. as Chap. 13 of Celtic Contraries (NY: Syracuse UP 1990), pp.211-23]

|

Review of Contemporary Fiction, 3, 1. (Spring 1983) |

| William Eastlake & Aidan Higgins Special Number |

- Sam Baneham, ‘Aidan Higgins: A Political Dimension’, in Review of Contemporary Fiction, 3.1 (Spring 1983), pp.168-74.

- [George] O’Brien, ‘Scenes From A Receding Past’, in Review of Contemporary Fiction (Spring 1983), pp.164-166.

- Healy, Dermot. ‘Towards Bornholm Night-Ferry and Texts For the Air: A Rereading of Aidan Higgins’, in Review of Contemporary Fiction, 3.1 (Spring 1983), pp.181-91.

- Robert, Buckeye, ‘Form as the Extension of Content: ‘their existence in my eyes’’ in Review of Contemporary Fiction, 3.1 (1983), pp.192-95.

- Sean Golden, ‘Parsing Love’s Complainte: Aidan Higgins on the Need to Name’, in Review of Contemporary Fiction, 3.1 (Spring 1983), pp.210-20 [typescript available at Academia.edu - online].

- Sean Golden, ‘Parsing Love’s Complainte: Aidan Higgins on the Need to Name’ , in Review of Contemporary Fiction, 3.1 (1983), pp.210-220.

- John O’Brien, ‘Scenes From A Receding Past’ in Review of Contemporary Fiction, 3.1 (Spring 1983), pp.164-66.

|

|

- Rüdiger Imhof & Jürgen Kamm, ‘Coming to Grips with Aidan Higgins’ Killachter Meadow: An Analysis’, in Études Irlandaises (Lillie 1984), pp.145-60 [available online].

- Rüdiger Imhof, ‘Bornholm Night-Ferry and Journal to Stella: Aidan Higgins’s Indebtedness to Jonathan Swift’, in The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, X, 2 (Dec. 1984), pp.5-13.

- Vera Kreilkamp, ‘Reinventing a Form: The Big House in Aidan Higgins’ Langrishe Go Down ’, in The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, 11, 2 (1985), pp.27-38 [rep. in Kreilkamp, The Anglo-Irish Novel and the Big House (NY: Syracuse University Press 1998), pp.234-60].

- Otto Rachbauer, ‘Aidan Higgins, “Killachter medow” und Langrishe Go Down sowie Harold Pinters Fernsenfilm Langrishe, Go Down: Variationen eines Motivs’, in Rauschbauer, ed., A Yearbook of Studies in English and Language and Literature, Vol. 3 (Vienna 1986), pp.135-46.

- Rüdiger Imhof, ‘German Influences on John Banville and Aidan Higgins’, in Wolfgang Zach & Heinz Kosok, eds., Literary Interrelations: Ireland, England and the World, Vol. 2 (Tübingen: Gunter Narr 1987), pp.335-47.

- Klaus Lubbers, ‘“Balcony of Europe”’: The Trend towards Internationalisation in Recent Irish Fiction’, in Zach & Kosok, eds., op. cit. (Tübingen: Gunter Narr 1987), pp.235-47.

- George O’Brien, ‘Goodbye to All That,’ in The Irish Review, 7 (Autumn 1989), pp.89-92.

- Patrick O’Neill, ‘Aidan Higgins’ in Rüdiger Imhof, ed., Contemporary Irish Novelists [Studies in English and Comparative Literature, ed. Michael Kenneally & Wolfgang Zach] (Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag 1990), pp.93-107.

- Neil Murphy, ‘Dreams, Departures, Destinations: A Reassessment of the Work of Aidan Higgins’, in Graph: A Journal of Literature & Ideas (Cork: Summer 1995), pp.64-71.

- Eamonn Wall, ‘Aidan Higgins’s Balcony of Europe: Stephen Dedalus Hits the Road’, in Colby Quarterly(Winter 1995), pp.81-87.

- Neil Murphy, ‘Aidan Higgins’, in The Review of Contemporary Fiction [Dalkey Archive Press, Illinois] (Fall 2003), pp.49-83.

- Neil Murphy, ‘Dreams, Departures, Destinations: A Reassessment of the Work of Aidan Higgins.’, in Graph: A Journal of Literature & Ideas, 1 (1995), pp.64-71.

- George O’Brien, ‘On the Pig’s Back’: Review of The Whole Hog (2000), in The Irish Times (7 Oct. 2000), p.67.

- Neil Murphy, ‘Aidan Higgins,’ in The Review of Contemporary Fiction, 23, 3 (2003), pp.49-83.

- Neil Murphy, ‘Aidan Higgins - The Fragility of Form’, in Irish Fiction and Postmodern Doubt: An Analysis of the Epistemological Crisis in Modern Irish Fiction [Studies in Irish Literature Number, 12] (Edwin Mellen Press 2004), 286pp. [Chap. 2].

- John Banville, review of Langrishe Go Down, A Bestiary, and Flotsam and Jetsam (all published in US by Dalkey Archive), in The New York Review of Books, 51, 19 (2 December 2004) [‘Although Higgins went on to produce further novels [...] Langrishe is without doubt his masterpiece’].

- Kevin O’Farrell, ‘Phenomenological fiction: Aidan Higgins via Edmund Husserl’, in Irish University Review (2013) [available online]

- Kevin O’Farrell, ‘In search of lost selves: Aidan Higgins’ Scenes from a Receding Past’, in Irish Studies Review (Oct. 2013), pp.461-69 [see abstract].

- Brian Lynch, Obituary, Irish Independent (3 Jan. 2016) [see extract]

|

| |

See also Ruth Frehner, The Colonizers’ Daughters: Gender in The Anglo-Irish Big House Novel (Tubingen: Franacke 1999), 256pp.

|

| Reviews & interviews |

- Bruce Arnold, review of Aidan Higgins, Langrishe, Go Down, in Dublin Magazine (Spring 1966) [see extract].

- Gerry Dukes, ‘Recycled living, required reading’, review of Flotsam and Jetsam, in The Irish Times (22 Feb. 1997), with photo-port of Higgins with a young neighbour, by Ted McCarthy [extract].

- C. L. Dallat, review of Flotsam and Jetsam, in Times Lit. Supplement (21 March 1997), p.23.

- Caroline Walsh, interview with Higgins in The Irish Times (15 Oct. 1977), p.12.

- Robert Buckeye, ‘Form as the Extension of Content: “their existence in my eyes”’ [review], in Contemporary Fiction, 3.1 (1983), pp.192-95.

- Rüdiger Imhof, review of Lions of the Grunewald, in Linenhall Review, 10, 3 (Winter 1993) [see extract].

- Neil Murphy, ‘Review of Lions of the Grunewald’, in Irish University Review, 25.1 (Spring/Summer 1995), pp.188-190.

- Dermot Healy, ‘Donkey’s Years: A Review,’ in Asylum Arts Review, 1, 1 (Autumn 1995), pp.45-46 [‘At last Higgins has succeeded in giving himself the fictional life he was always seeking’].

- George O’Brien, ‘Consumed by Memories’ review of Donkey’s Years, in The Irish Times (10 June 1995), Weekend, p.9. [see extract].

- Derek Mahon, ‘An Anatomy of Melancholy’, review of Dog Days, in The Irish Times (7 March 1998), Weekend [p.6-7]].

- George O’Brien, ‘On the Pig’s Back’, review of The Whole Hog, in The Irish Times (7 Oct. 2000), Weekend, [p.6-7].

- Annie Proulx, ‘Drift and Mastery’, review of Flotsam & Jetsam, in The Washington Post (16 June 2002), Sunday [sect., T07].

- Keith Hopper, review of sundry works by Higgins, in Times Literary Supplement (2 April 2010), pp.3-4 [see extract].

- Emily Hourican, ‘Novelist Alannah Hopkin: “It was so good when it was good”’ [interview-article] in Irish Independent, 12 June 2017) [see extract].

- Rosita Sweetman, ’Aidan Higgins: caught on camera in Where Would You Like the Bullet?’, in The Irish Times (10 May 2019) [see extract].

|

Obituaries & memoirs incl. |

- Brian Lynch, Obituary for Aidan Higgins, in Irish Independent (3 Jan. 2016) - as attached.

- Obituary, in The Irish Times (16 Jan. 2016) - available online.

- Rosita Sweetman, ’Aidan Higgins: caught on camera in Where Would You Like the Bullet?’, in The Irish Times (10 May 2019) - see infra.

- Kate Webb, review of Aidan Higgins, Langrishe, Go Down and March Hares, in Times Literary Supplement (31 March 2018), rep. at Nothing is Lost (31.03.2018) - as infra.

|

| See tributes to Aidan Higgins, with contributions by John Banville, Colm Tóibín, Rosita Sweetman, Éilís Ní Dhuibhne, Rob Doyle, George O’Brien and John O’Brien (publisher) - The Irish Times (4 Jan 2016) - online, or as attached. |

[ top ]

Commentary

| Brian Lynch, Obituary, in The Independent [Dublin] 93 Jan. 2016) |

‘Higgins’s relationship with Joyce’s chief disciple, Samuel Beckett, is revealing. Beckett not only persuaded John Calder to publish Felo de Sé, as collection of Higgins’s short stories, in 1956, he also helped the impoverished young writer with gifts of money. And even earlier he gave him advice - it was an unheard-of thing for the future Nobel Prizewinner to do. The advice, which came in handwriting so cramped and spiky Higgins’s mother had to decipher the letter for her son, was typical Beckett: “Despair young and never look back.”’ Lynch ends: ‘Aidan Higgins was a fierce man entirely’ |

| —Available online; accessed 12.01.2016. |

Bruce Arnold, review of Aidan Higgins, Langrishe, Go Down, in Dublin Magazine (Spring 1966), gives a clear account of the framework of the novel and an assessment of its relation to its influences. Arnold ends by characterising it as ‘a fine, distinguished and powerful novel, highly personal in content and form, rich in evocation of the countryside of the Liffey Valley, and containing memorable combination of two characters, lovers, who are approached by the author in quite different ways, each with equal success, so that they meet, or rather collide, and strike fire from one another.’ The lovers are Imogen Langrishe and the German student Otto Beck, who awakens the sexual appetite of the seedy virgin, one of the dotty sisters of the poor-gentile family, an epitome of her country. ‘It is not a perfect book. The style is obstrusive at times [...] occasionally [...] the form outruns the content and the tension is lost. But Langrishe, Go Down is an important book. It is a mature, cosmopolitan, yet very Irish.’ ( p.79).

Gerry Dukes, ‘Recycled living, required reading’, review of Flotsam and Jetsam, in The Irish Times (22 Feb. 1997), pp.‘All his writing life Higgins has worked at the ragged, jagged interface where fiction and autobiogrpahy jostle’; Higgins has produced a “body of work” the coherence of which shifts or is in flux. some of this flux is self-induced in that Higgins has withdaw his big brute of a novel, Balcony of Europe (1972)- shortlisted for the Booker in that year - but a thoroughly reworked and wonderfully crafted segment called “Catchpole” appears in the present volume. Additionally some of his earlier work … is unobtainable except in truncated form in other gatherings’; compares fate of his work with that of Joyce and bekett in awaiting academic sanction; Donkey’s Years ‘redefined the genre of autobiopgrahy but those of McCourt [&c.] command the public attention.’

Rüdiger Imhof, review of Lions of the Grunewald, in Linenhall Review, 10, 3 (Winter 1993), offers adverse judgement noting its confusion and ‘heteroglossia’; includes acknowledgement of the mention of the critic’s own name in the text anent his former enthusiasm for “Killachter Meadow” which Higgins turned into Langrishe, Go Down, and which he characterises again as one of the finest acheivements of Irish fiction in the last couple of decades; refers disparagingly to anacronym for Deutsche-Internationale Literatur-Dienst Organisation - viz., Irish writer Dallan Weaver, of Trinity, arrives in Berlin with wife and son for one-year appointment with DILDO; falls prey to 28 yr-old Lore [...]; priapic fumblings in doorways and ditches; pregnancy and abortion; leaves wife and son for her; travels. Imhof quotes: ‘Ireland, that evergreen land of obelisks and follies, being still very much à la mode, many young people going there to find out another of their illusory “real things”. In each and every pub the Dubliners roar out “Yo[u]re dhhrunkk, youre dhhrunkk!” etc., most lustily’; Higgins resembles Joyce in that he does not know where to stop. Also summarises Balcony, in which Dan Ruttel, an Irish painter, has an inconclusive extra-marital affair with an American woman, Charlotte Bayless, in Andulusia (p.23).

George O’Brien, reviewing The Whole Hog (2000), in The Irish Times (7 Oct. 2000), describes the work as a concluding volume of remarkable autobiographical trilogy; life and loves of Rory Hill, landless, shaugraun, thinly disguised persona; comfortable childhood in Springfield Hse., Celbridge; Clongowes Wood School; tour of Europe with puppet company; journey to S. Africa; meeting with first wife (Coppera, in The Whole Hog); sojourns in Spain; sorties from family home in Muswell Hill [London] to mistresses in Berlin, Denmark; trip to Mexico with second wife; nothing of his visit to University of Texas; ‘all of Higgins’s fiction is revisited’; Mumu, the author’s mother; identifies original of Otto Beck in Langrishe, Go Down; revisits material of Balcony of Europe ‘loses its langour while preserving its passion’: O’Brien); infidelity in Bornholm Night Ferry more complicated than it previously seemed; ‘Higgins never blinks’; ‘It’s too simplistic to think of Rory as the heart and Higgins the head’; ‘The whole story must include an awareness of the telling’; lists, sketches, anecdotes, travelogue, diaries, bits of gossip, historical footnotes, elements of a soap-opera, letters, imaginative reconstructions (Battle of Kinsale as rugby match) …; section entitle “Borges and I”; satirical jabs at Celtic Tiger ‘go off at half-cock’; ‘no spoiled Proust … much too much himself, inimitable and impenitent’.

Keith Hopper, review of sundry works by Aidan Higgins, in Times Literary Supplement (2 April 2010), pp.3-4: ‘Aidan Higgins is often regarded as a “writer’s writer”, which is usually code for contrary, experimental and out-of-print. Derek Mahon, writing in the Times Literary Supplement in 2007, called him “an austere and often difficult writer, more than a touch old-fashioned, with an astringency that can stir the bile of whippersnappers”. Annie Proulx, in a review beloved of blurb writers, marvelled at how “the ferocious and dazzling prose of Aidan Higgins, the pure architecture of his sentences, takes the breath out of you”. And Frank O’Connor - whose own work Higgins rather brutally dismissed as “sentimental jingoism” - simply declared that “Higgins is a born writer, in love with language and what language can do”. / Paradoxically, this love of language -along with Higgins’s restless quest for more complex and revealing narrative forms - has not always found favour with critics, some of whom seem to object to the patterned intricacies of his lush and melancholy prose. Roger Garfitt, for instance, writing in 1975, complained about a certain “heaviness of language” that is “altogether too writerly, too hedged with words”. Moreover, Garfitt argued, “Reality is internalised, transmuted by Higgins’s style into some sort of inner world, so that one could often be uncertain whether he is writing about a real or a dream world”. Whatever it says about the creamy density of Higgins’s style, this does seem a slightly churlish complaint. Are dreams not part of our reality? Is fictionalized reality not a kind of dream? Aidan Higgins certainly thinks so, or as his alter ego Fitzy says in Bornholm Night-Ferry (1983), pp.“As to dream (perhaps the only word we cannot put quotation marks around) and ’reality’, whatever that might be, well they are for me one and the same”.’ (For full text, go to RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

Billy Mills, on Higgins, in The Guardian (26 Aug. 2008) [Fiction Blog]: ‘[...] Higgins is essentially a novelist of memory and its unreliability. His protagonists are generally alienated from each other by shared experiences differently remembered. He admires Beckett and applies Beckettian methods to a fictional world that more nearly resembles the quotidian than the older writer’s does. Crucially, despite their mutual incomprehension his characters are more like real people than Beckett’s and he admits the importance, the almost redemptive quality, of sexual love into his fictional universe. His 1983 novel Bornholm Night-Ferry is the story of two adulterous lovers, Finn Fitzgerald, an Irish novelist, and Elin Marstrander, a Danish poet. The couple’s affair begins in Nerja and their relationship continues through a series of letters and a number of fruitless meetings. Unfortunately, they manage to construct mutually incompatible fictions out of their shared experiences, with inevitable consequences. / Everything that I have said about Higgins' fiction can also be said of his three volumes of memoirs, Donkey’s Years, Dog Days, and The Whole Hog, collected as A Bestiary. The books include family photographs from Higgins' Celbridge childhood and we learn early on that the house he grew up in had previously belonged to a family called Langrishe. The memoirs include retellings of many of the sources of Higgins' fiction. / However, everything in the memoirs is not what it seems. The protagonist’s family members are not actually named, but referred to by pet name. More interesting still is that this protagonist turns out to be someone called Rory of the Hills, yet another Higgins alter ego. In fact, the memoirs are effectively an inverse of the novels; they are fictions disguised as factual accounts. / Boundaries between truth and lies, memoir and fiction simply don't matter. It’s an approach that has not won Higgins a mass readership, and without risk-taking publishers such as Calder [online] and the Dalkey Archive online] his books would never have been published at all. I suppose he can take some consolation in the fact that having fewer readers makes it less likely that he'll be sued by an irate literalist. [End.]’ (Available at The Guardian, 26 Aug. 2008 - online; accessed 20.07.2017.)

| See also Brian Lynch, Obituary for Aidan Higgins, in Irish Independent (3 Jan. 2016) - as attached. |

Kevin O’Farrell, ‘In search of lost selves: Aidan Higgins’ Scenes from a Receding Past’, in Irish Studies Review (Oct. 2013), pp.461-69 - Abstract: ‘This essay makes the case for a fresh evaluation of Aidan Higgins’ long-neglected autobiographical novel Scenes from a Receding Past. It argues that it is most fruitfully understood as a contribution to the phenomenology of personal identity and that many of its formal idiosyncrasies, especially its deviations from the standard formula for Künstlerroman, are a direct result of its preoccupation with general concepts of selfhood rather than a concern with society, or with the artist’s role. I trace the genealogy of Higgins' innovative and unique form of realism in this work, and in the novel to which it forms a prequel, Balcony of Europe, to his attempts to escape the influence of James Joyce; and using the work of, amongst others, Paul Ricoeur, demonstrate how his fiction contributes to a new understanding of the relations between narrative, memory, imagination, and consciousness.’ O’Farrell writes: ‘What makes Higgins’ autobiographical novel of formation so refreshingly different from others is his concern with the human need for self-narrative, rather than simply the artist’s evolution. Scenes, of course, recalls In Search of Lost Time in its depiction of a man striving to re-create his past, the crucial difference, of course, is that, pointedly, Dan never experiences a revelatory moment in which he decides to write his life story. It is this very fact that makes Scenes so unique amongst twentieth-century novels, particularly other self-reflexive works, and is the main source of its power. In this concern with the essential features of consciousness, shared by artists and grocers alike, Higgins shows the continued influence of the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl upon his fiction. His novel seeks to capture reality rather than taking the seemingly radical but ultimately facile route of merely questioning representation.’ [Full text available at Irish Studies Review > Taylor & Francis publishers - online, or as attached].

[ top ]

Rosita Sweetman

| ’Aidan Higgins: caught on camera in Where Would You Like the Bullet?’:

Rosita Sweetman on Neil Donnelly’s documentary about a great if difficult writer (Irish Times, 10 May 2019) |

[...]

Aidan was in with the big shooters from the get go. Samuel Beckett, later a friend, said in praise of Felo de Se, Aidan’s first collection of short stories, “in you together with the beginner we see the old hand”, the Spectator praising his “bitter, poetic intensity”, his Nabokovian writing to achieve “aesthetic bliss”, Frank O’Connor pronouncing him “in love with language, and what language can do”.

Fame arrived early for Higgins with the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for his first novel Langrishe Go Down, where he turned his “brothers into sisters”, situating them in a decaying Springfield, one sister braving a love affair with odious know-it-all lodger Otto Beck (“You are an imbecile”).

Beckett, his hero, famously disliked Langrishe, dubbing it “literary shit”. From then on the books left the relatively calm pastures of “literary novels”, heading into the rough, uncharted and less controllable waters of autobiographical fiction, a genre he perfected. A way, believes Prof Neil Murphy, “of letting the chaos in” so that “everything feels just out of our control, feels ‘fluid’.” Just like life.

The critics were not so happy.

In Balcony of Europe, his sprawling masterpiece following on from Langrishe, Aidan said he wanted to write a book in which “nothing was made up”. The story of a passionate love affair between an Irish artist (Higgins thinly disguised) and the beautiful blonde wife of an American visiting Andalucía where Jill and Higgins now lived with their three sons, Balcony was so not made up it must have been hell for Jill - to live through, and to type up. No! Yup, he had Jill type the manuscript; that she regularly threw typewriter and manuscript out the window is no surprise.

[...]

His much-loved friend of Berlin days, Martin Kluger, believes Aidan showed a certain “flaw of character” in “relishing the enslavement of the erotic”. Hmmm.

“There’s something missing in Irish literature if I may say so,” Aidan believed, “it’s Adam and Eve - they have been forgotten.”

Certainly the next two books after Balcony, Lions of the Grunewald and Bornholm Night Ferry, got their juice from liaisons amoureuses. Lara O Muirithe of Trinity College, a passionate devotee, believes in Lions of the Grunewald Higgins perfected the “omnisensual, omnitextual” techniques begun in Balcony. Bornholm Night Ferry, based on letters between Higgins and another, this time Danish, inamorata - the letters “titivated up” by the author - is a “masterpiece”, believes Neil Murphy; a love affair recalled with, says Prof Keith Hopper of Oxford, a “beautiful Beckettian sense of failure”.

Ironically when Jill finally kicked him out in the late Seventies the liaisons stopped; had they worked only so long as he had safe harbour, Jill and “the lads” to sail home to?

Dog Days, the second of the autobiographical trilogy, written when he was living alone in Wicklow, is described as one of his more accessible books. It’s also the driest. Apart from an astonishing portrait of his younger brother Colman, “the Dote”, and wife Stella, this was Aidan without amor, without wife, without “the lads”, barely Aidan at all.

Then he met Alannah. “I very much liked the way he listened to me,” Alannah says simply. “He took me seriously - this doesn’t often happen particularly with older men of distinguished literary pedigree.” And so the second marriage began. And continued, for many happy years.

More books appeared: The Whole Hog, Flotsam and Jetsam, Windy Arbour, Blind Man’s Bluff, March Hares.

Sadly, the recognition every artist craves stubbornly refused a return appearance. The early fame had cooled to near zero. The Irish reading public whom Beckett once said “couldn’t give a fart in their corduroys about art” looked resolutely the other way. Higgins was a “difficult” writer. No, he was an impossible writer! HE DID NOT REVERE JOHN MC GAHERN. WHAT WAS THE BLOODY MATTER WTH HIM?

There were academics, friends, who remained faithful - Prof Neil Murphy in Singapore, Gerry Dukes in Limerick, Keith Hopper at Oxford, the English literature department at Trinity, the University of Texas at Austin which bought his papers, writers Brian Lynch, John Banville, Adrian Kenny all cared, and still care, as well of course as the uniquely wonderful Dalkey Archive Press with imprints old and new.[...]

|

| Available online; see full-text copy as attached. |

[ top ]

| Kate Webb, review of Aidan Higgins, Langrishe, Go Down and March Hares, in Times Literary Supplement (13 March 2018) - reprint at Nothing is Lost (31.03.2018). |

Aidan Higgins’s debut novel, Langrishe, Go Down (1966), [is] reputedly the greatest Irish novel serious readers may never have heard of. Writing in the Irish Times, Derek Mahon confirmed not just the novel’s reputation, but the author’s, as “fugitive . . . a thing of hearsay among initiates”. Langrishe concerns four sisters (one already dead) marooned outside Dublin in Springfield, one of Ireland’s decaying Big Houses. The novel is set in the 1930s as fascism creeps across Europe; the Langrishe women are creatures living at the edge of the continent and the end of their wits: ignorant, impoverished and condemned to the loneliest of spinsterhoods, which has turned them in on themselves and set them against one another. The two sisters who narrate the novel fret continually about their fall from respectability, wondering how they have arrived at a place so far beyond the pale.

[...]

Part of the problem for Higgins was the way critics placed his novel. Because of its Big House subject, historical references (James Connolly, Éamon De Valera, Constance Markiewicz, etc) and melancholy lyricism, many thought of it primarily in a national context - another brick in the wall of “old Irish miserabilism”, as Eimear McBride described the tradition recently on Radio 4 - as existing, therefore, in a space disconnected from these continental debates about literature and politics. But this is perhaps a category error: Langrishe is not an example of the isolation of Irish culture, but rather a work that critically dissects it. Disputing the novel’s reading by many reviewers, Higgins underscores this point in another piece included in March Hares. In it, he asserts, “on the subject of misunderstandings and cognate matters, may I be here permitted to state categorically that Langrishe, Go Down is not a Big House novel, nor ever was intended as such”.

John Calder, thinking back over some of the writers he championed during his (heroic) career, singled Higgins out as “greatly under appreciated”. “He is a very strange man”, Calder told an interviewer in 2013, “A great writer, though.” No doubt lack of appreciation played its part in that strangeness, leading to some of the bristliness on display in March Hares, where he returns repeatedly to the matter of Ireland’s “deeply conservative reading public”, the fantastic sales of the “sobsisters” (Nuala O’Faolain, Frank McCourt), the ever-present faces of the fashionable literati (Colm Tóibín, Roddy Doyle), his own remaindering (out of print again), and the all-too-brief mentions of his work in anthologies of Irish literature. Yet he is astute enough to understand that, for an artist, there is existential validation in being excluded: “To feel out of place is, to be sure, quite a salubrious state for a writer to find himself in”. No doubt this is why writers at the edge so often become experts in reinvention. Higgins’s own talent for redeployment and recycling - characters reappear, later memoirs replay passages from earlier fictions - is at odds with the complete lack of wherewithal demonstrated by the Langrishe sisters. He has said the women were based on himself and his brothers, who had grown up in the house that Springfield is modelled on: the sisters, he writes, were characters “in drag”. Presumably one of the reasons for changing their sex is that women more plausibly embody the “weakness” and redundancy that he was intent on exposing.

Langrishe contains some of the most poignant and beautiful writing to be found anywhere on the evanescence of time and the cycles of nature. Inlaid against this lyricism, though - as is often the case in studies of lateness - there are moments when people start to regard themselves anthropologically, and odd notes of the parodic edge into view: “Pray sir, did you ever meet a lady who is a sort of specimen of a bygone world?” Carter’s critique of Britain as a country past its sell-by date still manages to find a way forward for her characters: in the new Sixties culture of camp and cut-up, they recycle and sell off busts of Queen Victoria, clown noses and soldiers’ uniforms. But at Springfield, though the Langrishe women, cloistered in their only heated room, are also surrounded by detritus from the past - pictures of sabre-waving soldiers, a “blackamoor” statue, a sarcophagus vase-stand - these symbols remain oppressive because the stay-at-home sisters have no countering point of view, no way of learning how to flount authority or play in the ruins of their history.

The only outside voice in Langrishe comes from a German doctoral student, Otto, who takes up residence in the gatehouse, lives off the land and pays no rent - a situation the sisters, in their “stifling stasis”, are incapable of doing anything about despite a desperate need for funds. With his masterful manner and apparent knowledge of all things, Otto quickly seduces Imogen, the youngest and prettiest of the sisters, the family’s “one hope”. But because of the novel’s a-chronology, the reader knows from the outset that the hope of this affair, begun in the summer of 1933, is doomed: Langrishe opens in the winter in 1937, with the once lovely Imogen now surrounded by stout bottles, her hair and teeth falling out; it closes after two deaths and a funeral in 1939, “squashing” all hope for the Big House inhabitants and, following the Anschluss, for Europe as a whole.

“Mother Eire was never young”, Higgins writes in March Hares, chastizing Joyce for his mythologizing, and in Langrishe she is a brute, an old hag who squashes the lives of the Langrishe girls like insects. The novel ends with Imogen back in the deserted gatehouse, hiding away among “rotting wainscots” and “mildewed walls”, “spiderwebs” and “dead flies”. In another passage from March Hares, entitled “Ancestral Voices”, Higgins says (playfully, camply) of his own upbringing: “In those stagnant times how we fairly trembled before Authority!” His novel Langrishe, Go Down deserves to be more widely known, not only for its extraordinary mournful beauty, but also for its apocalyptic vision of a culture’s squandering and rottenness, for its thoroughgoing dismantling of the Irish house of fiction, and as one of the great works of European anti-authority. [...]

|

| Available at Nothing iS Lost - online; accessed 10.05.2019. |

| Emily Hourican, ‘Novelist Alannah Hopkin: “It was so good when it was good”’ [interview-article] in Irish Independent, 12 June 2017. |

[...]

”He came to visit a friend, I was asked to help to entertain him, and so I did,” Alannah says. “I liked his voice on the phone before I even met him, then I found him very attractive in person, and that was that. We got talking and suddenly we seemed to have many things in common. I liked his gentleness, his hazel eyes - same as mine - his loyalty to his friends and his enigmatic smile.” It was, she says, “a coup de foudre”.

It was, she says, “a bit dramatic. And terrifying. It’s quite scary. It really was like a thunderbolt. I was 36, and I had never considered it a possibility. I had no idea how old Aidan was at the time, and he looked a lot younger, but we just clicked”. Aidan was 59 at the time; “I thought he was pulling my leg when he told me. I thought he meant to say 49, and even that would have been old. But it didn’t seem to matter.”

They moved in together “straight away”, although they wouldn’t marry for 11 years. “After about six months, Aidan started talking about buying a house, and I had to say ’stop, stop, you mean you really want to buy a house with me? Are you sure?’ He said ’Yes of course, why not?’ It was all easy. He was very decisive.”

They would work separately all day - “I got the room with the door that closes, Aidan worked in the big open-plan sitting room with kitchen” - then meet in the evenings. “At half five or six we’d have a drink together, play Scrabble, maybe go out. We didn’t really talk about the working day. He might if it was going really well, and I might if I had a gripe. But we would never read each other’s stuff.”

It was, Alannah says, “so good when it was good”. And for many years, it was good. But then Aidan began to behave in ways that were strange.

”He had vascular dementia, but it went undiagnosed for a long time, because he had other mental health problems. He had a kind of breakdown, a psychotic episode” - this was around 2002, and was, Alannah says, “accelerated by taking steroids for his eye condition, and seemed related to two of his friends committing suicide”.

It wasn’t the first such episode - “he had had one or two before, and they never really got to the bottom of those. They thought he was mildly bi-polar, so this dragged on for years”.

Finally, in his early 80s, Aidan saw a geriatrician and was diagnosed.

”At least we knew then what was going on,” Alannah says, adding “it’s really terrible when the GP has to explain to you that he’s not going to get better, he’s only going to get worse. And it’s so difficult for him, because he can’t understand what’s going on - although I think he knew more than he let on.”

By then, Aidan’s eyesight was failing and he couldn’t read. “He became very reclusive and silent and no longer wanted to see his friends nor go out. [...]

|

| See full-text copy - as attached]. |

| Sue Leonard, review of Alannah Hopkin, A Very Strange Man, in Books Ireland (July 2021): |

[...]

When the couple married in 1999, mainly to regularise legal and financial matters, they were still, essentially, happy together: ‘Aidan made me feel loved, wanted. I believe he felt the same.

This was just the beginning. Aidan became increasingly difficult. He was inconsiderate, boorish, and sometimes rude to his friends, and Alannah bore the brunt of his moods. Had Higgins changed, or was it age and illness making him so crochety?

As Aidan’s physical health deteriorated, so did his mental state. By the time, at 80, he was diagnosed with dementia, Alannah was living with constant pressure, and fear. Having realised she could never leave him, because the real Aidan was somewhere there, buried in the monstrous one, she had to remind herself to show him affection.

‘You are never alone, yet there is no company,’ she wrote. ‘No companionship. Just his self-absorption. Constant monologues, always the voice, talking to himself when I am not in the room, or to the cats who are better listeners than I am’

When Aidan moved to a care home, Alannah relished the independence that living alone brings. But she was a constant presence at Balintobber Lodge, reading to Aidan, striving, always, to keep the spark of his literary genius alive, right up until he died, in December 2015. |

[ top ]

Quotations

Big-house paupers: ‘We are paupers like the rest of you, except we live in a big house and enjoy credit. But we can’t pay our bills any more. There’s nothing to eat in the place except a few maggoty snipe hanging up in the larder. For all the eating we do, we might just as well not eat at all [...] I have no life in me.’ (Langrishe Go Down, 1966, p.61; quoted in Patrick Rafroidi, ‘A Question of Inheritance: The Anglo-Irish Tradition’, in The Irish Novel in Our Time, ed. Rafroidi & Maurice Harmon, Université de Lille 1975-76, p.12.)

Jesuit bark: In Balcony of Europe (1972), Dan Ruttle speaks of ‘the Jesuit fiction of the world’s order and essential goodness.’ (p.43.)

Mainly about: reviewing Gavin Lambert, Mainly about Lindsay Anderson: A Memoir (Faber), in The Irish Times (24 June 2000), Higgins writes: ‘this sloppily written memoir […] does give some limited insight into the reclusive movie man of Maida Vale who harboured forbidden homo-erotic longings in his breast, longings regulated [sic for relegated ] to the back-burner, kept out of sight. […] We shan’t see his like again.’

| Balcony of Europe (1972) |

| Charlotte’s way of bathing the child touched me, as did her manner of doing a number of mundane things. A long braid of fair hair hung down her back, her beautiful, valorous womanly back, Juno’s love-back and mesial grove. Her skin had a glow from walking on the beach. I watched her moving there, soaping the child. We localize in the body of another all the potentialities of that other life, until it becomes dearer to us than our own. So many ways, so many places, so many seldom different degrees of giving and taking. I’d known exhaltation with her, misery too, a depression of spirit new to me; she half giving and I half taking. I had found, and was already in the process of losing, all that I’d ever wanted, as one unpropitious day followed another, then weeks, and the circumstances that I had no control over not yielding. Je ne sais quoi. |

—Balcony of Europe (1972), p.216; posted by Philip Casey on Facebook following Higgins’s death [31.12.2016] |

‘RTÉ Stills’, review of John Quinn, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Girl [transcript of nine interviews] (Methuen 1987); Maeve Binchy (‘affable … It is not Maeve’s way to lie stretched on the rack’), pp.‘I love Dalkey’; ed. ‘lovely little nursery school’ in Dun Laoghaire; the others are Clare Boylan; Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin, Polly Devlin, Joan Lingard, Dervla Murphy [so excited by Anew McMaster’s Hamlet at Lismore that she cycled round the countryside most of the night recovering]; and Edna O’Brien. Also reviews Bill Naugton, On the Pig’s Back (OUP), Lancashire authobiography. The review is printed with a comic self-portrait [cartoon] by Higgins as a somewhat Joycean mustachio’d gunslinger firing off. (Books Ireland, May 1987, p.85.)

[ top ]

References

Aosdána Gazette lists [additional to above] Ronda Gorge & Other Precipices, travel (due 1987); short stories, Helsingør Station & Other Departures (London: Secker & Warburg 1987); ed. collections, Colossal Congorr & the Turkes of Mars; A Century of Short Stories. Radio drama, Assassination in Sarajevo; Imperfect sympathies; Discords of good Humour; Vanishing Heroes (1985) [BBC entry for Prix Futura]; Texts for the Air; An Elegy for England; Winter is Coming; Zoo Station (all BBC 3 broadcasts); also, due 1987, Boomtown, Texas US. For RTE 1, The Tomb of Dreams).

Bernard Share, ed., Far Green Fields, 1500 Years of Irish Travel Writing (Belfast: Blackstaff 1992), selects prose.

Peter Fallon & Seán Golden, eds., Soft Day, A Miscellany Of Contemporary Irish Writing (Dublin: Wolfhound 1980; Notre Dame UP 1979), gives extracts, “Letters from Bornholm”; “Knepp at the Third River”.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3 selects Scenes from a Receding Past, ‘The Institution’ [994-97]; BIOG 1133 [as supra].

Library catalogues

COPAC: Bornholm Night Ferry (1983, 1985) is erroneously identified in COPAC as a biographical study of Chopin [‘His decline and death, following a series of catastrophes and on the brink of a new style, were final chapters in an often tragic life, but also reflected larger historical forces [...] an intimate close-up of the composer’s last years [...] grappl[ing] with nothing less than a new musical form.’

[ top ] Notes

Sam & Flann: Higgins cites Samuel Beckett’s Murphy and Flann O’Brien’s At Swim Two Birds as early ‘great discoveries in my own literature’ (quoted in John B. Harrington, The Irish Beckett, p.105.)

Anthony Cronin refers to the occasion when Higgins appeared on RTÉ with others and remained completely silent throughout the interview-discussion (in No Laughing Matter, 1988). The same episode is memorialised by Higgins in ‘The Faceless Creator’, in Ireland of the Welcomes, ‘New Irish Writing’ [special issue] ed. Derek Mahon (Sept.-Oct. 1996), pp.16-19, recording that Flann O’Brien was drunk and Benedict Kiely ‘well-oiled’; that Ronnie Drew played on the guitar and sang about ‘the rattle of the Thompson gun’ - ‘may God forgive him’; not having uttered a single word, Higgins is the target of a question, ‘How had it gone?’, from O’Brien. When he praised At Swim in McDaid’s afterwards, O’Brien snarled, ‘You should know better [...] and you a Christian Brothers boy’.

Derek Mahon: Higgins was the dedicatee of “Tractatus”, a poem by Derek Mahon, in The Hunt by Night (London: OUP 1982), also Selected Poems (1991), p.135.

[ top ]

|