| Life | ||||||

| 1713-71 [pseud. “A.F.” for “A Freeman”; also “Civis” and “Citizen” in the Irish Freeman]; b. 16 Sept., at Corofin, Co. Clare; son of Benjamin Lucas, himself the grand-son of Lieutenant-Colonel Benjamin Lucas, a Cromwellian officer, and Mary [née] Blood - a relation of Col. Thomas Blood; wrote an early work on the Kilcorney Cave of the Burren; bapt. Anglican but sometime called a ‘dissenter’ in political affrays against the oligarchy; he became an apothecary [chemist] in Dublin, 1730, and later qualified as an MD (grad. Leyden), sustaining a profitable practice in Dublin afterwards; he issued Pharmacomastix (1741) a part-satirical pamphlet on fraudulent pharmicist-physicians; elected to Dublin Corporation, 1741, and engaged in suit against Alderman oligarchy at the King’s Bench, 1744; | ||||||

| ed. of Citizen’s Journal, 1747, denouncing English restrictions on Irish trade; issued num. pamphlets against oligarchy in Ireland, and especially the vested Aldermen, usually printed by James Esdall of Cork Hill; issued the anti-Catholic Barber’s Letters [1749]; a freq. contributor to Freeman’s Journal, and sometimes called its founder though in fact established by William Le Fanu in 1763; declared a ‘enemy to his country’ [var. public enemy] and imprisoned by the govt. for ‘riotous behaviour’ in his opposition to it at the by-election of 1748; escaped and removed himself to London to avoid trial, 10th Oct. 1749; issued Political Constitutions of Great Britain and Ireland, 2 vols. (1751), denouncing British misrule in Ireland; | ||||||

| visited continental spas and developed a knowledge of hydrotherapy; qualified as a doctor in Leyden (20 Dec. 1752), with a dissertation on gangrene; back in England, he issued An Essay on Waters (1759), a ‘hydrologia physico-chemica’ ded. to His Royal Highness the Prince, with a preface defending himself against hostile physicians especially in Bath (‘I do not, in fact, decry Bath waters; but show their powers in a different light’, p.xix); sought and received a nolle prosequi from George III and returned to Dublin, March 1761 - to great popular rejoicing; successfully urged laws for the control of medicines [drugs, pharmaceuticals] by chemists; contrib. the Irish Freeman, fnd. 1963 and ed. by Henry Brooke [q.v]; | ||||||

| Lucas took a seat in the 1st Irish Parliament of George III; introduced heads of a bill for the better regulation of several trades in the House of Commons, 3 Nov. 1767, resulting in opposition from the Catholic guilds; instrumental in securing the Octennial Act, 1768; said to be responsible for the slur that William Molyneux’s The Case of Ireland’s being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated (1698) was burnt by the common hangman; issued The Rights and Privileges of Parliaments (1770), his last work; d. 4 Nov. 1771, at his home in Henry St.; there is a life-size marble statue of “Dr. Lucas” by Edward Smyth (1772) in City Hall, Cork Hill, Dublin and much unreliable information about the subject, arising from confusions created by his enemies and himself. RR ODNB DIB DIW FDA OCIL |

||||||

|

[ The Wikipedia article on Lucas gives a copious account of his charge that the Aldermen of Dublin had usurped the power of the Corporation - being the commoners and citizens of the City - his subsequent anathemisation as “pubic enemy” by the House of Commons, the Judiciary and the Viceroy resulting in his flight to the Isle and Man and onwards to London and France, together with the prosecution of the printers involved in the publication of his pamphlets. In the course of the controversy, he expressed support for William Molyneux’s [q.v.] argument for the independence of the Irish legistature (House of Commons and the limitation of English power in Ireland which he charged with responsibility for instigating every rebellion in the country. See “Charles Lucas” in Wikipedia - online.]

[ The authoritative entry in the Dictionary of Irish Biography (RIA 2009) - online - is by James Kelly. Both accessed 27.09.2023. See also Sean Murphy, ‘Charles Lucas: A Forgotten Patriot?’, in History Ireland, 3:2 (Autumn 1984) - online - an ample account of Lucas’s role in the formation of Irish Nationalism and the kind and degree of his animosity to Catholics - ]

[ top ]

Works| Pamphlets |

|

|

| Monograph |

|

| Collected Works |

|

| Medical |

|

| Swiftiana |

|

See also Paul Hiffernan (M.D.), ed., The Tickler, Nos. I-VII. The Second Edition, Review’d, Corrected, and Augmented, with Notes humorous and serious; and an Epistle dedicatory to Ch[a]r[le]s L[u]c[a]s, Freeman. (Dublin 1748) [RIA Library].

[ top ]

Criticism| Studies of Lucas by Sean Murphy |

|

|

[ See “Charles Lucas 300” - a website created by Sean Murphy - online. ]

[ top ]

Commentary

Samuel Johnson, “Jonathan Swift”: ‘He had long been hardily singular in condemning this great man’s conduct, amidst the admiring multitude; nor ever could have thought of making an interest in a man, whose principles and manners he could, by no rule or reason honour [or] approve, however he might have admired his parts or wit.’ (Lives of the English Poets, ed. G. B. Hill, OUP 1905, III, 27; quoted in Rosine Aubertine, MA Dip., UUC, 1996; but see further quotations from Johnson, in William J. Maguire, Irish Literary Figures, infra).

Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies, Vol.II [of 2] (London & Dublin 1821) |

|

This firm and incorruptible patriot was born, according to the most probable account, in the city of Dublin, on 26th of September, 1713. Other accounts state him to have been a native of Ballymageddy, in the county of Clare, where his ancestors were substantial farmery. His father, having lost the family property by mismanagement, settled in Dublin, and the first certain notice we can obtain of the son is, that he kept an apothecary’s shop {382 }vat the comer of Charies-street. He afterwards took out a degree in medicine, and (what is not a little singular, considering the virulence with which his character, both public and private, was afterwards attacked) his professional skill was never called in question. Dr. Lucas became early distinguished as a political writer, and, ra consequence of the bold freedom of his opinions, he found it advisable to withdraw to the continent. On his return to Dublin, he became a member of the common council, in which station he determined to exert himself in behalf of the privileges of that body. The new rules, framed in the reign of Charles the Second, by authority from a clause in the act of explanation, had, as in other corporate towns, changed the powers of the city corporation. To increase the influence of the crown, among other innovations, they deprived the Commons of the power of choosing the city magistrates, and placed it in the board of aldermen,subject in its exercise, on each election, to the approbation of the chief governor and privy council. Of this injury Lucas loudly complained; but the law being absolute, could not be combated. Suspecting, however, that in other respects encroachments had been made on the rights of the citizens not justified by law, he examined the city charters, and searched diligently into the ancient records, by which he became convinced that his apprehensions were well founded. He published his discoveries, explained the evidence making from them, and encouraged the people to take the proper steps for obtaining redress. In consequence, a warm contest commenced between the Commons and aidermen in 1741, which continued the two succeeding years. Though the former struggled in vain to recover their lost privileges, the exertions of Lucas in every stage of the dispute, were strenuous and persevering. These services raised him so high in the esteem and confidence of his fellow-citizens, that, on the death of Sir James Somerville, they encouraged him to declare himself a candidate to represent them in parliament. Ambitious of an office so {383} flattering, which would give him the opportunity of exerting his abilities to the greatest advantage, in the service, not only of the city of Dublin, but of his country, he complied with their desire. The election was now no longer a contest between two rival candidates. It became a trial of strength, upon popular principles of civil liberty, between the patriots and government, and kept the Protestants of Ireland in a flame of civil discord for several years. [...] [...] “You know,” said he, “I am no flatterer: you know {366} how often, and in what terms, I have testified my disinterested love and loyalty to his majesty, and my zealous and inviolable attachment to his royal house; that I have always looked upon him as not only politically but actually free from blemish or imperfection; that I know his heart overflows with pure love and benevolence for all his subjects, and that I have myself sensibly shared his royal clemency, in rescuing me from the oppressive hand of that detestable hoary tyrant, a long parliament, with a wicked ministry, and certain iniquitous rulers of this city. His royal touch healed the wounds and bruises given my country through my sides. You know my words, my writings, the tenor of my whole life and conduct, proclaim my invariable gratitude, affection, and duty. And when I forget the deliverer of my country, let my right hand forget its function, and my tongue cleave to the roof -of my mouth. In his royal goodness I repose the most boundless confidence?9 His unreinitied and faithful attention to his parliamentary duties, with the discouraging prospect of failing in every exertion, at length forced from him a confession that he was weary of his task, because he laboured incessantly in vain. “I have," ’said he, in an address to his constituents, “quitted a comfortable settlement in a free country, to embark in your service. I have attended constantly, closely, strictly to my duty. I have broke my health, impaired my fortune, hurt my family, and lost an object dearer to me than life, by engaging with unwearied care and painful assiduity, in this painful, perilous, thankless service. All this might be tolerable, if I could find myself useful to you or my country. But the only benefit that I can see, results to those, whom I cannot look upon as friends to my country, bands of placemen and pensioners, whose merit is enhanced, and whose number has been generally increased in proportion to the opposition given to the measures of ministers. I dare not neglect, much less desert my elation, but I wish by any lawful or honourable means for my dismissal." [...] |

| pp.281-87; see full-text copy in RICORSO > Library > Criticism > History [...] - via index or as attached. |

R. F. Foster, Modern Ireland (1988), p. 238: Foster, Modern Ireland, p. 239, ‘Lucas’s early career ... had in essence been made by the press; he founded the Freeman’s Journal with Henry Brooke in 1763, though it was bought back by the administration for a secret service pension of £50 in 1786. The Castle itself backed papers against Lucas in the 1740s; also remarks on his tracts on municipal reform; riotous behaviour during his candidacy for parliament, 1748, led to his imprisonment, [whence he] escaped to London.

William J. Maguire, Irish Literary Figures (1945), Apothecary in Charles St., Dublin; later MD and Fellow of Royal College of Surgeons, London; lucrative Dublin practice; His Pharmacomastix (A Scheme to prevent Frauds and Abuses in Pharmacy), arose at the expiry of the act requiring examination of pharmacies by law. It includes a satirical portrait, ‘Assuming a pedantic air, one of these gentlemen examines a tongue, and feels the pulse of the patient with great solemnity; then, in a long-spun jargon of technical phrases, - enough to raise the admiration of half the nurses in Christendom - he asks a set of unintelligible questions .. the wily quack, with weightily revolving humph - I thought so - I apprend - armed with fatal pen and ink, prescribes some pernicious burning spirit, which he calls Alexipharmic, not knowing that he is signing the sufferer’s death-warrant ...’ glowed with the same patriotism as Swift, though not the same power of communicating it. Left Ireland to avoid trial, 10th Oct. 1749. Samuel Johnson wrote of him, ‘The Irish Ministers drove him from his country by a Proclamation in which they charged him with crimes which they never intended to be called to prove, and oppressed him by methods equally irresistible by guilt and innocence. Let the man who is driven thus into exile for having been the friend of his country be received in every other place as a confessor of liberty, and let the tools of power be taught in turn that they may rob but cannot impoverish.’ In Addess to the Citizens of Dublin (1778), Lucas wrote, ‘Where there is one honest soul who thirsts for liberty, let it be my task to lead him, till he finds a better guide, through crowds of dignified slaves in gilded fetters, to the fountains of truth and liberty.’ The Public Register; or The Freeman’s Journal, est. by him, Sat. 10 Sept. 1763. Madden gives the dates of his various Addresses to the Freeholders of Dublin, and other publications, as ranging between 1741-1749, and from 1761-1771. There is a description of him in Hardy’s Life of Charlemont, ‘His bodily infirmities, his gravity, his uncommon neatness of dress, his grey and venerable locks, blending with a pale but interesting countenance, in which an air of beauty was still visible, altogether excited attention, and no stranger ever entered the House of Commons without asking whom he was.’ His epitaph at St. Michan’s reads, ‘Lucas, Hibernia’s friend, her joy and pride; / Her powerful bulwark and her faithful guide; / Firm in her Senate, steady to his trust, / Unmoved by fear and obstinately just.’ p.30ff.

Maureen Wall, Catholic Ireland in the 18th c., ed. Gerard O’Brien (1989, On 3 Nov. 1767, Dr Charles Lucas introduced in the Commons [68] heads of a bill for the better regulation of several trades. The non-freeman presented a long petition against it on 20 Feb. 1768, humbly hoping that while trade was under restraints from abroad, nothing would be established in favour of private societies checking the free exercise at home. If as it seemed these ‘pretended privileges’ of the guilds were condemned by common law, they hoped that they would not receive the sanction of any express[ion] now. The heads passed through the lower house, however. [68] Dr. Lucas writes to the guild of merchants congratulating them, saying that non-freemen will now be put ‘in some sort upon a level with freemen who purchase their freedom and [b]ear the burden of public office.’ The heads were rejected in the privy council where the Catholics employed lawyers to present their case, according to Matthew O’Conor [History of the Irish Catholics]. During the discussions of this bill, the Freeman’s Journal (15 Feb. 1774) printed a virulent attack on the Catholic Committee, alleging that papists were formed into clubs and societies, that they had bribed the house of lords and the privy council, &c., in order to break up all united protestant bodies. [71]

Stanley Ayling, Edmund Burke (1988), Lucas controversy, 1748-49 spilled over into patriot and courtier politics on question of Ireland’s dependence on Britain subject to a statute of George II; Lucas pamphlet (unnamed); Burke wrote several anonymous pamphlets, often eloquent, abounding in classical reference, but so carefully and weightily judicious that Burke scholars have failed to agree whether he was basically supportive of Lucas or contemptuous of him .. much likelier the latter [as] borne out by a comment [on his] ‘hackneyed pretences’ and ‘contemptible talents’ in a letter of 12 years after, by which time he evidently regarded him medically as a mountebank also [9]; see also under Burke, supra.

Christopher J. Wheatley, ‘“Our own good, plain, old Irish English”: Charles Macklin Cathal McLaughlin) and Protestant Convert Accommodations’, in Bullán: An Irish Studies Journal, 4, 1 (Autumn 1998), pp.81-102, quotes from Sixteenth Address to the Free Citizens and Freeholders of the City of Dublin (1748); Apology for the Civil rights and Liberties of the Commons and Citzens of Dublin (1748-49), &c. - as infra.

Sean

Sean Murphy, ‘Charles Lucas: A Forgotten Patriot?’, in History Ireland, 3:2 (Autumn 1984) - extract:—

Fabricated letter [sect.] It is also significant that Charles O’Conor of Belanagare, the leading Catholic spokesman and writer against the penal laws, was sufficiently interested in the Dublin election controversy to issue a pamphlet in Lucas’s defence in 1749. Unfortunately, the fact of this support has been overshadowed by a letter fabricated by O’Conor’s grandson and biographer, Revd. Charles O’Conor, which has the elder O’Conor state that he was ‘by no means interested, nor is any of our unfortunate people, in this affair of Lucas’, for whom he allegedly felt ‘some disgust’. This blatant forgery coloured the hostile attitude towards Lucas of nineteenthcentury historians such as Plowden and Lecky, and remains to influence the unwary today due to its inclusion in the most recent (1988) edition of O’Conor’s correspondence. A further indication that those with pro-Catholic sympathies were inclined to support Lucas in 1749 were five articles in the Censor, which are almost certainly the work of the young Edmund Burke. The articles, some of which were signed with the letter ‘8.’, a signature used by Burke in his own journal, the Reformer, exhibit a lofty tone and support Lucas in a relatively cautious and moderate way. ‘8.’ counselled that if ‘penal laws’ had been made for ‘turbulent and seditious times’, the wise judge would suffer them ‘to be forgot in happier days and under a prudent administration’. These Censor articles were first identified as Burke’s in 1923 by the Samuelses, but in 1953 an article by Vincitorio blasted Lucas as a bigoted demagogue whom Burke could never have supported. This article has tended to discourage closer examination of the attribution, and indeed Conor Cruise O’Brien’s recent biography of Burke, The Great Melody, makes no mention at all of Lucas. Nevertheless the evidence for Burke’s authorship of the Censor articles is compelling. As the election paper war raged in the summer and autumn of 1749, the controversy surrounding Lucas’s candidacy was coming to a head. Following pointed comments by the lord lieutenant, the Earl of Harrington, in his opening speech to parliament on 10 October 1749, the house of commons mounted an investigation into Lucas’s election writings and summoned him for questioning. Even as the house deliberated on his case, in the Censor of 14 October a defiant Lucas courageously but unwisely quoted from a work by James Anderson DD, which claimed that Ireland was a distinct kingdom, that Catholics had believed they were taking arms in their own defence in the rebellion of 1641, and that both sides had been guilty of atrocities in the ensuing war. Belief in Catholic guilt in the 1641 rebellion was an article of faith among moderate as well as extreme Protestants, and Lucas’s stance on 1641 and Irish rebellions alone must surely acquit him of the charge of consistent anti-Catholic bigotry. [...]

—Available online; accessed 30.09.2023.

[ top ]

| Essay on Waters (1756) |

|

- Dedicatory letter to His Royal Highness

|

|

|

|

§

|

| Preface |

|

|

Available at Google Books - online.

|

Sundry pamphlets

| ‘There are none so dangerous, as those, who, in Publick, are Protestants by profession, in Private, Papists, in Policy and Practice. Those, who from Conscience, profess the Popish Religion, openly and honestly, deserve our tenderness and Pity, and are much less dangerous to the establishment.’ (A Sixteenth Address to the Free Citizens and Freeholders of the City of Dublin, 1748, pp.31-32; Wheatley, op. cit., p.85); |

[Further:] ‘Lastly, consider to what End have our Ancestors, brave free-born Britons, left their native Climate, to settle in this remote, and then uncultivated Isle? Was it not at the request of an oppressed King, and injured people, to restore their Rights and Liberties, and ot impart a free and generous Spirit to the Whole?’ (An Apology for the Civil rights and Liberties of the Commons and Citzens of Dublin, 1748-9, p.5; Wheatley, p.86.) |

| ‘The Irish, in general, were absolutely treated worse [by the Vikings], than the Victims of themost Savage barbarians; as bad, as the Spaniards used the Mexicans;, or, as inhumanely, as the English, now, treat their Slaves, in America’ [Idem.] |

‘No wonder they should have become implacable Enemies to their lawless, inhuman, perfidious, their worse, than Savage Oppressors: when we find the deluded Wretches, always treated, worse, than a good man could treat Brutes!’ (An Eleventh Address to the Free Citizens [… &c.], [q.d.], pp.8, 11; Wheatley [idem]); |

The foregoing all given, along with further quotations, in Christopher J. Wheatley, ‘“Our own good, plain, old Irish English”: Charles Macklin Cathal McLaughlin) and Protestant Convert Accommodations’, in Bullán: An Irish Studies Journal, 4, 1 (Autumn 1998), pp.81-102. |

[ top ]

Pentarchy: Great Charter of the Liberties of Dublin Transcribed and Translated into English with Explanatory Notes addressed to His Majesty and Presented to His Lords Justice of Ireland by Charles Lucas, a Free Citizen (Esdall 1749) commences with a Dedication in the form of a political history of Ireland which includes remarks on the original Gaelic kingships and the English crown of Ireland: ;As England had formerly been divided into a Heptarchy, so had Ireland, into a Pentarchy; in which State it continued, till it became a Monarchy, under the King of England, about the year 1172. (Ftn. cites G. Cambrensis, M. Paris, J. Brampton, R. Hovenden, Sir. J. Davies. (p.x.) [Available in Collected Political Works at Google Books - online [p.36.]

[ top ]

References

Dictionary of National Biography cites Pharmacomastix (1741); Divelina Libera, an Apology for the Civil Rights and Liberties of the Commons and Citizens of Dublin (1744); behaved during his candidacy for parliament in such a way as to be denounced and threatened with imprisonment, 1748; escaped to London and the continent; Essay on Waters (1756); MP Dublin 1761-71; contrib. Freeman’s Journal from 1763; ‘the Wilkes of Ireland’ [ODNB article by R.D.] A son, Henry Lucas (fl..1795), ed. TCD, MA 1762, wrote occasional verse. See also Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies (1821), Vol. II,, p.381-87.

Esther K. Sheldon, Thomas Sheridan of Smock Alley (Princeton UP 1967), lists A Letter to the Free Citizens of Dublin. By a Freeman, Barber and Citizen (Dublin Feb 12th 1746/7 [B.M.L]; A Second Letter .. By A. F. Barber and Citizen. March 3 1746/7, 16pp. [R.I.A.]; A Third Letter ... Dublin 1747, 22pp. [R.I.A.].

Henry Boylan, A Dictionary of Irish Biography [rev. edn.] (Gill & Macmillan 1988), b. prob. Ballingaddy, Co. Clare; apothecary, Dublin; published pamphlet on abuse of drugs, 1735; campaigned against municipal corruption as councillor with La Touche [?Peter, or same as William George Digges La Touche, 1747-1803, partner in La Touche Bank, Dublin, or brother?]. Advocated independence of Ireland, and fled prosecution to continent, 1749; grad. medicine at Leiden, 1752; elected MP for Dublin, 1761; freq. contrib. Freeman’s Journal, fnd. 1763; pol. pamphlets published as The Great Charter of the City of Dublin (1749). Statue at City hall. d. Henry St.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 1, calls him a regular contributor the Freeman’s Journal, and cites Sean Murphy, ‘The Lucas Affair, A Study of Municipal and Electoral Politics in Dublin 1742-49’ (UCD MA thesis, 1981).

British Library, Proceedings of Lord Mayor and Aldermen in a petition for salary of £500 to Dr. Lucas. [BML 1956 Cat.: Ireland].

Belfast Central Public Library holds Appeal to the commons and citizens of London (1756); also, Lucas’s Papers (1748);

Linen Hall Library, Belfast, holds 1) Addresses (1-20) to the free-citizens and free-holders of Dublin, 1748-9; 2) Appeal to the Commons and Citizens of London, 1756; 3) Divilina Libera, an apology for the rights and liberties of the Commons and Citizens of Dublin, 1744; 4) Magna Carta Liberalum Civitatis Dublini, translated with notes by C. L., 1749. Also The Horse and the Monkey, a fable, humbly ascribed to Mr. C. L.

[ top ]

Notes

Edmund Burke: The young Edmund Burke, while at Trinity College, called Charles Lucas, ‘a demagogue apothecary’ who exhibited a ‘a noxious and insidious tendency“ in writing a number of daring papers against government, and acquired as great popularity as Wilkes did afterwards in London. See Peter Burke, Life of Burke (1853), quoted in Charles Wentworth Dilke, The Papers of a Critic, Vol. 2 (1875; facs. 2023), pp.81-82 - being a review of Peter Burke, The Domestic Life of Edmund Burke (1853), in Athenaeum (10 Dec. 1853, p.323.) Note that Dilke reveals the sentences in Peter Burke’s Life (1853) to be a strong echo of those in Charles McCormack’s Memoir of Burke (1798). [Available at Google Books - online; accessed 20.01.2024.]

H. A. Froude, in Two Chiefs of Dunboy (1899), cites Lucas in connection with his paper, Citizen’s Advertiser (sic), in

Anti-riots: Lucas played a part in quelling the Smock Alley riots of 1754 [var. 1747] as described in Sir John Gilbert, History of Dublin; ‘In the course of the Kelly Riot [1747], Dr. Lucas rises and asserts the rights of the audience, proposing to settle the matter by the wishes of the majority, and ‘called upon those who were for preserving the decency and freedom of the stage to hold up their hands.’ (Gilbert, Vol. II, p.84.)

A Freeman: as a pamphleteer, he used the pseudonymous initials “A. F.”’ and also the full name, “A Freeman”. His pamphlets in connection with Dublin theatre are listed in Sheldon’s bibliography (Thomas Sheridan, 1967), p. 479.

Proto-nationalist? See exchange of letters between Sean Murphy and Sean Connolly in History Ireland (Winter 1995) arising from an article by the former referring to Lucas as ‘an Irish nationalist’ and a riposte in a review of another work by the latter in History Ireland (Autumn 1995). Seemingly Connolly has uncritically cited a forged letter, fathered on Charles O’Conor of Belanagare, in which Lucas is made out to be a Corporation politician and anti-Catholic bigot (p.10).

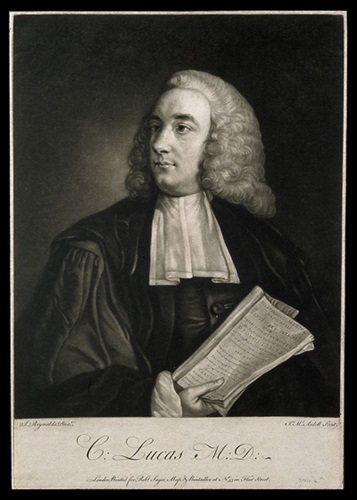

Portrait: there is a full-length statue by Edward Smyth in the City Hall [formerly Royal Exchange], Cork Hill, Dublin, from 1722. See ‘Edward Smyth, Dublin’s Sculptor, in Irish Arts Review, [Yearbook] (1989-90), p.72; also photo. ill., in Brian de Breffny, ed., Ireland: A Cultural Encyclopaedia (London: Thames & Hudson 1982), p.226.

Namesake (1): Sir Charles Lucas (1613-1648), was a royalist officer in the Civil War; with Sir George Lisle, he was shot to death [i.e., executed] by appointment of the Army [i.e., the Commonwealth] after their surrender at Colchester in 1648 - thus becoming objects of many contemp. elegies and celebrations of their loyalty to the Crown.

Namesake (2): Sir Charles Charles Prestwood Lucas (1853-1931) is an author on war in the British Empire (e.g., The Empire and the Anvil, 1916, The Partition and Colonization of Africa, 1922,and The Story of the Empire, 1924).

Freeman’s Journal: Lucas’s reputed founding of the Freeman’s Journal was dismissed by R. R. Madden in his History of irish Periodical Literature, Vol. 2 ([London: T. C. Newby 1867]), pp.373-74; cited in Ulysses: Annotated Edition, ed. Sam Slote, et al. (Alma Classics 2011), “Aoelus”, n.26.

[ top ]