|

Hanna Sheehy Skeffingon

Life

| 1877-1946 [ Mrs. Sheehy Skeffington; - freq. Sheehy-Skeffington]; b. 28 May, Kanturk, Co. Cork; eldest of six children (two sons) of David Sheehy, mill-owner and [m. Bessie [née McCoy]; raised initially at The Mill, Loughmore, Co. Tipperary; family settled in Hollybank, Drumcondra, Dublin, on his election to Westminster as a Nat. MP for Meath in 1887 [and later for Galway]; moved to lived at 2 Belvedere Place, where James Joyce [q.v.] visited frequently - and where scenes in his draft-novel Stephen Hero are set; 6 siblings of whom Mary [m. Thomas Kettle, q.v.] and Kathleen [m. Frank Cruise O’Brien and afterwards mother of later mother of Conor Cruise O’Brien, q.v.]; ed. in Loughmore and Eccles St. Dominican Convent School, Dublin; briefly sent to sanitorium in Germany in teen-age; entered St. Mary’s University College, London; sat Royal University Examinatinos, BA, 1899; spent some time as an au pair in Paris; grad. by exam. for MA [1st Class], RUI 1902; |

| |

| m. Francis Skeffington [q.v.], 3 June 1903, at the University Chapel [Church], Dublin; worked as teacher at Dominican Convent and Intermediate Examiner; with her husband, Margaret Cousins and James Cousins fnd. Irish Women’s Franchise League, with aim of getting women’s voting rights included in Third Home Rule Bill, 1908; launched Irish Citizen; imprisoned for breaking windows in at Dublin Castle opposition to John Redmond at the exclusion of women’s suffrage from the Bill, 1912; imprisoned in Mountjoy with eight others for her part in a protest at the GPO that involved breaking windows, June 1910 (including Majorie Hasler, who died in 1913); threw a hatchet Asquith, PM, during his visit to Dublin; dismissed from her teacher post; imprisoned and when on hunger strike; released and rearrested; |

| |

| she was close to James Connolly and Constance Markievicz and carried messages in the 1916 Rising; refused compensation for murder of her husband Francis, murdered by the British officer Bowen-Colthurst - who then harrassed the widow at her home during subsequent raiding parties; contrib. to Irish Citizen and United Irishman; extended lecture tour in America, Dec. 1916-1918; supported Sinn Féin [raising $120K] and served as asst. ed. of An Phoblacht; issued “British Militarism as I Have Known It” (NY 1917), a pamphlet - jointly with a reprint of her husband’s “A Forgotten Small Nationality” [Century Magazine, 1916]; met President Wilson, Jan. 1918; arrested and imprisoned with Maud Gonne and others, 1918; hunger-strike lead to her release; |

| |

| served on Executive Committee of Sinn Fein; she served as judge in pre-Independence Dáil courts; supported the Republican side in the Civil War as a member of Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League; played active part in fomenting the Plough and the Stars riot in the Abbey Theatre, Dublin (Feb. 1926); revisited America, and later visited Russia, 1929; arrested in Newry and imprisoned for one month in Northern Ireland for defying exclusion order, Jan. 1933 [var. 1931]; fnd. Women’s Social and Progressive League; died April 1946, at Easter - near the anniversary of her husband’s murder; her “British Militarism [... &c.]” was then reprinted in The Kerryman (Tralee); bur. with her husband in Glasnevin; the Gender Studies Building in UCD (Belfield campus) is named after her; there is a memorial statue in Kanturk and a plaque at the scene of the government windows she smashed in the GPO [var. Dublin Castle]; her grand-dg. Michelline teaches at UGG [NUI Galway]. DIH |

|

|

|

|

|

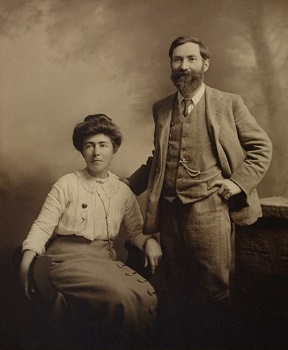

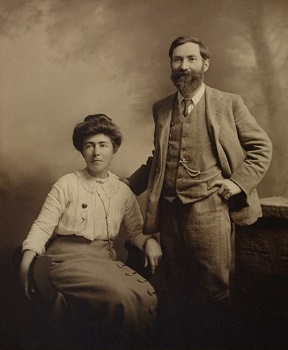

Hanna and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington

|

|

Hanna in 1916 |

Commemorative Statue, Kanturk |

[ top ]

Works

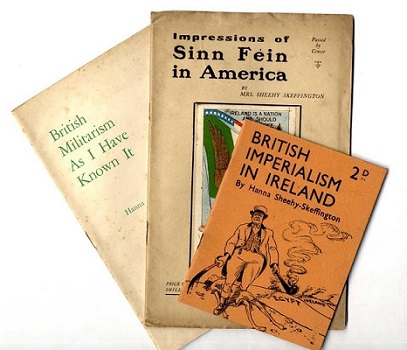

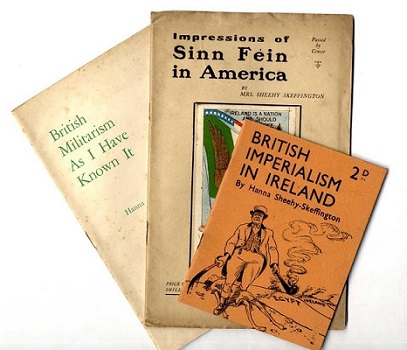

British Militarism as I Have Known It [digest of a lecture] (NY 1917) [jointly with A Forgotten Small Nationality, by Francis Sheehy Skeffington, as pp.17-32; available at Internet Archive - online; see copy attached]; Do. [rep. edn.] (Tralee: The Kerryman 1946), 22pp.; ‘The Women’s Movement - Ireland’, in The Irish Review (July 1912); ‘Reminiscences of an Irish Suffragette’, in Votes for Women: Irish Women’s Struggle for the Vote, ed. A. D. Sheehy-Skeffington & R. C. Owens ([priv.] Dublin 1975).

| Her journalism includes - |

- ‘Sinn Fein and Irishwomen', in Bean na hEireann, 20, 13 (Nov. 1909), pp.5-6.

- ‘Why We Throw Stones at Government Glass Houses’, in Irish Citizen (22 June 1912), p.17.

- ‘Jail, a University’, in Irish Citizen (10 Aug. 1912), p.95.

- ‘The Duty of Suffragists’, in Irish Citizen (15 Aug. 1914) [q.p.].

- ‘The Women’s Movement - Ireland’, in Irish Review, 2, 17 (July 1912), pp.225-27.

- ‘Constance Markievicz and What She Stood for’, in An Phoblacht (16 July 1932), pp.7-8.

|

| —All cited in Karen Margaret Steele, Women, Press, and Politics During the Irish Revival (Syracuse UP 2007), Notes [see extract]. |

|

|

Pamphlet Publications

of Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington

|

[ top ]

Criticism

- Leah Levenson & Jerry H. Natterstad, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffinton: Irish Feminist (Syracuse UP 1986).

- Maria Luddy, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington [Historical Association of Ireland; Life and Times ser., No. 5: ] (Dundalk: Dundalgan Press 1995), 63pp.

- Margaret Ward, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington: Suffragist and Sinn Féiner (Dublin: Attic Press 1996), 329pp. [pb. 1997].

- Margaret Ward, ‘Nationalism, Pacificism, Internationalism: Louie Bennett, Hanna-Sheehy Skeffington and the Problems of “Defining Feminism”’, in Gender and Sexuality in Modern Ireland, ed. Anthony Bradley & Maryann Gialanella Valiulis (Massachusetts UP 1997) [q.pp.].

- Margaret Ward, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington: A Life (Cork UP/Attic 1997), 392pp.

- Bryan Fanning, ‘ James Connolly and Catholic nationalism’, in Histories of the Irish Future (London: Bloomsbury 2015), pp.151-68 [Chap. 10; partially available at Google Books - online].

|

| Women’s Studies. |

- Ethel Mannin, Women and the Revolution (London: Secker & Warburg 1938), and Privileged Spectator (London: Jarrolds 1939).

- C. L. Innes, ‘“A Voice in Directing the Affairs of Ireland”, L’Irlande libre, The Shan Van Vocht, and Bean na h-Eireann’, in Paul Hyland & Neil Sammells, eds., Irish Writing, Subversion and Exile (London: Macmillan 1991), pp.146-58. [on her contribution to Bean na h-Eireann]

- Margaret Ward, ‘“The Suffrage Above All Else!”: An Account of the Irish Suffrage Movement”, in Irish Women’s Studies: A Reader, ed. Ailbhe Smyth (Dublin: Attic Press 1993).

- Conor Cruise O’Brien, ‘My Time at Trinity College’, in The Recorder: Journal of the Irish American Historical Society, 13, 1 (Spring 2000), pp.7-37 [see extract], and O’Brien, Ancestral Voices, Religion and Nationalism in Ireland (Dublin: Poolbeg 1994) [ chiefly in connection with her espousal of the role of Republican widow after 1916 and her active part in the Plough and the Stars riot].

- Joanne Mooney-Eichacker, Irish Republican Women in America: Lecture Tours 1916-1925 (Dublin: IAP 2003), xxii, 329pp.

- Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, the most resistant writer of the lot [Alice Milligan, Anna Johnston, and Maud Gonne] distanced herself from the capitulating pressures of nationalist discourse about feminity by refusing to draw on the ethos of motherhood in militant suffrage debates. (p.16.)

|

| See also — |

- Lis Phil, ‘Fragments of Feminism in Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and Signe Toksvig’, in Fund og Forskning, Bind 40 (2001) - online; accessed 29.05.2014 [incls. photos of Hanna Skeffington, et al.

- Karen Margaret Steele, Women, Press, and Politics During the Irish Revival (Syracuse UP 2007), 275pp. see extract].

|

| Note: Lis Pihl (b.1930) died on 22 Feb. 2010. |

[ top ]

Commentary

Sean O’Casey, Inishfallen, Fare Thee Well (London: Macmillan 1949) [Chap., ‘Temple Entered’], giving account of public debate with Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, who he describes thus: ‘A very clever and a very upright woman … turned the dispute into an academic question because … she wished him to do the same.’ (pp.188; and see under Notes, infra.)

| Notice on the Sheehys in Loughmore, Co. Tipperary - from Hidden Tipperary - online [10.11.2022]: |

| |

[..] About 1878 David Sheehy (Hanna Sheehy’s father), his wife Bessie (née McCoy), and their eldest child Hanna, came to live; renting the Mill in Loughmore. David was born in County Limerick and attended the Irish College, studying for the priesthood, in Paris with his older brother, Eugene, [n.1] latter known as the ‘Land League Priest‘ and also one of Éamon de Valera’s teachers. However he (David), was sent home from Paris during an outbreak of cholera, there in 1866. On his return home he became implicated in the ill-fated Rising of 1867, after which he fled the country going to sea. After a few years he returned home and ran a mill at Kilmallock and later at Kanturk, before renting the mill at Loughmore around 1878. It was while in Kanturk that he married Bessie McCoy, [n.2] who was from the region of Ballyhahill, in Co. Limerick.

David and Bessie went on to have seven children, six of whom were born in the village of Loughmore, Thurles, Co Tipperary. Before the end of the century the whole family had moved to No 2. Belvedere Place, Dublin. David became Secretary to the Irish Parliamentary Party and an M.P. for Meath and later for South Galway; a post he held until the Sinn Féin landslide of 1913. James Joyce, a student at the nearby Belvedere College was a regular visitor to No 2. Belvedere Place, in 1896-1897 and he nursed a secret love for Hanna’s sister Mary, who was later married to Irish economist, journalist, barrister, writer, poet, soldier and Home Rule politician Tom Michael Kettle. Bessie died in 1917 and David around 1932/33, at the age of 86.

Before moving to Loughmore, his eldest daughter Hanna Sheehy had been born 3 years earlier in Kanturk, North Co. Cork, on the 24th May 1877.

Notes:

1. In 1886 Fr Eugene Sheehy was C.C. of Kilmallock, Co. Limerick and later P.P. of Bruff. He resigned in 1909 because he had gotten into trouble with his bishop, Dr Edward Thomas O’Dwyer. He went to live with the Sheehy’s who were then living in Dublin. He was jailed in Kilmainham with Charles Stewart Parnell. He died in 1917 and is buried in Glasnevin cemetery.

2. Bessie’s sister Kate was Mrs Kate Barry of Barry’s Hotel, Dublin.

|

| |

|

| |

Gives extract of "Reminiscences of her childhood in Loughmore" from a newspaper of 1938: |

| |

It lay nearly half-way between Templemore and Thurles in Co. Tipperary, with the Devil’s Bit for a background. I made its acquaintance at the age of three, and lived there in the old Mill till I was ten. I can wish nothing better for any child than to be born and brought up in the country - you miss a lot your whole life long if you have not had such a start.

The railway line from Kingsbridge to the South lay midway between the Mill and the Village, and right at the top of the latter were clustered church, graveyard and school. One of my earliest recollections is listening to the Rooks, cawing from the high tree tops in the graveyard from the open door of the national school as we conned our “tasks” in the big room, our one schoolroom for the girls and younger boys, with a class at each corner and one often in the middle as well. Outside in that same graveyard stands the monument to the Cormack brothers, wrongfully hanged in penal times, whose name was cleared and bodies buried there later.

The Mill was pure romance - the mill race fed from the Suir, the house and kitchen garden, outhouses and grove at the back being practically on an island. Our outer gate closed at night like a fortress shutting us in. The bakehouse was across the yard - the smell of new-made bread is another childhood memory, and the sight of the huge batches shoved into the gaping oven: if you were good, the baker let you knead some dough for a little loaf of your own. And the sound of the doves cooing around the corn and all the wonders of the loft, the granary, the revolving wheel, the sound of running water - water all around, so that we were sometimes caught by flood and marooned - all these made a wonderful childhood setting, and what playgrounds did they offer! Years later, when I revisited the place, I was amazed to find how everything seemed to have shrunk to much smaller dimensions. To childhood’s eyes distances are vast.

Outside the gate we swung an arch (how laboriously made, how elaborately festooned, ivy and boughs of flowering shrubs, slung on a rope) to welcome Archbishop Croke, come for Visitation, to the parish - the first after his return from Rome with his immortal “Unchanged and unchangeable” [See note]. On one side we painted on canvas the phrase (we did not grasp its full meaning then, we just knew it was “a famous victory”) aided by the mill-boys. On the other side we put the word “Wealcome” - it is to the credit of our elders that they left as it was written, for the whole was a spontaneous offering, spelling and all! and the Archbishop’s keen grey-blue eyes twinkled as he passed and caught sight of it.”

“For we had a highly political atmosphere, a beloved uncle being in jail, first in Naas, then in Kilmainham, during part of that time, one of the “Suspects” - did he not send us sweets from each place? We played at evictions and had to conscript Emergency-men from the boys of the village (naturally everybody wanted to be evicted tenants) while we fortified our holdings in the hen-house and hay barn, yelling Fanny Parnell’s “Hold the Harvest”! We hummed derisively “The Peeler and the Goat” as the sleek sergeant passed the gate in the evening, and when a grabber seized a holding in the parish, we took our part in the boycott with the vim of youth for any fray.

Literary memories of a staider kind were the reading aloud at the family circle of Knocknagow, and the equally thrilling (not so public) perusal of Jane Eyre, high in the branches of a cherry-tree across the stream. Grandmother told us stories of the Famine as bed-time yarns, or of O’Connell, whom she knew in her youth - the grandparents revered him, but we sided with our parents, who, loving the Fenians, had no use for Dan. Purcell’s Castle was hard by, with its ruins of other days and its fearsome dungeons that we loved to explore.

In school I learned “the rudiments of Arithmetic”, the chief towns of Ireland (both have stayed with me) and not much else. Oh, yes, a number of most complicated games that we played in the lunch interval in the school yard - I can now only remember one called “Hell and Heaven” like “Oranges and Lemons.” And, of course, “Tig” and “Rounders”. The rest of our education was outside the school. We knew where the first primrose and violet could be gathered, and where the richer land for cowslip and and mushroom lay; we made balls of the former, and mother made ketchup such as one may never taste now. The early lambs, the speckled trout in the stream, the blackbird’s nest in the wall cranny by the lilac-tree, left undisturbed of course; the larks in the far meadow; the fairies in the fort; the Seanachie at Gleeson’s or Dea’s or Hennessy’s, where the young people gathered with the old, around the big fire and watched the old grandmother spin while the tales were told - of highway men, of men on their keeping, of cruel landlords, and how vengeance surely, slowly tracked them down, of ghosts and headless horsemen, of Banshees ... I hope our folk-lore archives have got some of them.

The mill-wheel turns no more, but the ‘Suir’ flows by majestically as of yore, and the Devil’s Bit looks down benignly on old Loughmore.” [End.]

|

| |

Note: Archbishop Thomas Croke had been summoned to Rome by Pope Leo XIII and Cardinal Simeoni. He had been recalled to answer questions regarding his continued support of Charles Stewart Parnell. Following his meeting and prior to his return he stayed at the Irish College in Rome and when questioned regarding the outcome of his meeting with both men, Archbishop Croke had stated that he returned to Ireland “Unchanged and unchangeable.”

|

| |

The site includes information about the Sheehy siblings and relations and cites James Joyce as "nursing a secret love" for Mary Sheehy. It also recounts the execution of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington under orders by Capt. Colthurst-Bowen by firing-squad in Portobello Barracks [sic]. The accompanying video includes an interview with Monk Gibbon who speaks of return on his own authority to the cell in which Sheehy-Skeffington was held and speaking with him minutes before his execution. See the YouTube at Hidden Tipperary online or directly at YouTube - online. |

|

[ top ]

Conor Cruise O’Brien, ‘My Time at Trinity College’, in The Recorder: Journal of the Irish American Historical Society, 13, 1 (Spring 2000), pp.7-37. O’Brien gives a full account of her personality and several episodes in which her republican nationalism was manifested; also tells of of tongue-lashing that he received from Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington as a child and another years later when he and Christine Foster accidentally set fire to a curtain, causing him to experience a ‘regression’ so that he could not answer back, and attributes the break-down of his marriage to Foster to this event. He further remarks, ‘Years later, when I readof Hanna’s shattering impacton Seán O’Casey in the debate over The Plough and the Stars, I know exactly how O’Casey felt. I had been unnerved, at a critical moment in my life, just as he had been unnerved.’ (p.36.)

Bernard Adams, Denis Johnston: A Life (Dublin: Lilliput Press 2002) [on The Treaty with the Barbarians, a provocatively-titled play by Gordon Campbell]: ‘The occasion was attended by the high priestesses of Irish nationalism, Maud Gonne, who brought along supporters - including Hanna Sheehy Skeffington - ready to create trouble if the temple were defiled. However, the play proved disappointingly unpolitical and no opportunities for protest presented themselves.’

Karen Margaret Steele, Women, Press, and Politics During the Irish Revival (Syracuse UP 2007): ‘Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, the most resistant writer of the lot [Alice Milligan, Anna Johnston, and Maud Gonne] distanced herself from the capitulating pressures of nationalist discourse about feminity by refusing to draw on the ethos of motherhood in militant suffrage debates.’ (p.16; available at Google Books - online.)

[ top ]

Quotations

Disillusion? ‘What a time we live in! Here we are rapidly becoming a Catholic statelet under Rome’s grip - censorship and the like. […] I have no belief in de Valera. Well-meaning, of course, better than Cosgrave, but really essentially conservative and church-bound, anti-feminist.’ (Quoted in Margaret Ward, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, 1997; in Louise Ryan, review, Irish Studies Review, Aug. 1998, p.197.)

Emancipation [on ‘the disabilities of Irish women suffer today’:] ‘The result of Anglicisation? This is partly true; much of the evil is, however, inherent in latter-day Irish life. Nore will the evil disappear, as we are assured, when Ireland comes [in]to her own again, whenever that may be. For until the women of Ireland are free, the men will not achieve emancipation.’ (Margaret Ward, In Their Own Voice: Women and Irish Nationalism, Attic Press 1995, q.p.; quoted in Marie Duffy, UU Diss., UUC 2007.)

British myth: According to her foreword to the 4th edition, British Militarism As I Have Known It ‘disposes forever of the myth (widely circulated by British writers and military apologists) that the murder of Sheehy Skeffington was the isolated act of a demented British officer’. (See Abebooks - online; accessed 01.01.2015).

[ top ]

Notes

Sean O’Casey: The Plough and the Stars riot was fomented by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington on the first [var. fourth] night, followed by a public debate with her in which O’Casey fumbled for his notes – events causing him to leave Ireland for London, 1926. On that occasion she accused him of insulting ‘the Ireland that remembers with tear dimmed eyes all that Easter week stands for’, to which he replied that ‘some of the men cannot even get a job’, and that Mrs Skeffington [‘]appears to be blind and deaf to all the things which are happening around her’ (1926; q. source.)

IWFL: [Francis] Skeffington founded the Irish Women’s Franchise League with Margaret Cousins in 1908 - a group that ‘from its inception harried the Irish Home Rule Bill.’ (See Margaret MacCurtain, ‘Women, the Vote and Revolution’, in Women and Irish Society, the Historical Dimension, ed. MacCurtain & Donncha Ó Corrain, Dublin 1978; quoted in Cheryl Herr, For the Land they Loved, 1991, p.60.)

|

| Plaque in at GPO (Dublin) [var. Dublin Castle] |

Citizens Inc.: John Mitchel founded The Citizen in New York in 1854; a newspaper written for the Irish community was published in Sydney (Australia, NSW) as The Irish Citizen from 2 Dec. 1871 to 31 Aug. 1872 (2 vols.; 1+14 issues) [see online]. A Dublin-based newspaper similarly called The Irish Citizen was established by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington [q.v.] with Margaret Cousins [q..v.] - sometimes cited a James Cousins, her similarly feminist husband - and continued to appear during 1912-20. The entire series is available at the Irish Newspaper Archives - online [a pay site]. A bound copy of the second volume (issues of 24 May 1913-16 May 1914) was presented to the TCD Library by A[ndrée] D. Skeffington in memory of her father [Prof.] Owen Sheehy-Skeffington, son of Francis and Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, in Feb. 1977 [TCD Cat. IN-20-98]. The banner of that paper, printed and sold in monthly issues bears the motto, “For Men and Women Equally, / The Rights of Citizenship / For Men and Women Equally / The Responsibilities of Citizenship. The contents have been digitised and are available at TCD Library - online; accessed 04.06.2024. (See also under John Mitchel - supra.)

| “On Offensive Cartoon”: In our St. Patrick’s Day Number we published a cartoon depicting Mr. Redmond as the Angel of Freedom, proclaiming liberty for Irish men, with his foot on Irish womanhood bound and prostrate. The cartoon was seen by all the Dublin Press; but its caustic meaning escaped them until, to months later, the London correspondent of both the Freeman and the Telegraph discovered that it was ‘offensive.’ With delightful naivete both papers set out in words the subject of the cartoon - for all the world to see and realise the truth. The oily "Freeman" suppressed the name of this paper for fear of advertising us; but its evening brother made up for it by reproducing the cartoon, thus making itself an accessory to the offence and adding t the boom of the Citizen. We quite agree that the cartoon is offensive. It shows up one of the most glaring political offences of all time; and we remember the profound words of Holy Writ: ‘Woe to him by whom offence cometh.’ |

| —Available at TCD Library - online; accessed 05.06.2024. |

[ top ]

|