| ?1875-1918 [vars. 1878; Séamus]; b. Loughrea, Co. Galway; ed. locally; journalist, ed. Southern Star, while the youngest editor of his day; also ed. The Leinster Leader, the Dublin Saturday Evening Post, and The Sunday Freeman; issued plays, The Shuiler’s Child (1909), The Parnellite (1919), Meadowsweet (1912), The Bribe (1913), which were all staged at the Abbey; others incl. The Matchmakers (1907); The Flame of the Heather (1908), revised as The Stranger; The Home Coming (1910); Lustre (1913); Driftwood (1915); he was a friend of Arthur Griffith, he assisted on the Sinn Féin paper Nationality, 1916; novels incl. The Lady of Deerpark (1917), a big house novel, and Wet Clay (1922), in which an idealistic American, returning to claim his inheritance in Ireland, is murdered by the family; |

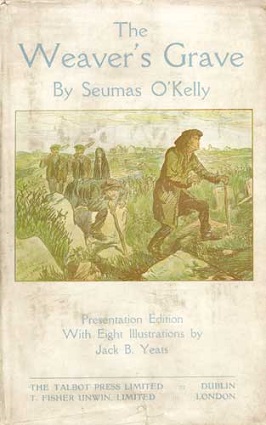

| his short fiction incl. “The Weaver’s Grave”, much-anthologised novella, regarded by some as the most perfect Irish short story; also “The Derelict”; “The Building”; collections are By the Stream of Kilmeen (1906); Waysiders (1917); The Leprachaun of Kilmeen (1920); he served as editor on Nationality while Griffith was in prison and died of a heart attack on duty there when the premisses at Harcourt St. were raided by returning soldiers, Trinity students, and ‘separation women’ [soldiers’ wives] during riotous celebrations on 14 Nov. 1918, three days after Armistice; bur. in Glasnevin with an IRA contingent; P. S. O’Hegarty prepared a bibliography in 1934 (‘he died for Ireland as surely as if he had been shot by a Black and Tan’); several works by O’Kelly, ex libris John Quinn, are held in the Berg Collection of the New York Pubic Library; James Joyce held a copy of The Weaver’s Grave in his Paris Library (ed. Connolly, 1953.) . IF NCBE DIB DIW DIH DIL MAX JIL FDA OCIL |

|

|

[ top ]

Works| Plays |

|

| Poetry |

|

| Novels |

|

“The Weaver’s Grave” [novella] |

|

|

| Short fiction (collections) |

|

| Reprints |

|

Translations |

|

|

|

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

Bibliography: S. O’Hegarty, ‘Bibliography of Seumas O’Kelly’, in Dublin Magazine, 9: 4 [1924]; rep. as Bibliography of Seumas O’Kelly (Dublin: Alex Thom 1934) [with others of Thomas MacDonagh and a.n.other]; see also issues Dublin Magazine, 10: 3; 11: 1: 12: 4; 25: 2 (cited in Rudi Holzapfel, “Bibliography of Dublin Magazine”).

[ top ]

Commentary

James Joyce (on reading By the Streams of Kilmeen): ‘The stories I have read were about beautiful pure faithful Connecht girls and lithe, broad-shouldered open-faced Connact men, and I read them without blinking, patiently trying to see whether the writer was trying to express something he had understood. I always conclude by saying to myself without anger something like this “Well there’s no doubt they are very romantic young people; at first they come as a relief, then they tire. Maybe, begod, people like that are to be found by the stream of Kilmeen only none of them has ever come under my observation, as the deceased chap in Norway remarked.”’ (Letters to Stanislaus; quoted in Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, 1959; !965 Edn., p.243.)

|

Richard Kain, Dublin in the Age of William Butler Yeats and James Joyce (Oklahoma UP 1962; Newton Abbot: David Charles 1972): ‘There is the strangely macabre humor of Seumas O’Kelly’s long story The Weaver’s Grave (1919), a minor masterpiece of mingled pathos and comedy in which two aged men stumble through an ill-kept graveyard in search of a burial place. As they mumble to themselves and argue with each other, the grotesquerie of the human condition is made apparent - and also, in an odd way, something of its grandeur. Here peasant humor is deepened into a realization of the state in which all, rich and poor, educated or rustic, meet at last on the same level. What might have been a sentimental episode becomes, in O’Kelly’s skillful telling, a tragically moving tale. One is reminded of the humanity displayed in many of the pictures of common life by Jack Butler Yeats. In both painter and storyteller, humor and humanity meet to form a poignant expression of mood, and it was natural that Yeats was chosen [163] to illustrate an edition of O’Kelly’s story, just as he had earlier illustrated Synge’s sketches of The Aran Islands.’ (pp.163-64.)

David Norris, ‘Imaginative Response versus Authority: A Theme of the Anglo-Irish Short Story’, in Terence Brown & Rafroidi, eds., The Irish Short Story (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1979): ‘The atmosphere of Seumas O’Kelly’s “The Weaver’s Grave” [Dublin: Alan Figgis 1965] is less representational than that of [Padraic] O’Conaire’s tales, its truths poetic and symbolic rather than social [...] The subject is close to the universal “why” of F. M. Forster’s A Room with a View, and for O’Kelly, as for old Mr. Emmerson in that novel, “By the side of the everlasting Why there is a Yes, a transitory Yes if you like, but a Yes”. O’Kelly’s treatment is on the whole the more successful, relying for its resolution upon the acceptance by the central characters of a world in which the only reality is subjective [52; ...] O’Kelly employs a stylistically pleasing consistence of tone and imagery. / The subsidiary characters of a “The Weaver’s Grave” are stylized, almost emblematic figures. Meehaul Lynskey, the nail-maker, has a chinkling ring to his name, a warped body, small sharp eyes and the spiritual horizons of a nail-making machine. Cahir Bowes, heavy and stony as his name and occupation, has keen grey eyes, glint-like as the mountains of stone he has broken, and a view of life also constricted by his former occupation. The repetitious blows of age have reduced these two old men to ciphers, but years alone cannot dim Malachi Roohan whose spirit of nihilism, wonderful but terrible in its honesty, blasts away cant, caution and pretence - “One flash of the eyelids and everything in this world is gone ... The world is only a dream, and a dream is nothing at all! We all want to waken up out of the great nothingness of this world.” / “And, please God, we will”, said Nan. / - You can tell all the world from me n, said the cooper, that it won’t.” / “And why won’t we, Father?” / “Because”, said the old man, “we ourselves are the dream. When we’re over the dream is over with us. That’s why”. / The bleakness of the old man’s prophecy seems to operate subliminally on the widow, wakening her to experience like a frosty disintegration of the soil that allows new growth. The fiery beauty of the evening star may call forth only paltriness from the withered heart of Meehaul Lynskey, but the widow has already begun to personalize the human beauty of one of the twin gravediggers. Their handsomeness had earlier seemed dulled by its repetition, but now the star shines like a love token over the head of the man she has silently chosen. By the end of the story even the digging of a grave has taken on a quality of youth and joy, as the widow responds to the lilt of human love, passionate but transitory - “The earth sang up out of the ground, dark and [53] rich in colour, gleaming like gold in the deepening twilight of the place.’ (p.52-54)

D. E. S. Maxwell, Modern Irish Drama (1984), The Matchmakers (Dublin: M. H. Gill 1908); The Shuiler’s Child, with Thomas MacDonagh, When the Dawn is Come (Dublin: Maunsel 1908); Meadowsweet (Talbot n.d.).

Alexander G. Gonzalez: ‘Seumas O’Kelly and James Joyce’, in Eire-Ireland, 21, 3 (Sept. 1986), on interior monologue in The Lady of Deerpark: ‘Joyce’s shadow is clearly evident here, for not a single published account of Irish literary history acknowledges the fact that more than one Irihsman experimented with the technique during these years.’ (p.93; quoted in James Cahalan, op. cit. [infra], 1988, p.125.)

James Cahalan, The Irish Novel (Boston: Twayne Publ. 1988): ‘The Big House setting of Seumas O’Kelly’s The Lady of Deerpark is a thin frame for a melodramatic, forgettable plot rather than the powerful, personal emblem that it was for Somerville and Ross. It indicates both the prevalene of the Big House tradition and the fact that non-Ascendancy writers such as O’Kelly could not successfully enter it; he is far better writing about the gritty peasants of “The Weaver’s Grave”. It is interesting, though, that O’Kelly experiments a bit with interior monologue in The Lady of the Deerpark, and his narrator Paul Jennings - like Jason Quirk, a narator capable of referring to the Greeks and Turgenev - has a Joycean notion of epiphany, “There are moments in the lives of men that are as flashlights, tense moments when innate things are revealed to us.”’ (p.125.) Further, notes that Alexander Gonzalez detects the possible influence of Eduard Dujardin on O’Kelly’s use of interior monologue [as supra].

James H. Murphy, Catholic Fiction and Social Reality in Ireland, 1873-1922 (Conn: Greenwood Press 1997): ‘The forthright anger of those who find freedom by rejecting Catholic Ireland turns to a helpless bitterness in those who are not only pessimistic about the possibility of creating a new Ireland but are also apathetic about the worth of theindividual’s inveighing against it. Seumas O’Kelly’s novels, The Lady of Deerpark (1917) and Wet Clay (1922) are written in a style of bleak realism. They recount the destructive power of the greed of people immersed in the ethos of Catholic Ireland. In the former, one such character exploits the vulnerability of gentry illusions, while, in the latter, a whole community destroys the idealism of a young man who has returned to Ireland with a mission to help save and improve the country. No individual even escapes into freedom in these novels.’ (p.133.)

[ top ]

Frank McNally, ‘Last Post – Frank McNally on Seumas O’Kelly, writer, journalist, and victim of the 1918 Armistice’ |

|

Among his many other distinctions, the writer and journalist Seumas O’Kelly (circa 1880-1918) was one of the few Irish people who could be said to have been a victim of both the Troubles and the first World War. He wasn’t a combatant in either, exactly. But of the manner of his premature passing, 100 years ago next month, one admirer later commented: “He died for Ireland as surely and as finely as if he had been shot by a Black and Tan”. On the other hand, the events that killed him were a direct result of the 1918 Armistice, making him also, arguably, one of the last casualties of the Great War. Aged only 38, but weakened by rheumatic fever and a heart condition, O’Kelly had been working as usual that November day, deputy-editing the Sinn Féin newspaper Nationality in place of Arthur Griffith, in jail in England. Meanwhile, Dublin’s loyalists were celebrating, some of them riotously. Amid the union jacks flying everywhere, the tricolour on Sinn Féin’s offices was considered a provocation. So a group of off-duty soldiers, Trinity students, and “separation women” - so-called because of the Separation Allowance that supplemented whatever their army husbands sent home - stormed the building. Harry Boland, who was also there, turned a hose on them, while the editor defended himself with the walking stick to which he had been reduced. Alas, O’Kelly suffered either a cerebral haemorrhage or heart attack - accounts differ - or both. Whatever it was, he never recovered. His funeral in Glasnevin became a show of force by republicans, to whom he was now a martyr. As PS O’Hegarty, author of the “Black and Tan” comment, put it: “He died at his post.” Born in Loughrea, O’Kelly was a prolific writer throughout his short life, much of which he spent in newspapers. During a spell at the Southern Star, he was Ireland’s youngest editor. He later also edited the Leinster Leader, Saturday Evening Post, and (very briefly) Sunday Freeman. In between all that, he wrote plays, poetry, novels, and short stories too. His first story collection attracted the notice - albeit sarcastic - of James Joyce, who had shared a class with him in UCD and complained that O’Kelly’s characters were all “beautiful, pure faithful Connacht girls and lithe, broad-shouldered open-faced young Connacht men”. Happily, Joyce recovered from his early distaste to admire O’Kelly’s more mature work. As a playwright, O’Kelly wrote for the Theatre of Ireland, a kind of anti-Abbey, for which his The Shuiler’s Child was a big success in 1909. Socialist and feminist in outlook, the play centred on the adoption of a workhouse child and featured a famous performance by Máire Nic Shiubhlaigh as the mother, although The Irish Times also noted that the role of would-be adopter was “very well and amusingly filled” by one Countess Markievicz. O’Kelly’s specialty was recording everyday speech, particular as spoken in his native Galway. Another writer from that county, Lady Gregory had been less successful at capturing what Yeats called “that beautiful English of the country people who remember too much Irish to talk like a newspaper”. She was mocked for inventing her own language: “Kiltartanese”. O’Kelly, by contrast, had a finely-tuned ear. What is now considered his finest work was a novella unpublished in his lifetime. The Weaver’s Grave (1919) is the story of a widow and two elderly gravediggers who stumble through a decrepit cemetery in search of the widow’s husband’s grave. As one critic said: “What might have been a sentimental episode becomes, in O’Kelly’s skillful telling, a tragically moving tale.” It was for the likes of this that, in 1971, O’Kelly was described by another literary commentator as “Ireland’s most neglected genius”. But if he was neglected then, the situation has not improved much in the intervening half century. He’s all but forgotten now. He will no doubt be recalled next month in the pages of the Leinster Leader, which despite illness, he returned to edit after the 1916 Rising when his brother Michael, who had succeeded him in the job, was interned. As for more formal commemorations, I’m not aware of any yet. Neither is P. J. Lawlor, who wrote to me urging a mention for O’Kelly in the run-up to his anniversary. As PJ noted, his actual centenary is likely to be overshadowed by the centenary of the armistice that led indirectly to O’Kelly’s demise. Hence this slightly early memorial to a man who was either one of the last victims of the war, or one of the first victims of the peace. |

| The Irish Times (18 Oct. 2018) - available online; accessed 30.05.2019). |

[ top ]

“The Weaver’s Grave” [Pt. III]:The widow went up the road, and beyond it struck the first of the houses of the near-by town. She passed through faded streets in her quiet gait, moderately grief-stricken at the death of her weaver. She had been his fourth wife, and the widowhoods of fourth wives have not the rich abandon, the great emotional cataclysm, of first, or even second, widowhoods. It is a little chastened in its poignancy. The widow had a nice feeling that it would be out of place to give way to any of the characteristic manifestations of normal widowhood. She shrank from drawing attention to the fact that she had been a fourth wife. People’s memories become so extraordinarily acute to family history in times of death! The widow did not care to come in as a sort of dramatic surprise in the gossip of the people about the weaver’s life. She had heard snatches of such gossip at the wake the night before. She was beginning to understand why people love wakes and the intimate personalities of wakehouses. People listen to, remember, and believe what they hear at wakes. It is more precious to them than anything they ever hear in school, church, or playhouse. It is hardly because they get certain entertainment at the wake. It is more because the wake is a grand review of family ghosts. There one hears all the stories, the little flattering touches, the little unflattering bitternesses, the traditions, the astonishing records, of the clans. The woman with a memory speaking to the company from a chair beside a laid-out corpse carries more authority than the bishop allocuting from his chair. The wake is realism. The widow had heard a great deal at the wake about the clan of the weavers, and noted, without expressing any emotion, that she had come into the story not like other women, for anything personal to her own womanhood - for beauty, or high spirit, or temper, or faithfulness, or unfaithfulness - but simply because she was a fourth wife, a kind of curiosity, the back-wash of Mortimer Hehir’s romances. The widow felt a remote sense of injustice in all this. She had said to herself that widows who had, been fourth wives deserved more sympathy than widows who had been first wives, for the simple reason that fourth widows had never been, and could never be, first wives! The thought confused her a, little, and she did not pursue it, instinctively feeling that if she did accept the conventional view of her condition she would only crystallise her widowhood into a grievance that nobody would try to understand, and which would, accordingly, be merely useless. And what was the good of it, anyhow? The widow smoothed her dark hair on each side of her head under her shawl. |

Further: ‘The two old men wandered about Cloon na Morav, in no hurry whatever to get through with their business. After all they had had a long time pensioned off, forgotten, neglected, by the world. The renewed sensation of usefulness was precious to them. They knew that when this business was over they were not likely to be request for anything in this world again. They were ready to oblige the world, but the world would have to allow them their own time. The world, made up of the two grave-diggers and the widow of weaver, gathered all this without any vocal proclamation. Slowly, mechanically as it were, they followed the two ancients about Cloon na Morav. And the two ancients wandered about with the labour of age and the hearts of children. They separated, wandered about silently as if they were picking up old acquaintances, stumbling upon forgotten things, gathering up the threads of days that were over, reviving their memories, and then drew together beginning to talk slowly, almost casually, and all their talk was of the dead, of the people who lay in the ground about them. They warmed to it, airing their knowledge, calling up names a complications of family relationships, telling stories, reviving virtues, whispering at past vices, past vices that did not sound like vices at all, for the long years are great mitigators and run in splendid harness with the coyest of all the virtues, Charity.’ (Excerpt on Facebook given by Patrick Neil Doherty [30.05.2019].) |

| [For full text, see RICORSO Library, “Classic Irish Texts” - infra; see also under Notes - infra.] |

[ top ]

References

Stephen Brown, Ireland in Fiction: A Guide to Irish Novels, Tales, Romances and Folklore [Pt. I] (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), lists By the Stream of Kilmeen [c.1910]; The Lady of Deerpark (1917); Waysiders, front. by Michael Willmore [i.e., Mícheál MacLiammóir]. IF states b.1881 [?err.]

Desmond Clarke, Ireland in Fiction: A Guide to Irish Novels, Tales, Romances and Folklore [Pt. 2] (Cork: Royal Carbery 1985), adds The Leprachaun of Killmeen [sic] [c.1919]; The Golden Barque and the Weaver’s Grave; Hillsiders; Wet Clay.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2; selects from Waysiders, “The Building” [1093-110]; 1219, WORKS & CRIT adds The Land of Loneliness and Other Stories, sel. with intro. by Eamon Grennan (Gill & Macmillan 1969); Anne Clune, ‘Seumas O’Kelly’ in P. Rafroidi & Terence Brown eds, The Irish Short Story (Gerrards Cross 1979); A. Martin, The Genius of Irish Prose (Cork 1985); J. W. Foster, Fictions of the Irish Literary Revival (Gill & Macmillan; Syracuse UP 1987).

David Marcus, ed., Irish Short Stories (Cork: Mercier rep. 1976), gives selection, 91pp.

Helena Sheehan, Irish Television Drama (1987), lists RTE Film, The Weaver’s Grave, Seumas O’Kelly/dir. Christopher FitzSimon, adapted Michael Ó hAodha (1963) [108].

Hyland Books (Cat. 224) lists Meadowsweet (n.d.); Ranns and Ballads (Dun Laoghaire ?1969).

Belfast Public Library holds The Bribe (1914, 1952); Golden Barque and Weaver’s Grave (1919); Hillsiders (1921); The Lady of Deer Park (n.d.); Meadowsweet (n.d.); Ranns and Ballads (n.d.); Waysiders (1917); Wet Clay (1922).

[ top ]

Notes

Forrest Reid: Reid wrote of O’Kelly, ‘the effect of his finest stories is infinitely richer than the sum of their recorded happenings.’ (Retrospective Adventures, 1942; quoted in George Brandon Saul, ‘Seumas O’Kelly’, in Robert Hogan, ed., Dictionary of Irish Literature, 1979) Note: A copy of Reid’s Following Darkness (Arnol 1912) was held in O’Kelly’s library [COPAC - online]

Father Paddy Browne, ed., Aftermath of Easter Week (1917), includes a poem by Seumas O’Kelly on 1916, with the lines, ‘England had bullet and burning lime / And Ireland has names that march with time.’ (“The Seanachie Tells Another Story”).

Seumas O’Sullivan, The Rosses and Other Poems (Dublin & London: Maunsel & Co. 1918) - is dedicated to Seumas O’Kelly.

Sigmund Freud: re the grave-digger twins in “The Weaver’s Grave”: ‘[the] doubling, dividing and interchanging of the self [situates twins as] a thing of terror’ (From ‘The Uncanny’, rep. in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, ed. Vincent C. Leitch, London: Norton 2001, p.940; quoted in Joanne Watkiss, ‘Ghosts in the Head: Mourning, Memory and Derridean “Trace” in John Banville’s The Sea’, in The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies, 2 (March 2007) [online; 21.11.2007].

[ top ]