Life

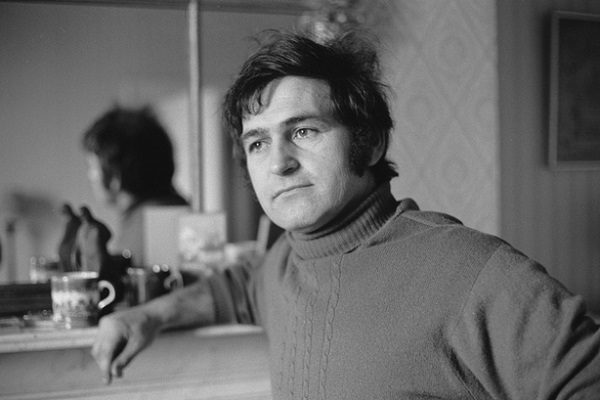

| 1935- [var. 1936; Thomas Bernard Murphy]; b. 23 Feb., Tuam, Co. Galway; youngest of ten children; ed. in local National School to 1950; ed. Technical College as fitter-welder at afterwards apprenticed to state-operated sugar factory in Tuam; proceeded on scholarship to TTC in Dublin, and trained as metalwork teacher; involved with Tuam Little Theatre Guild, 1951-62; taught at Mountbellew Vocational School, Co. Galway, 1957-62; moved to London as writer, 1963-71; |

| with Noel O’Donoghue, wrote On the Outside (1959), a one-act play dealing with two young men excluded from a dance hall, first performed in Cork, winner of All-Ireland Amateur Drama Competition, Athlone, 1960 [priaze of 15 guineas]; broadcast on RTÉ, 1962; followed with The Iron Men, deal with an Irish family transposed by exile to an English suburb (‘the House of Carney’), afterwards revised as A Whistle in the Dark; won All-Ireland script prize in 1961 but rejected by Ernest Blythe at the Abbey with a dismissive notice, 1960; later produced by Joan Littlewood at Theatre Royal (Stratford East), London, 1961; transferring to the West End; greeted by Kenneth Tynan it was ‘arguably the most uninhibited display of violence that the London stage has ever witnessed’; played at the Olympia Theatre, Dublin, 1962 and in America in 1969 taking the Time Magazine ‘Play of the Year’ nomination; |

| wrote The Fooleen, later renamed A Crucial Week Week in the Life of a Grocer’s Assistant, also rejected by the Abbey, 1961; moved to England to become a full-time writer, 1962; his television plays for BBC incl. The Fly Sham, in which T. P. McKenna appeared; issued Famine (Peacock Theatre, 28 March 1968), dir. Tomás Mac Anna, a treatment of the historical events of 1846-47 centred on the complex character of John Connor, which focuses on spiritual degeneration - the ‘other “poverties” that attend famine’ (Murphy, Intro.); revived Gary Hynes (Abbey 1993), with Gabriel Byrne in the lead,and successfully toured, giving rise the a memorial plaque in the Abbey bar; presented A Crucial Week in the Life of a Grocer’s Assistant (Abbey 1969); returned to live in Ireland, Spring 1970; |

| presented The Morning After Optimism (Abbey 1971), concerning the violent mutual antagonism of James and Rosie, a pimp and a prestitute who murder their opposites Edmund and Anastasia; The White House (1972) was a failure in Dublin; IAL Award, 1972; appt. Director of Abbey, 1973; On the Inside (1974), companion piece to On the Outside; followed by The Sanctuary Lamp (Abbey 1975), the controversial play of the Dublin Theatre Festival for that year, defended by Cearbhail Ó Dálaigh [President of Ireland]; wrote The J. Arthur Maginnis Story (1976) [var. 1977], for “The Dubliners” (Luke Kelly et al.); also The Blue Macushla (1980), with programme notes by Fintan O’Toole; adapted Liam O’Flaherty’s Informer for the stage (Dublin Theatre Festival, 1981; pub. 2008), with Liam Neeson as Gypo Nolan; adapted Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer (Abbey Th. 1982); also wrote The Patriot Game, commissioned by the BBC for the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, though never produced, but published as a play, 1991; Famine revived (Seapoint Ballroom, 1984); |

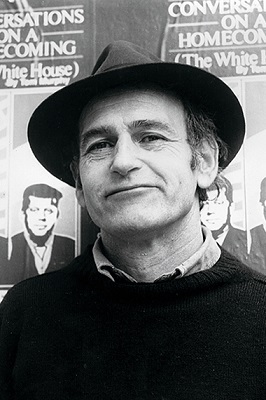

| wrote Conversations on a Homecoming (1985), in which disillusioned 1960s idealists welcome one of their number, Michael, back from America; appt. Druid Theatre Co. writer-in-residence, Sept. 1983; wrote The Gigli Concert (Oct. 1983), in which JWP King, a washed-up dynamatologist, is visited in his rooms by an Irishman who spends his days steeped in ‘corruption, brutality, backhanding, fronthanding’ as a jobbing builder but is nevertheless possessed by the spirit of possessed by the spirit of the operativ singer Beniamino Gigli; played by Tom Hickey and Godfrey Quigley; winner of Harvey and Independent Newspapers Awards; wrote Bailegangaire (1985) - meaning ‘the house without laughter’, and concerning ageing Mommo’s bedridden recitation of the epic tale of a village laughing match to two daughters variously struggling to escape the personal and collective past that she embodies; produced successfully by Druid in Galway with Siobhán McKenna as ‘Mommo’ (Dec. 1985), and transferrd to London (Feb. 1986) before returning to the Gaiety in Dublin (May 1986) |

| issued Too Late for Logic (1989); The Gigli Concert successfully revived (Abbey 1990); Out the Outside revived at the Peacock, with On the Inside, as a companion piece and sequel, 1992; issued novel, The Seduction of Morality (1994), a novel dealing with the homecoming of an Irish-American prostitute to her small-town bourgeois family to bury her grandmother and settle family property; adapted Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield as She Stoops to Folly (Abbey 1996), dir. Patrick Mason; presented The Wake (Abbey, Feb. 1997), a stage version of The Seduction of Morality; The Gigli Concert revived in Galway by Sugán Theatre Co., Double Edge Theatre, 9-26 May 1996; subject of a six-play “Celebration of Tom Murphy” which took place at the National Theatre (Abbey) in October 2001, accompanied by a symposium on his art (Mairtín Ó Cadhain Lecture Th., TCD) under the direction of Professor Nicholas Grene; Murphy’s notebooks were acquired by the TCD Library in the same period; issued The Drunkard (2004), a version; |

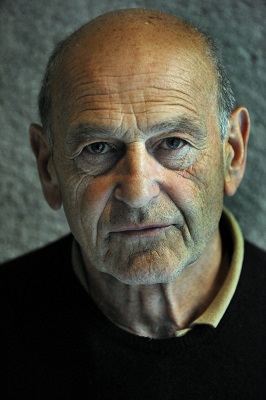

| Murphy is the subject of a programme in the RTÉ Lyric “Playwrights in Profile” series (prod. Sean Rock, 10 July 2007); there is a portrait of Murphy by the RHA President Cary Clarke in the foyer of the Abbey; Gigli Concert revival directed by Gary Hynes, with Denis Conway as The Irishman, Pete Sullivan as JPW King, and Eileen Walsh as Mona, 2009; prem. The Last Days of a Reluctant Tyrant (Abbey Th., June 2009), dir. by Conall Morrison, portraying a peasant woman, Arina, who married into a decaying aristocratic family, bringing to it the Kulak ethos of ‘property, land, money’, and who now faces ruin in the form of her worthless sons; Colm Tóibín has called Murphy ‘the nearest thing we have to genius’; Murphy appeared against a theatre curtain in an Irish 55c stamp of 2009; Druid Th. Co. produced DruidMurphy, a cycle consisting of Whistle in the Dark, Famine, and The Homecoming, all directed by Gary Hynes, opening in Galway Town Hall, 24 May 2012, and later touring to Hampstead Th. (London), Oxford, Washington and then Dublin (June-Oct. 2012); The House, premiered in 2000, was revived at the Abbey Theatre, dir. Annebelle Comyn (June 2012), with Declan Conlon playing Christy Cavanagh, a returning emigrant in the 1950s; |

| involved in physical tussle with Gate-proprietor Michael Colgan at the host’s 50th birthday party in Toibin’s house on Upr. Pembroke St., Dublin, 2005;a new play, Brigit, in which Seamus, husband of Mommo in Bailegangaire and hence a prequel, accepts a commission to make a sculpture of St. Brigid for the local church; produced jointly with Bailegangaire by Druid at Dublin Theatre Festival, 2014 - running at the Olympia Theatre (1-5 Oct. 2014); d. 15 May 2018, aetat 83. DIW DIL FDA OCIL WJM |

|

|

[ top ]

Works| Plays | |

|

|

| Selected editions | |

|

|

| Collected Plays | |

|

|

| Fiction | |

|

|

| Miscellaneous | |

|

[ top ]

Criticism| Full-length studies |

|

| Articles, reviews |

|

|

[ See also sundry unlisted reviews and remarks in Commentary, infra. ] |

[ top ]

Symposium, A Celebration of Murphy at the Abbey & Peacock (October 2001) being the 40th anniversary of the inaugural production of Tom Murphy’s first full-length play, A Whistle in the Dark (Theatre Royal, Stratford East), consisting in a six-play Murphy season in conjunction with an academic symposium held at Mairtín Ó Cadhain Lecture Theatre, Arts Building, TCD [see proceedings, infra].

Nicholas Grene, ed., Talking About Tom Murphy (Dublin: Carysfort 2002), 115pp., ill. ports. [incls. transcript of a interview between Murphy and Michael Billington (Guardian theatre-critic)); essays, by Fintan O’Toole (on Murphy’s writing methods); Chris Morash (on redemptive transformation); Shaun Richards (on use of Christian imagery to deconstruct Catholicism); Nicholas Grene (on The Gigli Concert), et al. [reviewed by Liam Harte, in The Irish Times , 9 Nov. 2002, “Weekend”, 2001].

[ top ]

|

|

Fintan O’Toole, The Politics of Magic: The Work and Time of Tom Murphy (Dublin: Raven Arts Press 1987): ‘In Tom Murphy’s work, however, damnation and salvation are not irreconcilable opposites; rather the former is a precondition to the latter [e.g. The Gigli Concert].’ (p.167).

Ed Cairns & Shaun Richards, Writing Ireland (1988), - on Bailegangaire (1986): ‘The means by which Murphy dramatises this national paralysis is through the brilliant device of having the old woman, Mommo, locked into a narrative the conclusion of which she is incapable of facing, and her grandaughter [sic], Mary, recognising that only by ending the narrative will harmony return ... Mommo’s story is a powerful and moving evocation of a desolate existence bereft of poetry or passion, in which only by laughing at their lot has survival been made feasible.’ (p.151.)

D. E. S. Maxwell, Critical History of Modern Irish Drama 1891-1980 (Cambridge UP 1984), writes that The Gigli Concert represents ‘the collisions between savage actualities of failure and despair and the solace or defence offered by human faiths, rituals, fantasies - most often their incapacities.’ (pp.162-63.)

Fintan O’Toole, ‘Facing the audacity of despair’, in The Irish Times [Thursday], 5 Oct. 2001, p.12: Murphy writes ‘marvellously for actors’, citing Siobhán McKenna, Tom Hickey, Seán McGinley, John Kavanagh, and others [see infra]. He further remarks that Murphy fuses together the highly stylised story that the ancient, bedridden Mommo keeps telling but never finishes with the immediate personal and social concerns of her two grand-daughters, both disrupting the realistic setting and heightening the realism. Remarks of The Gigli Concert: ‘Murphy imagined the English cultist J. P. W. King and the despairing Irish property magnate who is his tempter and his accidental saviour in living Technicolor’, and speaks of the audience taking the same journey as King from ‘treating the Irishman’s desire to sing like the great tenor Gigli as an expression of dementia to seeing it as an obtainable, even inevitable goal’. On A Whistle in the Dark: ‘A stream of English theatre in the 1960s, passing through Pinter and Joe Orton’s Entertaining Mister Sloan, springs from what Murphy does in A Whistle in the Dark: turn the apparent familiarity of domestic drama into an arena for ferocious psychological and physical conflict.’ Of the direction: ‘The way the opening moments [...] brilliantly staged by Connall Morrison, almost tore apart the fabric of a naturalistic setting is a momentous declaration of intent.’ O’Toole speaks of the suitability of the Peacock stage and the intimacy it affords to The Sanctuary Lamp but, criticised the treatment of the ritualistic moments when Harry mimics the dance his dead daughter used to do and later lifts the church pulpit ‘after the biblical Samson’: ‘Here, these moments are oddly cramped and almost lost.’ Considers that Geraghty as Dada is ‘a cast too far against type to reach the almost gothic heights the play demands.’ The title phrase of this article is taken from the part of J. P. W. King.

Richard Kearney, Transitions: Narratives of Modern Irish Culture (Dublin: Wolfhound Press 1988), asserts: ‘Murphy has probed the dark recesses of modern Irish experience with unrelenting obsessiveness’ (p.161).

Gerald Fitzgibbon, Historical Obsession in Recent Irish Drama’, in The Crows Behind the Plough: History and Violence in Anglo-Irish Poetry and Drama, ed. Geert Lernout [Costerus Ser. Vol. 79] (Amsterdam: Rodopi 1991), pp.41-59, on Whistling in the Dark: ‘[...] when the Carneys, a tough Irish emigrant family, land in Coventry they avenge themselves for all the humiliations of their former lives in Ireland. The one member of the family who has tried to escape and form a new life for himself with his English wife, is inexorably drawn back into the old tribal pattern. The past wins and the play ends with one brother killing another. Dada, the author of the family myth of the fighting Carneys, may have been defeated, but the myth he generated has won.//Buried in the play is a deep ambivalence about tribal identity and individual authenticity.’ (p.57.)

[ top ]

Christopher Morash, ‘Sinking down into the Dark’, in in Bullán: An Irish Studies Journal, 3, 1 (Spring 1997), pp.75-86: ‘That basic, irreducible element of theatrical performance, the body of another human being, is thus revealed as the ultimate limitation on human freedom; at the same time, it is the only context in which such freedom makes any sense. / All attempts to stage the Famine enact this contradiction thorough the paly of presence and absence which is built into the heatre’s basic form. It is there in the tensions between those bodies standing before us in the immediate, physical present and the absent world of the offstage which holds time in abeyance, both as promise and threat, both as a utopian possibility for the future and as a reminder of human limitations inherited from the past. No attempt to stage the Famine, however, holds these elements in balance as clearly, consciously and powerfully as Murphy’s Famine. Murphy’s play reminds us that as we sink down into the darkened theatre during a staging of the Famine, it is this harsh dialectic, and not the easy sentimentality of an imagined sorrow, which must be reactivated, again and again.’ (p.84.)

Maurice Walsh, review of The Seduction of Morality (1994), in Times Literary Supplement (8 July 1994): Vera, now a call girl in New York, returns to small-town home where her family are pillars of society; Tom is ‘proud of his morals. He loved them.’ Declan, brother-in-law, is ‘healthily disgusted in his role as bank-clerk’; the Imperial Hotel has been left to her, to their horror; finely wrought set pieces depicts the hypocritical code that sustains the family but eats away their capacity for love; not until Vera reconnects with her early life and her grandmother that she finds strength to free herself; set in summer 1974; shards of social history include graves in Industrial School and the brothers and sisters committed by their families.

Patsy McGarry, interview with Tom Murphy, The Irish Times (15 Sept. 2001): ‘He likes to thing of himself as “writing music for the spoken voice” as “an aspirant composer of music”. This analogy of music crops up frequently in his conversation. “When I hear music, I hear an emotion. When I listen to a voice, I hear character”, he says. / “It is very exciting to try to find a pattern, rhythm, constraints, to find a symphony. / If seeking to recreated a mood, obviously the rhythm of what is being said has to complement that, but the problem is that punctuation is so sparse - the semi-colon (for instance) is ridiculous in a play - as against musical notation.”.’ Murphy speaks of the “nightmare” of writing involved in two “rhythms”, one “low and very circular”, the other “very fast”, not as “terrifying”, just “a fact.” Further, ‘This “casting of words together [meant that] until very recent times I could recite a play [on my own] from start to finish ... because it was like a musical score”. He would “deliberately, frequently, mix tenses to ensure a line is energised; that the actor has to change gears and animate the line”. Murphy speaks of prose as something that he doesn’t find easy and remarks, “English has long been a mystery to me. I haven’t constructed a proper sentence since we started talking, and perhaps you haven’t either”. Dismisses -isms imposed upon a play and condemns the “false expectations” of academics, professing to be “an artist”; to write otherwise would be “masturbation or something”; A Whistle in the Dark, being about “the violence of the bloodknot”, was rejected by Blythe who disbelieved that the Carneys exists; The Orphans (1968) “an awful shit of a play, a terrible play”. Murphy still believes The Blue Macushla (1980) to be a good play; gave up writing in 1976 for two years and three months after The J. Arthur Maginnis Story [1976] and The Sanctuary Lamp; bought period house in Rathfarnham with 17 acres; returned with Epitaph under Ether (1979), a compilation from Synge; of theatre, he says, “in the evolution of drama, actors came first” and that he is “providing the score”, “the theory”; Murphy discusses a recent cover-article on Irish artists in Newsweek which poses the question, ‘If Irish artists thrive on misery how are they doing in Boom Times?’, and wonders why no young playwright has tackled the question, “erious money at what cost?”; “People can count their earnings in millions but I think they are still longing. Even if they are racing so fast there is some degree of numbness of the skull, ideas of being alive are still mysterious.” Find Beckett’s plays “very difficult to clue into” but admires the prose; working on adaptation of Chekov’s The Cherry Tree.

Michael Billington, ‘An Irish fox waiting to be caught abroad’, in Guardian Weekly (25-31 Oct. 2001) [“Theatre”]: article based in interview at the Abbey during Murphy revival (Oct. 2001). Billington quotes Kenneth Tynan on Whistle: ‘arguably the most uninhibited display of brutality that the London theatre has every witness’; on the Carney family in Whistle, Billington writes, ‘Murphy told me that the play sprang from his knowledge of migratory Irish workers, their sense of betrayal by their homeland and the violence that often surrounded them.’ Billington frankly remarks of Bailegangaire: ‘I am not clear if it is about familial renewal or about Ireland’s need to escape from its own historic myths. Perhaps both. But it haunts the imagination. it also proves yet again that Murphy ... has left his fingerprints on posterity: McDonagh’s The Beauty Queen of Leenane was clearly influenced by its imagine of domestic domination and subservience.’ Billington regards it as paradoxical that ‘one of the Irish theatre’s proudest possessions is also one of its least-known exports’. The article-title is based on Isiaih Berlin’s essay, “The Hedgehog and the Fox”, based in turn on Archilochus’s say, ‘the fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing’.

Eleanor Margolies, ‘Violent Measures’, review of Tom Murphy, Conversations from a Homecoming (Gaiety Th., Dublin) and Marina Carr, Ariel (Abbey Th., Dublin), in Times Literary Supplement (8 Nov. 2002): Conversations on a Homecoming takes place in JJ’s pub - the publican a little like J. F. Kennedy - in the early 1970s, ten years after J. J. has called upon a group of young people to renovate his bar, telling it could become a “wellspring of hope and aspiration” in their East Galway town. The cast include Peggy, who takes singing lessons, Tom (Adrian Dunbar) who writes poetry and speeches, Michael (Conleth Hill) who goes to America as a would-be actor. Returning for the homecoming of the title, he joins the oters in stripping strip each other bare exposing J. J. as “dangerous slob”. Margolies remarks: ‘Murphy’s seamless exploration of disillusionment [...] has a surprising relevance now in Ireland, during the re-examination of what was achieved and destroyed during the boom of the “Celtic Tiger”. (TLS, p.2.)

[ top ]

Nicholas Grene, ‘Tom Murphy and the children of loss’, in The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Irish Drama, ed. Shaun Richards (Cambridge UP 2004), pp.204-17 [opens with account of staging of The Famine in the Peacock Th., in 1968]: ‘A different dimension to the post-Famine deformations of Irish society was dramatized in Murphy’s first full-length play A Whistle in the Dark. This, the play which made his name in 1961 with a spectacularly successful London production, brought to the stage the culture of violence by which a family of Irish emigrants in Coventry attempted to give heroic meaning to their denigrated and marginalized lives. In a much more comic key, though a sharply satiric one, was the play written in the early 1960s but produced at the Abbey theatre only in 1969, A Crucial Week in the Life of a Grocer’s Assistant. The progress of the grocer’s assistant, John Joe, through his “crucial week’; reveals the moral nullity of the small-town life which drives him to leave and dooms him to stay. Famine enacted Ireland’s most terrible tragedy; many of Murphy’s other plays dramatize the smaller tragedies, the tragi-comedies, the dramas of the grotesque which flow from famine for the children of loss. / That is one way of seeing Murphy’s theatre, or rather a way of seeing one side to Murphy’s theatre - historically grounded, precise in social observation, telling the truths of Ireland’s experience of the present and of the past. But take another play of his, performed just three years after Famine at the Abbey. The Morning After Optimism has no specific setting, merely a fairy-tale forest. It has just four characters, two couples set in formal opposition one to the other: James, a vicious and neurotic pimp, and Rosie his ‘dated whore’; Edmund, a poetical idealist in Robin Hood costume, and Anastasia the maiden of his dreams. Each character has an idiosyncratic language of his or her own. James and Rosie speak a worn-down slang of the urban [205] underworld; Edmund and Anastasia express themselves in various forms of high-flown rhetoric. We are never allowed to know why James is in flight from Edmund, or whether Edmund is really his brother or his half-brother, as the story has it that Edmund was fathered by a king in a casual encounter with James’s mother. Is it significant that Edmund, the ‘good’ brother, bears the name of the ‘bad’ bastard brother from King Lear ? Murphy deliber- ately refuses to offer answers to such questions, just as he deliberately cuts the moorings of this dramatic situation from any ‘real’ world outside the theatre.’ (p.205-06.)

Nicholas Grene, ‘Tom Murphy and the children of loss’, in Cambridge Companion, ed. Richards, Cambridge UP 2004) cont. [on Bailegangaire]: ‘Unlike The Gigli Concert, Bailegangaire is specifically and explicitly concerned with Ireland and Irish experience. What is more, its setting represents a return for Murphy to a subject he had chosen to avoid at the outset of his career. The one thing on which he and Noel O’Donoghue had agreed, when planning to write what became On the Outside, was that it was not going to be set in a kitchen (Tom Murphy, 22). The-country-cottage kitchen, by the 1950s, had become synonymous with the stereotypical ruralism of the traditional Abbey Theatre play. Much of Murphy’s theatrical experimentalism, through the 1960s and 1970s, had been a search for new forms and styles to replace such conservative representationalism. There was a self-consciousness, therefore, in his choice of time and place for the action of Bailegangaire: “1984, the kitchen of a thatched house” (Plays: Two, 90). Bailegangaire uses its old-fashioned, even archaic, setting in a contemporary period (for its original 1980s audience) to create a view of the relationship between past and present in Ireland.

Old Ireland is represented by Mommo, the senile grandmother sitting up in the double-bed which dominates the stage. Mary and Dolly, the two grown-up granddaughters who care for her, stand for the Ireland of the 1980s. From outside the cottage we hear news of the Japanese-owned computer plant down the road. Dolly’s house and lifestyle, as she de- scribes it ironically, reflect a relatively prosperous, modernized society. “I’ve [214] rubber-backed lino in all the bedrooms now, the Honda is going like a bomb and the lounge, my dear, is carpeted” (Plays: Two, 107). Dolly and her children are supported by the weekly remittances of her husband working in England. Just how dysfunctional this family arrangement is, however, is re- vealed in Dolly’s account of his annual returns for the Christmas holidays, when he beats her up in revenge for her infidelity. At the time of the play’s ac- tion she is facing a crisis because she is pregnant, an all-too-evident proof of her unfaithfulness. The older, unmarried sister, Mary, though she succeeded in leaving home and having a successful career as a nurse in England, hardly has a happier life. Having returned in search of some sort of emotional ful- filment, she now finds herself trapped in the role of permanent carer for a grandmother who will not acknowledge her identity, but treats her as an intrusive servant.

The constant accompaniment to the lives of these 1980s women is Mommo’s storytelling. Her senile dementia takes the form of repeating always the one story without ever being able to finish it. The story is that of a laughing-contest, a competition between two men as to who could laugh longest, which happened years ago, with disastrous consequences: one of them literally laughed himself to death, the other died shortly after. Mommo tells this as a traditional folkstory, in the style of a formal shanachie. What she never admits is that she herself was involved; her husband Seamus was the ‘Stranger’ who challenged Costello, the champion laugher of Bochtan village, and it was she, the Stranger’s wife, who egged him on, supplying the subject for their laughter: ‘misfortunes’. The full dimensions of the tragedy only emerge in the course of the play. While the laughing-contest continued in the distant Bochtan pub, the young orphaned grandchildren (including Dolly and Mary) were left untended, and their brother Tom died in an accident as a result. It is because Mommo cannot face these consequences, because she has never been able to work through the trauma of these events, that she is unable to finish her story or own up to it as hers.

The experience produced by the split drama of past and present narratives in Bailegangaire is one of the richest and most resonant in modern Irish theatre. Mommo’s storytelling is compelling, hypnotic, given out in a highly wrought rhythmic style, combining Irish-English dialect with showy Latinate vocabulary:“It was a bad year for the crops, a good one for mushrooms, and the contrary /

and adverse connection between these two is always the case” (Plays: Two, 94).Even for an audience which finds such a style initially hard to understand, there is a delight in the elaboration of the language, the virtuoso skills of the performer acting out all the parts in the story. (The part of Mommo was [215] created by the great Irish actress Siobhan McKenna, in a magnificent last stage appearance.) At the same time the simple dynamic of suspense makes us want to reach the end of the story. We feel thus with Mary, who in the course of the action decides to urge her grandmother on at last to complete the narrative. This she finally achieves. The ending is one of renewal and reconciliation of the sundered and traumatized family, as the story is told to its end, Mommo finally greets Mary by name, and Mary agrees to accept Dolly’s still-to-be born baby as her own.

Though Bailegangaire is without overt allegorical design, it is hard to see the figure of Mommo without thinking of Cathleen ni Houlihan, Ireland personified as an old woman to be rejuvenated by the sacrifice of her young male patriots. It was an image made famous by W. B. Yeats’s and Lady Gregory’s 1902 play Cathleen ni Houlihan. For Mommo, however, there will be no miraculous rejuvenation; she is a convincingly real old woman at the end of a long life. In so far as there are associations with Cathleen ni Houlihan, it makes for a sardonic comment on the figure: Ireland as a senile old crone unable to forget her past, unable to come to the end of her story. The subject of the laughing-contest is also suggestive of Irish traditions of black comedy as a means of exorcising the memories of deprivation. The frenzied laughter of the contestants and spectators at the laughing-contest turned the village of Bochtan (meaning “the poor man’;) into Bailegangaire, the “town without laughter’, where adults never laughed again. Yet Bailegangaire works as a theatrical means of living through such memo- ries, and coming to terms with them in the present. And that process is not merely a therapeutic strategy for bringing into consciousness the blocked-out terrors of the past. Storytelling as a skill, an art, in all its energy and brio, is as full-throated a means to expressive transcendence as the arias of Gigli.’ (p.216; a full copy of the Companion to 20th c Irish Drama at Archive.org online; accessed 02.04.2021.)

Heinz Kosok, ‘The Easter Rising versus the Battle of the Somme: Irish Plays about the First World War as Documents of the Post-colonial Condition’, in Irish Studies in Brazil, ed. Munira H. Mutran & Laura P. Z. Izarra (Sao Paolo: Associação Editorial Humanitas 2005): ‘[Tom] Murphy’s The Patriot Game [1991] proved that even in the Nineties there was an audience in Ireland ready to underwrite the type of hero-worship [of the 1916 leaders] that O’Casey, some sixty years before, had set out to debunk. Murphy’s somewhat anachronistic approach can perhaps be explained by the fact that the play had its origins in a much earlier television script of 1966. By 1991, he argued that “the danger in the Irish Republic was as much one of ‘repressing’ the Rising from national memory as of glorifying it into a national illusion.’ ([Quoted in] Fintan O’Toole, Tom Murphy: The Politics of Magic, rev. edn. Dublin: New Island Books; London: Dick Hern Books 1994, p.151; here p.98; The Patriot Game listed in bibl. as 1991 [ibid., p.101].)

[ top ]

Sara Keating, ‘An intimate portrait of power’, review of The Last Days of a Reluctant Tyrant, by Tom Murphy, in The Irish Times (30 May 2009), Weekend, p.8: ‘[...] Grand epic sweeps at society aside, The Last Day of a Reluctant Tyrant is also an intimate family play, as poignant a portrait of a family crisis as his 2000 play The House, or the savage 1963 tragedy A Whistle in the Dark. The matriarch, Arina, is the tyrant of the title. Once a lowly peasant girl, she married in degenerate, decaying aristocratic family and literally saved it from ruin. Now she is a bitter old woman, vying for power with her senile husband and contemptible sons. / Like King Lear, she must divide her kingdom, and like Lear, she must choose between her three children; in this case sons, each more reprobate than the next. As they disown her and leave her to fend for self, she must come to terms with the legacy of all her hard work and uncompromising living: the absolute corruption of her sons. There is the slovenly Stephen who drinks himself to death; the apathetic Paul, who literally gives up on life; and the despicable Peter, a masterpiece portrait of hypocrisy, who thrives on the misfortune and ruin of his brothers. [...] The Last Days of a Reluctant Tyrant follows her [Arina’s] fate to its bitter, impoverished end. Haunted by the ghosts of those she sacrificed for industry and wealth, she is left to account for herself. Like Dada in Murphy’s A Whistle in the Dark, who sees his sons turn on him as he has forced them to turn on each other, she is left to deal with the legacy of her own life: the sheer weight of its spiritual wastage. / But a tyrant can’t be wrong, in her own eyes at least: tyranny is defined by dogged self-belief. And so Arina will leave this world unrepentant and take whatever punishment is due in the life hereafter. She will not enforce her own claim on salvation, she says in the play’s closing lines, and yet Murphy still suggests that she might get it. There may be no comfort for her in this bleak, bleak world, but Murphy still believes in the possibility of her forgiveness in the next.’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

Sara Keating, ‘A Sort of a Homecoming’, in The Irish Times (5 May 2012), Weekend, p.7. ‘Murphy came from a family of emigrants, with a lot of older brothers. He was the only one to avoid the fate of his generation, who were fleeing the economically and culturally depressed landscape of the 1950s in their thousands and seeking work abroad. But the success of A Whistle in the Dark inspired him to leave his secure teaching job in his hometown of Tuam, in Co Galway, and move to London to become a full-time playwright. Murphy wrote his next two plays amid the chaos of a city at the centre of the political and sexual revolution, but he continued to reflect the anxieties of the country he had left behind. By the time those plays were ready for production, the Abbey had entered a new era under the directorship of Tomás MacAnna, who staged the ambitious Brechtian drama Famine and the equally complex dream-play A Crucial Week in the Life of a Grocer’s Assistant in 1968 and 1969. Murphy moved back to Ireland soon after. [...] Murphy’s plays present a brooding vision of Ireland that is far from the nostalgic rural Utopia of the emigrant’s dreams. Family values are suberted by violence and dysfunction, Catholicism is “a poxy con”, and society is split divisively between the haves and have-nots, failing its young spectacularly. For Murphy’s disenfranchised characters, Ireland is like “a huge tank. And we’re at the bottom, splashing around all week in their Friday night vomit, clawing at the sides all around.” It is an uncompromising, often unpalatable vision far from the simplistic international stereotypes of the Emerald Isle. [...] (For full text version, see RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index or direct.)

Patrick Lonergan, at the Abbey Theatre Blogspot (24 Jan. 2011): ‘[...] Tom Murphy’s Last Days of A Reluctant Tyrant at the Abbey took on our two biggest problems: the obsession with property, and the way in which the Catholic church carried out, and colluded in, the abuse of the most vulnerable. Its central character Arina had “old her soul’, we’re told. “Property, land, money. That’s all she ever thought of’, says her son – placing Last Days in the context of the growing number of Irish productions that present the Celtic Tiger years in terms of a Faustian pact (The Seafarer, Druid’s The Gigli Concert, Terminus, Freefall, and others). I thought there was some marvellous acting in Conall Morrison’s production. Declan Conlon and Frank McCusker should certainly be forgiven if they feel disappointed not to have been nominated [for Abbey awards]. So should Murphy himself: the play may have been flawed, but an imperfect Murphy play (aren’t all of his plays somewhat imperfect when first produced?) is still far better than a lot of other work.’

Colm Tóibín, ‘Tom Murphy’ [interview with Tom Murphy], in Bomb, 120 [“The Artist’s Voice since 1981” - spec. iss.] (Summer 2012) - Murphy, speaking of The Morning After Optimism: ‘[...] Once upon a time there was a boy as there was always and as there always will be, and he was given a dream, his life. His mother told him, “Do not be naughty, nobody’s naughty.” And there would be a lovely girl for him someday, and she would have blue eyes and golden hair. His father taught him honesty, to stand direct and be sincere - like every other person in the world. And on the stroke of 12 on his 21st birthday, he would become a man, and he would not be afraid to have his appendix out. And the teachers and the church told him that there was a devil but he wasn’t alive, really. And the kindest stork with a great red beak would take care of any works and pomps. Everyone was made like God, even the little boy himself. / The balloons that were given to us - and I was gullible, obviously, maybe more gullible than most, and more pious than most - the balloons lifted me above the ground so that I didn’t have to walk a step anywhere. Until one of them burst. And one beautiful balloon after another burst. Illusions that are fed by the church, fairy tales that you believe, and maybe I was a slow developer, but ... why did I start with that?’ (Available online; see full version in RICORSO, Reviews, as attached.)

Belinda McKeon, interview with Tom Murphy, in The Paris Review (9 July. 2012): ‘Tom Murphy is Ireland’s greatest living dramatist. We say things like that in Ireland—Ireland’s greatest this, Ireland’s greatest that—as though it means anything in the greater scheme of things. Who cares what Ireland thinks is great? Tom Murphy doesn ‘t. But it’s true of him, that accolade, I promise you. There’s nobody like him writing today. Various theories exist as to why his work is not as well-known in the United States as it ought to be; most of those theories touch on the emotional intransigence of his work, on its refusal to offer release through moments of redemption, conciliation, or through that thing you might have heard about when it comes to Ireland: that business of craic. Now, these theories are being tested, as three of Murphy’s greatest plays are playing at the Lincoln Center Festival, in a production by Ireland’s renowned Druid Theatre Company, the company best known in the U.S. for its work with the plays of J. M. Synge, Martin McDonagh, and Enda Walsh. / Although in conversation Murphy, now seventy-seven, is more mellow than his plays suggest he might be, the watchfulness is still the same; that dark intelligence has gone nowhere. [...]’ (For interview in full, see attached.)

[ top ]

Fintan O’Toole, ‘An Irish Genius in New York’, review of the DruidMurphy production of plays by Tom Murphy at Lincoln Centre Fest. in John Jay College, NY, July 2012, in The New York Review of Books (16 Auyg. 2012): ‘Tom Murphy’s body of work is as rich and potent as that of any living playwright, but it began with a rather desultory conversation. On a Sunday morning in 1959, in the market square of the small West of Ireland town of Tuam, Murphy and his friend Noel O’Donoghue leaned against a wall, waiting for the pubs to open. “Why,” asked O’Donoghue out of the blue, “don’t we write a play?” It was not as odd a question then as it might now seem, for, as Murphy later recalled, “everyone in the country in 1959 was writing a play.” What, Murphy asked, would they write about? “One thing is sure,” O’Donoghue replied. “It’s not going to be set in a kitchen.” [Recounted by Murphy in Intro. to On the Outside/On the Inside (Gallery 1976).] / This declaration of intent was not just a matter of physical setting. The kitchen had come to symbolize the social and imaginative limits of Irish theater. Brendan Behan remarked that the actors at the national theater, the Abbey, must constitute the best-fed group of players in Europe because, at the moment of crisis in the domestic comedies that had become their staple fare, someone would inevitably say, “Musha, will ye be putting on a pan of rashers.” But as the thrilling DruidMurphy cycle makes clear, Murphy has no interest in the kind of play where a crisis is resolved by putting on a pan of rashers. A Murphy drama may sometimes look small on the surface - some of his most daring pieces are three-handers—but his work is always vast. Big, wild forces of history, myth, and deep psychology howl in the wings and constantly threaten to overwhelm the apparent order of the stage.’ (See full text at NYRB - online; accessed 12.11.2012 [password required].)

Fintan O’Toole, review of Nicholas Grene, ‘The Theatre of Tom Murphy, in The Irish Times (17 Feb. 2018) |

Next year, it will be 60 years since Tom Murphy and his friend Noel O’Donoghue, waiting in the square in Tuam for the pubs to open on a Sunday morning, decided to write a play. They submitted On the Outside, an astonishingly accomplished enactment of youthful rage, to the one-act play competition at the All-Ireland amateur drama festival in Athlone, where it won first prize of 15 guineas. As Nicholas Grene reminds us in his splendid overview of Murphy’s 20 original plays and seven stage adaptations, On the Outside was submitted under a pseudonym: Aeschylus. In 1961 Murphy submitted his first full-length play, The Iron Men, to Athlone under another pseudonym, Dionysus. There is, of course, a glorious kind of cheek in a Tuam sham adopting the names of one of the great founders of western drama and of the Greek god under whose aegis the original theatre festivals were organised. But in retrospect these gestures seem to derive from something deeper than youthful impudence. Aeschylus’s work is severe, pure, almost ascetic in its form. Dionysus, on the other hand, is the god of wine and fertility and of ritual madness. The two pseudonyms are comic nods in different directions - on the one side, toward a kind of dramatic stringency and, on the other, toward the wild and dark impulses that drive us beyond the edge of reason. This doubleness foreshadows the unique nature of Murphy’s achievement, his highly distinctive combination of classical form and romantic content, his ability both to let the dark forces loose and to contain them aesthetically. Murphy’s career is not easy to write about as a whole, not just because of its extraordinary length but because of its remarkable breadth. His great Irish contemporary and admirer Brian Friel provides a useful point of contrast. Friel is an excavator, returning again and again to the same patch of ground, the same obsessions and mysteries, and digging ever deeper into them. But Murphy is an explorer. He ranges restlessly across the universe. Almost everything you might want to say about him is equally true. He can be seen as a ferocious social realist in work like A Whistle in the Dark (which The Iron Men became) or Conversations on a Homecoming; as a fabulist in The Morning After Optimism and Bailegangaire; as a mythmaker in The Sanctuary Lamp and The Gigli Concert. Fusion of forms And yet, the real point of Murphy’s career is not even this tendency to shift forms from play to play. It is, rather, the fusion of forms within the plays. It is no good for the critic to merely sort his plays by type - the metaphysical over here, the social over there, the brutality in this stream, the dreams in that one. At his very best - a state he achieves with a regularity rare in this most unsteady of artistic professions - Murphy’s plays are not either/or but both/and. They are richly layered. The Gigli Concert, for example, is highly political: the Irishman is a stunning embodiment of a figure that haunts not just Irish dreams but Irish nightmares - the property developer. But it is also the most ambitious, daring and successful version of that core myth of European modernity, the tale of Faust. It is, meanwhile, both highly contained and mind-blowingly wild - Aeschylus at the service of Dionysus. And the same is true of so many plays: Murphy’s leaps into the great beyond are from solid and carefully mapped social ground, and his social realism is never inclined to forget that human reality includes fantasy, aspiration and an implacable yearning for the impossible. Internal dynamism Murphy is a great playwright and we have been fortunate to be (to borrow a phrase from The Gigli Concert) “alive in time at the same time” as his daring imagination has found its varied embodiments on the stage. This book is not, and does not want to be, the last word on an achievement that has yet to be fully fathomed. But it is the best and most complete that anyone has yet produced and all future scholars and critics will use it is as the diving board from which to plunge into Murphy’s deep and turbulent waters. |

| Available online; accessed 16 May 2018.

|

[ top ]

Peter Crawley, ‘Tom Murphy’s new play draws on the source of all his storytelling’, in The Irish Times (6 Sept. 32014), Weekend: ‘[...] In the early 1970s Murphy was contacted by Frank J Hugh O’Donnell, a critic and playwright who had worked in Murphy’s native Tuam. “He was a charming old man,” Murphy says in the elegant living room of his Dublin home, amid stacks of books. “He told me the story of a man, a stranger, who comes into a pub in Milltown one night where he heard a particular laugh. As usual in a company, there’s somebody with a particular laugh that is infectious. And he said, “I’m a better laugher than him,’ ” Murphy says, laughing. “It was wonderful. I stored it for 10 or 12 years, and I had to make up why he threw out the challenge and what could make them laugh all evening ... I arrived at “The Misfortunes.’” / For a long time this story was just a tale to tell his children. It has now inspired three works by Murphy. In the same year that Bailegangaire premiered, the Abbey staged its companion piece, A Thief of a Christmas, the dramatisation of the laughter competition that Murphy contentedly remembers as “possibly one of the worst plays”. / Before either of them, though, Murphy had written a script for a television play about Mommo and her sculptor husband, Seamus. Set in the 1950s, Brigit was broadcast by RTÉ in 1987. Last year Murphy returned to the piece and rewrote it entirely for the theatre. It will now be staged by Druid, in a production directed by Garry Hynes, and performed alongside a revival, featuring Marie Mullen, of Bailegangaire.’

Further: ‘The story of making an artwork for the church had come from the experience of a friend, the late painter Tony O’Malley, who once furnished a parish with a statue. But it chimed with another tale that Murphy, the youngest of 10 children, had learned from his eldest brother. “He told me a story about my father, who had done work for the church, and the church short-changed him.” In retaliation Jack Murphy boycotted Mass, and his son laughs delightedly at the story of the protest, almost a signature combination of spirituality and economics. [... &c.]’

also quotes Murphy: “I don’t have an academic mind [...] Writing a play is not an intellectual process. I’m not sure what it is. But you have to have tenacity and concentration and discipline, and all these things will be rewarded. When I come to write a new play I wonder how I wrote the last play.” (Available online.)

Fintan O’Toole - Obituary notice in The Irish Times (16 May 2018) When Tom Murphy and his friend Noel O’Donoghue stood in the main square in Tuam, Co Galway on a Sunday morning in 1959, they decided to write a play. ”What will it be about?”, O’Donoghue asked. ”I don’t know”, said Murphy, ”but it won’t be set in a kitchen.” The remarkably accomplished one-act play they created was called On the Outside. It was not set in a kitchen. And it inaugurated one of the greatest playwriting careers of the last 60 years.

Murphy, who died on Tuesday night at the age of 83, didn’t do kitchen-sink drama and he was always a little bit on the outside. But he produced play after play marked by soaring imagination, ferocious honesty, great artistic ambition and unshakable integrity. Irish theatre, at first, had no place for him. His first full-length play, A Whistle in the Dark, set among Irish exiles in Coventry, was angrily rejected by the Abbey. When it was produced by Joan Littlewood at her pioneering Stratford East theatre in London in 1961, it made an enormous impact because of its emotional ferocity and disturbing air of violence. In retrospect, however, it is not a work of kitchen-sink realism but one of the few successful classical tragedies written for the modern stage. For what made Murphy such a distinctive, original and restless presence in the theatre of the last six decades was his ability to evade easy categorization, to bring together the intense exploration of private anguish and the epic treatment of history, politics and myth.

On the one hand, Murphy’s great body of work can be seen as an inner history of modern Ireland. The legacy of famine and mass emigration haunts his plays, from A Whistle in the Dark, to Famine to Conversations on a Homecoming to The House and The Wake. He gives us a world of broken, displaced people, a culture that cannot cohere. His characters often feel like they are one half of a lost whole. The historical sweep in Murphy’s body of work takes us from the 1840s all the way to Ireland’s ambivalent process of globalisation and Americanisation. But it is never about generalities. Murphy always kept his faith in the stage as an arena where human emotions are tested and the inner workings of the personality are given a local habitation and a name.

On the other hand, Murphy, from Tuam, Co Galway, was much more than an Irish playwright. Like all great dramatists, he was in constant dialogue with the history of the form. His brilliantly imaginative The Gigli Concert, for example, is both the best modern transformation of the Faust myth for the stage and a bold venturing into the terrain where theatre overlaps with opera. (It is also, like so much of his work, wildly funny.) The Sanctuary Lamp, set among down-at-heel circus performers, occupies a strangely resonant space between Catholic imagery and The Oresteia Greek tragedies. The Morning After Optimism is a darkly hilarious journey into the words of fairy tale and Jungian archetypes. Above all, Murphy was always in dialogue with the Greeks, seeking ways both to give their tragic vision its due and, somehow, to reach beyond it into the possibility of an unsentimental hope.

The scale of this theatrical ambition has been sustained by an extraordinary mastery of language on stage. The literary play may be under pressure as a form in the 21st century, but Murphy sustained it superbly and new generations will surely go back to him. As one of his characters in The Gigli Concert put it, he had a delicate ear - an ear for the troubles, confusions, hurts and hopes hidden in our voices and turns of phrase. His approach to characters was primarily through the sounds they make. Words are woven into intricate duets and trios and ultimately into soaring verbal arias like those of Mommo in his masterpiece Bailegangaire where language becomes a mesmerizing force in itself.

Generations of actors found they could both sink into and find themselves buoyed up and carried along by Murphy’s rich, bold, daring and musical words. Generations more will surely make the same discovery.

[ top ]

Quotations

On the Irish Famine: ‘The absence of food, the cause of famine, is only one aspect of famine. What about the other “poverties” that attend famine? A hungry and demoralised people becomes silent. People emigrate in great numbers and leave spaces that cannot be filled [...] The dream of food can become a reality - as it did in the Irish experience - and people’s bodies are nourished back to health. What can similarly restore mentalities that have become distorted, spirits that have become mean and broken?" (Plays: One, xi; quoted in Nicholas Grene "Tom Murphy and the children of loss", in Shaun Richards, Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Irish Drama (Cambridge 2004, [Chap. 15] p.205; The Companion is partially available at Amazon Books - online; accessed 26.04.2021.)

[Note that the phrase, ‘A hungry and demoralised people becomes silent’, was quoted at the head of Mary Robinson’s 1995 speech ‘Why should we commemorate the Famine?’ given in Sydney in 1995. See copy of the address given [also] in Chicago - as infra.)

Further: ‘How the natural extravagance of youth, young manhood, young womanhood was repressed, while the people preaching messages of meekness, obedience, self-control I observed had mouths that were bitter and twisted. And I began to feel that perhaps the idea of food, the absence of food, is only one element of famine: that all of those other poverties attend famine, that people become silent and secretive, intelligence becomes cunning. I felt that the hangover of the 19th century famine was still there in my time; I felt that the Irish mentality had become twisted.’ (Interview, quoted in Nicholas Grene, ‘Tom Murphy: famine and dearth.” in Hungry Words: Images of Famine in the Irish Canon, ed. George Cusack & Sarah Goss (Dublin: IAP 2006), pp.245-62; pp.255-56; quoted in Barbara A. Pitrone, ‘Emerging Imagery: Great Famine in Nineteenth Century Irish Lit.’ [MA Diss.] (Cleveland State U. 2016), p.111.)

[ top ]

References

Grattan Freyer, Modern Irish Writing (1979), incls. On the Outside [one-act play set outside a dancehall].

Peter Fallon & Seán Golden, eds., Sof t Day: A Miscellany of contemporary Irish Writing (Notre Dame/Wolfhound 1980), From A Crucial Week in the Life of a Grocer’s Assistant.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3, selects Bailegangaire [1236-65]; BIOG & COMM, 1307 [as above].

[ top ]

Notes

Bailegangaire (1): first performed 1985; Mommo tells over and over again a story she never finishes. It relates how the town of Bochtán came to be known as Baileganagaire, the town without laughter. Her granddaughter Mary ministers to her side, while dreaming of leaving forever, and Dolly counts down the days before her husband returns from England, determined, this time, to be ready for him. [Abbey notice associated with production of Brigit and Bailegangaire, Olympia Th., 1-5 Oct. 2014; produced by Druid during the Dublin Arts Festival of 2014.]

Bailegangaire (1): Siobhán McKenna created the role of Mommo; Tom Hickey and Godrey Quigley resp. played in the part of J. P. W. King and the Irish Man in the first production of The Gigli Concert; Seán McGinley played Harry in A Whistle in the Dark and John Kavanagh as Francisco in The Sanctuary Lamp on their first outings. During the 2001 revival, Pauline Flanagan played Mommo, Jane Brennan played Mary and Derbhle Crotty played Dolly in Bailegangaire, dir. Tom Murphy; Mark Lambert played J. P. W. King, Owen Roe played the Irish Man and Catherine Walsh played Mona on The Gigli Concert, dir. Ben Barnes; Declan Conlon played Michael, Clive Geraghty played Dada and Don Wycherley played Harry on A Whistle in the Dark, dir. Conall Morrison; Stephen Brennan played Harry, Frank McCusker played Francisco, Sarah-Jane Drummey played Maudie and James Greene played the Monsignor in The Sanctuary Lamp (dir. Lynne Parker); Mikel Murfi played James, Masmine Russell played Rosie, Laura Murphy played Anastasia and Alan Leech played Edmund in Morning After Optimism (dir. Gerry Stembridge). Bailegnagaire, by Tom Murphy (1985) toured by the Steeple Theatre Company, dir. Gerry Barnes [at Riverside Theatre, Coleraine, 1990]. [ top ]

Bailegangaire (3): Programme notes state that his earliest theatre venture was a collaboration with Noel O’Donoghue, On the Outside (1959), which received amateur production in Cork and a RTÉ broadcast in 1962; made his first major impact with Whistle in the Dark, Theatre Royal, Stratford East, London, and transferred to West End; for Kenneth Tynan it was ‘unarguably the most uninhibited display of violence that the London stage has ever witnessed’; presented in Dublin in 1962, American premiere 1969, and nominated Play of the Year by Time. Besides TV plays, he wrote in London A Crucial Week, &c., first presented at the Abbey in 1969, and Famine, first staged at the Peacock and transferred to the Abbey [see memorial plaque in new Abbey Theatre bar]. Returning to Ireland in 1970 he wrote The Morning After Optimism. In 1974 On the Outside and a companion piece On the Inside appeared at Dublin Theatre Festival. Murphy made a highly successful adaptation of Vicar of Wakefield [n.d.] followed by The Sanctuary Lamp which proved controversial at 1975 Dublin Theatre Festival; defended vigorously by Cearbhail Ó Dálaigh [President of Ireland], as one of the three best plays seen at the Abbey after Juno and the Playboy. The J. Arthur Magennis Story, a ‘romp’. Murphy settled in ‘savannah lands of Rathfarnham and set about taming it’, taking time off from writing; adapted Liam Ó Flaharta’s The Informer for Dublin Theatre Festival in 1980; adapted She Stoops to Conquer to an Irish setting for the Abbey, 1982. The Gigli Concert, finished Christmas Eve 1982 and presented Oct. 1983 at the Abbey in the Dublin Theatre Festival, winning Murphy the Harvey’s and Independent Newspapers awards. Became writer in assoc. with Druid Theatre Company in Sept. 1983, leading to the presentation of four of his plays, Famine in 1984, On the Outside in 1985, and Conversations on a Homecoming also in 1985, originally written as part of The White House in the mid-1970s, it now became hit of the 1985 Dublin Theatre Festival. Bailegangaire, written for Siobhan MacKenna who appeared as the grandmother, Mommo, who tells the story of the laughing competition, opened at the Druid Lane Theatre on Dec. 5th 1985, in London on 19 Feb. 1986, and at the Gaiety Theatre, Dublin on 13 May 1986. A companion piece, A Thief of a Christmas was simultaneously produced at the Abbey. The poem quoted by Mary in the course of Bailegangaire is ‘Silences’ by Thomas Hardy.

The House (2000; Abbey revival 2012): ‘It’s the summertime and the emigrants have returned - cursing, crooning and carousing, they’ve got the backs up of official Ireland, who pray for their souls at Mass each week, while themselves indulging in blackballing and backhanders. Among the Diaspora are Christy ( Conlon ) and Susanne ( Walker ), the “like a son” and actual daughter of Eleanor Methven’s Mrs. DeBurca. She’s upping sticks and moving in with her eldest, Marie (Belton), selling the house she called a home after the death of her husband. Christy’s questionable riches may provide the salvation she craves but his darker nature has a combustive effect on the women of the house so that he eventually destroys the thing he loves. [...]’ (See review by Caoimhin Keane at Entertainment.ie - online.)

Birth-date? Anthony Roche cites Murphy’s birthdate as 1936 in ‘Murphy’s Drama: Tragedy and After’, Contemporary Irish Drama From Beckett to McGuinness (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1995), pp.129-88.

“The Dubliners” & Murphy: In 1976, Tom Murphy wrote The J. Arthur Maginnis Story for the group whose members incl. Luke Kelly (m. to Deirdre O’Connell, founder of the Focus Theatre), Ronnie Drew, et al. The Dubliners performed as actors and musicians in Brendan Behan’s last, unfinished play, Richard’s Cork Leg, in 1972. (See Fintan O’Toole, review of Ronnie Drew’s one-man show, Irish Times, 4 March 2005.)

Pauline Flanagan [interview], ‘Actress for All Seasons’ (Irish Times) (15 June 2002), Weekend, p.4: discusses her lead-role as Mommo in Tom Murphy’s Bailegangáire; notes that she starred in the first Druid production with Olwen Fouéré and Jane Brennan; strong Fianna Fáil background, with both parents serving as Mayors of Sligo; orig. from Fermanagh, driven out by pogroms; attended Ursuline Convent with Joan O’Hara; entered Feis Sligigh with Aileen Harte; palyed with Garryowne Players in summer of 1949 at Bundoran; spent three years with Anew McMaster’s company; her role as Mommo based on memories of Emma Fay, a woman who lived across the street in Sligo and whose laughter ricocheted off the walls: ‘what you have got there is her laughing at this terrible life she had’. M. George Vogel, whom she met while playing Juno in Washington; also played Rima in Dolly West’s Kitchen (Frank McGuinness), winning her the Samuel Beckett Award and the Olivier Award for Best Supporting Actress; also appeared in Marina Carr’s By the Bog of Cats, leading to nominatioin for Irish Times/ESB Best Supporting Actress; parts in Portia Coughlan (Carr); Tarry Flynn (Patrick Kavanagh); The Desert Lullaby (Jennifer Johnston/Lyric); A Life (Hugh Leonard); Outer Circle Award for Grandchild of Kings [by Harold Prince] (Irish Rep. Th.)

The Colgan spat: Murphy engaged in a fight with Gate Theatre director Michael Colgan at Colm Tóibín’s home on Upper Pembroke Street during Tóibín’s 50th birthday in 2005. The exchange broke out shortly after Colgan’s arrival - the two having had over twenty years of bad relations in view of Colgan’s never putting on a play by Murphy at the Gate. Murphy began by insulting Colgan and Colgan responded by describing Murphy as ‘only a provincial playwright’. When Murphy described Colgan as a ‘cunt’ and smashed a plate of curry over his head, the latter, bleeding and without his glasses, punched the former, actually knocking him ou, and then left the room but not the party. The two later shook hands. (See Wikipedia > Colm Toibin - online; accessed 14.02.2021. -

[ top ]