Life

| 1916-77 [Seán Padraig Ó Riordáin; angl. & fam. Jackie Riordan]; b. 3 Dec. 1916, in Baile Mhúirne [Ballyvourney], Co. Cork; son of namesake [Gl.] and Mairéad n[ée] Ní Loineacháin; ed. CBS, North Monastery, Cork city; lost his father to TB at 10; moved to Inniscarra at 15; contracted TB and was sent to a sanitorium - a life-shaping experience; settled in extension to family home and embarked on literary career commenced with poems in hospital; became a literary early follower and a later reviler of Daniel Corkery’s ‘hidden Ireland’ revivalism; |

|

worked as clerical officer (for motor taxation) in the City Hall, Cork during thirty years from 1936 [aetat. 1926]; took early retirement in 1965; his first poems appeared in Comhar (est. 1942); issued Eireaball Spideoíge (1952), a controversial collection at that period in the introduction to which he identified ‘uaigneas’ [‘loneliness’] as one of the preconditions for poetry; criticised by Máire Mhac an tSaoi for poor grasp of traditional language and unintelligible to those who didn’t know English and English tradition also; his poem “Fill Arís” celebrates the Irish of Dun Chaoin and recurs to Irish culture ‘before the battle of Kinsale was lost’ [Ó buaileadh Cath Chionn tSáile"]; |

| contrib. a weekly column to The Irish Times, 1967-1975 [var. 1969 to 1976]; kept a diary from 1940, recording his ‘fight against death’ [frm TB]; worked as part-time assistant in Dept. of Irish [Gaeilge] at UCC in the early 1970s; wrote a Saturday column for Gageby in The Irish Times, writing widely on literature and society - often in acerbic terms; awarded DLitt. (NUI), 1976; retained life-long friendship with his brother Tadhg who lived in Mayfield, in Cork City’s northside; latterly lived in Sarfield Court [Block 8, Floor 2], where he was visited by a nurse, suffering increasingly from respiratory illness; |

| remained religious and was anointed with extreme unction, but denied he was a Catholic in his latter diary entries; d., 21 Feb. 1977, in Cork; bur. St. Gobnait’s Church, Ballyvourney, Co. Cork; his collection Tar Éis Mo Bháis (1967) was reissued posthum. in 1978; his funeral oration was given by Cathal Ó Dálaigh, President of Ireland; Collected Poems, 1986-2006 (2006); a series of essays in appreciation of the poet was broadcast on Radio na Gaeltachta in 2007 and TG4 documentary on his life was broadcast on 23 Jan. 2008 [dated 2007; pub. on internet 10 July 2013]; |

| Seán Ó Ríordáin: Na Dánta (2011) was edited and introduced by Seán Ó Coileáin and launched by Liam de Paor in the O’Rahilly Building, Univ. of Cork, 8 Dec. 2011; the house where Ó Riordáin lived in Iniscarra is in ruins; his use of Irish called ‘Riordainesque’ by Liam de Paor; his diaries - long held at UCD - were edited by Tadhg Ó Dúshláine as Anamlón Bliana (Cló Iar-Chonnacht), June 2014; a conference on Ó Ríordáin of 2016 has been edited by Tríona Ní Shíocháin & Ríona Ní Churtáin (Sagart, 2018). DIW FDA OCIL |

|

| Seán Ó Riordáin (1916-77) |

[ top ]

Works| Poetry |

|

| In translation |

|

| Diaries |

|

| [ top ] |

| Miscellaneous |

|

[ top ]

Criticism

|

| [ top ] |

See Mise Seán Ó Riordáin, a tribute documentary introduced by Louis de Paor (TG4, 10 July 2013) - with Liam Ó Muirthile, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Rita Ann Higgins, Greg Delanty, Máire Mac an tSaoi, Alan Titley, et al. [available on Youtube - online; accessed 23.10.2014].

Note: The documentary [Mise Seán Ó Riordáin] traces his life with much emphasis on his isolation both as a victim of tuberculosis in days when the disease was regarded as a stigma and also in his position as a bilingual speaker and writer whose first exposure was to the English of his mother which dominated the household. The programme ends with a close account of his last days, based on his diary, and interviews with the children of his brother Tadhg who remember him with affection but also for a certain remoteness which is shattered by de Paor’s revelation that, in his diary, he speaks of them as “the people he loves most of all”, comparing their honesty and directness to that of older people. [BS; from memory; 25.12.2014.]

[ top ]

Commentary

Theo Dorgan, ‘Twentieth-century Irish Language Poetry’ [essay], in An leabhar mór/The Great Book of Gaelic: ‘Apart from [Máirtín] Ó Direáin, no poetry of true value would appear in the Irish language until Seán Ó Ríordáin published Eireaball Spideoige in 1952. Consumptive, lonely and unillusioned, Ó Ríordáin was a kind of alienated pietist whose work strikes the first truly modern note in Gaelic poetry. Refusing the succour of sentimental loyalty to the forms and tropes of the high Gaelic tradition, his agonised soul-searching is a local version of the doubt and existential anguish which now seems so characteristic of the European mid-century. But Ó Direáin’s reluctant, even angry abandoning of the Arcadian peasant dream does not quite make him modern, in the sense that Eoghan Ó Tuarisc, say, writing self-consciously under the shadow of the Bomb, is modern. [...]’ (Rep. in Archipelago [online].)

|

| President Cairbhall Ó Dálaigh at the funeral of Seán Ó Ríordáin |

[ top ]

Louis de Paor, ‘“Adhlacadh mo Mhathar” by Seán Ó Ríordáin’, in Irish University Review, Special Poetry Issue (Sept. 2009: ‘[...] It was that amalgam of native and non-native elements that drew the most severe reaction from critics when Eireaball Spideoige was first published, provoking heated debate in Irish and in English, and vehement exchanges that extended beyond the usual literary and language journals to enliven the letters pages of The Irish Times. Writing under the pseudonym “Thersites”, Thomas Woods questioned Ó Ríordáin’s linguistic credentials, arguing that he was not a native speaker of Irish and could never, therefore, ‘comprehend that instinctive feel for the connotations of words and phrases that only a native speaker can have’. Brendan Behan responded by pointing to the achievements of Samuel Beckett: “I don’t see however that Seán Ó Ríordáin, born in Baile Mhuirne, is not as well entitled to write in Irish as Samuel Beckett, born in Dublin, is to write in French. Both are friends of mine, and bedamned if I’ll make fish of one and flesh of the other”. Patrick Kavanagh defended his right to speak of Ó Ríordáin without having read him by claiming that it was generally understood that poetry in Irish was no more than “the doodling and phrase-making of mediocrities”, before dismissing out of hand the arguments of Ó Ríordáin’s publisher Seán Ó hEigeartaigh: “As Gertrude Stein would say: A poet is a poet even in his walking down a street. And judging by what Whitehead calls ‘the act of negative prehension’, I would be inclined to think that anyone Mr Ó hEigeartaigh thought a poet would be surely the opposite”. Ó hEigeartaigh’s response was both ad rem and ad hominem : “This is extremely embarrassing for both of us, because I have always thought Mr Kavanagh a poet - and not merely from having seen him walk down a street”.’ (Citing Seán Ó Coileáin, Seán Ó Ríordáin: Beatha agus Saothar, Baile Atha Cliath: An Clochomhar, 1982, pp.247-49; see full-text copy in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > Journals > IUR”, via index, or direct.)

[ top ]

Quotations

Scáthán Véarsaí: ‘Remove from your mind / The surfaces of English civilisation, / Shelley, Keats, and Shakespeare: / Return again to your kind [...]. / Make confession and make Pease with your own family tree.’ (Quoted with trans. in Declan Kiberd, ‘Anglo-Celtic Literature: Sean O Riordain’, in Irish Classics, London: Granta 2000, pp.606-16, p.615; quoted in Callum Boyle, ‘Tradition and Transgression in the Poetry of Michael Hartnett’, MA Diss., UUC, 2005, p.52.)

| “Adhlacadh mo Mháthair” | |

|

Agus d’fhan os cionn na huaighe fé mar go mb&’eol di Du thuirling aer na bhFlaitheas ar an uaigh sin, Le cumhracht bróin do folcadh m&’anam drúiseach, Tháinig na scológa le borbthorann sluasad, Grian an Mheithimh in úllghort, Ranna beaga bacacha á scríobh agam, |

| Note: There is an English line-by-line translation at the Irish Translation Forum - online; accessed 23.10.2014. A recorded version read by the poet himself can be found on various servers. On the occasion of the poem, see note - infra. | |

[ top ]

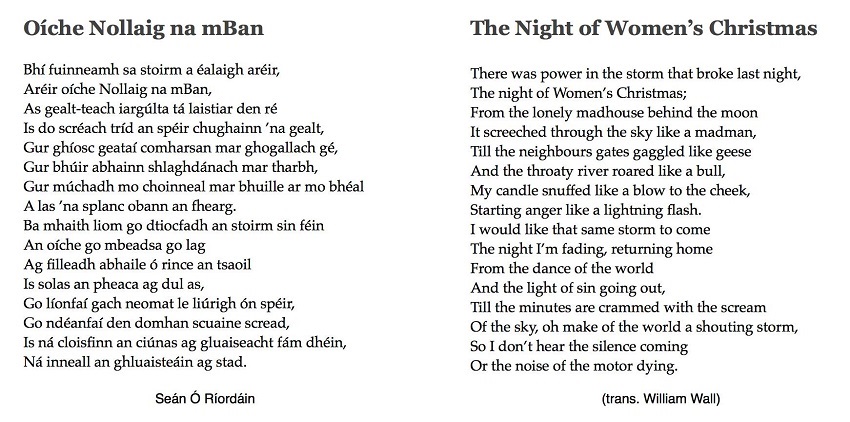

| —Posted on Facebook by William Wall [q.v.] - 12.01.2018. |

[ top ]

Dúchas & Corkery: ‘Dúirt [Daniel] Ó Corcora liom uair gan aon line a scríobh ná beadh bunaithe ar line as an seanfhilíocht. Ac cad tá le déaneamh nuair a bhíonn nithe lasmuigh den dtraidisiún dulta i nduine - nuair a bhionn an duine níos fairsinge ná an traidisiún ... Tá sé ceart go leor fanuint laistigh de thuiscint na Gaeilge ach rude eile is ea cide díot féin a fhágaint as an áireamh. Ní foláir an dúchas d’fhairsingiu da dhainséaraí é.

[Daniel] Corkery told me once not to write a single line that wasn’t based on a line of the old [Irish language] poetry. But what can one do when things outside the tradition have gone into you - when the person is wider than the tradition? It’s okay staying within the understanding of Irish but it’s something else to leave some of yourself out of the equation. Nativeness [“an dúchas”] must be broadened however danger that is.]’ (Quoted in Seán Ó Coilean, Seán Ó Riordáin: Beatha agus Saor, 1982, p.210; cited in Frank Sewell, ‘James Joyce’s Influence on Writers in Irish’, in The Reception of James Joyce in Europe, ed. Geert Lernout, et al., Thoemmes/Continuum 2004, p.477.) [See also note on Daniel Corkery, infra.]

James Joyce: ‘Mé ag léamh “Ulysses” le Joyce. Dúirt Corkery gur bhain filí na hochtú aoise déag ceol as an dteangain nár baineadh riamh roimis aisti. D’imríodh cleasanna le ceol na teangan agus do thit cith ceoil anuas orthu. Ní miste dúinne imirt le brí na bhfocal again titfidh cith bri anuas orainn. Imrimis le bri na bhfocal. Imirt focal. Joyce. [I’m reading Joyce’s Ulysses. Corkery once said that eighteenth-century [Irish] poets wrung a music out of the [Irish] language that had never been wrung out of it before. They played tricks with the music and the language and a shower of music fell down on them. As for us [modern poets in Irish], we ought to play with the meaning of words and a shower of meaning will fall on us. So let’s play with the meaning of words. Wordplay.]’ (Quoted [in English] in Ó Coilean, op. cit. , 1982, p.222; cited in Sewell, op. cit., 2004, p.478.)

[ top ]

Grattan Freyer, ed., Modern Irish Writing (1979), selects “Frozen Sea”.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3 selects from Eireaball Spideoíge; Brosna, ‘Adhlacadh Mo Mháthar’/‘My Mother’s Burial’; ‘Cúl an Tí’/‘Behind the House’; ‘Cnoc Mellerí/‘Mount Melleray’; ‘Reo’/‘Freeze; ‘Fiabhras’/‘Fever’; ‘Na Leamhain’/‘The Moths’; ‘Claustrophia’.

Patrick Crotty, ed., Modern Irish Poetry: An Anthology (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1995), selects “Adhlacadh Mo Mháthar ” [114], trans. as “My Mother’s Burial ” [115]; “Malairt ” [116]; trans. as “Switch ” [117]; “Cnoc Melleri ” [118], trans. as “Mount Melleray ” [119]; “Siollabadh ” [124]; trans. as “Syllabling ” [125]; “Claustrophobia ” [124], trans. as “Claustrophobia ” [125]; “Reo ” [126], trans. as “Frozen Stiff ” [127]; “Fiabhras ” [126]; trans. as “Fever ” [127]. (All translations by Crotty.)

[ top ]

Notes

Daniel Corkery: Ó Riordain was encouraged as an Irish writer by Daniel Corkery and wrote a moving homage to him as ‘Do Dhomhall Ó Corcora’, c.1950 (printed in Eireaball Spideoige), but later recorded sense of bitterness towards him in a diary-entry, ‘Bhiodh fíliocht a scríobh sa ghaeilge go dti gur leag Donall Ó Corcora a lamh mharbh uirthi’ [Seán Ó Riordain, Beatha agus Saothar, le Sean Ó Coileain, p.259; cited in Patrick Walsh, UUC MA thesis, 1993, p.70].

Máire Mhac an tSaoi: Mhac an tSaoi criticised Ó Ríordáin’s imperfect knowledge of Irish in her review-article on Eireaball Spideoíge, greatly injurying his pride and confidence. In 1970 she phone in during an interview on with Ó Ríordáin on RTE’s “Writer in Profile” programme to say that she ‘had never heard better Irish spoken than that by Seán Ó Ríordáin tonight’ - an apology which he rejected - later telling Seán Ó Coileáin that his ‘bowels moved in disdain’. (Quoted in Frank Sewell, A New Alhambra, Oxford 2000, p.48; cited in Wikipedia article on Ó Ríordáin.)

Women poets? His line ‘Ní file ac filíocht í an bhean’ [not poet but the subject of poetry is woman]’ is the subject of criticism by Nuala Ó Dhomhnaill in a contribution to Irish Poetry Since Kavanagh, ed. Theo Dorgan (Dublin: Four Courts 1996).

“Adhlacadh mo Mháthair”: his poem of that title was occasioned by his mother’s anxiety on hearing that he was endangered by a fire in the sanitorium.

John Montague calls Seán Ó Riordáin ‘the hermit crab of / a receding language’, in Smashing the Piano (1999). (See review by Bernard O’Donoghue, in The Irish Times, 15 Jan. 2000.)

The diaries: ‘A chara, - You carried a passionate plea by Liam O Muirthile for the publication of the diaries of Seán O’Riordáin which were written over a period of almost 40 years, from 1940 to the late 1970s (The Irish Times, 24 Feb. [2002]). / There is also another publication waiting to be compiled: his weekly column for The Irish Times from 1969 to 1976. These twin publications, revealing the private, internal life and the public commentary on the concerns of the day, respectively, would constitute a fitting tribute to the work and memory of a truly outstanding artist. The year 2002, appropriately, will mark his passing, 25 years ago. - Is mise, Dr M. W. [Liam] Ó Murchú, Bothar an Scolaire, Baile Atha Cliath [Dublin] 16.’ [Note: the diaries were edited by Tadhg Ó Dúshláine as Anamlón Bliana for Cló Iar-Chonnacht and launched in June 2014; note further: Ó Murchú died in 2015.

[ top ]