|

William Wall

Life

| 1955- [”Bill”]; b. Cork; grew up in Whitegate village; afflicted with Still’s Disease [rheumatoid arthritis] from the age of 12; ed. CBS, Middleton; grad. UCC (Philosophy & English); taught England and drama at PBS, Cork, with Cillian Murphy among his students; issued poetry collections, Mathematics (1997), winner of Patrick Kavanagh Poetry Award; wrote of Alice Falling (2000), a novel concerning an abused wife, and Minding Children (2001), a novel of child abuse; also The Map of Tenderness (2002), dealing with a mother’s journey from Huntingdon’s disease to euthanasia; shortlisted for Raymond Caver Prize, 2003; issued Fahrenheit Says Nothing To Me (2004), poems; winner of Séan O’Faolain Award, 2004; |

| |

| issued This is the Country (2005), a first-person novel about the plight of youth in Irish Corporation housing-estates today, long-listed for the Man Booker Prize and short-listed for the Hughes & Hughes National Book Award and The Young Mind Prize; issued No Paradiso (2006), stories; attended European Writers Writers' conference in Istanbul as an Irish delegate, 2010; issued poems, Ghost Estate (2011); winner of Virginia Faulkner Award, 2012 - for a novel-extract in Prairie Schooner (University of Nebraska-Lincoln); issued Hearing Voices, Seeing Things (2016), stories; directed Listowel Writers’ Week “Getting Started” workshop, May 2015; |

| |

| winner of Drue Heinz Literature Award of Pittsburgh UP, Jan. 2017; his story “The Mountain Road” was published in Granta (April 2016); married to Liz Kirwan [a mathematician], 30 June 1979, with whom two children; lives in Cork and spend some time every year in Camogli, Liguria (Italy); enrolled as a PhD candidate in Creative Writing in the School of English, UUC; issued The Islands, short stories about three sisters living pseudo-idyllic lives; winner of the Drue Heinz Literature Prize Award of Pittsburgh University; Wall maintains a strenous blog on Irish and world affairs as The Ice Moon (2006- ); a new novel, Suzy, Suzy, launched at Farmgate restaurant, Cork, April 26 2019. |

|

|

|

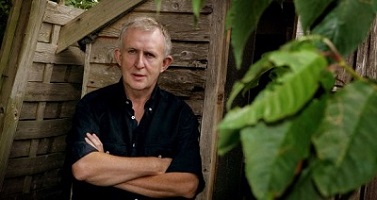

Portrait by David Sleator (The Gloss, 2017) |

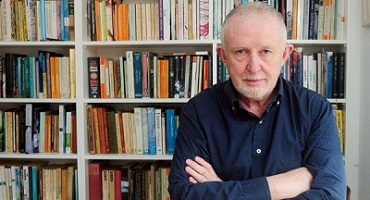

Photo by Liz Kirwan |

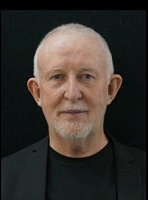

Drue Heinz Award (2017) |

| Awards and posts include .. |

The American Ireland Fund / Writers’ Week Poetry Prize (1996); the Patrick Kavanagh Award (1997), the Sean Ó Faoláin Prize (2004), the Virginia Faulkner Award (2012), and Drue Heinz Prize for Literature (2017). Fellow of the Liguria Centre for the Arts and Humanities (20090; Writer in Residence at the Princess Grace Irish Library in Monaco (2010); Irish delegate to the European Writers’ Parliament in Istanbul (in 2010); Drue Heinz Literature Award (2017). |

[ top ]

Works

| Poetry collections |

- Mathematics & Other Poems (Cork: Collins Press 1997) - see infra.

- Fahrenheit Says Nothing to Me (Dublin: Dedalus Press 2004), 86pp.

- Ghost Estate (Moher: Salmon Poetry 2011), 143pp., [1 port.]

|

| Novels |

- Alice Falling (London: Sceptre 2000), 206pp.

- Minding the Children (London: Sceptre 2001), 282pp.

- The Map of Tenderness (London: Sceptre 2002), 286pp.

- This is the Country (London: Sceptre 2005), 288pp.

- Hearing Voices, Seeing Things (Inverin: Doire Press 2016).

- The Islands (University of Pittsburg 2017).

[...]

Writers Anonymous (New Islands 2025), 264pp.

|

| Short fiction |

- No Paradiso (Brandon Press 2006), 191pp. [see contents].

|

| For children |

- The Powder Monkey: A 1798 Story (Cork: Mercier 1996).

- The Slave Coast (Cork: Mercier 1997).

- The Cove of Cork (Cork: Mercier 1998).

|

| Miscellaneous |

- contrib. to Phoenix Book of Irish Short Stories (London: Phoenix 1998).

- ‘The Mountain Road’, in Granta Magazine (19 April 2016) - see infra.

|

| Journalism |

- Q&A with William Wall, in Listowel Writers’ Week (12 March 2015) - online.

- ‘William Wall: hearing an odd remark, seeing the story’, in The Irish Times (24 June 2016) - online

- “I’ve got death certificates for the crows”, in The Irish Times (24 June 2016) s- online.

- ‘I couldn’t write same book twice and I wouldn’t want to’, interview article with Sue Leonard, in Irish Examiner (20 May 2017) [see infra].

|

[ See also his translation of “Oíche Nollaig na mBan" by Seán Ó Ríordáin - supra. ]

Bibliographical details

No Paradiso (Brandon Press 2006), 191pp. - stories [”Dionysus and the Titans”; “What Slim Boy, O Pyrrha”; “The Bestiary”; “Surrender”; “From the Hughes Banana”, “In Xanadu”; “Nero Was An Angler; “The William Walls”, &c.].

| Available copies |

- Mathematics & Other Poems (Cork: Collins Press 1997) - see copy as attached.

- ‘The Mountain Road’, in Granta: The Magazine of New Writing [Granta 135] (19 April 2016) - see copy as attached.

|

[ top ]

Commentary

| Wikpedia writes ... |

[William Wall’s] provocative political blog, The Ice Moon, has increasingly featured harsh criticism of the Irish government over their handling of the economy, as well as reviews of mainly left-wing books and movies. A lot of his posts are satirical such as “Wall Supports Brand Ireland” or “A New Proclamation” which is a satire response to Ireland’s economic crash and the EU/IMF bail-out, using the language and structure of the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic, a founding document of the state. He writes for Irish Left Review, and reviews for The Irish Times and occasionally for literary journals. His work has been translated into several languages. He has also appeared on the Irish-language channel TG4, such as in the programme Cogar. He is a longtime sufferer from Still’s disease and described his efforts to circumvent the disabling effects of the disease using speech-to-text applications as ‘a battle between me and the software’. He was one of the Irish delegates at the European Writers Conference in Istanbul in 2010.

|

[Wall’s internet blog The Ice Moon includes ...

|

School Shootings

Friday 16 February 2018

I've been thinking about school shootings. I was a teacher once, and I remember one particular young man of 17 years who had really serious anger management problems. I can remember him shouting at me in class over some trivial thing and having to bring him outside and talk him down. He didn’t hate me but he hated several of his teachers, some of them with a deep lasting hatred. He was, as we say,... |

Why I oppose paying for water

Wednesday 12 April 2017

Why do I oppose paying for drinking water?

1. Firstly I oppose the idea that if we use something we should pay for it. This is fine in a transactional relationship such as when someone buys coffee and a cake, or a car. But such a relationship between the state and the person is not appropriate. Why would a person want a state to exist? To provide her and her fellow inhabitants with certain ... |

Prison walls for a river: walling Cork City

Thursday 30 March 2017

Walling Cork: The OPW flood plan for Cork City

Cork is a beautiful and strange city. The historic centre lies between two walls of water - the North and South branches of the river Lee. Originally a marsh divided into islands, the ghosts of the dividing channels still remain, bridged over and hidden but returning to haunt the city on rising tides at certain times of the year. It’s a busy ... |

Me and pot: medical cannabis and me

Monday 16 January 2017

A hard winter of the bones

For almost 50 years now I’ve suffered from a debilitating, often crippling and painful condition called Still’s Disease, a form of Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis which strikes children. I contracted the disease at 12 years of age. When I search for an image for the condition I imagine ‘a hard winter of the bones’. Fifty years of experience with almost ... |

|

[...]

|

I discovered José Saramago

Saturday 27 May 2006

I discovered José Saramago, to my shame, only a few months ago. Now I can’t believe I lived without his humane voice in my head. Blindness was the first book of his that I came across, and it remains for me the best so far.

In a city that could be anywhere a man goes blind. His wife takes him to the doctor and subsequently the doctor goes blind. He seems to have been ‘infected’ with blindness. ... |

Manu

Sunday 7 May 2006

Driving late at night between Limerick and Cork, I see four powerful lights coming towards me. Above them, at an elevation of perhaps six feet, I see - also in lights - the word MAN. The lights draw close and I see that they represent an articulated truck.

MAN is in the cab.

It takes me some time to work out that the driver is a follower of Manchester United football club, but ... |

|

[ Available online [accessed 16.02.2018] For full listing - see attached. ]

|

[ top ]

Sue Leonard, reviewing Map of Tenderness in Books Ireland (Sept. 2002), writes: ‘The Map of Tenderness is, above all, a love story. The opening chapters featuring Joe and Suzie makes exquisite reading. But it is the lasting bo[n]ds of love that make Wall’s novel great. Scared of developing Huntingdon’s[,] Joe wants to “spare” Suzie, but she is made of sterner stuff, bringing an element of hope and strength to the novel. And over it all, there’s the enduring love of Joe’s parents [...]’.

Sue Leonard, review of This is the Country, in Books Ireland (Dec. 2005), p.286: ‘[...] This is the Country is a novel covering the bleakness of the underbelly of Irish life. It could be an unbearably harsh read, but Wall has infused his tale with lyricism and true compassion. A bright teenager drops out to a world of drugs and violence, and hovers at the edges of gangland society in present-day Ireland. Then he makes his girlfriend pregnant. Embracing his role as lover and father, he manages to turn his life around. He becomes a marine engineer and lives a conventional life. He “even pays tax on non-cash transactions”. Then news of a murder brings back the old fears. Can he escape the violence of his past? It’s harder still, when the establishment seems set against you. / This is told in the first person by the unnamed hero. The language reflects his world, but it’s always fresh and vibrant. By the novel’s close, coherence has come in; and the words are touched with a sweet tenderness to sugar the sadness. / Wall’s novels have always had the capacity to move the reader. In this novel, the tenderness emerges more gradually; the reader will be taken by surprise when the build up of emotion becomes overwhelming. [... &c.].’

| Thomas MacCarthy, “Cork Poetry in Its Wider Context” - Cork City Council Libraries |

| [...] |

William Wall, a fine poet born in Whitegate, Co. Cork, in 1955, is now better known as a novelist and short-story writer, but his poetry is still supremely crafted and deeply felt. His Kavanagh Award winning Mathematics and Other Poems (1997) is well worth studying. Gerry Murphy, the most popular Cork poet of the modern era, published his first collection, A Small Fat Boy Walking Backwards, in 1985. He published Rio de la Plata and all that in 1993, and followed this with Extracts from the Lost Log-Book of Christopher Columbus and The Empty Quarter. His Selected Poems is published in 2006. Murphy is a terrific talent, at once playful and serious, with a keen sense of irony and a craftily-disguised sense of social justice. His ‘Oedipus in Harlem’ is pithy, pitiless and profound, but a poem like ‘After Goethe’ also captures essential elements of his method and style:

‘All nine of them -

the Muses of course -

used to visit me.

I ignored them

For the warmth of your arms.’

|

| [...] |

|

|

[ top ]

John Kenny, ‘Craving the Normal’, review of This is the Country, in The Irish Times (14 May 2005), p.13: ‘Though he still sometimes works in poetry, Corkman William Wall now tends to refer to himself as a “lapsed poet”. Comparatively quietly, yet speedily, his new reputation has been established by the three novels he has published in the last five years. A crucial factor in the respect Wall has incrementally won for his prose over this short time is the identifiable uniformities of his subjects. Even though they vary somewhat in style, Alice Falling (2000), Minding Children (2001) and The Map of Tenderness (2002) have all focused to a significant degree on the domestic social unit, something Wall once underlined in an interview with this paper: “I’m fascinated by the way families disintegrate. It can happen so easily; the bonds that hold people together are so obscure. And the idea that blood is ticker than water is rubbish.” His baneful take on the Irish family, his fundamentally anti-idyllic mood, have not enirely endeared Wall to the more misty-eyed among his readers at home or abroad. / With an echo at its very end of the rejected blood-versus-water imperative, This is The Country sustains both the core mood and theme that Wall has established as his mètier. We are in perhaps even more comprehensively sinister country this time. [...; for full text, see infra.]

Fiona Sampson, review of Water and Power, in The Irish Times (19 Feb. 2005), Weekend, p.10. ‘[...] In Fahrenheit Says Nothing To Me, William Wall [...] gives us the poet struggling to read all that’s incomprehensible in the world today. And throughout this volume reading, or paying attention, stand-in for attempted engagement with that world: “Reading in poor light / errors accumulate / I see things that have / only a tenuous presence / and closer to home / I miss the numinous” (‘Postcards from the Inferno’). / However, Wall is a poet in love with both language and the world which generates it: “On sullen summer days / light comes out of another world” (‘The Coming of Fire to Ireland’); elsewhere, damselflies are “neon”. In the end sense-making, like poem-building, requires tenacity, “the tentative pilotage of living with ourselves” (‘The Old Venetian Lighthouse on Cephalonia’). If there’s occasionally a slight foreshortening in the line of its lyric and metaphysical thought, in this substantial volume Wall [...] is nevertheless conscious of his responsibilities as poet at a time when (as he says in ‘Trayer for Riding in Front’: “The omens are not good”.)’

Todd McEwen, review of This is the Country, in The Guardian (25 June 2005): ‘Call it the stuff of ITV drama, of thrillers, but there is an unnecessary melodrama to this book. William Wall is a genuine literary talent, with a poet’s gift for apposite, wry observation, dialogue and character. To his credit he hangs his talents lightly on a nervous little plot about a man escaping drugs, losing his wife to gangsters, therefore losing his daughter to the social services, and plotting to get her back. None of this is needed, for This Is the Country is a masterful, ironic book of loss and bitter optimism, money and poverty, the impossible divide between city and country. [... The title] becomes a more and more resonant title as the book progresses: in the end Wall gives us a cleverly wrapped précis of modern Ireland, the problems inherent to its new-found wealth and leisure (and what is happening to those who can’t participate in that), old class and religious divisions. The title begins as a kind of mantra, something the city chancer fleeing into the “bogs” keeps telling himself as he adjusts to a different, frightening, self-reliant way of life, and ends up meaning “this is the state of my nation”. [... &c.]’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library > Criticism > Reviews - via index or as attached.)

George O’Brien, ‘Getting to the point of surrender’, No Paradiso, in The Irish Times (12 Aug. 2006), Weekend: ‘[...] It’s in the formal inventiveness with which this dynamic is handled that the reader will find No Paradiso most distinctive and most rewarding. In addition to the author’s alert, muscular style, his painlessly communicated appreciation of obscure learning, his vaguely didactic pleasure in accurately providing a sense of place, many of these stories are distinguished by a welcome engagement with form. The “strange geometry” of the final setting in “Surrender” is reproduced in the many variations of approach and perspective contained in No Paradiso. [... &c.].’(See full-text copy in RICORSO Library > Criticism > Reviews - via index or as attached.)

Eileen Battersby, ‘Unsettling fictions’ [review of Hearing Voices, Seeing Things], in The Irish Times (18 June 2016): ‘Living is a difficult business and an ongoing seepage of random information. Personal histories gradually take shape, some through a series of tedious small events and disappointments, others by a crisis. Not that every crisis results in a tragedy, but William Wall prefers the nagging doubts and the potential minefield created by the half-told tale. / Most of all, though, is the remorse and guilt and complex shared experiences alluded to by a random comment. / Wall, who was Man Booker-longlisted for This is the Country in 2005, knows less is more. These 20 short stories are both laconic and verbose; they hiss, mutter, wink and soar with intent. This resonant little book is in fact very large indeed.’ (See full-text copy in RICORSO Library > Criticism > Reviews - via index or as attached.)

| See also Philip Coleman [TCD], review of Ghosts Estates, in Southword, 21 (2012) - copied at Salmon Poetry online [accessed 26.10.2016]. |

Sue Leonard [catches up with William Wall], ‘I couldn’t write same book twice and I wouldn’t want to’, interview article in Irish Examiner (20 May 2017): ‘“I’m an atheist. I don’t believe in ghosts, but when I was writing The Map of Tenderness I could feel my parent’s presence hovering over the book. It was very strange. / “I had a long conversation with a friend, just recently, who told me a story which I really want to write. I asked her if she was going to use it, because you can’t go appropriating the story of another writer; not when they already have a voice.” And that is the aspect of the conundrum that Wall concentrates on in The Islands. The emotionally charged novel is narrated in the alternating first person voices of Grace and Jeannie. And Grace, a fledgling writer, isn’t at all happy with her father’s version of events. / Utterly different, the two sisters keep separate secrets, and see their lives in disparate ways. The third sister, who is not given a voice, shows us yet another side to their pseudo-idyllic lives. / “The stories are primarily focused on Grace and Jeannie, and how they cope so differently with their absent father. Grace has suffered very badly, but at the end of the day she comes to terms with it.” / Wall has captured the female voice to perfection, and has those awkward hormonal emotions of a teenage girl down to a tee. That can’t have come easily? / “While we share common humanity, there are things that are unknowable. So, at its best, it’s what a man thinks a woman’s voice will be. But Liz, my wife, is an excellent reader and editor. I rely on her to put me right where I’ve gone wrong.’ [Read online.]

See also Pittsburgh U announcement of the Drue Heinz Literature Award, 2017 - online.

[ top ]

| Bert Wright, review of Grace’s Day by William Wall, in The Sunday Times [Irish edn.] (9 Sept. 2018) [sub-heading: Island strife abounds and enthrals in this powerful family tale]. |

A long time ago I had three sisters and we lived on an island,” begins William Wall’s fifth novel, in a lyrical opening chapter that neatly adumbrates the tale to be told, and piques the reader’s interest in the most wonderful way. The speaker is Grace, the eldest of the three sisters who, it seems, never lived up to her name. A self-confessed “awkward child”, she remains so “all these years later”. Straight away, the reliability of one of two principal narrators is called into question. With its garden facing the setting sun, its apple trees and fuschia, the dry stone walls and sheep and the skinny-dipping in the crystal-clear water, the island sounds idyllic but can we take the rhapsody at face value? To complete the tableau, a romantic poet figure, Richard Wood, regularly glides in to visit in his yawl, The Iliad.

As Wood drops anchor, Wall delivers what Kate Atkinson once called one of “his metaphors to die for”. When Grace swims down the chain “hauling [herself] deeper, hand over hand until [she] could stand on the bottom” she sees her “footprints on the seabed”. It’s a striking image and if, as is often said, all artists aim to leave a footprint in the sand, Wall seems to be working on it in this brilliant opening section. There is also a hint of the narrative scepticism which permeates the entire novel. “Or perhaps that’s not how it happened” Grace muses; “what I remember and what I forget may be one and the same thing.” Thus, the story of three islands and three sisters is delicately foreshadowed with a warning that all may not be as it seems.

Dysfunctional families are staples of Irish fiction but the Newman clan yields to none in the misery stakes. Tom, the father, is a writer who chronicles his family’s rustic self-sufficiency in colour pieces for The Guardian, taking great care to spend as little time as possible roughing it en famille. His radical wife Jane is complicit, believing that “children should be told everything and treated as adults”, in that hippyish 1960s sort of way. For the children, there is freedom, fresh air, and the rhythm of the seasons but, as Grace laments, “the dynamic by which we related was frightening and selfish and destructive”. Less of a home, more “a film set of my father’s devising”, Castle Island — with all its secrets, intrigues and dramas — turns out to be a toxic setting for child-rearing.

While the children run wild, Jane and Richard Wood become lovers and life rumbles on chaotically until a terrible thing happens and the illusion of tranquillity is shattered. Climbing on the ruined watchtower, youngest daughter Em suffers a tragic accident which plunges the family into a maelstrom of grief and guilt that will poison their relationships forever. In its portrayal of a simple twist of fate with huge repercussions, acute readers may hear echoes of Ian McEwan’s Atonement. Like McEwan, Wall seems to share an ambivalent view of what, almost a century earlier, Virginia Woolf dismissively dubbed “materialist” fiction that skirts around the mysteries of the inner life. The text is littered with expressions of doubt and uncertainty that we can ever really know what goes on in other people’s minds. “Nobody knows how families work or fail,” Grace protests; “tomorrow is a spinning coin, heads or tails, nobody knows which is better.” The past is unknowable and we should never trust anyone who has a simple tale to tell.

But the Newmans’ tale is far from simple and with the narrative burden passing between sisters Grace and Jeannie, the reader must choose which of their conflicting post-Castle Island stories to believe. The road to final enlightenment proves to be a long one involving two more islands, breakdowns, marriages, divorces and deaths culminating in a dinner-party showdown which for viciousness would leave Abigail’s Party in the ha’penny place. There is one tale which Tom never gets to tell because Grace opportunistically steals the manuscript from his study, only to discover it reveals the true depth of his betrayal of family. Her whole life has been a quest for revenge and in a satisfying coda she exacts it in a manner that is apposite and best left for the reader to discover.

This is a novel about a family “on the cusp of desolation” and so pervasive and oppressive is the climate of unrelenting misery, it’s close to miraculous that the Cork novelist succeeds in crafting something as compelling as Grace’s Day. That he succeeds is testimony to his immense skill as a writer. At a time when neophytes are routinely showered with praise, it’s time to appreciate an underrated veteran at the peak of his powers.

|

| available online; accessed 09.10.2018 [here reparagraphed]. |

[ top ] Quotations

| “Ghost estate” |

|

women inherit

the ghost estate

their unborn children

play invisible games

of hide & seek

in the scaffold frames

if you lived here

you'd be home by now

they fear winter

& the missing lights

on the unmade road

& who they will get

for neighbours

if anyone comes anymore

if you lived here

you'd be home by now

the saurian cranes

& concrete mixers

the rain greying into

the hard-core

|

& the wind

in the empty windows

if you lived here

you'd be home by now

the heart is open

plan wired for alarm

but we never thought

we'd end like this

the whole country

a builder’s tip

if you lived here

you'd be home by now

it’s all over now

but to fill in the holes

nowhere to go

& out on the edge

where the boys drive

too fast for the road

that old sign says

first phase sold out |

|

| —In The Irish Times (4 Dec. 2010), Weekend Review, p.11. |

[ top ]

| Q & A with William Wall - novelist and Listowel Week Writers' Workshop Director, 2015. |

Q. Who were your literary influences growing up?

A. I’ve never known what my influences were but I know what books I loved growing up. They were the usual books that you would find in a country household in the 1960s in Ireland: RL Stevenson, Dickens, my mothers detective stories, Waltons Irish Songs and Ballads, countless westerns, but also a Collected Poems of WB Yeats and a copy of Goodbye to the Hill. The book I loved most as a young boy was Treasure Island.

Q. When did you first start writing stories and poetry?

A. I started writing poetry and stories around twelve or thirteen years of age. I became seriously ill at that time and spent a lot of time in bed. In a way I wrote stories because I could no longer do other things. I wrote poetry because I wanted to imitate the ballads and later Yeats. If I could have written a song that anyone would sing I think I would have regarded it as a real achievement. I’d still love to do that. Songs have lives that poems don ‘t.

Q. You also write children’s books. In what way is it different to writing for adults?

A. I haven’t written a children’s book for many years and then it was because I was writing for my own children. They were aimed at their interests - history, the sea, adventure. They were boys’ stories, for the most part, heavily influenced by Robert Louis Stevenson. I thought about them in a completely different way to how I think about my adult fiction, but I spent just as much effort on the language and characterisation.

Q. How do your structure your writing day?

A. I wake early - six in summer, seven in winter and start with coffee. Then I work for two hours, eat breakfast, work for three hours. I write best in the morning and I try to keep the mornings free. I sometimes return to it in the evenings, but that tends to be editing. I work on a laptop and I throw nothing out. Sometimes material discarded as unnecessary or useless finds its own usefulness in a later piece of work. Over the years, those morning hours, especially the first two, have become sacred.

Q. What projects are you currently working on?

A. I’m working on a novel, as always, and I’m superstitious of talking about it. I find talking about a book in advance often talks it away. Too many good books were published over a pint or two and never got written down. I’m also working pretty continuously now in translating Italian poetry. It started as an occasional pastime, but I’ve become more and more serious about it.

Q. You won two Listowel Writers’ Week Competitions. Did you find that helpful for your subsequent writing career?

A. Yes, I won The Single Poem and The Poetry Collection Competitions. They came at a crucial time for me because they led to my first book, Mathematics & Other Poems. Every prize acts as a kind of shot in the arm. I later launched the book at Listowel Writers’ Week. I think prizes are important, as long as the writer knows that not winning one is not a judgement on her or his work but an expression of the taste of the judges.

Q. What are your impressions of Listowel Writers’ Week?

A. I first started to go there when I was a teenager because my parents took their one week’s holidays to coincide with it. It was a tremendous experience for a boy from East Cork. I still think it is one of the best literary festivals I have ever attended.

Q. Can you give an overview of what you’ll be covering in your workshop?

A. I’m looking at starting the novel, so I’m hoping the people who attend will be at that point, or returning to that point perhaps. I’ll be looking at openings, hooks, withholding information, characterisation, language, the question of plotting in advance (should you or shouldn’t you?) and anything else that comes up. I don’t have any magic formula and where writing is concerned there are no guarantees, but I hope that the workshop will help people to see their work from a different angle and perhaps get them started, or get the start working the way they want it to.

|

| —available online at Listowel Writers Week (2105) - online; accessed 13.04.2017. |

|

[ top ]

|

‘Waiting for Grace’s Day to dawn’, in The Irish Times (Sat., 11 Aug. 2018)

|

|

[Subheading: William Wall: ‘It took me eight years to write the book - every sentence took shape slowly’.

|

|

Grace’s Day began for me (appropriately at dawn) as a single sentence: “There were three islands and they were youth, childhood and age, and I searched for my father in every one.”

I don’t know where it came from: it was there in my head when I woke on a July morning 10 years ago, insistently demanding to be noticed, like a bird tapping at the window. I wrote it down and as I wrote I became convinced that the voice was a woman’s. I don’t know why. Objectively, there is nothing in the words that determines a gender. It was just a hunch, an instinct. Maybe whatever brought the sentence to my head during the hours of sleep was part of a bigger dream. It’s often like that for me, and that initial gift of a phrase gives me a voice in which to tell the story - a magical, and rare, moment in my working day.

But the sentence also presented me with a question: which islands? Almost immediately I knew the answer. The story would unfold, for the most part, in three places - in Ireland, England and Italy, in particular places that I know and love.

It opens on Castle Island, off the coast of west Cork, a beautiful empty rock facing the majesty of the Atlantic (though I imagine it further offshore than it actually is). The house where Grace and Jeannie and their family live is, in reality, a ruin on the eastern shore. It looks onto a little pebble beach and the sound that separates it from Horse Island.

It was populated until some time after the Great Famine but all that remain now are the shells of the dwellings, the dry-stone walls, a ruined castle on the cliff above the pier - a place that plays a fatal role in the novel - and sheep. This is Grace’s habitat.

The second island is The Isle Of Wight where an aunt, who was like a second mother to me, lived and where I spent many holidays as a teenager. I grew to love the chalky coast that fell into the sea after every storm, revealing fossils for the picking. I still have a fossilised sea-urchin that I found at my feet after a swim. Jeannie, the teenager who will grow up to be a geologist, is happiest here, collecting dinosaur bones and stones.

The third and final island is Procida in the Bay of Naples, the most densely populated rural area in Europe. It’s the setting for the beautiful Massimo Troisi/Michael Bradford film Il Postino (The Postman). I fell in love with the place many years ago and have struggled to write about it ever since. It is the setting for the denouement of the novel, the polar opposite of the first island surrounded by our cold North Atlantic. The conflict of the ending is, I hope, counterpointed by the luxurious and communal life of the Mediterranean.

Isolation

Grace and Jeannie and their father are islands too - the word “isolation” has its roots in the Italian word for island (isola) - and in many ways their mother is their mainland and the mainstay of their lives until tragedy overwhelms her. The book works through themes of islands and oceans, the sea eroding the land, the solid melting, everything shifting shape, lives complicated by a single mistake.

Triads and triangles, both verbal and human, are very important to the structure of the book. The triad form has a long history in Ireland going back at least to late mediaeval manuscripts. But the immediate source in my own imagination, and probably for the forgotten dream that gave me the sentence, must be WB Yeats’ The Wanderings of Oisin, but also The Circus Animals’ Desertion, with its meditation on youth and old age, Oisín led “through three enchanted islands’ and the ‘themes of the embittered heart”.

In a way (at least in the revisions), I thought of the book as a poem about landscape and the people that move through it. I wanted it to feel luxurious, full of sounds and sights and tastes and smells. I wanted my readers to taste the salt sea and the local Italian wine, to feel the cold wind of the Irish coast and the scorching heat of Naples.

It’s possible that my music listening habits influenced the decision about the gender of the narrator. Two Irish songs obsessed me at the time - An Mhaighdean Mhara (The Mermaid) and Dónal Óg (Young Donal). I collected versions of them and made full or partial translations several times. Both of them are at least partly a woman’s narrative, Dónal Óg in particular expressing a woman’s desolation and loss. I sense that guiding voice behind much of the book, though I don’t think I could identify a particular sentence or scene directly influenced by either of the songs.

Foreign country

Grace, though, is a child of the ocean, and like the mermaid of the song she is only at home on or in water and the land is a foreign country to her. She swims a lot, and each time she swims it shifts the perspective of the book a little. She is swimming away from home, from people, swimming out beyond safety, out on the deep ocean, and from that place of profundity and danger she sees things differently, or thinks she does. By contrast, her sister Jeannie is a geologist (“Jeannie loves rocks”) and the land is her natural environment. This elemental difference determines their relationship for much of their lives.

It took me eight years to write the book - every sentence took shape slowly and was cut and re-edited until it was as intense and as shapely as I could make it - but perhaps the first problem I faced was that the story would be narrated by the two sisters, Jeannie and Grace. I experimented with multiple points of view and played various games with chronology and structure, but in the end I opted for a plain pattern of alternating chapters, each one narrated by one of the sisters. To distinguish them I resorted to simple techniques: for example, the first paragraph of each chapter mentions the other sister, so by default we can conclude who is speaking; or, for another example, Grace’s narrative is in the past tense, Jeannie’s is in the present. I hope it worked. I’ll find out from my readers to whom the book will soon belong.

But I’m certain of one thing - after long years of work and waiting, it’s time for Grace’s Day to dawn. Good luck to her. |

| The Irish Times (Sat., 11 Aug. 2018) - online; accessed 11.08.2018. |

|

|

See also ‘Idyllic Childhood in East Cork”, Interview with Cork Echo (04.04.2019)

|

[ top ]

Notes

Drue Heinz Award 2017 (Pittsburgh Univ. Press): William Wall of Cork City, Ireland, won the Virginia Faulkner Award for Excellence in Writing of $1,000 for his novel excerpt in Prairie Schooner’s Winter issue. David Gates, a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 1992, selected Mr. Walls’ manuscript “The Islands”; from more than 300 submissions. “The Islands” is evocative, moving yet tough-minded, written with marvelous style and authority,” Mr. Gates said in a release. ‘After just the first few sentences, we trust absolutely that this writer is in control and knows what he’s doing. The narratives move expeditiously, even when they’re thick with description, and the characters’ voices are distinct and convincing. It was a pleasure to read.. “The Islands,” which features a series of related short stories centered on the lives of two sisters, details a family spiraling out of control. Through three stages of the girls’ lives, Mr. Wall traces their stories on three islands - one in southwest Ireland, one in southern England and one in the Bay of Naples. The University of Pittsburgh Press will publish “The Islands” later this year. The literary award also includes a $15,000 cash prize. ‘I’ve never been to the U.S.A. and I can’t think of a better way to make my first trip,’ Mr. Wall said in a release. ‘I’m hoping it brings my writing to a wider audience.’ (See Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 26 Jan. 2017 - online; accessed 29.01.2017.)

Kith & Kin: William Wall’s wife Liz Kirwan is a mathematician and author of the portrait-photo of him; a son is living in Oxford in 1017.

[ top ]

|