|

[ top ]

Works| Fiction |

|

|

|

| Commentary |

|

Miscellaneous |

|

| Reprints |

|

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

Bibliographical details

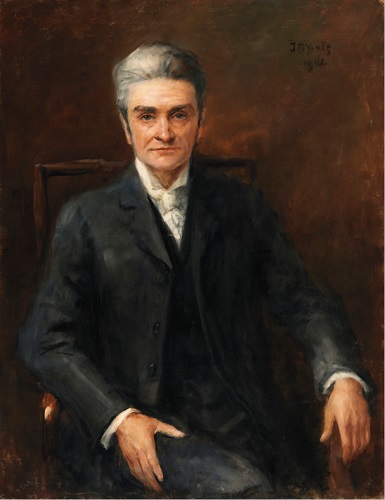

Standish James O’Grady: The Man and His Work, by Hugh Art O’Grady, with a foreword by Alfred Perceval Graves; also A Tribute by “AE” [George Russell]; A memory and an appreciation by Alice L. Milligan, and a postscript by Prof. David Morton (Dublin: Talbot Press 1929), 84pp., [front. port.] - see full text, attached.

[ top ]

Commentary

See separate file - infra.

Quotations

Red Hugh’s Captivity (1889), Introduction: ‘The history of Ireland during the sixteenth century is the history of a revolution, of the successive steps by which a radical and organic reconstitution of society was effected. / The Elizabethan conquest was, in my opinion, as inevitable as salutary, and the terrors and horrors which accompanied it, to a considerable extent, a necessary condition of its achievement. These petty kings and princes had to be broken once for all. In blood and flame and horror of great darkness it was fated that Ireland should pass from barbarism to civilisation, from the wild rule of ‘monocracies’ to the reign of universal law. If it was England that presided over that death and new birth, the fact, I think was to Ireland’s gain and not loss. It would certainly ill become an author, who is now enabled to address an audience so vast, to regret the events which have made it possible. [...] Whether our future be one of greater self-government, or of a closer and more vital union with England, we are and will remain part of the vast world-subdividing race that speaks the English tongue [..] Between Ireland and her incorporation for ever with this mighty English-speaking race stood the Irish chiefs of the sixteenth century. The expanding genius of civilisation found such independent captains and princes, here as elsewhere over Europe, an intolerable bar to progress. Their extermination or subjugation was not only necessary but inevitable. And yet the men themselves have strong claims upon the sympathy of generous minds, more especially when their rebellions and their ruinous overthrown alike lie so far behind us in the quiet depths of the past ... their wild lives not untouched with the medieval spirit of chivalry and romance. (Red Hugh’s Captivity, 1, pp.3-5; quoted with ellipsis in Cahalan, Much Hatred, Little Room: The Irish Historical Novel, 1983.)

The Bog of Stars (1893) - cont.: ‘“Bog” is not a beautiful word though melodious Milton found a place for it in his Paradise Lost. It sounds better in Gaelic, for it is pronounced bogue, and means “soft”. The thing signified has a doubtful reputation. Bogs are glorious in the eyes of sportsmen, a valuable property when they produce turf, and when they do not, blots on the face of Nature, upon which the improver wages constant war by drains, plantations, and other improvers’ methods. On the whole, bogs are not popular, and yet sometimes at night, when stars fill the sky, bogs reflect their glory. Then the fowler, home-returning, tired and meditative, with his tired dogs at his heels, pauses for a moment beside some pool, and looks down and not up. It is a feature of bogs which has not escaped the notice of our poet, Mr. W. B. Yeats: “There the wandering water gushes / In the hills above Glencar / In pools amongst the rushes / That scarce could bathe a star.”/ The old name-makers of Ireland noticed it too. There is an Irish bog called Mona-Reulta, or the Bog of Stars. Don’t ask me to place in upon the map; probably it has long since yielded to the asiduous improver,and now grows corn for man and green grass for cattle, and is not starry any more. All I know is that it flourished once and was starry, and figures in a tale known lang syne, but improved out of memory, as probably Mona-Reulta itself has been.’ (See ‘The Bog of Stars’, in George Birmingham, ed., Irish Short Stories, 1932, pp.60-71; 60-61). [Cont.]

The Bog of Stars (1893) - cont. ‘[the soldiers had] a lad pinioned hand and foot, with a stone fastened to his ankles. He was perfectly still and composed; there was even an expression of quiet pride in his illuminated countenance. He was to die a dog’s death, but he had been true to his star. ... One, two, three, a splash, a rushing together in foam of the displaced water, then comparative stillness, while bubbles continually rose to the surface, and burst. Presently all was still, black and still.’ [...; 70.]; A pert black head clambered about aimlessly in a little dry and stunted willow tree that grew by the drummer’s pool hardly a foot high. / then the sun set, and still night increased, and wher the drummer boy had gone down, a bright star shone’; it was the evening star, the star of love, which is also the morning star, the star of hope and bravery.’ (Ibid. [in Birmingham, op. cit., pp.70-71; End.)

Note: In this story, a young drummer in the service of Lord Mountjoy and Thomas Lee, remembering the days of happiness at the court of the ‘Raven’ (Hugh O’Neill), sounds his kettle drum just when the English forces are marshalling at attack on O’Neill’s strong-hold, and is trussed up and drown in the bog in payment.

[ top ]

Ulrick the Ready (1899), Preface, ‘[the novel was] formed out of the study of an eventful period, that of the Spanish Armada, which Philip III depatched against these islands in 1602. [...] This stormy century lends itself better than the rest to the work of the historical novelist [...] the Celtic principality [of Pt I] is the region which has already been celebrated by Mr Froude in his spirited novel, the Two Chiefs of Dunboy. Indeed, the person referred to as son of the Knight was the ancestor of one of Mr Froude’s two chiefs.’ Writes of ‘Glenagarriff, one of the loveliest spots in the world [2] its rough casements softened into some liquid flowing synomym would have [entered] the Faery Queene; ‘The Nest of Eagles [Keim-an-eige], home of his dear master and mistress, the pride, the glory, and trust of his clan ... “nest of eagles”... ‘Then it was the wise purpose of the Spanish Government not to embarrass itself in the hopeless task of endeavoring to govern Ireland but straightway to organise the military Irish for the invasion of England where a great Catholic party was even then ready and eager to co-operate.’ [168] [See further under Notes, infra.]

Ulrick the Ready (1899) [on The O’Sullivan:] ‘we see what he does not, the sword suspended by a single hair, revolving, glittering, above his head; perceive the hand, invisible to him, writing strange characters on the wall; perceive the coming vengeance which will sweep him and his state and power, castle and clan, into the dust-heap of things that were, to repose there with all the extinct tyrannies of the earth.’ (Ulrick, p.156; quoted in Cahalan, Much Hatred, Little Room: The Irish Historical Novel, 1983; poss. err. in this record for Red Hugh’s Captivity.)

History of Ireland: Critical and Philosophical - Part 1: The Heroic Period (1878), ‘Preface’: ‘[..] One of the most interesting features of early Irish civilisation, the religious feature, is also unfortunately the most obsecure. In the absence of clear philosophical statement by the monks, we are obliged to fall back upon the tales and poems ...Now, if we had a sufficient quantity of pre-Christian Irish literature, there would be no loss sustained by the unfortunate reticence of the ecclesiastics ... The bards were but the abstracts and brief chronicles of their own time [..//..] The advent of Christianity ruined the bards. the missionaries felt instinctively that the bards were their enemies ... The degradation of the bardic class was therefore essential to the success of the missionaries. Both could not live in the same country ... St. Patrick and his compeers and fellow-missionaries, seem to have been rude, uneducated men. Their Latin is rude, clumsy, and ungrammatical. His own compositions are so bad, that they have been considered forgeries [..//..] On the other hand, in the time of Adamnan, three centuries later, the monks had perfected a splendid latin style, enriched with contributions from the Greek and Hebrew, and giving the reader the impression that they were the intellectual lords of the land. In the bardic literature of the period, we look in vain for anything which might be considered in profane literature the equivalent of The Life of St. Columbanus’ [..//..] In fact, the position of the contending parties had been reveres. The bards now amused only farmers and tradesmen, while the monks crowned kings, and trained the minds of princes. The consequence was, that secular literature did not flourish, or flourished only in the monasteries, where it was not the chief thing, but an ornament of the monastic mind.’ (Vol. 1 [1881 Edn.]., pp.ix-xvii). [Cont.]

| History of Ireland - Part I: Pre-historic Ireland |

| [Preface:] |

|

| Chap. 1: “Testimony of Rock and Cave”* |

| ‘Pleistocene Ireland’ |

|

‘Of planetary epochs, the Eocene and Meiocene have slowly receded into the past, their huge cycles having been accomplished, and the Pleistocene, with new tribes of animals, and amongst them one destined to the mastery of the rest, is advancing over North-Western Europe. The uncouth monsters to whom Cuvier and others have affixed names as uncouth as themselves, have disappeared. The hipparion, a delicate equine creature, will not dart through the woods any more. The mastadon [...] will not shake the earth again. The stag of Polignac, the early field bear, the megatherium, the trogotherium, are all gone. The pleisiosauros, kind of the lizard tribe, will not enjoy the heat of the sun any more. His horrid length he has committed to the safe-keeping of the mud, that will one day be marble [...; 1]. |

|

[ top ]

History of Ireland: Critical and Philosophical - The Heroic Period (1878): ‘Now it is not to be supposed that the heroes and events of this wonderful period are to be lightly passed over - a period which, like the visible firmament, was bowed with all its glory above the spirit of the whole nation. Those heroes and heroines were the ideals of our ancestors, their conduct and character were to them a religion, the bardic literature was their Bible. It was a poor substitute, one may say, for that which found its way into the island in the fifth century. That is so, yet such as it was under its nurture, the imagination and spiritual susceptibilities of our ancestors were made capable of that tremendous outburst of religious fervour and exaltation which characterised the centuries that succeeded the fifth, and whose effect was felt throughout a great portion of Europe. It was the Irish bards and that heroic age of theirs which nurtured the imagination, intellect, and idealism of the country to such an issue. Patrick did not create these qualities. They many not be created. He found them, and directed them into a new channel.’ ([q.pp]; quoted in Denis Donoghue, ‘Romantic Ireland’, in We Irish: Essays in Irish Literature and Society, 1986, pp.27-28.)

“Dawn”, [being] the first chapter of his History of Ireland: The Heroic Period (Dublin 1878): ‘There is not, perhaps, in existence a prodoct of the mind so extraordinary as the Irish annals. From a time dating more than two thousand years before the birth of Christ, the stream of Milesian history flows down uninterrupted, copious and abounding, between accurately defined banks, with here and there picturesque meanderings, here and there flowers lolling upon those delusive waters, but never concealed in mists, or lost in a marsh. As the centuries wend their way, king succeeds king with a regularity most gratifying, and fights no battles, marries no wife, begets no children, does no doughty deed of which a contemporaneous note was not taken, and which has not been incorporated in the annals of his country. To think that this mighty fabric of [239] recorded events, so stupendous in its dimensions, so clear and accurate in its details, so symmetrical and elegant, should be after all a mirage and a delusions, a gorgeous bubble, whose glowing rotundity, whose rich hues, azure, purple, amethyrst and gold, vanish at a touch and are gone, leaving a sorry remnat over which the patriot disillusioned may grieve.’ (q.p.; quoted in R. F. Foster, The Story of Ireland: Telling Tales and Making It Up in Ireland, London: Allen Lane/Penguin 2001, pp.239-40 [notes to Chap. 1: “The Story 9of Ireland’].) [See also further quotation in Foster, infra.]

History of Ireland: Critical and Philosophical - The Heroic Period (1878), p.v: ‘I desire to make this heroic period once again a portion of the imagination of the country, and its chief characters as familiar in the minds of our people as they once were.’ (Quoted in Declan Kiberd, Inventing Ireland, 1995, p.196.)

Note that Kiberd goes on to delineate a scene at Bray when George Russell [AE] is preaching about the return of ancient Irish heroes, and further quotes O’Grady as saying, “We have now a literary movement, it is not very important, [...] it will be followed by a political movement, that will not be very important; then must come a military movement, that will be important indeed’ [citing Yeats’s Autobiographies, p.424 - as quoted more fully in Commentary, supra].

[ top ]

History of Ireland: Critical and Philosophical - The Heroic Period (1878), ‘I cannot help regarding this [heroic age] and the great personages moving therein as incomparably higher in intrinsic worth than the corresponding ages in Greece. In Homer, Hesiod, and the Attic poets there is a polish and artistic form, absent in the existing monuments of Irish heroic thought, but the gold, the ore itself, is here massier and more pure, the sentiment deeper and more tender, the audacity and freedom more exhilariting, the reach of the imagination more sublime, the depth and the power of the human soul more fully exhibit themselves [...]’ (Vol. 1, p.201; quoted in Fiona Macintosh, Dying Acts: Death in Ancient Greek and Modern Irish Tragic Drama, Cork UP 1994, p.8; also in Len Platt, ‘Corresponding with the Greeks: An Overview of Ulysses as an Irish Epic’, in James Joyce Quarterly, Spring 1996, p.516.)

“Dawn”, [being] the first chapter of his History of Ireland: The Heroic Period (Dublin 1878): ‘Its symbolism gleaming brihter and brighter against the waning light of Rome ... it glitters like the morning star before the eye of the historians. That group of green mounds, palisaded and dyked, surrounded with painted wicker houses, is the central harmonising point of the wild chaos which surges and bellows in the darkness and the haze - starlike now, it will itself be one day a sun.’ (p.47; quoted in R. F. Foster, The Story of Ireland: Telling Tales and Making It Up in Ireland, London: Allen Lane/Penguin 2001, pp.239-40 [notes to Chap. 1: “The Story of Ireland’].) [See also ealier quotation in Foster, infra.]

History of Ireland: Critical and Philosophical, Vol. I (1881): ‘To Daithi [son of Niall of the Nine Hostages] succeeded, 428 a.d., Laegairey, son of the great Niall. He was slain, according to the annalists, in 458 a.d., by the Sun and Wind, between two mountains, Erin and Alba, situated somewhere on the banks of the Liffey - “The elements of God, whose guarantee he had violated,/ Inflicted the doom of death upon the King.” (Four Masters, p.145). / Laegairey had been taken prisoner by the Leinster men while collecting the Boromean tribute and to procure his release had sworn by the Sun and Wind that he would never again renew the hateful impost. Having recoverd his freedom he sacrilegiously invaded Leinster at the head of an army, and raised upon the inhabitants the Boroma first exacted by Tuhal Tectmar. All history shows that powerful nations do not hesitate to break through treaties contracted with weaker foes [... &c.] (Cont.)

[Cont:] The confederacy which supported Laegairey and the Ard-Rieship, and which shared with him the great Boromean tribute, refused to ratify his private undertaking, suggesing to him doubtless, as ambition and greed backed by overweening military powers always will, sophistical reasons why such an engagement should not bind, and induced or compelled him once more to invade Leinster and enforce the ancient prerogatives of his ancestors. Doubtless, had Laegairey refused to obey his feudatories, the great confederacy of which he was the head would have supported him, which, of course, is but a palliation, not an excuse.

[Cont.:] But there is this proof of the existence of a public conscience, a conscience formulated in the ethnic and pre-Christian ages, that conscience which underlies and makes sublime and ever-interesting the great heroic literature of Ireland, that if the crime was monumental so too was its condemnation. The Irish bards and the monks who have followed them and adopted their views and feelings, have set down in the annals a great crime, and attached to it a great stigma. The crime, its punishment, and its condemnation stand out clearly in the chronicles as a solemn warning and example to all treacherous and treaty-breaking Kings. The Sun and Wind slew the Irish Ard-Rie because he had broken faith with his enemies and taken their name in vain. [pp.414-15; Notes also that Laegaire/Laoghaire corresponds to fortified Kingstown Harbour].

[Note that the chronology here constrasts with that in the New History of Ireland, ed. T. W. Moody, et al., in which the death of Nial is set about 527.]

[ top ]

Pacata Hibernia; or, A History of the Wars in Ireland, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth... : first published in London, 1633, / edited and with an introduction and notes by Standish O’Grady, 2 vols. (London: Downey & Co. 1896).

|

|

| In a later (unnumbered) footnote at the confusion of the narrative of the defeat of the Irish rebels at Kinsale, he writes at similar length about the tactical reasons for that defeat - reflecting on its treatment by native Irish historians in this matter: |

|

| Finally, in a footnote to Stafford’s quotation of the Spanish General Juan D’Aguila’s memoir of events at Kinsale, he remarks: |

|

| This seems to be a synopsis of his general theory of the failure of Irish society in face of the centralised monarchy of Norman England. O’Grady devotes a short footnote to asserting that that Aguila never spoke the phrase so often attributed to him: “Surely Christ never died for these people” - though, he tells us, “[o]ne of his officers did use that expression.” (p.[71]n. |

[ top ]

Selected Essays and Passages [1918]|

‘The political understanding of Ireland to-day is under a spell and its will paralysed. If proof be demanded for this startling assertion, how can proof to any good result be supplied. It is the same spellbound understanding which will consider the proof. (p.174). |

| See also remarks on the Anglo-Irish, infra. |

Irish archaeology: ‘In the rest of Europe there is not a single barrow, dolmen, or cist, of which the ancient traditional history is recorded; in Ireland, there is hardly one of which it is not.’ (Early Bardic Literature, 1879; cited in P. J. Kavanagh, Voices in Ireland, 1994, p.33).

Irish legends: ‘The legends ... represented the imagination of the country; they are the kind of history which a nation desire to possess. They have a value far beyond the tale of actual events and daily recorded facts.’ (O’Grady, in History of Ireland, The Heroic Period; George J Watson, ‘Celticism and the Annulment of History’, [?], Winter 1994/5, pp.2-6.)

Diarmuid and Grainne (in trans. of W. B. Yeats and George Moore): ‘This story is only one out thousands of stories about the great, noble and generous Finn - the greatest, the noblest, and perhaps the most typical Irishman that every lived - the one story, I say, out of them all in whic the fameof the hero and the prophert is sullied and his character aspersed. (O’Grady, in The All Ireland Review; quoted in Jacqueline Genet & Richard [Cave], Perspectives in Irish Drama and Theatre, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 1991, p.1.)

[ top ]

The Anglo-Irish (1) - Standish O’Grady, memoir of an Ascendancy education: ‘At school and in Trinity College I was an industrious lad and worked through curriculums with abundant energy and some success; yet in the curriculums never read one word about Irish history and legend, nor even heard one word about these things from my pastors and masters. When I was twenty-three years of age, had anyone told me – as later on a professor of Dublin University actually did – that Brian Boromh [Boru] was a mythical character, I would have believed him. I knew nothing about our past, not through my own fault, for I was willing enough to learn anything set before me, but owing to the stupid education system of the country. (Quoted in W. Thompson, Imagination of a Revolution, p.20; quoted in Maria Tymoczko, The Irish Ulysses, California UP 1994, p.223.)

The Anglo-Irish (2):‘ As I write, the Protestant Anglo-Irish, who once owned all Ireland from the centre to the sea, is rotting from the land in the most dismal farce-tragedy of all time, without one brave deed, without one brave word. [...] [Unless they] reshape themselves in a heroic mould there would be anarchy and civil war, which might end in a shabby, sordid Irish Republic, ruled by [knavish,] corrupt politicians and the ignoble rich.’ (Quoted in Hubert Butler, ‘The Deserted Sun Palace’, in Escape from the Anthill, Lilliput 1985; also in Geoffrey Wheatcroft, reviewing In the Land of Nod, 1996, in Times Literary Supplement, 18 June 1996, pp.13-14, and in William J. Smith, ‘A Plurality of Irelands’, in In Search of Ireland, ed. Brian Graham, 1997, p.38.)

The Anglo-Irish (3): ‘... bad as you are, you are still the best class we have [and so far better than the rest that there is none fit to mention as the next best]. You are individually brave and honourable men and do not deserve the door which even the blindest can see see approaching ... You are hated to an extent you can only dimly conceive. The nation is united against you. In your hands the Irish nation once lay like soft wax ready to take any impression you chose and out of it you have moulded a Frankenstein which will destroy you.” Further: ‘Christ save us all! You read nothing, you know nothing. You are totally resourceless and stupid ... England has kept you like Strasbourg geese ...’. (Do., quoted in Hubert Butler, The Subprefect Should Have Held His Tongue, Lilliput 1990; also in P. J. Kavanagh, Voices in Ireland, Murray 1994, p.157, and [more briefly] in Declan Kiberd, Inventing Ireland, Cape 1995, p.24, citing Selected Essays and Passages, Dublin 1918, pp.180ff.)

The Anglo-Irish (4): ‘Aristocracies come and go like the waves of the sea; and some fall nobly and others ignobly. As I write, this Protestant Anglo-Irish aristocracy which, once owned all Ireland from the centre to the sea, is rotting from the land in the most dismal farce-tragedy of all time, without one brave deed, without one brave word. Our last Irish aristocracy was Catholic, intensely and fanatically Royalist and Cavalier, and compounded of elements which were Norman-Irish and Milesian-Irish [...]. Who laments the destruction of our present Anglo-Irish aristocracy? Perhaps in Ireland not one. they fall from the land while innumerable eyes are dry, and their fall will not be bewailed in one piteous dirge or one mournful melody.’ (All Ireland Review, 24 March 1900; quoted in W. J. McCormack, From Burke to Beckett, Cork UP 1985; rep. 1994, pp.180-81; also cited [in slightly less extended form] in J. C. M. Nolan, ‘Standish James O’Grady’s Cultural Nationalism’, Irish Studies Review, Dec. 1999, pp.348-49).

[ top ]

References

Justin McCarthy, gen. ed., Irish Literature (Washington: University of America 1904) selects an extract from preface to Pacata Hibernia [1896]; History of Ireland; and The Coming of Cuchulain; also ‘Lough Bray’, and ‘I give my heart to thee’.

John Cooke, ed., Dublin Book of Irish Verse 1728-1909 (Dublin: Hodges, Figgis 1909); (1846- ), cites poetry: ‘I give my Heart to Thee’ [‘... O mother-land, / I, if noe else, recall the sacred womb ... the loving eyes ... father-land ... ideal land ...’]; ‘Lough Bray’.

Stephen Brown, Ireland in Fiction (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), lists History of Ireland, The Heroic Period, 2 vols. (London: Sampson Low, Searle, Marston & Rivington; Dublin: E. Ponsonby 1878), xxii+267pp. & 348pp.; History of Ireland, Critical and Philosophical(London: Sampson Low; Dublin: E. Ponsonby 1881) [refers in preface to ‘the books already published by me [as] portions of a work in which I propose to tell the History of Ireland through the medium of tales, epic or romantic’]; Red Hugh’s Captivity (1889), being and early ed. of The Flight of the Eagle; Finn and His Companions ill. Jack B. Yeats (1892), of which Pt. IV is ‘The Coming of Finn’; The Bog of Stars [and other stories and sketches of Elizabethan Ireland] (Fisher Unwin, New Irish Library 1893), nine stories; The Coming of Cuchulainn (Methuen 1894), pp.160; The Gates of the North (1908), sequel to preceding; Lost on Dhu Corrig (1894), for boys; The Chain of Gold (1895), west coast setting, for boys; Ulrick the Ready or, The Chieftains’ Last Rally (London: Downey 1896; new edn. 1908), Battle of Kinsale; In the Wake of King James (London: Dent [1896], new ed. Wayfarers’ 1917), no historical incidents; The Flight of the Eagle ([London: Lawrence & Bullen 1897]; new ed. Dublin: Sealy, Bryers; NY: Benziger 1908), based on ‘the Annals, ... O’Sullivan Beare ... O’Clery’s Life of Hugh Roe ... and Calendar of State Papers from 1587’; also, Standish O’Grady, Selected Essays (1918).

Desmond Clarke, Ireland in Fiction [Pt II] (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1985), adds The Departure of Dermot (1917) [noticed as a ‘tiny pamphlet’ in IF1]; The Triumph and Passing of Cuchulainn [1920].

Henry Boylan, Dictionary of Irish Biography (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1988), makes mention of the influence of O’Curry’s Manners and Customs (1873) [prob. err.]

D. J. Doherty & J. E. Hickey, A Chronology of Irish History since 1500 (Gill & Macmillan 1989), cite O’Grady in connection with the influence of John O’Donovan.

John Sutherland, The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction (Harlow: Longmans 1988); notes that his stories Elizabethan Ireland [and more so of] Irish heroic ... had strong influence on the literary revival of the 1890s. He also wrote science fiction under pseudonym Luke Netterville, e.g., The Queen of the World (1900). BL 13.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 1, pp. xxiv; also unique ref. at 1053 in regard to the resort to the spurious, fake, reductive, &c. Vol. 2 selects History of Ireland, Vol I; Vol II; Toryism and the Tory Democracy [pp.521-26]; with references and notes at pp.9, 55, 120 [fumed at landlords’ incapacity to receive nationalist doctrine, ed. Deane], pp.517 [an ancient Ireland, heroic and self-sacrificingly magnificent, FDA ed. Terence Brown], 518 [genuinely patriotic publishing activity, ibid.]; 823 [Yeats, ‘Beautiful Lofty Things’, ‘Standish O’Grady supporting himself between the tables/Speaking to a drunken audience high nonsensical words ..’], 973 [cited by Rolleston], 999 [cited by Frederick Ryan], 1218 [?biogs]. BIOG., 559, ed. TCD, practised law; his discovery of Irish history and literature (he chanced upon Sylvester O’Halloran’s an Introduction to the Study of History and Antiquities of Ireland) led to his lifelong enthusiasm; a staunch Unionist, and an admirer of Carlyle, he laboured to remind landlords of their duties as leaders; ed. The All-Ireland Review, 1900-1906, presenting a radical-conservative view of politics and social life [biog. note]. See also FDA3 Index: O’Grady, Standish, 248 [facetious ref. in Beckett’s ‘Recent Irish Poetry’, 1934]; 411 [stance on landlords compared with Birmingham’s]; 548 [Hubert Butler’s mother, ‘When O’Grady and Otway Cuffe gave that Irish play at Sheestown the crowd all strolled out from Kilkenny and pulled up all the shrubs and broke the tea-cups’]; further remarks at 557, 609, 912, 693.

Library catalogues

Belfast Public Library holds The Bog of Stars (1893); Bog of Stars and other stories (1843); Chain of Gold (n.d.); The Coming of Cuculain (1894); The Departure of Dermot (1917); Early Bardic Literature of Ireland (1879); Finn and His Companions (n.d.); The Flight of the Eagle (1944); History of Ireland, 2 vols. (1878, 1881); Hugh Roe O’Donnell (1902); In the Gates of the North (n.d.); In the Wake of King James (n.d.); Lost on Du-Corrig (1944); Red Hugh’s Captivity (1889); Story of Ireland (1894); Triumph of the Passing of Cuculain (n.d.); Ulrick the Ready (1944).

University of Ulster Library, Morris Collection holds The Bog of Stars and other stories, and sketches of Eliz. Ireland (1893); The Coming of Cuchulain (1894, c.1930); Finn and His Companions (1921); The Flight of the Eagle (1897); History of Ireland, critical and philosophical (1881); In the Gates of the North (1901, c.1930); The Triumph and Passing of Cuchulain (1919); Ulrick the Ready (c.1930); Selected Essays and Passages (Talbot 1918) 340p.

[ top ]

Notes

Ulrick the Ready (1899) - The thrust of the novel is that fanatical sectarians refuse a tolerant Protestant monarchy - such as the repulsive Jesuit James Archer who goes about ‘sowing the seed ... that springs up as armed men’ [84]. O’Grady characterises Carew - not untenderly - as a master administrator and an adventurous artillery chief, but also as ‘an evil imagination nourished by an ill conscience’. Carew is accredited with the scheme to assassinate the Earl of Desmond (Red Hugh O’Donnell) after 1603. O’Grady characterises Pacata Hibernia as ‘the most famous of the Anglo-Irish historical classics.’ [181] and cites Spenser’s view of Cork: ‘The pleasant Lee that like an island fair / Encloseth Cork with his divided flood.’ According to O’Grady the Irish cloak was learnt from an earlier generation of English nobility: ‘The Great Ric[h]ard Plantagenet of York, and his heroic sons Edward, George and Richard, and the boy called Rutland, taught us to dress so.’ He acknowledges that Mountjoy authorised the slaughter of non-combatants [155; i.e., Smerick?].

The Yeats-Moore version of Diarmuid and Grania was attacked by Standish O’Grady as a ‘heartless piece of vandalism on a great Irish story’ (‘The Story of Diarmuid and Grania’, in All Ireland Review, Oct. 1901, p.244; quoted in Thomas W. Flannery, Yeats and the Idea of the Irish Theatre, 1976, p.165.)

William Irwin Thompson, The Imagination of an Insurrection, Dublin, Easter 1916, A Study of an Ideological Movement (NY: Harper Colophon 1967), takes as its point of departure George Russell’s remark that O’Grady’s books ‘contributed the first spark of ignition to the rising.’ (See James Cahalan, Great Hatred, Little Room, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1983, p.72.)

F. S. L. Lyons : In Culture and Anarchy in Ireland (1979), Lyons focuses on O’Grady as a figure of Anglo-Irish society attempting a rapprochement with the independent Ireland looming in the future - a choice which inspired Yeats, according to Roy Foster in Paddy and Mr Punch (1993), p.34.

Kith & kin: see pamphlet entitled The Gross Abuses of Public Charities Pointed Out, and the necessity for the interference of the legislature demonstrated [by] A barrister [i.e. Standish Grove O’Grady; 1815-1891] (London: O. Richards, 1846) is bound with others by authors such as Edward Davies Davenport (1779-1847) in a volume donated to Victoria and Albert Museums by John Foster. (See COPAC.)

[ top ]