|

Frank Ormsby

Life

| 1947- ; b. Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh; ed. St. Michael’s College, Enniskillen, and QUB (MA, English, 1971); appt. teacher of English and then Head of English at Royal Belfast Academical Institute, 1971- ; succeeded James Simmons as editor of Honest Ulsterman acting as assistant to Michael Foley, 1969-72, then solo 1972-84, and finally with Robert Johnstone to 1989; participated in meetings of the Belfast Group organized by Seamus Heaney and Michael Allen; issued Ripe for Company ( 1971); Business as Usual (1973); winner of Eric Gregory Poetry prize, 1974; issued Being Walked by a Dog (1979); A Store of Candles (1977), Poetry Society Choice; second prize in National Poetry Comp., 1979; his collections and A Northern Spring (1886) and The Ghost Train (Gallery) were published by Gallery Press; |

| |

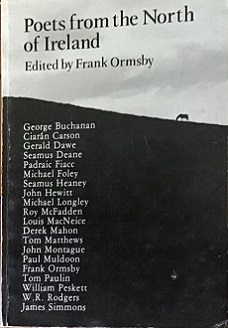

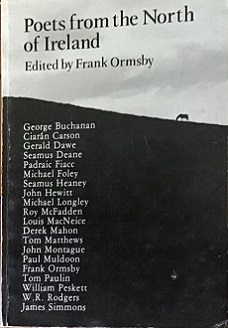

| he has edited a number of anthologies incl. the ground-breaking Poets of the North of Ireland (1979) and Northern Windows (1987), extracts from Ulster autobiography; also Rage for Order (1992), on the poetry of the Troubles - named after the title-phrase in a poem by Derek Mahon; received Cultural Traditions Award in memory of John Hewitt, 1992; also edited the Collected Poems of John Hewitt, and a selection of Amanda McKittrick Ros (1988); winner of the O’Shaughnessy Poetry Award of Univ. of St Thomas, Minnesota, 2002 ($5,000); later collections are Fireflies (2009), Goat’s Milk: New and Selected Poems (2015); The Darkness of Snow (2017), and The Rain Barrell (2019); Ormsby was elected Poetry Professor of Ireland in Aug. 2019. DIL FDA HAM ORM OCIL |

| |

|

|

Frank Ormsby (Boston Archive) and Poets from the North of Ireland (1979) [click to enlarge] |

[ top ] Works

| Poetry collections |

- Knowing My Place (Belfast: Honest Ulsterman Publications 1971), 15pp. [sole COPAC copy in Oxford U Libraries].

- Ripe for Company (Belfast: Honest Ulsterman Publications 1971), [2], 18pp.

- Spirit of Dawn (Belfast: Honest Ulsterman Publications 1973), q.pp.

- Business as Usual (Belfast: Honest Ulsterman Publications 1973), 16pp. [QUB; BLibrary].

- Being Walked by a Dog (Belfast: Honest Ulsterman Publications 1979).

- A Store of Candles (OUP 1977; rep. Gallery Press 1986), xxvii, 140pp.

- A Northern Spring (Oldcastle: Gallery Press/London: Secker & Warburg 1986), 56pp.; [Q. another edn. (London: David & Charles 1986), 53pp. [listed Ergodebooks, Richmond, Texas];

- The Ghost Train (Loughcrew: Gallery Press 1995), 53pp.

- Fireflies (Manchester: Carcanet 2009), 60pp. [Oxford Poets edn. 2011, 300pp.]

- Goat’s Milk: New and Selected Poems, intro. by Michael Longley (Tyne & Ware: Bloodaxe Books 2015), 257pp.

- The Darkness of Snow (Hexham: Bloodaxe Books 2017), 128pp.; another edn. (Winston-Salem, NC : Wake Forest University Press, [2017]), 160pp..

- The Rain Barrell (Hexham: Bloodaxe Books 2019), 104pp.

|

| Anthologies |

- ed., Poets of the North of Ireland (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1979), 320pp. [contains poems by George Buchanan, Ciaran Carson, Gerald Dawe, Seamus Deane, Padraic Fiacc, Michael Foley, Seamus Heaney, John Hewitt, Michael Longley, Roy McFadden, Louis MacNeice, Derek Mahon, Tom Matthews, John Montague, Paul Muldoon, Frank Ormsby, Tom Paulin, William Peskett, W. R. Rodgers & James Simmons.]; also new edn., full rev. & updated (Belfast: Blackstaff 1990), xiv, 336pp.

- ed., The Long Embrace: Twentieth Century Irish Love Poems (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1987; rep. 1990), xiv, 190pp. [in mem. John Hewitt].

- ed., Northern Windows, an Anthology of Ulster Autobiography (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1987), 256pp.

- ed., Thine in Storm and Calm: An Amanda McKittrick Ros Reader (Belfast: Blackstaff 1988).

- ed., Collected Poems of John Hewitt (Belfast: Blackstaff 1992).

- ed., Rage for Order (Belfast: Blackstaff 1992).

- ed. The Hip Flask: Short Poems from Ireland (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 2000), xx, 147pp., ill. [, woodcuts by Barbara Childs].

- ed., The Blackbird’s Nest: An Anthology of Poetry from Queen’s University, Belfast (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 2006), q.pp.

- ed., with Michael Longley, John Hewitt: Selected Poems (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 2007), xvii, 140pp.

- ed., with Fleontia Flynn, The Yellow Nib (QUB 2015), 87pp.

|

| Prose |

- Ulster Poetry and the Troubles [Poetry and the Conflict in Northern Ireland: A Troubles Archive Essay] (QUB [q.d.]), 28pp. [boxed set of 12 pamphlets by Ormsby et al.].

|

| See also |

- Floods / Words (Belfast: Arts Council 1972), col. poster 76x51cm.

- A recital from The Blackbird’s Nest: An Anthology of Poems from Queens University, Belfast (2006), is available at Blackstaff Press - online [1.11.2011].

|

[ top ]

Criticism

Patricia Horton, “An Appetite for Poetry”, interview with Ormsby, Causeway (Autumn 1995), pp.51-56; Ronald Marken, ‘“A Line’s Trail in the Water’: The Poetry of Frank Ormsby’, in Irish University Review, 14 (Autumn 1984), pp.221-27; Ron Marken, ‘Michael Foley, Robert Johnstone and Frank Ormsby: Three Ulster Poets in the Go Situation’, in Poetry in Contemporary Irish Literature, ed. Michael Kenneally [Studies in Contemporary Irish Literature 2; Irish Literary Studies 43] (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1995), pp.130-43.

| Adrienne Levey, interview with Frank Omsby, in The Irish Times (6 Aug. 2019). |

How did you first get involved in writing poetry?When I was 10 or 11, a teacher set us writing poems for a competition at Enniskillen Show. I won a second prize with a poem about a dog or a dogfight. The challenge of constructing quatrains and finding rhymes and solving the problem of getting the syllable count right in each line must have triggered something in me. Pattern and music. I went on to write imitations of the patriotic verse in a magazine called Ireland’s Own and by the time I had entered St Michael’s College, Enniskillen, I was already filling small notebooks with verse. Very little of this early stuff has survived.

How important was Seamus Heaney to you in your development as a poet?

When I came to Queen’s as an undergraduate in 1966, the year of Death of a Naturalist and Heaney’s first year as a lecturer in the English department, I came across his poems (and those of Michael Longley, Derek Mahon and James Simmons) in Harry Chambers’ magazine Phoenix.

When Simmons published my first poem in The Honest Ulsterman (February 1969), he described it accurately as “pastiche of Heaney”. After it appeared, Heaney took me aside and invited me to join the writers’ group which at that time met in the English department. On the same day, Heaney introduced me to Michael Foley on the steps of the Students’ Union. Simmons had asked Foley to take over the editing of The Honest Ulsterman. Foley was willing to do so provided he had someone to help. I was that helper. I am recording this by way of illustrating Heaney’s dynamic presence at this time and his significance to me in all sorts of things.

In addition, of course, his poetry opened up the subject matter of rural Ireland, reinforcing and extending the work of Kavanagh and Montague. He was a towering figure in Irish poetry for decades. The number of critical studies of his work and the appearance of his books on university syllabuses all over the world attest to his popularity and influence.

Aside from Heaney, I would imagine that John Hewitt is also an important influence on your work. You edited The Collected Poems of John Hewitt, a book which Wes Davis praises as “the standard edition of that fundamental poet of cultural alienation in the North”. Can you speak a little about what Hewitt’s work means to you?

I was not an admirer of Hewitt from the start. When he privately published a pamphlet of poems called An Ulster reckoning in 1971, he quoted, in the foreword, John Montague’s description of his as “the first (and the last) deliberately Ulster Protestant Poet. That designation carries a heavy obligation these days.” Hewitt sent a review copy to The Honest Ulsterman with a note to the effect that he expected the usual dismissive mention. My review in The Honest Ulsterman No 29, July/August 1971 comments: “Unfortunately it is not difficult to give second rate poetry a spurious importance by playing this sort of game - let’s call it the Dilemma of the Ulster Protestant Poet or Look! I’ve got a spilt identity”. Hewitt has played this game for a long time” - there were two pages of this. It was brutal then and it is brutal now.

Hewitt wrote to me from Coventry, where he was curator of the Herbert Art Gallery. The letter was dignified and angry and he struck a satirical note, advising me to develop a more effective “hatchet-man” style by imitating models such as William Hazlitt. Detecting an element of hurt in the letter, I wrote an apology to Hewitt, which was accepted. Shortly after this, he retired from the Herbert Gallery and returned to Belfast. Michael Longley introduced me to him at the Festival Club on February 9th, 1972 after I had taken part in a reading with Michael Foley, Paul Muldoon and William Peskett at the Students’ Union. Back in Belfast, Hewitt became a father figure to several generations of poets and won honours galore. He quarried new collections from his notebooks, revising poems from as far back as the Forties. After our initial skirmish, we settled down and developed a friendship. I found him gruff and kindly, always ready to give judicious praise.

It is difficult to say (I think) whether Hewitt influenced my poems - unless it be in the use of traditional forms, a fondness for short poems and, occasionally, a four-square quality. Hewitt certainly detected a poetic affinity. My diaries for the 1970s tell me that when the Arts Council commissioned a set of poster poems, Hewitt was particularly enthusiastic about my collaboration with the artist John Middleton - “I like your poem very much and have it hung in the porch where I can see it daily”. During a visit I made to his house in Stockman’s Lane in October 1973, he told me that my poetry appealed to him more than that of any Ulster poet “currently writing”. Hewitt was not given to overstatement. I admired his nature poems and lyric poems generally. When Michael Longley and I edited Hewitt’s Selected Poems (2001), I think both of us were surprised by the rediscovery of a considerable lyric poet.

How do you decide on a poem’s form? At what point in composing do you decide on shape?

Poems often suggest themselves, as it were, in an opening line in the poet’s head and the line often has a particular rhythm which is then likely to become the rhythm of the poem. So, by the end of the first verse, I am likely to have a sense of whether the poem will be in free verse, blank verse, couplets, quatrains, or whatever. If the poem itself suggests form and shape, it is usually “better” than a poem in which the poet imposes a form.

A connection to place is very important in your poetry, and your rural upbringing in Fermanagh features in much of your work, beginning with your first collection, A Store of Candles (1977). This preoccupation with the local seems more prevalent in the work of Northern Irish poets than in the work of Southern poets (with the exception of Patrick Kavanagh). I’m thinking specifically about poets such as Louis MacNeice, John Montague and Seamus Heaney. Would you agree with this assessment or am I making too broad an assumption?

The local is a starting point for the Southern poet as much as it for the Northerner. I notice this when I read newspaper and magazine contributions by young Southerners and register the local fidelities. The Troubles, however, have given Northern poets a sharper sense of place. This is likely to persist as the bodies of the Disappeared continue to be raised from bogland and other landscapes. The landscape is not, as Hewitt remarks, “to be read as pastoral again”.

Your second volume, A Northern Spring (1986), includes a section of 36 poems about the American GIs who were stationed in Fermanagh ahead of the Normandy landings in 1944. Your close friend Michael Longley also writes often on war, though in his case his poems center on his father’s experience in the first World War. What prompted you to aesthetically explore this chapter in Northern Ireland’s history, and to what extent did the backdrop of the Troubles influence the creation of these poems?

We lived on the periphery of the Necarne Castle or Castle Irvine estate, near the village of Irvinestown, Co Fermanagh. During World War II there had been an American hospital camp in the woods and when I was a boy there were still a couple of air-raid shelters (see The Air Raid Shelter in a A Store of Candles). I was born in 1947 and had no direct memories of the American presence, but the GIs related particularly well to the nationalist community and there were numerous stories about them.

A Northern Spring is an attempt to imagine their lives and experiences. I have given them voices in the style of Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology. The sequence is about the fate of the universal soldier who has his future taken from him. The Troubles are to the fore in some of these poems, a significant undercurrent in others. The use of dramatic monologue is intended to strengthen our sense of the soldiers as individuals at a time when soldiers and policemen in the North of Ireland were being dehumanised as “legitimate targets”.

I saw “Apples, Normandy, 1944” as a poem about the pressure of expectation on artists to produce “relevant” work about the Troubles and the obligation of the artists to maintain their independence and follow the dictates of their art. Soldier Bathing moves from Lough Melvin in Co Fermanagh to Lucifer’s War in heaven and the “Let there be light” moment. The title is borrowed from a well-known WWII poem by FT Prince. The images that run through Maimed Civilians, Isigny would be very familiar to anyone who had heard about or seen photographs of various atrocities in the North and the stunning capacity for recovery shown by the casualties.

In your poem “The Heart” from your third collection, The Ghost Train (1995), you describe Belfast as a city that “aspires to be the capital of bereavement”. Your recent poetry celebrates the city’s rejuvenation. How difficult was it to write poetry about the Troubles?

It was easy enough, indeed all too easy to write about the Troubles. It was more difficult to allow the material to find its “imaginative depth” (as Michael Longley put it) and write the poems with a weight appropriate to the seriousness of the subject. My anthology A Rage for Order: Poetry of the Northern Troubles did not appear until 1992, almost 25 years after the Troubles began, by which time poets had absorbed the subject - not entirely, of course, but sufficiently to approach the topic thoughtfully and with authority.

Your father’s stroke and early death cast a long shadow over your poetry. In Goat’s Milk: New and Selected Poems (2015), the poems about his death are particularly moving. Do you find the experience of writing about your father to be cathartic?

Cathartic, yes. He presides over the poems and even answering this question brings a familiar image of him. White hair, cap, walking stick. He is almost always seated and silent but somehow manages to remain an authority figure. We will take a short walk, during which he will keep one hand on my shoulder. My mother will give him an insulin injection and I will feed him porridge with a spoon.

You were also an English teacher and later head of the English Department at one of Belfast’s leading schools, The Royal Belfast Academical Institution. I believe you taught there from 1971 until your retirement in 2010. Can you speak a little about your career as an educator?

Royal Belfast Academical Institution (also known as RBAI... and Inst) is a Boy’s grammar school located in the centre of Belfast. It is essentially a Protestant school but prides itself on being open to pupils of all denominations. It makes a point of not enquiring into the religious background of staff or pupils. My professional life as a teacher was spent there. I was an assistant teacher of English from 1971 to 1976 and head master of the English fepartment from 1976 to 2010. The school was founded to be the local university, which explains the head master. i inherited humanities, as it were, and was also head of history and geography, though in name only.

The school might be described as a boys’ scientific and mathematical academy but it did have a literary tradition. Sir Samuel Ferguson was a pupil there, as was William Drennan, the United Irishman. The Edwardian novelist Forrest Reid was another pupil, more recently the poets Michael Longley and Derek Mahon. The poets Robert Johnstone and William Peskett were educated at Inst. John Hewitt was a pupil there for one year, circa 1919. I realise that this answer has become a survey but I want to mention three other interesting figures - the painter Paul Henry, Dr William Neilson, head master of the classical school, who taught Irish and, in 1808, published an Irish Grammar, and the poet Charles Reavy, poet, translator and founder of the Olympia Press.

I loved teaching literature every working day but probably had more impact simply as a poet on the staff. A poet who managed a school hockey team! I’m speculating that this normalised poets and poetry in some way.

There were opportunities to introduce classes to contemporary Irish writers - Flann O’Brien was a great hit. I taught the poetry of Yeats, MacNeice, Kavanagh, Heaney, Longley, Mahon, Muldoon and Carson and, occasionally, my own poems. By the way, Adrienne, do you know what the Tollund Man’s full name is? Pete Brown. And that the opening line of Heaney’s Mid-Term Break is “I sat all morning in the college sick bay” and that “ambition was Macbeth’s athlete’s foot”?

Your current collection, The Darkness of Snow, contains 14 poems about your experience with Parkinson’s. I’m wondering if you are familiar with Susan Sontag’s book, Illness as Metaphor, in which she argues that the clearest way of thinking about disease is without recourse to metaphor. Many writers disagree with her thesis, arguing that metaphor and other types of symbolic language help afflicted people form meaning out of their experiences. What are your thoughts on this?

I haven’t read Susan Sontag’s book yet, so I don’t feel in a position to comment on it. I have had a sense of metaphor in action. When I walk into a room, there is a second in the course of which I see coats, cushions, clocks, etc. as people but they resume, almost immediately, their own shapes. I can only assume that what happens is caused by medication.

You have become much more prolific in your writing since being diagnosed with Parkinson’s. Would you attribute this new burst of creativity to the fact that you are now retired and have more time to devote to writing or are there other factors also at play?

Retirement has played a significant part. It used to take me nine years to get a book together, now it takes two. I think medication plays some part in this. Just as it can make your mind wander, it can also encourage feats of concentration that can be useful when you are trying to finish a recalcitrant poem. Furthermore, I am a man in a hurry. I have diabetes type 2 and Parkinson’s and have had the experience of being taken suddenly into hospital and I know that the diseases are potentially fatal. From that point on, I am in a hurry. I feel free but psychologically I must have a sense, however deeply buried poetry is in there, that my time is limited and that I must get the poems on to paper whatever. All this is speculation and even perhaps a little ridiculous.

You were the editor of The Honest Ulsterman from 1969 to 1989. How did the poet and editor in you work together in shaping the magazine? Also, were you surprised how influential the magazine became?

There was no tension between the poet and the editor! I think I had a kind of throwaway editing style and was lucky to be able to call on an enviable group of contributors. I would visit The Eglantine Inn on the way home from RBAI. Paul Muldoon would be there after a day at the BBC, Ciaran and Deirdre Carson and John Morrow would arrive from the Arts Council and others might appear - painters, teachers, musicians, individuals such as Ted Hickey, Keeper of Art at the Ulster Museum, and Conor Macauley, my colleague at RBAI. The poets often brought new stuff and I often left with a few pages filled in the next issue of the magazine. There was a personal element in all this that kept the potential drudgery of editing at bay. I dealt with the printers and booksellers and my first wife Molly helped with parcelling and mailings.

Add the names of terrific poetry critics such as Edna Longley and Michael Allen and the provocative, splenetic, opinionated columnist, Jude the Obscure. Add the contribution of the non-Irish poets such as Gavin Ewart and Carol Rumens. Editing The Honest Ulsterman was, for me, one of the excitements of the literary life in Belfast from, roughly, 1968 to 1988.

Was I surprised at how influential the magazine became? It is difficult for me to answer this because I had very little sense of the nature of the influence. The magazine helped to keep poetry and therefore the peacetime values of poetry alive for almost the entire duration of the Troubles. It published the earliest writing of a formidable group of writers, such as Paul Muldoon, Ciaran Carson, Michael Foley, John Morrow, Bernard MacLaverty, Tom Paulin, Peter McDonald, Medbh McGuckian. The pamphlet press, Ulsterman Publications, published the work of Heaney, Longley, Mahon and Simmons, as well as Muldoon, Carson and company, establishing a poetic continuity.

Yes, I suppose these activities and achievements constitute influence and that I shouldn’t be surprised at this. I was surprised at the magazine’s capacity to recover its freshness after periods in the doldrums but this statement may be as much about me as it is about the magazine!

During a previous conversation you told me that after The Darkness of Snow was published Dr Kath MacDonald, a senior lecturer in the nursing division at Queen Margaret University in Edinburgh, contacted you to ask permission to use your Parkinson’s poems as teaching aids in the nursing program. It’s rare for poetry to achieve such a practical impact outside the artistic sphere. Are you aware how the poems have been received by the nursing students?

After I gave a reading in the Scottish Poetry Library in Edinburgh, Dr Kath MacDonald asked for permission to use the Parkinson’s poems as teaching aids in the nursing program. This approach was marvelously unexpected and led to a couple of workshops with the pupils studying neurological diseases and the staff who taught them. The emphasis was on the need to develop empathy skills, so literature fitted in. The students studied a number of appropriate poems and wrote haiku poems embodying forms of empathy.

|

| Available online; accessed 06.09.2019. |

[ top ]

Commentary

Fred Johnston, review of The Ghost Train and collections by other poets, Irish Times (27 Feb. 1996), Weekend Review, p.9, noting an echoing, however lightly, of Robert Graves; poems incl. “The Last Word” [‘Between what is and what is not / We walked, the Huntress loosed a shot ... yet we, transparent, without fear / What were we but singing air?’; also “A charm on the Night of Your Birthday”; “You Made your Hair a Sail to Carry Me’. Also “Of Certain Architects, Technicians, and Butchers”; “Trial by Existence”; judged a varied but decently crafted work.

Oonagh Warke, review of The Ghost Train, in Books Ireland (May [q.d.]), p.130; carriages of memories; cites titles, “Geography”, “The all Ireland Campaign”, Roslee hero”, “One Saturday”, Gatecrasher”, “Reading to My Father”, “The Charlotte Gibson Bed”.

[ top ]

Quotations

| “Blackbirds, North Circular Road” |

| |

Were here long before us,

so seem to preside

through our first winter.

Snow in the garden

a chance not to be missed,

they swivel and flit,

as though in time and space

they mapped the neighbourhood:

a random, elliptical print

their work in progress.

This one a Presbyterian,

sleeping rough

in the grounds of Rosemary Church.

The one disposed

to match profiles with Cavehill:

a tunic rag from an old rebellion.

Settling and re-settling,

a third recalls the merchant Jew who built here.

We share his view

of distant shipyard cranes,

the glint of water.

And this must be the Blackbird of Belfast Lough,

released to the air one summer

from the verge

of a monkish gospel.

Yes, this will be Yellow Bill

on the latest leg of his journey, fluttering down

yards from the study window, bringing us the free

gift of his ease in the barbed winter hedges,

nonchalant,deft slalom in the snowbound tree.’

|

| |

| —The Irish Times (8 March 2002) |

| “For the Record” |

When I stabbed a Belfast gigolo at the Plaza

they transferred me to the country to cool down.

There were no poolrooms or waterfront hotels,

just woods, cows, a village, flat fields

and enough fresh air to poison a city boy.

And when the MPs kicked me senseless in Duffy’s Bar

for being a “wise guy”, I burned their quarters down

one night in May with gas from their own jeeps

and they could prove nothing.

Cornered at St-Marcouf, I shot my way

to a medal and commendation (posthumous),

a credit at last to my parents, whoever they were,

and the first hero produced by the State Pen.

|

| |

| —Quoted on Facebook by Eunice Yeates [18.06.2014] |

[ top

References

James Simmons, Ten Irish Poets (Cheadle: Carcanet 1974), selects “Business as Usual”; “Interim”; “Winter Offerings”; “In Great Victoria Street”; Floods”; “Dublin Honeymoon”; “Hair Horseworm”; “Three Domestic Poems”; “Onan”; “McQuade”; “Castlecoole”; “An Uncle Remembered”; “Virgins’.

Peter Fallon & Seán Golden, eds., Soft Day: A Miscellany of Contemporary Irish Writing (Notre Dame/Wolfhound 1980), “Interim”; “A Small Town in Ireland”; “A Country Cottage, Towards Dawn’.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3 selects from A Store of Cold Candles, “Island”; “A Northern Spring”, “Mcconnell’s Birthday”, “Home” [1400-1401]; BIOG, p.1435.

Patrick Crotty, ed., Modern Irish Poetry: An Anthology (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1995), selects “Passing the Crematorium” [306]; “Home” [306]; from “A Paris Honeymoon: L’Orangerie” [307].

[ top ]

Notes

Belfast Group: Materials held amongst his papers in Emory Library (Collections) include worksheets by Norman Dugdale, Seamus Heaney, Michael Longley, Paul Muldoon, Bernard MacLaverty, and James Simmons from meetings of the Belfast Group in 1971-1972.

x

|