“The Dead Travel Fast”: Deadly Transports

A quizzicality about the role of Bürger’s “Lenore” in Dracula

by Bruce Stewart

Some weeks ago I taught Bram Stoker and Irish Gothic to a small group of students at UFRN in North-East Brazil. As apart from the lively confirmation of the universal popularity of that novel, and its curious character as a piece of second-rate writing (ha!) which goes to the heart of the modern neurosis on various fronts - sexual, alimentary, colonial, and so on - the class threw up a new interest in the actual language of the novel and especially its system of allusions .. among which the line expressly quoted from Gustave August Burger’s 1773 ballad “Lenore” is the most striking: “Denn die todten rieden schnell” - which Stoker immediately translates in a parenthesis as “the the dead travel fast”. In this he has substituted “travel” for the usual translation-terms “ride, gallop” and so on. In seeking where he got his translation - assuming that he did not merely think it up - I first explored the translation-history of the original into English and came up with such writers as William Whewell and Dante Gabriel Rossetti both of whose versions are routine reproduced on websites dedicated to Stoker’s Dracula and all of its materials and themes. Yet neither of these include the word “travel” and the only indication of an alternative source was - enchantingly, it must be said - Charles Dickens’ famous “A Christmas Carol” in which Scrooge asks of Marley’s ghost, “You travel fast?” (The dialogue is cited on the Wikipedia page for Bürger’s “Lenore”.) Could it be that Stoker was echoing Dickens in a story that he must have known and which, indeed, might well have been staged in a production he had seen? Stoker was a theatrical manager and knew a great deal of the contemporary drama scene, especially the popular diet since he was, after all, the manager of a popular theatre with the opposite of a fastidious taste for high-class literature - as Flann O’Brien facetiously calls the more intellectually demanding kind. It was then that I loaded up my trivial researches on Facebook with a query about the proximate source of Stoker’s word “travel”. And then came back the results ... .. in the form of Neil Mann’s treasure-house of information about the exploitation of Bürger’s line in various European contexts - notably its rendering in French as “les mort vont vite” by Madame de Stael - a version that went, well, viral at the time. And then, Eureka! Neil throws in a reference to The Corsican Brothers of Dion Boucicault staged in 1852 - itself based on a novel by Dumas about Siamese twins - in which Farbbyang says, “The dead travel fast”. So, then, Boucicault - an Anglo-Irishman from Dublin and an older contemporary of Stoker who topped the British and American bill with his rumbuctious melodramas was the first to translate Burger’s “rieden” as “travel”. Or so it seems. Yet Dickens’s “Christmas Carol” (1843) had already celebrated its tenth birthday when Boucicault pasted together his show and it is unlikely that he had not met the Scrooge-Marley dialogue, just as Stoker may have known it independently of the Corsican debâcle. On further searching, it turns out that Neil’s independent research is amply warranted by Catherine Wynne’s condensed account of the Boucicault-Stoker connection which also identifies the Punch review he mentiones - in which the one about the line of mortal transport is cited as the only good one in the play. (Wynne doesn’t find it necessary to make the connection with Burger’s ballad as cited in the text of Dracula, however.) So where does that leave us? It is certainly possible to construct a fashionable interpretation in which the colonial remainder - as some philosopher has called it - is shown infusing a constant amount of “Irish-Gothic” into the blood-streams of Boucicault and Stoker, with similar arrangements made for Le Fanu and Maturin and anyone else who falls within the shock-waves of postcolonial criticism. In such a view, Dracula appears to be first and foremost a product of the Anglo-Irish literary tradition considered as an insular (and insulated) literary growth. There is much to dispute this, not least the fact that Stoker was a middle-class Irish protestant and not a demon-landlord of any kind. More tellingly, however, if his source for the Burger translation - as I will call it for short - is Dickens rather than Boucicault, or both together, he is just another British chap writing horror stories for the Victorian stage in London, Dublin, Philadelphia or wherever an audience for that sort of thing can be found. It is true that the death travel quick but not as quick, it seems, as a good literary line - and that has been the case with Gustav August Burger’s ‘denn der todten rieden schnell which seemed, for much of two centuries, to be as unkillable as Dracula himself. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first chapter of Dracula contains a quotation from the macabre and once-popular ballad “Lenore” published by Gottfried August Bürger in 1773 - one among many other literary references to Shakespeare, Byron, Walter Scott and sundry scientific writers, named and unnamed, which imbue that horror-story with a surprisingly literary character. (For some sense of the range of allusions in the novel, it is worth visiting the extraordinary Bookmarks page compiled by Victoria Hooper on Bookdrum - online.) The passage in question describes Dracula’s first appearance in the novel as an anonymous - and ominous - presence. This is how it goes:

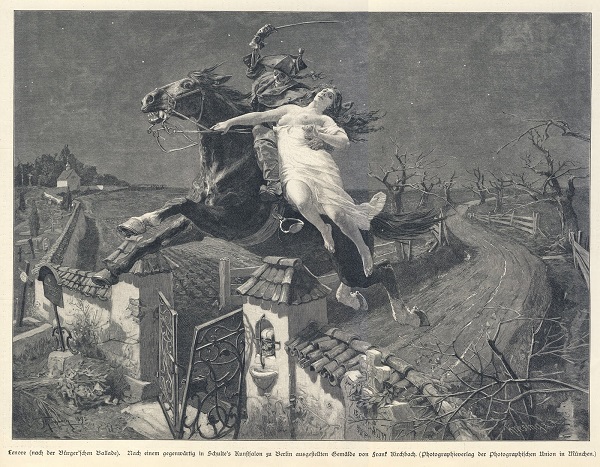

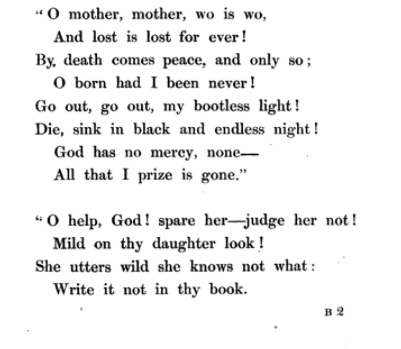

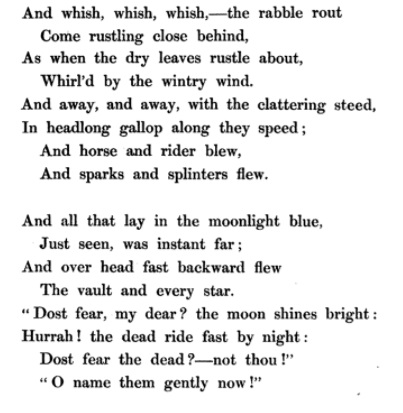

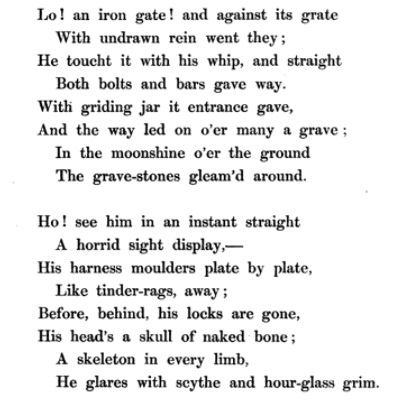

It appears that the passenger who quotes Bürger here is harping on the narrative of the famous ballad in which a young woman pining for her lost beloved, a soldier who went off to war and has not returned, is visited by a horseman in his likeness who promises to take her to their bridal bed but who is actually Death who takes her on a whirlwind ride across intervening lands and seas to the graveyard where his bones lie and invites her to join them in the grave. (She dies but her soul ascends to heaven because she begs forgiveness the sin of despair in God’s redemptive power.) It is speech near the end of the poem where the horseman sheds the similitude of William and reveals his true character as Death which the passenger quotes - meaning to suggest that the faceless coachman in the calèche - as distinct from the driver of their own work-a-day post-chase - has the aspect of the Grim Reaper:

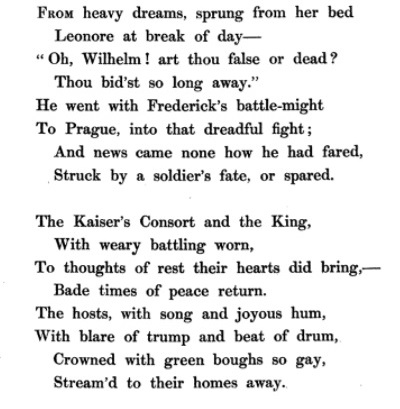

The effect is very much that of a ghost-story - or a vampire tale - in which a deathly figures leads his victims out of the world. It is also reminiscent of the carriage-ride with which Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla begins. Nor would thoughts about Emily Dickinson’s poem on Death as a coachman be entirely out of place. In fact Bürger’s poem was written in response to Johann Gottfried Herder’s call for a national German literature reflecting the vernacular potential which he detected in Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765) and the MacPherson’s Ossian poems (The Works of Ossian, 1765) and, indeed, Burger made it clear that his ballad was equally based on a German folk-tale and on the Scottish ballad “Sweet William’s Ghost” which Percy had printed in his collection. All of this was part of the rising tide of European Romanticism but also the new interest in spooky stories as the stuff of polite literature. Stoker clearly knows the German ballad in the original since he quotes it in that language, yet English translations had been going the rounds since William Taylor published his to great acclaim in the Monthly Review in March 1796 (though written and circulated in manuscript six years earlier). Taylor’s version might seem a likely candidate for the epithet ‘travel’ in the translated line from Bürger’s ballad - but alas, no. That translation is reprinted in The Broadway Anthology of Romantic Poetry (2016) and contains the following lines: ‘Tramp, tramp, across the land they speede; / Splash, splash, across the sea; / “Hurrah! the dead can ride apace; Dost fear to ride with mee?”’ (ll.189-93; see online.) Sadly the Google Books version of the anthology breaks off here, but the point is adequately made that Taylor is a rider rather than a traveller - a notion for which Charles Dickens may have supplied the surprising source, as I note below. Other translators who left into the rign in 1796 were J. T. Stanley and H. J. Pye and W. R. Spencer, while Walter Scott made a version with a different title - “William and Helen” which is nevertheless pure translation. We know that he heard the poem being read in an Edinburgh drawing-room and was sufficiently impressed to seek out the manuscript in Germany and to translate it in one day in 1794. Yet another translation was made by a very precocious Dante Gabriel Rossetti at the age of 16, in 1844, of which these are the relevant lines:

It is worth glancing here at Sir Walter Scott’s treatment of the speedy travel motif in his quatrains:

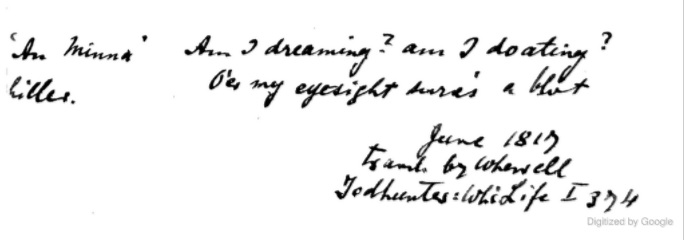

In these he is reproducing the Death’s repeated refrain in the original as he approaches the would-be ‘bridal bed’. The version I have quoted first above is the one made by William Whewell in circa 1817 and published anonymously in a pamphlet publication of 1829, and afterwards in Verse Translations from the German including Bürger’s “Lenore” [and] Arthur Schiller’s “Song of the Bell” and Other Poems (1847) - a copy of which is available at Bookdrum [online]. (Regarding the identity of the author of that book and its date of composition, see infra.) Clearly none of these - Whewell, Scott or Rossetti - are the source of the succinct translation which Stoker places in parenthesis after the German original that serves to convey the (presumably German-speaking) passenger’s intuition about the ghastly identity of the mysterious aristocratic coachman. What stands perhaps out in Stoker’s rendering is the word ‘travel’ for Reiten [lit. ‘ride’] and this does not appear to come from any previous English version. Similarly his rendering of schnell as ‘fast’ has an appreciable blunt force. Who the editor is who adds that translation to the text, it recks not to ask - but certainly not Jonathan Harker in whose journal it appears. That Bürger’s poem and English translations of it influenced the English Romantics is well established; Charles Lamb, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth all mention William Taylor’s version in their letters to each other after its appearance in the Monthly Magazine in May 1796 [see note]. Wordsworth even held that version to be superior to the German, though Coleridge characteristically did not agree. The several complex transactions surrounding those translation were brilliantly appraised by Oliver Farrar Emerson in English Translations of Burger’s Lenore - A Study in English and German Romanticism (Cleveland, Ohio: Western Reserve UP 1915), the chief source of my information on the subject [available at Internet Archive - online]. A similar deposition has been made by Marti Lee who claims that that ‘Lenore had a tremendous influence on the literature of the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-centuries, and in fact, today’s popular horror books and movies are still feeling the reverberations.’ He goes on:

This seems to apply well to Stoker’s Dracula in which the novelist not alone echoes the theme of the deadly abduction but also incorporates an explicit allusion to Burger with an utterly apposite quotatioin thrown away in conversational mode by the entirely admirable wit of German extraction on the inside of the Transylvanian public carriage. It oddity is that Stoker not only borrows the line but also mentions the author - much as he mentions Max Nordau and Cesare Lombroso in the course of Van Helsing’s diagnosis of Count Dracula’s ontological problems in terms of the criminal type and the recidivist tendencies of his ‘child brain’. It is an odd habit on Stoker’s part and one that reveals him as something of an intellectual show-off and, of course, a determined practicioner of the Irish art of fiction which, as in the case of his compatriot James Joyce, is guaranteed to keep the professors busy for centuries. Stoker’s fascination with the line from Bürger - no throwaway reference, therefore - is demonstrated by its recurrent in “Dracula’s Guest”, a later short-story in the form of a narrative told by Jonathan Harker who writes: ‘On top of the tomb, seemingly driven through the solid marble - for the structure was composed of a few vast blocks of stone - was a great iron spike or stake. On going to the back I saw, graven in great Russian letters: “The Dead Travel Fast”’. In this rendering, the English version of the phrase which is offered as a parenthetical translation in Dracula features as the original even to the extent that the little story omits to say whether the “Russian letters” are used to transcribe the English or the Russian version - or perhaps, more logically, the German original which Stoker has omitted to mention on this occasion, as he also fails to mention the poet who first wrote the phrase that reverberates so noisily in his vampire writings. According to one website, source, in later life Bürger was dismissed by Franz Schiller who had the monopoly of literary fame in German, and died alone and ignored on 8 June 1797, and ‘and would probably now be completely forgotten if it were not for Bram Stoker.’ (‘“Denn die Todten reiten schnell” - Its Meaning and Origin’, at Hubpages, 14 Dec. 2013 - online; accessed 02.10.2017.) On that website the original couplet is given as, ‘Sieh hin, sieh her! der Mond-scheint hell. / Wir und die Todten reiten schnell.’ - with a variant quotation from Rossetti’s translation from the one I have given above. Thus:

These are actually earlier lines in the poem - ll.132-32 - as consultation with the Rossetti Archive at Harvard will show - while the lines that correspond to Burger’s original phrase occur repeatedly at ll.157-59, 189-91, as show [above]. (It is rather oddly the case that Rossetti’s translation is most often quoted in illustration of Burger’s original on English-language websites - as for instance the Dracula page of Infocult: Uncanny Informatics [online; accessed 02.10.2017.] Finally, as the Wikipedia article on “Lenore” reminds us, the following dialogue occurs between Scrooge and Marley in “A Christmas Carol”: ‘“You travel fast?” said Scrooge. “On the wings of the wind,” replied the Ghost.’ It would seem, then, that the penultimate verse from Bürger’s “Leonore” is like a klaxen note to be heard in numerous English romantic tales - a notice of the presence of death-in-life and life-in-death which is the very stuff of the supernatural tale and which, indeed, even extends into the liminal conclusion of Joyce’s great short story “The Dead”, though with the help of Bürger’s phrase. It may in fact be that Dickens is the immediate source for the translation-term ‘travel’ for reiten in the original since we have not been able to find it in any other translation. If so, Jacob Marley and Count Dracula have formed an unlikely joint-stock company in the world of English literature - or perhaps not so unlikely after all! BS 02.02.2017 |

||||||||||

[ top ]

Appendix 1: “Lenore” by G. A. Bürger, translated by William Whewell

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[ top ]

|

|

|

|

|

| Who wrote Verse Translations from the German: including Bürger’s Lenore [...] (1847)? |

|

—Isaac Todhunter, William Whewell, Master of Trinity College, Cambridge: An Account of his Writings (Cambridge UP 1876; digital version 2011) - online |

[ top ]

| Facebook friends remind me of a number of other-language texts which either reference or resemble Burger’s ballad. Firstly, there is Goethe’s Erlkonig [Erl King] which Brian Ings cites in full: | ||

Es ist der Vater mit seinem Kind; Er hat den Knaben wohl in dem Arm, Er faßt ihn sicher, er hält ihn warm. “Mein Sohn, was birgst du so bang dein Gesicht?” - “Siehst, Vater, du den Erlkönig nicht? Den Erlenkönig mit Kron und Schweif?” - “Mein Sohn, es ist ein Nebelstreif." “Du liebes Kind, komm, geh mit mir! Gar schöne Spiele spiel’ ich mit dir; Manch’ bunte Blumen sind an dem Strand, Meine Mutter hat manch gülden Gewand.” - |

Was Erlenkönig mir leise verspricht?" - "Sei ruhig, bleibe ruhig, mein Kind; In dürren Blättern säuselt der Wind.” - “Willst, feiner Knabe, du mit mir gehn? Meine Töchter sollen dich warten schön; Meine Töchter führen den nächtlichen Reihn, Und wiegen und tanzen und singen dich ein.” - “Mein Vater, mein Vater, und siehst du nicht dort Erlkönigs Töchter am düstern Ort?” - “Mein Sohn, mein Sohn, ich seh’ es genau: Es scheinen die alten Weiden so grau. -” |

Und bist du nicht willig, so brauch’ ich Gewalt.” - “Mein Vater, mein Vater, jetzt faßt er mich an! Erlkönig hat mir ein Leids getan!“ - Dem Vater grauset’s, er reitet geschwind, Er hält in Armen das ächzende Kind, Erreicht den Hof mit Müh’ und Not; In seinen Armen das Kind war tot. |

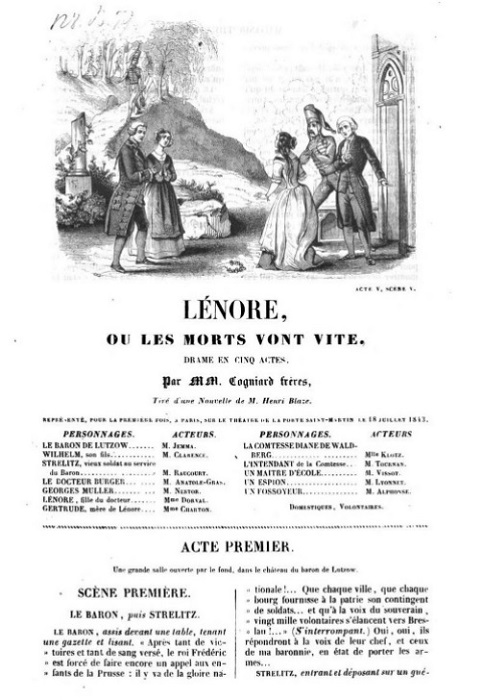

Neil Mann reports that Kenneth Koch was fond of citing Bürger’s famous line in his own poetry - but in French. He writes: ‘Madame de Stael mentions it in De l’Allemagne, translating as “Les morts vont vites, les morts vont vite”.’ He further writes that the ballad was translated into French by Gérard de Nerval in five different versions as well as by Stendhal and Hugo, remarking that the form of translation established by Madame de Stael predominates in all of their efforts (‘the alliteration no doubt helps.’) According to Neil it was also turned into a play by the Cogniard brothers as Lénore; ou, les morts vont vite (1843) a piece which Stoker might have known. Also mentioned here are a painting of 1825-30 by Ary Scheffer entitled Les morts vont vite (in Lille and Paris) and another by Horace Vernet (Nantes) of an 1839 called La ballade de Lénore ou les Morts vont vite while Alexandre Dumas (fils) wrote a novel on the theme as Les morts vont vite (1861). |

||

[...]

[...]

|

|

|

|

||

[ top ]

|

|||

Let the bell toll! - a saintly soul floats on the Stygian river - And, Guy De Vere, hast thou no tear? - weep now or never more! See! on yon drear and rigid bier low lies thy love, Lenore! Come! let the burial rite be read -the funeral song be sung! - An anthem for the queenliest dead that ever died so young - A dirge for her, the doubly dead in that she died so young. “Wretches! ye loved her for her wealth and hated her for her pride, And when she fell in feeble health, ye blessed her -that she died! How shall the ritual, then, be read? -the requiem how be sung By you -by yours, the evil eye, -by yours, the slanderous tongue That did to death the innocence that died, and died so young?” Peccavimus; but rave not thus! and let a Sabbath song |

The sweet Lenore hath “gone before,”with Hope, that flew beside, Leaving thee wild for the dear child that should have been thy bride - For her, the fair and debonnaire, that now so lowly lies, The life upon her yellow hair but not within her eyes - The life still there, upon her hair -the death upon her eyes. Avaunt! tonight my heart is light. No dirge will I upraise, But waft the angel on her flight with a paean of old days! Let no bell toll! -lest her sweet soul, amid its hallowed mirth, Should catch the note, as it doth float up from the damned Earth. To friends above, from fiends below, the indignant ghost is riven - From Hell unto a high estate far up within the Heaven - From grief and groan to a golden throne beside the King of Heaven." |

||

Online Literature > Edgar Allen Poe - online; accessed 03.10.2017. |

|||

|

|||

Henry James, The Golden Bowl (1904); filmed by James Ivory (2000), with Kate Beckinsale & Nick Nolte |

|||

[ top ]

| The following bibliography is given in the notes to Wikipedia article on “Lenore”: |

|

See Wikipedia online. |

[ top ]

Appendix 5: The Boucicault Connection

| Neil Mann writes [in reply to BS]: |

|

—posted on Facebook, 04.10.2017; given here with minor edits. |

[ top ]

Appendix 6: Bram Stoker and Victorian Gothic Theatre

Catherline Wynne has given a substantial account of Stoker’s indebtedness to Boucicault’s Corsican Brothers in her recent book Bram Stoker, Dracula and the Victorian Gothic Stage (2013): |

|

This neatly indicates that the textual inclination of our enquiry is wholly consistent with the tendency in recent theatrical research and that our guess is right: Stoker took the translation-term “travel” from his older contemporary the Anglo-Irish playwright Dion Boucicault - though, of course, the German original which he cites is entirely due to his own familiarity with, and memory of, the famous ballad. (It’s appropriately German provenance is also an issue here.) Catherline Wynne - herself Irish and a teacher at Hull University - has edited the theatrical reviews of Stoker in the Dublin Daily Mail (Bram Stoker and the Stage (Pickering & Chatto 2012) and has also given the opening lecture in the week-long Stoker Centenary series of “The Essay” (BBC3), commencing 16 April 2012. It is worth reading her remarks on Stoker’s immersion in contemporary stage-Gothic at at greater extent: |

|

|

Note: Traill is the novelist H. D. Traill, a friend of Stoker’s. |

|

—Catherine Wynne, Bram Stoker, Dracula and the Victorian Gothic Stage (London: Palgrave Macmillan 2013), [38-40; end of Chap. 2]; available at Google Books - online; accessed 04.10.2017]; |

[ top ]

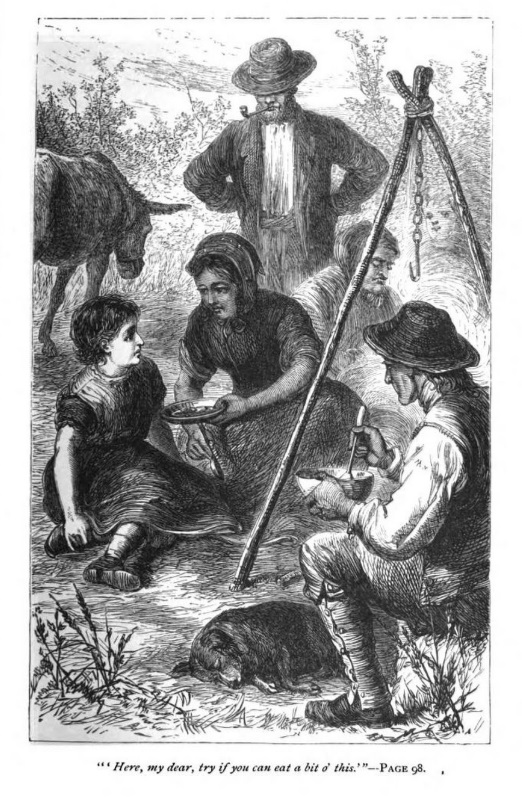

George Eliot refers to Leonora

|

|

(p.100); available on internet at Google Books - online. |

| [ back ] | [Index ] |

[ top ] |