Life

| 1656-98; b. Dublin; son of a lawyer and landowner who was also an accomplished mathematician; br. of Sir Thomas; entered TCD 1671, studied maths and science and immersed himself in Descartes, Gassendi and Bacon and later Locke - of whom he wrote: Molyneux also states, in the same paragraph, that ‘no age has seen a more admirable piece” than Locke’s Essay’; grad. B.A., 1674; elected the first sec. of TCD Phil. Soc., which he founded with William King; Middle Temple, (London) 1675-78; translated Descartes’s Meditations (London 1680); returned to Dublin and was appt. Surveyor-General. of the King’s Buildings, 1684-88; quit Ireland for Chester during the Jacobite administration, 1689; appt. Commissioner of Army Accounts, 1690; elected MP for Dublin Univ. 1692 and 1695; fnd. member Dublin Philosophical Society with Sir William Petty and twelve others incl. Narcissus Marsh (among whom Mark Baggot was the sole Catholic), meeting first in a coffee house, 1683 [var. 1684]; developed the Dublin Hygroscope to measure moisture in the atmosphere; DPS reaches 34 members by 1685, with premisses in Crow St.; |

|

| commenced correspondence with Pierre Bayle, 1687; cessation of Society’s affairs when the ‘distracted state of the kingdom dispersed [the members] in 1688’ (TRIA, 1787), not to be renewed until 1707; exchanged letters with Locke, 1692-98 [publ. in ; influenced by Locke’s theory of government by contract in Two Treatises of Government (1690); Irish MP for Dublin City, 1692, and for Dublin University, 1695; strenuously opposed prohibitory rights of English parliament affecting Irish woollen exports; conveyed the copy of Richard Plunkett’s Gaelic-Latin dictionary to Edward Lhuyd, under heavy conditions, c.1695; his treatise on optics publ. as Diotrica Nova (1692), on refraction and lens-grinding written in collaboration with the Royal Astonomer Flamstead and with Halley, who added his method of establishing the “face” of optical lens; exchange numerous letters with his "excellent friend" John Locke (pref., Case of Ireland), whose opinions he adduces to support his argument in the Case; issued as Some Familiar Letters between Mr Locke and Several of His Friends (London 1708); |

| Molyneux went on to publish The Case of Ireland’s Being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated (1698), a pamphlet arising from the restrictive woollen laws of 1697 and treating of the deleterious effects of English legislation on Irish industry at larger - thus inaugurating the criticism of laws restricting Irish exports to English ships - dedicated to William of Orange and purportedly burned by the common hangman - the fate of Christianity not Mysterious (1696) by John Toland [q.v.] which Molyneux himself reported in a letter to John Locke - but actually a rumour about his own book (Case of Ireland &c.), now known to have been started by Charles Lucas [q.v.]; The Case was condemned by Westminster Parliament and Molyneux spent five weeks lodging with Locke during the ensuing fracas; he later wavered on the question of the Union with Great Britain; Molyneux died on his return to Dublin, Oct. 1698; |

| a reprint edition of 1782 - the year of Legislative Independence for Ireland - was issued in Dublin with additional material by Owen Roe O’Nial (pseud. of Joseph Pollock), and in unsigned introduction, 1782; the definitive edition of Molyneux’s The Case of Ireland’s Being Bound [... &c] has been edited by Patrick Hyde Kelly (Dublin 2018). RR CAB ODNB JMC DIB FDA OCIL |

|

[ top ]

Works

|

| Modern edns. & trans. |

|

| See also |

|

Bibliographical details

The Case for Ireland’s being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England Stated / by William Molyneux, of Dublin, Esq.; Dublin, printed by Joseph Ray, and are to be sold at his Shop in Skinner Row (MDC XC VIII) [see details of NLI presentation copy in Notes, infra].The case of Ireland's being bound by acts of Parliament made in England, stated: by William Molyneux ... Also, a small piece on the subject of appeals to the Lords of England, by the same author, never before published. To which are added, Letters to the men of Ireland, by Owen Roe O'Nial (Dublin M,DCC,LXXXII [1782], 93, [1]pp.; 8° [20cm]) [available at Internet Archive - online].

The Case for Ireland’s being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England Stated. [rep. of 1st edn.] as J. G. Simms, ed. & intro., with an afterword by Denis Donoghue [Irish Writings from the Age of Swift, 5] (Dublin: Cadenus Press 1977), 148pp., ill [lim. edn. 350 copies. Note: The work was dedicated to William of Orange.]

See also French trans. of same as Discours sur la sujétion de l'Irlande aux lois du Parlement d’Angleterre (Caen: Presses universitaires de Caen 2015), 160pp.[J.G. Simms & Denis Donoghue, eds.; trans. Pierre Gouhier.]

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

| Long reads: |

|

[ top ]

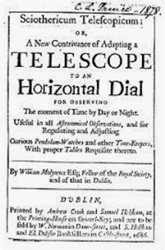

| Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies, Vol.II [of 2] (London & Dublin 1821), pp.433-37: ‘[...] Soon after his return from abroad [in Holland, Germany and France] he [Molyneux] printed at Dublin in 1686, his “Sciothericum Telescopium,” containing the description of the structure and use of a telescopic {435}

dial invented by him; another edition of which was published at London in 1700, 4to. On the publication of Sir Isaac Newton’s “Principia,” the following year, 1687, our author was struck with the same astonishment as the rest of the world; but declared also, that he was not qualified to examine the particulars. The celebrated Halley, with whom he constantly corresponded, had sent him the several parts of this inestimable treasure as they came from the press, before the whole was finished, assuring him that he looked upon it as the utmost effort of human genius. In 1688, the Philosophical Society at Dublin was broken up and dispersed by the confusion of the times. Mr. Molyneux had distinguished himself as a member of it from the beginning, by several discourses upon various subjects; some of which were transmitted to the Royal Society at London, and afterwards printed in the “Philosophical Transactions.” In 1689, among great numbers of other protestants, he withdrew from the disturbances in Ireland, occasioned by the severities of Tyrconnel’s government; and, after a short stay in London, fixed himself with his family at Chester. In his his retirement he employed himself in putting together the materials he had some time before prepared, for his “Dioptrics,”[sic] in which he was much assisted by Flamstead; and, in August 1690, went to London to put it to press, the sheets being revised by Halley, who, at our author’s request, gave leave for printing in the appendix, his celebrated theorem for finding the face of optic glasses; accordingly the book made its appearance in 1692, in 4to, under the title of “Dioptrica Nova.” |

| [...] |

| As soon as the public tranquillity was settled in his native country, he returned home; and upon the convening of a new parliament in 1692, was chosen one of the representatives for the city of Dublin. In the next parliament, in 1695, he was chosen to represent the Uni{436}versity there, and continued to do so to the end of his life; that learned body having, soon after his election, conferred on him the degree of Doctor of Laws. He was likewise nominated by the lord-lieutenant one of the commissioners for the forfeited estates, to which employment was annexed a salary of £500 ayear; but looking upon it as an invidious office, and not being a lover of money, he declined it. In 1698, he published, "The Case of Ireland stated, in Relation to its being bound by Acts of Parliament made in England," in which he is supposed to have delivered all or most that can be said upon the subject with great clearness and strength of reasoning. This piece (a second edition of which, with additions and emendations, was printed in 1780, 8vo.) was answered by John Cary, merchant of Bristol, in a book, called, "A Vindication of the Parliament of England, &c." dedicated to the Lord Chancellor Somers; and by Atwood, a lawyer. Of these, Nicolson remarks, that the merchant argues like a counsellor at law, and the barrister strings his small ware together like a shop-keeper. What occasioned Molyneux to write the above tract, was his conceiving the Irish woollen manufactory to be oppressed by the English government; on which account be could not forbear asserting his country’s independency. He had given Mr. Locke a hint of his thoughts on this subject before it was quite ready for the press, and desired his sentiments upon the fundamental principle on which his argument was grounded; in answer to which that gentleman, intimating that the business was of too large an extent to be the subject of a letter, proposed to talk the matter over with him in England. This, together with a purpose which Molyneux had long formed of paying that great man, whom he had never yet seen [...] (pp.436.) |

| See full copy in RICORSO Library > Criticism> History > Legacy - via index or as attached. |

| Thomas Davis, “The Irish Parliament of James II”, in Rolleston, ed., Selections from his Prose and Poetry (London 1914; NY 1915) [on the Acts of that parliament:] ‘But their next act deserves more notice. It must not be forgotten that Molyneux’s Case of Ireland, which the parliaments of England and Ireland first burnt, and ended by declaring and enacting as sound law, was published in 1699, just ten years after this parliament of James’s. Doubtless the antique rights of the native Irish, the comparative independence of the Pale, the arguments of Darcy, the memory of the council of Kilkenny, might suggest to Molyneux those principles of independence, which one of his cast of mind would hardly reach by general reasoning. But why go so far back, and to so much less apt precedents? Here, in the parliament of 1689, was a law made declaring Ireland to be and to have always been a “distinct kingdom” from England; “always governed by his majesty and his predecessors according to the ancient customs, laws, and statutes thereof, and that the parliament of Ireland, and that alone, could make laws to bind this kingdom”; and expressly enacting and declaring that no law save such as the Irish parliament might make should bind Ireland. And this act prohibited all English jurisdiction in Ireland, and all appeals to the English peers or to any other court out of Ireland. Is not this the whole argument of Molyneux, the hope of Swift and Lucas, the attempt of Flood, the achievement of Grattan and the Volunteers? Is not this an epitome of the Protestant patriot attempts, from the Revolution to the Dungannon Convention? Is not this the soul of ’82? Surely, if it be, as it is, just to track the stream of liberation back to Molyneux, we should not stop there; but when we find that a parliament which sat only ten years before his book was published, which must have been a daily subject of conversation - as it certainly was of written polemics - during those ten years; when we find this upper fountain so obviously streaming into the thought of Molyneux, should we not associate the parliament of 1689 with that of 1782, and place Nagle and Rice and its other ruling spirits along with Flood and Grattan in our gratitude?’ (Chap. III[pp.1-73] |

[ top ]

| Thomas Mooney, A History of Ireland [...], 2 vols. (Boston: Donahoe 1853), Vol. I - writes in his round-up chapter on Irish historians: ‘William Molyneux was born in Dublin, and has published many excellent works. Amongst others, one upon the State of Ireland, was dedicated by him to the Prince of Orange: he proves in it that that country was never conquered by Henry the Second; that he granted, according to treaty, a parliament and laws to such of the people of Ireland as resided in his pale; that the ecclesiastical state in that country was independent of England, and that the English could not bind the Irish by laws made where the people had not their deputies.’ (Op. cit., p.120; available online. |

Russell Alspach, Irish Poetry from the English Invasion to 1798 (Phil: Pennsylvania UP 1959), pp.75ff; incls. bibl.: Robert Burrowes, ‘Preface’ to Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol. 1 (1787), p.xiii; also Samuel Ayscough, ‘Minutes and Register of the Philosophical Society of Dublin, from 1683 to 1687, with copies of the papers read before them’, itemising Molyneux’s contributions as ‘Concerning Lough-Neagh, and its petrifying quality’; ‘A way of viewing pictures in miniature’; and ‘Queries relating to Lough Neagh’ (Transactions, 1787, pp.473-74). Note that Alspach holds that The Case of Ireland was ordered to be burnt in the palace yard in Dublin, ‘for it was to be many years before Englishmen stopped looking askance at Irshmen who had the temerity to stand up for their country. But Molyneux’s pamphlet circulated widely; it pointed the way to eventual independence.’ (Alspach, p.76).

Patrick Kelly, ‘Lock and Molyneux, the anatomy of a friendship’, in Hermethena, 126 (Summer 1979), pp. 38-54: ‘The friendship between the philosopher Locke and the Dublin scientist and writer on politics, William Molyneux, is known to the world through their correspondence, published in 1708 as the majpr part of the Familiar Letters between Mr Lock and several of his friends and rerpinted in each of the fourteen eidtions of Locke’s Works that appewared between 1714 and 1826.’ Kelly goes on to speaks about the attractive aspect of the correspondence, its warmth, good sense and urbanity, but remarks on hidden tensions which culminated in the publication of Molyneux’s famous pamphlet, The case of Ireland’s being bound by Act of Parliament in English’, ‘a work generally regarded as the pioneer statement of what later became known as “colonial nationalism”.’ (p.38. available at JSTOR - online; accessed 29.01.2024.)

W. B. Stanford, Ireland and the Classical Tradition (IAP 1976; 1984), William Molyneux founded Dublin Philosophical Society in 1683, lasted only six years [see also seq., under Thomas Molyneux and James Caulfeild, Earl of Charlemont] [70]. Further: William Molyneux, scientist, Dioptrica Nova, &c (London 1692), in the introduction condemns ‘the commentators on Aristotle’ for rendering ‘Physics an heap of froathy Disputes’ though Aristotle was ‘certainly himself a most diligent and profound investigator of Nature’. He also explains that he has written in English because he is ‘sure that there are many ingenious Heads, great Geomaters and masters in Mathematics, who are not so well skill’d in Latin.’ [190]

A. N. Jeffares, W. B. Yeats, A New Biography (1988), notes that Yeats links Swift with Molyneux. in his Introduction to Words Upon the Window-Pane (1934; Jeffares p.300).

D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland (London: Routledge 1982), quoting his Case to the effect that the ‘original compact’ between Henry II and the people of Ireland was ‘that they should enjoy the like liberties and immunities, and be governed by the same ... laws, both civil and ecclesiastical, as the people of England.’; further insisting on the connection to the imperial crown to which ‘we must ever owe our happiness’, while Ireland had always enacted statutes relating to this succession ‘by which it appears that Ireland, to annexed to the Crown of England has always been looked upon to be a Kingdom complete in itself, and to have all jurisdiction to an absolute kingdom belonging and subordinate to no legislative authority on earth’. (p.102; remarking furrther that Swift took up this theme.)

Joseph Th. Leerssen, Mere Irish & Fior-Ghael: Studies in the Idea of Irish Nationality, Its Development and Literary Expression Prior To The Nineteenth Century (Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub. Co. 1986), remarks on William Molyneux, The case of Ireland’s being bound by acts of parliament in England (1698), arising from the trade restrictions and especially the wool bill being discussed in the House of Commons. Molyneux was also translated Descartes’ Meditations into English and was a correspondent of John Locke. His argument regard the rights of the Irish parliament turns on the difference between planters and Gaels, ‘supposing Henry II had Right to invade this Island, and that he had been oppos’d therein by the Inhabitants, it was only the Ancient Race of the Irish, that could suffer by their Subjugation; the English and Britains, that came over and Conquer’d with him, retain’d all the Freedoms and Immunities of Free-born Subjects. (p.19-20). The dedication asserts, ‘Your Majesty has not in all Your Dominions a People more United and Steady in your Interest than the Protestants of Ireland.’ But those Old English who had established parliamentary practice had generally remained Catholic and Stuart supporters [342]. The Case of Ireland elicited criticism in English responses such as Case of Ireland, An Answer to Mr Molyneux (London 1698), where the inference was ironically made that if Molyneux was right the Irish parliament should be filled with Old English. Molyneux’s book can be counted as one of the first instances of the effect of Enlightenment thought on British politics, since it addresses questions of the reciprocal rights and duties of citizen and government. The celebrated core of Molyneux’s declamatory view is this, ‘that Ireland should be bound by Acts of Parliament made in England, is against Reason, and the Common Rights of all Mankind. All men are by Nature in a State of Equality, in Respect of Jurisdiction or Dominion, this I take to be a Principle in it self so evident, that it stands in need of little Proof. ... [a maxim] so inherent to all Mankind, and founded on such Immutable laws of Nature and Reason, that ‘tis not be be Alien’d or Given Up, by any Body of Men whatsoever.’ The source is his friend Locke’s [anonymous] Treatise on Government, and a number of Molyneux’s arguments echo that text almost verbatim. (Leerssen, op. cit., pp.343-45]

Davis Coakley, Irish Masters of Medicine (Town House ?1993), William Molyneux, Robert Boyle, and Allen Mullen founded the Dublin Philosophical Society along Baconian lines - Molyneux’s rules are like a extract from Novum Organum and his economic plan for Ireland was as a range for sheep and beef supplying England. [Mullen, q.v.]

Jim Smyth, ‘Anglo-Irish Unionists Discourse, c.1656-1707: From Harrinton to Fletcher’, in Bullán: An Irish Studies Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Summer 1995), esp. p.24-26: [...] Moylneux’s reputation rests on the influence which the Case exercised amongst eighteent-century Irish na American patriots and on its contribution to the [24] history of political thought. But, as a cononical, free-standnig text, the Case presents certain puzzles, notably the stray single-sentence endorsement of union and the rehetorical near-elimination of the Catholic population. ... it is celar that union as a means to an end did not necessarily conflict with the defence of the Irish parliament, viewed as a means to the same end. It is equally clear that the minimising of Catholic numbers was not quite a “bare-faced” “evasion”, or at least not an original or even an unusual one. [Discusses contempoary criticisms brought to bear on the Case by William Atwood and Simon Clement.] ‘Atwood and Clement ... were no more troubled by the inconsistency of excludnig the colonists (or natives) from the liberaties which they claimed for themselves, than was Molyneux by the inconsistency of excluding Catholics from the liberties which he claimed for all mankind. Colonies were perceived as a potential threat [...]’ (pp.24-25.)

[ top ]

Two witnesses ..

[ top ]

Ian Leask, ‘“A Matter of Dangerous Consequence”: Molyneux and Locke on Toland’, in Between Secularization and Reform Religion in the Enlightenment, ed. Anna Tomaszewska [Brill's Studies in Intellectual History, 340 (Brill Print Publication 2022): "William Molyneux’s attitude to John Locke, as demonstrated by their cor- respondence, might appear to be that of a fawning acolyte: on the face of it, Molyneux’s reverence at times leaves him almost prostrate. Certainly, Locke makes important changes to the Essay Concerning Human Understanding as a direct result of Molyneux’s queries. Nonetheless, reading Molyneux’s own account, there is no mistaking the seniority of Locke: in 1694, for example, Molyneux declares that “a man of greater candour and humanity [than Locke] there moves not on the face of the earth.” Three years later, Molyneux tells Locke (on 17th Sept. 1697) about the portrait of him (Locke) that hangs in his dining room in Dublin - and also that Robert Molesworth is wont to call by in order to “pay his Devotion”! (Even allowing for the exaggerated conventions of epistolary discourse, this depiction of philosophical worship remains strikingly strange.) Despite the genuine reverence evidenced here, closer analysis of the Locke-Molyneux correspondence regarding the very particular case of John Toland, and the events and misadventures that characterized Toland’s sojourn in Dublin in 1697, reveal a different aspect to Molyneux’s attitude. As I want to show in this chapter, it seems that Molyneux refused to accept the “abandonment” of Toland that Locke more or less commands; moreover, he sought to defend Toland, in part, upon the basis of Locke’s own philosophical-political principles - thereby showing himself to be (on this occasion, at least) more Lockean than Locke himself. To make this case, I begin by providing some wider biographical and contex- tual information about both Molyneux and Toland. I then outline, first, the way in which Toland’s most famous (or infamous) text, Christianity Not Mysterious, [219] draws on important Lockean conceptions to construct its case against conven- tional religious views and, secondly, the kind of backlash that this “borrow- ing” produced, against Locke himself, as well as Toland. With this established, I offer a narrative account of the relevant sections of the Molyneux-Locke corre- spondence, showing Locke’s increasing irritation with the trouble that Toland (and their perceived association) had generated.

Of the mid-1690s: This was a particularly turbulent period, in terms of the wider theological-political conjunction: the attempt to restore a Catholic monarchy in Britain and Ireland had been defeated; the Anglican Church was determined to cement its hegemony; Irish Protestants also wanted to ensure that their parliament in Dublin enjoyed “equal rights” alongside Westminster. It was within this context that Molyneux produced his The Case of Ireland’s Being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated, in 1698. The book, which made solid use of Molyneux’s legal training (and, to some extent, his appreciation of Locke’s political philosophy), set out the case for legislative independence for Dublin, and was duly condemned by the London parliament [...]" . [Available online; accessed 29.01.2024.]

(Ftns. incl. Capel Molyneux, An Account of the Family and Descendents of Sir Thomas Molyneux (Evesham: 1820); Correspondence of John Locke, 8 vols. (Oxford 1976-1989); Patrick Hyde Kelly’s definitive edition of the text: William Molyneux’s The Case of Ireland’s Being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated (Dublin: 2018).

| Molyneux’s Question |

| Gabriele Ferretti & Brian Glenney, eds., Molyneux's Question and the History of Philosophy (London: Rouledge 2021), 370pp. |

INTRODUCTION: The editors of the collection begin by speaking about ‘the question posed by William Molyneux [..] to John Locke, in a private letter of 1693.’: ‘This “jocose problem” - as Molyneux himself considered it - was published by Lock in the second edition of his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1694). His formulation (hereater MQ) is very well known [quoting Locke]: [“]‘Suppose a man born blind, and now adult, and taught by his touch to distinguish a cube and a sphere of the same metal, and nighly of the same bigness, so as to tell, when he felt one and the other, which is the cube, which the sphere. Suppose then the cube and sphere placed on a table, and the blind man made to see: quaere, whether by his sight, before he touched them, he could now distinguish and tell which is the globe, which the cube?’ To which the acute and judicious proposer answers: ‘Not. For, though he has obtained experiewnce of how a globe, how a cube affect his touch, yet he had not yet obtained the experience, that what affects his touch so or so, must affect his sight so or so; that a protruberant angle in the cube, that pressed his hand unequally, shall appear to his eye as it does in the cube.’ I agree with this thinking gentleman, whom I am proud to call my friend, in his answer to this problem; and am of opinion that the blind man, at first signt, would not be able with certainty to say which was the globe, which the cube, whilst he only saw them; though he could unerringly name them by his touch, and certainly distinguish them by the difference of their figures felt.”’ (Locke's Corr., II, IX, 8.) |

| Manuel Fasko & Peter West, Molyneux’s Question The Irish debates”, in Molyneux's Question and the History of Philosophy , ed. Ferretti & Glenney (Rouledge 2021), Chap. 7: |

|

| Book details available at publisher - online; also as full text at ProQuest. |

[ top ]

Quotations

The Case of Ireland’s Being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated (1698): ‘The subject therefore of our present disquisition shall be How far the Parliament of England may think it reasonable to intermeddle wiwth the affairs of Ireland and bind us up by Laws in their House’ (1725 Edn.,p.36.) ‘It seems not to have the least Foundation or Colour from Reason or Record: Does it not manifestly appear by the Constitution of Ireland, that ‘tis a compleat Kingdom within it self? Do not the Kings of England bear the Stile of Ireland among the rest of their Kingdoms? Is this agreeable to the Nature of a Colony? Do they use the title of Kings of Virginia, New England, or Mary-Land? Was not Ireland given by Henry the Second in a Parliament at Oxford to his Son John, and made thereby an absolute Kingdom, separate and wholly independent of England, ‘till they both came United again in time, after the Death of his brother Richard without Issue? have not Mulititudes of Acts of parliament both in England and in Ireland declared Ireland a compleat Kingdom? Is not Ireland stiled in them all, the Kingdom or Realm of Ireland? Do these Names agree to a Colony? Have we not a Parliament, and Courts of Judicature? Do these things agree with a Colony? (p.100.) ‘We are supremely bound to obey the Supream Authority over us; and yet we are not permitted to know Who or What the same is; whether the Parliament of England, or that of Ireland, or Both; and in what Cases the One, and in what the Other: Which Uncertainty is or may be made a Pretence at any time for Disobedience. It is not impossible but the different Legislations we are subject to, may enact different, or contrary Sanctions: Which of these must we obey?’ (p.116.) [All quoted in A. N. Jeffares, ‘Swift and the Ireland of His Day’, in Images of Invention, Gerard Cross: Colin Smythe 1996, p.4ff.)

The Case of Ireland’s Being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated (1698), written from the standpoint of the ‘Publick Principle’, insists that ‘All men are by nature in a state of equality’ and therefore ought be ‘free from all subjection to positive laws till by their own consent they give up their freedom by entering into civil societies’; and further that ‘we [in Ireland] have had Parliaments in Ireland since very soon after the invasion of Henry II’ and should continue to do so. [&c.] Further: ‘[T]hat Ireland should be bound by Acts of Parliament made in England, is against Reason, and the Common Rights of all Mankind. All men are by Nature in a State of Equality, in Respect of Jurisdiction or Dominion, this I take to be a Principle in it self so evident, that it stands in need of little Proof. ... [a maxim] so inherent to all Mankind, and founded on such Immutable laws of Nature and Reason, that ‘tis not be be Alien’d or Given Up, by any Body of Men whatsoever.’ (Quoted in Joep Leerssen, Mere Irish & Fior-Ghael, 1986 [see infra].)

The English in Ireland: ‘If the English in Ireland be treated as Englishmen, they will be Englishmen still in their hearts and inclinations, but if they be oppressed, they will turn Irish, for fellowship in suffering begets love and unities interests.’ (Marsh’s Library Mss. Z.3.25, 312, No.79; quoted Caroline Robbins, The Eighteenth-Century Commonwealthman, 1961, Harvard UP, p.146; cited in Denis Donoghue, We Irish: Essays in Irish Literature and Society, Cal. UP, 1986, p.17 [note O’Donoghue’s previous writings on Molyneux, supra.]).

[ top ]

References

D. J. O’Donoghue, Poets of Ireland (Dublin: Hodges Figgis 1912), asserts that Canon O’Hanlon edited The Case of Ireland [n.d.], not so listed under O’Hanlon in BML.

Dictionary of National Biography, Molyneux family members Edmund, Richard, and Richard Viscount Maryborough. Extract from The Case in Justin McCarthy, ed., Irish Literature (1904). NOTE also, The Case is summarised enthusiastically in Thomas Campbell, Philosophical Survey of the South of Ireland (1778).

Roy Foster, Modern Ireland (London: Allen Lane 1988), p.118, b. Dublin, ed. TCD; first sec. of TCD Phil. Soc. [fnd. by William King]; surveyor general, 1684; retired to Chester, 1689; Army Accounts Commissioner, 1690; Dublin Univ. MP, 1692-95; Case of Ireland Stated (1698) on effects of English legislation on Irish industry, purportedly burned by the common hangman [a rumour started by Charles Lucas, acc. to Sean Connolly]. See Samuel Molyneux, supra, and also Patrick D’Arcy, whose Argument (1643) anticipates the Case.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day Co. 1991), Vol. 1, selects Two Letters to John Locke [768-70]; The Case of Ireland’s Being Bound ... Stated [871-73]. Remarks: Francis Hutcheson discusses the Molyneux problem [regarding a blind man and colours], 786; [eds. Carpenter et al., Molyneux remote from racialist nationalism, 856, 858]; Domville compared to, 862; note to The Case, Introduction & Conclusion [870]; Lucas espouses principals of [903]; Henry Grattan, ‘The excellent tract of Molyneux was burned - it was not answered; and its flame illumined posterity’ (Speech of 16 April, 1782) [921]; [biogs, 956]; Dublin Philosophical Society fnd. Molyneux and Petty, 1683, 967. WORKS & CRIT [as supra]. FDA3 incls. remarks of Seán O’Faolain: ‘you will not find as much as the word “Gael” in Swift, Molyneux, &c. [570]. Also Marianne Elliott: ‘Molyneux’s Case &c portrayed the bitter disappointment at the outcome of the Glorious Revolution for Ireland and became one of the key documents in the protestant ‘patriot’ campaign culminating in ... legislative independance in 1782-83’[...] Molyneux had argued that the orginal compact had been made between the Irish peole and the English king at the time of Henry II’s conquest of Ireland ... consequently they owed no allegiance to any intermediary bodies and that the English parliament had no right ... Molyneux applied the concept of no taxation without representation similiar to the American situatation ... in that golden age of confident protestant liberalism, the 1770s and 1780s’ [Marianne Elliott, ‘Watchmen in Zion: The Protestant Idea of Liberty’ (Field Day Pamphlet, 1985); FDA3, p.606]. Further, the resurgence of the Irish nation primarily a Protestant affair, owing its origins to the writing of William Molyneux (et al.) [Luke Gibbon, ed., FDA3, p.954.]

Library Catalogues

| Marsh’s Library holds Case of Ireland’s being Bound ∓c (1698; rep. London 1720; rep. Dublin: Cadenus 1977); copy of 1698 octavo edn. presented by the author to Dr. Bouhéreau. |

| Belfast Linenhall Library holds The Case against Ireland’s being bound by Acts of Parliament in England, Stated (1698, also 1725, 1749, 1782). |

| Belfast Central Public Library holds Case of Ireland (1725); de Burca Cat, Case, printed Ray, Dublin 1698, £275.00. |

[ top ]

Notes

Spirit of Molyneux!: Grattan called out in the triumphal peroration of his speech on legislative independence in 1782: ‘Spirit of Swift! Spirit of Molyneux! Your genius has prevailed. Ireland is now a nation. In that new characters I hail her, and bowing to her august presence, I say, Esto perpetua!’

Sybil le Brocquy Commemorative Committee: a presentation copy of was acquired by the Sybil le Brocquy Commemorative Committee and presented to the National Gallery of Ireland in 1974. Bibl., The Case for Ireland’s being Bound by Acts of Parliament in England Stated / by William Molyneux, of Dublin, Esq.; Dublin, printed by Joseph Ray, and are to be sold at his Shop in Skinner Row (MDC XC VIII). The copy belonged to William King and later passed to William Shaw Mason who had it bound in dark green Morocco (prob. by George Mullen), before presenting it to Earl of Charlemont when Lord Lieutenant[ top ]

Jonathan Swift described Molyneux as ‘an English gentleman born in Ireland’ who ‘never grew tired of proclaiming the fact’ (quoted in Joep Leerssen, Mere Irish and Fíor Ghael, Amsterdam, 1986, p.350.

Dublin Philosophical Soc.: founded by Molyneux et al., given in Muriel McCarthy, Hibernia Resurgens: Catalogue of Marsh’s Library (Dublin 1994), p.10: In 1667 they began a correspondence with Pierre bayle, but this lapsed when “the jealousy, suspition & prospect of troubles in this kingdome have such unhappy influence on our philosophical endeavours,that little of worth has of late been done among us.’ (St. George Ashe to Wm. Musgrave, sec. of the Oxford Soc., 15th July 1687).

Antecedents: Patrick D’Arcy’s Argument (1643) anticipates the substance of Molyneux’s Case (1698); see also Anthony Dopping, Modus tenendi parliamenta in Hibernia (1692), to which Moyneux refers in his famous work.

[ top ]