Life

| bapt. John Casey; Gl. “Seán Ó Cathasaigh”; finally Seán O’Casey; b. 30 March 1880 at 85 Upr. Dorset St., Dublin, son of Michael Casey, a Catholic and assistant clerk in Society for Church Missions (paid £5.15.8 p.w.; rate-payer), and Susan, a Protestant (née Archer, d. 1918; the Susan Casside of the Autobiographies), youngest of 13 (eight dying in childhood); brought up in Church of Ireland; moved to 9 Innisfallen Parade, 1882; his father died in 1886, by choked on a raw fish, aetat. 49; Seán experienced sporadic eye-trouble beginning with ulcerated cornea in his left eye at five; received treatment from J. B. Story for trachoma at St. Mark’s Hospital, Lincoln Place (“Open up!”); |

|

|

| his elder brothers joined the Army, while a sister Bella [var. Ella] who married a bugler (Nicholas Benson), became a school-teacher and occas. sheltered Seán in her flat; moved frequently to East-Wall addresses incl. Hawthorn Tce.; family settled in 18 Abercorn Rd., 1897; had early associations with Protestant church of St Barnabas [vide Burnupus in Red Roses for Me], d the Orange Lodge; attended Queen’s Theatre with his br. Archie, watching Boucicault, Shakespeare, and others; played small part in The Shaughran in the Mechanics’ Theatre (Hall) [later site of Abbey]; | ||

| worked in stockroom of hardware store, aged 14; some clerical employment, before becoming manual labourer in late teens, continuing as labourer to 1925 [var. 1926]; employed by Great Northern Railways, 1901-11; reported for work when the company declared a holiday on the coronation day of George V, but refused payment for same; formed friendship with Frank Cahill, CBS teacher of St. Laurence O’Toole’s, and co-fnd. St. Laurence O’Toole Club, Seán becoming the secretary of the Club’s Pipe Band; got involved in ITGWU from its foundation, 4 Jan. 1907;joined Gaelic League - which he spoke of later as his university; campaigned to have Church of Ireland [Anglican Communion] services in Irish; | ||

| wrote amateur play, not produced, c.1911; contrib. Irish Worker, from 1912, and associated with Jim Larkin; Lock-Out Strike commences, 15 Aug. 1913, continuing for seven months; became Secretary of Irish Citizen Army, drawing up its constitution, endorsed March 1914; reputedly recruited Ernest Blythe to the IRB; opposed ICA ties with Irish Volunteers; resigned over motion to compel Countess Markievicz to choose between ICA or Irish Volunteers, 17 July 1914; | ||

did not participate in Easter Rising, 24-29 April, 1916; began writing to order for card-manufacturer, Fergus O’Connor, 1917; death of a sister, Isabella, Jan. 1918; as Seán Ó Cathasaigh issued The Sacrifice of Thomas Ashe (1918), pamph., now rare; publishes Songs of the Wren (1918), also two ‘Laments’ for Ashe; death of Mrs. Casey, Nov. 1918 [var. 1919], her funeral being paid by royalties of The Story of the Irish Citizen Army (1919) - for which he was paid £15 - soon after censored by military authorities; |

||

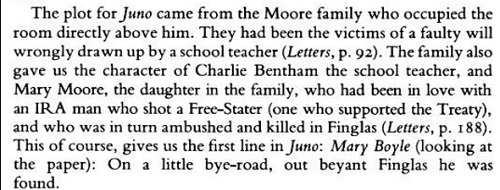

left Abercorn Rd. following violent rows with brothers, and moved in with Mícheál Ó Maoláin at 25 Mountjoy Sq.; raided by authorities on suspicion of Republican activities; moved to 422 N. Circular Rd., where he wrote his so-called “Dublin Trilogy” - as well as Kathleen Listens In and Nannie’s Night Out (1924), for radio; early plays, The Frost in the Flower, written c.1910-12 for drama club of St Lawrence O’Toole Pipers, and based on the experience of one of the teachers who refused a better post offered him out of timidity, submitted to Abbey 1919-20 (not extant); |

||

The Harvest Festival, concerning the beginnings of militancy in a trade union, also rejected by Lennox Robinson; and The Crimson in the Tri-Colour also rejected, though read by Lady Gregory (with a note from Lennox Robinson indicating that it could not be produced at the time for political reasons ‘even if …’); Lady Gregory invites him to visit and advised him to concentrate on ‘characterisation’, his strength; The Shadow of A Gunman (Abbey, 12 Feb. 1923) [var. April, Ayling 1969, ‘three performances at the end of its season’], having been submitted to the management as On the Run; next presented Juno and the Paycock (Abbey, 3 March 1924), set in ‘the living apartment of a two-roomed tenancy of the Boyle family, in a tenement house in Dublin ... 1922ˆ, with Sara Allgood as Mrs. Boyle, F. J. McCormick as Joxer, Mary Boyle; went on to a long run in London (Royalty Th., 16 Nov. 1925), winning the Hawthornden Prize; |

||

presented The Plough and the Stars (Abbey, 8 Feb. 1926), set in a Dublin tenement in 1916, and ded. ‘the the gay laughter of my mother at the gate of the grave’, with Ria Mooney unwittingly cast as the prostitute Rosie, meeting with riotous reception, largely due to characterisation of Pearse as ‘man at the window’, fomented by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington on the fourth night [var third; NYT, 14.11.1976], followed by a public debate with her in the Universities’ Republican Club, in which he was publicly discountenanced, 1926; London premier of The Plough, May 1926; O’Casey travelled to London to receive Hawthornden prize for Juno, late 1926, and never returned to Ireland; greatly helped in London by James B. Fagan who introduced him to critics James Agate and Beverley Nichols and playwright Arthur Pinero; made honourary member of Garrick Club; The Silver Tassie, written in Kensington [Autobiogs.] based on theme in Wilfrid Owen’s poem “Disabled”, rejected by Abbey and more specifically by Yeats; |

||

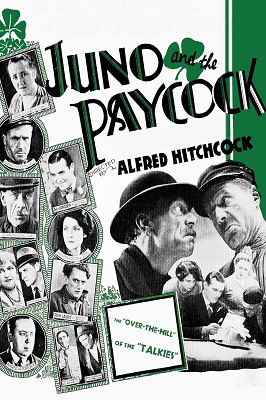

m. Eileen Carey [stage-name; née Reynolds] (b. 27 Dec. 1900, m. 23 Sept. 1927; d. 9 April 1995), who appeared in his plays at the West End; a son Breon, b. 30 April 1928 [d.2011; ed. Dartington College; became artesan jeweller]; visits modern galleries with Eileen in England, and acquires expressionist paintings; engages in acrimonious correspondence concerning rejection of The Silver Tassie by the Abbey, in Irish Statesman, 9 June 1928; a film version of Juno and the Paycock (dir. Hitchcock, 1930) - considered a failure by Hitchcock himself (‘just a photograph of a stage play‘) opening with a speech extolling Irish unity - occasioned riots in Limerick; The Silver Tassie promoted by G. B. Shaw and produced by C. B. Cochran at the Apollo Theatre, London, 11 Oct. 1929, with a set design by Augustus John; ran for 2 months with Charles Laughton in the lead role; O’Casey settled in Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, 1931-35; refused proffered membership of Yeats’s Irish Academy of Letters, 1932; his play Within the Gates, produced London 1934, the last to elicit interest from London theatre managers; visited USA for its New York production, Autumn 1934; clerical opposition aroused at production of The Silver Tassie in Dublin, 12 Aug. 1935; b. Niall, 2nd son, 1935 (d. 1956, of leukemia); |

||

The Plough and the Stars filmed 1936 (dir. John Ford); SOC settled in Devon at Shaw’s suggestion, 1938; wrote The Flying Wasp (1938); issued first volume of Autobiographies as I Knock at the Door (1939); banned in Ireland, followed by Pictures in the Hallway (1942), Drums under the Windows (1945) - the object of hostile review by George Orwell (Observer, 28 Oct. 1945) - Inishfallen, Fare Thee Well (1949), Rose and Crown (1952) and Sunset and Evening Star (1954); b. a dg., Shivaun, 1939; his play The Star Turns Red performed by Unity Theatre, London (12 March, 1940); Red Roses for Me (1942), produced by Shelagh Richards, Olympia Th., Dublin (15 March, 1943), and later in London, (Embassy Th., 26 Feb. 1946); writes Purple Dust (1940), dealing with two Englishmen who buy an Tudor mansion (or ‘big house’) in Ireland; premiered in Liverpool 1945, later enjoying a long off-Broadway run with it in 1956; wrote Oak Leaves and Lavender, a ‘big house’ play set in Cornwall during the Battle of Britain, and dealing with anti-Fascist evangelism, premiered in Hammersmith 1947; |

||

Cock-a-Doodle Dandy (1949) premiered at Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1949, and later successfully produced by George Devine’s English Stage Co. at the Edinburgh Festival, 1959; The Plough and the Stars was revived by the Abbey in 1955, with Edward Golden (Capt. Brennan) and T. P. McKenna (Lieut. Langan), et al.; The Bishop’s Bonfire (Gaiety Th., Dublin, 28 Feb. 1955), produced Cyril Cusack and directed Tyrone Guthrie; The Drums of Father Ned, based events of Tóstal (Nat. Fest.) of 1954, and prepared for the stage at the Gaiety Theatre in the 1958 Dublin Theatre Festival, but withdrawn under pressure when Catholic Archb. John McQuaid refused to permit an inaugural (‘Votive’) Mass for the Th. Festival in view of the inclusion of certain plays, chiefly McCelland’s dramatisation of Ulysses as “Bloomsday” but also mimes and a radio play by Beckett (later produced in Indiana, 1959, and later again at the Olympia Th., Dublin, June 1966, along with O’Casey’s Drums); |

||

reacted against clerical interference by banning professional productions of his plays in Ireland, but rescinded his ban to permit the Abbey to perform Juno and the Paycock and The Plough and the Stars in Dublin prior to appearance at the World Theatre Festival (London 1964); celebrated 80th anniversary, 1960, refusing CBE and honorary degrees; last plays published (1961); O’Casey Festival at Mermaid Theatre, London, Autumn 1962; Belfast production of The Plough and the Stars at Lyric theatre, 1969, and revived successfully in Abbey production, 1976; also directed in Dublin by Joe Dowling, 1993, travelling to London (Garrick Th.), 1995; prose writings collected as Robert Hogan, ed., Feathers from a Green Crow (1962), fugitive writings; Under a Coloured Cap (1963); self-portraits in Donal Davoren in The Shadow of a Gunman (1923), and Ayemonn Breydon in Red Roses for Me (1943); Autobiographies republished in two-volume editions (London, 1963, 1980, 1981, &c.); |

||

d. St Marychurch [sic], Torquay, 18 Sept. 1964, after his second heart attack; Purple Dust was produced by Berliner Ensemble and at Théâtre National Populaire, Paris (both 1966); Young Cassidy (1965) is a biopic with Rod Taylor, Julie Christy, Maggie Smith, and dir. by Jack Cardiff & John Ford; Juno revived (London National Theatre Co. 1966); The Silver Tassie successfully adapted for English National Opera by Mark-Anthony Turnage and librettist Amanda Holden (1997); The Plough and the Stars revived by Ben Barnes (Barbican, London, Jan. 2005); papers are held in the National Library of Ireland; The Silver Tassie was revived by Druid in the Gaiety Theatre, Autumn 2010; The Plough and the Stars was revived in an Abbey Company production at the O’Reilly Theatre, Belvedere, in Dominic St., Dublin, in August 2012 - being the 56th Abbey production of the piece - with

Kelly Campbell and Barry Ward as Nora and Jack

(dir. Wayne Jordan) - touring to Belfat (Opera), Letterkenny, Birmingham, Bath, Tralee, Limerick. NCBE DIB DIW DIH DIL KUN ODQ OCEL FDA OCIL |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bottom Left - Sean with Eileen O"Casey; bottom centre - Sean with Barry Fitzgerald; Bottom Right - Sean with Shivaun O"Casey | ||

[ top ]

WorksChief dramatic works

|

|

| Plays | |

|

|

| Reprint editions | |

|

|

|

|

| [ top ] | |

| Prose | |

|

|

| Autobiography [6 vols.] | |

|

|

|

|

| Miscellaneous | |

|

|

|

[ top ] |

Bibliographical details

P. Ó Cathasaigh [sic], The Story of the Irish Citizen Army (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), 62pp. CONTENTS [i.e., chaps]: The Founding of the Citizen Army; Renaissance; Reorganisation; The Quarrel with the National Volunteers; Pilgrimage to Bodenstown, 1914; The Social Side of the Army; Some General Events; Marking Tim; Some Incidents and Larkin’s Departure; Connolly Assumes Leadership; The Rising; Appendix contains Manifesto, Handbills, and Constitution. [Note that the title page author is given as P. Ó Cathasaigh.] Epigraph to Preface: ‘Answer every man directly, &c’ [four lines of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar] (See extracts in RICORSO Library, “Irish Literary Classics”, infra.)

[ top ]

Criticism| Annual listing |

1971-1980 1980-1989 1990-1999 2000- |

|

|

|

|

|

| [ top ] |

| Film Versions | |

|

|

| Alfred Hitchcock (1930) | John Ford (1936) |

[ top ]

References

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, selects from The Shadow of a Gunman, [677-700], and The Plough and the Stars [700-08]; BIOG & WORKS, 718 [as supra]; FDA3 selects Under the Window, ‘The Bold Fenian Men’ [456-62]; REMS 2 [Dublin speech and the Bible, ed.], 172 [aesthetic hegemony of Abbey in jeopardy [when] O’Casey severed connection; that he did so following the rejection of his First World War play The Silver Tassie with its Expressionist second act, might have intensified a sense that the Abbey had missed the turning tide; the 1930 proved otherwise [with Denis Johston; ed. Terence Brown]; 175 [Dublin plays can be classed tragi-comedy that verge on farce or melodrama; ed. T. Brown]; 247 [nugatory ref. to poem in Time and Tide, in Beckett’s Recent Poetry]; 380 [Easter Rising read by O’Casey and others as ‘bright moments of liberty that have within them darker moments of oppression, radical revelations of the ceaseless discovery and loss of identity and freedom, which is one of the obsessive marks of cultures that have been compelled to inquire into the legitimacy of their own existence … &c’, ed. Seamus Deane]; 382 [O’Casey repudiates 1916 while admiring it, ibid. under ‘Autobiographies and Memoirs’ sect.]; 481 [O’Faolain quotes Yeat’s footlights speech at the Plough Riot, ‘You have rocked the cradle of a new genius’ (sic), in Vive Moi!]; 484 [Patrick Kavanagh, ‘The English critics went crazy over the poetry of O’Casey’s Juno, whereas in fact we only endure that embarrassment for the laughs in Catpain Boyle’, Self-Portrait, 1964, 643 [Denis Donoghue, Yeats, O’Casey [et al.] aggravated by Irish politics to the point where their aggravation turned into verse or prose; ‘We Irish’, in Hibernia, 1978 (1986)]; 656-58 [Dubliners as peasants manqué in early works of O’Casey; Fintan O’Toole, ‘Going West, ‘The Country Versus the City in Irish Writing’, in Crane Bag (1985)], 670 [among Irish masters of modern ‘British drama’, acc. Seán Golden, in ‘Post-Traditional English Literature, A Polemic’, in Crane Bag (1979)]; 940 [part of small writers’ exodus, sect. ed., JW Foster]; 1312 [reconciliation of humdrum fact withpoetry of speech, spoken of by Lennox Robinson in connection with Abbey playwrights, clearly intended for Synge and O’Casey; Kiberd, ed. ‘Contemporary Irish Poetry’ Sect.]; 1313 [his slumdwellers seen to create in rolling speech a kind of spaciousness they can never find in their tenements; ed. Kiberd].

Helena Sheehan, Irish Television Drama, A Society and Its Stories (RTÉ/Mercier 1987), lists The Moon Shines on Kylenamoe, dir. Shelah Richards (1962); The Plough and the Stars, dir. Lelia Doolan, adapt. by Blanaid Irvine (1966), and Do., dir. Michael Garvey (1977); The Shadow of a Gunman, dir. James Plunkett (1966); The Silver Tassie, dir. Brian MacLochlainn (1980); The Rebel [Seán O’Casey], adapt. by John Arden, Margaretta D’Arcy and dir. Brian MacLochlainn (1973); Seán [13 episodes], written by Michael Voysey, Neil Jordan, Eugene McCabe, dir. Louis Lentin (1980).

Kevin Rockett, et al., eds., Cinema and Ireland (London: Routledge 1988), cites Juno and the Paycock (dir Alfred Hitchcock, 1930), film seized and burnt by crowds in Limerick, angered by its portrayal of Irish family life [53]; Further, Plough and the Stars, The (1936), 44, 59, 96, 156-7 [dir John Ford; Jack Clitheroe (Preston Foster); in a curious reversal, it is the family which emerges as fanatics]; 165 [choice between wife and Ireland], 186n17; Young Cassidy (1964 [sic]); John Ford/Jack Cardiff film; ejection of the mob and de-contextualisation of Irish history featured in Young Cassidy 1965 [sic]; very loosely based on O’Casey’s life, the film is so committed to the myth of artistic isolation that the role of politics can only dwindle into insignificance. In order to develop as an artist Johnny Cassidy/Seán O’Casey (Rod Taylor) must abandon ‘everything’, class, political attachments, family, lover, and finally Ireland itself…. the archetypal Fordian loner … [in addition to that archetype] we are [here] denied the virtues of community … the collectivity … possess only a negative value [of the] howling mob in the transport strike [which conditions] his disdain for violence and his disengagement from politics. [Finally] Cassidy relies on police force to remove the mob from the theatre foyer [111, 176-77].

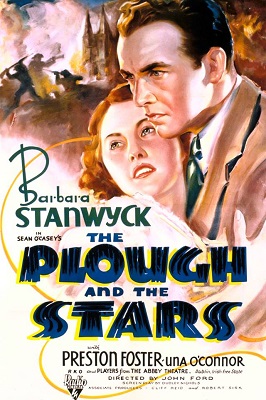

The Plough and the Stars was made by John Ford in 1936 with Barbara Stanwyck cast as Nora Clitheroe and Barry Fitzgerald as Fluther Good; broadcast on on Talking Pictures at 11:15, 7 Aug. 2018. (Eunice Yeates on Facebook, 07.08.1018.) Preston Foster and Una O’Connor. [see poster.]

Booksellers: Autobiographies, 2 vols. (London: Macmillan 1981), 1st combined edn.; R G. Lowery and R Angelin, eds., My Very Dear Seán, George Nathan to Seán O’Casey, letters and articles (Assoc. UP 1985); also P O’Cathasaigh, The Story of the Irish Citizen Army (1st ed 1919) [in seldom found white wrapper]; Autobiographical sextet [all 1st eds.], £120; Pictures (NY 1949); Inishfallen (NY 1949); and Sunset & Evening Star (NY 1st ed. 1954) [Eric Stevens 1992]. Oak Leaves and Lavender (US 1st edn. 1947) [Hyland 1995]. Seán Ó Cathasaigh, The Sacrifice of Thomas Ashe (Dublin: Fergus O’Connor 1918), 16pp. [TCD].

[ top ]

Notes

Plays

Juno and the Paycock: Andrew F Sullivan of the American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic (Hartford, Connecticut, USA), writes to President de Valera on 1 Nov. 1934 to express his feeling that the content of some of the Abbey’s productions while on tour in America portray Ireland in an unfavourable manner: ‘We wish especially to draw attention to one of these dramas Juno and the Paycock […] it was not very edifying, was not Irish, and left a very bad impression of Ireland’. He recommends that the company should only present real ‘Irish Folk Plays which was the purpose originally intended for the founding of the Abbey Players by Lady Gregory and the other founders’. (National Archives, Record 14897 from Department of the Taoiseach; online at 24 Jan. 2008.)

Juno and the Paycock: Louis Laguerre’s “Juno and the Paycock” ( c.1692) is introduced into plasterwork by James Pettifer (1675) below the upper flight of the great staircase at Sudbury Hall, Derbyshire. (See National Trust Engagement Diary, 1992.)

Juno and the Paycock (1930) - the Film

[ Direction & screen-play by Alfred Hitchcock with a scenario by Alma Reville. Cast: Edmund Chapman as Captain Boyle and Sara Allgood as Juno; Sydney Morgan as Joxer; Sydney Maire O’Neill as Mrs Madigan; Kathleen O"Regan as Mary; John Laurie as Johnnie. ] For full account, see World Cinema Review (5 March 2013) - online; accessed 09.06.2018.

[ top ]

The Plough and the Stars (1936), dir. John Ford for RKO Radio Pictures, released 26 Dec. 1936; filmscript by Dudley Nichols; 72 mins., b&w; incls. use of contemp. newsreels. Cast: Barbara Stanwyck as Nora Clitheroe; Preston Foster as Jack Clitheroe; Barry Fitzgerald as Fluther Good; Denis O’Dea as The Young Covey; Eileen Crowe as Bessie Burgess; F.J. McCormick as Capt. Brennan; Una O’Connor as Maggie Gogan; Arthur Shields as Padraic Pearse; Moroni Olsen as Gen. Connolly; J. M. Kerrigan as Peter Flynn; Bonita Granville as Mollser Gogan; Erin O’Brien-Moore as Rosie Redmond; Neil Fitzgerald as Lt. Langon; Robert Homans as Timmy the Barman; Brandon Hurst as Sgt. Tinley (See International Movie Database / O’Casey [online; link extant 18.11.2010].)

| The Shadow of a Gunman (1923): |

|

| —Thomas Moore Raworth [1938-2013], cited by Trevor Joyce in Facebook - online (12 April 2017). |

|

The Silver Tassie - O’Casey “The Silver Tassie” sung by a London coal vendor, and resolved to give its title to his next play; quotes song ‘Gae fetch to me a pint o’ wine, / An’ fill it in a silver tossie; / That I may drink before I gae / A service tae my bonnie lossie.’ (quoted from O’Casey, Rose and Crown, 1956, p.31, in p.30 of Ronald G. Rollins, ‘Pervasive Patterns in The Silver Tassie’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 4, Winter 1971, pp.29-37.)

The Drums of Father Ned (1958) was planned for Dublin Theatre Festival with Alan McClelland’s dramatisation of Joyce’s Ulysses as Bloomsday and three mime plays and a radio play by Beckett; the Tostal secretary wrote to the Archbishop for permission to arrange a votive mass to inaugurate the Festival; a subsequent enquiry concerning ‘certain plays’ resulted in the refusal of permission. See further in Brendan Smith, ‘The Drums of Father Ned: O’Casey and the Archbishop’, in Des Hickey & Gus Smith, A Paler Shade of Green, 1972 [supra].

G. B. Shaw: Shaw told Denis Johnston that he regarded the second act of The Silver Tassie as one of the greatest pieces of writing for the stage; Johnston defers, but considers Shaw’s partiality due to his liking for Expressionism. (See ‘Did you know Yeats? And did you lunch with Shaw?’, in Des Hickey and Gus Smith, eds., A Paler Shade of Green (London: Leslie Frewin 1972), pp.60-72, p.68.)

[ top ]

People

Eileen O’Casey: born in London, née Reynolds, stage-name Carey, Eileen was appearing in musicals when Seán saw and fell in love with her; she played the first Minnie in The Shadow of a Gunman [‘Helen of Troy come to live in a tenement’, Plays, 1969, p.130] and wrote her biography of Seán as a corrective to misinformation in contemporary studies of her husband; d. Denville Hall, home for retired actors, London, April 1995.

W. B. Yeats: In 1926 on the first night of Seán O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars, [Yeats] thundered, ‘Is this to be an ever-recurring celebration of the arrival of Irish genius?’ Drums of Father Ned, withdrawn from Dublin Th. Festival, 1958; first prod. Lafayette, Indiana, 1959; printed 1960. For text of Yeats’s speech, see infra; For text of Yeats’s letter rejecting The Silver Tassie, see infra.

St John Ervine wrote: ‘Belfast, the Real Centre of Culture in Ireland’ (1944) in reply to O’Casey’s ‘There They Go the Irish’, in ‘They Go, the Irish: A Miscellany of War-Time Writing, compiled by Leslie Daiken (London: Nicholson & Watson 1944).

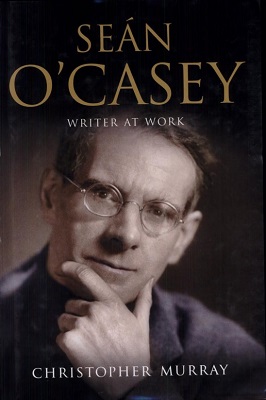

Flann O’Brien: O’Casey wrote an unsolicited letter of praise to O’Brien (as Brian O’Nolan) on the publication of An Béal Bocht. (See Anthony Cronin, No Laughing Matter, 1989, p.144.) Note however that ‘people’s poet, Jem Casey’, author of “A Pint of Plain is Your only Man” in At Swim-Two-Birds is probably intended as a type of Seán O’Casey, reflecting the fact that O’Brien was no fan of the playwright and that he regarded The Silver Tassie as little more than “bunkum and drool”. (See Alan O’Riordan, Books Ireland, review, April 2005, p.92, quoting Christopher Murray, Seán O’Casey: Writer at Work, 2004.)

[ top ]

Tyrone Guthrie: Guthrie’s account of the first performance of The Bishop’s Bonfire: ‘At first the audience played up - supposedly anti-Irish or anti-clerical lines were received with jeers and hisses or, by the minority, with exaggerated laughter and applause. But gradually it became apparent that the jokes were not of the finest vintage, the satire not very pointed, the plot a little “hammy” and the performance, in spite of manful efforts by Eddie Byrne and Seán Kavanagh, a little amateurish. By the end of the second act, the excitement had fizzled away. The audience was like a wedding party after the departure of the bride; after the elation of the nuptials and the unwonted champagne comes the reaction; a melancholy, punctuated by hiccups./By the end of the last act torpor was turning to positive vexation. Cyril Cusack came forward at the curtain call and made a long prepared speech in Irish. After thanking the audience for its wonderful reception, he gave a harangue on behalf of tolerance and liberty. Under this final douche of cold water, The Bishop’s Bonfire, which had never quite blazed, fizzled into a heap of damp ashes. (Guthrie, A Life in the Theatre, Hamish Hamilton 1960, pp.267-69; see more extensively under Guthrie.)

John Boyd: Programme of Lyric Players Th. production of Irish Premiere of Cock-a-doodle Dandy (Nov. 1975: 25th Anniversary Season, ‘From Farquhar to Friel’) contains Programme note by John Boyd.

Samuel Beckett (1): Following Beckett’s withdrawal of performance rights to his plays from Dublin theatres arising from the supposed censorship of Seán O’Casey’s Drums of Father Ned, he wrote to Barney Rosset: ‘The Roman Catholic bastards in Ireland yelped Joyce and O’Casey out of their “Festival”, so I withdrew my mimes [Acts Without Words I & II] and the reading of All That Fall to be given at the Pike. Now the whole thing seems to be off!’ (20 February 1958, held in Grove Press Collection, University of Syracuse, NY.) O’Casey had written to The Irish Times (17 February 1958): ‘The Archbishop doesn’t know (or doesn’t care) that a work by Joyce or Beckett or even by O’Casey, performed in Dublin, is of more importance to Dublin than it is to any of those authors; that outside Dublin is a wide, wide world, and that this wide place is Joyce’s oyster, Beckett’s oyster, and even O’Casey’s oyster, or that these voices, hushed in Dublin, will be heard in many another place.’ (Both quoted in Martha Fehsenfeld & Lois More Overbeck, ‘The Correspondence of Samuel Beckett: Windows on the Work’, in Beyond Beckett [Princess Grace Irish Library Series], Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1999.)

Samuel Beckett (2): Beckett called O’Casey ‘a master of knockabout in this very serious and honorable sense - that he discerns the principle of disintegration in even the most complacent solidities, and activates it to their explosion’; especially praised one-acter The End of the Beginning, in which the two comic characters Darry Berrill and Barry Derill end ‘in an agony of callisthenics, surrounded by the doomed furniture.’ (Cited in Anthony Cronin, Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist, 1996, p.58.)

Don Gifford: In illustrating the point that the Irish arts were still self-censoring after the repeal of the Censorship Act, Don Gifford writes, in Annotations to James Joyce [rev. edn. (Cal. UP 1882): ‘For example: the first Dublin performance (Oct. 1977) of Sean O’Casey’s burlesque Cock-a-Doodle Dandy (1949) was introduced with an apology in the Abbey Theatre program lest the play take the audiences unawares and anger ‘religious, national and social sensibilities ... especially for [its] undeniably crude caricatures of [Irish] patriots, politicians, and priests.’ (Gifford, op. cit., p.10.)

Conor Cruise O’Brien: For an account of the Plough and the Stars riot, see O’Brien, Ancestral Voices, Religion and Nationalism in Ireland (Dublin: Poolbeg 1994), pp.123ff.

Benedict Kiely: In Drink to the Bird (London: Methuen 1991), Kiely records that Mother Polycarp at Cappagh Hospital, where he was treated for spinal tuberculosis in 1938-39, was br. of Dr. Cummins, eye-specialist and friend of Seán O’Casey.

Lanthern Theatre : The Lanthern Theatre dramatisation of O’Casey’s Autobiographies, consisting of Pictures in the Hallway (Lanthern 1966), Drums Under the Window (Lanthern 1968), and Inishfallen, Fare Thee Well all produced in an eight-hour marathon on 24 July 1972 was cited in Guinness Book of Records at the time. See David Krause, ‘Remembering Liam: An Epiphany of Friendship’, in Irish Literary Supplement, ([q. iss.] 1992), pp.26-30.

Anti-clericism: ‘Bonfire under a Black Sun’, in The Green Crow (1957), pp.122-45, is O’Casey’s defence of the critique of Irish clericism in The Bishop’s Bonfire.

Portraits: Pencil-portrait of 1930 by Harry Kernoff in National Gallery of Ireland, reprinted in Brian de Breffny, Ireland: A Cultural Encyclopaedia (London: Thames & Hudson 1983), p.139; Seán O’Casey by Patrick Tuohy, pencil, Municipal; see Irish Portraits Exhibition, Ulster Mus. 1965. See also Harry Kernoff’s portrait, signed [1930], purchased from Lady Gregory Collection 1932 [National Gallery of Ireland].

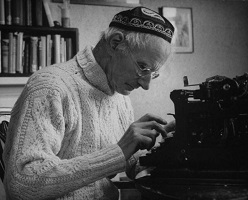

Work methods: O’Casey’s wife Eileen disclosed that O’Casey habitually hummed when he worked. (See Ronald G. Rollins, ‘Pervasive Patterns in The Silver Tassie’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 4, Winter 1971, pp.29-37, p.30.)

Abbey fire (1951): The Abbey Theatre’s original premises - being the Mechanics Hall in Lower Abbey Street, Dublin, refurbished with money provided by Annie Horniman, a wealthy English patroness of the Literary Revival - burnt down accidentally in 1951 during a production of The Plough and the Stars by O'Casey - a play which ends with the song, “Keep the Home Fires Burning”. It then located to the Queen’s Theatre on Pearse Street.

[ top ]

|