Tomás Ó Criomthain (1856-1937)

Life

| (1856-1937) [anglice Thomas O’Crohan;] b. Great Blasket Island; a small-holder and a fisherman; one of ten children born to his parents, two boys of whom drowned, one in a fall from a cliff and the other trying to rescue a Gaelic-League visitor (Miss Nicholls), while two girls died of measles; he enlisted was as a Gaelic League teacher Brian Ó Ceallaigh, 1917 - who read him Pierre Loti and Maxim Gorky and provided writing materials; his daily journal of island life was edited by Pádraig Ó Siochfhradh [pseud. “An Seabhac”] as Allagar na hInise [Island Talk] (Dublin 1928; new edn. 1977); |

| Ó Ceallaigh encouraged Ó Criomhthain to write his life which he did only as An tOileánach (1929) after reading Gorky’s 3-vol. autobiography - the genre being alien to his communal culture; visited on the island by num. Gaelic scholars incl. Carl Marstrander and Robin Flower - who trans. his best-known work as The Islandman (1934), ending ‘there will not be our likes again’; later satirised by Flann O’Brien in The Poor Mouth, especially in respect of Ó Criomthain’s constant allusions to an drochshaol [‘bad times]’ |

| Robin Flower took dictation from Ó Criomthain, later to be published as Seanchas ón Oileán Thiar (ed. Séamus Ó Duilearga 1956); Ó Criomthain died on the Great Blasket in 1937; the island was evacuated by the Irish Government in 1942. DIW DIB DIH OCIL |

|

|

Tomás Ó Criomthain |

Seán Ó Criomthain, Eilbhís Ní Shuilleabháin, Tomás Ó Criomhthain & Muiris Ó Suilleabháin. |

[ top ]

Works

|

| Translation edns [English] |

|

|

|

|

|||

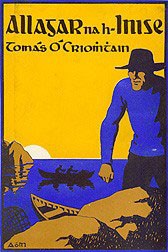

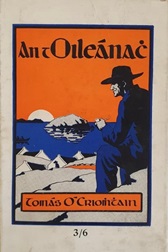

| The cover-art for Ó Criomhthain’s Irish books was executed by Austin Molloy (signing himself “AÓM”). [Information supplied by Feargal Whelan at at 20th Irish Art on Facebook - moderated by David Britton (17.09.2024). See also the caricature of his covers by Se´a;n Ó Suilleabh´a;in connected with the publication of An Beál Bocht by Flann O'Brien - as infra. |

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

[ top ]

Commentary

John McGahern, review of The Islandman, in Irish Times (2 Nov. 1991); ‘Nowhere in the work does he attempt to describe the little island he lives on in the Blaskets ... The island is simply there as a human habitation, a bare foundation of earth on which people live and move. A field is only described as it is reclaimed and cultivated. A strand is there to be crossed, a sea to be fished, a town to be reached, a shore to be gained, walked upon, lived upon.’ (Note: McGahern wrote several times on Ó Criomhthain [O’Crohan] - both in the Canadian Journal of Irish Studies and The Irish Times but also as a significant part of his essay "What is My Language?", in the Irish University Review [rep. in Love of the World, p.260ff. - as infra.]

Declan Kiberd, ‘Homeric Islandman Tomás Ó Criomthain’, in The Irish Times (4 Nov. 2000): ‘[…] If the islanders were inadvertant poets, they were also instinctual anarchists. Synge was impressed by the versatility of a generally bilingual people who knew no division of labour, their work changing with the seaons from fishing to kelp burning, from cutting shoes to thatching houses, from building cradles to making coffins, in a way that kept them free from the dullness and monotony of industrial life.’ (From Irish Classics, Granta, Nov. 2000).

Catherine Foley, review of Seán Ó Coileain, ed., An tOileánach by Tomás Ó Criomthain (Cló Talbóid), 346pp., in The Irish Times (4 Jan. 2003), Weekend, p.9. Quotes Flann O’Brien: ‘the superbest of all books I have read [...] its impact was explosive. In one week I wrote a parody of it called An Béal Bocht . This prolonged sneer will be republished shortly. My prayer is that all who read it afresh will be stimulated into stumbling upon the majestic book upon which it is based.’ (No source; quoted by Sean Ó Mordha in launching the book.) Foley also quotes John McGahern: ‘[what finally emerges is a poetry which] seeps through the book as a whole, like water or the sea air round the place itself, so persistent is the form of seeing and thinking, and this, equally persistent, seems all the time to find its right expression. Unwittingly, through the island frame, we have been introduced to a complete representation of existence.’ (Irish Review, 1989).

[ top ]

John Wilson Foster, ‘The Islandman: The Teller and the Tale’, in Between Shadows: Modern Irish Writing and Culture (Dublin: IAP 2009), pp.17-28: ‘[...] Here is experience formalized into the tradition of the folk-tale. The Islandman is the hybrid progeny of the authority of tradition and the authority of experience.’ (p.18.) Of the absence of birds in the narrative: ‘The truth, I suppose, is that what was not readily at hand and usable or edible was hardly noticed at all. / Indeed, there is in The Islandman an almost phagic relation to life: [18] O Crohan’s register of food intake seems in excess of his wish to tell us how hard life was, how islanders had to hoard or search for food.’ (pp.18-19.) [Cont.]

John Wilson Foster (Between Shadows: Modern Irish Writing and Culture, 2009) - cont.: ‘In The Irish Tradition, [Robin] Flower recalls listening spellbound to an old man (a Blasketman, I infer) reciting a long tale. “I have kept you from your dinner with my tales of the fiana”, the teller apologizes. “You have done well”, Flower replies, “for a tale is better than food” (op. cit. 1947, p.106). In The Islandman, the two are curiously connected and co-dominant. Food is the very stuff of life - what is gathered, hunted, grown, and so too is the tale, be it anecdote (experience barely processed), the local legend (midway between the memory of an historical occurrence, and its complete processing into the tradition of a Finn tale or international folk-tale), or the folk-tale proper.’ (p.20.) [Cont.]

John Wilson Foster (Between Shadows: Modern Irish Writing and Culture, 2009) - cont.: ‘O Crohan’s sense of the world is not, on the evidence of The Islandman, primarily theocentric or Christian, but rather anthropocentric in the manner, say, of the traditional ballad. The written version of his worldview shares with the ballad that primal sense of humanity’s mysterious relation to fate; it shares that quality which Padraic Colum identified in folk-tales as "reverie", a state of mind midway between dream and reality: life distilled, purged or irrelevance and circumstance (Colum, Storytelling New and Old, NY: Macmillan 1968, pp.14-15). [...] On the strength of The Islandman, I believe it was on the older consolation of philosophy rather than on nineteenth-century Christianity that O Crohan drew [...]’ (p.23.)

Keith Ridgway, review of The Islander, by Tomás O’Crohan, trans. by Garry Bannister & David Sowby, in The Irish Times (13 Oct. 2012), Weekend Review, p.12: ‘Here is a man who lives a hard, straightforward life, who “ploughs the sea” and works the land, who grows up and marries and has children, who gets drunk often, and who gets learning in fits and starts but seems to take to it, and who settles into an old age of Gaelic Revival-prompted reminiscences. But there are so many repetitions, so much attention given to minor occurrences and so little to major ones, that it becomes – like the life perhaps – an exasperating and tiresome chore. / O’Crohan was asked for this book by people who called at his door – a fact that shapes it and ultimately, I suspect, smothers it. He was writing for a very immediate and specific audience. He alludes at times to a wider readership, but he knew that what he wrote would be read in the first instance by men who would turn up at his house every few months looking, and paying, for more. And you can feel in his tone and his focus a man who has no wish to be dishonest, who has been convinced of the anthropological worth of the project, but who makes of his life a list of things he’s done, easily told things, things in which he takes pride – which he balances with a bombastic humility – and who as a result gives us a peculiarly superficial idea of himself, delivered in an unrelenting, exculpatory banter. [...] Late on in the book, he writes: “Of all the terrible things that have ever happened to me, dealing with death has always been the most terrible of all.” How could it be otherwise? But you wouldn’t know it from anything else in The Islander. And I can only think of those linguists and anthropologists sitting in Tomás O’Crohan’s house, asking him to write down the facts of his life for them. And he spending a few hours every week giving them whatever seemed to please. And I can imagine him, and I really hope this is true, going out of his house then and being a far fuller person than this book suggests.’ (See full text in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Reviews”, via index, or direct.)

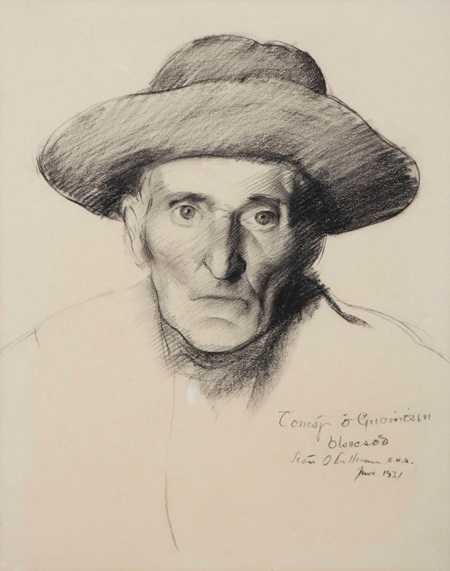

Pencil portrait by Seán Ó Suilleabháin

[ top ]

Quotations

The Islandman (trans. Robin Flower; 1st edn. 1927; OUP 1985), HOME RULE: ‘A few years went by like this, and the fishers didn’t want for shillings, as the boats came to our very threshold with yellow gold on board to pay for the catch, however big the haul might be. Just at the time that these companies were sending their boats to us the talk was beginning through Ireland about self-government, or Home Rule, as it is called in another language. I often told the fishermen that Home Rule had come to the Irish without their knowing it, and that the first beginning of it had been made in the Blasket now that the yellow gold of England and France was coming to our thresholds to purchase our fish, and we didn’t give a curse for anybody.’ [155] COURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE: ‘She hadn’t been home many days when she started out again with a man she preferred to the first one. Very few people accompanied them, for they thought it a rather odd proceeding. The girl had no one with her. Though there wasn’t a pin to choose between the two men, it’s plain the girl had some reason for preferring one to the other. The boy she jilted didn’t leave his oars idle. He went as far a Tralee for a wife - the daughter of a Dunquin widow who was in service there. / ... I was a near relation of the girl’s too, though I didn’t quarrel with her doing what she did.’ [142] SEAWEED: manure, labour of spreading [167]. FIANNA: ‘And though, as far as looks went, I was no match for the Fenians of old, nobody could say a word against me for what I was - I was quick and deft, and knew what was what. [85] We set the boats’ sterns to land and their prows to sea, as the mighty heroes used to do in the days of old, and started out through the channel.’ (pp.85-86.) On his CHILDREN [146-47]. (Cont.)

The Islandman (trans. Robin Flower; 1st edn. 1927; OUP 1985) - cont.: LAW & ORDER: ‘for the scoundrels [agents and bailiffs] used to be confiscating cattle every day from anybody who had them, for in those days they didn’t give a rush for the law itself, and the poor had no means of taking up a case against them.’ [166] IRISH LANGUAGE, ‘so ended the two who put the sound of the Gaelic language in my ears the first day. The blessing of God be with their souls!’ [170] MEAT-EATERS: ‘The poor people of the countryside were accustomed to say that they fancied they would live as long as the eagle if they but had the food of the Dingle people. But the fact is that the eaters of good meat are in the grave this long time, while those who live on starvation diet are still alive and kicking.’ [101] incident with 3 FINE WOMEN [157]. PERORATION: ‘[...] to set down the character of the people about me so that some record of us might live after us, for the like of us will never be again. ... that when I am gone men will know what life was like in my time and the neighbours that lived with me. / Since the first fire was kindled in this island none has [244] written of his life and his world. I am proud to set down my story and the story of my neighbours. The writing will tell how the Islanders lived in the old days. [Expresses hope of seeing his parents again in Heaven] and that I and every reader of this book after me will meet them there in the Island of Paradise.’ [245 END] (See also Robin Flower’s prefator remarks on style, under Flower, Quotations, supra.)top ]

The Islandman (trans. Robin Flower; 1st edn. 1927; OUP 1985) - cont.: ‘My father was a middle-sized man, stout and strong. My mother was a flourishing woman, as tall as a peeler, strong, vigorous and lively, with bright, shining hair. But when I was at the breast there was little strength in her milk, and besides that I was an “old cow’s calf”, not easy to rear. For all that, the rascal death carried off many a fine young ruffian and left me to the last. I suppose he didn’t think it was worth his while to shift me. I was growing stronger all the time and going my own way wherever I wanted, only that they kept an eye on me to see I didn’t go by the sea. I wore a petticoat of undressed wool, and a knitted cap. And the food I got was hen’s eggs, lumps of butter, and bits of fish, limpets and winkles - a bit of everything going from sea or land. / We lived in cramped little house, roofed with rushed from the hill We had a post bed in the corner, and two beds in the bottom of the house. There used to be two cows in the house, the hens and their eggs, an ass, and the rest of us.’ [Cont.]

[ top ]

The Islandman (trans. Robin Flower; 1st edn. 1927; OUP 1985) - cont.: ‘This is a crag in the midst of the great sea, and again and again the blown surf drives right over it before the violence of the wind, so that you daren’t put your head out any more than a rabbit that crouches in his burrow in Inishvikillaun when the rain and the salt spume are flying. ... It was our business to be out in the night, and the misery of that sort of fishing is beyond telling. I count it the worst of all trades.’ [...; cont.]

The Islandman (trans. Robin Flower; 1st edn. 1927; OUP 1985) - cont.: ‘It wasn’t the drink that made us want to go where it was, but only the need to have a merry night instead of the misery that we knew only too well before. What the drop of drink did to us was to lift up the hears in us, and we would spend a day and a night ever and again in company together when we got the chance. That’s all gone by now, and the high heart and the fun are passing from the world. Then we’d take the homeward way together easy and friendly after all our revelry, like the children of one mother, none doing hurt or harm to his fellow.’ [...; cont.]

The Islandman (trans. Robin Flower; 1st edn. 1927; OUP 1985) - cont.: ‘One day there will be none left in the Blasket of all I have mentioned in this book - and none to remember them. I am thankful to God, who has given me the chance to preserve from forgetfulness those days that I have seen with my own eyes and have borne their burden, and that when I am gone men will know what life was like in my time and my neighbours that lived with me.’ (Quoted in part in P. J. Kavanagh, Voices in Ireland, 1994, p.200.) Also, ‘People say that the wheel is always turning, and that’s a true saying, for in the part of the world that I have known it has turned many times.’ (The Islandman, OUP 1978 Edn., p.167; quoted in Ivor Faulkner, UU MA Diss., 2007.)

[ top ]

[ top ]

Flann O’Brien: In The Poor Mouth, O’Brien serves up a parody of the well-known ending of The Islandman: ‘Yes! I think that I shall never forget the Gaelic feis which we had in Corkadoragha. During the course of the feis many died whose likes will not be there again and, had the feis continued a week longer, no one would be alive now in Corkadoragha in all truth.’ (The Poor Mouth [An Beal Bocht], trans. Patrick C. Power, 1973; Picador 1975, p.61;

Note also the resemblance between O’Brien’s opening in The Third Policeman and the account of O’Crohan’s parents, quoted by P. J. Kavanagh [as supra].

Eibhlín Nic Niocaill [Evelyn [or Eveleen] Nicolls] (1): The girl whom Tomás Ó Criomthain’s son tried to save from drowning, he himself drowning in the process, was a platonic friend of Patrick Pearse. There is a life of her by Micheal Ó Duishlaine [or Dubhshlaine] (Oigbhean Uasal ó Phríomhchathair Éireann, Conradh na Gaeilge, 1992).

Eibhlín Nic Niocaill (2): J. W. Foster writes of a detailed account of the drowning of Eileen Nicholls [sic] in James and Gretta Cousins, We Two Together (1950). See Foster, ‘The Islandman: The Teller and the Tale’ [Chap. 2], Between Shadows: Modern Irish Writing and Culture, Dublin: IAP 2009), p.25; see further under James Cousins, supra.)

Island funeral: Coincidently the geologist Thomas Mason was nearby when the tragedy took place and recorded details of the funeral, which reminded him of the black gondalas of which ‘take the place of the mourning coaches’ in Venice (The Islands of Ireland: Their Scenery, People, Life and Antiquities, London: Batsford 1936, p.100; quoted in J. W. Foster, op., cit., idem.)

[ top ]